Singapore strategy

The Singapore strategy was a naval defence policy of the British Empire that evolved in a series of war plans from 1919 to 1941. It aimed to deter aggression by the Empire of Japan by providing for a base for a fleet of the Royal Navy in the Far East, able to intercept and defeat a Japanese force heading south towards India or Australia. To be effective it required a well-equipped base; Singapore, at the eastern end of the Strait of Malacca, was chosen in 1919 as the location of this base; work continued on this naval base and its defences over the next two decades.

The planners envisaged that a war with Japan would have three phases: while the garrison of Singapore defended the fortress, the fleet would make its way from home waters to Singapore, sally to relieve or recapture Hong Kong, and blockade the Japanese home islands to force Japan to accept terms. The idea of invading Japan was rejected as impractical, but British planners did not expect that the Japanese would willingly fight a decisive naval battle against the odds. Aware of the impact of a blockade on an island nation at the heart of a maritime empire, they felt that economic pressure would suffice.

The Singapore strategy was the cornerstone of British Imperial defence policy in the Far East during the 1920s and 1930s. By 1937, according to Captain Stephen Roskill, "the concept of the 'Main Fleet to Singapore' had, perhaps through constant repetition, assumed something of the inviolability of Holy Writ".[1] A combination of financial, political and practical difficulties ensured that it could not be successfully implemented. During the 1930s, the strategy came under sustained criticism in Britain and abroad, particularly in Australia, where the Singapore strategy was used as an excuse for parsimonious defence policies. The strategy ultimately led to the despatch of Force Z to Singapore and the sinking of the Prince of Wales and Repulse by Japanese air attack on 10 December 1941. The subsequent ignominious fall of Singapore was described by Winston Churchill as "the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history".[2]

Origins[]

After the First World War, the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet that had challenged the Royal Navy for supremacy was scuttled in Scapa Flow, but the Royal Navy was already facing serious challenges to its position as the world's most powerful fleet from the United States Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy.[3] The United States' determination to create what Admiral of the Navy George Dewey called "a navy second to none" presaged a new maritime arms race.[4]

The U.S. Navy was smaller than the Royal Navy in 1919, but ships laid down under its wartime construction program were still being launched, and their more recent construction gave the American ships a technological edge.[5] The "two-power standard" of 1889 called for a Royal Navy strong enough to take on any two other powers. In 1909, this was scaled back to a policy of 60% superiority in dreadnoughts.[6] Rising tensions over the U.S. Navy's building program led to heated arguments between the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Rosslyn Wemyss, and the Chief of Naval Operations Admiral William S. Benson in March and April 1919,[7] although, as far back as 1909, the government directed that the United States was not to be regarded as a potential enemy. This decision was reaffirmed by Cabinet in August 1919 in order to preclude the U.S. Navy's building program from becoming a justification for the Admiralty initiating one of its own.[8] In 1920, the First Lord of the Admiralty Sir Walter Long announced a "one-power standard", under which the policy was to maintain a navy "not ... inferior in strength to the Navy of any other power".[6] The one-power standard became official when it was publicly announced at the 1921 Imperial Conference.[9] The Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 reinforced this policy.

The Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom and the Dominions met at the 1921 Imperial Conference to determine a unified international policy, particularly the relationship with the United States and Japan.[10] The most urgent issue was that of whether or not to renew the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, which was due to expire on 13 July 1921.[11] On one side were the Prime Minister of Australia Billy Hughes and the Prime Minister of New Zealand Bill Massey, who strongly favoured its renewal.[12] Neither wanted their countries to be caught up in a war between the United States and Japan, and contrasted the generous assistance that Japan rendered during the First World War with the United States' disengagement from international affairs in its aftermath.[13] "The British Empire", declared Hughes, "must have a reliable friend in the Pacific".[14] They were opposed by the Prime Minister of Canada, Arthur Meighen, on the grounds that the alliance would adversely affect the relationship with the United States, which Canada depended upon for its security.[15] As a result, no decision to renew was reached, and the alliance was allowed to expire.[16]

The Washington Naval Treaty in 1922 provided for a 5:5:3 ratio of capital ships of the British, United States and Japanese navies.[17] Throughout the 1920s, the Royal Navy remained the world's largest navy, with a comfortable margin of superiority over Japan, which was regarded as the most likely adversary.[18] The Washington Naval Treaty also prohibited the fortification of islands in the Pacific, but Singapore was specifically excluded.[17] The provisions of the London Naval Treaty of 1930, however, restricted naval construction, resulting in a serious decline in the British shipbuilding industry.[19] Germany's willingness to limit the size of its navy led to the Anglo-German Naval Agreement of 1935. This was seen as signalling a sincere desire to avoid conflict with Britain.[20] In 1934, the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Ernle Chatfield, began to press for a new naval build-up sufficient to fight both Japan and the strongest European power. He intended to accelerate construction to the maximum capacity of the shipyards,[21] but the Treasury soon became alarmed at the potential cost of the program, which was costed at between £88 and £104 million.[22] By 1938, the Treasury was losing its fight to stop rearmament; politicians and the public were more afraid of being caught unprepared for war with Germany and Japan than of a major financial crisis in the more distant future.[23]

Plans[]

The Singapore strategy was a series of war plans that evolved over a twenty-year period in which the basing of a fleet at Singapore was a common but not a defining aspect. Plans were crafted for different contingencies, both defensive and offensive. Some were designed to defeat Japan, while others were merely to deter aggression.[24]

In November 1918, the Australian Minister for the Navy, Sir Joseph Cook, had asked Admiral Lord Jellicoe to draw up a scheme for the Empire's naval defence. Jellicoe set out on a tour of the Empire in the battlecruiser HMS New Zealand in February 1919.[25] He presented his report to the Australian government in August 1919. In a section of the report classified as secret, he advised that the interests of the British Empire and Japan would inevitably clash. He called for the creation of a British Pacific Fleet strong enough to counter the Imperial Japanese Navy, which he believed would require 8 battleships, 8 battlecruisers, 4 aircraft carriers, 10 cruisers, 40 destroyers, 36 submarines and supporting auxiliaries.[5]

