Australian Army during World War II

| Australian Army | |

|---|---|

Australian soldiers rest in the Finisterre Ranges of New Guinea while en route to the front line during March 1944 | |

| Active | 1939–1945 |

| Country | Australia |

| Allegiance | Allies |

| Type | Army |

| Size | 80,000 (September 1939) 476,000 (peak in 1942) 730,000 (total) |

| Engagements | World War II

|

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Thomas Blamey |

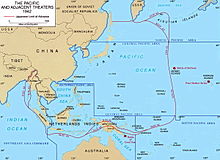

The Australian Army was the largest service in the Australian military during World War II. Prior to the outbreak of war the Australian Army was split into the small full-time Permanent Military Forces (PMF) and the larger part-time Militia. Following the outbreak of war, on 14 September 1939 Prime Minister Robert Menzies announced that 40,000 members of the Militia would be called up for training and a 20,000-strong expeditionary force, designated the Second Australian Imperial Force (Second AIF), would be formed for overseas service. Meanwhile, conscription was introduced in October 1939 to keep the Militia at strength as its members volunteered for the AIF. The Australian Army subsequently made an important contribution to the Allied campaigns in the Mediterranean, the Middle East and North Africa fighting the Germans, Italians and Vichy French during 1940 and 1941, and later in the jungles of the South West Pacific Area fighting the Japanese between late 1941 and 1945. Following the Japanese surrender Australian Army units were deployed as occupation forces across the South West Pacific. Meanwhile, the Army contributed troops to the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF) in Japan from 1946.

The Army was considerably expanded in early 1942 in response to the Japanese threat to Australia. During this year the Army's strength peaked at eleven infantry divisions and three armoured divisions, and in August 1942 the Army had a strength of 476,000 men. This force was larger than Australia's population and economy could sustain, and its strength was reduced in the second half of the year. Militia units were able to serve outside of Australian territory in the South West Pacific Area from January 1943 after the Defence (Citizen Military Forces) Act 1943 was passed, but few did so. The Army was further reduced by 100,000 members from October 1943 to free up manpower for industry. At the end of 1943 the Army's strength was set at six infantry divisions and two armoured brigades, although further reductions were ordered in August 1944 and June 1945. The Australian Army generally had a long-standing policy of using British-designed equipment, but equipment from Australia, the United States and some other countries was introduced into service in the war's later years. Pre-war doctrine was focused on conventional warfare in a European environment and the Army did not have any doctrine for jungle warfare prior to 1943. In early 1943 the Army developed a jungle warfare doctrine by adapting the pre-war field service regulations to meet the conditions in the South West Pacific.

The demands of combat during World War II led to changes in the composition of Army units. The success of German mechanised units during the invasions of Poland and France convinced Australian defence planners that the Army required armoured units, and these began to be raised in 1941. These units were not suitable for jungle warfare, however, and most were disbanded during 1943 and 1944. Conditions in the South West Pacific also led the Army to convert its six combat divisions to jungle divisions in early 1943 and 1944 with fewer heavy weapons and vehicles. This organisation proved only moderately successful, and the divisions were strengthened for their 1944–45 campaigns. The process of demobilisation began immediately after the end of hostilities in August 1945 and was finally completed on 15 February 1947. A total of 730,000 personnel enlisted in the Australian Army during the war, a figure which represented around 10 percent of the population. Nearly 400,000 men ultimately served overseas, with 40 percent of the total force serving in front line areas. As a proportion of its population, the Australian Army was ultimately one of the largest Allied armies during World War II. Casualties included 11,323 killed in action, 1,794 who died of wounds, and 21,853 wounded. Another 5,558 were killed or died as prisoners of war (POWs), while non-battle casualties in operational areas were also significant and included 1,088 killed and 33,196 wounded or injured. In addition, the Army suffered a substantial number of casualties in non-operational areas: 1,795 soldiers killed and 121,800 wounded or injured.

Background[]

Prior to the outbreak of war the Australian Army consisted of the small full-time Permanent Military Forces (PMF) and the larger part-time Militia. Throughout the inter-war years, a combination of complacency and economic austerity had resulted in limited defence spending.[1] In 1929, following the election of the Scullin Labor government, conscription was abolished and in its place a new system was introduced whereby the Militia would be maintained on a part-time, voluntary basis only.[2] The size of the Army remained small up until 1938 and 1939 when the Militia was rapidly expanded as the threat of war grew. In 1938, there had been only 35,000 soldiers in the Militia, but by September 1939 this had been increased to 80,000, supported by a PMF of 2,800 full-time soldiers whose main responsibility was largely to administer and train the Militia.[3] This expansion had little impact on improving the readiness of Australian forces upon the outbreak of the war,[4] though, as the provisions of the Defence Act 1903 restricted the pre-war Army to service in Australia and its territories including Papua and New Guinea. As a result, when Australia entered the war in 1939, a new all-volunteer force was required that could fight in Europe or elsewhere outside of Australia's immediate region. (Similarly, in World War I the all-volunteer First Australian Imperial Force (First AIF) was raised and served with distinction at Gallipoli, in the Middle East and on the Western Front.)[5]

From the 1920s Australia's defence thinking was dominated by the "Singapore strategy", which centred on the establishment of a major naval base at Singapore and the use of naval forces to respond to any future Japanese aggression in the region.[6] As a maritime strategy, it resulted in a defence budget that was focused on building up the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), in order to support the British Royal Navy. Between 1923 and 1929, £20,000,000 was spent on the RAN, while the Australian Army and the munitions industry received only £10,000,000 and the fledgling Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) just £2,400,000. The strategy met significant political opposition from sections of the regular Army, including several prominent officers such as Henry Wynter and John Lavarack.[7][8] Wynter in particular argued that war was most likely to break out in the Pacific at a time when Britain was involved in a crisis in Europe and would be unable to send sufficient resources to Singapore. He contended that Singapore was vulnerable, especially to attack from the land and the air, and argued for a more balanced policy of building up the Army and RAAF rather than relying on the RAN.[7]

During the 1930s the Australian Army's organisation, equipment and doctrine were similar to those of World War I. The Militia was organised into infantry and horse-mounted cavalry divisions with fixed coastal fortifications positioned at strategic ports. While the Army recognised that there was a threat of war with Japan, little had been done to prepare for jungle warfare as pre-war planning had conceptualised any such conflict as taking place in the main population centres of Australia's eastern seaboard, along with isolated attacks against strategic points in Western Australia.[10] The Army followed the trends in the British Army as it modernised in the late 1930s, but was unable to obtain the up-to-date equipment needed to properly implement the new British doctrines and organisations due to a lack of resources as a result of limited defence expenditures. Nevertheless, the Militia provided a pool of experienced officers and soldiers who could be used to expand the Army in the event of war,[11] and indeed during the course of the war about 200,000 Militia soldiers volunteered for overseas service.[12]

In 1942 the Army adopted the title Australian Military Forces (AMF) to encompass the various categories of service: AIF, Militia and Permanent Forces.[13] Wartime exigencies required a rapid expansion of the Army and during the war 730,000 personnel enlisted in either the Militia or the AIF, a figure which represented around 10 percent of Australia's population of just seven million,[3] one of the highest percentages of any of the Allied armies during World War II.[14] It subsequently made an important contribution to the Allied campaigns in the Mediterranean, the Middle East and North Africa fighting the Germans, Italians and Vichy French during 1940 and 1941 as part of British Commonwealth forces, and later in the jungles of the South West Pacific Area (SWPA) fighting the Japanese between late 1941 and 1945 primarily in conjunction with forces from the United States.[15] Nearly 400,000 men served overseas, with 40 percent of the total force serving in front line areas.[3]

Organisation[]

Origin of the Second Australian Imperial Force[]

