Apocalypto

| Apocalypto | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Mel Gibson |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Dean Semler |

| Edited by | John Wright |

| Music by | James Horner |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Buena Vista Pictures Distribution |

Release date |

|

Running time | 138 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | Yucatec Maya |

| Budget | $40 million[2] |

| Box office | $120.7 million[2] |

Apocalypto (/əˌpɒkəˈlɪptoʊ/) is a 2006 American epic historical adventure film produced, co-written, and directed by Mel Gibson. The film features a cast of Native American and Indigenous Mexican actors consisting of Rudy Youngblood, Raoul Trujillo, Mayra Sérbulo, Dalia Hernández, Ian Uriel, Gerardo Taracena, Rodolfo Palacios, Bernardo Ruiz Juarez, Ammel Rodrigo Mendoza, Ricardo Diaz Mendoza, and Israel Contreras. All of the ethnic tribes and peoples depicted in the film were Maya, as Gibson wanted to depict the Mayan city built for the story as an "unknown world" to the character (Jaguar Paw). Similar to Gibson's earlier film The Passion of the Christ, all dialogue is in a modern approximation of the ancient language of the setting. Here, the Indigenous Yucatec Mayan language is spoken with subtitles, which sometimes refer to the language as Mayan. This was the last film Gibson directed until 2016's Hacksaw Ridge ten years later.

Set in Yucatán, Mexico, around the year 1502, Apocalypto portrays the hero's journey of a young man named Jaguar Paw, a late Mesoamerican hunter and his fellow tribesmen who are captured by an invading force. After the devastation of their village, they are brought on a perilous journey to a Mayan city for human sacrifice at a time when the Mayan civilization is in decline. The film was a box office success, grossing over $120 million worldwide, and received mostly positive reviews, with critics praising Gibson's direction, Dean Semler's cinematography, and the performances of the cast, though the portrayal of Mayan civilisation and historical accuracy were criticized. The film was distributed by Buena Vista Pictures in North America and Icon Film Distribution in the United Kingdom and Australia.

Plot[]

While hunting in the Mesoamerican rainforest, Jaguar Paw, his father Flint Sky, and their fellow tribesmen encounter a procession of refugees fleeing warfare. The group's leader explains that their lands were ravaged and they seek a new beginning. He asks for permission to pass through the jungle. Flint Sky comments to his son that the visitors were sick with fear and urges him to never allow fear to infect him. Later that night, the tribe gather around an elder who shares a story that cryptically foreshadows the events of the film: an individual who is consumed by an emptiness that cannot be satisfied, despite having all the gifts of the world offered to him, will continue blindly taking until there is nothing left in the world for him to take and the world is no more.

At sunrise the next morning, the tribe's village suffers a raid led by Zero Wolf. Huts are set on fire, many villagers are killed, and the surviving adults are taken prisoner. During the attack, Jaguar Paw lowers his pregnant wife Seven and their young son Turtles Run into a pit. Returning to the fight, Jaguar Paw nearly kills the sadistic raider Middle Eye, but is captured. When Middle Eye realizes that Flint Sky is Jaguar Paw's father, he kills Flint Sky and mockingly renames Jaguar Paw "Almost". The raiders tie the captives together and set out on a long forced march through the jungle, leaving the children behind to fend for themselves. Seven and Turtles Run remain trapped in the pit after a suspicious raider cuts the vine leading out of it.

On the journey, Cocoa Leaf, a badly wounded captive, almost falls off a cliff with the other captives dragged after him. After climbing back to safety, he is killed by Middle Eye, eliciting anger from Zero Wolf, who threatens his fellow raider with death if he kills another captive without permission. As the party approaches the Mayan city of the raiders' origin, they encounter razed forests and vast fields of failed maize crops, alongside villages decimated by an unknown disease. They then pass a little girl infected with the plague who prophesies the end of the Mayan world. Once the raiders and captives reach the city, the females are sold into slavery while the males are escorted to the top of a step pyramid to be sacrificed before the Mayan king and queen.

