The Passion of the Christ

| The Passion of the Christ | |

|---|---|

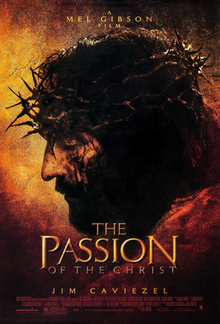

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Mel Gibson |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | The Passion in the New Testament of the Bible and The Dolorous Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ by Anne Catherine Emmerich |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Caleb Deschanel |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | John Debney |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Icon Productions |

Release date |

|

Running time | 127 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Languages | |

| Budget | $30 million[2] |

| Box office | $612 million[2] |

The Passion of the Christ[3] is a 2004 American biblical drama film produced, co-written and directed by Mel Gibson and starring Jim Caviezel as Jesus of Nazareth, Maia Morgenstern as the Virgin Mary, and Monica Bellucci as Mary Magdalene. It depicts the Passion of Jesus largely according to the gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. It also draws on pious accounts such as the Friday of Sorrows, along with other devotional writings, such as the reputed visions attributed to Anne Catherine Emmerich.[4][5][6][7]

The film primarily covers the final 12 hours before Jesus Christ's death, consisting of the Passion, hence the title of the film. It begins with the Agony in the Garden in the Garden of Olives (or Gethsemane), continues with the betrayal of Judas Iscariot, the brutal Scourging at the Pillar, the suffering of Mary as prophesied by Simeon, and the crucifixion and death of Jesus, and ends with a brief depiction of his resurrection. However, the film also has flashbacks to particular moments in Jesus' life, some of which are biblically based, such as The Last Supper and The Sermon on the Mount, and others that are artistic license, as when Mary comforts Jesus and when Jesus crafts a table.

The film was mostly shot in Italy.[8] The dialogue is entirely in Hebrew, Latin, and reconstructed Aramaic. Although Gibson was initially against it, the film is subtitled.

The film has been controversial and received largely polarized reviews, with some critics calling the film a religious classic while others found the extreme violence distracting and excessive. The film grossed over $612 million worldwide[9] and became the fifth highest grossing film of 2004 internationally at the end of its theatrical run.[2] It is the highest-grossing (inflation unadjusted) Christian film of all time.[10] It received three nominations at the 77th Academy Awards in 2005, for Best Makeup, Best Cinematography, and Best Original Score.[11]

Plot[]

In Gethsemane, Jesus Christ prays in the night while his disciples Peter, James, and John sleep. Satan appears to Jesus in a hooded ghost-like androgynous, albino form, and tempts him. Jesus' sweat turns into blood and drips to the ground while a serpent emerges from Satan's guise. Hearing his disciples, he rebukes Satan by crushing the snake's head.

Bribed disciple Judas Iscariot leads a group of temple guards to the forest and betrays Jesus' identity. As the guards arrest Jesus, a fight erupts wherein Peter draws his dagger and slashes the ear of Malchus, one of the guards and a servant of the high priest Caiaphas. Jesus heals Malchus' injury while reprimanding Peter. As the disciples flee, the guards secure Jesus, and beat him during the journey to the Sanhedrin.

John informs Mary, mother of Jesus and Mary Magdalene of the arrest, while Peter follows Jesus and his captors. Magdalene begs a passing Roman patrol to intervene but a temple guard claims she is unbalanced. Caiaphas holds trial over the objection of some priests who are expelled from the court, during which false accusations and witnesses are brought against Jesus. When Caiaphas asks him whether he is the Son of God, Jesus replies, "I am". Caiaphas angrily tears his robes and Jesus is condemned to death for blasphemy. Peter is confronted by the surrounding mob for following Jesus. After cursing at the mob during the third denial, Peter flees when he recalls Jesus's forewarning of his defense. A guilt-ridden Judas attempts to return the money he was paid in order to have Jesus freed, but is refused by the priests. Tormented by demons , he runs away from the city and hangs himself.

Caiaphas brings Jesus before Pontius Pilate to be condemned to death, but at the urging of Pilate's wife Claudia, who knows Jesus is a man of God, and after questioning Jesus and finding no fault, Pilate transfers him to the court of Herod Antipas, as Jesus is from Antipas' ruling town of Nazareth, Galilee. After Jesus is found not guilty and returned, Pilate offers the crowd the choice of chastising Jesus or releasing him. He attempts to have Jesus freed by the peoples' choice between Jesus and violent criminal Barabbas. The crowd demands Barabbas be freed and Jesus crucified. Attempting to appease the crowd, Pilate orders that Jesus simply be flogged. The Roman guards scourge, abuse, and mock Jesus, before taking him to a barn where they place a crown of thorns on his head and tease him saying “Hail, king of the Jews”. A bruised Jesus is presented before Pilate, but Caiaphas, with the crowds' verbal backing, continues demanding that Jesus be crucified and Barabbas released. Pilate reluctantly orders Jesus' crucifixion. Satan observes Jesus' sufferings with sadistic pleasure.

As Jesus carries a heavy wooden cross along the Via Dolorosa to Calvary, a woman avoids the escort of soldiers and requests that Jesus wipe his face with her cloth, to which he consents. She offers Jesus a pot of water to drink but the guard hurls it away and dispels her. During the journey to Golgotha, Jesus is beaten by the guards until the unwilling Simon of Cyrene is forced into carrying the cross with him. At the end of their journey, with his mother Mary, Mary Magdalene, and others witnessing, Jesus is crucified.

Hanging from the cross, Jesus prays to God asking forgiveness for his tormentors, and provides salvation to a criminal crucified beside him, for his strong faith and repentance. Succumbing to impending death, Jesus surrenders his spirit to the Father and dies. A single droplet of rain falls from the sky to the ground, triggering an earthquake which destroys the temple and rips the veil covering the Holy of Holies in two. Satan screams in defeat from the depths of Hell. Jesus' body is taken down from the cross and entombed. Jesus rises from the dead and exits the tomb resurrected, with wound holes visible on his palms.

Cast[]

- Jim Caviezel as Jesus Christ

- Maia Morgenstern as Mary, the mother of Jesus

- Christo Jivkov as John

- Francesco De Vito as Peter

- Monica Bellucci as Mary Magdalene

- Mattia Sbragia as Caiaphas

- Toni Bertorelli as Annas ben Seth

- Luca Lionello as Judas Iscariot

- Hristo Naumov Shopov as Pontius Pilate

- Claudia Gerini as Claudia Procles

- Fabio Sartor as Abenader

- Giacinto Ferro as Joseph of Arimathea

- Olek Mincer as Nicodemus

- Sheila Mokhtari as Woman in audience

- Sergio Rubini as Dismas

- Roberto Bestazoni as Malchus

- Francesco Cabras as Gesmas

- Giovanni Capalbo as Cassius

- Rosalinda Celentano as Satan

- Emilio De Marchi as Scornful Roman

- Lello Giulivo as Brutish Roman

- Abel Jafry as 2nd Temple officer

- Jarreth Merz as Simon of Cyrene

- Rossella Vetrano as Veronica

- Matt Patresi as Janus

- Roberto Visconti as Scornful Roman

- Luca De Dominicis as Herod Ántipas

- Chokri Ben Zagden as James

- Sabrina Impacciatore as St. Veronica

- Pietro Sarubbi as Barabbas

- Ted Rusoff as Chief Elder

Themes[]

In The Passion: Photography from the Movie "The Passion of the Christ", director Mel Gibson says, "This is a movie about Love, Hope, Faith and forgiveness. Jesus died for all mankind, suffered for all of us. It's time to get back to that basic message. The world has gone nuts. We could all use a little more Love, Faith, Hope and forgiveness."

