Taiwan under Japanese rule

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2021) |

Taiwan | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1895–1945 | |||||||||||

Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||

Anthem:

| |||||||||||

Seal of the Governor-General of Taiwan | |||||||||||

Taiwan (dark red) within the Empire of Japan (light red) at its furthest extent | |||||||||||

| Status | Colony of the Empire of Japan | ||||||||||

| Capital and largest city | |||||||||||

| Official languages | Japanese | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Taiwanese Mandarin Chinese Hakka Formosan languages | ||||||||||

| Religion | State Shinto Buddhism | ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) |

| ||||||||||

| Government | Government-General | ||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||

• 1895–1912 | Meiji | ||||||||||

• 1912–1926 | Taishō | ||||||||||

• 1926–1945 | Shōwa | ||||||||||

| Governor-General | |||||||||||

• 1895–1896 (first) | Kabayama Sukenori | ||||||||||

• 1944–1945 (last) | Rikichi Andō | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Empire of Japan | ||||||||||

• Treaty of Shimonoseki | 17 April 1895 | ||||||||||

• Surrender of Japan | 15 August 1945 | ||||||||||

| 25 October 1945 | |||||||||||

• Treaty of San Francisco | 28 April 1952 | ||||||||||

• Treaty of Taipei | 5 August 1952 | ||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 1945 | 36,023 km2 (13,909 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Currency | Taiwanese yen | ||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | TW | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Republic of China (Taiwan) | ||||||||||

| Japanese Taiwan | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 日治臺灣 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 日治台湾 | ||

| |||

| Japanese name | |||

| Hiragana | だいにっぽんていこくたいわん | ||

| Katakana | ダイニッポンテイコクタイワン | ||

| Kyūjitai | 大日本帝國臺灣 | ||

| Shinjitai | 大日本帝国台湾 | ||

| |||

| History of Taiwan | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Chronological | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Topical | ||||||||||||||

| Local | ||||||||||||||

| Lists | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

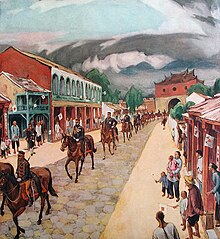

In 1895, all the islands of Taiwan, together with the Penghu Islands became a dependency of Japan when the Qing dynasty ceded Taiwan Province in the Treaty of Shimonoseki after the Japanese victory in the First Sino-Japanese War. The short-lived Republic of Formosa resistance movement was suppressed by Japanese troops and quickly defeated in the Capitulation of Tainan, ending organized resistance to Japanese occupation and inaugurating five decades of Taiwan under Japanese rule. Its administrative capital was in Taihoku (Taipei) led by the Governor-General of Taiwan.

Taiwan was Japan's first colony and can be viewed as the first step in implementing their "Southern Expansion Doctrine" of the late 19th century. Japanese intentions were to turn Taiwan into a showpiece "model colony" with much effort made to improve the island's economy, public works, industry, cultural Japanization, and to support the necessities of Japanese military aggression in the Asia-Pacific.[1]

Japanese administrative rule of Taiwan ended after the end of hostilities with Japan in August 1945 during the World War II period, and the territory was placed under the control of the Republic of China (ROC) with the issuing of General Order No. 1.[2] Japan formally renounced its sovereignty over Taiwan in the Treaty of San Francisco effective April 28, 1952. The experience of Japanese rule, ROC rule, and the February 28 massacre of 1947 continue to affect issues such as Taiwan Retrocession Day, national identity, ethnic identity, and the formal Taiwan independence movement.

History[]

Background[]

Japan had sought to expand its imperial control over Taiwan (formerly known as "Highland nation" (Japanese: 高砂国, Hepburn: Takasago-koku)) since 1592 when Toyotomi Hideyoshi undertook a policy of overseas expansion and extending Japanese influence southward.[3] Several attempts to invade Taiwan were unsuccessful, mainly due to disease and armed resistance by aborigines on the island. In 1609, the Tokugawa Shogunate sent Arima Harunobu on an exploratory mission of the island. In 1616, Murayama Toan led an unsuccessful invasion of the island.[4]

In November 1871, 69 people on board a vessel from the Kingdom of Ryūkyū were forced to land near the southern tip of Taiwan by strong winds. They had a conflict with local Paiwan aborigines, and many were killed. In October 1872, Japan sought compensation from the Qing dynasty of China, claiming the Kingdom of Ryūkyū was part of Japan. In May 1873, Japanese diplomats arrived in Beijing and put forward their claims; however, the Qing government immediately rejected Japanese demands on the ground that the Kingdom of Ryūkyū at that time was an independent state and had nothing to do with Japan. The Japanese refused to leave and asked if the Chinese government would punish those "barbarians in Taiwan". The Qing authorities explained that there were two kinds of aborigines in Taiwan: those directly governed by the Qing, and those unnaturalized "raw barbarians... beyond the reach of Chinese culture. Thus could not be directly regulated." They indirectly hinted that foreigners traveling in those areas settled by indigenous people must exercise caution. The Qing dynasty made it clear to the Japanese that Taiwan was definitely within Qing jurisdiction, even though part of that island's aboriginal population was not yet under the influence of Chinese culture. The Qing also pointed to similar cases all over the world where an aboriginal population within a national boundary was not under the influence of the dominant culture of that country.[5]

The Japanese nevertheless launched an expedition to Taiwan with a force of 3,000 soldiers in April 1874. In May 1874, the Qing dynasty began to send in troops to reinforce the island. By the end of the year, the government of Japan decided to withdraw its forces after realizing Japan was still not ready for a war with China.[citation needed]

The number of casualties for the Paiwan was about 30, and that for the Japanese was 543 (12 Japanese soldiers were killed in battle and 531 by disease).[citation needed]

Cession of Taiwan (1895)[]

By the 1890s, about 45 percent of Taiwan was under standard Chinese administration, while the remaining lightly populated regions of the interior were under aboriginal control. The First Sino-Japanese War broke out between Qing dynasty China and Japan in 1894 following a dispute over the sovereignty of Korea. Following its defeat, China ceded the islands of Taiwan and Penghu to Japan in the Treaty of Shimonoseki, signed on April 17, 1895. According to the terms of the treaty, Taiwan and Penghu (isles between 119˚E-120˚E and 23˚N-24˚N) were to be ceded to Japan in perpetuity. Both governments were to send representatives to Taiwan immediately after signing to begin the transition process, which was to be completed in no more than two months. Because Taiwan was ceded by treaty, the period that followed is referred by some as the "colonial period," while others who focus on the fact that it was the culmination of war refer to it as the "occupation period." The cession ceremony took place on board a Japanese vessel because the Chinese delegate feared reprisal from the residents of Taiwan.[6]

Though the terms dictated by Japan were harsh, it is reported that Qing China's leading statesman, Li Hongzhang, sought to assuage Empress Dowager Cixi by remarking: "birds do not sing and flowers are not fragrant on the island of Taiwan. The men and women are inofficious and are not passionate either."[7] The loss of Taiwan would become a rallying point for the Chinese nationalist movement in the years that followed. Arriving in Taiwan, the new Japanese colonial government gave inhabitants two years to choose whether to accept their new status as Japanese subjects or leave Taiwan.[8] Less than 10,000 out of a population of around 2.5 million chose to leave Taiwan.[9]

Early years (1895–1915)[]

The "early years" of Japanese administration on Taiwan typically refers to the period between the Japanese forces' first landing in May 1895 and the Ta-pa-ni Incident of 1915, which marked the high point of armed resistance. During this period, popular resistance to Japanese rule was high, and the world questioned whether a non-Western nation such as Japan could effectively govern a colony of its own. An 1897 session of the Japanese Diet debated whether to sell Taiwan to France.[10] During these years, the post of Governor-General of Taiwan was held by a military general, as the emphasis was on suppression of the insurgency.[citation needed]

In the early days of Japanese colonial rule, police were deployed to the cities to maintain order, often through brutal means, while the military was deployed to the countryside as a counter-insurgency and policing force. The brutality of early Japanese policing backfired and often inspired rebellion and insurrection instead of quashing it.[11]

In 1898, the Meiji government of Japan appointed Count Kodama Gentarō as the fourth Governor-General, with the talented civilian politician Gotō Shinpei as his Chief of Home Affairs, establishing the carrot and stick approach towards governance that would continue for several years.[8]

This marked the beginning of a colonial government (formally known as the Office of the Governor-General) dominated by the Japanese but subject to colonial law.