Australia entered World War II on 3 September 1939. On 14 September Prime Minister Robert Menzies announced that 40,000 members of the Militia would be called up for training and a 20,000-strong expeditionary force, designated the Second Australian Imperial Force, would be formed for overseas service. Like its predecessor, the Second AIF was a volunteer force formed by establishing entirely new units. In many cases these units drew their recruits from the same geographical areas as First AIF units, and they were given the same numerical designations albeit with the prefix "2/".[16]

In October 1939, conscription was introduced to keep the Militia at strength as its members volunteered for the AIF. From January 1940, all unmarried men turning 21 were required to report to be examined for potential service. While a substantial proportion of these men were granted exemptions on medical grounds or because they would suffer financial hardship if forced to enter the military, the remainder were liable for three months training followed by ongoing reserve service.[5][17] A side effect of this arrangement was the creation of two different armies with different conditions of service, one the part-volunteer part-conscript Militia and the other the all-volunteer AIF. This situation resulted in administrative and structural problems that existed throughout the war, as well as a sometimes bitter professional rivalry between the men of the two forces.[16] Later, provision was made to allow Militia units to transfer to the AIF if sufficient numbers of personnel volunteered to serve under AIF terms of service. This required 65 percent of a unit's war establishment—or 75 percent of its actual strength—to volunteer and allowed whole battalions to become part of the AIF.[12]

An early problem was whether to adopt the British or Australian organisation. In 1939 the British Army was in the process of re-equipping with new weapons, and a new organisation was required. This new equipment was not available in Australia, so it was decided to organise the first unit to be raised—the 6th Division—with some elements of the old organisation and some of the new.[18] Consequently, the 6th Division was raised as an infantry division of around 18,000 personnel,[19] and initially comprised twelve 900-man infantry battalions each consisting of four rifle companies, a battalion headquarters, regimental aid post and a headquarters company with various support platoons and sections including signals, mortars, carriers, pioneers, anti-aircraft and administration. Artillery support was provided by three field regiments, each attached at brigade-level, as well an anti-tank regiment attached at divisional level and a divisional cavalry regiment which was equipped with armoured vehicles. Corps troops included a machine-gun battalion, and various engineer, logistics and communication units.[20][21][22]

Three further AIF infantry divisions were formed during 1940: the 7th Division in February 1940, the 8th Division in May and the 9th Division in June.[23] However, the establishment of these divisions was reduced to the new nine-battalion organisation as the size of an Australian division was reduced to approximately 17,000 men,[24] and the three surplus battalions of the 6th Division became part of the 7th Division.[25] Further changes included the addition of a light anti-aircraft regiment at divisional level, and a reorganisation of the divisional artillery from three four-battery regiments consisting of 16 guns to three two-battery regiments of 24 guns.[26] An AIF corps headquarters, designated I Corps, was formed in March 1940 along with various support units.[27] The 1st Armoured Division, the final AIF division to be formed, was established in July 1941, built around a core of two armoured brigades each consisting of three tank-equipped armoured regiments, supported by motorised cavalry, armoured cars, engineers and artillery. Several units, such as Z and M Special Units, were also raised for irregular warfare as were 12 commando companies. Many corps, support and service units were also raised during the war to provide combat and logistical support.[28]

Forces in Australia and the Pacific[]

The Army's command and administrative arrangements at the start of the war were based on a system of military districts that had existed since Federation, albeit with a number of modifications.[29] Australia was divided into six military districts each of which largely equated to a State or Territory, and reported to the Department of the Chief of the General Staff. Meanwhile, the Military Board was responsible for the administration of the Army, with regular members consisting of the Deputy Adjutant-General, the Chief of Intelligence, the Chief of the General Staff, the Chief of Ordnance and a civilian Finance Member, in addition to a number of consultative members, under the overall control of the Minister of the Defence.[30] The 1st Military District (1 MD) encompassed Queensland, the 2nd included most of New South Wales, the 3rd was primarily based on Victoria, the 4th included South Australia, the 5th included Western Australia and the 6th encompassed forces in Tasmania. In 1939 the Northern Territory was designated the 7th Military District, while and the 8th Military District was later activated in Port Moresby to command forces in New Guinea.[31]

Following the outbreak of World War II a regional command structure was subsequently adopted, with 2 MD becoming Eastern Command, 5 MD redesignated Western Command, while 1 MD in Queensland became Northern Command and the three southern states of New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania were amalgamated into Southern Command.[31] In the early years of the war this structure proved effective for operations overseas; however, as the threat of war with Japan grew the various commands and military districts came under greater pressure. The activation of the Militia for full-time duty after Japan's entry into the war in late 1941 compounded the situation.[29] In response, the Army command structure was reorganised in early 1942. While Western Australia remained unchanged, Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia were redesignated as Lines of Communications Areas, 7 MD became Northern Territory Force and 8 MD was redesignated as New Guinea Force.[31] In July 1942 the Military Board's functions were assumed by the commander of the military forces, General Sir Thomas Blamey.[30]

The AIF's requirements for manpower and equipment constrained the Militia during the early years of the war.[32] At the outbreak of the Pacific War the main Army units in Australia were five Militia infantry divisions—the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th Divisions—two Militia cavalry divisions—the 1st and 2nd Cavalry Divisions—and the AIF 1st Armoured Division.[33] The Volunteer Defence Corps (VDC), which was a part-time volunteer force of 100,000 men based on the British Home Guard, was also available for local defence.[34] In addition, by early 1942 there were 12,000 garrison force personnel—mostly reservist veterans of World War I—organised into 13 garrison battalions for coastal defence and five battalions and two companies for internal security tasks, including guarding prisoner of war camps.[33] Yet at this time only 30 percent of Militia units were on full-time duty, with the remainder periodically undertaking three month-long mobilisations.[35] The Militia was also poorly armed, and there was insufficient equipment to be issued to all units if they were mobilised.[36] In response to the Japanese threat following the outbreak of the Pacific War and the capture of the 8th Division in Malaya, the condition of the Militia became a pressing concern, after largely having been ignored since 1940. Several middle-ranking and senior officers of the AIF were subsequently posted to Militia units and formations to give them experience.[37] Meanwhile, the Army was forced to move units between Militia divisions so that the most combat-ready could be sent to areas believed to be under the greatest threat of attack.[38] Some battalions were amalgamated, and although some were later separated and reformed, others were disbanded altogether.[37] After the Defence (Citizen Military Forces) Act 1943 was passed Militia units were able to serve outside Australian territory in the South West Pacific Area from January 1943, though the 11th Brigade was the only major formation to do so.[39]

The Army was considerably expanded in early 1942 in response to the Japanese threat to Australia. During this year the Army's strength peaked at eleven infantry divisions—the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, 9th, 10th, 11th and 12th Divisions—and three armoured divisions—the 1st, 2nd and 3rd—organised into the First and Second Armies, and I, II and III Corps, as well as many support and service units.[14] In August 1942, the Army had a strength of 476,000 men.[40] This force proved larger than what Australia's population and industry could sustain; by late 1942 the number of personnel who needed to be inducted each month to make good losses caused by sickness and combat was much larger than the numbers who were becoming eligible for service, and the allocation of a high proportion of Australia's limited supply of manpower to the military was inhibiting the expansion of the munitions industry and other key sectors of the economy.[41][42] The Army was also unbalanced as a large majority its personnel were employed in arms corps undertaking combat and combat support roles. Heavily reliant upon its allies for logistical support, it required more personnel in support arms such as ordnance and transport to be functional as a self-sufficient organisation. This situation was most acute in 1942; at that time there were 137,236 men serving arms corps such as infantry, cavalry and armour, while there were just 29,079 in ordnance.[40]