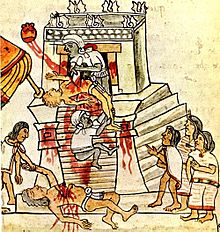

Two members of the party are sacrificed, but as Jaguar Paw is laid out on the altar, a solar eclipse gives the high priest, who is performing the sacrifices by cutting out the captives' hearts, pause. The Mayans take the event as an omen that the gods are satisfied, even though a glance shared between the high priest and the king implies that the true purpose behind the sacrifices is that they are a political tool wielded by the elite to pacify the unsuspecting and fearful masses, who are suffering from famine, disease, and poverty. Nevertheless, the ritual ceremony comes to an end and the remaining captives are spared. They are then taken by the raiders to be used as target practice and offered freedom if they can run to safety. Jaguar Paw suffers an arrow wound, but escapes into the jungle, killing Zero Wolf's son Cut Rock in the process. Zero Wolf, Middle Eye, and seven others chase after him. Fleeing back into the jungle, Jaguar Paw remembers his father's lesson about fear and resolves to kill his pursuers. The raiders are killed off one by one (including Zero Wolf and Middle Eye), either by traps laid out by Jaguar Paw or natural hazards until there are only two left.

The drought breaks and heavy rain begins to fall, threatening to drown Jaguar Paw's family, who are still trapped in the pit, despite their attempts to escape. Seven gives birth to another son, who is born under the surface of the dangerously rising water. Meanwhile, the two remaining raiders chase Jaguar Paw out of the undergrowth towards the coast. As they come to the beach all three are suddenly halted in their tracks and stare in awe at something before them. It's revealed the Spanish and their ships have arrived at the new world, as the conquistadors make their way to the shore. Jaguar Paw turns and flees while the raiders stand confounded by the alien invaders. Jaguar Paw returns just in time to save his family from the flooding pit and is overjoyed at the sight of his newborn son.

Later, the reunited family looks out over the water at the Spanish ships. Jaguar Paw decides not to approach the strangers, and the family departs into the jungle to seek a new beginning.

Cast[]

- Rudy Youngblood as Jaguar Paw

- Dalia Hernández as Seven

- Itandehui Gutiérrez as Wife

- Jonathan Brewer as Blunted

- Mayra Serbulo as Young Woman

- Morris Birdyellowhead as Flint Sky

- Carlos Emilio Báez as Turtles Run

- Amílcar Ramírez as Curl Nose

- Israel Contreras as Smoke Frog

- Israel Ríos as Cocoa Leaf

- María Isabel Díaz as Mother-in-Law

- Iazúa Laríos as Sky Flower

- Raoul Trujillo as Zero Wolf

- Gerardo Taracena as Middle Eye

- Rodolfo Palacios as Snake Ink

- Ariel Galván as Hanging Moss

- Fernando Hernández as High Priest

- Rafael Vélez as Maya King

- Diana Botello as Maya Queen

- Bernardo Ruiz Juárez as Drunkards Four

- Ricardo Díaz Mendoza as Cut Rock

- Richard Can as Ten Peccary

- Carlos Ramos as Monkey Jaw

- Ammel Rodrigo Mendoza as Buzzard Hook

- Marco Antonio Argueta as Speaking Wind

- Aquetzali García as Oracle boy

- Gabriela Marambio as Close-Up Mayan Girl

- María Isidra Hoil as Sick Oracle Girl

- Abel Woolrich as Laughing Man

Production[]

Screenplay[]

Screenwriter and co-producer Farhad Safinia first met Mel Gibson while working as an assistant during the post-production of The Passion of the Christ. Eventually, Gibson and Safinia found time to discuss "their mutual love of movies and what excites them about moviemaking".[3]

We started to talk about what to do next, but we specifically spent a lot of time on the action-chase genre of filmmaking. Those conversations essentially grew into the skeleton of ('Apocalypto'). We wanted to update the chase genre by, in fact, not updating it with technology or machinery but stripping it down to its most intense form, which is a man running for his life, and at the same time getting back to something that matters to him.

—Farhad Safinia[3]

Gibson said they wanted to "shake up the stale action-adventure genre", which he felt was dominated by CGI, stock stories and shallow characters and to create a footchase that would "feel like a car chase that just keeps turning the screws."[4]

Gibson and Safinia were also interested in portraying and exploring an ancient culture as it existed before the arrival of the Europeans. Considering both the Aztecs and the Maya, they eventually chose the Maya for their high sophistication and their eventual decline.

The Mayas were far more interesting to us. You can choose a civilization that is bloodthirsty, or you can show the Maya civilization that was so sophisticated with an immense knowledge of medicine, science, archaeology and engineering ... but also be able to illuminate the brutal undercurrent and ritual savagery that they practiced. It was a far more interesting world to explore why and what happened to them.

—Farhad Safinia[3]

The two researched ancient Maya history, reading both creation and destruction myths, including sacred texts such as the Popul Vuh.[5] In the audio commentary of the film's first DVD release, Safinia states that the old shaman's story (played by , a modern-day Maya storyteller[6]) was modified from an authentic Mesoamerican tale that was re-translated by Hilario Chi Canul, a professor of Maya, into the Yucatec Maya language for the film. He also served as a dialogue coach during production. As they researched the script, Safinia and Gibson traveled to Guatemala, Costa Rica and the Yucatán Peninsula to scout filming locations and visit Maya ruins.