Gotō Shinpei reformed the policing system, and he sought to co-opt existing traditions to expand Japanese power. Out of the Qing baojia system, he crafted the Hoko system of community control. The Hoko system eventually became the primary method by which the Japanese authorities went about all sorts of tasks from tax collecting, to opium smoking abatement, to keeping tabs on the population. Under the Hoko system, every community was broken down into Ko, groups of ten neighboring households. When a person was convicted of a serious crime, the person's entire Ko would be fined. The system only became more effective as it was integrated with the local police.[11]

Under Gotō, police stations were established in every part of the island. Rural police stations took on extra duties with those in the aboriginal regions operating schools known as “savage children’s educational institutes” to assimilate aboriginal children into Japanese culture. The local police station also controlled the rifles which aboriginal men relied upon for hunting as well as operated small barter stations which created small captive economies.[11]

Japan's approach to ruling Taiwan could be roughly divided into two views. The first, supported by Gotō, held that from a biological perspective, the natives could not be completely assimilated. Thus, Japan would have to follow the British approach, and Taiwan would never be governed exactly the same way as the Home Islands but would be governed under a whole new set of laws. The opposing viewpoint was held by future Prime Minister Hara Takashi, who believed that the Taiwanese and Koreans were similar enough to the Japanese to be fully absorbed into Japanese society and was thus in favour of using the same legal and governmental approaches on the colonies as those used in the Home Islands.

Colonial policy towards Taiwan mostly followed the approach championed by Gotō during his tenure as Chief of Home Affairs between March 1898 and November 1906, and this approach continued to be in effect until Hara Takashi became prime minister in 1918. During this period, the colonial government was authorized to pass special laws and edicts while wielding complete executive, legislative, and military power. With this absolute power, the colonial government moved to maintain social stability while suppressing dissent.

Dōka: "Integration" (1915–1937)[]

The second period of Japanese rule is generally classified as being between the end of the 1915 Seirai Temple Incident, and the Marco Polo Bridge Incident of 1937, which began Japan's involvement in what would become World War II. World events during this period, such as World War I, would drastically alter the perception of colonialism in the Western world, and give rise to growing waves of nationalism amongst colonial natives, as well as the ideas of self determination. As a result, colonial governments throughout the world began to make greater concessions to natives, and colonial governance was gradually liberalized. Taiwan-born Xie Jishi became a first Foreign Minister of Manchukuo.[citation needed][relevant?]

The political climate in Japan was also undergoing changes during this time. In the mid-1910s the Japanese government had gradually democratized in what is known as the Taishō period (1912–26), where power was concentrated in the elected lower house of the Imperial Diet, whose electorate was expanded to include all adult males by 1925. In 1919, Den Kenjirō was appointed to be the first civilian Governor-General of Taiwan. Prior to his departure for Taiwan, he conferred with Prime Minister Hara Takashi, where both men agreed to pursue a policy of assimilation (同化, dōka), where Taiwan would be viewed as an extension of the Home Islands, and the Taiwanese would be educated to understand their role and responsibilities as Japanese subjects. The new policy was formally announced in October 1919.[citation needed]

This policy was continued by the colonial government for the next 20 years. In the process, local governance was instituted, as well as an elected advisory committee which included locals (though strictly in an advisory capacity), and the establishment of a public school system. Caning was forbidden as a criminal punishment, and the use of the Japanese language was rewarded. This contrasted sharply with the mostly hands-off approach taken by previous administrations towards local affairs, where the only government concerns were "railways, vaccinations, and running water".[citation needed]

By the 1920s modern infrastructure and amenities had become widespread, although they remained under strict government control, and Japan was managing Taiwan as a model colony.[12] However a distinct Taiwanese identity had also emerged which would cause problems for the Japanese colonizers.[13]

Chinese diplomacy[]

The Consulate-General of the Republic of China in Taihoku was a diplomatic mission of the government of the Republic of China (ROC) that opened April 6, 1931, and closed in 1945 after the handover of Taiwan to the ROC. Even after Formosa had been ceded to Japan by the Qing dynasty, it still attracted many Chinese immigrants after the concession. On May 17, 1930, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs appointed Lin Shao-nan to be the Consul-General[14] and Yuan Chia-ta as Deputy Consul-General.

Democracy[]

Taiwan also had seats in House of Peers.[15] Ko Ken'ei (辜顯榮, Gu Xianrong) and Rin Kendō (林獻堂, Lin Xiantang) were among the Taiwan natives appointed to the legislative body.

In the first half of the 20th century, Taiwanese intellectuals, led by New People Society, started a movement to petition to the Japanese Diet to establish a self-governing parliament in Taiwan, and to reform the government-general. The Japanese government attempted to dissuade the population from supporting the movement, first by offering the participants membership in an advisory Consulative Council, then ordered the local governments and public schools to dismiss locals suspected of supporting the movement. The movement lasted 13 years.[16] Although unsuccessful, the movement prompted the Japanese government to introduce local assemblies in 1935.[17]

Kōminka: "Subjects of the Emperor" (1937–1945)[]

Japanese rule in Taiwan was reinvigorated by the eruption of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 and ended along with the Second World War in 1945. With the rise of militarism in Japan in the mid-to-late 1930s, the office of Governor-General was again held by military officers, and Japan sought to use resources and material from Taiwan in the war effort. To this end, the cooperation of the Taiwanese would be essential, and the Taiwanese would have to be fully assimilated as members of Japanese society. As a result, earlier social movements were banned and the Colonial Government devoted its full efforts to the "Kōminka movement" (皇民化運動, kōminka undō), aimed at fully Japanizing Taiwanese society.[8]

Between 1936 and 1940, the Kōminka movement sought to build "Japanese spirit" (大和魂, Yamatodamashī) and Japanese identity amongst the populace, while the later years from 1941 to 1945 focused on encouraging Taiwanese to participate in the war effort. As part of the movement, the Colonial Government began to strongly encourage locals to speak the Japanese language, wear Japanese clothing, live in Japanese-style houses, "modernize" funeral practices by observing "Japanese-style" funerals (which was in fact ambiguous at the time)[18] and convert to Shintoism. In 1940, laws were also passed advocating the adoption of Japanese names.

With the expansion of the Pacific War, the government also began encouraging Taiwanese to volunteer for the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy in 1942, and finally ordered a full scale draft in 1945. In the meantime, laws were made to grant Taiwanese membership in the Japanese Diet, which theoretically would qualify a Taiwanese person to become the premier of Japan eventually.

As a result of the war, Taiwan suffered many losses including Taiwanese youths killed while serving in the Japanese armed forces, as well as severe economic repercussions from Allied bombing raids. By the end of the war in 1945, industrial and agricultural output had dropped far below prewar levels, with agricultural output 49% of 1937 levels and industrial output down by 33%. Coal production dropped from 200,000 metric tons to 15,000 metric tons.[19]

During WWII the Japanese authorities maintained prisoner of war camps in Taiwan. Allied prisoners of war (POW) were used as forced labor in camps throughout Taiwan with the camp serving the copper mines at Kinkaseki (now Jinguashi) being especially heinous.[20] Of the 430 Allied POW deaths across all fourteen Japanese POW camps on Taiwan, the majority occurred at Kinkaseki.[21]

Office of the Governor-General[]

As the highest colonial authority in Taiwan during the period of Japanese rule, the Office of the Governor-General of Taiwan was headed by a Governor-General of Taiwan appointed by Tōkyō. Power was highly centralized with the Governor-General wielding supreme executive, legislative, and judicial power, effectively making the government a dictatorship.[8]

Development[]

In its earliest incarnation, the Colonial Government was composed of three bureaus: Home Affairs, Army, and Navy. The Home Affairs Bureau was further divided into four offices: Internal Affairs, Agriculture, Finance, and Education. The Army and Navy bureaus were merged to form a single Military Affairs Bureau in 1896. Following reforms in 1898, 1901, and 1919 the Home Affairs Bureau gained three more offices: General Affairs, Judicial, and Communications. This configuration would continue until the end of colonial rule. The Japanese colonial government was responsible for building harbors and hospitals as well as constructing infrastructure like railroads and roads. By 1935 the Japanese expanded the roads by 4,456 kilometers, in comparison with the 164 kilometers that existed before the Japanese occupation. The Japanese government invested a lot of money in the sanitation system of the island. These campaigns against rats and unclean water supplies contributed to a decrease of diseases such as cholera and malaria.[22]

Governors-General[]

Throughout the period of Japanese rule, the Office of the Governor-General remained the de facto central authority in Taiwan. Formulation and development of governmental policy was primarily the role of the central or local bureaucracy.