Source material[]

New Testament[]

According to Mel Gibson, the primary source material for The Passion of the Christ is the four canonical Gospel narratives of Christ's passion. The film includes a trial of Jesus at Herod's court, which is only found in the Gospel of Luke. Many of the utterances from Jesus in the film cannot be directly sourced to the Gospel and are part of a wider Christian narrative. The film also draws from other parts of the New Testament. One line spoken by Jesus in the film, "I make all things new", is found in the Book of Revelation, Chapter 21, verse 5.[12]

Old Testament[]

The film also refers to the Old Testament. The film begins with an epigraph from the Fourth Song of the Suffering Servant from Isaiah.[13] In the opening scene set in the Garden of Gethsemane, Jesus crushes a serpent's head in direct visual allusion to Genesis 3:15.[14] Throughout the film, Jesus quotes from the Psalms, beyond the instances recorded in the New Testament.

Traditional iconography and stories[]

Many of the depictions in the film deliberately mirror traditional representations of the Passion in art. For example, the 14 Stations of the Cross are central to the depiction of the Via Dolorosa in The Passion of the Christ. All the stations are portrayed except for the eighth station (Jesus meets the women of Jerusalem, a deleted scene on the DVD) and the fourteenth station (Jesus is laid in the tomb). Gibson was inspired by the representation of Jesus on the Shroud of Turin.[15]

At the suggestion of actress Maia Morgenstern, the Passover Seder is quoted early in the film. Mary asks "Why is this night different from other nights?", and Mary Magdalene replies with the traditional response: "Because once we were slaves, and we are slaves no longer."[16]

The conflation of Mary Magdalene with the adulteress saved from stoning by Jesus has some precedent in tradition, and according to the director was done for dramatic reasons. The names of some characters in the film are traditional and extra-Scriptural, such as the thieves crucified alongside the Christ, Dismas and Gesmas (also Gestas).

Catholic devotional writings[]

Screenwriters Gibson and Benedict Fitzgerald said that they read many accounts of Christ's Passion for inspiration, including the devotional writings of Roman Catholic mystics. A principal source is The Dolorous Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ[17] the visions of Anne Catherine Emmerich (1774–1824), as written by the poet Clemens Brentano.[5][6][7] A careful reading of Emmerich's book shows the film's high level of dependence on it.[5][6][18]

However, Brentano's attribution of the book The Dolorous Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ to Emmerich has been subject to dispute, with allegations that Brentano wrote much of the book himself; a Vatican investigation concluding that: "It is absolutely not certain that she ever wrote this".[19][20][21] In his review of the film in the Catholic publication America, Jesuit priest John O'Malley used the terms "devout fiction" and "well-intentioned fraud" to refer to the writings of Clemens Brentano.[4][19]

Production[]

Script and language[]

Gibson originally announced that he would use two old languages without subtitles and rely on "filmic storytelling". Because the story of the Passion is so well known, Gibson felt the need to avoid vernacular languages in order to surprise audiences: "I think it's almost counterproductive to say some of these things in a modern language. It makes you want to stand up and shout out the next line, like when you hear 'To be or not to be' and you instinctively say to yourself, 'That is the question.'"[22] The script was written in English by Gibson and Benedict Fitzgerald, then translated by William Fulco, S.J., a professor at Loyola Marymount University, into Latin and reconstructed Aramaic. Gibson chose to use Latin instead of Koine Greek, which was the lingua franca of that particular part of the Roman Empire at the time, since there is no source for the Koine Greek spoken in that region. The street Greek spoken in the ancient Levant region of Jesus' day is not the exact Greek language used in the Bible.[23] Fulco sometimes incorporated deliberate errors in pronunciations and word endings when the characters were speaking a language unfamiliar to them, and some of the crude language used by the Roman soldiers was not translated in the subtitles.[24]

Filming[]

The film was produced independently and shot in Italy at Cinecittà Studios in Rome, and on location in the city of Matera and the ghost town of Craco, both in the Basilicata region. The estimated US$30 million production cost, plus an additional estimated $15 million in marketing costs, were fully borne by Gibson and his company Icon Productions. According to the DVD special feature, Martin Scorsese had recently finished his film Gangs of New York, from which Gibson and his production designers constructed part of their set using Scorsese's set. This saved Gibson a lot of time and money.

Gibson's film was released on Ash Wednesday, February 25, 2004. Icon Entertainment distributed the theatrical version of the film, and 20th Century Fox distributed the VHS/DVD/Blu-ray version of the film.

Gibson consulted several theological advisers during filming, including Fr. Jonathan Morris. A local priest visited the set daily to provide counsel, Confession, and Holy Communion to Jim Caviezel, and Masses were celebrated for cast and crew in several locations.[25] During filming, assistant director Jan Michelini was struck twice by lightning. Minutes later, Caviezel also was struck.[26][27][28]

Music[]

Three albums were released with Mel Gibson's co-operation: (1) the film soundtrack of John Debney's original orchestral score conducted by Nick Ingman; (2) The Passion of the Christ: Songs, by producers Mark Joseph and Tim Cook, with original compositions by various artists, and (3) Songs Inspired by The Passion of the Christ. The first two albums each received a 2005 Dove award, and the soundtrack received an Academy Award nomination of Best Original Music Score.

A preliminary score was composed and recorded by Lisa Gerrard and Patrick Cassidy, but was incomplete at film's release. Jack Lenz was the primary musical researcher and one of the composers;[29] several clips of his compositions have been posted online.[30]

Title change[]

Although Mel Gibson wanted to call his film The Passion, on October 16, 2003, his spokesman announced that the title used in the United States would be The Passion of Christ because Miramax Films had already registered the title The Passion with the MPAA for the 1987 novel by Jeanette Winterson.[31] Later, the title was changed again to The Passion of the Christ for all markets.

Distribution and marketing[]

Gibson began production on his film without securing outside funding or distribution. In 2002, he explained why he could not get backing from the Hollywood studios: "This is a film about something that nobody wants to touch, shot in two dead languages."[32] Gibson and his company Icon Productions provided the film's sole backing, spending about $30 million on production costs and an estimated $15 million on marketing.[33] After early accusations of antisemitism, it became difficult for Gibson to find an American distribution company. 20th Century Fox initially had a first-look deal with Icon but decided to pass on the film in response to public protests.[34] In order to avoid the spectacle of other studios turning down the film and to avoid subjecting the distributor to the same intense public criticism he had received, Gibson decided to distribute the film in the United States himself, with the aid of Newmarket Films.[35]

