Asbury Park Convention Hall

| |

| |

| Address | 1300 Ocean Avenue |

|---|---|

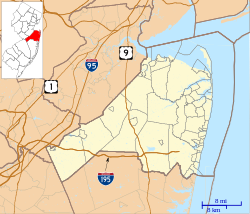

| Location | Asbury Park, New Jersey |

| Public transit | NJ Transit

|

Asbury Park Convention Hall | |

U.S. National Register of Historic Places | |

| |

| Location | Ocean Avenue, Asbury Park, New Jersey |

| Coordinates | 40°13′25″N 73°59′56″W / 40.22361°N 73.99889°WCoordinates: 40°13′25″N 73°59′56″W / 40.22361°N 73.99889°W |

| NRHP reference No. | 79001512[1] |

| NJRHP No. | 1952[2] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | March 2, 1979 |

| Designated NJRHP | December 28, 1978 |

| Owner | City of Asbury Park |

| Type | Convention hall |

| Capacity | 3,600 |

| Opened | 1925 |

| Tenants | |

| New Jersey ShoreCats (USBL) (1998–2000) Jersey Shore Roller Girls (WFTDA) (2008–present) | |

| Website | |

| apboardwalk | |

Asbury Park Convention Hall is a 3,600-seat indoor exhibition center located on the boardwalk and on the beach in Asbury Park, Monmouth County, New Jersey, United States. It was built between 1928 and 1930 and is used for sports, concerts and other special events. Adjacent to the Convention Hall is the Paramount Theatre; both are connected by a Grand Arcade. Both structures are listed in the National Register of Historic Places.[3]

History[]

In 1916, Asbury Park Mayor hired famed architectural firm McKim, Mead and White to design a convention center for the block just north of the city's Atlantic Square, between 6th and Sunset avenues. The firm submitted a plan that called for a 5,000-seat venue costing $75,000 to construct. However, city founder James A. Bradley owned the block in question, then home to the aging , and refused to sell the plot to the city. After Bradley's death in 1921, department store scion Arthur Steinbach purchased the Auditorium property from Bradley's estate, demolished the auditorium, and constructed the Berkeley-Carteret Hotel on the plot.

The completion of the third Madison Square Garden in New York City, and the approval of Atlantic City's new Convention Hall, put Hetrick under considerable pressure to construct a similar venue for Asbury Park. "While we have hesitated, Atlantic City has added $100 million in valuations," he told the Asbury Park Press. "While the Traymores and Breakers and other imposing structures have been built over a period of 25 years, we can show only the Monterey, the Berkeley-Carteret, the Asbury-Carlton and the Palace", referring to four then-new seasonal hotels in the resort city.

In 1927, after a mysterious fire destroyed the 5th Avenue Arcade just east of Atlantic Square on the Boardwalk, voters passed a bond referendum to construct a new convention center on the plot. Hetrick commissioned architects Warren and Wetmore, who also designed New York City's Grand Central Terminal. The firm's eventual design called for a 1,600-seat theatre to occupy the old 5th Avenue Arcade plot. The theatre was connected to an enclosed arcade that covered the boardwalk. This arcade was connected on the east to a 3,200-seat convention center, offering 60,000 square feet (5,600 m2) of exhibition space. This portion, which would be christened "Convention Hall", extended 215 feet (66 m) over the beach and the waterline, and was supported by steel encased concrete pilings. From the time of its construction until a seawall construction project in the 1970s, visitors to the hall could look directly over the Atlantic Ocean from the hall's easternmost outer walkway.[4] Heat was provided in colder months by a system of underground pipes connected to a city-owned steam plant, located at the southernmost end of the Boardwalk. The entire complex was designed in a combination Italian-French style, with an emphasis on nautical themes in recognition of its oceanfront location.