In the 50 years of Japanese rule from 1895 to 1945, Tōkyō dispatched nineteen Governors-General to Taiwan. On average, a Governor-General served about 2.5 years. The entire colonial period can be further divided into three periods based on the background of the Governor-General: the Early Military period, the Civilian period, and the Later Military period.

Governors-General from the Early Military period included Kabayama Sukenori, Katsura Tarō, Nogi Maresuke, Kodama Gentarō, Sakuma Samata, Ando Sadami, and Akashi Motojirō. Two of the pre-1919 Governors-General, Nogi Maresuke and Kodama Gentarō, would become famous in the Russo-Japanese War. Andō Sadami and Akashi Motojirō are generally acknowledged to have done the most for Taiwanese interests during their tenures, with Akashi Motojirō actually requesting in his will that he be buried in Taiwan, which he indeed was.

The Civilian period occurred at roughly the same time as the Taishō democracy in Japan. Governors-General from this era were mostly nominated by the Japanese Diet and included Den Kenjirō, Uchida Kakichi, Izawa Takio, Kamiyama Mitsunoshin, Kawamura Takeji, Ishizuka Eizō, Ōta Masahiro, Minami Hiroshi, and Nakagawa Kenzō. During their tenures, the Colonial Government devoted most of its resources to economic and social development rather than military suppression.

The Governors-General of the Later Military period focused primarily on supporting the Japanese war effort and included Kobayashi Seizō, Hasegawa Kiyoshi, and Andō Rikichi.

- List of Governors-General of Taiwan

- Kabayama Sukenori (1895–96)

- Katsura Tarō (1896)

- Nogi Maresuke (1896–98)

- Kodama Gentarō (1898–1906)

- Sakuma Samata (1906–15)

- Andō Sadami (1915–18)

- Akashi Motojirō (1918–19)

- Den Kenjirō (1919–23)

- Uchida Kakichi (1923–24)

- Izawa Takio (1924–26)

- Kamiyama Mitsunoshin (1926–28)

- Kawamura Takeji (1928–29)

- Ishizuka Eizō (1929–31)

- Ōta Masahiro (1931–32)

- Minami Hiroshi (1932)

- Nakagawa Kenzō (1932–36)

- Kobayashi Seizō (1936–40)

- Kiyoshi Hasegawa (1940–44)

- Andō Rikichi (1944–45)

Chief of Home Affairs[]

Formally known as the Director of the Home Affairs Bureau, the Chief of Home Affairs (総務長官, Sōmu chōkan) was the primary executor of colonial policy in Taiwan, and the second most powerful individual in the Colonial Government.

Administrative divisions[]

Besides the Governor-General and the Chief of Home Affairs, the Office of the Governor-General was a strictly hierarchical bureaucracy including departments of law enforcement, agriculture, finance, education, mining, external affairs, and judicial affairs. Other governmental bodies included courts, corrections facilities, orphanages, police academies, transportation and port authorities, monopoly bureaus, schools of all levels, an agricultural and forestry research station, and the Taihoku Imperial University.

Administratively, Taiwan was divided into prefectures for local governance. In 1926, the prefectures were:

| Name | Area (km2) |

Population (1941) |

Modern district | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prefecture | Kanji | Kana | Rōmaji | |||

| Taihoku Prefecture | 台北州 | たいほくしゅう | Taihoku-shū | 4,594.2371 | 1,140,530 | Keelung City, New Taipei City, Taipei City, Yilan County |

| Shinchiku Prefecture | 新竹州 | しんちくしゅう | Shinchiku-shū | 4,570.0146 | 783,416 | Hsinchu City, Hsinchu County, Miaoli County, Taoyuan City |

| Taichū Prefecture | 台中州 | たいちゅうしゅう | Taichū-shū | 7,382.9426 | 1,303,709 | Changhua County, Nantou County, Taichung City |

| Tainan Prefecture | 台南州 | たいなんしゅう | Tainan-shū | 5,421.4627 | 1,487,999 | Chiayi City, Chiayi County, Tainan City, Yunlin County |

| Takao Prefecture | 高雄州 | たかおしゅう | Takao-shū | 5,721.8672 | 857,214 | Kaohsiung City, Pingtung County |

| Karenkō Prefecture | 花蓮港庁 | かれんこうちょう | Karenkō-chō | 4,628.5713 | 147,744 | Hualien County |

| Taitō Prefecture | 台東庁 | たいとうちょう | Taitō-chō | 3,515.2528 | 86,852 | Taitung County |

| Hōko Prefecture | 澎湖庁 | ほうこちょう | Hōko-chō | 126.8642 | 64,620 | Penghu County |

Annexation and armed resistance[]

Japan's annexation of Taiwan did not come about as the result of long-range planning. Instead, this action resulted from strategy during the war with China and from diplomacy carried out in the spring of 1895. Prime Minister Hirobumi's southern strategy, supportive of Japanese navy designs, paved the way for the occupation of Penghu Islands in late March as a prelude to the takeover of Taiwan. Soon after, while peace negotiations continued, Hirobumi and Mutsu Munemitsu, his minister of foreign affairs, stipulated that both Taiwan and Penghu were to be ceded by imperial China.[23]

Li Huang-chang, China's chief diplomat, was forced to accede to these conditions as well as to other Japanese demands, and the Treaty of Shimonoseki was signed on April 17, then duly ratified by the Qing court on 8 May. The formal transference of Taiwan and Penghu took place on a ship off the Kīrun coast on June 2. This formality was conducted by Li's adopted son, Li Ching-fang, and Admiral Kabayama Sukenori, a staunch advocate of annexation, whom Itō had appointed as governor-general of Taiwan.[24]

The annexation of Taiwan was also based on practical considerations of benefit to Japan. Tōkyō expected the large and productive island to furnish provisions and raw materials for Japan's expanding economy and to become a ready market for Japanese goods. Taiwan's strategic location was deemed advantageous as well. As envisioned by the navy, the island would form a southern bastion of defense from which to safeguard southernmost China and southeastern Asia. These considerations accurately forecast the major roles Taiwan would play in Japan's quest for power, wealth, and great empire.[25]

Most armed resistance against Japanese rule occurred during the first 20 years of colonial rule. This period of Han and aboriginal resistance is usually divided[by whom?] into three stages: the defense of the Republic of Formosa; guerilla warfare following the collapse of the Republic; and a final stage between the Hoppo uprising of 1907, and the Seirai Temple Incident of 1915. Afterwards, Han armed resistance was mostly replaced by peaceful forms of cultural and political activism, while the mountain aboriginals continued to carry out armed struggle such as in the Musha Incident in 1930.

Republic of Formosa[]

The decision by the Qing Chinese government to cede Taiwan to Japan with the Treaty of Shimonoseki caused a massive uproar in Taiwan. On 25 May 1895, a group of pro-Qing officials and local gentry declared independence from China, proclaiming a new Republic of Formosa with the goal of keeping Taiwan under Qing rule, choosing then Qing governor Tang Jingsong as their reluctant president. In response, Japanese forces landed in Keelung on 29 May, taking the city on 3 June. President Tang and his Vice-President Qiu Fengjia fled the island for mainland China the following day. Later in the same month, remaining supporters of the new Republic gathered in Tainan and selected Liu Yongfu as the second president. The local Taiwanese Han militia units were mobilized to counter the Japanese occupation. After a series of bloody conflicts between the Japanese and local Taiwanese forces, the Japanese had successfully seized Tainan by late October, inflicting heavy casualties on the Taiwanese side. Shortly afterwards, President Liu fled Taiwan for mainland China, bringing the 184-day history of the Republic to an end.

Guerrillas[]

"The cession of the island to Japan was received with such disfavour by the Chinese inhabitants that a large military force was required to effect its occupation. For nearly two years afterwards, a bitter guerrilla resistance was offered to the Japanese troops, and large forces – over 100,000 men, it was stated at the time – were required for its suppression. This was not accomplished without much cruelty on the part of the conquerors, who, in their march through the island, perpetrated all the worst excesses of war. They had, undoubtedly, considerable provocation. They were constantly attacked by ambushed enemies, and their losses from battle and disease far exceeded the entire loss of the whole Japanese army throughout the Manchurian campaign. But their revenge was often taken on innocent villagers. Men, women, and children were ruthlessly slaughtered or became the victims of unrestrained lust and rapine. The result was to drive from their homes thousands of industrious and peaceful peasants, who, long after the main resistance had been completely crushed, continued to wage a vendetta war, and to generate feelings of hatred which the succeeding years of conciliation and good government have not wholly eradicated." – The Cambridge Modern History, Volume 12[26]

Following the collapse of the Republic of Formosa, the Japanese Governor-General Kabayama Sukenori reported to Tōkyō that "the island is secured", and proceeded to begin the task of administration. However, in December a series of anti-Japanese uprisings occurred in northern Taiwan, and would continue to occur at a rate of roughly one per month. By 1902, however, most anti-Japanese activity amongst the ethnic Chinese population had died down. Along the way, 14,000 Taiwanese, or 0.5% of the population had been killed.[27] Taiwan would remain relatively calm until the Hoppo Uprising in 1907. The reason for the five years of calm is generally attributed[by whom?] to the colonial government's dual policy of active suppression and public works. Under this carrot-and-stick approach, most locals chose to watch and wait.