Although he did not specify a location, Jellicoe noted that the fleet would require a major dockyard somewhere in the Far East. A paper entitled "The Naval Situation in the Far East" was considered by the Committee of Imperial Defence in October 1919. In this paper the naval staff pointed out that maintaining the Anglo-Japanese Alliance might lead to war between the British Empire and the United States. In 1920, the Admiralty issued War Memorandum (Eastern) 1920, a series of instructions in the event of a war with Japan. In it, the defence of Singapore was described as "absolutely essential".[5] The strategy was presented to the Dominions at the 1923 Imperial Conference.[26]

The authors of War Memorandum (Eastern) 1920 divided a war with Japan into three phases. In the first phase, the garrison of Singapore would defend the fortress while the fleet made its way from home waters to Singapore. Next, the fleet would sail from Singapore and relieve or recapture Hong Kong. The final phase would see the fleet blockade Japan and force it to accept terms.[27]

Most planning focused on the first phase, which was seen as the most critical. This phase involved construction of defence works for Singapore. For the second phase, a naval base capable of supporting a fleet was required. While the United States had constructed a graving dock capable of taking battleships at Pearl Harbor between 1909 and 1919, the Royal Navy had no such base east of Malta.[5] In April 1919, the Plans Division of the Admiralty produced a paper which examined possible locations for a naval base in the Pacific in case of a war with the United States or Japan. Hong Kong was considered but regarded as too vulnerable, while Sydney was regarded as secure but too far from Japan. Singapore emerged as the best compromise location.[25]

The estimate of how long it would take for the fleet to reach Singapore after the outbreak of hostilities varied. It had to include the time required to assemble the fleet, prepare and provision its ships, and then sally to Singapore. Initially, the estimate was 42 days, assuming reasonable advance warning. In 1938, it was increased to 70 days, with 14 more for reprovisioning. It was further increased in June 1939 to 90 days plus 15 for reprovisioning, and finally, in September 1939, to 180 days.[28]

To facilitate this movement, a series of oil storage facilities were constructed at Gibraltar, Malta, Port Said, Port Sudan, Aden, Colombo, Trincomalee, Rangoon, Singapore, and Hong Kong.[29] A complicating factor was that the battleships could not traverse the Suez Canal fully laden, so they would have to refuel on the other side.[30] Singapore was to have storage for 1,250,000 long tons (1,270,000 t) of oil.[31] Secret bases were established at Kamaran Bay, Addu Atoll and Nancowry.[32] It was estimated that the fleet would require 110,000 long tons (110,000 t) of oil per month, which would be transported in 60 tankers.[33] Oil would be shipped in from the refineries at Abadan and Rangoon, supplemented by buying up the entire output of the Netherlands East Indies.[34]

The third phase received the least consideration, but naval planners were aware that Singapore was too far from Japan to provide an adequate base for operations close to Japan. Moreover, the further the fleet proceeded from Singapore, the weaker it would become.[27] If American assistance was forthcoming, there was the prospect of Manila being used as a forward base.[35] The idea of invading Japan and fighting its armies on its own soil was rejected as impractical, but the British planners did not expect that the Japanese would willingly fight a decisive naval battle against the odds. They were therefore drawn to the concept of a blockade. From personal experience they were aware of the impact it could have on an island nation at the heart of a maritime empire, and felt that economic pressure would suffice.[27]

Japan's vulnerability to blockade was studied. Using information supplied by the Board of Trade and the naval attaché in Tokyo, the planners estimated that the British Empire accounted for around 27 per cent of Japan's imports. In most cases these imports could be replaced from sources in China and the United States. However, certain critical materials for which Japan relied heavily on imports were identified, including metals, machinery, chemicals, oil and rubber,[36] and many of the best sources of these were under British control. Japan's access to neutral shipping could be restricted by refusing insurance to ships trading with Japan, and chartering ships to reduce the number available.[37]

The problem with enforcing a close blockade with ships was that warships loitering off the coast of Japan would be vulnerable to attack by aircraft and submarines.[38] Blockading Japanese ports with small ships was a possibility, but this would first require the destruction or neutralisation of the Japanese fleet, and it was far from certain that the Japanese fleet would place itself in a position where it could be destroyed. A plan was adopted for a more distant blockade, whereby ships bound for Japan would be intercepted as they passed through the East Indies or the Panama Canal. This would not cut off Japan's trade with China or Korea, and probably not with the United States either. The effectiveness of such a blockade was therefore questionable.[36]

Rear Admiral Sir Herbert Richmond, the Commander in Chief, East Indies Station, noted that the logic was suspiciously circular:

- We are going to force Japan to surrender by cutting off her essential supplies.

- We cannot cut off her essential supplies until we defeat her fleet.

- We cannot defeat her fleet if it will not come out to fight.