Striving for a degree of historical accuracy, the filmmakers employed a consultant, Richard D. Hansen, a specialist in the Maya and assistant professor of archaeology at Idaho State University. As director of the Mirador Basin Project, he works to preserve a large swath of the Guatemalan rain forest and its Maya ruins. Gibson has said of Hansen's involvement: "Richard's enthusiasm for what he does is infectious. He was able to reassure us and make us feel secure that what we were writing had some authenticity as well as imagination."[5]

Other scholars of Mesoamerican history criticized the film for what they said were numerous inaccuracies.[7][8] A recent essay by Hansen on the film and a critical commentary on the criticisms of the film is now published.[9]

Gibson decided that all the dialogue would be in the Yucatec Maya language.[10] Gibson explains: "I think hearing a different language allows the audience to completely suspend their own reality and get drawn into the world of the film. And more importantly, this also puts the emphasis on the cinematic visuals, which are a kind of universal language of the heart."[5]

Costumes and makeup[]

The production team consisted of a large group of make-up artists and costume designers who worked to recreate the Maya look for the large cast. Led by Aldo Signoretti, the make-up artists daily applied the required tattoos, scarification, and earlobe extensions to all of the on-screen actors. According to advisor Richard D. Hansen, the choices in body make-up were based on both artistic license and fact: "I spent hours and hours going through the pottery and the images looking for tattoos. The scarification and tattooing was all researched, the inlaid jade teeth are in there, the ear spools are in there. There is a little doohickey that comes down from the ear through the nose into the septum – that was entirely their artistic innovation."[11] An example of attention to detail is the left arm tattoo of Seven, Jaguar Paw's wife, which is a horizontal band with two dots above – the Mayan symbol for the number seven.

Simon Atherton, an English armorer and weapon-maker who worked with Gibson on Braveheart, was hired to research and provide reconstructions of Maya weapons. Atherton also has a cameo as the cross-bearing Franciscan friar who appears on a Spanish ship at the end of the film.

Set design[]

Mel Gibson wanted Apocalypto to feature sets with buildings rather than relying on computer-generated images. Most of the step pyramids seen at the Maya city were models designed by Thomas E. Sanders. Sanders explained his approach: "We wanted to set up the Mayan world, but we were not trying to do a documentary. Visually, we wanted to go for what would have the most impact. Just as on Braveheart, you are treading the line of history and cinematography. Our job is to do a beautiful movie."[12]

However, while many of the architectural details of Maya cities are correct,[8] they are blended from different locations and eras,[8] a decision Farhad Safinia said was made for aesthetic reasons.[13] While Apocalypto is set during the terminal post-classic period of Maya civilization, the central pyramid of the film comes from the classic period, which ended in AD 900,[13] such as those found in the Postclassic sites of Muyil, Coba, and others in Quintana Roo, Mexico, where later cities are built around earlier pyramids. The temples are in the shape of those of Tikal in the central lowlands classic style but decorated with the Puuc style elements of the northwest Yucatán centuries later. Richard D. Hansen comments, "There was nothing in the post-classic period that would match the size and majesty of that pyramid in the film. But Gibson ... was trying to depict opulence, wealth, consumption of resources."[13] The mural in the arched walkway combined elements from the Maya codices, the Bonampak murals (over 700 years earlier than the film's setting), and the San Bartolo murals (some 1500 years earlier than the film's setting).[citation needed]

Filming[]

Gibson filmed Apocalypto mainly in Catemaco, San Andrés Tuxtla and Paso de Ovejas in the Mexican state of Veracruz. The waterfall scene was filmed at Eyipantla Falls, located in San Andrés Tuxtla. Other filming by second-unit crews took place in El Petén, Guatemala. The film was originally slated for an August 4, 2006, release, but Touchstone Pictures delayed the release date to December 8, 2006, due to heavy rains and two hurricanes interfering with filming in Mexico. Principal photography ended in July 2006.

Apocalypto was shot on high-definition digital video, using the Panavision Genesis camera.[14] During filming, Gibson and cinematographer Dean Semler employed Spydercam,[15] a suspended camera system allowing shooting from above. This equipment was used in a scene in which Jaguar Paw leaps off a waterfall.