Gibson departed from the usual film marketing formula. He employed a small-scale television advertising campaign with no press junkets.[36] Similar to marketing campaigns for earlier biblical films like The King of Kings, The Passion of the Christ was heavily promoted by many church groups, both within their organizations and to the public. Typical licensed merchandise like posters, T-shirts, coffee mugs and jewelry was sold through retailers and websites.[37] The United Methodist Church stated that many of its members, like other Christians, felt that the film was a good way to evangelize non-believers.[38] As a result, many congregations planned to be at the theaters, and some set up tables to answer questions and share prayers.[38] Rev. John Tanner, pastor of Cove United Methodist Church in Hampton Cove, Alabama, said: "They feel the film presents a unique opportunity to share Christianity in a way today's public can identify with."[38] The Seventh-day Adventist Church also expressed a similar endorsement of the picture.[39]

Evangelical support[]

The Passion of the Christ received enthusiastic support from the American evangelical community.[40] Before the film's release, Gibson actively reached out to evangelical leaders seeking their support and feedback.[41] With their help, Gibson organized and attended a series of pre-release screenings for evangelical audiences and discussed the making of the film and his personal faith. In June 2003 he screened the film for 800 pastors attending a leadership conference at New Life Church, pastored by Ted Haggard, then president of the National Association of Evangelicals.[42] Gibson gave similar showings at Joel Osteen's Lakewood Church, Greg Laurie's Harvest Christian Fellowship, and to 3,600 pastors at a conference at Rick Warren's Saddleback Church in Lake Forest.[43] From the summer of 2003 to the film's release in February 2004, portions or rough cuts of the film were shown to over eighty audiences—many of which were evangelical audiences.[44] The film additionally received public endorsements from evangelical leaders, including Rick Warren, Billy Graham, Robert Schuller, Darrell Bock, Christianity Today editor David Neff, Pat Robertson, Lee Strobel, Jerry Falwell, Max Lucado, Tim LaHaye and Chuck Colson.[44][45]

Release[]

Box office and theatrical run[]

The Passion of the Christ opened in the United States on February 25, 2004 (Ash Wednesday, the beginning of Lent). It earned $83,848,082 from 4,793 screens at 3,043 theaters in its opening weekend and a total of $125,185,971 since its Wednesday opening, ranking it fourth overall in domestic opening weekend earnings for 2004 as well as the biggest weekend debut for a February release (until Fifty Shades of Grey was released). It went on to earn $370,782,930 overall in the United States,[2] and remains the highest grossing R-rated film in the domestic market (U.S. & Canada).[46][47][48][49][50] The film sold an estimated 59,625,500 tickets in the US in its initial theatrical run.[51]

In the Philippines, a majority-Catholic country, the film was released on March 31, 2004,[52][53] rated PG-13 by the Movie and Television Review and Classification Board (MTRCB)[54] and endorsed by the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines (CBCP).[55]

In Malaysia, government censors initially banned it completely, but after Christian leaders protested, the restriction was lifted, but only for Christian audiences, allowing them to view the film in specially designated theaters.[56] In Israel, the film was not banned. However, it never received theatrical distribution because no Israeli distributor would market it.[57]

Despite the many controversies and refusals by some governments to allow the film to be viewed in wide release, The Passion of the Christ earned $612,054,428 worldwide.[2] The film was also a relative success in certain countries with large Muslim populations,[58] such as in Egypt, where it ranked 20th overall in its box office numbers for 2004.[59] The film was the highest grossing non-English-language film of all time[60] until 2017, when it was surpassed by Wolf Warrior 2.[61]

Re-edited theatrical release on March 11, 2005[]

The Passion Recut was released in theaters on March 11, 2005, with five minutes of the most explicit violence deleted. Gibson explained his reasoning for this re-edited version:

After the initial run in movie theaters, I received numerous letters from people all across the country. Many told me they wanted to share the experience with loved ones but were concerned that the harsher images of the film would be too intense for them to bear. In light of this I decided to re-edit The Passion of the Christ.[62]

Despite the re-editing, the Motion Picture Association of America still deemed The Passion Recut too violent for PG-13, so its distributor released it as unrated.[62] The shortened film showed for three weeks in 960 theaters for a box office total of $567,692, minuscule compared to the $612,054,428 of The Passion.[63]

Home media[]

On August 31, 2004, the film was released on VHS and DVD in North America by 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment, which initially passed on theatrical distribution.[citation needed] As with the original theatrical release, the film's release on home video formats proved to be very popular. Early estimates indicated that over 2.4 million copies of the film were sold by 3 pm,[64] with a total of 4.1 million copies on its first day of sale.[65] The film was available on DVD with English and Spanish subtitles and on VHS tape with English subtitles. The film was released on Blu-ray in North America as a two-disc Definitive Edition set on February 17, 2009.[66] It was also released on Blu-ray in Australia a week before Easter.

Although the original DVD release sold well, it contained no bonus features other than a trailer, which provoked speculation about how many buyers would wait for a special edition to be released.[64] On January 30, 2007, a two-disc Definitive Edition was released in the North American markets, and March 26 elsewhere. It contains several documentaries, soundtrack commentaries, deleted scenes, outtakes, the 2005 unrated version, and the original 2004 theatrical version.

The British version of the two-disc DVD contains two additional deleted scenes. In the first, Jesus meets the women of Jerusalem (at the eighth station of the cross) and falls to the ground as the women wail around him, and Simon of Cyrene attempts to hold up the cross and help up Jesus simultaneously. Afterwards, while both are holding up the cross, Jesus says to the women weeping for him, "Do not weep for me, but for yourselves and for your children". In the second, Pilate washes his hands, turns to Caiaphas, and says: "Look you to it" (i.e., the Pharisees wish to have Jesus crucified). Pilate then turns to Abanader and says: "Do as they wish". The scene next shows Pilate calling to his servant, who is carrying a wooden board on which Pilate writes, "Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews", in Latin and Hebrew. He then holds the board above his head in full view of Caiaphas, who after reading it challenges Pilate on its content. Pilate replies angrily to Caiaphas in non-subtitled Hebrew. The disc contains only two deleted scenes in total. No other scenes from the movie are shown on disc 2.[67]

On February 7, 2017, 20th Century Fox re-released the film on Blu-ray and DVD featuring both cuts, with the theatrical version being dubbed in English and Spanish;[68] this marks the first time the film has ever been dubbed in another language.

Television broadcast[]

On April 17, 2011 (Palm Sunday), Trinity Broadcasting Network (TBN) presented the film at 7:30 pm ET/PT, with multiple showings scheduled. The network has continued to air the film throughout the year, and particularly around Easter.[69]

On March 29, 2013 (Good Friday), as a part of their special Holy Week programming, TV5 presented the Filipino-dubbed version of the film at 2:00 pm (PST, UTC+8) in the Philippines. Its total broadcast ran for two hours, but excluding the advertisements, it would only run up for approximately one hour instead of its full run time of two hours and six minutes. It ended at 4:00 pm. It has been rated SPG by the Movie and Television Review and Classification Board (MTRCB) for themes, language and violence with some scenes censored for television. TV5 is the first broadcast network outside of the United States and dubbed the Vernacular Hebrew and Latin language to Filipino (through translating its supplied English subtitles).

