Australian House of Representatives

House of Representatives | |

|---|---|

| 46th Parliament | |

| |

| Type | |

| Type | of the Parliament of Australia |

| Leadership | |

Speaker | Tony Smith, Liberal since 10 August 2015 |

Leader of the House | Peter Dutton, Liberal since 30 March 2021 |

Tony Burke, Labor since 18 October 2013 | |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 151 |

| |

Political groups | Government (76) Coalition |

| Elections | |

Voting system | Instant-runoff voting |

Last election | 18 May 2019 |

Next election | By 3 September 2022 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| House of Representatives Chamber Parliament House Canberra, Australian Capital Territory Australia | |

| Website | |

| House of Representatives | |

Politics of Australia |

|---|

|

|

Coordinates: 35°18′31″S 149°07′30″E / 35.308582°S 149.125107°E

The House of Representatives is the lower house of the bicameral Parliament of Australia, the upper house being the Senate. Its composition and powers are established in Chapter I of the Constitution of Australia.

The term of members of the House of Representatives is a maximum of three years from the date of the first sitting of the House, but on only one occasion since Federation has the maximum term been reached. The House is almost always dissolved earlier, usually alone but sometimes in a double dissolution of both Houses. Elections for members of the House of Representatives are often held in conjunction with those for the Senate. A member of the House may be referred to as a "Member of Parliament" ("MP" or "Member"), while a member of the Senate is usually referred to as a "Senator". The government of the day and by extension the Prime Minister must achieve and maintain the confidence of this House in order to gain and remain in power.

The House of Representatives currently consists of 151 members, elected by and representing single member districts known as electoral divisions (commonly referred to as "electorates" or "seats"). The number of members is not fixed but can vary with boundary changes resulting from electoral redistributions, which are required on a regular basis. The most recent overall increase in the size of the House, which came into effect at the 1984 election, increased the number of members from 125 to 148. It reduced to 147 at the 1993 election, returned to 148 at the 1996 election, increased to 150 at the 2001 election, and stands at 151 as of the 2019 Australian federal election.[1]

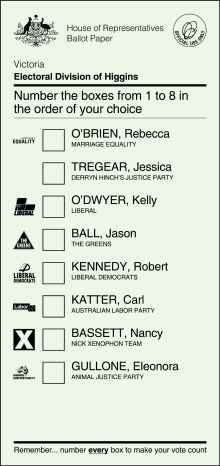

Each division elects one member using full-preferential instant-runoff voting. This was put in place after the 1918 Swan by-election, which Labor unexpectedly won with the largest primary vote and the help of vote splitting in the conservative parties. The Nationalist government of the time changed the lower house voting system from first-past-the-post to full-preferential voting, effective from the 1919 general election.

Origins and role[]

The Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act (Imp.) of 1900 established the House of Representatives as part of the new system of dominion government in newly federated Australia. The House is presided over by the Speaker. Members of the House are elected from single member electorates (geographic districts, commonly referred to as "seats" but officially known as "Divisions of the Australian House of Representatives"). One vote, one value legislation requires all electorates to have approximately the same number of voters with a maximum 10% variation. However, the baseline quota for the number of voters in an electorate is determined by the number of voters in the state in which that electorate is found. Consequently, the electorates of the smallest states and territories have more variation in the number of voters in their electorates. Meanwhile, all the states except Tasmania have electorates approximately within the same 10% tolerance, with most electorates holding 85,000 to 105,000 voters. Federal electorates have their boundaries redrawn or redistributed whenever a state or territory has its number of seats adjusted, if electorates are not generally matched by population size or if seven years have passed since the most recent redistribution.[2] Voting is by the 'preferential system', also known as instant-runoff voting. A full allocation of preferences is required for a vote to be considered formal. This allows for a calculation of the two-party-preferred vote.

Under Section 24 of the Constitution, each state is entitled to members based on a population quota determined from the "latest statistics of the Commonwealth."[3] These statistics arise from the census conducted under the auspices of section 51(xi).[4] Until its repeal by the 1967 referendum, section 127 prohibited the inclusion of Aboriginal people in section 24 determinations as including the Indigenous peoples could alter the distribution of seats between the states to the benefit of states with larger Aboriginal populations.[5] Section 127, along with section 25 (allowing for race-based disqualification of voters by states)[3] and the race power,[6] have been described as racism built into Australia's constitutional DNA,[7] and modifications to prevent lawful race-based discrimination have been proposed.[8]

The parliamentary entitlement of a state or territory is established by the Electoral Commissioner dividing the number of the people of the Commonwealth by twice the number of Senators. This is known as the "Nexus Provision". The reasons for this are twofold, to maintain a constant influence for the smaller states and to maintain a constant balance of the two Houses in case of a joint sitting after a double dissolution. The population of each state and territory is then divided by this quota to determine the number of members to which each state and territory is entitled. Under the Australian Constitution all original states are guaranteed at least five members. The Federal Parliament itself has decided that the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory should have at least one member each.

According to the Constitution, the powers of both Houses are nearly equal, with the consent of both Houses needed to pass legislation. The difference mostly relates to taxation legislation. In practice, by convention, the person who can control a majority of votes in the lower house is invited by the Governor-General to form the Government. In practice that means that the leader of the party (or coalition of parties) with a majority of members in the House becomes the Prime Minister, who then can nominate other elected members of the government party in both the House and the Senate to become ministers responsible for various portfolios and administer government departments. Bills appropriating money (supply bills) can only be introduced in the lower house and thus only the party with a majority in the lower house can govern. In the current Australian party system, this ensures that virtually all contentious votes are along party lines, and the Government usually has a majority in those votes.