This imbalance was slowly addressed after 1942 as the Army's size was reduced. Most of the units that were disbanded were Militia arms corps units, and by September 1943 the AIF outnumbered the Militia, having 265,000 members compared to just over 117,000.[43] Further reductions came in October 1943 when the Army's strength was further reduced by 100,000 men to free up manpower to work in industry.[44] At the end of 1943 the Army's strength was set at six infantry divisions and two armoured brigades, although further reductions were ordered in August 1944 and June 1945.[45] By 1945 the support arms had grown considerably as a proportion of the total force and by August 1945 ordnance and the electrical and mechanical engineers totalled 42,835 men, while the artillery had been reduced to half its previous strength. Infantry, cavalry and armoured corps personnel numbered just 62,097 men, while engineers, signals and the medical services remained the same, albeit as part of a much smaller Army.[40] Regardless, at the end of the war it remained one of the largest Allied armies as a proportion of population, being second only to the Soviet Union.[14][46] The VDC was also reduced in size in May 1944, and was finally disbanded on 24 August 1945.[47] If the conflict had continued past August 1945, the size of the Army would have been further reduced to three divisions once Bougainville, New Guinea and New Britain had been secured. Two of these divisions would have been used on garrison duties, while a brigade group may have been made available for British-led operations in South East Asia and the remaining division was to take part in the invasion of Japan.[48]

The demands of combat during World War II led to changes in the composition of Army units. The success of German mechanised units during the invasions of Poland and France convinced Australian defence planners that the Army required armoured units, and these began to be raised in 1941 when the 1st Armoured Division was formed. The two Militia cavalry divisions were first motorised and then converted into armoured divisions in 1942 and the 3rd Army Tank Brigade was formed to provide support to the infantry. These large armoured units were not suitable for jungle warfare, however, and most were disbanded during 1943 and 1944.[49] Conditions in the South West Pacific also led the Army to convert its six combat divisions to jungle divisions in early 1943 and 1944, reducing the authorised strength of the division by about 4,000 men. Each infantry battalion shed around 100 personnel as various support elements such as the anti-aircraft and carrier platoons were removed and consolidated at divisional level.[50] The amount of heavy weapons and vehicles was also reduced, but the conditions that the organisation was designed for did not recur and it proved only moderately successful.[51] As a result, the divisions were strengthened for their 1944–45 campaigns by returning the artillery and anti-tank units that had been removed.[52] The creation of the jungle divisions represented the first time in the Australian Army's history that it had adopted an organisation specifically for the conditions in which its forces would fight. Previously force structure had been heavily influenced by the British Army, and the decision to adopt an organisation to suit local conditions reflected a growing maturity and independence.[53] Yet it also resulted in the adoption of a two-tier force structure, as formations that were not designated for jungle warfare remained on the previous scales of equipment and manning. Ultimately, while their structure was better suited to operations in Australia, they were no longer able to be used against the Japanese. As a result, the burden of the fighting increasingly fell on those formations that had been re-organised, while the remainder of the Army was relegated to garrison duties.[54]

The Army also raised many anti-aircraft and coastal defence units during the war. The pre-war coastal defences were greatly expanded from 1939, and many new batteries were built near major ports in Australia and New Guinea in response to the threat of Japanese attack. Australia had a limited capacity to produce anti-aircraft guns, and the bulk of equipment had to come from Britain. As such the development of such defences was initially hampered by a lack of available equipment. The coastal defence system reached its peak size during 1944.[55] The Army had few anti-aircraft guns at the outbreak of war, and a high priority was given to expanding the air defences around major cities and important industrial and military facilities. By 1942 anti-aircraft batteries were in place around all the major cities as well as the key towns in northern Australia.[56] The expansion of the artillery in general, and coastal defence and anti-aircraft units in particular, meant that by June 1942 some 80,000 of the 406,000 members of the Army were artillerymen.[57] VDC units gradually took over responsibility for manning the fixed coastal and anti-aircraft defences as the threat of attack against the Australian mainland receded.[47]

Traditionally the Australian Army had relied on its major allies to provide logistic support, primarily raising combat units rather than support arms during times of conflict. Consequently, these services were relatively underdeveloped, and they remained so during the first years of the war. While British units provided many logistic and line of communication services for the AIF in North Africa during the early campaigns in 1940 and 1941, the Army needed to raise extensive support units to support its combat formations in the Pacific following the Japanese entry into the war.[58] As a result, the growth of the support arms and ancillary services proved dramatic, including many capabilities which the Australian Army had only minimal or no previous experience in maintaining. These units included terminal formations and beach groups responsible for loading and unloading ships, food and petroleum storage and distribution units and several farm units which grew food for troops in remote areas. In addition, with Australia's national support base located well to the rear, in the major cities in the south-east of the country, significant expansion of the Army's transport capabilities was required to move supplies and men to the field force based in northern Australia and New Guinea. Many road transport units were raised to move supplies around Australia, while the Royal Australian Engineers eventually operated a fleet of 1,900 watercraft and three air maintenance companies were formed to load supply aircraft.[59]

Women's services[]

Prior to World War II the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS) was the only female branch of the Army. A reserve formation that had served overseas during World War I, the AANS was mobilised following the outbreak of war in 1939 and its Matron in Chief, Grace Wilson, served on the staff of the Director-General of Medical Services, Major General Rupert Downes.[60][61] For most of the war, AANS nurses were the only Australian servicewomen permitted to serve overseas, and many volunteered for the AIF. These women served in all the major theatres in which the Army fought and a total of 71 were killed on active service. The majority of these died in early 1942 during the fighting in Malaya and Singapore where 41 nurses were killed.[62] In March 1942, the Volunteer Aid Detachments (VADs) also became a branch of the Army Medical Service. Consisting of volunteers originally coordinated by the Australian Red Cross and Order of Saint John, the VADs were redesignated the Australian Army Medical Women's Service (AAMWS) in December 1942, and were employed in military hospitals in Australia and overseas until after the end of the war, before returning to civilian control in 1948.[63]

Shortages of manpower also led to the establishment of the Australian Women's Army Service (AWAS) in August 1941. AWAS members filled a wide range of roles to allow the Army to redeploy male soldiers to fighting units. While they mainly worked in clerical and administrative positions, and auxiliary roles such as drivers and signallers, many served in anti-aircraft batteries, operating radars and searchlights but not the guns themselves.[64] While Blamey sought to have members of the AWAS posted overseas from early 1941 onwards, the Australian Government did not agree to this until 1945.[65] As a result, only about 400 of the 24,000 women who joined the AWAS served outside Australia.[66] The AWAS was reduced in size following the war, and was finally disbanded on 30 June 1947.[65] Colonel Sybil Irving commanded the AWAS from September 1941 until 1947.[67] In total some 35,000 women served in the Army, making up about 5 percent of the force.[68]

Campaigns[]

North Africa[]

During the first years of World War II, Australia's military strategy was closely aligned with that of the United Kingdom's imperial defence policy. The Singapore strategy, which seemingly negated the need for large-scale land forces in the Pacific, was a key component of this policy and consequently most Australian military units that were deployed overseas in 1940 and 1941 were sent to the Mediterranean and Middle East where they formed an integral part of the Commonwealth forces in the area. The three AIF infantry divisions dispatched to the Middle East were subsequently heavily involved in the fighting that followed.[69] In addition to the force which was sent to North Africa, two AIF brigades (the 18th and 25th) were stationed in Britain from June 1940 to January 1941 and formed part of the British mobile reserve which would have responded to any German landings. The Australian Forestry Group UK also served in Britain between 1940 and 1943.[70]

The Australian Army first saw action in Operation Compass, the successful Commonwealth offensive in North Africa which was conducted between December 1940 and February 1941. Although the 6th Division was not fully equipped, it had completed its training and on 14 December, it relieved the 4th Indian Division. Given the task of capturing Italian fortresses bypassed by the British 7th Armoured Division during its advance,[71] on 3 January, the division went into action at Bardia. Although the fortress was manned by a larger force, the Australian infantry quickly penetrated the Italian defensive lines with the support of British tanks and artillery. The majority of the defenders surrendered on 5 January and the Australians took 40,000 prisoners.[72] The 6th Division followed up this success by assaulting the fortress of Tobruk on 21 January, securing it the next day and taking 25,000 Italians prisoner.[73] After this, the Australians pushed west along the coast road to Cyrenaica and captured Benghazi on 4 February.[74] Later that month, the 6th Division was withdrawn for deployment to Greece and was replaced by the untested 9th Division, which took up garrison duties in Cyrenaica.[75]