Reception[]

Critical response[]

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 49% based on 278 reviews, with an average rating of 5.91/10. The website's critical consensus reads: "Director Mel Gibson's zeal is unmistakable, but The Passion of the Christ will leave many viewers emotionally drained rather than spiritually uplifted."[70] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average of 47 out of 100, based on 44 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[71] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film a rare "A+" grade.[72]

In a positive review for Time, its critic Richard Corliss called The Passion of the Christ "a serious, handsome, excruciating film that radiates total commitment."[71] New York Press film critic Armond White praised Gibson's direction, comparing him to Carl Theodor Dreyer in how he transformed art into spirituality.[73] White also noted that it was odd to see Director Mel Gibson offer audiences "an intellectual challenge" with the film.[74] Roger Ebert from the Chicago Sun-Times gave the movie four out of four stars, calling it "the most violent film I have ever seen" as well as reflecting on how it struck him, a former altar boy: "What Gibson has provided for me, for the first time in my life, is a visceral idea of what the Passion consisted of. That his film is superficial in terms of the surrounding message—that we get only a few passing references to the teachings of Jesus—is, I suppose, not the point. This is not a sermon or a homily, but a visualization of the central event in the Christian religion. Take it or leave it."[75]

In a negative review, Slate magazine's David Edelstein called it "a two-hour-and-six-minute snuff movie",[76] and Jami Bernard of the New York Daily News felt it was "the most virulently anti-Semitic movie made since the German propaganda films of World War II".[77] Writing for the Dallas Observer, Robert Wilonsky stated that he found the movie "too turgid to awe the nonbelievers, too zealous to inspire and often too silly to take seriously, with its demonic hallucinations that look like escapees from a David Lynch film; I swear I couldn't find the devil carrying around a hairy-backed midget anywhere in the text I read."[71]

The June 2006 issue of Entertainment Weekly named The Passion of the Christ the most controversial film of all time, followed by Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange (1971).[78] In 2010, Time listed it as one of the most "ridiculously violent" films of all time.[79]

Independent promotion and discussion[]

A number of independent websites, such as MyLifeAfter.com and Passion-Movie.com, were launched to promote the film and its message and to allow people to discuss the film's effect on their lives. Documentaries such as Changed Lives: Miracles of the Passion chronicled stories of miraculous savings, forgiveness, newfound faith, and the story of a man who confessed to murdering his girlfriend after authorities determined her death was due to suicide.[80] Another documentary, Impact: The Passion of the Christ, chronicled the popular response of the film in the United States, India, and Japan and examined the claims of antisemitism against Mel Gibson and the film.

Accolades[]

Wins[]

- National Board of Review – Freedom of Expression (tie)

- People's Choice Awards – Favorite Motion Picture Drama

- Satellite Awards – Best Director

- Ethnic Multicultural Media Academy (EMMA Awards) – Best Film Actress – Maia Morgenstern

- Motion Picture Sound Editors (Golden Reel Awards) – Best Sound Editing in a Feature Film – Music – Michael T. Ryan

- American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers – ASCAP Henry Mancini Award – John Debney[citation needed]

- Hollywood Film Festival, US – Hollywood Producer of the Year – Mel Gibson[81][82]

- GMA Dove Award, The Passion of the Christ Original Motion Picture Soundtrack, Instrumental Album of the Year

- Golden Eagle Award – Best Foreign Language Film[83]

Nominations[]

- Academy Awards

- Best Cinematography – Caleb Deschanel

- Best Makeup – Keith Vanderlaan, Christien Tinsley

- Best Original Score – John Debney

- American Society of Cinematographers – Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography in Theatrical Releases – Caleb Deschanel

- Broadcast Film Critics Association Awards – Best Popular Movie

- Irish Film and Television Awards – Jameson People's Choice Award for Best International Film

- MTV Movie Awards – Best Male Performance – Jim Caviezel

Other honors[]

The film was nominated in the following categories for American Film Institute recognition:

- 2006: AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers – Nominated[84]

- 2008: AFI's 10 Top 10 – Nominated Epic Film[85]

Rewritten on the Podcast "Never Seen It with Kyle Ayers" by comedian Ahri Findling[86]

Controversies[]

Questions of historical and biblical accuracy[]

Despite criticisms that Gibson deliberately added material to the historical accounts of first-century Judea and biblical accounts of Christ's crucifixion, some scholars defend the film as not being primarily concerned with historical accuracy. Biblical scholar Mark Goodacre protested that he could not find one documented example of Gibson explicitly claiming the film to be historically accurate.[87][88] Gibson has been quoted as saying: "I think that my first duty is to be as faithful as possible in telling the story so that it doesn't contradict the Scriptures. Now, so long as it didn't do that, I felt that I had a pretty wide berth for artistic interpretation, and to fill in some of the spaces with logic, with imagination, with various other readings."[89] One such example is a scene in Judas Iscariot being tormented by demons in the form of children. Another scene shows Satan is seen carrying a demonic baby during Christ's flogging, construed as a perversion of traditional depictions of the Madonna and Child, and also as a representation of Satan and the Antichrist. Gibson's description:

It's evil distorting what's good. What is more tender and beautiful than a mother and a child? So the Devil takes that and distorts it just a little bit. Instead of a normal mother and child you have an androgynous figure holding a 40-year-old 'baby' with hair on his back. It is weird, it is shocking, it's almost too much—just like turning Jesus over to continue scourging him on his chest is shocking and almost too much, which is the exact moment when this appearance of the Devil and the baby takes place.[90]

When asked about the film's faithfulness to the account given in the New Testament, Father Augustine Di Noia of the Vatican's Doctrinal Congregation replied: "Mel Gibson's film is not a documentary... but remains faithful to the fundamental structure common to all four accounts of the Gospels" and "Mel Gibson's film is entirely faithful to the New Testament".[91]

Disputed papal endorsement[]

On December 5, 2003, Passion of the Christ co-producer Stephen McEveety gave the film to Archbishop Stanisław Dziwisz, the pope's secretary.[92] John Paul II watched the film in his private apartment with Archbishop Dziwisz on Friday and Saturday, December 5 and 6, and later met with McEveety.[93] Jan Michelini, an Italian and the movie's assistant director, was also there when Dziwisz and McEveety met.[94][95] On December 16, Variety reported the pope, a movie buff, had watched a rough version of the film.[96] On December 17, Wall Street Journal columnist Peggy Noonan reported John Paul II had said "It is as it was", sourcing McEveety, who said he heard it from Dziwisz.[3] Noonan had emailed Joaquín Navarro-Valls, the head of the Vatican's press office, for confirmation before writing her December 17 column, surprised that the "famously close-mouthed" Navarro-Valls had approved the use of the "It is as it was" quote, and his emailed response stated he had no other comment at that time.[97] National Catholic Reporter journalist John L. Allen Jr., published a similar account on the same day, quoting an unnamed senior Vatican official.[93] On December 18, Reuters[97] and the Associated Press independently confirmed the story, citing Vatican sources.[98]

On December 24, an anonymous Vatican official told Catholic News Service "There was no declaration, no judgment from the pope." On January 9, Allen defended his earlier reporting, saying that his official source was adamant about the veracity of the original story.[93] On January 18, columnist Frank Rich for The New York Times wrote that the statement was "being exploited by the Gibson camp", and that when he asked Michelini about the meeting, Michelini said Dziwisz had reported the pope's words as "It is as it was", and said the pope also called the film "incredibile", an Italian word Michelini translated as "amazing".[94] The next day Archbishop Dziwisz told CNS, "The Holy Father told no one his opinion of this film."[95] This denial resulted in a round of commentators who accused the film producers of fabricating a papal quote to market their movie.