WCAP[]

In 1927, AM radio station WDWM moved from its studios in Newark to downtown Asbury Park, changing its call letters to WCAP for "Wonder City of Asbury Park". The Chamber of Commerce, which owned the station, moved it again into a studio on the northern second-floor promenade of Convention Hall in the fall of 1931. Warren & Wetmore had wired the hall for radio capability, and the on-hand studio allowed the station to broadcast live performances from the venue by the Arthur Pryor Band and the Berkeley-Carteret Orchestra, among other acts. The station broadcast from Convention Hall until 1944, when Walter Reade Theatres and the Charms Candy Company bought the station and moved its studios back to the downtown area. The station switched to FM in 1947. Three years later, the Asbury Park Press purchased the station and changed its call letters to WJLK. It continues to broadcast today from studios in the former Seaview Square Mall in nearby Ocean Township.[5]

Convention Hall's Role in the Morro Castle Disaster[]

On September 8, 1934, the cruise ship SS Morro Castle caught fire off Long Beach Island as she was returning to New York from Havana. After the Morro Castle could no longer sail under her own power, the Coast Guard cutter Tampa attempted to tow the damaged ship from eight miles (13 km) off the coast of Sea Girt to New York. However, rough seas from a nor'easter snapped the tow lines, and the Morro Castle drifted toward shore. WCAP radio announcer Tom Burley was broadcasting from the station's Convention Hall studios on the second floor promenade at about 7:30 p.m. when he first spotted the burning hulk of the ship approaching the beach. As the wire services already knew about the disaster, which had started early that morning, Burley led off his newscast with a straight update about the Morro Castle. A few minutes later, he saw the burning hulk of the ship slowly drifting toward Convention Hall and exclaimed on air, "She's here! The Morro Castle is coming right toward our studio!"[5]

The ship eventually came to rest on a sandbar several yards in front of Convention Hall, with her stern perpendicular to the hall's oceanfront promenade. The following morning, with the hull still smoldering, city engineer James Kontajones and Coast Guard inspector R.W. Hodge paddled out to the stern from a lifeguard boat and climbed up to the deck via one of the ropes hanging down from the ship's D Deck railing. The Coast Guard then used a Lyle gun to fire several ropes to the Morro Castle stern from Convention Hall. Kontajones and Hodge used the ropes to rig together a breeches buoy, facilitating passage for firemen, inspectors, local officials, and other authorities who needed to board the ship to search it for victims or anything of value. No living people were found on the ship and most of the decks and cabins were gutted by the massive fire. All told, 137 crew and passengers lost their lives in the disaster. Most of the victims either burned to death or died from smoke inhalation. Some victims' remains were found on the open decks and in the cabins below.

The Morro Castle remained on the sandbar throughout the fall and winter, spurring an economic boomlet for Asbury Park, which had been suffering from the effects of the Great Depression. Thousands of curious spectators and reporters lined both the boardwalk and Convention Hall's promenade to see the ship's charred remains, and both city officials and unlicensed individuals charged upwards of $5 to ride the breeches buoy onto the deck. On March 14, 1935, what remained of the Morro Castle was finally towed to New York's Gravesend Bay to be scrapped.[6][7]

The Kilgen Pipe Organ[]

Much like its counterpart in Atlantic City, Convention Hall was originally designed with the intention of installing a large Wurlitzer Pipe Organ for public performance. Warren and Wetmore strategically placed massive grille work into the walls on either side of the hall's main stage.[8] These grilles would cover the organ's pipes while taking advantage of the interior acoustics, making the entire hall part of the instrument.[9] The Great Depression forced the city to abandon the original idea of buying a Wurlitzer. After the closing of the Earl Carroll Theatre in New York City in 1931, however, Asbury Park purchased that theatre's 3 manual/7 rank pipe organ and installed it in Convention Hall. It had been built three years earlier by George Kilgen & Sons of St. Louis. Though measurably smaller than the Wurlitzer for which Convention Hall had been built, the Kilgen managed to sound much larger with the help of the hall's acoustics.