Ryō Tentei (廖添丁, Liao Tianding) became a Robin Hood-like figure for his opposition to the Japanese.

The 1930 "New Flora and Silva, Volume 2" said of the mountain Aboriginals that "the majority of them live in a state of war against Japanese authority".[28]

The Bunun and Atayal were described as the "most ferocious" Aboriginals, and police stations were targeted by Aboriginals in intermittent assaults.[29] By January 1915, all Aboriginals in northern Taiwan were forced to hand over their guns to the Japanese. However, head hunting and assaults on police stations by Aboriginals still continued after that year.[30][31] Between 1921 and 1929 Aboriginal raids died down, but a major revival and surge in Aboriginal armed resistance erupted from 1930 to 1933 for four years during which the Musha incident occurred and Bunun carried out raids, after which armed conflict again died down.[32] According to a 1933-year book, wounded people in the Japanese war against the Aboriginals numbered around 4,160, with 4,422 civilians dead and 2,660 military personnel killed.[33] According to a 1935 report, 7,081 Japanese were killed in the armed struggle from 1896 to 1933 while the Japanese confiscated 29,772 Aboriginal guns by 1933.[34]

In one of Taiwan's southern towns nearly 5,000 to 6,000 were slaughtered by Japanese in 1915.[35]

Seirai Temple Incident[]

The third and final stage of armed resistance began with the Hoppo uprising in 1907 in which Saisiyat Aboriginals and Hakka people revolted against the Japanese. Between this and the 1915 Seirai Temple Incident thirteen smaller armed uprisings took place. In many cases, conspirators were discovered and arrested before planned uprisings could even occur. Of the thirteen uprisings, eleven occurred after the 1911 Revolution in China, to which four were directly linked. Conspirators in four of the uprisings demanded reunification with China, conspirators in six planned to install themselves as independent rulers of Taiwan, and conspirators in one could not decide which goal to pursue. The objectives of the conspirators in the other two cases remain unclear.

It has been speculated[by whom?] that the increase in uprisings demanding independence rather than reunification was the result of the collapse of the Qing dynasty government in China, which deprived locals of a governmental figure with whom they were originally accustomed to identify.[36] Aboriginals and Han joined together to revolt during the Seirai Temple Incident under (余 清芳, Yu Qingfang). Multiple Japanese police stations were stormed by Aboriginal and Han Chinese fighters under (江 定, Jiang Ding) and Yo Seihō.[37]

Seediq resistance[]

Musha events[]

Starting from 1897, the Japanese began a road building program that brought them into the indigenous people's territory. This was seen as invasive. Contacts and conflicts escalated and some indigenous people were killed. In 1901, in a battle with the Japanese, indigenous people defeated 670 Japanese soldiers. As a result of this, in 1902, the Japanese isolated Musha.

Between 1914 and 1917, Japanese forces carried out an aggressive 'pacification' program killing many resisting people. At this time, leader Mōna Rudao tried to resist rule by Japan, but he failed twice because his plans were divulged. At his third attempt, he organized seven out of twelve groups to fight against the Japanese forces.

Shinjō events[]

(新城事件, Shinjō jiken) When Japanese soldiers raped some indigenous women, two leaders and twenty men killed thirteen Japanese soldiers.[38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45]

Truku War[]

The Japanese wanted to take over the Truku people. After eight years of investing the area, they attacked. Two thousand of the indigenous people resisted.[46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54]

Jinshikan events 1902[]

(人止関事件, Jinshikan jiken) After taking over the plain, Japanese gained control of Musha. Some of the Tgdaya people who resisted the Japanese were shot. Because of this, fighting broke out again.[55][56][57]

Shimaigen incident 1903[]

(姊妹原事件, Shimaigen jiken) In 1903 the Japanese launched a punitive expedition to seek revenge for their earlier loss at Jinshikan.[58][59][60][61][62]

Musha Incident[]

Direct police involvement in local administration was curtailed in urban areas, and elements of self-government were introduced on various levels. Moreover, the colonial law-codes were revamped. Most of the harsher punishments ordained by ritsurei enactments were or had already been abolished or suspended, and the Japanese Code of Criminal Procedure of 1922 became effective in the colony by 1924.[63] A year earlier, most provisions of Japan's civil and commercial law codes became applicable in Taiwan.[64] Such significant changes in governance reflected not only moderate influences emanating from Taisho Japan but also accommodation by the colonial authorities to economic and social development in Taiwan and, in general, to the more orderly conditions there. For with the exception of the brief Musha incident of 1930, when aroused Seediq tribesmen killed and injured some three hundred and fifty Japanese, armed resistance to colonial authority had ceased.[65]

Perhaps the most famous of all of the anti-Japanese uprisings, the Musha incident, occurred in the mostly aboriginal region of Musha (霧社) in Taichū Prefecture. On October 27, 1930, following escalation of an incident in which a Japanese police officer insulted a tribesman, over 300 Seediq aborigines under Chief Mōna Rudao attacked Japanese residents in the area. In the ensuing violence, 134 Japanese nationals and two ethnic Han Taiwanese were killed, and 215 Japanese nationals injured. The Han were mistaken for Japanese by the aboriginals since one of the victims, a Han girl, was wearing a Kimono. Many of the victims were attending an athletic festival at Musha Elementary School. In response, the colonial government ordered a military crackdown. In the two months that followed, most of the insurgents were either killed or committed suicide, along with their family members or fellow tribesmen. Several members of the government resigned over the incident, which proved to be the most violent of the uprisings during Japanese rule.

Local administration continued to be strict, however, and not all modifications in governance had liberal overtones. Special criminal statues relating to public order and peace preservation were introduced from Japan, for example.[64] These severe enactments also included governmental responses to the peaceful resistance developed in the colony: in particular, to the new modes of protest[which?] staged by leaders[citation needed] among the younger generation of Taiwanese.

Taifun incident[]

(大分事件, Taifun jiken) The Bunun Aboriginals under Chief Raho Ari engaged in guerrilla warfare against the Japanese for twenty years. Raho Ari's revolt, called the Taifun Incident was sparked when the Japanese implemented a gun control policy in 1914 against the Aboriginals in which their rifles were impounded in police stations when hunting expeditions were over. The revolt began at Taifun when a police platoon was slaughtered by Raho Ari's clan in 1915. A settlement holding 266 people called Tamaho was created by Raho Ari and his followers near the source of the Rōnō River and attracted more Bunun rebels to their cause. Raho Ari and his followers captured bullets and guns and slew Japanese in repeated hit and run raids against Japanese police stations by infiltrating over the Japanese "guardline" of electrified fences and police stations as they pleased.[66]

Kobayashi Incident[]

As a resistance to the long-term oppression by the Japanese government, many Taivoan people from Kōsen led the first local rebellion against Japan in July 1915, called the (Japanese: 甲仙埔事件, Hepburn: Kōsenho jiken). This was followed by a wider rebellion from Tamai in Tainan to Kōsen in Takao in August 1915, known as the Seirai Temple Incident (Japanese: 西来庵事件, Hepburn: Seirai-an jiken) in which more than 1,400 local people died or were killed by the Japanese government. Twenty-two years later, the Taivoan people struggled to carry on another rebellion; since most of the indigenous people were from Kobayashi, the resistance taking place in 1937 was named the Kobayashi Incident (Japanese: 小林事件, Hepburn: Kobayashi jiken).[67]

Economic and educational development[]

One of the most notable features of Japanese rule in Taiwan was the "top-down" nature of social change. While local activism certainly played a role, most of the social, economic, and cultural changes during this period were driven by technocrats in the colonial government. With the Colonial Government as the primary driving force, as well as new immigrants from the Japanese Home Islands, Taiwanese society was sharply divided between the rulers and the ruled.

