Assisted suicide

| Suicide |

|---|

Assisted suicide, also known as assisted dying or medical aid in dying, is suicide undertaken with the aid of another person.[1] The term usually refers to physician-assisted suicide (PAS), which is suicide that is assisted by a physician or other healthcare provider. Once it is determined that the person's situation qualifies under the physician-assisted suicide laws for that place, the physician's assistance is usually limited to writing a prescription for a lethal dose of drugs.

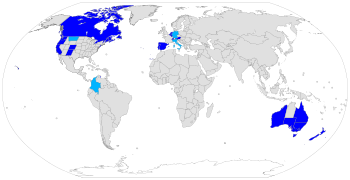

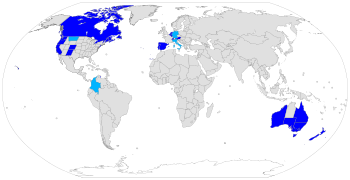

In many jurisdictions, helping a person die by suicide is a crime.[2] People who support legalizing physician-assisted suicide want the people who assist in a voluntary death to be exempt from criminal prosecution for manslaughter or similar crimes. Physician-assisted suicide is legal in some countries, under certain circumstances, including Belgium, Canada, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Spain, Switzerland, parts of the United States (California, Colorado, Hawaii, Maine, Montana, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oregon, Vermont, Washington State and Washington, D.C.) and Australia (Tasmania, Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia). The Constitutional Courts of Austria, Colombia, Germany and Italy legalized assisted suicide, but their governments have not legislated or regulated the practice yet. New Zealand legalized assisted suicide in a referendum in 2020, but it will come into force on 6 November 2021. The parliament of Portugal passed the legalization of assisted suicide, but is now under consideration of the Constitutional Court.

In most of those states or countries, to qualify for legal assistance, individuals who seek a physician-assisted suicide must meet certain criteria, including: having a terminal illness, proving they are of sound mind, voluntarily and repeatedly expressing their wish to die, and taking the specified, lethal dose by their own hand.

Terminology[]

Suicide is the act of killing oneself. Assisted suicide is when another person materially helps an individual person die by suicide, such as providing tools or equipment, while Physician-assisted suicide involves a physician (doctor) "knowingly and intentionally providing a person with the knowledge or means or both required to commit suicide, including counseling about lethal doses of drugs, prescribing such lethal doses or supplying the drugs".[4]

Assisted suicide is contrasted to Euthanasia, sometimes referred to as mercy killing, where the person dying does not directly bring about their own death, but is killed in order to stop the person from experiencing further suffering. Euthanasia can occur with or without consent, and can be classified as voluntary, non-voluntary or involuntary. Killing a person who is suffering and who consents is called voluntary euthanasia. This is currently legal in some regions.[5] If the person is unable to provide consent it is referred to as non-voluntary euthanasia. Killing a person who does not want to die, or who is capable of giving consent and whose consent has not been solicited, is the crime of involuntary euthanasia, and is regarded as murder.

Right to die is the belief that people have a right to die, either through various forms of suicide, euthanasia, or refusing life-saving medical treatment.

Suicidism can be definied as "the quality or state of being suicidal"[6] or as "[...] an oppressive system (stemming from non-suicidal perspectives) functioning at the normative, discursive, medical, legal, social, political, economic, and epistemic levels in which suicidal people experience multiple forms of injustice and violence [...]" [7]

Assisted dying vs assisted suicide[]

Some advocates for assisted suicide strongly oppose the use of "assisted suicide" and "suicide" when referring to physician-assisted suicide, and prefer the phrase "assisted dying". The motivation for this is to distance the debate from the suicides commonly performed by those not terminally ill and not eligible for assistance where it is legal. They feel those cases have negatively impacted the word "suicide" to the point that it bears no relation to the situation where someone who is suffering irremediably seeks a peaceful death.[8][9]

The oppression of suicidal people[]

''Suicidal people constitute an oppressed group whose claims remain unintelligible within society, law, medical/psychiatric systems and LGBTQ scholarship."[10] The wish to die of suicidal people and suicidal attempt are judged as irrational or illegitimate.[7] It leads to an injunction to live and to futurity where suicidal people must be kept alive.[10] Baril uses the term suicidism to describe this oppression. To reduce the oppression of suicidal people, Alexandre Baril, a professor in social work, suggest to validate suicidal ideation as a legitimate experience and create a welcoming environment to listen to their voice.[11]

Physician-assisted suicide[]

Support[]

Arguments for[]

Arguments in support of assisted death include respect for patient autonomy, equal treatment of terminally ill patients on and off life support, compassion, personal liberty, transparency[12] and ethics of responsibility.[7] When death is imminent (half a year or less) patients can choose to have assisted death as a medical option to shorten what the person perceives to be an unbearable dying process. Pain is mostly not reported as the primary motivation for seeking physician-assisted suicide in the United States;[13] the three most frequently mentioned end‐of‐life concerns reported by Oregon residents who took advantage of the Death With Dignity Act in 2015 were: decreasing ability to participate in activities that made life enjoyable (96.2%), loss of autonomy (92.4%), and loss of dignity (75.4%).[14]

Oregon statistics[]

A study of hospice nurses and social workers in Oregon reported that symptoms of pain, depression, anxiety, extreme air hunger and fear of the process of dying were more pronounced among hospice patients who did not request a lethal prescription for barbiturates, the drug used for physician assisted death.[15]

A Journal of Palliative Medicine report on patterns of hospice use noted that Oregon was in both the highest quartile of hospice use and the lowest quartile of potentially concerning patterns of hospice use. A similar trend was found in Vermont, where aid-in-dying (AiD) was authorized in 2013.[16]

In February 2016, Oregon released a report on their 2015 numbers. During 2015, there were 218 people in the state who were approved and received the lethal drugs to end their own life. Of that 218, 132 terminally ill patients ultimately made the decision to ingest drugs, resulting in their death. According to the state of Oregon Public Health Division's survey, the majority of the participants, 78%, were 65 years of age or older and predominately white, 93.1%. 72% of the terminally ill patients who opted for ending their own lives had been diagnosed with some form of cancer. In the state of Oregon's 2015 survey, they asked the terminally ill who were participating in medical aid in dying, what their biggest end-of-life concerns were: 96.2% of those people mentioned the loss of the ability to participate in activities that once made them enjoy life, 92.4% mentioned the loss of autonomy, or their independence of their own thoughts or actions, and 75.4% stated loss of their dignity.[17]

Washington State statistics[]

An increasing trend in deaths caused from ingesting lethal doses of medications prescribed by physicians was also noted in Washington: from 64 deaths in 2009 to 202 deaths in 2015.[18] Among the deceased, 72% had terminal cancer and 8% had neurodegenerative diseases (including ALS).[18]

U.S. polls[]

Polls conducted by Gallup dating back to 1947 positing the question, "When a person has a disease that cannot be cured, do you think doctors should be allowed to end the patient's life by some painless means if the patient and his family request it?" show support for the practice increasing from 37% in 1947 to a plateau of approximately 75% lasting from approximately 1990 to 2005. When the polling question was modified as such so the question posits "severe pain" as opposed to an incurable disease, "legalization" as opposed to generally allowing doctors, and "patient suicide" rather than physician-administered voluntary euthanasia, public support was substantially lower, by approximately 10% to 15%.[13]

A poll conducted by National Journal and Regence Foundation found that both Oregonians and Washingtonians were more familiar with the terminology "end-of-life care" than the rest of the country and residents of both states are slightly more aware of the terms palliative and hospice care.[19]

A survey from the Journal of Palliative Medicine found that family caregivers of patients who chose assisted death were more likely to find positive meaning in caring for a patient and were more prepared for accepting a patient's death than the family caregivers of patients who didn't request assisted death.[20]

Safeguards[]

Many current assisted death laws contain provisions that are intended to provide oversight and investigative processes to prevent abuse. This includes eligibility and qualification processes, mandatory state reporting by the medical team, and medical board oversight. In Oregon and other states, two doctors and two witnesses must assert that a person's request for a lethal prescription wasn't coerced or under undue influence.