- We shall force it to come out to fight by cutting off her essential supplies.[39]

The 1919 plans incorporated a Mobile Naval Base Defence Organisation (MNBDO) which could develop and defend a forward base.[40] The MNBDO had a strength of 7,000 and included a brigade of antiaircraft artillery, a brigade of coastal artillery and a battalion of infantry, all drawn from the Royal Marines.[41] In one paper exercise, the Royal Marines occupied Nakagusuku Bay unopposed and the MNBDO developed a major base there from which the fleet blockaded Japan. Actual fleet exercises were conducted in the Mediterranean in the 1920s to test the MNBDO concept.[42] However, the Royal Marines were not greatly interested in amphibious warfare, and lacking organisational backing, the techniques and tactics of amphibious warfare began to atrophy. By the 1930s the Admiralty was concerned that the United States and Japan were well ahead of Britain in this field and persuaded the Army and RAF to join with it in establishing the Inter-Service Training and Development Centre, which opened in July 1938. Under its first commandant, Captain Loben Edward Harold Maund, it began investigating the problems of amphibious warfare, including the design of landing craft.[43]

Nor was this the only field in which the Royal Navy was lagging in the 1930s. In the 1920s, Colonel the Master of Sempill led the semi-official Sempill Mission to Japan to help the Imperial Japanese Navy establish an air arm.[44] At the time the Royal Navy was the world leader in naval aviation. The Sempill mission taught advanced techniques such as carrier deck landing, conducted training with modern aircraft, and provided engines, ordnance and technical equipment.[45] Within a decade, Japan had overtaken Britain.[46] The Royal Navy pioneered the armoured flight deck, which enabled carriers to absorb damage, but resulted in limiting the number of aircraft that a carrier could operate.[47] The Royal Navy had great faith in the ability of ships' antiaircraft batteries, and so saw little need for high performance fighters.[48] To maximise the benefit of the small numbers of aircraft that could be carried, the Royal Navy developed multi-role aircraft such as the Blackburn Roc, Fairey Fulmar, Fairey Barracuda, Blackburn Skua and Fairey Swordfish. As a result, the Royal Navy's aircraft were no match for their Japanese counterparts.[49]

The possibility of Japan taking advantage of a war in Europe was foreseen. In June 1939, the Tientsin Incident demonstrated another possibility: that Germany might attempt to take advantage of a war in the Far East.[50] In the event of a worst-case scenario of simultaneous war with Germany, Italy and Japan, two approaches were considered. The first was to reduce the war to one against Germany and Japan only by knocking Italy out of the conflict as quickly as possible.[51] The former First Sea Lord, Sir Reginald Drax, who was brought out of retirement to advise on strategy, called for a "flying squadron" of four or five battleships, along with an aircraft carrier, some cruisers and destroyers, to be sent to Singapore. Such a force would be too small to fight the Japanese main fleet, but could protect British trade in the Indian Ocean against commerce raiders. Drax argued that a small, fast force would be better in this role than a large, slow one. When more ships became available, it could become the nucleus of a full-sized battle fleet. Chatfield, now Minister for Coordination of Defence, disagreed with this concept. He felt that the flying squadron would become nothing more than a target for the Japanese fleet. Instead, he put forward a second approach, namely that the Mediterranean be abandoned and the fleet sent to Singapore.[52]

Base development[]

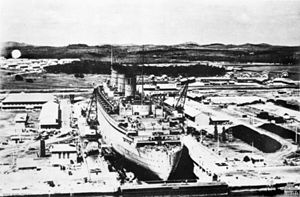

Following surveys, a site at Sembawang was chosen for a naval base.[53] The Straits Settlements made a free gift of 2,845 acres (1,151 ha) of land for the site,[54] and a sum of £250,000 for construction of the base was donated by Hong Kong in 1925. That exceeded the United Kingdom's contribution that year of £204,000 towards the floating dock.[55] Another £2,000,000 was paid by the Federated Malay States, while New Zealand donated another £1,000,000.[56] The contract for construction of the naval dockyard was awarded to the lowest bidder, Sir John Jackson Limited, for £3,700,000.[57] Some 6,000,000 cubic yards (4,600,000 m3) of earth were moved to level the ground, and 8,000,000 cubic yards (6,100,000 m3) of marsh was filled in. The floating dock was constructed in England and towed to Singapore by Dutch tugboats. It was 1,000 feet (300 m) long and 1,300 feet (400 m) wide, making it one of the largest in the world. There would be 5,000 feet (1,500 m) of deep water quays, and supporting infrastructure including warehouses, workshops and hospitals.[58]

To defend the naval base, heavy 15-inch naval guns (381.0 mm) were stationed at Johore battery, Changi, and at Buona Vista to deal with battleships. Medium BL 9.2 inch guns (233.7 mm) were provided for dealing with smaller attackers. Batteries of smaller calibre anti-aircraft guns and guns for dealing with raids were located at Fort Siloso, Fort Canning and Labrador.[59] The five 15-inch guns were all surplus Navy guns, manufactured between 1903 and 1919.[60] Part of their cost was met from a gift of £500,000 from Sultan Ibrahim of Johor for the Silver Jubilee of the coronation King George V. Three of the guns were given an all-round (360°) traverse and subterranean magazines.[61]

Aviation was not neglected. Plans called for an air force of 18 flying boats, 18 reconnaissance fighters, 18 torpedo bombers and 18 single-seat fighters to protect them. Royal Air Force airfields were established at RAF Tengah and RAF Sembawang.[62] The Chief of the Air Staff, Air Marshal Lord Trenchard, argued that 30 torpedo bombers could replace the 15-inch guns. The First Sea Lord, Admiral of the Fleet Lord Beatty, did not agree. A compromise was reached whereby the guns would be installed, but the issue was reconsidered when better torpedo planes became available.[63] Test firings of 15-inch and 9.2-inch guns at Malta and Portsmouth in 1926 indicated that greatly improved shells were required if the guns were to have a chance of hitting a battleship.[64]

The King George VI dry dock was formally opened by the Governor of the Straits Settlements, Sir Shenton Thomas, on 14 February 1938. Two squadrons of the Fleet Air Arm provided a flypast. The 42 vessels in attendance included three US Navy cruisers. The presence of this fleet gave an opportunity to conduct a series of naval, air and military exercises. The aircraft carrier HMS Eagle was able to sail undetected to within 135 miles (217 km) of Singapore and launch a series of surprise raids on the RAF airfields. The local air commander, Air Vice-Marshal Arthur Tedder, was greatly embarrassed. The local land commander, Major-General Sir William Dobbie, was no less disappointed by the performance of the anti-aircraft defences. Reports recommended the installation of radar on the island, but this was not done until 1941. The naval defences worked better, but a landing party from HMS Norfolk was still able to capture the Raffles Hotel. What most concerned Dobbie and Tedder was the possibility of the fleet being bypassed entirely by an overland invasion of Malaya from Thailand. Dobbie conducted an exercise in southern Malaya which demonstrated that the jungle was far from impassable. The Chiefs of Staff Committee concluded that the Japanese would most likely land on the east coast of Malaya and advance on Singapore from the north.[65]