In the last week of March 1941, a German-led force launched an offensive in Cyrenaica. The Allied forces in the area were rapidly forced to withdraw towards Egypt. The 9th Division formed the rear guard of this withdrawal, and on 6 April was ordered to defend the important port town of Tobruk for at least two months. Sustained by the Australian destroyers of the Mediterranean Fleet, during the ensuing siege the 9th Division, reinforced by the 7th Division's 18th Brigade as well as British artillery and armoured regiments, used fortifications, aggressive patrolling and artillery to contain and defeat repeated German armoured and infantry attacks. In September and October 1941, upon the request of the Australian Government, the 9th Division was relieved and the bulk withdrawn from Tobruk. The 2/13th Battalion, however, was forced to remain until the siege was lifted in December as the convoy evacuating it was attacked. The defence of Tobruk cost the Australian units involved 3,009 casualties, including 832 killed and 941 taken prisoner.[76]

Greece, Crete, Syria and Lebanon[]

In early 1941 the 6th Division and I Corps headquarters took part in the ill-fated Allied expedition to defend Greece from a German invasion. The corps' commander, Lieutenant General Thomas Blamey, and Prime Minister Menzies both regarded the operation as risky, but agreed to Australian involvement after the British Government provided them with briefings which deliberately understated the chance of defeat. The Allied force deployed to Greece was much smaller than the German force in the region and the defence of the country was compromised by inconsistencies between Greek and Allied plans.[77]

Australian troops arrived in Greece during March and manned defensive positions in the north of the country alongside British, New Zealand and Greek units. The outnumbered Allied force was not able to halt the Germans when they invaded on 6 April and was forced to retreat. The Australians and other Allied units conducted a fighting withdrawal from their initial positions and were evacuated from southern Greece between 24 April and 1 May. Australian warships also formed part of the force which protected the evacuation and embarked hundreds of soldiers from Greek ports. The 6th Division suffered heavy casualties in this campaign, with 320 men killed and 2,030 captured.[78]

While most of the 6th Division returned to Egypt, the 19th Brigade Group and two provisional infantry battalions landed at Crete where they formed a key part of the island's defences. The 19th Brigade was initially successful in holding its positions when German paratroopers landed on 20 May, but was gradually forced to retreat. After several key airfields were lost the Allies evacuated the island's garrison. Approximately 3,000 Australians, including the entire 2/7th Battalion, could not be evacuated, and were taken prisoner.[79] As a result of its heavy casualties the 6th Division required substantial reinforcements and equipment before it was again ready for combat.[80]

The 7th Division, reinforced by the 6th Division's 17th Brigade, formed a key part of the Allied ground forces during the Syria–Lebanon campaign which was fought against Vichy French forces in June and July 1941.[81] With close air support from the RAAF and the Royal Air Force, the Australian force entered Lebanon on 8 June and advanced along the coast road and Litani River valley. Although little resistance had been expected, the Vichy forces mounted a strong defence which made good use of the mountainous terrain.[82] After the Allied attack became bogged down reinforcements were brought in and the Australian I Corps headquarters took command of the operation on 18 June. These changes enabled the Allies to overwhelm the French forces and the 7th Division entered Beirut on 12 July. The loss of Beirut and a British breakthrough in Syria led the Vichy commander to seek an armistice and the campaign ended on 13 July.[83]

El Alamein[]

In the second half of 1941 the Australian I Corps was concentrated in Syria and Lebanon where it undertook garrison duties while its strength was rebuilt ahead of further operations in the Middle East. Following the outbreak of war in the Pacific most elements of the corps, including the 6th and 7th Divisions, returned to Australia in early 1942 to counter the perceived Japanese threat to Australia. The Australian Government agreed to requests from Britain and the United States to temporarily retain the 9th Division in the Middle East in exchange for the deployment of additional US troops to Australia and Britain's support for a proposal to expand the RAAF to 73 squadrons.[84] The Government did not intend that the 9th Division would play a major role in active fighting, and it was not sent any further reinforcements.[85]

In mid-1942, the Axis forces defeated the Commonwealth force in Libya and advanced into north-west Egypt. In June the British Eighth Army made a stand just over 100 kilometres (62 mi) west of Alexandria, at the railway siding of El Alamein and the 9th Division was brought forward to reinforce this position. The lead elements of the division arrived at El Alamein on 6 July and it was assigned the most northerly section of the Commonwealth defensive line. From that position, the 9th Division subsequently played a significant role in the First Battle of El Alamein, helping to halt the Axis advance. Casualties were heavy, and the 2/28th Battalion was forced to surrender on 27 July when it was surrounded by German armour after capturing Ruin Ridge.[86] Following this battle the division remained at the northern end of the El Alamein line and launched diversionary attacks during the Battle of Alam el Halfa in early September.[87]

In October 1942, the 9th Division and the RAAF squadrons in the area took part in the Second Battle of El Alamein. After a lengthy period of preparation, the Eighth Army launched its major offensive on 23 October. The 9th Division was involved in some of the heaviest fighting of the battle, and its advance in the coast area succeeded in drawing away enough German forces for the heavily reinforced 2nd New Zealand Division to decisively break through the Axis lines on the night of 1/2 November. The 9th Division suffered a high number of casualties during this battle and did not take part in the pursuit of the retreating Axis forces.[88] During the battle the Australian Government requested that the division be returned to Australia as it was not possible to provide enough reinforcements to sustain it, and this was agreed to by the British and US governments in late November. The 9th Division left Egypt for Australia in January 1943, ending the AIF's involvement in the war in North Africa.[89]

Malaya and Singapore[]

Due to the emphasis placed on cooperation with Britain, relatively few Australian military units were stationed in Australia and the Asia-Pacific region after 1940. Measures were taken to improve Australia's defences as war with Japan loomed in 1941, but these proved inadequate. The 8th Division was subsequently dispatched to Singapore in February 1941, while plans were made for a Militia battalion to be stationed between Port Moresby and Thursday Island. An AIF battalion was also allocated to garrison Rabaul, and another brigade would be dispersed piecemeal to Timor and Ambon.[90] Meanwhile, in July 1941 the 1st Independent Company was deployed to Kavieng on New Britain in order to protect the airfield, while sections were sent to Namatanai in central New Ireland, Vila in the New Hebrides, Tulagi on Guadalcanal, Buka Passage in Bougainville, and Lorengau on Manus Island to act as observers.[90]

In December 1941 the Australian Army in the Pacific consisted of the 8th Division, most of which was stationed in Malaya, and eight partially trained and equipped divisions in Australia, including the 1st Armoured Division.[91] In keeping with the Singapore strategy, a high proportion of Australian forces in Asia were concentrated in Malaya during 1940 and 1941 as the threat from Japan increased.[6] At the outbreak of war the Australian forces in Malaya consisted of two brigade groups from the 8th Division—the 22nd and 27th Brigades—under the command of Major General Gordon Bennett, along with four RAAF squadrons and eight warships.[92]

Following the Japanese invasion on 8 December 1941, the 8th Division and its attached Indian Army units was assigned responsibility for the defence of Johore in the south of Malaya.[93] As a result, it did not see action until mid-January 1942 when Japanese spearheads first reached the state, having pushed back the British and Indian units defending the northern parts of the peninsula. By this time, the division's two brigades had been split up, with the 22nd having been deployed around Mersing and Endau on the east coast and the 27th in the west.[94] The division's first engagement came on the west coast around Muar on 14 January, where the Japanese Twenty-Fifth Army was able to outflank the Commonwealth positions due to Bennett misdeploying the forces under his command so that the weak Indian 45th Brigade was assigned the crucial coastal sector and the stronger Australian brigades were deployed in less threatened areas. While the Commonwealth forces in Johore achieved a number of local tactical victories, most notably around Gemas, Bakri, and Jemaluang,[95] they were unable to do more than slow the Japanese advance and suffered heavy casualties in doing so. After being outmanoeuvred by the Japanese, the remaining Commonwealth units withdrew to Singapore on the night of 30–31 January.[96]