These safeguards include proving one's residency and eligibility. The patient must meet with two physicians and they must confirm the diagnoses before one can continue the procedure; in some cases, they do include a psychiatric evaluation as well to determine whether or not the patient is making this decision on their own. The next steps are two oral requests, a waiting period of a minimum of 15 days before making the next request. A written request which must be witnessed by two different people, one of which cannot be a family member, and then another waiting period by the patient's doctor in which they say whether they are eligible for the drugs or not ("Death with Dignity").

The debate about whether these safeguards work is debated between opponents and proponents.

Religious stances[]

Unitarian Universalism[]

According to a 1988 General Resolution, "Unitarian Universalists advocate the right to self-determination in dying, and the release from civil or criminal penalties of those who, under proper safeguards, act to honor the right of terminally ill patients to select the time of their own deaths".[21]

Opposition[]

Medical ethics[]

Code of Ethics[]

The most current version of the American Medical Association's Code of Ethics states that physician-assisted suicide is prohibited. It prohibits physician-assisted suicide because it is "fundamentally incompatible with the physician’s role as healer" and because it would be "difficult or impossible to control, and would pose serious societal risks". [22]

Hippocratic Oath[]

Some doctors[23] remind that physician-assisted suicide is contrary to the Hippocratic Oath, which is the oath historically taken by physicians. It states "I will not give a lethal drug to anyone if I am asked, nor will I advise such a plan.".[24][25] The original oath however has been modified many times and, contrary to popular belief, is not required by most modern medical schools, nor confers any legal obligations on individuals who choose to take it.[26] There are also procedures forbidden by the Hippocratic Oath which are in common practice today, such as abortion.[27]

Declaration of Geneva[]

The Declaration of Geneva is a revision of the Hippocratic Oath, first drafted in 1948 by the World Medical Association in response to forced (involuntary) euthanasia, eugenics and other medical crimes performed in Nazi Germany. It contains, "I will maintain the utmost respect for human life."[28]

International Code of Medical Ethics[]

The International Code of Medical Ethics, last revised in 2006, includes "A physician shall always bear in mind the obligation to respect human life" in the section "Duties of physicians to patients".[29]

Statement of Marbella[]

The Statement of Marbella was adopted by the 44th World Medical Assembly in Marbella, Spain, in 1992. It provides that "physician-assisted suicide, like voluntary euthanasia, is unethical and must be condemned by the medical profession."[30]

Concerns of expansion to people with chronic disorders[]

A concern present among health care professionals who are opposed to PAS, are the detrimental effects that the procedure can have with regard to vulnerable populations. This argument is known as the "slippery slope".[31] This argument encompasses the apprehension that once PAS is initiated for the terminally ill it will progress to other vulnerable communities, namely the disabled, and may begin to be used by those who feel less worthy based on their demographic or socioeconomic status. In addition, vulnerable populations are more at risk of untimely deaths because, "patients might be subjected to PAS without their genuine consent".[32]

Religious stances[]

Catholicism[]

The Roman Catholic Church acknowledges the fact that moral decisions regarding a person's life must be made according to one's own conscience and faith.[33] Catholic tradition has said that one's concern for the suffering of another is not a sufficient reason to decide whether it is appropriate to act upon voluntary euthanasia. According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, "God is the creator and author of all life." In this belief system God created human life, therefore God is the judge of when to end life.[33] From the Roman Catholic Church's perspective, deliberately ending one's life or the life of another is morally wrong and defies the Catholic doctrine. Furthermore, ending one's life deprives that person and his or her loved ones of the time left in life and causes grief and sorrow for those left behind.[34]

Pope Francis[35] is the current dominant figure of the Catholic Church. He affirms that death is a glorious event and should not be decided for by anyone other than God. Pope Francis insinuates that defending life means defending its sacredness.[36] The Roman Catholic Church teaches its followers that the act of euthanasia is unacceptable because it is perceived as a sin, as it goes against the Ten Commandments, "Thou shalt not kill. (You shall not kill)" As implied by the fifth commandment, the act of assisted suicide contradicts the dignity of human life as well as the respect one has for God.[37]

[34] Additionally, the Roman Catholic Church recommends that terminally ill patients should receive palliative care, which deals with physical pain while treating psychological and spiritual suffering as well, instead of physician-assisted suicide.[38]

Judaism[]

While preservation of life is one of the greatest values in Judaism, there are instances of suicide and assisted suicide appearing in the Bible and Rabbinic literature.[39] The medieval authorities debate the legitimacy of those measures and in what limited circumstances they might apply. The conclusion of the majority of later rabbinic authorities, and accepted normative practice within Judaism, is that suicide and assisted suicide can not be sanctioned even for a terminal patient in intractable pain.[40]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints[]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) is against euthanasia. Anyone who takes part in euthanasia, including "assisted suicide", is regarded as having violated the commandments of God.[41] However the church recognizes that when a person is in the final stages of terminal illness there may be difficult decisions to be taken. The church states that 'When dying becomes inevitable, death should be looked upon as a blessing and a purposeful part of an eternal existence. Members should not feel obligated to extend mortal life by means that are unreasonable.[42]

Neutrality[]

There have been calls for organisations representing medical professionals to take a neutral stance on assisted dying, rather than a position of opposition. The reasoning is that this would better reflect the views of medical professionals and that of wider society, and prevent those bodies from exerting undue influence over the debate.[43][44][45]

The UK Royal College of Nursing voted in July 2009 to move to a neutral position on assisted dying.[46]

The California Medical Association dropped its long-standing opposition in 2015 during the debate over whether an assisted dying bill should be introduced there, prompted in part by cancer sufferer Brittany Maynard.[47] The California End of Life Option Act was signed into law later that year.

In December 2017, the Massachusetts Medical Society (MMS) voted to repeal their opposition to physician-assisted suicide and adopt a position of neutrality.[48]

In October 2018, the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) voted to adopt a position of neutrality from one of opposition. This is contrary to the position taken by the American Medical Association (AMA), who oppose it.[49]

In January 2019 the British Royal College of Physicians announced it would adopt a position of neutrality until two-thirds of its members thinks it should either support or oppose the legalisation of assisted dying.[50]

Attitudes of healthcare professionals[]

It is widely believed that physicians should play a significant role, usually expressed as "gatekeeper", in the process of assisted suicide and voluntary euthanasia (as evident in the name "physician-assisted suicide"), often putting them at the forefront of the issue. Decades of opinion research shows that physicians in the US and several European countries are less supportive of legalization of PAS than the general public.[51] In the US, although "about two-thirds of the American public since the 1970s" have supported legalization, surveys of physicians "rarely show as much as half supporting a move".[51] However, physician and other healthcare professional opinions vary widely on the issue of physician-assisted suicide, as shown in the following tables.