We had a Spydercam shot from the top of [the] 150-foot [46 m] waterfall, looking over an actor's shoulder and then plunging over the edge—literally in the waterfall. I thought we'd be doing it on film, but we put the Genesis [camera] up there in a light-weight water housing. The temperatures were beyond 100 degrees [38 °C] at [the] top, and about 60 degrees [15 °C] at the bottom, with the water and the mist. We shot two fifty-minute tapes without any problems—though we [did get] water in there once and fogged up.[14]

A number of animals are featured in Apocalypto, including a Baird's tapir and a black jaguar. Animatronics or puppets were employed for the scenes injurious to animals.[16]

Soundtrack[]

The music to Apocalypto was composed by James Horner in his third collaboration with director Mel Gibson. The non-traditional score features a large array of exotic instruments and vocals by Pakistani singer Rahat Fateh Ali Khan.

Distribution and marketing[]

While Mel Gibson financed the film through his Icon Productions, Disney signed on to distribute Apocalypto for a fee in certain markets under the Touchstone Pictures label in North America, and Icon Film Distribution in the UK and Australia. The publicity for the film started with a December 2005 teaser trailer that was filmed before the start of principal photography and before Rudy Youngblood was cast as Jaguar Paw. As a joke, Gibson inserted a subliminal cameo of the bearded director in a plaid shirt with a cigarette hanging from his mouth posing next to a group of dust-covered Maya.[17] A clean-shaven Gibson also filmed a Mayan-language segment for the introduction of the 2006 Academy Awards in which he declined to host the ceremony. On September 23, 2006, Gibson pre-screened the unfinished film to two predominantly Native American audiences in the US state of Oklahoma, at the Riverwind Casino in Goldsby, owned by the Chickasaw Nation, and at Cameron University in Lawton.[18] He also did a pre-screening in Austin, Texas, on September 24 in conjunction with one of the film's stars, Rudy Youngblood.[19] In Los Angeles, Gibson screened Apocalypto and participated in a Q&A session for Latin Business Association[20] and for members of the Maya community.[21] Due to an enthusiastic response from exhibitors, Disney opened the film on more than 2,500 screens in the United States.[citation needed]

Themes[]

According to Mel Gibson, the Mayan setting of Apocalypto is "merely the backdrop" for a more universal story of exploring "civilizations and what undermines them".[22] The background to the events depicted is the terminal Postclassic period, immediately prior to the arrival of the Spanish, c. 1511, which the filmmakers researched before writing.

The corrosive forces of corruption are illustrated in specific scenes throughout the film. Excessive consumption can be seen in the extravagant lifestyle of the upper-class Maya, their vast wealth contrasted with the sickly, the extremely poor, and the enslaved. Environmental degradation is portrayed both in the exploitation of natural resources, such as the over-mining and farming of the land, but also through the treatment of people, families and entire tribes as resources to be harvested and sold into slavery. Political corruption is seen in the leaders' manipulation, the human sacrifice on a large scale, and the slave trade. The film shows slaves being forced to create the lime stucco cement that covered the temples, an act that some historians consider a major factor in the Maya decline. One calculation estimates that it would take five tons of jungle forestry to make one ton of quicklime. Historical consultant Richard D. Hansen explains, "I found one pyramid in El Mirador that would have required nearly 650 hectares (1,600 acres) of every single available tree just to cover one building with lime stucco... Epic construction was happening... creating devastation on a huge scale."[23]

The filmmakers intended this depiction of the Maya collapse to have relevance for contemporary society. The problems "faced by the Maya are extraordinarily similar to those faced today by our own civilization," co-writer Safinia stated during production, "especially when it comes to widespread environmental degradation, excessive consumption and political corruption".[5] Gibson has stated that the film is an attempt at illustrating the parallels between a great fallen empire of the past and the great empires of today, saying "People think that modern man is so enlightened, but we're susceptible to the same forces – and we are also capable of the same heroism and transcendence."[5][24] The film serves as a cultural critique – in Hansen's words, a "social statement" – sending the message that it is never a mistake to question our own assumptions about morality.[25]

However, Gibson has also stated that he wanted the film to be hopeful rather than entirely negative. Gibson has defined the title as "a new beginning or an unveiling – a revelation"; he says "Everything has a beginning and an end, and all civilizations have operated like that".[26] The Greek word (ἀποκαλύπτω, apokaluptō) is in fact a verb meaning "I uncover", "disclose", or "reveal".[27] Gibson has also said a theme of the film is the exploration of primal fears.[26]

Reception[]

Critical response[]

On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 66% based on 199 reviews, with an average rating of 6.34/10. The site's critical consensus reads: "Apocalypto is a brilliantly filmed, if mercilessly bloody, examination of a once great civilization."[28] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 68 out of 100, based on 37 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[29] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B+" on an A+ to F scale.[30]