Following this the 8th Division was deployed to defend Singapore's north-west coast. Due to the casualties suffered in Johore most of the division's units were at half-strength, and the replacements that had been received—a draft of about 1,900 replacements was sent in late January—were barely trained, some having as little as two weeks' training in Australia before being dispatched.[97] Assigned larger-than-normal frontages to defend along beaches that were ill-suited for defence, the 22nd and 27th Brigades were spread thin on the ground with large gaps in their lines.[98] The commander of the Singapore fortress, Lieutenant General Arthur Ernest Percival, believed that the Japanese would land on the north-east coast of the island and deployed the near full-strength British 18th Division to defend this sector. Nevertheless, on 8 February the Japanese landed in the Australian sector, and the 8th Division was forced from its positions after just two days of heavy fighting. A subsequent landing took place at Kranji, but the division was unable to turn this back and subsequently withdrew to the centre of the island.[99]

After further fighting in which the Commonwealth forces were pushed into a narrow perimeter around the urban area of Singapore, Percival surrendered his forces on 15 February. Although some Australians were able to escape, following the capitulation 14,972 Australians were taken prisoner.[100] Bennett was among those that managed to get out, having left the island the night before the surrender via sampan after handing over command of his division to Brigadier Cecil Callaghan. He later justified his actions saying that he had gained an understanding of how to defeat the Japanese and needed to return to Australia to pass his knowledge on, but two post-war inquiries found that he was unjustified in leaving his command.[101] The loss of almost a quarter of Australia's overseas soldiers and the failure of the Singapore strategy that had permitted it to accept the sending of the AIF to aid Britain, stunned the country.[102]

The fall of Singapore raised fears of a Japanese invasion of the Australian mainland and the Government became concerned about the Army's ability to respond. Although large, the forces in Australia contained many inexperienced units and lacked mobility.[103] In response, most of the AIF was brought back from the Middle East and the Australian Prime Minister, John Curtin, appealed to the United States for assistance. As Japanese forces advanced through Burma towards India in early 1942, the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, attempted to divert the 6th and 7th Divisions while they were en route to Australia, but Curtin refused to authorise this movement. As a compromise the 16th and 17th Brigades of the 6th Division disembarked at Ceylon and formed part of the island's garrison until they returned to Australia in August 1942.[104]

Netherlands East Indies and Rabaul[]

While Australia's contribution to the pre-war plans to defend South East Asia from Japanese aggression was focused on the defence of Malaya and Singapore, small Australian forces were also deployed to defend several islands to the north of Australia. The role of these forces was to defend strategic airfields which could be used to launch attacks on the Australian mainland.[105] Detachments of coastwatchers were also stationed in the Bismarck Archipelago and Solomon Islands to report on any Japanese operations there.[106]

At the start of the Pacific War the strategic port town of Rabaul in New Britain was defended by "Lark Force", which comprised the 2/22nd Battalion reinforced with coastal artillery and a poorly equipped RAAF bomber squadron. While Lark Force was regarded as inadequate by the Australian military,[107] it was not possible to reinforce it before the Japanese South Seas Force landed at Rabaul on 23 January 1942. The outnumbered Australian force was swiftly defeated and most of the survivors surrendered in the weeks after the battle. Few members of Lark Force survived the war, as at least 130 were murdered by the Japanese on 4 February and 1,057 Australian soldiers and civilian prisoners from Rabaul were killed when the ship carrying them to Japan, the transport Montevideo Maru, was sunk by a US submarine on 1 July 1942.[108]

AIF troops were also dispatched from Darwin to the Netherlands East Indies (NEI) in the first weeks of the Pacific War. Reinforced battalions from the 8th Division's third brigade, the 23rd, were sent to Koepang in West Timor as part of "Sparrow Force" and to the island of Ambon as "Gull Force" to defend these strategic locations from Japanese attack. The 2/2nd Independent Company was also sent to Dili in Portuguese Timor in violation of Portugal's neutrality.[107] The force at Ambon was defeated by the Japanese landing on 30 January and surrendered on 3 February 1942. Over 300 Australian prisoners were subsequently killed by Japanese troops in a series of mass executions during February.[109] While the force at Koepang was defeated after the Japanese landed there on 20 February and also surrendered, Australian commandos waged a guerrilla campaign against the Japanese in Portuguese Timor until February 1943.[110]

In the lead-up to the Japanese invasion of Java a force of 242 carrier- and land-based aircraft attacked Darwin on 19 February 1942. At the time Darwin was an important base for Allied warships and a staging point for shipping supplies and reinforcements into the NEI. The Japanese attack was successful, and resulted in the deaths of 251 civilians and military personnel, most of whom were non-Australian Allied seamen, and heavy damage to RAAF Base Darwin and the town's port facilities.[111]

A 3,000-strong Army unit, as well as several Australian warships and aircraft from a number of RAAF squadrons participated in the unsuccessful defence of Java when the Japanese invaded the island in March 1942. An Army force made up of elements from the 7th Division also formed part of the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDACOM) land forces on Java but saw little action before it surrendered at Bandung on 12 March after the Dutch forces on the island began to capitulate.[112] Following the conquest of the NEI, the Japanese Navy's main aircraft carrier force raided the Indian Ocean, attacking Ceylon in early April. The two Australian Army brigades stationed at Ceylon at the time of the raid were placed on alert to repel a potential invasion but did not see action as this did not eventuate.[113]

Defence of Australia[]

Japan's rapid advance south had been unexpected,[114] and the perceived threat of invasion led to a major expansion of the Australian military. By mid-1942 the Army had a strength of ten infantry divisions, three armoured divisions and hundreds of other units.[115] Thousands of Australians who were ineligible for service in the military responded to the threat of attack by joining auxiliary organisations such as the Volunteer Defence Corps and Volunteer Air Observers Corps, which were modelled on the British Home Guard and Royal Observer Corps respectively.[116] However, Australia's population and industrial base were not sufficient to maintain these forces once the threat of invasion had passed, and the Army was progressively reduced in size from 1943.[41]

Despite Australian fears, the Japanese never intended to invade the Australian mainland. While an invasion was considered by the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters in February 1942, it was judged to be beyond the Japanese military's capabilities and no planning or other preparations were undertaken.[117] Instead, in March 1942 the Japanese military adopted a strategy of isolating Australia from the United States by capturing Port Moresby in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, Fiji, Samoa and New Caledonia.[118] Yet this plan was frustrated by the Japanese defeat in the Battle of the Coral Sea and was postponed indefinitely after the Battle of Midway.[119] While these battles ended the threat to Australia, the Australian government continued to warn that an invasion was possible until mid-1943.[117] A series of Japanese air raids against northern Australia occurred during 1942 and 1943, and while the main defence was provided by RAAF and Allied fighters, a number of Australian Army anti-aircraft batteries were also involved in dealing with this threat.[120]

Meanwhile, in 1942 the Australian military was reinforced by units recalled from the Middle East and an expansion of the Militia and RAAF. United States military units also arrived in Australia in great numbers before being deployed to New Guinea, and in April 1942 command of Australian and US forces in the South West Pacific was consolidated under an American commander, General Douglas MacArthur.[121] After halting the Japanese the Allies moved onto the offensive in late 1942, with the pace of advance accelerating in 1943. From 1944 the Australian military was mainly relegated to subsidiary roles in holding or mopping-up operations, but continued to conduct large-scale operations until the end of the war with a larger proportion of its forces deployed in the final months of the conflict than at any other time.[122]

Papuan campaign[]