| Study | Population | Willing to Assist PAS | Not Willing to Assist PAS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canadian Medical Association, 2011[52] | Canadian Medical Association (n=2,125) | 16% | 44% | ||

| Cohen, 1994 (NEJM)[53] | Washington state doctors (n=938) | 40% | 49% | ||

| Lee, 1996 (NEJM)[54] | Oregon state doctors (n=2,761) | 46% | 31% | ||

| Study | Population | In favor of PAS being legal | Not in favor of PAS being legal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medscape Ethics Report, 2014[55] | U.S.-based doctors | 54% | 31% | ||

| Seale, 2009[51] | United Kingdom physicians (n=3,733) | 35% | 62.2% | ||

| Cohen, 1994 (NEJM)[53] | Washington state doctors (n=938) | 53% | 39% | ||

Attitudes toward PAS vary by health profession as well; an extensive survey of 3733 medical physicians was sponsored by the National Council for Palliative Care, Age Concern, Help the Hospices, Macmillan Cancer Support, the Motor Neurone Disease Association, the MS Society and Sue Ryder Care showed that opposition to voluntary euthanasia and PAS was highest among Palliative Care and Care of the Elderly specialists, with more than 90% of palliative care specialists against a change in the law.[51]

In a 1997 study by Glasgow University's Institute of Law & Ethics in Medicine found pharmacists (72%) and anaesthetists (56%) to be generally in favor of legalizing PAS. Pharmacists were twice as likely as medical GPs to endorse the view that "if a patient has decided to end their own life then doctors should be allowed in law to assist".[56] A report published in January 2017 by NPR suggests that the thoroughness of protections that allow physicians to refrain from participating in the municipalities that legalized assisted suicide within the United States presently creates a lack of access by those who would otherwise be eligible for the practice.[57]

A poll in the United Kingdom showed that 54% of General Practitioners are either supportive or neutral towards the introduction of assisted dying laws.[58] A similar poll on Doctors.net.uk published in the BMJ said that 55% of doctors would support it.[59] In contrast the BMA, which represents doctors in the UK, opposes it.[60]

An anonymous, confidential postal survey of all General Practitioners in Northern Ireland, conducted in the year 2000, found that over 70% of responding GPs were opposed to physician-assisted suicide and voluntary active euthanasia.[61]

Legality[]

Physician-assisted suicide is legal in some countries, under certain circumstances, including Belgium, Canada, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Spain, Switzerland, and parts of the United States (California, Colorado, Hawaii, Maine, Montana,[note 1][62] New Jersey, New Mexico, Oregon, Vermont, Washington, and Washington DC )[63] and Australia (Tasmania, Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia). The Constitutional Courts of Austria, Colombia, Germany and Italy legalized assisted suicide, but their governments have not legislated or regulated the practice yet. New Zealand legalized assisted suicide in a referendum in 2020, but it will come into force on 6 November 2021. The parliament of Portugal passed the legalization of assisted suicide, but is now under consideration of the Constitutional Court.

Australia[]

Laws regarding assisted suicide in Australia are a matter for state governments, and in the case of the territories, the federal government. Physician-assisted suicide is currently legal in the state of Victoria,[64] Western Australia[65] and Tasmania.[66] In all other states and territories it remains illegal.

Under Victorian law, patients can ask medical practitioners regarding voluntary assisted dying, and doctors, including conscientious objectors, should refer to appropriately trained colleagues who do not conscientiously object.[67] Health practitioners are restricted from initiating conversation or suggesting voluntary assisted dying to a patient unprompted.

Voluntary euthanasia was legal in the Northern Territory for a short time under the Rights of the Terminally Ill Act 1995, until this law was overturned by the Federal Government who also removed the ability for territories to pass legislation relating to assisted dying. The highly controversial 'Euthanasia Machine', the first invented voluntary assisted dying machine of its kind, created by Philip Nitschke, utilised during this period is presently held at London's Science Museum.[68]

Austria[]

In December 2020, the Austrian Constitutional Court ruled that the prohibition of assisted suicide was unconstitutional.[69]

Belgium[]

The Euthanasia Act legalized voluntary euthanasia in Belgium in 2002,[70][71] but it did not cover physician-assisted suicide.[72]

Canada[]

Suicide was considered a criminal offence in Canada until 1972. Physician-assisted suicide has been legal in the Province of Quebec since 5 June 2014.[73] It was declared legal across the country through the Supreme Court of Canada decision Carter v. Canada (Attorney General) of 6 February 2015.[74] After a lengthy delay, the House of Commons passed a Bill[75] in mid-June 2016 that allows for physician-assisted suicide. Between 10 December 2015 and 30 June 2017, 2,149 medically assisted deaths were documented in Canada. Research published by Health Canada illustrates physician preference for physician-administered voluntary euthanasia, citing concerns of effective administration and prevention of the potential complications of self-administration by patients.[76]

China[]

In China, assisted suicide is illegal under Articles 232 and 233 of the Criminal Law of the People's Republic of China.[77] In China, suicide or neglect is considered homicide and can be punished by three to seven years in prison.[78] In May 2011, Zhong Yichun, a farmer, was sentenced two years' imprisonment by the People's Court of Longnan County, in China's Jiangxi Province for assisting Zeng Qianxiang to commit suicide. Zeng suffered from mental illness and repeatedly asked Zhong to help him commit suicide. In October 2010, Zeng took excessive sleeping pills and lay in a cave. As planned, Zhong called him 15 minutes later to confirm that he was dead and buried him. However, according to the autopsy report, the cause of death was from suffocation, not an overdose. Zhong was convicted of criminal negligence. In August 2011, Zhong appealed the court sentence, but it was rejected.[78]

In 1992, a physician was accused of murdering a patient with advanced cancer by lethal injection. He was eventually acquitted.[78]

Colombia[]

In May 1997 the Colombian Constitutional Court allowed for the voluntary euthanasia of sick patients who requested to end their lives, by passing Article 326 of the 1980 Penal Code.[79] This ruling owes its success to the efforts of a group that strongly opposed voluntary euthanasia. When one of its members brought a lawsuit to the Colombian Supreme Court against it, the court issued a 6 to 3 decision that "spelled out the rights of a terminally ill person to engage in voluntary euthanasia".[80]

Denmark[]

Assisted suicide is illegal in Denmark. Passive euthanasia, or the refusal to accept treatment, is not illegal. One survey found that 71% of Denmark's population was in favor of legalizing voluntary euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide.[81]

France[]

Assisted suicide is not legal in France. The controversy over legalising voluntary euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide is not as big as in the United States because of the country's "well developed hospice care programme".[82] However, in 2000 the controversy over the topic was ignited with Vincent Humbert. After a car crash that left him "unable to 'walk, see, speak, smell or taste'", he used the movement of his right thumb to write a book, I Ask the Right to Die (Je vous demande le droit de mourir) in which he voiced his desire to "die legally".[82] After his appeal was denied, his mother assisted in killing him by injecting him with an overdose of barbiturates that put him into a coma, killing him two days later. Though his mother was arrested for aiding in her son's death and later acquitted, the case did jump-start new legislation which states that when medicine serves "no other purpose than the artificial support of life" it can be "suspended or not undertaken".[83]

Germany[]

Killing somebody in accordance with their demands is always illegal under the German criminal code (Paragraph 216, "Killing at the request of the victim; mercy killing").[84]

Assisting suicide is generally legal and the Federal Constitutional Court has ruled that it is generally protected under the Basic Law; in 2020, it overturned a ban on commercialization of assisted suicide.[69] Since suicide itself is legal, assistance or encouragement is not punishable by the usual legal mechanisms dealing with complicity and incitement (German criminal law follows the idea of "accessories of complicity" which states that "the motives of a person who incites another person to commit suicide, or who assists in its commission, are irrelevant").[85]

There can however be legal repercussions under certain conditions for a number of reasons. Aside from laws regulating firearms, the trade and handling of controlled substances and the like (e.g. when acquiring poison for the suicidal person), this concerns three points:

Free vs. manipulated will[]

If the suicidal person is not acting out of his own free will, then assistance is punishable by any of a number of homicide offences that the criminal code provides for, as having "acted through another person" (§25, section 1 of the German criminal code,[86] usually called "mittelbare Täterschaft"). Action out of free will is not ruled out by the decision to end one's life in itself; it can be assumed as long as a suicidal person "decides on his own fate up to the end [...] and is in control of the situation".[85]

Free will cannot be assumed, however, if someone is manipulated or deceived. A classic textbook example for this, in German law, is the so-called Sirius case on which the Federal Court of Justice ruled in 1983: The accused had convinced an acquaintance that she would be reincarnated into a better life if she killed herself. She unsuccessfully attempted suicide, leading the accused to be charged with, and eventually convicted of attempted murder.[87] (The accused had also convinced the acquaintance that he hailed from the star Sirius, hence the name of the case).