Australia[]

In Australia the conservative Nationalist Party government of Stanley Bruce latched onto the Singapore strategy, which called for reliance on the British navy, supported by a naval squadron as strong as Australia could afford. Between 1923 and 1929, £20,000,000 was spent on the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), while the Australian Army and the munitions industry received only £10,000,000 and the fledgling Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) just £2,400,000.[66] The policy had the advantage of pushing responsibility for Australian defence onto Britain. Unlike New Zealand, Australia declined to contribute to the cost of the base at Singapore.[67] In petitioning a parsimonious government for more funds, the Australian Army had to refute the Singapore strategy, "an apparently well-argued and well-founded strategic doctrine that had been endorsed at the highest levels of imperial decision-making".[68]

An alternative policy was put forward in 1923 by the Australian Labor Party, which was in opposition for all but two years of the 1920s and 1930s. It called for Australia's first line of defence to be a powerful air arm, supported by a well-equipped Australian Army that could be rapidly expanded to meet an invasion threat. This, in turn, required a strong munitions industry. Labor politicians cited critics like Rear Admiral William Freeland Fullam, who drew attention to the vulnerability of warships to aircraft, naval mines and submarines. The Labor Party's Albert Green noted in 1923 that when a battleship of the day cost £7,000,000 while an aircraft cost £2,500, there was a genuine cause for concern as to whether the battleship was a better investment than hundreds of aircraft, if the aircraft could sink battleships.[69] The Labor Party's policy became indistinguishable from the Army's position.[66]

In September 1926, Lieutenant Colonel Henry Wynter gave a lecture to the United Services Institute of Victoria entitled "The Strategical Inter-relationship of the Navy, the Army and the Air Force: an Australian View", which was published in the April 1927 edition of British Army Quarterly. In this article Wynter argued that war was most likely to break out in the Pacific at a time when Britain was involved in a crisis in Europe, which would prevent Britain from sending sufficient resources to Singapore. He contended that Singapore was vulnerable, especially to attack from the land and the air, and argued for a more balanced policy of building up the Army and RAAF rather than relying on the RAN.[66] "Henceforward", wrote Australian official historian Lionel Wigmore, "the attitude of the leading thinkers in the Australian Army towards British assurances that an adequate fleet would be sent to Singapore at the critical time was (bluntly stated): 'We do not doubt that you are sincere in your beliefs but, frankly, we do not think you will be able to do it.'"[70]

Frederick Shedden wrote a paper putting the case for the Singapore strategy as a means of defending Australia. He argued that since Australia was also an island nation, it followed that it would also be vulnerable to a naval blockade. If Australia could be defeated without an invasion, the defence of Australia had to be a naval one. Colonel John Lavarack, who had attended the Imperial Defence College class of 1928 with Shedden, disagreed. Lavarack responded that the vast coastline of Australia would make a naval blockade very difficult, and its considerable internal resources meant that it could resist economic pressure.[71] When Richmond attacked the Labor Party's position in an article in British Army Quarterly in 1933, Lavarack wrote a rebuttal.[72] In 1936, the leader of the opposition John Curtin read an article by Wynter in the House of Representatives. Wynter's outspoken criticism of the Singapore strategy led to his transfer to a junior post.[72] Soon after the outbreak of war with Germany on 3 September 1939,[73] Prime Minister Robert Menzies appointed a British officer, Lieutenant General Ernest Squires, to replace Lavarack as Chief of the General Staff. Within months, the Chief of the Air Staff was replaced with a British officer as well.[74]

New Zealand[]

Successive New Zealand governments—the Reform Government of 1912–1928, United Government in 1928–1931, United-Reform Coalition Government of 1931–1935, and the First Labour Government in 1935–1949—all supported the Singapore Strategy. The New Zealand financial contribution was eight annual payments of £125,000, a million pounds in total,[75] rather than the £225,000 annually proposed by the Admiralty.[76] Expansion of the New Zealand Devonport Naval Base was also proposed, and in 1926 the alternative of a third cruiser was considered. Labour, on coming to power in 1935, gave more importance to a local air force,[77] though later Walter Nash accepted the need to keep sea lanes open.[78] There was little liaison with Australia; in 1938 New Zealand Chiefs of Staff papers were sent to London but not Australia.[79] But by 1936 New Zealand military confidence in the Singapore Strategy was waning; with the possibility of Italy as well as Germany and Japan as enemies, in seemed likely that Britain would also be committed in the Mediterranean.[80]

Second World War[]

With war with Germany now a reality, Menzies sent Richard Casey to London to seek reassurances about the defence of Australia in the event that Australian forces were sent to Europe or the Middle East.[81] In November 1939, Australia and New Zealand were given reassurances that Singapore would not be allowed to fall, and that in the event of war with Japan, the defence of the Far East would take priority over the Mediterranean.[82] This seemed possible as the Kriegsmarine, the German navy, was relatively small and France was an ally.[50] Bruce, now Australian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, and Casey met with British Cabinet ministers on 20 November and left with the impression that, despite the reassurances, the Royal Navy was not strong enough to deal with simultaneous crises in Europe, the Mediterranean and the Far East.[83]

During 1940, the situation slowly but inexorably slid towards a worst-case scenario. In June, Italy joined the war on Germany's side and France was knocked out.[84] The Chiefs of Staff Committee now reported:

The security of our imperial interests in the Far East lies ultimately in our ability to control sea communications in the south-western Pacific, for which purpose adequate fleet must be based at Singapore. Since our previous assurances in this respect, however, the whole strategic situation has been radically altered by the French defeat. The result of this has been to alter the whole of the balance of naval strength in home waters. Formerly we were prepared to abandon the Eastern Mediterranean and dispatch a fleet to the Far East, relying on the French fleet in the Western Mediterranean to contain the Italian fleet. Now if we move the Mediterranean fleet to the Far East there is nothing to contain the Italian fleet, which will be free to operate in the Atlantic or reinforce the German fleet in home waters, using bases in north-west France. We must therefore retain in European waters sufficient naval forces to watch both the German and Italian fleets, and we cannot do this and send a fleet to the Far East. In the meantime the strategic importance to us of the Far East both for Empire security and to enable us to defeat the enemy by control of essential commodities at the source has been increased.[85]

There remained the prospect of American assistance. In secret talks in Washington, D.C., in June 1939, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral William D. Leahy raised the possibility of an American fleet being sent to Singapore.[86] In April 1940, the American naval attaché in London, Captain Alan Kirk, approached the Vice Chief of the Naval Staff, Vice-Admiral Sir Thomas Phillips, to ask if, in the event of the United States Fleet being sent to the Far East, the docking facilities at Singapore could be made available, as those at Subic Bay were inadequate. He received full assurances that they would be.[87] Hopes for American assistance were dashed at the staff conference in Washington, D.C., in February 1941. The U.S. Navy was primarily focused on the Atlantic. The American chiefs envisaged relieving British warships in the Atlantic and Mediterranean so a British fleet could be sent to the Far East.[88]

In July 1941, the Japanese occupied Cam Ranh Bay, which the British fleet had hoped to use on its northward drive. This put the Japanese uncomfortably close to Singapore.[89] As diplomatic relations with Japan worsened, in August 1941, the Admiralty and the Chiefs of Staff began considering what ships could be sent. The Chiefs of Staff decided to recommend sending HMS Barham to the Far East from the Mediterranean, followed by four Revenge-class battleships that were refitting at home and in the United States, but Barham was sunk by a German U-boat in November 1941. Three weeks later the remaining two battleships at Alexandria, HMS Queen Elizabeth and Valiant were seriously damaged by Italian human torpedoes. While no more destroyers or cruisers were available, the Admiralty decided that an aircraft carrier, the small HMS Eagle could be sent.[90]

Winston Churchill, now the Prime Minister, noted that since the German battleship Tirpitz was tying up a superior British fleet, a small British fleet at Singapore might have a similar disproportionate effect on the Japanese. The Foreign Office expressed the opinion that the presence of modern battleships at Singapore might deter Japan from entering the war.[91] In October 1941, the Admiralty therefore ordered HMS Prince of Wales to depart for Singapore, where it would be joined by HMS Repulse.[90] The carrier HMS Indomitable was to join them, but it ran aground off Jamaica on 3 November, and no other carrier was available.[92]

In August 1940, the Chiefs of Staff Committee reported that the force necessary to hold Malaya and Singapore in the absence of a fleet was 336 first-line aircraft and a garrison of nine brigades. Churchill then sent reassurances to the prime ministers of Australia and New Zealand that, if they were attacked, their defence would be a priority second only to that of the British Isles.[93] A defence conference was held in Singapore in October 1940. Representatives from all three services attended, including Vice-Admiral Sir Geoffrey Layton (Commander in Chief, China Station); the General Officer Commanding Malaya Command, Lieutenant General Lionel Bond; and Air Officer Commanding the RAF in the Far East, Air Marshal John Tremayne Babington. Australia was represented by its three deputy service chiefs, Captain Joseph Burnett, Major General John Northcott and Air Commodore William Bostock. Over ten days, they discussed the situation in the Far East. They estimated that the air defence of Burma and Malaya would require a minimum of 582 aircraft.[94] By 7 December 1941, there were only 164 first-line aircraft on hand in Malaya and Singapore, and all the fighters were the obsolete Brewster F2A Buffalo.[95] The land forces situation was not much better. There were only 31 battalions of infantry of the 48 required, and instead of two tank regiments, there were no tanks at all. Moreover, many of the units on hand were poorly trained and equipped. Yet during 1941 Britain had sent 676 aircraft and 446 tanks to the Soviet Union.[96]

The Japanese were aware of the state of the Singapore defences. There were spies in Singapore, such as Captain Patrick Heenan, and a copy of the Chiefs of Staff's August 1940 appreciation was among the secret documents captured by the German surface raider Atlantis from the SS Automedon on 11 November 1940. The report was handed over to the Japanese, and the detailed knowledge of Singapore's defences thus obtained may have encouraged the Japanese to attack.[97]

On 8 December 1941, the Japanese occupied the Shanghai International Settlement. A couple of hours later, landings began at Kota Bharu in Malaya. An hour after that, the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor.[98] On 10 December, Prince of Wales and Repulse, sailing to meet the Malaya invasion force, were sunk by Japanese air attack.[99] After the disastrous Malayan Campaign, Singapore surrendered on 15 February 1942.[100] During the final stages of the campaign, the 15-inch and 9.2-inch guns had bombarded targets at Johor Bahru, RAF Tengah and Bukit Timah.[101]

Aftermath[]

Fall of Singapore[]

The fall of Singapore was described by Winston Churchill as "the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history".[2] It was a profound blow to the prestige and morale of the British Empire. The promised fleet had not been sent, and the fortress that had been declared "impregnable" had been quickly captured.[82] Nearly 139,000 troops were lost, of whom about 130,000 were captured. The 38,000 British casualties included most of the British 18th Infantry Division, which had been ordered to Malaya in January. There were also 18,000 Australian casualties, including most of the Australian 8th Division, and 14,000 local troops; but the majority of the defenders—some 67,000 of them—were from British India.[102] About 40,000 of the Indian prisoners of war subsequently joined the Japanese-sponsored Indian National Army.[103]