Japanese forces first landed on the mainland of New Guinea on 8 March 1942 when they invaded Lae and Salamaua to secure bases for the defence of the important base they were developing at Rabaul. In response, Australian guerrillas from the New Guinea Volunteer Rifles established observation posts around the Japanese beachheads and the 2/5th Independent Company successfully raided Salamaua on 29 June.[123] After the Battle of the Coral Sea frustrated the Japanese plan to capture Port Moresby via an amphibious landing, they attempted to capture the town by landing Major General Tomitarō Horii's South Seas Force at Buna on the north coast of Papua and advancing overland using the Kokoda Track to cross the rugged Owen Stanley Range.[124] The Kokoda Track campaign began on 22 July when the Japanese began their advance, opposed by an ill-prepared Militia brigade designated "Maroubra Force". This force was successful in delaying the South Seas Force but was unable to halt it.[125]

In late August and early September 1942 Australian forces at Milne Bay inflicted the first notable land defeat of the war upon the Japanese.[126] After the Japanese landed a unit of Special Naval Landing Forces to capture the airbases that the Allies had established in the area, two brigades of Australian troops—the Militia 7th and AIF 18th—designated "Milne Force", supported by two RAAF fighter squadrons and US Army engineers, launched a counter-attack. Outnumbered, lacking supplies and suffering heavy casualties, the Japanese were forced to withdraw. The victory helped raise Allied morale across the Pacific Theatre, especially on the Kokoda Track where the Japanese had continued to make progress throughout August.[127][128]

On 26 August two AIF battalions from the 7th Division reinforced the remnants of Maroubra Force but the Japanese continued to advance along the Kokoda Track and by 16 September they reached the village of Ioribaiwa near Port Moresby.[125] After several weeks of exhausting fighting and heavy losses, the Japanese troops were within 32 kilometres (20 mi) of Port Moresby. Yet supply problems made any further advance impossible, and the Japanese began to fear an Allied counter-landing at Buna.[129] Following reverses at the hands of US forces on Guadalcanal the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters decided they could not support fronts on both New Guinea and Guadalcanal. Horii was subsequently ordered to withdraw his troops on the Kokoda Track until the issue at Guadalcanal was decided.[130]

After this, the Australian forces were heavily reinforced by the 7th Division's 21st and 25th Brigades. Supported logistically by native Papuans who were recruited by the Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit, often forcibly, to carry supplies and evacuate wounded personnel,[131] the Australians pursued the Japanese back along the Kokoda Track. In early November, they had been forced into a small bridgehead on the north coast of Papua.[132] Australian and US forces attacked the Japanese bridgehead in Papua in late November 1942. The Allied force consisted of the exhausted 7th Division and the inexperienced and ill-trained US 32nd Infantry Division, and was short of artillery and supplies. Due to a lack of supporting weapons and MacArthur and Blamey's insistence on a rapid advance the Allied tactics during the battle were centred on infantry assaults on the Japanese fortifications. These resulted in heavy casualties and the area was not secured until 22 January 1943.[133]

Throughout the fighting in Papua, most of the Australian personnel captured by Japanese troops were murdered. In response, for the remainder of the war Australian soldiers generally did not attempt to capture Japanese personnel and aggressively sought to kill their Japanese opponents including some that had surrendered.[134] Following the defeats in Papua and Guadalcanal the Japanese withdrew to a defensive perimeter in the Territory of New Guinea.[135] Meanwhile, during the fighting in 1942–43 the Australian Army increasingly developed a tactical superiority over the Japanese in jungle warfare.[136][137]

The Papuan campaign led to a significant reform in the composition of the Australian Army. During the campaign, the restriction banning Militia personnel from serving outside of Australian territory hampered military planning and caused tensions between the AIF and Militia. In late 1942 and early 1943 Curtin overcame opposition within the Labor Party to extending the geographic boundaries in which conscripts could serve to include most of the South West Pacific and the necessary legislation was passed in January 1943.[138] This made deploying the Militia easier, but ultimately only one brigade, the 11th, was dispatched outside of Australian territory, being deployed to Merauke on the south coast of Dutch West Papua in the NEI during 1943 and 1944 as part of "Merauke Force".[37]

New Guinea offensives[]

After halting the Japanese advance, Allied forces went on the offensive across the SWPA from mid-1943. Australian forces played a key role throughout this offensive, which was designated Operation Cartwheel. In particular, Blamey oversaw a series of highly successful operations around the north-east tip of New Guinea which "was the high point of Australia's experience of operational level command" during the war.[139] After the successful defence of Wau the 3rd Division began advancing towards Salamaua in April 1943. This advance was mounted to divert attention from Lae, which was one of the main objectives of Operation Cartwheel, and proceeded slowly. In late June the 3rd Division was reinforced by the US 162nd Regimental Combat Team, which staged an amphibious landing to the south of Salamaua. The town was eventually captured on 11 September 1943.[140]

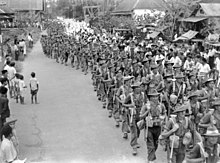

In early September 1943 Australian-led forces mounted a pincer movement to capture Lae. On 4 September the 9th Division made an amphibious landing to the east of the town and began advancing to the west. The following day, the US 503rd Parachute Regiment made an unopposed parachute drop at Nadzab, just west of Lae. Once the airborne forces secured Nadzab Airfield, the 7th Division was flown in and began advancing to the east in a race with the 9th Division to capture Lae. This race was won by the 7th Division, which captured the town on 15 September. The Japanese forces at Salamaua and Lae suffered heavy losses during this campaign, but were able to escape to the north.[141]

After the fall of Lae the 9th Division was given the task of capturing the Huon Peninsula. The 20th Brigade landed near the strategic harbour of Finschhafen on 22 September 1943 and secured the area. The Japanese responded by dispatching the 20th Division overland to the area and the remainder of the 9th Division was gradually brought in to reinforce the 20th Brigade against the expected counter-attack. The Japanese mounted a strong attack in mid-October which was defeated by the 9th Division after heavy fighting. During the second half of November the 9th Division captured the hills inland of Finschhafen from well dug in Japanese forces. Following its defeat, the 20th Division retreated along the coast with the 9th Division and 4th Brigade in pursuit.[142]

While the 9th Division secured the coastal region of the Huon Peninsula the 7th Division drove the Japanese from the inland Finisterre Range. The Finisterre Range campaign began on 17 September when the 2/6th Independent Company was air-landed in the Markham Valley. The company defeated a larger Japanese force at Kaiapit and secured an airstrip which was used to fly in the division's 21st and 25th Brigades. Through aggressive patrolling the Australians forced the Japanese out of positions in extremely rugged terrain and in January 1944 the division began its attack on the key Shaggy Ridge position. The ridge was taken by the end of the month, with the RAAF playing a key supporting role. Following this success the Japanese withdrew from the Finisterre Range and Australian troops linked up with American patrols from Saidor on 21 April and secured Madang on 24 April.[143]

Advance to the Philippines[]

The Australian military's role in the South-West Pacific decreased during 1944 as US forces took over responsibility for the main Allied effort in the region.[144] In the latter half of 1943 the Australian Government decided, with MacArthur's agreement, that the size of the military would be decreased to release manpower for war-related industries which were important to supplying Britain and US forces in the Pacific. Australia's main role in the Allied war effort from this point forward was supplying the other Allied countries with food, materials and manufactured goods needed for the defeat of Japan.[145] As a result of this policy, the size of the Army was reduced from late 1943 onwards, though an offensive force of six infantry divisions (three AIF and three Militia divisions) was maintained until the end of the war.[146] In early 1944 all but two of the Army's divisions were withdrawn to the Atherton Tableland for training and rehabilitation.[147] However, several new battalions of Australian-led Papuan and New Guinea troops were formed during 1944 and organised into the Pacific Islands Regiment. These troops had earlier seen action alongside Australian units throughout the New Guinea campaign, and they largely replaced the Australian Army battalions disbanded during the year.[148]