Apart from manipulation, the criminal code states three conditions under which a person is not acting under his own free will:

- if the person is under 14

- if the person has "one of the mental diseases listed in §20 of the German Criminal Code"[85]

- a person that is acting under a state of emergency.

Under these circumstances, even if colloquially speaking one might say a person is acting of his own free will, a conviction of murder is possible.

Neglected duty to rescue[]

German criminal law obliges everybody to come to the rescue of others in an emergency, within certain limits (§323c of the German criminal code, "Omission to effect an easy rescue").[88] This is also known as a duty to rescue in English. Under this rule, the party assisting in the suicide can be convicted if, in finding the suicidal person in a state of unconsciousness, they do not do everything in their power to revive the subject.[85] In other words, if someone assists a person in committing suicide, leaves, but comes back and finds the person unconscious, they must try to revive them.[85]

This reasoning is disputed by legal scholars, citing that a life-threatening condition that is part, so to speak, of a suicide underway, is not an emergency. For those who would rely on that defence, the Federal Court of Justice has considered it an emergency in the past.

Homicide by omission[]

German law puts certain people in the position of a warrantor (Garantenstellung) for the well-being of another, e.g. parents, spouses, doctors and police officers. Such people might find themselves legally bound to do what they can to prevent a suicide; if they do not, they are guilty of homicide by omission.

Travel to Switzerland[]

Between 1998 and 2018 around 1250 German citizens (almost three times the number of any other nationality) travelled to Dignitas in Zurich, Switzerland for an assisted suicide, where this has been legal since 1918.[89][90] Switzerland being one of the few countries that permits assisted suicide for non-resident foreigners.[91]

Physician-assisted suicide[]

Physician-assisted suicide was formally legalised on 26 February 2020 when Germany's top court removed the prohibition of "professionally assisted suicide".[92]

Iceland[]

Assisted suicide is illegal.[93]

Ireland[]

Assisted suicide is illegal. "Both euthanasia and assisted suicide are illegal under Irish law. Depending on the circumstances, euthanasia is regarded as either manslaughter or murder and is punishable by up to life imprisonment."[94]

Luxembourg[]

After again failing to get royal assent for legalizing voluntary euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide, in December 2008 Luxembourg's parliament amended the country's constitution to take this power away from the monarch, the Grand Duke of Luxembourg.[95] Voluntary euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide were legalized in the country in April 2009.[96]

Netherlands[]

The Netherlands was the first country in the world to formally legalise voluntary euthanasia.[97] Physician-assisted suicide is legal under the same conditions as voluntary euthanasia. Physician-assisted suicide became allowed under the Act of 2001 which states the specific procedures and requirements needed in order to provide such assistance. Assisted suicide in the Netherlands follows a medical model which means that only doctors of patients who are suffering "unbearably without hope"[98] are allowed to grant a request for an assisted suicide. The Netherlands allows people over the age of 12 to pursue an assisted suicide when deemed necessary.

New Zealand[]

Assisted suicide was decriminalised after a binding referendum on New Zealand's . However, the legislation provides a year long delay before it takes effect on 6 November 2021. Under Section 179 of the Crimes Act 1961, it is illegal to 'aid and abet suicide' and this will remain the case outside the framework established under the End of Life Choices Act.

Norway[]

Assisted suicide is illegal in Norway. It is considered as murder, and is punishable by up to 21 years imprisonment.

South Africa[]

South Africa is struggling with the debate over legalizing voluntary euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Owing to the underdeveloped health care system that pervades the majority of the country, Willem Landman, "a member of the South African Law Commission, at a symposium on euthanasia at the World Congress of Family Doctors" stated that many South African doctors would be willing to perform acts of voluntary euthanasia when it became legalized in the country.[99] He feels that because of the lack of doctors in the country, "[legalizing] euthanasia in South Africa would be premature and difficult to put into practice [...]".[99]

On 30 April 2015 the High Court in Pretoria granted Advocate Robin Stransham-Ford an order that would allow a doctor to assist him in taking his own life without the threat of prosecution. On 6 December 2016 the Supreme Court of Appeal overturned the High Court ruling.[100]

Switzerland[]

Though it is illegal to assist a patient in dying in some circumstances, there are others where there is no offence committed.[101] The relevant provision of the Swiss Criminal Code[102] refers to "a person who, for selfish reasons, incites someone to commit suicide or who assists that person in doing so will, if the suicide was carried out or attempted, be sentenced to a term of imprisonment (Zuchthaus) of up to 5 years or a term of imprisonment (Gefängnis)."

A person brought to court on a charge could presumably avoid conviction by proving that they were "motivated by the good intentions of bringing about a requested death for the purposes of relieving "suffering" rather than for "selfish" reasons.[103] In order to avoid conviction, the person has to prove that the deceased knew what he or she was doing, had capacity to make the decision, and had made an "earnest" request, meaning they asked for death several times. The person helping also has to avoid actually doing the act that leads to death, lest they be convicted under Article 114: Killing on request (Tötung auf Verlangen) - A person who, for decent reasons, especially compassion, kills a person on the basis of his or her serious and insistent request, will be sentenced to a term of imprisonment (Gefängnis). For instance, it should be the suicide subject who actually presses the syringe or takes the pill, after the helper had prepared the setup.[104] This way the country can criminalise certain controversial acts, which many of its people would oppose, while legalising a narrow range of assistive acts for some of those seeking help to end their lives.

Switzerland is one of only a handful of countries in the world which permits assisted suicide for non-resident foreigners,[91] causing what some critics have described as suicide tourism. Between 1998 and 2018 around 1'250 German citizens (almost three times the number of any other nationality) travelled to Dignitas in Zurich, Switzerland for an assisted suicide. During the same period over 400 British citizens also opted to end their life at the same clinic.[89][90]

In May 2011, Zurich held a referendum that asked voters whether (i) assisted suicide should be prohibited outright; and (ii) whether Dignitas and other assisted suicide providers should not admit overseas users. Zurich voters heavily rejected both bans, despite anti-euthanasia lobbying from two Swiss social conservative political parties, the Evangelical People's Party of Switzerland and Federal Democratic Union. The outright ban proposal was rejected by 84% of voters, while 78% voted to keep services open should overseas users require them.[105]

In Switzerland non-physician-assisted suicide is legal, the assistance mostly being provided by volunteers, whereas in Belgium and the Netherlands, a physician must be present. In Switzerland, the doctors are primarily there to assess the patient's decision capacity and prescribe the lethal drugs. Additionally, unlike cases in the United States, a person is not required to have a terminal illness but only the capacity to make decisions. About 25% of people in Switzerland who take advantage of assisted suicide do not have a terminal illness but are simply old or "tired of life".[106]

Publicized cases[]

In January 2006 British doctor Anne Turner took her own life in a Zurich clinic having developed an incurable degenerative disease. Her story was reported by the BBC and later, in 2009, made into a TV film A Short Stay in Switzerland starring Julie Walters.