On January 19, 2004, Gabriel Snyder reported in Variety that before McEveety spoke to Noonan, he had requested and received permission from the Vatican to use the "It is as it was" quote.[99] Two days later, after receiving a leaked copy of an email from someone associated with Gibson, Rod Dreher reported in the Dallas Morning News that McEveety was sent an email on December 28 allegedly from papal spokesman Navarro-Valls that supported the Noonan account, and suggested "It is as it was" could be used as the leitmotif in discussions on the film and said to "Repeat the words again and again and again."[100]

Further complicating the situation, on January 21[97] Dreher emailed Navarro-Valls a copy of the December 28 email McEveety had received, and Navarro-Valls emailed Dreher back and said, "I can categorically deny its authenticity."[100] Dreher opined that either Mel Gibson's camp had created "a lollapalooza of a lie", or the Vatican was making reputable journalists and filmmakers look like "sleazebags or dupes" and he explained:

Interestingly, Ms. Noonan reported in her Dec. 17 column that when she asked the spokesman if the pope had said anything more than "It is as it was," he e-mailed her to say he didn't know of any further comments. She sent me a copy of that e-mail, which came from the same Vatican email address as the one to me and to Mr. McEveety.[100]

On January 22, Noonan noted that she and Dreher had discovered the emails were sent by "an email server in the Vatican's domain" from a Vatican computer with the same IP address.[97] The Los Angeles Times reported that, when it asked on December 19 when the story first broke if the "It is as it was" quote was reliable, Navarro-Valls had responded "I think you can consider that quote as accurate."[101] In an interview with CNN on January 21, Vatican analyst John L. Allen Jr. noted that while Dziwisz stated that Pope John Paul II made no declaration about this movie, other Vatican officials were "continuing to insist" the pope did say it, and other sources claimed they had heard Dziwisz say the pope said it on other occasions, and Allen called the situation "kind of a mess".[102] A representative from Gibson's Icon Productions expressed surprise at Dziwisz's statements after the correspondence and conversations between film representatives and the pope's official spokesperson, Navarro-Valls, and stated "there is no reason to believe that the pope's support of the film 'isn't as it was.'"[99]

On January 22, after speaking to Dziwisz, Navarro-Valls confirmed John Paul II had seen The Passion of the Christ, and released the following official statement:

The film is a cinematographic transposition of the historical event of the Passion of Jesus Christ according to the accounts of the Gospel. It is a common practice of the Holy Father not to express public opinions on artistic works, opinions that are always open to different evaluations of aesthetic character.[98]

On January 22 in The Wall Street Journal, Noonan addressed the question of why the issues being raised were not just "a tempest in a teapot" and she explained:[97]

The truth matters. What a pope says matters. And what this pontiff says about this film matters. The Passion, which is to open on Feb. 25, has been the focus of an intense critical onslaught since last summer. The film has been fiercely denounced as anti-Semitic, and accused of perpetuating stereotypes that will fan hatred against Jews. John Paul II has a long personal and professional history of opposing anti-Semitism, of working against it, and of calling for dialogue, respect and reconciliation between all religions. His comments here would have great importance.

Allegations of antisemitism[]

Before the film was released, there were prominent criticisms of perceived antisemitic content in the film. It was for that reason that 20th Century Fox told New York Assemblyman Dov Hikind it had passed on distributing the film in response to a protest outside the News Corporation building. Hikind warned other companies that "they should not distribute this film. This is unhealthy for Jews all over the world."[34]

A joint committee of the Secretariat for Ecumenical and Inter-religious Affairs of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops and the Department of Inter-religious Affairs of the Anti-Defamation League obtained a version of the script before it was released in theaters. They released a statement, calling it

one of the most troublesome texts, relative to anti-Semitic potential, that any of us had seen in 25 years. It must be emphasized that the main storyline presented Jesus as having been relentlessly pursued by an evil cabal of Jews, headed by the high priest Caiaphas, who finally blackmailed a weak-kneed Pilate into putting Jesus to death. This is precisely the storyline that fueled centuries of anti-Semitism within Christian societies. This is also a storyline rejected by the Roman Catholic Church at Vatican II in its document Nostra aetate, and by nearly all mainline Protestant churches in parallel documents...Unless this basic storyline has been altered by Mr. Gibson, a fringe Catholic who is building his own church in the Los Angeles area and who apparently accepts neither the teachings of Vatican II nor modern biblical scholarship, The Passion of the Christ retains a real potential for undermining the repudiation of classical Christian anti-Semitism by the churches in the last 40 years.[103]

The ADL itself also released a statement about the yet-to-be-released film:

For filmmakers to do justice to the biblical accounts of the passion, they must complement their artistic vision with sound scholarship, which includes knowledge of how the passion accounts have been used historically to disparage and attack Jews and Judaism. Absent such scholarly and theological understanding, productions such as The Passion could likely falsify history and fuel the animus of those who hate Jews.[104]

Rabbi Daniel Lapin, the head of the Toward Tradition organization, criticized this statement, and said of Abraham Foxman, the head of the ADL, "what he is saying is that the only way to escape the wrath of Foxman is to repudiate your faith".[105]

In The Nation, reviewer Katha Pollitt wrote: "Gibson has violated just about every precept of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops own 1988 'Criteria' for the portrayal of Jews in dramatizations of the Passion (no bloodthirsty Jews, no rabble, no use of Scripture that reinforces negative stereotypes of Jews.) [...] The priests have big noses and gnarly faces, lumpish bodies, yellow teeth; Herod Antipas and his court are a bizarre collection of oily-haired, epicene perverts. The 'good Jews' look like Italian movie stars (Italian sex symbol Monica Bellucci is Mary Magdalene); Jesus's mother, who would have been around 50 and appeared 70, could pass for a ripe 35."[106] Jesuit priest Fr. William Fulco, S.J. of Loyola Marymount University—and the film's translator for Hebrew dialogue—specifically disagreed with that assessment, and disagreed with concerns that the film accused the Jewish community of deicide.[107]

One specific scene in the film perceived as an example of anti-Semitism was in the dialogue of Caiaphas, when he states "His blood [is] on us and on our children!"(Mt 27:25), a quote historically interpreted by some as a curse taken upon by the Jewish people. Certain Jewish groups asked this be removed from the film. However, only the subtitles were removed; the original dialogue remains in the Hebrew soundtrack.[108] When asked about this scene, Gibson said: "I wanted it in. My brother said I was wimping out if I didn't include it. But, man, if I included that in there, they'd be coming after me at my house. They'd come to kill me."[109] In another interview when asked about the scene, he said, "It's one little passage, and I believe it, but I don't and never have believed it refers to Jews, and implicates them in any sort of curse. It's directed at all of us, all men who were there, and all that came after. His blood is on us, and that's what Jesus wanted. But I finally had to admit that one of the reasons I felt strongly about keeping it, aside from the fact it's true, is that I didn't want to let someone else dictate what could or couldn't be said."[110]

Additionally, the film's suggestion that the Temple's destruction was a direct result of the Sanhedrin's actions towards Jesus could also be interpreted as an offensive take on an event which Jewish tradition views as a tragedy, and which is still mourned by many Jews today on the fast day of Tisha B'Av.[111]

Reactions to allegations of antisemitism[]

Film critic Roger Ebert, who awarded The Passion of the Christ 4 out of 4 stars in his review for the Chicago Sun-Times, denied allegations that the film was anti-semitic. Ebert described the film as "a powerful and important film, helmed by a man with a sincere heart and a warrior's sense of justice. It is a story filled with searing images and ultimately a message of redemption and hope." Ebert said "It also might just be the greatest cinematic version of the greatest story ever told."[112]

Conservative columnist Cal Thomas also disagreed with allegations of antisemitism, stating "To those in the Jewish community who worry that the film might contain anti-Semitic elements, or encourage people to persecute Jews, fear not. The film does not indict Jews for the death of Jesus."[113] Two Orthodox Jews, Rabbi Daniel Lapin and conservative talk-show host and author Michael Medved, also vocally rejected claims that the film is antisemitic. They said the film contains many sympathetic portrayals of Jews: Simon of Cyrene (who helps Jesus carry the cross), Mary Magdalene, the Virgin Mary, St. Peter, St. John, Veronica (who wipes Jesus' face and offers him water) and several Jewish priests who protest Jesus' arrest (Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea) during Caiaphas' trial of Jesus.