Under the constant control of the colonial government, aside from a few small incidents during the earlier years of Japanese rule, Taiwanese society was mostly very stable. While the tactics of repression used by the Colonial Government were often very heavy handed, locals who cooperated with the economic and educational policies of the Governor-General saw a significant improvement in their standard of living. As a result, the population and living standards of Taiwan during the 50 years of Japanese rule displayed significant growth.

Economic[]

Taiwan's economy during Japanese rule was, for the most part, a standard colonial economy. Namely, the human and natural resources of Taiwan were used to aid the development of Japan, a policy which began under Governor-General Kodama and reached its peak in 1943, in the middle of World War II. From 1900 to 1920, Taiwan's economy was dominated by the sugar industry, while from 1920 to 1930, rice was the primary export. During these two periods, the primary economic policy of the Colonial Government was "industry for Japan, agriculture for Taiwan". After 1930, due to war needs the Colonial Government began to pursue a policy of industrialization.[8] Under the 7th governor, Akashi Motojirō, a vast swamp in central Taiwan was transformed into a huge dam in order to build a hydraulic power plant for industrialization. The dam and its surrounding area, widely known as Sun Moon Lake (日月潭, Nichigetsu-tan) today, has become a must-see for foreign tourists visiting Taiwan.

Although the main focus of each of these periods differed, the primary goal throughout the entire time was increasing Taiwan's productivity to satisfy demand within Japan, a goal which was successfully achieved. As part of this process, new ideas, concepts, and values were introduced to the Taiwanese; also, several public works projects, such as railways, public education, and telecommunications, were implemented. As the economy grew, society stabilized, politics was gradually liberalized, and popular support for the colonial government began to increase. Taiwan thus served as a showcase for Japan's propaganda on the colonial efforts throughout Asia, as displayed during the 1935 Taiwan Exposition.[citation needed]

Fiscal[]

Shortly after the cession of Taiwan to Japanese rule in September 1895, an Ōsaka bank opened a small office in Kīrun. By June of the following year the Governor-General had granted permission for the bank to establish the first Western-style banking system in Taiwan.

In March 1897, the Japanese Diet passed the "Taiwan Bank Act", establishing the Bank of Taiwan (台湾銀行 , Taiwan ginkō), which began operations in 1899. In addition to normal banking duties, the Bank would also be responsible for minting the currency used in Taiwan throughout Japanese rule. The function of central bank was fulfilled by the Bank of Taiwan.[68]

To maintain fiscal stability, the Colonial Government proceeded to charter several other banks, credit unions, and other financial organizations which helped to keep inflation in check.

Compulsory education[]

As part of the colonial government's overall goal of keeping the anti-Japanese movement in check, public education became an important mechanism for facilitating both control and intercultural dialogue. While secondary education institutions were restricted mostly to Japanese nationals, the impact of compulsory primary education on the Taiwanese was immense.

On July 14, 1895, Isawa Shūji was appointed as the first Education Minister, and proposed that the Colonial Government implement a policy of compulsory primary education for children (a policy that had not even been implemented in Japan at the time). The Colonial Government established the first Western-style primary school in Taihoku (the modern-day Shilin Elementary School) as an experiment. Satisfied with the results, the government ordered the establishment of fourteen language schools in 1896, which were later upgraded to become public schools. During this period, schools were segregated by ethnicity. Kōgakkō (公學校, public schools) were established for Taiwanese children, while Shōgakkō (小學校, elementary schools) were restricted to the children of Japanese nationals. Schools for aborigines were also established in aboriginal areas. Criteria were established for teacher selection, and several teacher training schools such as Taihoku Normal School were founded. Secondary and post-secondary educational institutions, such as Taihoku Imperial University were also established, but access was restricted primarily to Japanese nationals. The emphasis for locals was placed on vocational education, to help increase productivity.

The education system was finally desegregated in March 1941, when all schools (except for a few aboriginal schools) were reclassified as kokumin gakkō (國民學校, National schools), open to all students regardless of ethnicity. Education was compulsory for children between the ages of eight and fourteen. Subjects taught included Morals (修身, shūshin), Composition (作文, sakubun), Reading (讀書, dokusho), Writing (習字, shūji), Mathematics (算術, sanjutsu), Singing (唱歌, shōka), and Physical Education (體操, taisō).

By 1944, there were 944 primary schools in Taiwan with total enrollment rates of 71.3% for Taiwanese children, 86.4% for aboriginal children, and 99.6% for Japanese children in Taiwan. As a result, primary school enrollment rates in Taiwan were among the highest in Asia, second only to Japan itself.[8]

Population[]

As part of the emphasis placed on governmental control, the Colonial Government performed detailed censuses of Taiwan every five years starting in 1905. Statistics showed a population growth rate of 0.988 to 2.835% per year throughout Japanese rule. In 1905, the population of Taiwan was roughly 3 million.[69] By 1940 the population had grown to 5.87 million, and by the end of World War II in 1946 it numbered 6.09 million.

Transportation developments[]

The Office of the Governor-General also placed a strong emphasis on modernization of Taiwan's transportation systems, especially railways, and to a lesser extent, highways. As a result, reliable transit links were established between the northern and southern ends of the island, supporting the increasing population.

Railways[]

After Taiwan was ceded to Japan, the push car railways were introduced in Taiwan. The push car railways were in general service from 1895 to the late 1940s.

The Railway Department (predecessor of the modern Taiwan Railway Administration) was established on November 8, 1899, beginning a period of rapid expansion of the island's rail network. Perhaps the greatest achievement of this era was the completion of the Western Line, linking the major cities along the western corridor in 1908, reducing the travel time between northern and southern Taiwan from several days to a single day.

Also constructed during this time were the Tansui Line (淡水線, Tansui-sen), Giran Line (宜蘭線, Giran-sen), Heitō Line (屏東線, Heitō-sen), and (東港線, Tōkō-sen). Several private rail lines were also incorporated into the state owned system. Industrial lines such as the Arisan Forest Railway were also built. Plans were also drawn up for the North-Link Line, South-Link Line, as well as a line running through the mountains of central Taiwan, but were never realized due to technical difficulties as well as the outbreak of World War II. Private railways such as the Taiwan Sugar Railways (built to support the sugarcane industry), were also built.

Like many other government offices, the Railway Department was headed by technocrats. Many of the railways constructed during Japanese rule continue to be used today.

Highways[]

Compared to the rapid development of the rail system, the highway system saw much less attention. However, faced with increasing competition from motorcars, the Railway Ministry began purchasing and confiscating roads running parallel to railways.[citation needed]

Bus service was available in urban areas, but since the cities in Taiwan were quite small at the time, they remained secondary to rail service. Most bus routes of the time centered on local railway stations.

Social policy[]

While the idea of "special governance" promoted by Gotō dominated most policy decisions made by the colonial authorities, the ultimate goal remained modernization. Under these ideals, the colonial government, along with community groups, would gradually push to modernize Taiwanese society. The main thrust of these efforts targeted what were known as the "Three Bad Habits".

"Three Vices"[]

The "Three Vices" (三大陋習, Santai rōshū) considered by the Office of the Governor-General to be archaic and unhealthy were the use of opium, foot binding, and the wearing of queues.[70][71] Much like mainland China in the late nineteenth century, opium addiction was a serious social problem in Taiwan, with some statistics suggesting that over half of the ethnic Chinese population of Taiwan were users of the drug. The intentional disfigurement of female feet through binding was common to mainland Chinese and Taiwanese society at the time, and the queue hairstyle worn by the male population was forced upon Han Chinese by the Manchu rulers of the Qing dynasty (Queue Order).

Opium[]

Shortly after acquiring Taiwan in 1895, then Prime Minister Itō Hirobumi ordered that opium should be banned in Taiwan as soon as possible. However, due to the pervasiveness of opium addiction in Taiwanese society at the time, and the social and economic problems caused by complete prohibition, the initial hard line policy was relaxed in a few years. On January 21, 1897, the Colonial Government issued the Taiwan Opium Edict mandating a government monopoly of the opium trade, and restricting the sale of opium to those with government issued permits, with the ultimate goal of total abolition. The number of opium addicts in Taiwan quickly dropped from millions to 169,064 in 1900 (6.3% of the total population at the time), to 45,832 (1.3% of the population) by 1921. However, the numbers were still higher than those in nations where opium was completely prohibited. It was generally believed that one important factor behind the Colonial Government's reluctance to completely ban opium was the potential profit to be made through a state run narcotics monopoly.