Richard Roeper and guest critic Aisha Tyler on the television show Ebert & Roeper gave it "two thumbs up" rating.[31] Michael Medved gave Apocalypto four stars (out of four) calling the film "an adrenaline-drenched chase movie" and "a visceral visual experience."[32]

The film was released less than six months after Gibson's 2006 DUI incident, which garnered Gibson much negative publicity and magnified concerns some had over alleged antisemitism in his previous film, The Passion of the Christ.[33] Several key film critics alluded to the incident in their reviews of Apocalypto: In his positive review, The New York Times A. O. Scott commented: "say what you will about him – about his problem with booze or his problem with Jews – he is a serious filmmaker."[34] The Boston Globe's review came to a similar conclusion, noting that "Gibson may be a lunatic, but he's our lunatic, and while I wouldn't wish him behind the wheel of a car after happy hour or at a B'nai Brith function anytime, behind a camera is another matter."[35] In a negative review, Salon.com noted "People are curious about this movie because of what might be called extra-textual reasons, because its director is an erratic and charismatic Hollywood figure who would have totally marginalized himself by now if he didn't possess a crude gift for crafting violent pop entertainment."[36]

Apocalypto gained some passionate champions in the Hollywood community. Actor Robert Duvall called it "maybe the best movie I've seen in 25 years".[37][38] Director Quentin Tarantino said, "I think it's a masterpiece. It was perhaps the best film of that year. I think it was the best artistic film of that year."[39] Martin Scorsese, writing about the film, called it "a vision," adding, "Many pictures today don't go into troubling areas like this, the importance of violence in the perpetuation of what's known as civilization. I admire Apocalypto for its frankness, but also for the power and artistry of the filmmaking."[40] Actor Edward James Olmos said, "I was totally caught off guard. It's arguably the best movie I've seen in years. I was blown away."[20] In 2013, director Spike Lee put the film on his list of all-time essential films.[41]

On release in Mexico the film registered a wider number of viewers than Perfume and Rocky Balboa. It even displaced memorable Mexican premieres such as Titanic and Poseidon.[42] According to polls performed by the newspaper Reforma, 80% of polled Mexicans labeled the film as "very good" or "good".[42]

Awards[]

For his role as producer and director of the film, Mel Gibson was given the Trustee Award by the First Americans in the Arts organization. Gibson was also awarded the Latino Business Association's Chairman's Visionary Award for his work on Apocalypto on November 2, 2006, at the Beverly Hilton Hotel in Los Angeles. At the ceremony, Gibson said that the film was a "badge of honor for the Latino community."[43] Gibson also stated that Apocalypto would help dismiss the notion that "history only began with Europeans".[44]

Won[]

- Central Ohio Film Critics Association – COFCA Award for Best Cinematography (2007) – Dean Semler

- Dallas-Fort Worth Film Critics Association Awards – DFWFCA Award for Best Cinematography (2006) – Dean Semler

- First Americans in the Arts – FAITA Award for Outstanding Performance by an Actor (2007) – Rudy Youngblood

- First Americans in the Arts – FAITA Award for Outstanding Performance by an Actor (Supporting) (2007) – Morris Birdyellowhead

- Imagen Foundation – Imagen Award for Best Supporting Actor (2007) – Gerardo Taracena

- Imagen Foundation – Imagen Award for Best Supporting Actress (2007) – Dalia Hernandez

- Motion Picture Sound Editors, US – Golden Reel Award for Best Sound Editing for Music in a Feature Film (2007) – Dick Bernstein (music editor), Jim Henrikson (music editor)

- Phoenix Film Critics Society – PFCS Award for Best Cinematography (2006) – Dean Semler

Nominated[]

- Academy Awards 2007 - Best Makeup (2007) – Aldo Signoretti, Vittorio Sodano[45]

- Academy Awards 2007 for Best Sound Editing (2007) – Sean McCormack, Kami Asgar

- Academy Awards 2007, for Best Sound Mixing (2007) – Kevin O'Connell, Greg P. Russell, Fernando Cámara

- Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films, US – Saturn Award for Best Direction (2007) – Mel Gibson

- Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films, US – Saturn Award for Best International Film (2007)

- American Society of Cinematographers, US – ASC Award for Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography in Theatrical Releases (2007) – Dean Semler

- BAFTA Awards – BAFTA Film Award for Best Film not in the English Language (2007) – Mel Gibson, Bruce Davey

- Broadcast Film Critics Association Awards – BFCA Award for Best Foreign Language Film (2007)

- Chicago Film Critics Association Awards – CFCA Award for Best Foreign Language Film (2006)