While the Australian Government offered I Corps for use in Leyte and Luzon, nothing came of several proposals to utilise it in the liberation of these islands.[149] The Army's prolonged period of relative inactivity during 1944 led to public concern, and many Australians believed that the AIF should be demobilised if it could not be used for offensive operations.[150] This was politically embarrassing for the government, and helped motivate it to look for new areas where the military could be used.[151] It also impacted upon the Army's morale; as the Allies advanced further towards Japan, the Army was increasingly relegated to "second string" roles, despite having fought "above its weight" for most of the war.[152]

Mopping up in New Guinea and the Solomons[]

In late 1944, the Australian Government committed twelve Australian Army brigades to replace six US Army divisions which were conducting defensive roles in Bougainville, New Britain and the Aitape–Wewak area in New Guinea in order to free up the American units for operations in the Philippines.[153] While the US units had largely conducted a static defence of their positions, their Australian replacements mounted offensive operations designed to destroy the remaining Japanese forces in these areas.[154] The value of these campaigns was controversial at the time and remains so to this day as the Australian Government authorised these operations for primarily political, rather than military, reasons. It was believed that keeping the Army involved in the war would give Australia greater influence in any post-war peace conferences and that liberating Australian territories would enhance Australia's influence in its region.[155] Critics of these campaigns, such as author Peter Charlton, argue that they were unnecessary and wasteful of the lives of the Australian soldiers involved as the Japanese forces were already isolated and ineffective.[156][154]

The 5th Division replaced the US 40th Infantry Division on New Britain during October and November 1944 and continued the New Britain campaign with the goals of protecting Allied bases and confining the large Japanese force on the island to the area around Rabaul. In late November the 5th Division established bases closer to the Japanese perimeter and began aggressive patrols supported by the Allied Intelligence Bureau.[157] The division conducted amphibious landings at Open Bay and Wide Bay at the base of the Gazelle Peninsula in early 1945 and defeated the small Japanese garrisons in these areas. By April the Japanese had been confined to their fortified positions in the Gazelle Peninsula by the Australian force's aggressive patrolling. The 5th Division suffered 53 fatalities and 140 wounded during this campaign. After the war it was found that the Japanese force was 93,000 strong, which was much higher than the 38,000 which Allied intelligence had estimated remained on New Britain.[157]

The II Corps continued the Bougainville campaign after it replaced the US Army's XIV Corps between October and December 1944. The corps consisted of the 3rd Division, 11th Brigade and Fiji Infantry Regiment on Bougainville and the 23rd Brigade which garrisoned neighbouring islands and was supported by RAAF, Royal New Zealand Air Force and United States Marine Corps air units.[158] While the XIV Corps had maintained a defensive posture, the Australians conducted offensive operations aimed at destroying the Japanese force on Bougainville. As the Japanese were split into several enclaves the II Corps fought separate offensives in the northern, central and southern portions of the island. The main focus was against the Japanese base at Buin in the south, and the offensives in the north and centre of the island were largely suspended from May 1945. While Australian operations on Bougainville continued until the end of the war, large Japanese forces remained at Buin and in the north of the island.[159]

The 6th Division was assigned responsibility for completing the destruction of the Japanese Eighteenth Army, which was the last large Japanese force remaining in the Australian portion of New Guinea. Supported by several RAAF squadrons and RAN warships, the division was reinforced by Militia and armoured units and began arriving at Aitape in October 1944.[160] In late 1944 the Australians launched a two-pronged offensive to the east towards Wewak. The 17th Brigade advanced inland through the Torricelli Mountains while the remainder of the division moved along the coast. Although the Eighteenth Army had suffered heavy casualties from previous fighting and disease, it mounted a strong resistance and inflicted significant casualties. The 6th Division's advance was also hampered by supply difficulties and bad weather. The Australians secured the coastal area by early May, and Wewak was captured on 10 May after a small force was landed east of the town. By the end of the war the Eighteenth Army had been forced into what it had designated its "last stand" area. The Aitape–Wewak campaign cost 442 Australian lives while about 9,000 Japanese died and another 269 were taken prisoner.[161]

Borneo campaign[]

The Borneo campaign of 1945 was the last major Allied campaign in the South West Pacific. In a series of amphibious assaults between 1 May and 21 July, the Australian I Corps, under Lieutenant General Leslie Morshead, attacked Japanese forces occupying the island. Allied naval and air forces, centred on the US 7th Fleet under Admiral Thomas Kinkaid, the Australian First Tactical Air Force and the US Thirteenth Air Force, also played important roles in the campaign. The goals of this campaign were to capture Borneo's oilfields and Brunei Bay to support the US-led invasion of Japan and British-led liberation of Malaya which were planned to take place later in 1945.[162] The Australian Government did not agree to MacArthur's proposal to extend the offensive to include the liberation of Java in July 1945, however, and its decision not to release the 6th Division for this operation contributed to it not going ahead.[163]

The campaign opened on 1 May 1945 when the 26th Brigade Group landed on the small island of Tarakan off the east coast of Borneo to secure the island's airstrip as a base to support the planned landings at Brunei and Balikpapan. While it had been expected that it would take only a few weeks to secure Tarakan and re-open the airstrip, intensive fighting on the island lasted until 19 June and the airstrip was not opened until 28 June. As a result, the operation is generally considered to have not been worthwhile.[164]

The next phase began on 10 June when the 9th Division conducted simultaneous assaults in north-west Labuan and on the coast of Brunei. While Brunei was quickly secured, the Japanese garrison on Labuan held out for over a week. After the Brunei Bay region was secured the 24th Brigade was landed in North Borneo and the 20th Brigade advanced along the western coast of Borneo south from Brunei. Both brigades rapidly advanced against weak Japanese resistance and most of north-west Borneo was liberated by the end of the war.[165] During the campaign the 9th Division was assisted by indigenous fighters who were waging a guerrilla war against Japanese forces with the support of Australian special forces such as Z Special Unit.[166]

The third and final stage of the campaign was the capture of Balikpapan on the central east coast of Borneo. This operation had been opposed by Blamey, who believed that it was unnecessary, but went ahead on the orders of MacArthur. After a 20-day preliminary air and naval bombardment the 7th Division landed near the town on 1 July. Balikpapan and its surrounds were secured after some heavy fighting on 21 July but mopping up continued until the end of the war as isolated pockets of Japanese resistance remained. The capture of Balikpapan was the last large-scale land operation conducted by the Western Allies during World War II.[167] Although the Borneo campaign was criticised in Australia at the time, and in subsequent years, as pointless or a waste of soldiers' lives, it did achieve a number of objectives, such as increasing the isolation of significant Japanese forces occupying the main part of the NEI, capturing major oil supplies and freeing Allied prisoners of war, who were being held in deteriorating conditions.[168]

Post-war years[]

Prior to the end of the war on 15 August 1945, the Australian military was preparing to contribute forces to the invasion of Japan. Australia's participation in this operation would have involved elements of all three services fighting as part of Commonwealth forces. It was planned to form a new 10th Division from existing AIF personnel which would form part of the Commonwealth Corps with British, Canadian and New Zealand units. The corps' organisation was to be identical to that of a US Army corps, and it would have participated in the invasion of the Japanese home island of Honshū which was scheduled for March 1946 under Operation Coronet.[169] Planning for operations against Japan ceased in August 1945 when Japan surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[170] Japanese field commanders subsequently surrendered to Allied forces across the Pacific Theatre and Australian forces accepted the surrender of their Japanese opponents at ceremonies conducted at Morotai, several locations in Borneo, Timor, Wewak, Rabaul, Bougainville and Nauru.[171] Following the surrender the Australian Army faced a number of immediate operational and administrative issues, including the need to maintain security in the areas it occupied, the disarming and administration of surrendered Japanese forces in these areas, organising the return of approximately 177,000 soldiers (including prisoners of war) to Australia, the demobilisation and discharge of the bulk of the soldiers serving in the Army, and the raising of an occupation force for service in Japan.[172]