In 1921, the Taiwanese People's Party accused colonial authorities before the League of Nations of being complicit in the addiction of over 40,000 people, while making a profit off opium sales. To avoid controversy, the Colonial Government issued the New Taiwan Opium Edict on December 28, and related details of the new policy on January 8 of the following year. Under the new laws, the number of opium permits issued was decreased, a rehabilitation clinic was opened in Taihoku, and a concerted anti-drug campaign launched.[72] Despite the directive, the government remained involved with the opium trade until June 1945.[73]

Foot binding[]

Foot binding was a practice fashionable in Ming and Qing dynasty China. Young girls' feet, usually at age six but often earlier, were wrapped in tight bandages so they could not grow normally, would break and become deformed as they reached adulthood. The feet would remain small and dysfunctional, prone to infection, paralysis, and muscular atrophy. While such feet were considered by some to be beautiful, others considered the practice to be archaic and barbaric. In concert with community leaders, the Colonial Government launched an anti-foot binding campaign in 1901. The practice was formally banned in 1915, with violators subject to heavy punishment. Foot binding in Taiwan died out quickly afterwards.

Queue[]

The Colonial Government took comparatively less action on queues. While social campaigns against wearing queues were launched, no edicts or laws were issued on the subject. With the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911, the popularity of queues also decreased.

Urban planning[]

The Colonial Government initially focused on pressing needs such as sanitation and military fortifications. Plans for urban development began to be issued in 1899, calling for a five-year development plan for most medium and large sized cities. The first phase of urban redevelopment focused on the construction and improvement of roads. In Taihoku, the old city walls were demolished, and the new Seimonchō area was developed for new Japanese immigrants.

The second phase of urban development began in 1901, focusing on the areas around the South and East Gates of Taihoku and the areas around the railway station in Taichū. Primary targets for improvement included roads and drainage systems, in preparation for the arrival of more Japanese immigrants.

Another phase began in August 1905 and also included Tainan. By 1917, urban redevelopment programs were in progress in over seventy cities and towns throughout Taiwan. Many of the urban plans laid out during these programs continue to be used in Taiwan today.

Public health[]

In the early years of Japanese rule, the Colonial Government ordered the construction of public clinics throughout Taiwan and brought in doctors from Japan to halt the spread of infectious disease. The drive was successful in eliminating diseases such as malaria, plague, and tuberculosis from the island. The public health system throughout the years of Japanese rule was dominated primarily by small local clinics rather than large central hospitals, a situation which would remain constant in Taiwan until the 1980s.

The Colonial Government also expended a great deal of effort in developing an effective sanitation system for Taiwan. British experts were hired to design storm drains and sewage systems. The expansion of streets and sidewalks, as well as building codes calling for windows allowing for air flow, mandatory neighborhood cleanups, and quarantine of the ill also helped to improve public health.

Public health education also became important in schools as well as in law enforcement. The Taihoku Imperial University also established a Tropical Medicine Research Center, and formal training for nurses.

Aborigines[]

According to the 1905 census, the aboriginal population included 45,000+ plains aborigines[citation needed] who were almost completely assimilated into Han Chinese society, and 113,000+ mountain aborigines.[74] Japanese aboriginal policy focused primarily on the unassimilated latter group, known in Japanese as Takasago-zoku (高砂族).

The aborigines were subject to modified versions of criminal and civil law. As with the rest of the Taiwanese population, the ultimate goal of the Colonial Government was to assimilate the aborigines into Japanese society through a dual policy of suppression and education. This Japanese policy proved its worth during World War II, when aborigines called to service proved to be the most daring soldiers the empire had ever produced. Their legendary bravery is celebrated by Japanese veterans even today. Many of them would say they owe their survival to the Takasago Volunteers (高砂兵, Takasago-hei).

Religion[]

Throughout most of Japanese colonial rule, the Colonial Government chose to promote the existing Buddhist religion over Shintoism in Taiwan. It was believed that used properly, religion could accelerate the assimilation of the Taiwanese into Japanese society.

Under these circumstances, existing Buddhist temples in Taiwan were expanded and modified to accommodate Japanese elements of the religion, such as worship of Ksitigarbha (popular in Japan but not Taiwan at the time). The Japanese also constructed several new Buddhist temples throughout Taiwan, many of which also ended up combining aspects of Daoism and Confucianism, a mix which still persists in Taiwan today.

In 1937 with the beginning of the Kōminka movement, the government began the promotion of Shintoism and the limited restriction of other religions.

Military service[]

For most of the Japanese colonial period, the Taiwanese were banned from service in the military of Imperial Japan. However, starting in 1937, Taiwanese were permitted to enlist, for support duties. In 1942 the Imperial Army's and in 1943 the Imperial Navy's respective: Special Volunteers Acts allowed Taiwanese to volunteer for those services' combat arms. In 1944 and 1945 respectively those programs were replaced in Taiwan with systematic conscription. 207,183 Taiwanese served in the military of Imperial Japan. In addition, thousands of aboriginal men volunteered from 1937 onwards, eventually being taken out of support and placed in special commando type units due to their skills in jungle warfare.

The Japanese used Aboriginal and Han Taiwanese women as "comfort women" who served as sex slaves to Japanese troops, along with women from other countries under Japanese colonialism such as Korea and the Philippines.[76]

A total of 30,304 servicemen, or 15% of those recruited and conscripted from Taiwan, were killed or presumed killed in action. 2nd Lt. Lee Teng-hui (Japanese name: 岩里 政男, Iwasato Masao) of the Imperial Japanese Army later went on to become the Republic of China's president. His elder brother, (李 登欽; Japanese name: 岩里 武則, Iwasato Takenori), was killed in the Philippines and is enshrined in death along with at least 26,000 other Taiwanese Imperial Japan servicemen and hundreds of Takasago Volunteers, killed or presumed killed in action, in the Yasukuni Shrine in Tōkyō, Japan, where everyone who died fighting for modern Japan is honored.

Culture[]

After 1915, armed resistance against the Japanese colonial government nearly ceased. Instead, spontaneous social movements became popular. The Taiwanese people organized various modern political, cultural and social clubs, adopting political consciousness with clear intentions to unite people with sympathetic sensibilities. This motivated them to strive for the common targets set up by the social movements. These movements also encouraged improvements in social culture.

Besides Taiwanese literature, which connected with the social movements of the time, the aspect of Western culture which Taiwan most successfully adopted was the arts. Many famous works of art came out during this time.

Popular culture led by movies, popular music and puppet theater prevailed for the first time in Taiwan during this period.

Literature[]

The period of the second half of the colonial period, 1895 to 1945, is highly remarked as political stability and economic growth which accelerated modernization in Taiwan. The competition between the Japanese colonial Government-General and the native Taiwanese elite in the course of its modernization drew many young Taiwanese dream of being artists in a way of provoking improvement of their social status or cultivation of new knowledge which is more suitable to a modern society. Therefore, due to the trend of the campaign for modernization in Taiwan, many young native Taiwanese students went to study abroad, mostly in Japan from the late 1910s and some went to Paris in the 1930s. And indeed they became the pioneers in the era of the flourish cultural movement in Taiwan. It is irrefutable that literature had extraordinary importance in a socio-political and cultural context in the period from the 1920s to around the 1930s with the growing stimulation between writers and painters through shared interest in learning about modernization.[77] The group of artists, painters including some major artists (陳 清汾, Chen Qingfen), Gan Suiryū (顔 水龍, Yan Shuilong), Yō Sasaburō (楊 佐三郎, Yang Zuosanlang) and Ryū Keishō (劉 啟祥, Liu Qixiang), are characterized by westernized artistic expression and their own interpretation of time and place which represents a modern political and as well as cultural movement that were emerged by the landed-gentry who strongly resist against the Japanese colonial governors. One of the Japanese art critics recounts that the steady economic growth and great increase of public interest in art with numerous art exhibitions by single and group artists had attracted both Taiwanese and Taiwan-born Japanese artists return to Taiwan and share their works with audiences.[78]

Taiwanese students studying in Tōkyō firstly restructured in 1918, later renamed the New People Society (新民会, Shinminkai) after 1920, and this was the manifestation for various upcoming political and social movements in Taiwan. Many new publications, such as "Taiwanese Literature & Art" (1934) and "New Taiwanese Literature" (1935), started shortly thereafter. These led to the onset of the vernacular movement in the society at large as the modern literary broke away from the classical forms of ancient poetry. In 1915, this group of people, led by Rin Kendō made an initial and large financial contribution on establishing the first middle school in Taichū for the aboriginals and Taiwanese[79] and furthermore, they actively engaged to proclaim modernization, the cultural enlightenment and welfare of the island. They were passionate in delivering their political perspective in all sorts of forum covering lectures, seminars, concerts and plays for the population, maybe focusing on enthusiastic younger art students, being held in each season in almost every year. But shortly after, the oversea students returned to the island and they vigorously started to spread the ideas of socialist and proletarian, hence the working class necessitated changes social conditions. In the book of Wenhua xiehui de chengi yu fenlie, Zhang states that in early 1927, the association was broken up and eventually taken over by aggressive proletarian fractions. Many scholars acknowledged possible connections of this movement with the May Fourth Movement in China.