- Golden Eagle Award[46] – Best Foreign Language Film (2007)

- Golden Globe Awards, US – Golden Globe for Best Foreign Language Film (2007)

- The Hollywood Reporter Key Art Awards – Key Art Award for Best Action-Adventure Poster (2006)

- Imagen Foundation – Imagen Award for Best Picture (2007)

- Motion Picture Sound Editors, US – Golden Reel Award for Best Sound Editing in a Feature Film: Dialogue and Automated Dialogue Replacement (2007) – Sean McCormack (supervising sound editor), Kami Asgar (supervising sound editor), Scott G.G. Haller (supervising dialogue editor), Jessica Gallavan (supervising ADR editor), Lisa J. Levine (supervising ADR editor), Linda Folk (supervising ADR editor)

- Online Film Critics Society Awards – OFCS Award for Best Cinematography (2007) – Dean Semler

- Satellite Awards – Satellite Award for Best Motion Picture, Foreign Language (2006)

- Saturn Awards, US - Saturn Award for Best International Film (2007)

- Saturn Awards, US - Saturn Award for Best Director (2007) - Mel Gibson

- St. Louis Gateway Film Critics Association Awards – Award for Best Foreign Language Film (2006)

Representation of the Maya[]

Many writers felt that Gibson's film was relatively accurate about the Maya, since it depicts the era of decline and division that followed the civilization's peak, collapse, re-settlement, and proto-historic societal conditions. One Mexican reporter, Juan E. Pardinas, wrote that "this historical interpretation bears some resemblances with reality .... Mel Gibson's characters are more similar to the Mayas of the Bonampak's murals than the ones that appear in the Mexican school textbooks."[47] "The first researchers tried to make a distinction between the 'peaceful' Maya and the 'brutal' cultures of central Mexico", David Stuart wrote in a 2003 article. "They even tried to say human sacrifice was rare among the Maya." But in carvings and mural paintings, Stuart said: "we have now found more and greater similarities between the Aztecs and Mayas."[48]

Richard D. Hansen, who was a historical consultant on the film, stated that the effect the film will have on Maya archaeology will be beneficial: "It is a wonderful opportunity to focus world attention on the ancient Maya and to realize the role they played in world history."[11] However, in an interview with The Washington Post, Hansen stated the film "give[s] the feeling they're a sadistic lot", and said, "I'm a little apprehensive about how the contemporary Maya will take it."[49]

Some observers were more cautious. William Booth of The Washington Post wrote that the film depicts the Maya as a "super-cruel, psycho-sadistic society on the skids, a ghoulscape engaged in widespread slavery, reckless sewage treatment and bad rave dancing, with a real lust for human blood",[49] despite of its historical accuracy. Gibson compared the savagery in the film to the Bush administration, telling British film magazine Hotdog, "The fear-mongering we depict in the film reminds me of President Bush and his guys."[50] Just prior to its release, Apocalypto was criticized by activists in Guatemala, including Lucio Yaxon, who charged that the trailer depicts Maya as savages.[51] In her review of the film, anthropologist Traci Ardren wrote that Apocalypto was biased because "no mention is made of the achievements in science and art, the profound spirituality and connection to agricultural cycles, or the engineering feats of Maya cities".[52] Apocalypto also sparked a strong condemnation from art history professor Julia Guernsey, a Mesoamerican specialist, who said, "I think it's despicable. It's offensive to Maya people. It's offensive to those of us who try to teach cultural sensitivity and alternative world views that might not match our own 21st century Western ones but are nonetheless valid."[53]

Human sacrifice[]

Apocalypto has been criticized for portraying a type of human sacrifice which was more typical of the Aztecs than of the Maya. Archaeologist Lisa Lucero said, "the classic Maya really didn't go in for mass sacrifice. That was the Aztecs."[13] Anthropology professor Karl Taube argued that, "We know the Aztecs did that level of killing. Their accounts speak of 20,000."[54] According to the film's technical advisor, the film was meant to describe the post-classic period of the Maya when fiercer influences like the Toltecs and Aztecs arrived. According to Hansen, "We know warfare was going on. The Postclassic center of Tulum is a walled city; these sites had to be in defensive positions. There was tremendous Aztec influence by this time. The Aztecs were clearly ruthless in their conquest and pursuit of sacrificial victims, a practice that spilled over into some of the Maya areas."[11] Anthropology professor Stephen Houston made the criticism that victims of sacrifice were more likely to be royalty and elites rather than common forest dwellers, as shown in Apocalypto.[54] Anthropology professor Karl Taube criticized the film's apparent depiction of widespread slavery, saying, "We have no evidence of large numbers of slaves."[54] Another disputed scene, when Jaguar Paw and the rest of the captives are used as target practice, was acknowledged by the filmmakers to be invented as a plot device for igniting the chase sequence.[13] Some anthropologists objected to the presence of a huge pit filled with rotting corpses near the fields of the Maya.[55] Hansen states that this is "conjecture", saying that "all [Gibson was] trying to do there is express the horror of it".[13]