Bob Smithouser of Focus on the Family's Plugged In also believed that film was trying to convey the evils and sins of humanity rather than specifically targeting Jews, stating: "The anthropomorphic portrayal of Satan as a player in these events brilliantly pulls the proceedings into the supernatural realm—a fact that should have quelled the much-publicized cries of anti-Semitism since it shows a diabolical force at work beyond any political and religious agendas of the Jews and Romans."[62]

Moreover, senior officer at the Vatican Cardinal Darío Castrillón Hoyos, who had seen the film, addressed the matter so:

Anti-Semitism, like all forms of racism, distorts the truth in order to put a whole race of people in a bad light. This film does nothing of the sort. It draws out from the historical objectivity of the Gospel narratives sentiments of forgiveness, mercy, and reconciliation. It captures the subtleties and the horror of sin, as well as the gentle power of love and forgiveness, without making or insinuating blanket condemnations against one group. This film expressed the exact opposite, that learning from the example of Christ, there should never be any more violence against any other human being.[114]

Asked by Bill O'Reilly if his movie would "upset Jews", Gibson responded "It's not meant to. I think it's meant to just tell the truth. I want to be as truthful as possible."[115] In an interview for The Globe and Mail, he added: "If anyone has distorted Gospel passages to rationalize cruelty towards Jews or anyone, it's in defiance of repeated Papal condemnation. The Papacy has condemned racism in any form...Jesus died for the sins of all times, and I'll be the first on the line for culpability."[116]

South Park parodied the controversy in the episodes "Good Times with Weapons", "Up the Down Steroid" and "The Passion of the Jew", all of which aired just a few weeks after the film's release.

Criticism of excessive violence[]

A.O. Scott in The New York Times wrote "The Passion of the Christ is so relentlessly focused on the savagery of Jesus' final hours that this film seems to arise less from love than from wrath, and to succeed more in assaulting the spirit than in uplifting it."[117] David Edelstein, Slate's film critic, dubbed the film "a two-hour-and-six-minute snuff movie—The Jesus Chainsaw Massacre—that thinks it's an act of faith", and further criticized Gibson for focusing on the brutality of Jesus' execution, instead of his religious teachings.[76] In 2008, writer Michael Gurnow in American Atheists stated much the same, labeling the work a mainstream snuff film.[118] Critic Armond White, in his review of the film for Africana.com offered another perspective on the violence in the film. He wrote, "Surely Gibson knows (better than anyone in Hollywood is willing to admit) that violence sells. It's problematic that this time, Gibson has made a film that asks for a sensitive, serious, personal response to violence rather than his usual glorifying of vengeance."[74]

During Diane Sawyer's interview of him, Gibson said:

I wanted it to be shocking; and I wanted it to be extreme...So that they see the enormity of that sacrifice; to see that someone could endure that and still come back with love and forgiveness, even through extreme pain and suffering and ridicule. The actual crucifixion was more violent than what was shown on the film, but I thought no one would get anything out of it.

Sequel[]

In June 2016, writer Randall Wallace stated that he and Gibson had begun work on a sequel to The Passion of the Christ focusing on the resurrection of Jesus.[119] Wallace previously worked with Gibson as the screenwriter for Braveheart and director of We Were Soldiers.[120] In September of that year, Gibson expressed his interest in directing it. He estimated that release of the film was still "probably three years off",[121] stating that "it is a big project".[122] Calling it "a vast theological experience," Gibson said that the film delves into the meaning of the resurrection by juxtaposing the central event of Jesus' rising "with the many things going on around it and in other realms." It will make connections as a way "to enlighten what that means." He implied that part of the movie would be taking place in Hell and, while talking to Raymond Arroyo, said that it also may show flashbacks depicting the fall of the Angels.[123] The film will explore the three-day period starting on Good Friday, the day of Jesus' death, and will look at why the disciples did not recognize Jesus on the way to Emmaus.[124]

In January 2018, Caviezel was in agreements with Mel Gibson to reprise his role as Jesus in the sequel.[125] In March 2020, Caviezel stated in an interview that the film was in its fifth draft.[126] However, in September 2020, Caviezel then said that Gibson had sent him the third draft of the screenplay.[127][128]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "The Passion of the Christ (18)". British Board of Film Classification. February 18, 2004. Retrieved June 2, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "The Passion of the Christ (2004): summary". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Noonan, Peggy (December 17, 2003). "'It is as it was': Mel Gibson's The Passion gets a thumbs-up from the pope". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Father John O'Malley A Movie, a Mystic, a Spiritual Tradition America, March 15, 2004 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 5, 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Jesus and Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ by Kathleen E. Corley, Robert Leslie Webb. 2004. ISBN 0-8264-7781-X. pp. 160–161.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mel Gibson's Passion and philosophy by Jorge J. E. Gracia. 2004. ISBN 0-8126-9571-2. p. 145.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Movies in American History: An Encyclopedia edited by Philip C. Dimare. 2011. ISBN 1-59884-296-X. p. 909.

- ^ "The Passion of the Christ". Movie-Locations

- ^ "The Passion of the Christ". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- ^ "Christian Movies at the Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- ^ Gibson, Mel (February 25, 2004), The Passion of the Christ, retrieved September 1, 2016

- ^ The Holy Bible, Book of Revelation 21:5.

- ^ The Holy Bible, Book of Isaiah 53:5.

- ^ The Holy Bible, Book of Genesis 3:15.

- ^ Cooney Carrillo, Jenny (February 26, 2004). "The Passion of Mel". Urbancinefile. Archived from the original on June 1, 2004.

- ^ Abramowitz, Rachel (March 7, 2004). "Along came Mary; Mel Gibson was sold on Maia Morgenstern for 'Passion' at first sight". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Brentano, Clement. The Dolorous Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ.

- ^ Movies in American History: An Encyclopedia edited by Philip C. DiMare 2011 ISBN 1-59884-296-X p. 909

- ^ Jump up to: a b Emmerich, Anne Catherine, and Clemens Brentano. The Dolorous Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ. Anvil Publishers, Georgia, 2005 pp. 49–56

- ^ John Thavis, Catholic News Service February 4, 2004: "Vatican confirms papal plans to beatify nun who inspired Gibson film" [1]

- ^ John Thavis, Catholic News Service October 4, 2004: "Pope beatifies five, including German nun who inspired Gibson film" [2]

- ^ "Mel Gibson's great passion: Christ's agony as you've never seen it". Zenit News Agency. March 6, 2003. Archived from the original on August 15, 2009. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ 'Msgr. Charles Pope' "A Hidden, Mysterious, and Much Debated Word in the Our Father". May 6, 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Translating the passion". Language Hat. March 8, 2004.