Literature movements did not disappear even when they were under censorship by the colonial government. In the early 1930s, a famous debate on Taiwanese rural language unfolded formally. This event had numerous lasting effects on Taiwanese literature, language and racial consciousness. In 1930, Taiwanese-Japanese resident Kō Sekki (黄 石輝, Huang Shihui) started the debate on rural literature in Tōkyō. He advocated that Taiwanese literature should be about Taiwan, have impact on a wide audience, and use Taiwanese Hokkien. In 1931, Kaku Shūsei (郭秋生, Guo Quisen), a resident of Taihoku, prominently supported Kō's viewpoint. Kaku started the Taiwanese Rural Language Debate, which advocated literature published in Taiwanese. This was immediately supported by Rai Wa (頼 和, Lai He), who is considered as the father of Taiwanese literature. After this, dispute as to whether the literature of Taiwan should use Taiwanese or Chinese, and whether the subject matter should concern Taiwan, became the focus of the New Taiwan Literature Movement. However, because of the upcoming war and the pervasive Japanese cultural education, these debates could not develop any further. They finally lost traction under the Japanization policy set by the government.[80]

In the two years after 1934, progressive Taiwanese writers gathered up and established the and New Taiwanese Literature. This literature and art movement was political in its implications. Also many historians highlights developments in modern drama and literature with the intimate integration between the art worlds of Tōkyō and Taihoku in the 1930s. From 1935 literacy writers and visual artists began to closely stimulate each other and looked to society for support. Mostly the novels were renowned for its distinct nationalist and social realistic expression whilst painting haven't produced works that merely decorators of the colonial period.

After the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in 1937, the government of Taiwan immediately instituted "National Spirit General Mobilization", which formally commenced the Japanization policy.

Taiwanese writers could then only rely on organizations dominated by Japanese writers, for example the "Taiwanese Poet Association" which was established in 1939, and the "Association of Taiwanese Literature & Art", expanded in 1940.[80] This is because after the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war, re-introduction of military rule in 1937 terminated the development of art and cultural movement in Taiwan.

The movement of literature of modern Taiwan could be simplified by the two major trends; revitalized Chinese writing and modern literature in Japanese language.

Taiwanese literature mainly focused on the Taiwanese spirit and the essence of Taiwanese culture. People in literature and the arts began to think about issues of Taiwanese culture, and attempted to establish a culture that truly belonged to Taiwan. The significant cultural movement throughout the colonial period were led by the young generation who were highly educated in formal Japanese schools. Education played such a key role in supporting the government and to a larger extent, developing economic growth of Taiwan. However, despite the government prime effort in elementary education and normal education, there was a limited number of middle schools, approximately 3 across the whole country, so the preferred choices for graduates were leaving for Tōkyō or other cities to get an education. The foreign education of the young students was carried out solely by individuals' self-motivation and support from family. Education abroad got its popularity, particularly from Taichū prefecture, with the endeavor for acquiring skills and knowledge of civilization even under the situation of neither the colonial government nor society being able to guarantee their bright future; with no job plan for these educated people after their return.[81]

Western art[]

During the Qing dynasty, the concept of Western art did not exist in Taiwan. Painting was not a highly respected occupation, and even Chinese landscape painting was undeveloped. When the Japanese began their colonization of Taiwan in 1895, they brought in a new educational system which introduced Western and Japanese art education. This not only set the basis for the future development of art appreciation in Taiwan, it also produced various famous artists. Painter and instructor Ishikawa Kin'ichirō contributed immensely in planning the training of new art teachers. He personally instructed students and encouraged them to travel to Japan to learn the more sophisticated techniques of art.

In 1926, a Taiwanese student in Japan named Chin Chōha (陳 澄波, Chen Chengbo) published a work titled "Outside of Kagi Street" (嘉義街の外, Kagi-gai no soto). His work was selected for display in the seventh . This was the first Western-style work by a Taiwanese artist to be included in a Japanese exhibition. Many other works were subsequently featured in the Imperial Japanese Exhibitions and other exhibitions. These successes made it easier for the arts to become widespread in Taiwan. Ironically, the Japanese-appreciated Chen was executed by the Chinese after World War II without trial for being a "bandit".

What really established the arts in Taiwan was the introduction of official Japanese exhibitions in Taiwan. In 1927, the governor of Taiwan, along with artists Ishikawa Kin'ichirō, and (ja:木下靜涯) established the .[82] This exhibition was held sixteen times from 1938 to 1945. It cultivated the first generation of Taiwanese western artists. The regional Taiwanese art style developed by the exhibition still affected various fields, e.g. art, art design, and engineering design, even after the war.

Cinema[]

From 1901 to 1937, Taiwanese cinema was influenced immensely by Japanese cinema. Because of Taiwan's status as a Japanese colony, the traditions of Japanese movies were generally accepted by Taiwanese producers. For instance, the use of a benshi (narrator of silent films), which was a very important component of the film-going experience in Japan, was adopted and renamed piansu by the Taiwanese. This narrator was very different from its equivalent in the Western world. It rapidly evolved into a star system. In fact, people would go to see the very same film narrated by different benshi, to hear the other benshi's interpretation. A romance could become a comedy or a drama, depending on the narrator's style and skills.

The first Taiwan-made film was a documentary produced in February 1907 by , with a group of photographers that traveled through various areas in Taiwan. Their production was called "Description of Taiwan", and it covered through subjects such as city construction, electricity, agriculture, industry, mining, railways, education, landscapes, traditions, and conquest of aborigines. The first movie drama produced by Taiwanese was called "Whose Fault?" in 1925, produced by the Association of Taiwanese Cinema Research. Other types of films including educational pieces, newsreels and propaganda also helped form the mainstream of local Taiwanese movie productions until the defeat of Japan in 1945. Sayon's Bell, which depicted an aboriginal maid helping Japanese, was a symbolic production that represents these types of films.

In 1908, Takamatsu Toyojirō settled in Taiwan and began to construct theaters in the main cities. Takamatsu also signed with several Japanese and foreign movie companies and set up institutionalized movie publication. In 1924, theaters in Taiwan imported advanced intertitle technique from Japan, and the cinema in Taiwan grew more prominent. In October 1935, a celebration of the fortieth anniversary of annexation in Taiwan was held. The year after, Taihoku and Fukuoka were connected by airway. These two events pushed the Taiwanese cinema into its golden age.

Popular music[]

Popular music in Taiwan was established in the 1930s. Although published records and popular songs already existed in Taiwan before the 1930s, the quality and popularity of most of them was very poor. This was mainly because popular songs at the time differed slightly from traditional music like folk songs and Taiwanese opera. However, because of the rapid development of cinema and broadcasting during the 1930s, new popular songs that stepped away from traditional influences began to appear and become widespread in a short period of time.

The first accepted eminent popular song in Taiwan collocated with the Chinese movie, The Peach Girl (桃花泣血記), produced by Lianhua Productions, starring Ruan Lingyu, screened in Taiwan theaters in 1932. Hoping to attract more Taiwanese viewers, the producers requested Taiwanese composers (詹 天馬, Zhan Tianma) and (王 雲峰, Wang Yunfeng) to compose a song with the same title. The song that came out was a major hit and achieved success in record sales. From this period on, Taiwanese popular music with the assistance of cinema began to rise.

Puppet theater[]

Many Hokkien-speaking immigrants entered Taiwan during the 1750s, and with them they brought puppet theatre. The stories were based mainly on classical books and stage dramas and were very refined. Artistry focused on the complexity of the puppet movements. Musical accompaniment was generally Nankan (南管, Nanguan) and Hokkan (北管, Beiguan) music. According to the Records of Taiwan Province, Nankan was the earliest form of puppet theatre in Taiwan. Although this kind of puppet theatre fell out of the mainstream, it can still be found in a few troupes around the city of Taipei today.