Richmond, in a 1942 article in The Fortnightly Review, charged that the loss of Singapore illustrated "the folly of not providing adequately for the command of the sea in a two-ocean war".[104] He now argued that the Singapore strategy had been totally unrealistic. Privately he blamed politicians who had allowed Britain's sea power to be run down.[104] The resources provided for the defence of Malaya were inadequate to hold Singapore, and the manner in which those resources were employed was frequently wasteful, inefficient and ineffective.[105]

The disaster had both political and military dimensions. In Parliament, Churchill suggested that an official inquiry into the disaster should be held after the war.[2] When this wartime speech was published in 1946, the Australian government asked if the British government still intended to conduct the inquiry. The Joint Planning Staff considered the matter, and recommended that no inquiry be held, as it would not be possible to restrict its focus to the events surrounding the fall of Singapore, and it would inevitably have to examine the political, diplomatic and military circumstances of the Singapore strategy over a period of many years. Prime Minister Clement Attlee accepted this advice, and no inquiry was ever held.[106]

In Australia and New Zealand, after years of reassurances, there was a sense of betrayal.[82] According to one historian, "In the end, no matter how you cut it, the British let them down".[107] The defeat would affect politics for decades. In a speech in the Australian House of Representatives in 1992, Prime Minister Paul Keating cited the sense of betrayal

I was told that I did not learn respect at school. I learned one thing: I learned about self-respect and self-regard for Australia—not about some cultural cringe to a country which decided not to defend the Malayan peninsula, not to worry about Singapore and not to give us our troops back to keep ourselves free from Japanese domination. This was the country that you people wedded yourself to, and even as it walked out on you and joined the Common Market, you were still looking for your MBEs and your knighthoods, and all the rest of the regalia that comes with it.[108]

A fleet was necessary for the defeat of Japan and eventually a sizeable one, the British Pacific Fleet, did go to the Far East,[109] where it fought with the United States Pacific Fleet. The closer relations that developed between the two navies prior to the outbreak of war with Japan, and the alliance that developed from it afterwards, became the most positive and strategic legacy of the Singapore strategy.[110]

The Singapore Naval Base suffered little damage in the fighting and became the Imperial Japanese Navy's most important facility outside of the Japanese home islands.[111] The 15-inch guns were sabotaged by the British before the fall of Singapore, and four of them were deemed beyond repair and scrapped by the Japanese.[60] The floating dry dock was scuttled by the British, but raised by the Japanese. It was damaged beyond repair by a raid by Boeing B-29 Superfortresses in February 1945, and ultimately towed out to sea and dumped in 1946.[112] The Royal Navy retook possession of the Singapore base in 1945.[103]

Operation Mastodon[]

In 1958, the Singapore strategy was revived in the form of , a plan to deploy V bombers of RAF Bomber Command equipped with nuclear weapons to Singapore as part of Britain's contribution to the defence of the region under Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO). Once again, there were formidable logistical problems. As the V bombers could not fly all the way to Singapore, a new staging base was developed at RAF Gan in the Maldives. RAF Tengah's runway was too short for V bombers, so RAF Butterworth had to be used until it could be lengthened. The basing of nuclear armed aircraft, and the stockpiling of nuclear weapons without consultation with the local authorities soon ran into political complications.[113]

Mastodon called for the deployment of two squadrons of eight Handley Page Victors to Tengah and one of eight Avro Vulcans to Butterworth. The British nuclear stockpile consisted of only 53 nuclear weapons in 1958, most of which were of the old Blue Danube type, but plans called for 48 of the new, lighter Red Beard tactical nuclear weapons to be stored at Tengah when they became available, so each V bomber could carry two.[114] Up to 48 Red Beards were secretly stowed in a highly secured weapons storage facility at RAF Tengah, between 1962 and 1971, for possible use by the V bomber force detachment and for Britain's military commitment to SEATO.[115]

In the meantime, the Royal Navy deployed the aircraft carrier HMS Victorious with Red Beards and nuclear-capable Supermarine Scimitars to the Far East in 1960.[116] As with the original Singapore strategy, there were doubts as to whether 24 V bombers could be spared in the event of a crisis dire enough to require them,[117] especially after China's acquisition of nuclear weapons in 1964.[118] As the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation heated up in 1963, Bomber Command sent detachments of Victors and Vulcans to the Far East. Over the next three years, four V bombers were permanently stationed there, with squadrons in the United Kingdom rotating detachments. In April 1965, No. 35 Squadron RAF carried out a rapid deployment of its eight Vulcans to RAAF Butterworth and RAF Tengah.[119] Air Chief Marshal Sir John Grandy reported that the V bombers "provided a valuable deterrent to confrontation being conducted on a large scale".[120]

In 1965, racial, political, and personal tensions led to Singapore seceding from Malaysia and becoming an independent country.[121] With the end of the confrontation, the last V bombers were withdrawn in 1966.[120] The following year, the British government announced its intention to withdraw its forces from East of Suez.[122] The Singapore Naval Base was handed over to the government of Singapore on 8 December 1968, and Sembawang Shipyard subsequently became the basis of a successful ship repair industry.[103] The Red Beards were returned to the UK via the US in 1971.[123]

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 214

- ^ a b c Churchill 1950, p. 81

- ^ Callahan 1974, p. 69

- ^ "Urges Navy Second to None: Admiral Dewey and Associates Say Our Fleet Should Equal the Most Powerful in the World" (PDF). New York Times. 22 December 1915. Retrieved 25 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d McIntyre 1979, pp. 19–23