In July 2009, British conductor Sir Edward Downes and his wife Joan died together at a suicide clinic outside Zürich "under circumstances of their own choosing". Sir Edward was not terminally ill, but his wife was diagnosed with rapidly developing cancer.[107]

In March 2010, the American PBS TV program Frontline showed a documentary called The Suicide Tourist which told the story of Professor Craig Ewert, his family, and Dignitas, and their decision to commit assisted suicide using sodium pentobarbital in Switzerland after he was diagnosed and suffering with ALS (Lou Gehrig's disease).[108]

In June 2011, the BBC televised the assisted suicide of Peter Smedley, a canning factory owner, who was suffering from motor neurone disease. The programme – Sir Terry Pratchett's Choosing To Die – told the story of Smedley's journey to the end where he used The Dignitas Clinic, a voluntary euthanasia clinic in Switzerland, to assist him in carrying out his suicide. The programme shows Smedley eating chocolates to counter the unpalatable taste of the liquid he drinks to end his life. Moments after drinking the liquid, Smedley begged for water, gasped for breath and became red, he then fell into a deep sleep where he snored heavily while holding his wife's hand. Minutes later, Smedley stopped breathing and his heart stopped beating.

Uruguay[]

Assisted suicide, while criminal, does not appear to have caused any convictions, as article 37 of the Penal Code (effective 1934) states: "The judges are authorized to forego punishment of a person whose previous life has been honorable where he commits a homicide motivated by compassion, induced by repeated requests of the victim."[109]

United Kingdom[]

England and Wales[]

Deliberately assisting a suicide is illegal.[110] Between 2003 and 2006 Lord Joffe made four attempts to introduce bills that would have legalised physician-assisted suicide in England & Wales—all were rejected by the UK Parliament.[111] In the meantime the Director of Public Prosecutions has clarified the criteria under which an individual will be prosecuted in England and Wales for assisting in another person's suicide.[112] These have not been tested by an appellate court as yet[113] In 2014 Lord Falconer of Thoroton tabled an Assisted Dying Bill in the House of Lords which passed its Second Reading but ran out of time before the General Election. During its passage peers voted down two amendments which were proposed by opponents of the Bill. In 2015 Labour MP Rob Marris introduced another Bill, based on the Falconer proposals, in the House of Commons. The Second Reading was the first time the House was able to vote on the issue since 1997. A Populus poll had found that 82% of the British public agreed with the proposals of Lord Falconer's Assisted Dying Bill.[114] However, in a free vote on 11 September 2015, only 118 MPs were in favour and 330 against, thus defeating the bill.[115]

Scotland[]

Unlike the other jurisdictions in the United Kingdom, suicide was not illegal in Scotland before 1961 (and still is not) thus no associated offences were created in imitation. Depending on the actual nature of any assistance given to a suicide, the offences of murder or culpable homicide might be committed or there might be no offence at all; the nearest modern prosecutions bearing comparison might be those where a culpable homicide conviction has been obtained when drug addicts have died unintentionally after being given "hands on" non-medical assistance with an injection. Modern law regarding the assistance of someone who intends to die has a lack of certainty as well as a lack of relevant case law; this has led to attempts to introduce statutes providing more certainty.

Independent MSP Margo MacDonald's "End of Life Assistance Bill" was brought before the Scottish Parliament to permit physician-assisted suicide in January 2010. The Catholic Church and the Church of Scotland, the largest denomination in Scotland, opposed the bill. The bill was rejected by a vote of 85–16 (with 2 abstentions) in December 2010.[116][117]

The Assisted Suicide (Scotland) Bill was introduced on 13 November 2013 by the late Margo MacDonald MSP and was taken up by Patrick Harvie MSP on Ms MacDonald's death. The Bill entered the main committee scrutiny stage in January 2015 and reached a vote in Parliament several months later; however the bill was again rejected.

Northern Ireland[]

Health is a devolved matter in the United Kingdom and as such it would be for the Northern Ireland Assembly to legislate for assisted dying as it sees fit. As of 2018, there has been no such bill tabled in the Assembly.

Assisted Dying Coalition[]

A coalition of assisted dying organizations working in favour of legal recognition of the right to die was formed in early 2019.[118]

United States[]

1 In some states assisted suicide is protected through court ruling even though specific legislation allowing it does not exist.

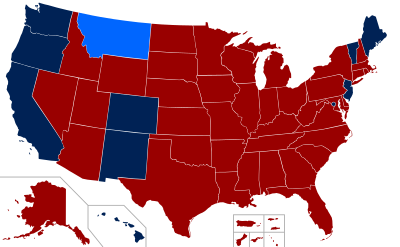

Assisted death is legal in the American states of California (via the California End of Life Option Act of 2015, enacted June 2016),[119] Colorado (End of Life Options Act of 2016), Hawaii (Death with Dignity Act of 2018), Oregon (via the Oregon Death with Dignity Act, 1994),[120] Washington (Washington Death with Dignity Act of 2008), Washington DC (District of Columbia Death with Dignity Act of 2016), New Jersey (New Jersey Dignity in Dying Bill of Rights Act of 2019), New Mexico (Elizabeth Whitefield End-of-Life Options Act, 2021), Maine[121] (eff. 1 January 2020 - Maine Death with Dignity Act of 2019) and Vermont (Patient Choice and Control at End of Life Act of 2013). In Montana, the Montana Supreme Court ruled in Baxter v. Montana (2009) that it found no law or public policy reason that would prohibit physician-assisted dying.[62] Oregon and Washington specify some restrictions. It was briefly legal in New Mexico from 2014 due to a court decision, but this verdict was overturned in 2015. New Mexico is the most recent state to legalize physician-assisted suicide, with the Elizabeth Whitefield End-of-Life Options Act being signed by Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham on April 8, 2021, and scheduled to go into effect on June 18, 2021.

Oregon requires a physician to prescribe drugs and they must be self-administered. In order to be eligible, the patient must be diagnosed by an attending physician as well as by a consulting physician, with a terminal illness that will cause the death of the individual within six months. The law states that, in order to participate, a patient must be: 1) 18 years of age or older, 2) a resident of Oregon, 3) capable of making and communicating health care decisions for him/herself, and 4) diagnosed with a terminal illness that will lead to death within six months. It is up to the attending physician to determine whether these criteria have been met.[122] It is required the patient orally request the medication at least twice and contribute at least one (1) written request. The physician must notify the patient of alternatives; such as palliative care, hospice and pain management. Lastly the physician is to request but not require the patient to notify their next of kin that they are requesting a prescription for a lethal dose of medication. Assuming all guidelines are met and the patient is deemed competent and completely sure they wish to end their life, the physician will prescribe the drugs.[123]

The law was passed in 1997. As of 2013, a total of 1,173 people had DWDA prescriptions written and 752 patients had died from ingesting drugs prescribed under the DWDA.[124] In 2013, there were approximately 22 assisted deaths per 10,000 total deaths in Oregon.[124]