The Washington Post reported that the famous Bonampak murals were digitally altered to show a warrior holding a dripping human heart, which is not present in the original.[56]

Ending[]

According to the DVD commentary track by Mel Gibson and Farhad Safinia, the ending of the film was meant to depict the first contact between the Spaniards and Mayas that took place in 1511 when Pedro de Alvarado arrived on the coast of the Yucatán and Guatemala, and also during the fourth voyage of Christopher Columbus in 1502.[57]

The thematic meaning of the arrival of the Europeans is a subject of disagreement. Traci Ardren wrote that the Spanish arrivals were Christian missionaries and that the film had a "blatantly colonial message that the Mayas needed saving because they were 'rotten at the core.'" According to Ardren, the Gibson film "replays, in glorious big-budget technicolor, an offensive and racist notion that Maya people were brutal to one another long before the arrival of Europeans and thus they deserved, in fact, they needed, rescue. This same idea was used for 500 years to justify the subjugation of Maya people."[52] On the other hand, David van Biema questions whether the Spaniards are portrayed as saviors of the Mayas since they are depicted ominously and Jaguar Paw decides to return to the woods.[58] This view is supported by the reference of the Oracle Girl to those who would "Scratch out the earth. Scratch you out. And end your world." However, recalling the opening quote to the film ("A great civilization is not conquered from without until it has destroyed itself from within"), professors David Stuart and Stephen Houston have written the implication is that Postclassic Mayans had become so corrupt that they were "a civilization ... that deserves to die."[49]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "Apocalypto". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved January 29, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Apocalypto (2006) - Box Office Mojo". www.boxofficemojo.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Nicole Sperling (December 15, 2006). "With help from a friend, Mel cut to the chase". The Washington Post.

- ^ Tim Padgett (March 27, 2006). "Apocalypto Now". Time. Archived from the original on May 12, 2006.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Apocalypto First Look". WildAboutMovies.

- ^ "Official Apocalypto DVD Website". Archived from the original on June 11, 2007.

- ^ ""Apocalypto" Tortures the Facts, Expert Says". National Geographic. October 28, 2010. Retrieved March 15, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c McGuire, Mark (December 12, 2006). "'Apocalypto' a pack of inaccuracies |". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved March 15, 2012.

- ^ Hansen, Richard D. "Relativism, Revisionism, Aboriginalism and Emic/Etic Truth: The Case Study of Apocalypto." Book chapter in: "The Ethics of Anthropology and Amerindian Research", edited by Richard J. Chacon and Ruben G. Mendoza, pp. 147–190. Springer Press, New York, Dordrecht, Heidelberg, London 2012

- ^ "Prophets-Apoc".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Mel Gibson's Maya". Archaeology. 60 (1). January–February 2007.

- ^ Susan King (December 7, 2006). "Apocalypto's look mixes fact and fiction". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Global Heritage Fund". Archived from the original on November 2, 2007.

About 25 members of the Maya community in Los Angeles were invited to an advance screening of Gibson's film last week. Two of those who attended came away impressed, but added that they too wished Gibson had shown more of the Maya civilization. 'It was a great action film that kept me on the edge of my seat,' said Sara Zapata Mijares, president and founder of Federacion de Clubes Yucatecos-USA. 'I think it should have had a little bit more of the culture', such as the pyramids. 'It could have shown a little more why these buildings were built.'

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Dion Beebe, Dean Semler, Tom Sigel, and others on Digital Cinematography". June 16, 2006.

- ^ "spydercam: Info – Work History". Archived from the original on June 2, 2004.

- ^ "The First Tapir Movie Star?". Archived from the original on February 15, 2012.

- ^ Caryn James (December 22, 2005). "Suddenly, Next Summer". The New York Times.

- ^ "Gibson takes 'Apocalypto' to Oklahoma". Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 28, 2006.

- ^ "Mel campaigns for new movie, against war in Iraq". Reuters. September 24, 2006. Archived from the original on September 8, 2006.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Robert W. Welkos (November 13, 2006). "Gibson dives in". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Robert W. Welkos (December 9, 2006). "In Apocalypto, fact and fiction play hide and seek". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Reed Johnson (October 29, 2005). "Mel Gibson's latest passion: Maya culture". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Production Notes: The Heart of Apocalypto".