During the 1920s, bukyō (武俠, wuxia) puppet theatre (i.e. based on martial arts) gradually developed. The stories were the main difference between traditional and bukyō puppet theatre. Based on new, popular bukyō novels, performances focused on the display of unique martial arts by the puppets. The representative figures during this era were Kō Kaitai (黄 海岱, Huang Haidai) of Goshūen (五洲園, Wuzhouyuan) and (鍾 任祥, Zhong Renxiang) of Shinkōkaku (新興閣, Xinxingge). This puppet genre began its development in Kobi and Seira towns of Tainan Prefecture, and was popularized in southern-central Taiwan. Kō Kaitai's puppet theatre was narrated in Hokkien, and included poems, historical narrative, couplets and riddles. Its performance blended Hokkan, Nankan, Randan (乱弾, Luantan), Shōon (正音, Zhengyin), Kashi (歌仔, Gezi) and Chōchō (潮調, Chaodiao) music.

After the 1930s, the Japanization policy affected puppet theatre. The customary Chinese Beiguan was forbidden, and was replaced with Western music. The costumes and the puppets were a mixture of Japanese and Chinese style. The plays often included Japanese stories like Mito Kōmon and others, with the puppets dressed in Japanese clothing. Performances were presented in Japanese. These new linguistic and cultural barriers reduced public acceptance, but introduced techniques which subsequently influenced the future development of the , including music and stage settings.

During this era, the world of puppet theatre in southern Taiwan had the Five Great Pillars (五大柱, Godaichū) and Four Great Celebrities (四大名芸人, Shidaimeigeinin). The Five Great Pillars referred to Kō Kaitai, Shō Ninshō, (黄 添泉, Huang Tianquan), (胡 金柱, Hu Jinzhu) and (盧 崇義, Lu Chongyi); the Four Great Celebrities referred to Kō Tensen, Ro Sūgi, (李 土員, Li Tuyuan) and (鄭 全明, Zheng Chuanming).

Baseball[]

The Japanese also brought baseball to Taiwan. There were baseball teams in elementary schools as well as public schools, and the Japanese built baseball fields such as Tainan Stadium. It became such a widespread sport that, by the early 1930s, nearly all major secondary schools and many primary schools had established representative baseball teams. The development of the game in Taiwan culminated when a team from Kagi Agricultural and Forestry School, an agriculture and forestry high school, ranked second in Japan's Kōshien national high-school baseball tournament. One legacy of this era today are the careers of several professional baseball players, such as Chien-Ming Wang, Hong-Chih Kuo, Tzu-Wei Lin, and Chien-Ming Chiang.

Change of governing authority[]

With the end of World War II, Taiwan was placed under the administrative control of the Republic of China by the Allies of World War II after 50 years of colonial rule by Japan. Chen Yi, the ROC Chief Executive of Taiwan, arrived on October 24, 1945, and received the last Japanese Governor-General, Andō Rikichi, who signed the document of surrender on the next day, which was proclaimed by Chen as "Retrocession Day". This turned out to be legally controversial since Japan did not renounce its sovereignty over Taiwan until April 28, 1952, with the coming into force of the San Francisco Peace Treaty, which further complicated the political status of Taiwan. As a result, use of the term "Retrocession of Taiwan" (Chinese: 臺灣光復; pinyin: Táiwān guāngfù) is less common in modern Taiwan.

Background[]

At the Cairo Conference of 1943, the Allies adopted a statement declaring that Japan would give up Taiwan at the end of the war. In April 1944, the ROC government at the wartime capital of Chongqing established the Taiwan Research Committee (臺灣調查委員會; Táiwān diàochá wěiyuánhuì) with Chen Yi as chairman. Shortly afterwards, the committee reported its findings on the economy, politics, society, and military affairs of Taiwan to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek.

Following the war, opinion in the ROC government was split as to the administration of Taiwan. One faction supported treating Taiwan in the same way as other Chinese territories occupied by the Japanese during World War II, creating a Taiwan Province. The other faction supported establishing a special administrative region in Taiwan with special military and police powers. In the end, Chiang Kai-shek chose to take Chen Yi's suggestion of creating a special 2000 man "Office of the Chief Executive of Taiwan Province" (臺灣省行政長官公署; Táiwān Shěng Xíngzhèng Zhǎngguān Gōngshǔ) to handle the transfer.

Japan surrendered to the Allies on August 14, 1945. On August 29, Chiang Kai-shek appointed Chen Yi as Chief Executive of Taiwan Province, and announced the creation of the Office of the Chief Executive of Taiwan Province and Taiwan Garrison Command on September 1, with Chen Yi also as the commander of the latter body. After several days of preparation, an advance party moved into Taihoku on October 5, with more personnel from Shanghai and Chongqing arriving between October 5 and 24. By 1938 about 309,000 Japanese lived in Taiwan.[83] Between the Japanese surrender of Taiwan in 1945 and April 25, 1946, the Republic of China forces repatriated 90% of the Japanese living in Taiwan to Japan.[84]

Surrender ceremony[]

The formal surrender of Japanese forces on Taiwan occurred on the morning of October 25, 1945, in Taihoku City Hall (modern Zhongshan Hall). The Office of the Governor-General of Taiwan formally surrendered to the Allies of World War II. On the same day, the Office of the Chief Executive began functioning from the building which now houses the ROC Executive Yuan.

See also[]

- History of Taiwan

- Japan–Taiwan relations

- Japanese opium policy in Taiwan (1895–1945)

- Korea under Japanese rule

- Political divisions of Taiwan (1895–1945)

- Knowing Taiwan

- Remains of Taipei prison walls

- Taiwan under Qing rule

- Taiwanese Imperial Japan Serviceman

- Taiwanese Resistance to the Japanese Invasion (1895)

- Takasago Volunteers

Notes[]

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ Pastreich, Emanuel (July 2003). "Sovereignty, Wealth, Culture, and Technology: Mainland China and Taiwan Grapple with the Parameters of "Nation State" in the 21st Century". Program in Arms Control, Disarmament, and International Security, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. OCLC 859917872. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Chen, C. Peter. "Japan's Surrender". World War II Database. Lava Development, LLC. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- ^ Huang, Fu-san (2005). "Chapter 3". A Brief History of Taiwan. ROC Government Information Office. Archived from the original on August 1, 2007. Retrieved July 18, 2006.

- ^ Frei, Henry P.,Japan's Southward Advance and Australia, Univ of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, ç1991. p.34 - "...ordered the Governor of Nagasaki, Murayama Toan, to invade Formosa with a fleet of thirteen vessels and around 4000 men. Only a hurricane thwarted this effort and forced their early return"

- ^ Zhao, Jiaying (1994). 中国近代外交史 [A Diplomatic History of China] (in Chinese) (1st ed.). Taiyuan: 山西高校联合出版社. ISBN 9787810325776.

- ^ Davidson (1903), p. 293.

- ^ "男無情,女無義,鳥不語,花不香" (nán wú qíng, nǚ wú yì, niǎo bú yǔ, huā bú xiāng). (This expression has also been attributed to the Qianlong Emperor.)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Huang, Fu-san (2005). "Chapter 6: Colonization and Modernization under Japanese Rule (1895–1945)". A Brief History of Taiwan. ROC Government Information Office. Archived from the original on March 17, 2007. Retrieved July 18, 2006.

- ^ Dawley, Evan. "Was Taiwan Ever Really a Part of China?". thediplomat.com. The Diplomat. Retrieved June 10, 2021.

- ^ Shaohua Hu (2018). Foreign Policies toward Taiwan. Routledge. pp. 161–. ISBN 978-1-138-06174-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Crook, Steven. "Highways and Byways: Handcuffed to the past". www.taipeitimes.com. Taipei Times. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ van der Wees, Gerrit. "Has Taiwan Always Been Part of China?". thediplomat.com. The Diplomat. Retrieved December 2, 2020.

- ^ Dawley, Evan. "A Celebrity Apology and the Reality of Taiwan". hnn.us. History News Network. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ Lan, Shi-chi, Nationalism in Practice: Overseas Chinese in Taiwan and the Taiwanese in China, 1920s and 1930s (PDF), Academia Sinica Institute of Modern History, retrieved March 27, 2014

- ^ Yeh, Lindy (April 15, 2002). "The Koo family: a century in Taiwan". Taipei Times. p. 3. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- ^ I-te chen, Edward. "Formosan Political Movements Under Japanese Colonial Rule, 1914-1937". The Journal of Asian Studies. 31 (3): 477–497. doi:10.2307/2052230.