Washington's rules and restrictions are similar, if not exactly the same, as Oregon's. Not only does the patient have to meet the above criteria, they also have to be examined by not one, but two doctors licensed in their state of residence. Both doctors must come to the same conclusion about the patient's prognosis. If one doctor does not see the patient fit for the prescription, then the patient must undergo psychological inspection to tell whether or not the patient is in fact capable and mentally fit to make the decision of assisted death or not.[123]

In May 2013, Vermont became the fourth state in the union to legalize medical aid-in-dying. Vermont's House of Representatives voted 75–65 to approve the bill, Patient Choice and Control at End of Life Act. This bill states that the qualifying patient must be at least 18, a Vermont resident and suffering from an incurable and irreversible disease, with less than six months to live. Also, two physicians, including the prescribing doctor must make the medical determination.[125]

In January 2014, it seemed as though New Mexico had inched closer to being the fifth state in the United States to legalize physician-assisted suicide via a court ruling.[126] "This court cannot envision a right more fundamental, more private or more integral to the liberty, safety and happiness of a New Mexican than the right of a competent, terminally ill patient to choose aid in dying," wrote Judge Nan G. Nash of the Second District Court in Albuquerque. The NM attorney general's office said it was studying the decision and whether to appeal to the State Supreme Court. However, this was overturned on 11 August 2015 by the New Mexico Court of Appeals, in a 2-1 ruling, that overturned the Bernalillo County District Court Ruling. The Court gave the verdict: "We conclude that aid in dying is not a fundamental liberty interest under the New Mexico Constitution".[127] On April 8, 2021, the Governor of New Mexico signed the Elizabeth Whitefield End-of-Life Options Act, legalizing assisted suicide in the state. The law is set to take effect on June 18, 2021.[128]

In November 2016, the citizens of Colorado approved Proposition 106, the Colorado End of Life Options Act, with 65% in favor. This made it the third state to legalize medical aid-in-dying by a vote of the people, raising the total to six states.

The punishment for participating in physician-assisted death (PAD) varies throughout many states. The state of Wyoming does not "recognize common law crimes and does not have a statute specifically prohibiting physician-assisted suicide". In Florida, "every person deliberately assisting another in the commission of self-murder shall be guilty of manslaughter, a felony of the second degree".[129]

States currently considering physician-assisted suicide laws[citation needed] Arizona, Connecticut, Indiana, New York, and Virginia.

Washington vs. Glucksberg[relevant?]

In Washington, physician-assisted suicide did not become legal until 2008.[130] In 1997, four Washington physicians and three terminally ill patients brought forth a lawsuit that would challenge the ban on medical aid in dying that was in place at the time. This lawsuit was first part of a district court hearing, where it ruled in favor of Glucksberg,[131] which was the group of physicians and terminally ill patients. The lawsuit was then affirmed by the Ninth Circuit.[132] Thus, it was taken to the Supreme Court, and there the Supreme Court decided to grant Washington certiorari. Eventually, the Supreme Court decided, with a unanimous vote, that medical aid in dying was not a protected right under the constitution as of the time of this case.[133]

Brittany Maynard[]

A highly publicized case in the United States was the death of Brittany Maynard in 2014. After being diagnosed with terminal brain cancer, Maynard decided that instead of suffering with the side effects the cancer would bring, she wanted to choose when she would die. She was residing in California when she was diagnosed, where assisted death was not legal. She and her husband moved to Oregon where assisted death was legal, so she could take advantage of the program. Before her death, she started the Brittany Maynard fund, which works to legalize the choice of ending one's life in cases of a terminal illness. Her public advocacy motivated her family to continue to try and get assisted death laws passed in all 50 states.[134]

See also[]

- Betty and George Coumbias

- Bioethics

- Consensual homicide

- Euthanasia device

- Legality of euthanasia

- Jack Kevorkian

- Right to Die? (2008 film)

- Brittany Maynard

- Philip Nitschke

- Senicide

- You don't know Jack (2010, film)

- Voluntary Assisted Dying Act 2017 (Victoria)

- Suicide by cop

- A Short Stay in Switzerland (2009 film)

Notes[]

- ^ See Baxter v. Montana

References[]

- ^ Davis, Nicola (15 July 2019). "Euthanasia and assisted dying rates are soaring. But where are they legal?". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ Patients Rights Council (6 January 2017). "Assisted Suicide Laws in the United States". Archived from the original on 11 September 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^ Hedberg, M.D., MPH., Katrina (6 March 2003). "Five Years of Legal Physician-Assisted Suicide in Oregon". New England Journal of Medicine. 348 (10): 961–964. doi:10.1056/NEJM200303063481022. PMID 12621146.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ "EUTHANASIA AND ASSISTED SUICIDE (UPDATE 2007)" (PDF). Canadian Medical Association. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2011.

- ^ "What are euthanasia and assisted suicide?". Medical News Today. Medical News Today. 17 December 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ "Suicidism". Webster's 1913 Dictionary. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Baril, Alexandre (2020). "Suicidism: A new theoretical framework to conceptualize suicide from an anti-oppressive perspective". Disability Studies Quarterly. 40 (3): 1–41. doi:10.18061/dsq.v40i3.7053.

- ^ "ASSISTED DYING NOT ASSISTED SUICIDE". Dignity in Dying. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ^ "Why medically assisted dying is not suicide". Dying with Dignity Canada. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Baril, Alexandre (2017). "The Somatechnologies of Canada's Medical Assistance in Dying Law: LGBTQ Discourses on Suicide and the Injunction to Live". Somatechnics. 7 (2): 201–217. doi:10.3366/soma.2017.0218.

- ^ Grace, Wedlake (2020). "Complicating Theory through Practice: Affirming the Right to Die for Suicidal People". Canadian Journal of Disability Studies. 9 (4): 89–110. doi:10.15353/cjds.v9i4.670.

- ^ Starks, PhD., MPH., Helene. "Physician Aid-in-Dying". Physician Aid-in-Dying: Ethics in Medicine. University of Washington School of Medicine. Retrieved 29 April 2019.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Emanuel, Ezekiel J.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, Bregje D.; Urwin, John W.; Cohen, Joachim (5 July 2016). "Attitudes and Practices of Euthanasia and Physician-Assisted Suicide in the United States, Canada, and Europe". JAMA. 316 (1): 79–90. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.8499. PMID 27380345.

- ^ "OREGON DEATH WITH DIGNITY ACT: 2015 DATA SUMMARY" (PDF). Oregon.gov. Oregon Health Authority. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ Ganzini, Linda; Harvath, Theresa A.; Jackson, Ann; Goy, Elizabeth R.; Miller, Lois L.; Delorit, Molly A. (22 August 2002). "Experiences of Oregon Nurses and Social Workers with Hospice Patients Who Requested Assistance with Suicide". New England Journal of Medicine. 347 (8): 582–588. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa020562. PMID 12192019.

- ^ Wang, Shi-Yi; Aldridge, Melissa D.; Gross, Cary P.; Canavan, Maureen; Cherlin, Emily; Johnson-Hurzeler, Rosemary; Bradley, Elizabeth (September 2015). "Geographic Variation of Hospice Use Patterns at the End of Life". Journal of Palliative Medicine. 18 (9): 771–780. doi:10.1089/jpm.2014.0425. PMC 4696438. PMID 26172615.

- ^ "OREGON DEATH WITH DIGNITY ACT: 2015 DATA SUMMARY" (PDF). State of Oregon. Oregon Public Health Division. Retrieved 29 April 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Washington State Department of Health

- ^ "Living Well at the End of Life Poll" (PDF). The National Journal. February 2010. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ Ganzini, Linda; Goy, Elizabeth R.; Dobscha, Steven K.; Prigerson, Holly (December 2009). "Mental Health Outcomes of Family Members of Oregonians Who Request Physician Aid in Dying". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 38 (6): 807–815. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.04.026. PMID 19783401.