In the 1930s, Asbury Park created the position of municipal organist. The first, G. Howard Scott, would play free concerts to entertain visitors to the resort's boardwalk. WCAP would broadcast some of these concerts to its listeners from its studio at the hall. Jim Ryan took over in 1958, performing until the mid-1970s. The final municipal organist was Al Devivo, who performed from then until 1984, when the municipal concerts ceased.

The organ continued to be played intermittently from 1984 through 2000, most famously by composer and Radio City Music Hall organist Ashley Miller. During this time, volunteers from the Garden State Theatre Organ Society began refurbishing the instrument by cleaning or replacing pipes and adding five more ranks, resulting in an even fuller sound. In 1991, the console - traditionally in a stationary position underneath the southernmost grille - was made mobile so as to allow performers to play the instrument closer to the audience.[8] With the fate of the hall left in limbo by Asbury Park's long-delayed redevelopment plans, however, access to the instrument was eventually denied and it has lain dormant for most of the 2000s. It remains one of only two Kilgen organs left in New Jersey.

Meetings and events[]

The first official convention held at Convention Hall was the annual meeting of the New York Friars' Club on July 5, 1930.[10] Since that time, the hall has hosted countless conventions, community meetings, sporting events, trade shows and antique automobile shows. Since 1951, the Monmouth County Cotillion Society has held its annual Debutante Ball at Convention Hall.[11] The hall is also the alternate venue for Asbury Park's Easter Parade in the event of inclement weather.

Since February 2008, Convention Hall has been the home venue for the Jersey Shore Roller Girls roller derby league.[12]

Concerts[]

Rock and roll has been a mainstay at Convention Hall since the 1950s. On June 30, 1956, a concert by Frankie Lymon & The Teenagers at the Hall ended, prematurely, when a fistfight in the audience erupted into a full-scale riot. Three people were stabbed and then-Mayor Roland J. Hines threatened a citywide ban on rock and roll performances. The ban never came to pass.[10] In the mid-1960s, promoter Moe Septee started booking rock acts at Convention Hall, including some bands who would go on to achieve legendary status.

Between 1965 and 1975, Septee booked Black Sabbath, The Beach Boys, James Brown, The Byrds, Ray Charles, Chicago, The Dave Clark Five, The Doors, The J. Geils Band, Herman’s Hermits, Janis Joplin, Iron Butterfly, Otis Redding, KISS, The Rolling Stones, The Temptations, Pink Floyd and The Who, among many others.[13] Led Zeppelin played Convention Hall the evening of August 16, 1969, after their manager, Peter Grant, rejected an invitation to Woodstock. Joe Cocker opened for Led Zeppelin that night, before riding up to Bethel, New York for his opening slot on the festival's third and final (scheduled) day.[14]

The hall was also the setting for one of the last few concerts played by the original Lynyrd Skynyrd lineup on July 13, 1977, before their tour plane's fatal crash on October 20, 1977.

Concerts at Convention Hall continued even after Septee's retirement. From the late 1970s to the 1990s, acts including The Allman Brothers Band, Judas Priest, Iron Maiden, Korn, Marilyn Manson, Earth Crisis, Blue Öyster Cult, Tool, Ted Nugent, King Crimson, Peter Gabriel, Elvis Costello, The Clash, Van Halen, Blondie, The Kinks, Joe Jackson, No Doubt and The Goo Goo Dolls played the hall.[15]

Beginning in the late 1990s Convention Hall gained a strong association with Bruce Springsteen.[3] He held rehearsals for upcoming tours there (with fans standing outside to get early ideas of what the shows would bring),[3] some ticketed public rehearsal shows, and several December holiday shows in conjunction with The Max Weinberg 7. The large lighted sign on the top of Convention Hall reads "Greetings from Asbury Park", in reference to Springsteen's 1973 debut album Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J.In late 2020 Asbury Audio, the company that handles the concert and event production for the venue owners restored the sign with LED lighting.