Australian Army units were deployed as occupation forces following the Japanese surrender. Under the terms of an agreement reached between Blamey and Admiral Louis Mountbatten, the head of South East Asia Command, Australia was responsible for providing occupation forces for all of Borneo, the NEI east of Lombok (including western New Guinea) and the pre-war Australian and British territories in eastern New Guinea and the Solomon Islands as well as Nauru and Ocean Islands in the Pacific. The Australian forces in Borneo and the NEI were to remain in place only until they were relieved by British and Dutch units in late 1945.[173] I Corps was responsible for garrisoning Borneo and the eastern NEI, and the First Army disarmed Japanese forces in the pre-war British and Australian territories in and around New Guinea.[174] After the surrender documents were signed the 7th and 9th Divisions took control of Borneo and five forces were dispatched from Morotai and Darwin to the key islands in the eastern NEI.[175] While the British forces in the western NEI took part in fighting against Indonesian nationalists, the Australians were careful to not become involved in the Indonesian National Revolution and sought to hand control of their occupation zones to the Netherlands Indies Civil Administration as quickly as possible.[176] Relations between the Australian troops and Indonesians were generally good, due in part to the decision by the Waterside Workers' Federation of Australia to not load Dutch ships which were carrying military supplies bound for the NEI.[177] The last Australian occupation troops left the NEI in February 1946.[178]

The Australian Army also contributed troops to the British Commonwealth Occupation Force (BCOF) in Japan. Volunteers for this force were recruited in late 1945, with most being assigned to three new infantry battalions: the 65th Battalion was formed from volunteers from the 7th Division, the 66th Battalion by men from the 6th Division and the 67th from 9th Division personnel.[179] These and other units were grouped at Morotai as the 34th Brigade in October 1945. The brigade's departure for Japan was delayed until February 1946 by inter-Allied negotiations, but it eventually took over responsibility for enforcing the terms of the Japanese surrender in Hiroshima Prefecture.[180][181] The three infantry battalions raised for occupation duties were designated the 1st, 2nd and 3rd battalions of the Royal Australian Regiment in 1949,[182] and the 34th Brigade became the 1st Brigade when it returned to Australia in December 1948, forming the basis of the post-war Regular Army. From that time the Australian Army contribution to the occupation of Japan was reduced to a single under-strength battalion. Australian forces remained until September 1951 when the BCOF ceased operations, although by the time the majority of units had been committed to the fighting on the Korean peninsula following the outbreak of the Korean War on 25 June 1950.[183]

Leadership[]

When the war began the Army was on the cusp of a generational change. At the time, the senior officers on the active list were Major Generals Gordon Bennett and Thomas Blamey, although Bennett had not held an appointment for seven years and Blamey for the last two. Then came the Chief of the General Staff, Major General John Lavarack; the Adjutant General, Major General Sir Carl Jess; Major General , the Quartermaster General; Major General Edmund Drake-Brockman, the commander of the 3rd Division; and Major General Iven Mackay, the commander 2nd Division. All were over 50 years of age and all except Bennett, Drake-Brockman and Mackay were serving or former regular soldiers. Only the first three were considered to command the 6th Division and Second AIF, for which posts Blamey was selected by Prime Minister Menzies. Both Blamey and Lavarack were promoted to lieutenant general on 13 October 1939.[184] Blamey was subsequently appointed General Officer Commanding (GOC) I Corps following its raising in March 1940, while Mackay was appointed to succeed him in command of the 6th Division and Lavarack assumed command of the newly formed 7th Division.[27][185]

The next most senior regular officers, all colonels, included men like Vernon Sturdee, Henry Wynter and John Northcott, all of whom had joined the Army before World War I. These officers held senior commands throughout the war, but seldom active ones. Below them were a distinct group of regular officers, graduates of the Royal Military College, Duntroon, which had opened in 1911. Their number included Frank Berryman, William Bridgeford, Cyril Clowes, Horace Robertson, Sydney Rowell and George Alan Vasey. These officers had fought in World War I and reached the rank of major, but their promotion prospects were restricted and they remained majors for twenty years. Many left the Army to join the British or Indian armies, or the RAAF, or to return to civilian life. As a group, they had become embittered and resentful, and determined to prove that they could lead troops in battle.[186] Many regular officers had attended training courses or been on exchange with the British Army, which was important in the early years of the war when there was close cooperation between the two armies.[187]

Between the wars, the reservists enjoyed much better promotion prospects. While Alan Vasey, a major in the First AIF, was not promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel until 1937, Kenneth Eather, a reservist who was too young to serve in World War I, was commissioned in 1923 and promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1935. Menzies ordered that all commands in the 6th Division be given to reservists rather than regular officers,[188] who had become political adversaries through their outspoken opposition to the Singapore strategy.[189] Appointments therefore went to reservists like Stanley Savige, Arthur Allen, Leslie Morshead and Edmund Herring.[190] Later other Militia officers rose to prominence as brigade and division commanders. The distinguished records of officers like Heathcote Hammer,[191] Ivan Dougherty,[192] David Whitehead, Victor Windeyer and Selwyn Porter would challenge the regular officers' contention that they had a special claim to senior command ability.[193][194]

At the start of the war, the majority of battalion commands went to older reservists, many of whom had commanded battalions or served in the First AIF. As the war went on, the average age of battalion commanders declined from 42.9 years old in 1940 to 35.6 in 1945.[195] The prevalence of regular officers in senior positions also rose, and in 1945 they held half of all senior appointments. They remained under-represented in unit commands,[196] and, as in 1940, there was still only one infantry battalion commanded by a regular officer.[195] Following the outbreak of war with Japan, many senior officers with distinguished records in the Middle East were recalled to Australia to lead Militia formations and fill important staff posts as the Army expanded.[197] The following year, though, the Army reached its greatest extent after which it shrank in size. With a limited number of senior appointments and more senior officers than required, Blamey faced public and political criticism after he "shelved" several senior officers.[198] The career prospects of junior officer were also affected, particularly in the infantry. Of the 52 officers promoted to the substantive rank of lieutenant colonel in the last six months of 1944 only five were infantrymen, while two were engineers, and 45 were from the supporting arms.[40]

Meanwhile, the return of the AIF divisions to Australia from the Middle East in 1942 coincided with the arrival of large numbers of American troops, including the US 32nd and 41st Infantry Divisions. From April 1942 MacArthur took over command of all US and Australian forces in the newly formed South West Pacific Area as Supreme Commander.[121] Blamey had been appointed Commander-in-Chief AMF in March following his promotion to general, setting up Land Headquarters to subsume the role of the Military Board, which was suspended on 30 July.[199][200][Note 1] As Commander-in-Chief AMF he reported directly to MacArthur and was subsequently also given command of Allied Land Forces in the theatre. Yet although Australian forces made up the bulk of the Allied forces in SWPA until 1944 in practice for political reasons MacArthur ensured that Blamey only commanded Australian forces, while he also limited the number of Australian staff officers posted to General Headquarters, and they remained underrepresented for the remainder of the war.[121]

Equipment[]

The Australian Army generally had a long-standing policy of using British-designed equipment, but equipment from Australia, the United States and some other countries was introduced into service in the war's later years.[202] Pre-war defence policies favoured the RAN, which received the majority of defence spending in the interwar period.[203] The result was that when war came in 1939, the Army's equipment was of World War I vintage, and Australian factories were only capable of producing small arms. Most equipment was obsolescent and had to be replaced, and new factories were required to produce the latest weapons, equipment and motor vehicles. Some 2,860 motor vehicles and motorcycles suitable for military use were purchased in 1939 for the Militia and another 784 for the 6th Division, but since a division's war establishment was around 3,000, this was only enough for training. In February 1940, the Treasury urged the War Cabinet to slow orders of motor vehicles to save the shipping space used for sending them to the Middle East for wheat cargoes.[204]