- ^ a b Callahan 1974, p. 74

- ^ Callahan 1974, p. 70

- ^ Bell 2000, p. 49

- ^ Bell 2000, p. 13

- ^ Tate & Foy 1959, p. 539

- ^ Brebner 1935, p. 48

- ^ Brebner 1935, p. 54

- ^ Tate & Foy 1959, pp. 535–538

- ^ Tate & Foy 1959, p. 543

- ^ Brebner 1935, pp. 48–50

- ^ Brebner 1935, p. 56

- ^ a b McIntyre 1979, pp. 30–32

- ^ Bell 2000, pp. 18–20

- ^ Bell 2000, p. 25

- ^ Bell 2000, pp. 103–105

- ^ Bell 2000, pp. 26–28

- ^ Bell 2000, pp. 33–34

- ^ Bell 2000, p. 38

- ^ Bell 2000, p. 60

- ^ a b McIntyre 1979, pp. 4–5

- ^ Dennis 2010, pp. 21–22

- ^ a b c Bell 2001, pp. 608–612

- ^ Paterson 2008, pp. 51–52

- ^ Field 2004, p. 61

- ^ Field 2004, p. 93

- ^ Field 2004, p. 67

- ^ Field 2004, p. 66

- ^ Field 2004, p. 57

- ^ Field 2004, pp. 93–94

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 174

- ^ a b Bell 2000, pp. 76–77

- ^ Bell 2000, pp. 84–85

- ^ Field 2004, p. 75

- ^ Field 2004, pp. 77–78

- ^ Field 2004, p. 59

- ^ Millett 1996, p. 59

- ^ Field 2004, pp. 159–164

- ^ Millett 1996, pp. 61–63

- ^ Phillips, Pearson (6 January 2002). "The Highland peer who prepared Japan for war". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ Ferris 2010, pp. 76–78

- ^ Ferris 2010, p. 80

- ^ Till 1996, pp. 218–219

- ^ Till 1996, p. 217

- ^ Field 2004, p. 153

- ^ a b McIntyre 1979, pp. 156–161

- ^ Bell 2001, pp. 613–614

- ^ Field 2004, pp. 107–111

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 25–27

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 55

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 57–58

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 61–65, 80

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 67

- ^ "Strong gateway". The Cairns Post. Qld.: National Library of Australia. 19 July 1940. p. 8. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 71–73

- ^ a b Bogart, Charles H. (June 1977). "The Fate of Singapore's Guns – Japanese Report". Naval Historical Society of Australia.

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 120–122

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 74

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 75–81

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 83

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 135–137

- ^ a b c Long 1952, pp. 8–9

- ^ Long 1952, p. 10

- ^ Dennis 2010, p. 22

- ^ Gill 1957, pp. 18–19

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 8

- ^ Dennis 2010, pp. 23–25

- ^ a b Long 1952, pp. 19–20

- ^ Long 1952, pp. 33–34

- ^ Long 1952, p. 27

- ^ McGibbon 1981, pp. 168, 224.

- ^ McGibbon 1981, p. 165.

- ^ McGibbon 1981, p. 256.

- ^ McGibbon 1981, pp. 275–276.

- ^ McGibbon 1981, pp. 310–311.

- ^ McGibbon 1981, pp. 279, 292.

- ^ Day 1988, pp. 23–31

- ^ a b c Paterson 2008, p. 32

- ^ Day 1988, p. 31

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 165

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 19

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 156

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 163

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 178–179

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 182

- ^ a b Roskill 1954, pp. 553–559

- ^ Bell 2001, pp. 620–623

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 92

- ^ Callahan 1974, p. 83

- ^ Gillison 1962, pp. 142–143

- ^ Gillison 1962, pp. 204–205

- ^ Wigmore 1957, pp. 102–103

- ^ Hack & Blackburn 2003, pp. 90–91

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 192–193

- ^ Wigmore 1957, p. 144

- ^ Wigmore 1957, pp. 382, 507

- ^ McIntyre 1979, p. 208

- ^ Wigmore 1957, pp. 182–183, 189–190, 382

- ^ a b c McIntyre 1979, p. 230

- ^ a b Bell 2001, pp. 605–606

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 214–216

- ^ Farrell 2010, p. ix

- ^ Murfett 2010, p. 17

- ^ Paul Keating, Prime Minister (27 February 1992). Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Commonwealth of Australia: House of Representatives.

- ^ McIntyre 1979, pp. 221–222

- ^ Kennedy 2010, p. 52

- ^ Cate 1953, p. 156

- ^ "Largest Floating-Dock To Be Dumped". The West Australian. Perth: National Library of Australia. 2 September 1946. p. 9. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ^ Jones 2003, pp. 316–318

- ^ Jones 2003, pp. 320–322

- ^ Tom, Rhodes (31 December 2000). "Britain Kept Secret Nuclear Weapons In Singapore & Cyprus". The Sunday Times. United Kingdom: News International. Archived from the original on 10 June 2001. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ Jones 2003, p. 325

- ^ Jones 2003, p. 329

- ^ Jones 2003, p. 333

- ^ Wynn 1994, pp. 444–448

- ^ a b Wynn 1994, p. 448

- ^ Edwards 1997, p. 58

- ^ Edwards 1997, p. 146

- ^ Stoddart 2014, p. 130.

References[]

- Bell, Christopher M. (2000). The Royal Navy, Seapower and Strategy between the Wars. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3978-1. OCLC 45224321.

- Bell, Christopher M. (June 2001). "The Singapore Strategy and the Deterrence of Japan: Winston Churchill, the Admiralty and the Dispatch of Force Z". The English Historical Review. Oxford University Press. 116 (467): 604–634. doi:10.1093/ehr/116.467.604. ISSN 0013-8266. JSTOR 579812.

- Brebner, J. Bartlet (March 1935). "Canada, The Anglo-Japanese Alliance and the Washington Conference". Political Science Quarterly. The Academy of Political Science. 50 (1): 45–58. doi:10.2307/2143412. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 2143412.