During the 2000s, acts have included 311, Bob Dylan, Deftones, Incubus, Killswitch Engage, Slipknot, Pantera, Mudvayne, Hatebreed, Taproot, Seether, Papa Roach, Disturbed, Kittie, Fear Factory, Slaves On Dope, Boy Hits Car, Staind, 50 Cent, Tiesto, The Gaslight Anthem, Bouncing Souls, Face to Face, Thrice, Furthur, Jimmy Eat World, The Starting Line, and Dream Theater. By this time, Convention Hall had neither heating nor air conditioning.[3] At the Hall there were 4 Ford 6cyl engines that ran on natural gas to run the A/C and the Paramount had 40 hp Allis Electric motors to run theirs.

Gallery[]

Asbury Park Grand Arcade at Convention Hall

Angels over the vestibule in Convention Hall.

Interior of Convention Hall.

Southeast side of Convention Hall as seen from the Atlantic Ocean.

Detail of vestibule stairway.

Entry into Convention Hall through the Grand Arcade.

"Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J." echo its most famous near-resident artist.

Convention Hall is used as a venue for the roller derby.

References[]

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ^ "New Jersey and National Registers of Historic Places - Monmouth County" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection - Historic Preservation Office. March 1, 2011. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2011. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kiniry, Laura (2009). Moon New Jersey (2nd ed.). PublicAffairs. p. 137. ISBN 1-59880-156-2.

- ^ "S. Harris Ltd. Crack Gauge Monitoring" "In the early 1970s, a seawall was constructed to the east of the building and a jetty to the north, to prevent the water from breaking on the piers."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jaker, Bill; et al. (1998). The Airwaves of New York: Illustrated Histories of 156 AM Stations in the Metropolitan Area, 1921–1996. McFarland, pp 49 ISBN 0-7864-0343-8

- ^ Hicks, Brian. (2006). When the Dancing Stopped: The Real Story of the Morro Castle Disaster and Its Deadly Wake Simon and Schuster, pp 162 ISBN 0-7432-8008-3

- ^ Gallagher, Thomas Michael. (2003). Fire at Sea: The Mysterious Tragedy of the Morro Castle Globe Pequot, pp 162 ISBN 1-58574-624-X

- ^ Jump up to: a b [Garden State Theatre Organ Society "Program for the 1992 Summer Pops Concert Series"]

- ^ DeMasters, Karen. "JERSEY FOOTLIGHTS: New Life For Asbury Park Organ", The New York Times January 23, 2000. Accessed on April 19, 2009

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pike, Helen-Chantal (2005). Asbury Park's Glory Days: The Story of an American Resort. Rutgers University Press, pp 54,75 ISBN 0-8135-3547-6

- ^ "Monmouth County Cotillion Society newsletter" Archived August 13, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Jersey Shore Roller Girls Home Page" Archived April 29, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Golden, Peter "Shore Lore: Music Man" New Jersey Monthly February 2008. Accessed on April 19, 2008.

- ^ "Led Zeppelin's Official Site"

- ^ Wien, Gary; Rothenberg, Debra L. (2003). Beyond The Palace. Trafford Publishing, pp 15 ISBN 1-4120-0314-8

External links[]

- Garden State Theatre Organ Society page on the Kilgen Organ

- Restoration Photos of Convention Hall and Carousel, 2007–2008 Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Jersey Shore Roller Girls official Web site

- Footage of The Doors performing at Convention Hall, August 13, 1968. Shows Jim Morrison and John Densmore looking out over the ocean from the eastern promenade, pre-seawall project.

- Vintage postcards and photographs of The Convention Hall

- Sports venues in New Jersey

- Music venues in New Jersey

- Indoor arenas in New Jersey

- Warren and Wetmore buildings

- Asbury Park, New Jersey

- Buildings and structures in Monmouth County, New Jersey

- National Register of Historic Places in Monmouth County, New Jersey

- New Jersey Register of Historic Places

- Event venues on the National Register of Historic Places in New Jersey