- ^ "The Right to Die with Dignity: 1988 General Resolution". Unitarian Universalist Association. 24 August 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ Lagay, F (1 January 2003). "Physician-Assisted Suicide: The Law and Professional Ethics". AMA Journal of Ethics. 5 (1). doi:10.1001/virtualmentor.2003.5.1.pfor1-0301. PMID 23267685.

- ^ Kass, Leon R. (1989). "Neither for love nor money: why doctors must not kill" (PDF). Public Interest. 94: 25–46. PMID 11651967.

- ^ "The Internet Classics Archive - The Oath by Hippocrates". mit.edu.

- ^ "Hippocratic oath". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "Greek Medicine - The Hippocratic Oath". History of Medicine. 7 February 2012.

- ^ Oxtoby, Kathy (14 December 2016). "Is the Hippocratic oath still relevant to practicing doctors today?". BMJ: i6629. doi:10.1136/bmj.i6629.

- ^ "WMA DECLARATION OF GENEVA". www.wma.net. 6 November 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ "WMA International Code of Medical Ethics". wma.net. 1 October 2006. Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ "WMA Statement on Physician-Assisted Suicide". wma.net. 1 May 2005. Archived from the original on 25 July 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- ^ Ross Douthat (6 September 2009). "A More Perfect Death". The New York Times.

- ^ Mayo, David J.; Gunderson, Martin (July 2002). "Vitalism Revitalized: Vulnerable Populations, Prejudice, and Physician-Assisted Death". The Hastings Center Report. 32 (4): 14–21. doi:10.2307/3528084. JSTOR 3528084. PMID 12362519.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Donovan, G. Kevin (1 December 1997). "Decisions at the End of Life: Catholic Tradition". Christian Bioethics. 3 (3): 188–203. doi:10.1093/cb/3.3.188. PMID 11655313.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Harvey, Kathryn (2016). "Mercy and Physician-Assisted Suicide" (PDF). Ethics & Medics. 41 (6): 1–2. doi:10.5840/em201641611.

- ^ "Pope Francis Biography".

- ^ Cherry, Mark J. (6 February 2015). "Pope Francis, Weak Theology, and the Subtle Transformation of Roman Catholic Bioethics". Christian Bioethics. 21 (1): 84–88. doi:10.1093/cb/cbu045.

- ^ "Roman Catholicism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ Yao, Teresa (2016). "Can We Limit a Right to Physician-Assisted Suicide?". The National Catholic Bioethics Quarterly. 16 (3): 385–392. doi:10.5840/ncbq201616336.

- ^ Samuel 1:31:4–5, Daat Zekeinim Baalei Hatosfot Genesis 9:5.

- ^ Steinberg, Dr. Abraham (1988). Encyclopedia Hilchatit Refuit. Jerusalem: Shaarei Zedek Hospital. p. Vol. 1 Pg. 15.

- ^ "Handbook 2: Administering the Church – 21.3 Medical and Health Policies". Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

- ^ "Euthanasia and Prolonging Life". LDS News.

- ^ Godlee, Fiona (8 February 2018). "Assisted dying: it's time to poll UK doctors". BMJ: k593. doi:10.1136/bmj.k593.

- ^ "'Neutrality' on assisted suicide is a step forward". Nursing Times. 31 July 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ Gerada, C. (2012). "The case for neutrality on assisted dying — a personal view". The British Journal of General Practice. 62 (605): 650. doi:10.3399/bjgp12X659376. PMC 3505400. PMID 23211247.

- ^ "RCN Position statement on assisted dying" (PDF). Royal College of Nursing.

- ^ "California Medical Association drops opposition to doctor-assisted suicide". Reuters. 20 May 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ^ "Massachusetts Medical Society adopts several organizational policies at Interim Meeting". Massachusetts Medical Society. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- ^ "COD Addresses Medical Aid in Dying, Institutional Racism". AAFP.

- ^ "Doctors to be asked if they would help terminally ill patients die". Chronicle Live. Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Seale C (April 2009). "Legalisation of euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide: survey of doctors' attitudes". Palliat Med. 23 (3): 205–12. doi:10.1177/0269216308102041. PMID 19318460. S2CID 43547476.

- ^ Canadian Medical Association (2011). "Physician view on end-of-life issues vary widely: CMA survey" (PDF). Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cohen, Jonathan (1994). "Attitudes toward Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia among Physicians in Washington State". The New England Journal of Medicine. 331 (2): 89–94. doi:10.1056/NEJM199407143310206. PMID 8208272.

- ^ Lee, Melinda (1996). "Legalizing Assisted Suicide — Views of Physicians in Oregon". New England Journal of Medicine. 334 (5): 310–15. doi:10.1056/nejm199602013340507. PMID 8532028.

- ^ Kane, MA, Leslie. "Medscape Ethics Report 2014, Part 1: Life, Death, and Pain". Medscape. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ McLean, S. (1997). Sometimes a Small Victory. Institute of Law and Ethics in Medicine, University of Glasgow.

- ^ "Legalizing Aid in Dying Doesn't Mean Patients Have Access To It". NPR. Retrieved 18 November 2017.

- ^ "Public Opinion - Dignity in Dying". Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ^ "Assisted dying case 'stronger than ever' with majority of doctors now in support". 7 February 2018. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ^ "Physician-assisted dying - BMA".

- ^ McGlade, K J; Slaney, L; Bunting, B P; Gallagher, A G (October 2000). "Voluntary euthanasia in Northern Ireland: general practitioners' beliefs, experiences, and actions". The British Journal of General Practice. 50 (459): 794–797. PMC 1313819. PMID 11127168.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Baxter v. State, 2009 MT 449, 224 P.3d 1211, 354 Mont. 234 (2009).

- ^ "D.C. physician-assisted suicide law goes into effect". The Washington Times. 18 February 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "Voluntary euthanasia is now legal in Victoria".

- ^ "Voluntary euthanasia becomes law in WA in emotional scenes at Parliament". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 10 December 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ^ "Tasmania passes voluntary assisted dying legislation, becoming third state to do so". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 23 March 2021.

- ^ "Health practitioner information on voluntary assisted dying".

- ^ "Euthanasia machine, Australia, 1995-1996".

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brade, Alexander; Friedrich, Roman (16 January 2021). "Stirb an einem anderen Tag". Verfassungsblog. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- ^ "Moniteur Belge - Belgisch Staatsblad". fgov.be.

- ^ "Moniteur Belge - Belgisch Staatsblad". fgov.be.

- ^ Adams, M.; Nys, H. (1 September 2003). "Comparative Reflections on the Belgian Euthanasia Act 2002". Medical Law Review. 11 (3): 353–376. doi:10.1093/medlaw/11.3.353. PMID 16733879.

- ^ Hamilton, Graeme (10 December 2015). "Is it euthanasia or assisted suicide? Quebec's end-of-life care law explained". National Post. Toronto, Ontario. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ Carter v. Canada (Attorney General), 2015 S.C.C. 5, [2015] 1 S.C.R. 331.

- ^ Bill C-14, An Act to amend the Criminal Code & to make related amendments to other Acts (medical assistance in dying), 1st Sess., 42nd Parl., 2015–2016 (assented to 2016‑06‑17), S.C. 2016, c. 3.

- ^ Health Canada (October 2017), Second Interim Report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada (PDF), Ottawa: Health Canada, ISBN 9780660204673, H14‑230/2‑2017E‑PDF.