- ^ Jarvis, Edward (2018). Sede Vacante: The Life and Legacy of Archbishop Thuc. Berkeley CA: The Apocryphile Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-1949643022.

- ^ Susman, Gary (October 24, 2003). "Charged Performance". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- ^ Ross, Scott (March 28, 2008). "Behind the Scenes of 'The Passion' with Jim Caviezel". Retrieved March 31, 2013.

- ^ "Jesus actor struck by lightning". BBC News. October 23, 2003. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ^ "Jack Lenz Bio". JackLenz.com. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015.

- ^ "Clips of Musical Compositions by Jack Lenz". JackLenz.com. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015.

- ^ Susman, Gary (October 16, 2004). "Napoleon Branding". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved August 16, 2008.

- ^ Vivarelli, Nick (September 23, 2002). "Gibson To Direct Christ Tale With Caviezel As Star". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ Patsuris, Penelope (March 3, 2004). "What Mel's Passion Will Earn Him". Forbes.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Fox passes on Gibson's 'The Passion'". Los Angeles Times. October 22, 2004. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ Horn, John (October 22, 2004). "Gibson to Market 'Christ' on His Own, Sources Say". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ Cobb, Jerry (February 25, 2004). "Marketing 'The Passion of the Christ'". NBC News.

- ^ Maresco, Peter A. (Fall 2004). "Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ: Market Segmentation, Mass Marketing and Promotion, and the Internet". Journal of Religion and Popular Culture. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Many churches look to 'Passion' as evangelism tool". United Methodist Church. Retrieved June 7, 2009.

- ^ ANN News Analysis: Adventists and "The Passion of the Christ", Adventist News Network, 23 February 2004

- ^ Pauley, John L.; King, Amy (2013). Woods, Robert H. (ed.). Evangelical Christians and Popular Culture. 1. Westport: Praeger Publishing. pp. 36–51. ISBN 978-0313386541.

- ^ Pawley, p. 38.

- ^ Pawley, p. 40.

- ^ Pawley, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pauley, p. 41.

- ^ Fredriksen, Paula (2006). On 'The Passion of the Christ': Exploring the Issues Raised by the Controversial Movie. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520248533.[page needed]

- ^ "All time box office: domestic grosses by MPAA rating". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- ^ DeSantis, Nick (February 22, 2016). "'Deadpool' Box Office On Pace To Dethrone 'Passion Of The Christ' As Top-Grossing R-Rated Movie Of All Time". Forbes. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (February 27, 2016). "Powerless Versus 'Deadpool', 'Gods of Egypt' Is First 2016 Big-Budget Bomb: Saturday AM B.O. Update". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (February 28, 2016). "Box Office: 'Deadpool' Entombs Big-Budget Bomb 'Gods of Egypt' to Stay No. 1". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (March 6, 2016). "Box Office: 'Zootopia' Defeats 'Deadpool' With Record $73.7M". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "The Passion of the Christ (2004): domestic total estimated tickets". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ "'The Passion of the Christ': "A milestone in the cinema history"". Asia News. PIME Onlus – AsiaNews. April 7, 2004. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ "The Passion Of The Christ Goes International". Worldpress.org. May 2004. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

A Philippine student shows a pirated DVD copy of The Passion of the Christ, which opened in local theaters, March 31, 2004.

- ^ Flores, Wilson Lee (March 29, 2004). "Mel Gibson's 'Passion' is powerful, disturbing work of art". Philstar.com. Gottingen, Germany: Philstar Global Corp. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Aravilla, Jose (March 11, 2004). "Bishops endorse Mel Gibson film". Philstar.com. Philstar Global Corp. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ "Censors in Malaysia give OK to 'Passion'". Los Angeles Times. July 10, 2004. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ King, Laura (March 15, 2004). "'Passion' goes unseen in Israel". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ Blanford, Nicholas (April 9, 2004). "Gibson's movie unlikely box-office hit in Arab world". The Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ "2004 Box Office Totals for Egypt". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- ^ O'Neill, Eddie (February 2, 2014). "'The Passion of the Christ', a Decade Later". National Catholic Register. Retrieved July 31, 2014.

- ^ Frater, Patrick (August 8, 2017). "'Wolf Warriors II' Takes All Time China Box Office Record". Variety. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "The Passion of the Christ Review". Plugged In. Archived from the original on December 30, 2012.

- ^ "The Passion Recut: domestic total gross". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hettrick, Scott (September 1, 2004). "DVD buyers express 'Passion'". Variety. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- ^ Associated Press (September 1, 2004). "Passion DVD sells 4.1 million in one day". Today. Retrieved October 13, 2019.

- ^ Gibson, Mel. The Passion of the Christ (Blu-ray; visual material) (in Latin and Hebrew) (definitive ed.). Beverly Hills, California: 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment. OCLC 302426419. Retrieved March 29, 2013. Lay summary – Amazon.

- ^ Papamichael, Stella. "The Passion of the Christ: Special Edition DVD". BBC. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ^ "Mel Gibson's 'The Passion of the Christ' Returns to Blu-ray". High-Def Digest.

- ^ "The Passion of the Christ". TBN. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ^ "The Passion of the Christ (2004)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "The Passion of the Christ (2004): reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (August 19, 2011). "Why CinemaScore Matters for Box Office". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on July 19, 2021. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ White, Armond (March 18, 2008). "Steve McQueen's Hunger". New York Press. Archived from the original on April 23, 2009. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b White, Armond (February 26, 2004). "Africana Reviews: The Passion of the Christ (web archive)". Archived from the original on March 12, 2004.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (February 24, 2004). "The Passion of the Christ". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved August 2, 2006 – via rogerebert.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Edelstein, David (February 24, 2004). "Jesus H. Christ". Slate. Archived from the original on November 23, 2009.

- ^ Bernard, Jami (February 24, 2004). "The Passion of the Christ". New York Daily News. New York City: Tronc. Archived from the original on April 16, 2004.

- ^ "Entertainment Weekly". June 2006. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Sanburn, Josh (September 3, 2010). "Top 10 Ridiculously Violent Movies". Time. New York City. Archived from the original on September 5, 2010. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

- ^ "Film prompts murder confession". Edinburgh: News.scotsman.com. March 27, 2004. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ^ "Mel Gibson". IMDb. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- ^ "Hollywood Awards ... and the winners are ..." Hollywood Film Awards. October 19, 2004. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- ^ Золотой Орел 2004 [Golden Eagle 2004] (in Russian). Ruskino.ru. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's Top 10 Epic Nominations". Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ "Never Seen It".

- ^ Goodacre, Mark (May 2, 2004). "Historical Accuracy of The Passion of the Christ". Archived from the original on October 13, 2008.