- ^ "Mel Gibson criticizes Iraq war at film fest – Troubled filmmaker draws parallels to collapsing Mayan civilization". Associated Press. September 25, 2006.

- ^ "Gibson film angers Mayan groups". BBC. December 8, 2006.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Lost Kingdom: Mel Gibson's Apocalypto". ABC Primetime. November 22, 2006.

- ^ "Making Yucatec Maya "cool again"". Language Log. November 7, 2005.

- ^ Apocalypto, Rotten Tomatoes, retrieved July 19, 2019

- ^ "Apocalypto Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ "Find CinemaScore" (Type "Apocalypto" in the search box). CinemaScore. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ Ebert & Roeper air date December 10, 2006

- ^ Medved, Michael, Apocalypto (Microsoft Word) (review)[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Gibson takes first starring role in six years", The Guardian, UK, April 29, 2008, retrieved January 14, 2011

- ^ Scott, AO (December 8, 2006), "The Passion of the Maya", The New York Times, retrieved January 14, 2011

- ^ Ty Burr, Mel Gibson luxuriates in violence in 'Apocalypto' The Boston Globe, December 8, 2006, Retrieved January 14, 2011.

- ^ Andrew O'Hehir, "Apocalypto" Salon.com, December 8, 2006, Retrieved January 14, 2011.

- ^ "Robert Duvall interview". Premiere. March 2007. Archived from the original on December 11, 2007.

- ^ David Carr (February 12, 2007). "Apocalypto's Biggest Fan". The New York Times.

- ^ "Interview with Quentin Tarantino", FilmInk, August 2007.

- ^ "The Naked Prey (1966 [sic]) and Apocalypto (2006)". DIRECTV.

- ^ "Read Spike Lee's 'Essential List of Films for Filmmakers" Vulture.com, Jesse David Fox, July 26, 2013

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Califican con 7.6 a Apocalypto". Reforma. January 30, 2007.

- ^ "Gibson honored by Latino business group". USA Today. November 3, 2006. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ^ "TodoExito.com – Events". Archived from the original on October 29, 2007. Retrieved May 26, 2007.

- ^ "The 79th Academy Awards (2007) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- ^ Золотой Орел 2007 [Golden Eagle 2007] (in Russian). Ruskino.ru. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- ^ "Nacionalismo de piel delgada". Reforma. February 4, 2007.

Translation from the original in Spanish: "La mala noticia es que esta interpretación histórica tiene alguna dosis de realidad... Los personajes de Mel Gibson se parecen más a los mayas de los murales de Bonampak que a los que aparecen en los libros de la SEP"

- ^ Stevenson, Mark (January 24, 2005). "A fresh look at tales of human sacrifice – Technology & science – Science – NBC News". NBC News. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Culture Shocker". The Washington Post. December 9, 2006.

- ^ "Mel Gibson Compares President Bush to Barbaric Mayans". Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ "Gibson film angers Mayan groups". BBC. December 8, 2006.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Is "Apocalypto" Pornography?". Archaeology. December 5, 2006.

- ^ Chris Garcia (December 6, 2006). "Apocalypto is an insult to Maya culture, one expert says". American-Statesman.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c William Booth (December 9, 2006). "Culture Shocker". The Washington Post.

- ^ Mark McGuire (December 12, 2006). "Apocalypto a pack of inaccuracies". San Diego Union Tribune.

- ^ Culture Shocker, The Washington Post, December 9, 2009

- ^ "The Fourth Voyage of Christopher Columbus (1502)". Athena Review. 2 (1). Archived from the original on May 27, 2008. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ van Biema, David (December 14, 2006). "What Has Mel Gibson Got Against the Church?". Time. Archived from the original on January 4, 2008.

External links[]

- 2006 films

- 2000s action adventure films

- 2000s historical adventure films

- 2006 action films

- American action adventure films

- American adventure drama films

- American epic films

- American films

- American historical adventure films

- American survival films

- Films directed by Mel Gibson

- Films produced by Bruce Davey

- Films produced by Mel Gibson

- Films scored by James Horner

- Films set in Guatemala

- Films set in Mesoamerica

- Films set in pre-Columbian America

- Films set in the 1500s

- Films shot in Mexico

- Films with screenplays by Farhad Safinia

- Films with screenplays by Mel Gibson

- Icon Productions films

- Indigenous cinema in Latin America

- Indigenous films

- Jungle adventure films

- Mayan-language films

- Scanbox Entertainment films

- Touchstone Pictures films

- Yucatec Maya language