- ^ "Euthanasia & Physician-Assisted Suicide (PAS) around the World - Euthanasia - ProCon.org". euthanasia.procon.org. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Zeldin, Wendy (17 August 2011). "China: Case of Assisted Suicide Stirs Euthanasia Debate". The Library of Congress.

- ^ McDougall & Gorman 2008

- ^ Whiting, Raymond (2002). A Natural Right to Die: Twenty-Three Centuries of Debate. Westport, Connecticut. pp. 41.

- ^ Nielsen, Morten Ebbe Juul; Andersen, Martin Marchman (27 May 2014). "Bioethics in Denmark" (PDF). Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics. 23 (3): 326–333. doi:10.1017/S0963180113000935. PMID 24867435.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McDougall & Gorman 2008, p. 84

- ^ McDougall & Gorman 2008, p. 86

- ^ "German Criminal Code". German Federal Ministry of Justice. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Wolfslast, Gabriele (2008). "Physician-Assisted Suicide and the German Criminal Law". Giving Death a Helping Hand. International Library of Ethics, Law, and the New Medicine. 38. pp. 87–95. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-6496-8_8. ISBN 978-1-4020-6495-1.

- ^ "German Criminal Code". German Federal Ministry of Justice. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ "BGH Urteil vom 05.07.1983 (1 StR 168/83)". ejura-examensexpress.de. Archived from the original on 24 February 2009. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ^ "German Criminal Code". German Federal Ministry of Justice. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Statistiken".[unreliable source?]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hurst, Samia A; Mauron, Alex (1 February 2003). "Assisted suicide and euthanasia in Switzerland: allowing a role for non-physicians". BMJ. 326 (7383): 271–273. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7383.271. PMC 1125125. PMID 12560284.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Assisted Suicide Laws Around the World - Assisted Suicide".

- ^ "Germany overturns ban on professionally assisted suicide". Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ^ "Iceland". alzheimer-europe.org.

- ^ "Ireland's Health Services - Ireland's Health Service". Ireland's Health Service. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ "Luxembourg strips monarch of legislative role". The Guardian. London. 12 December 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ "Luxembourg becomes third EU country to legalize euthanasia". Tehran Times. Archived from the original on 13 June 2011.

- ^ "Netherlands, first country to legalize euthanasia" (PDF). The World Health Organization. 2001.

- ^ "Euthanasia is legalised in Netherlands". The Independent. 11 April 2001.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McDougall & Gorman 2008, p. 80

- ^ "SCA overturns right-to-die ruling". News24. 6 December 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ Schwarzenegger, Christian; Summers, Sarah J. (3 February 2005). "Hearing with the Select Committee on the Assisted Dying for the Terminally Ill Bill" (PDF). House of Lords Hearings. Zürich: University of Zürich Faculty of Law. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 1 July 2009. (PDF)

- ^ "Inciting and assisting someone to commit suicide (Verleitung und Beihilfe zum Selbstmord)". Swiss Criminal Code (in German). Zürich: Süisse: Article 115. 23 June 1989.

- ^ Whiting, Raymond (2002). A Natural Right to Die: Twenty-Three Centuries of Debate. Westport, Connecticut. pp. 46.

- ^ Christian Schwarzenegger and Sarah Summers of the University of Zurich's Faculty of Law (3 February 2005). "Hearing with the Select Committee on the Assisted Dying for the Terminally Ill Bill" (PDF). House of Lords, Zurich. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 1 July 2009.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ "Swiss vote backs assisted suicide". BBC News. 15 May 2011.

- ^ Andorno, Roberto (30 April 2013). "Nonphysician-Assisted Suicide in Switzerland" (PDF). Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics. 22 (3): 246–253. doi:10.1017/S0963180113000054. PMID 23632255.

- ^ Lundin, Leigh (2 August 2009). "YOUthanasia". Criminal Brief. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ "The Suicide Tourist - FRONTLINE - PBS". pbs.org.

- ^ del Uruguay, Republica Oriental. "Penal Code of Uruguay". Parliament of Uruguay. Archived from the original on 30 July 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ Huxtable, RichardHuxtable, Richard (2007). Euthanasia, Ethics and the Law: From Conflict to Compromise. Abingdon, UK; New York: Routledge Cavendish. ISBN 9781844721061.

- ^ "Assisted Dying Bill - latest". BBC News Online.

- ^ "DPP publishes interim policy on prosecuting assisted suicide: The Crown Prosecution Service". cps.gov.uk. 23 September 2009. Archived from the original on 27 September 2009.

- ^ "A Critical Consideration of the Director of Public Prosecutions Guidelines in Relation to Assisted Suicide Prosecutions and their Application to the Law". halsburyslawexchange.co.uk. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ "Dignity in Dying Poll" (PDF). Populus. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 June 2015.

- ^ James Gallagher & Philippa Roxby (11 September 2015). "Assisted Dying Bill: MPs reject 'right to die' law". BBC News.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ "End of Life Assistance (Scotland) Bill (SP Bill 38)". The Scottish Parliament. 21 January 2010. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ "Margo MacDonald's End of Life Assistance Bill rejected". BBC News Online. 1 December 2010.

- ^ "About Us – Assisted Dying Coalition".

- ^ Lisa Aliferis (10 March 2016). "California To Permit Medically Assisted Suicide As of 9 June". NPR.

- ^ "Death With Dignity Act Legislative Statute". Archived from the original on 29 June 2009. Retrieved 2 July 2009.

- ^ "Maine". Death With Dignity. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions – About the Death With Dignity Act". Oregon Health Authority.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "State-by-State Guide to Physician-Assisted Suicide - Euthanasia - ProCon.org". procon.org.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Oregon Public Health Division – 2013 DWDA Report" (PDF). Oregon Health Authority. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ Sullivan, Nora. "Vermont Legislature Passes Assisted Suicide Bill." Charlotte Lozier Institute RSS. Charlotte Lozier Institute, 15 May 2013. Web. 4 December 2013.

- ^ "Morris v. Brandenberg". Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ Richardson, Valerie. "New Mexico court strikes down ruling that allowed assisted suicide". Washington Times. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ "New Mexico latest state to adopt medically assisted suicide". AP NEWS. 8 April 2021. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- ^ "Assisted Suicide Laws in the United States | Patients Rights Council". www.patientsrightscouncil.org. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ^ Health, Washington State Department of. "Death with Dignity Act :: Washington State Department of Health". www.doh.wa.gov. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ "Washington v. Glucksberg | Vacco v. Quill". www.adflegal.org. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ "Case Brief: Washington v. Glucksberg, 521 U.S. 702". www.studentjd.com. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ linderd. "Washington v Glucksberg". law2.umkc.edu. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ "The Brittany Fund | About". thebrittanyfund.org. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

External links[]

- Asch DA, DeKay ML (September 1997). "Euthanasia among US critical care nurses. Practices, attitudes, and social and professional correlates". Med Care. 35 (9): 890–900. doi:10.1097/00005650-199709000-00002. JSTOR 3767454. PMID 9298078.

- McDougall, Jennifer Fecio; Gorman, Martha (2008). Contemporary World Issues: Euthanasia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO.

- "What is Physician-Assisted Suicide?". Northwestern University. 17 July 2014. Archived from the original on 11 July 2006. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- "Who Has the Right to a Dignified Death? / The Death Treatment (When should people with a non-terminal illness be helped to die?) Letter from Belgium - RACHEL AVIV". New Yorker. 22 June 2015.

- "The Last Day of Her Life". The New York Times Magazine. 17 May 2015.

- Assisted suicide

- Disability rights

- Euthanasia

- Suicide methods