- ^ Mark Goodacre, "The Power of The Passion: Reacting and Over-reacting to Gibson's Artistic Vision" in "Jesus and Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ. The Film, the Gospels and the Claims of History", ed. Kathleen E. Corley and Robert L. Webb, 2004

- ^ Neff, David, and Struck, Jane Johnson (February 23, 2004). "'Dude, that was graphic': Mel Gibson talks about The Passion of The Christ". Christianity Today. Archived from the original on July 9, 2008. Retrieved October 20, 2008.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Moring, Mark (March 1, 2004). "What's up with the ugly baby?". Christianity Today. Archived from the original on July 9, 2008. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- ^ "Mel Gibson's Passion: on review at the Vatican". Zenit News Agency. December 8, 2003. Archived from the original on September 14, 2012. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ Flynn, J. D. (December 18, 2003). "Pope John Paul endorses The Passion of Christ with five simple words". Catholic News Agency. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Allen, John L. Jr. (January 9, 2004)."U.S. bishops issue abuse report; more on The Passion ...". National Catholic Reporter: The Word from Rome. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rich, Frank (January 18, 2014). "The pope's thumbs up for Gibson's Passion". The New York Times Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wooden, Cindy (January 19, 2004). "Pope never commented on Gibson's 'Passion' film, says papal secretary". Catholic News Service. Archived from the original on January 24, 2004.

- ^ Vivarelli, Nick (December 15, 2003)."Pope peeks at private Passion preview". Variety. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Noonan, Peggy (January 22, 2004). "The story of the Vatican and Mel Gibson's film gets curiouser". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Allen, John L. Jr. (January 23, 2004)."Week of prayer for Christian unity; update on The Passion ...". National Catholic Reporter: The Word from Rome. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Snyder, Gabriel (January 19, 2004)."Did Pope really plug Passion? Church denies papal support of Gibson's pic". Variety. Archived from the original on December 19, 2008. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Dreher, Rod (January 21, 2004)."Did the Vatican endorse Gibson's film – or didn't it?" Dallas Morning News. Archived from the original on January 27, 2012. Retrieved October 19, 2008.

- ^ Munoz, Lorenza and Stammer, Larry B. (January 23, 2004)." Fallout over Passion deepens". The Los Angeles Times. Contributions by Greg Braxton and the Associated Press. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ "Transcripts: The Passion stirs controversy at the Vatican". CNN. Miles O'Brien interview with John L. Allen Jr. on January 21, 2004. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ^ Pawlikowski, John T. (February 2004). "Christian Anti-Semitism: Past History, Present Challenges Reflections in Light of Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ". Journal of Religion and Film. Archived from the original on August 20, 2006.

- ^ "ADL Statement on Mel Gibson's 'The Passion'" (Press release). Anti-Defamation League. June 24, 2003. Archived from the original on July 23, 2008.

- ^ Cattan, Nacha (March 5, 2004). "'Passion' Critics Endanger Jews, Angry Rabbis Claim, Attacking Groups, Foxman". The Jewish Daily Forward.

- ^ Pollitt, Katha (March 11, 2004). "The Protocols of Mel Gibson". The Nation. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- ^ Wooden, Cindy (May 2, 2003). "As filming ends, 'Passion' strikes some nerves". National Catholic Reporter. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- ^ Vermes, Geza (February 27, 2003). "Celluloid brutality". The Guardian. London. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- ^ "The Jesus War".

- ^ Lawson, Terry (February 17, 2004). "Mel Gibson and Other 'Passion' Filmakers say the Movie was Guided by Faith". Detroit Free Press.[dead link]

- ^ Markoe, Lauren (July 15, 2013). "Tisha B'Av 2013: A New Approach To A Solemn Jewish Holiday". Huffington Post.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (March 30, 2004). "Judge ye not Gibson's film until you've actually seen it". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ "The Greatest Story Ever Filmed". TownHall.com. August 5, 2003.

- ^ Gaspari, Antonio (September 18, 2003). "The Cardinal & the Passion". National Review Online. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (January 19, 2003). "The Passion of Mel Gibson". Time. Archived from the original on October 26, 2004. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ^ "Mel Gibson Interview". The Globe and Mail. February 14, 2004.

- ^ A. O. Scott (February 25, 2004). "Good and Evil Locked in Violent Showdown". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 13, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2007.

- ^ Gurnow, Michael (April 2008). "The passion of the snuff: how the MPAA allowed a horror film to irreparably scar countless young minds in the name of religion" (PDF). American Atheists. pp. 17–18. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 18, 2015. Retrieved February 17, 2014.

- ^ Bond, Paul (June 9, 2016)."Mel Gibson planning Passion of the Christ sequel (exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 13, 2019.

- ^ Dostis, Melanie (June 9, 2019)."Mel Gibson is working on a Passion of the Christ sequel". New York Daily News. Retrieved October 13, 2019.

- ^ "Mel Gibson Confirms Sequel To 'Passion Of The Christ'" (Interview).

- ^ Mike Fleming Jr (September 6, 2016). "Mel Gibson On His Venice Festival Comeback Picture 'Hacksaw Ridge' – Q&A". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ^ "Gibson on Passion of the Christ Sequel, The Resurrection" (Interview).

- ^ Scott, Ryan (November 2, 2016)."'Passion of the Christ 2' gets titled Resurrection, may take Jesus to Hell". MovieWeb. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ^ Bond, Paul (January 30, 2018). "Jim Caviezel in Talks to Play Jesus in Mel Gibson's 'Passion' Sequel". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved March 2, 2020.

- ^ "'The Passion of the Christ' actor: Painful movie 'mistakes' made hit film 'more beautiful'". Fox Nation. March 23, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- ^ Burger, John (September 25, 2020). "Jim Caviezel to play Jesus again in sequel to 'The Passion of Christ'". Aleteia. Aleteia SAS. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

- ^ Guno, Nina V. (September 24, 2020). "'Passion of the Christ 2' is coming, says Jim Caviezel". Inquirer Entertainment. INQUIRER.net. Retrieved October 7, 2020.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Passion of the Christ |

- The Passion of the Christ at IMDb

- The Passion of the Christ at the TCM Movie Database

- The Passion of the Christ at AllMovie

- The Passion of the Christ at Box Office Mojo

- The Passion of the Christ at Metacritic

- The Passion of the Christ at Rotten Tomatoes

- 2004 films

- The Passion of the Christ

- 2000s multilingual films

- 2004 drama films

- American drama films

- American epic films

- American films

- American independent films

- American multilingual films

- Aramaic-language films

- Caiaphas

- Censored films

- Films about Christianity

- Christianity in popular culture controversies

- Cultural depictions of Judas Iscariot

- Cultural depictions of Pontius Pilate

- Cultural depictions of Saint Peter

- Film portrayals of Jesus' death and resurrection

- Films about capital punishment

- Films directed by Mel Gibson

- Films produced by Bruce Davey

- Films produced by Mel Gibson

- Films scored by John Debney

- Films shot in Matera

- Films shot in Rome

- Films with screenplays by Mel Gibson

- Hebrew-language films

- Icon Productions films

- Latin-language films

- Judaism-related controversies

- Obscenity controversies in film

- Religious controversies in film

- Portrayals of Jesus in film

- Portrayals of Mary Magdalene in film

- Portrayals of the Virgin Mary in film

- Religious epic films

- Scanbox Entertainment films

- Torture in films

- Golden Eagle Award (Russia) for Best Foreign Language Film winners