- Callahan, Raymond (April 1974). "The Illusion of Security: Singapore 1919–42". Journal of Contemporary History. Sage Publications, Ltd. 9 (2): 69–92. doi:10.1177/002200947400900203. ISSN 0022-0094. JSTOR 260047. S2CID 154024868.

- Cate, James Lea (1953). "The Twentieth Air Force and Matterhorn". In Craven, Wesley Frank; Cate, James Lea (eds.). Volume Five. The Pacific: Matterhorn to Nagasaki June 1944 to August 1945. The Army Air Forces in World War II. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press. OCLC 9828710. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- Churchill, Winston (1950). The Hinge of Fate. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-41058-4. OCLC 396148. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- Day, David (1988). The Great Betrayal: Britain, Australia and the Onset of the Pacific War, 1939–42. New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-02685-X. OCLC 18948548.

- Dennis, Peter (2010). "Australia and the Singapore Strategy". In Farrell, Brian P.; Hunter, Sandy (eds.). A Great Betrayal?: The Fall of Singapore Revisited. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. pp. 20–31. ISBN 978-981-4276-26-9. OCLC 462535579. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- Edwards, Peter (1997). A Nation at War: Australian Politics, Society and Diplomacy During the Vietnam War 1965–1975. Allen and Unwin. ISBN 1-86448-282-6.

- Farrell, Brian P. (2010). "Introduction". In Farrell, Brian P.; Hunter, Sandy (eds.). A Great Betrayal?: The Fall of Singapore Revisited. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. pp. vi–xiii. ISBN 978-981-4276-26-9. OCLC 462535579.

- Ferris, John R. (2010). "Student and Master: The United Kingdom, Japan, Airpower and the Fall of Singapore". In Farrell, Brian P.; Hunter, Sandy (eds.). A Great Betrayal?: The Fall of Singapore Revisited. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. pp. 74–97. ISBN 978-981-4276-26-9. OCLC 462535579.

- Field, Andrew (2004). Royal Navy Strategy in the Far East 1919–1939: Preparing for the War against Japan. Cass Series – Naval Policy and History. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 0-7146-5321-7. ISSN 1366-9478. OCLC 52688002.

- Gill, G. Hermon (1957). Royal Australian Navy 1939–1942. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. ISBN 0-00-217479-0. OCLC 848228.

- Gillison, Douglas (1962). Royal Australian Air Force 1939–1942. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 2000369.

- Hack, Ken; Blackburn, Kevin (2003). Did Singapore Have to Fall? Churchill and the Impregnable Fortress. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-30803-8. OCLC 310390398.

- Jones, Matthew (June 2003). "Up the Garden Path? Britain's Nuclear History in the Far East, 1954–1962". The International History Review. Routledge. 25 (2): 306–333. doi:10.1080/07075332.2003.9640998. ISSN 0707-5332. S2CID 154325126.

- Kennedy, Greg (2010). "Symbol of Imperial Defence". In Farrell, Brian P.; Hunter, Sandy (eds.). A Great Betrayal?: The Fall of Singapore Revisited. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. ISBN 978-981-4276-26-9. OCLC 462535579.

- Long, Gavin (1952). To Benghazi. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 18400892.

- McGibbon, Ian C. (1981). Blue-Water Rationale: The Naval Defence of New Zealand, 1914–1942. Wellington: Government Printer. ISBN 0-477-01072-5. OCLC 8494032.

- McIntyre, W. David (1979). The Rise and Fall of the Singapore Naval Base, 1919–1942. Cambridge Commonwealth Series. London: MacMillan Press. ISBN 0-333-24867-8. OCLC 5860782.

- Millett, Alan R. (1996). "Assault from the Sea-The Development Of Amphibious Warfare between the Wars : the American, British and Japanese Experiences". In Murray, Williamson; Millett, Alan R (eds.). Military Innovation in the Interwar Period. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 50–95. ISBN 0-521-55241-9. OCLC 33334760.

- Murfett, Malcolm M. (2010). "An Enduring Theme: The Singapore Strategy". In Farrell, Brian P.; Hunter, Sandy (eds.). A Great Betrayal?: The Fall of Singapore Revisited. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions. ISBN 978-981-4276-26-9. OCLC 462535579.

- Paterson, Rab (2008). "The Fall of Fortress Singapore: Churchill's Role and the Conflicting Interpretations" (PDF). Sophia International Review. Sophia University. 30. ISSN 0288-4607. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

- Roskill, S. W. (1954). The War at Sea: Volume I: the Defensive. History of the Second World War. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. OCLC 66711112.

- Stoddart, Kristan (2014). The Sword and the Shield : Britain, America, NATO, and Nuclear Weapons, 1970–1976. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-30093-4. OCLC 870285634.

- Till, Geoffrey (1996). "Adopting the Carrier Aircraft : the British, American and Japanese Case Studies". In Murray, Williamson; Millett, Alan R (eds.). Military Innovation in the Interwar Period. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 191–226. ISBN 0-521-55241-9. OCLC 33334760.

- Tate, Merze; Foy, Fidele (December 1959). "More Light on the Abrogation of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance". Political Science Quarterly. The Academy of Political Science. 74 (4): 532–554. doi:10.2307/2146422. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 2146422.

- Wigmore, Lionel (1957). The Japanese Thrust. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 3134219.

- Wynn, Humphrey (1994). RAF Nuclear Deterrent Forces. London: The Stationery Office. ISBN 0-11-772833-0. OCLC 31612798.

- Military of Singapore under British rule

- Military strategy

- British defence policymaking

- Military plans

- Military history of the Pacific Ocean

- Military history of the British Empire

- Interwar period

- British Malaya in World War II

- Military history of Malaya during World War II

- Military history of Singapore during World War II

- Military history of the British Empire and Commonwealth in World War II