The Opposition party's main role in the House is to present arguments against the Government's policies and legislation where appropriate, and attempt to hold the Government accountable as much as possible by asking questions of importance during Question Time and during debates on legislation. By contrast, the only period in recent times during which the government of the day has had a majority in the Senate was from July 2005 (following the 2004 election) to December 2007 (following the Coalition's defeat at the federal election that year). Hence, votes in the Senate are usually more meaningful. The House's well-established committee system is not always as prominent as the Senate committee system because of the frequent lack of Senate majority.

In a reflection of the United Kingdom House of Commons, the predominant colour of the furnishings in the House of Representatives is green. However, the colour was tinted slightly in the new Parliament House (opened 1988) to suggest the colour of eucalyptus trees. Also, unlike the House of Commons, the seating arrangement of the crossbench is curved, similar to the curved seating arrangement of the United States House of Representatives. This suggests a more collaborative, and less oppositional, system than in the United Kingdom parliament (where all members of parliament are seated facing the opposite side).[citation needed]

Australian parliaments are notoriously rowdy, with MPs often trading colourful insults. As a result, the Speaker often has to use the disciplinary powers granted to him or her under Standing Orders.[9]

Since 2015, Australian Federal Police officers armed with assault rifles have been present in both chambers of the Federal Parliament.[10]

Electoral system[]

From the beginning of Federation until 1918, first-past-the-post voting was used in order to elect members of the House of Representatives but since the 1918 Swan by-election which Labor unexpectedly won with the largest primary vote due to vote splitting amongst the conservative parties, the Nationalist Party government, a predecessor of the modern-day Liberal Party of Australia, changed the lower house voting system to Instant-runoff voting, which in Australia is known as full preferential voting, as of the subsequent 1919 election.[11] This system has remained in place ever since, allowing the Coalition parties to safely contest the same seats.[12] Full-preference preferential voting re-elected the Hawke government at the 1990 election, the first time in federal history that Labor had obtained a net benefit from preferential voting.[13]

From 1949 onwards, the vast majority of electorates, nearly 90%, are won by the candidate leading on first preferences, giving the same result as if the same votes had been counted using first-past-the-post voting. The highest proportion of seats (up to 2010) won by the candidate not leading on first preferences was the 1972 federal election, with 14 of 125 seats not won by the plurality candidate.[14]

Allocation process for the House of Representatives[]

The main elements of the operation of preferential voting for single-member House of Representatives divisions are as follows:[15][16]

- Voters are required to place the number "1" against their first choice of candidate, known as the "first preference" or "primary vote".

- Voters are then required to place the numbers "2", "3", etc., against all of the other candidates listed on the ballot paper, in order of preference. (Every candidate must be numbered, otherwise the vote becomes "informal" (spoiled) and does not count.[17])

- Prior to counting, each ballot paper is examined to ensure that it is validly filled in (and not invalidated on other grounds).

- The number "1" or first preference votes are counted first. If no candidate secures an absolute majority (more than half) of first preference votes, then the candidate with the fewest votes is excluded from the count.

- The votes for the eliminated candidate (i.e. from the ballots that placed the eliminated candidate first) are re-allocated to the remaining candidates according to the number "2" or "second preference" votes.

- If no candidate has yet secured an absolute majority of the vote, then the next candidate with the fewest primary votes is eliminated. This preference allocation is repeated until there is a candidate with an absolute majority. Where a second (or subsequent) preference is expressed for a candidate who has already been eliminated, the voter's third or subsequent preferences are used.

Following the full allocation of preferences, it is possible to derive a two-party-preferred figure, where the votes have been allocated between the two main candidates in the election. In Australia, this is usually between the candidates from the Coalition parties and the Australian Labor Party.

Relationship with the Government[]

Under the Constitution, the Governor-General has the power to appoint and dismiss "Ministers of State" who administer government departments. In practice, the Governor-General chooses ministers in accordance with the traditions of the Westminster system that the Government be drawn from the party or coalition of parties that has a majority in the House of Representatives, with the leader of the largest party becoming Prime Minister.

These ministers then meet in a council known as Cabinet. Cabinet meetings are strictly private and occur once a week where vital issues are discussed and policy formulated. The Constitution does not recognise the Cabinet as a legal entity; it exists solely by convention. Its decisions do not in and of themselves have legal force. However, it serves as the practical expression of the Federal Executive Council, which is Australia's highest formal governmental body.[18] In practice, the Federal Executive Council meets solely to endorse and give legal force to decisions already made by the Cabinet. All members of the Cabinet are members of the Executive Council. While the Governor-General is nominal presiding officer, he almost never attends Executive Council meetings. A senior member of the Cabinet holds the office of Vice-President of the Executive Council and acts as presiding officer of the Executive Council in the absence of the Governor-General. The Federal Executive Council is the Australian equivalent of the Executive Councils and privy councils in other Commonwealth realms such as the Queen's Privy Council for Canada and the Privy Council of the United Kingdom.[19]

A minister is not required to be a Senator or Member of the House of Representatives at the time of their appointment, but their office is forfeited if they do not become a member of either house within three months of their appointment. This provision was included in the Constitution (section 64) to enable the inaugural Ministry, led by Edmund Barton, to be appointed on 1 January 1901, even though the first federal elections were not scheduled to be held until 29 and 30 March.[20]

After the 1949 election, Bill Spooner was appointed a Minister in the Fourth Menzies Ministry on 19 December, however his term as a Senator did not begin until 22 February 1950.[21]

The provision was also used after the disappearance and presumed death of the Liberal Prime Minister Harold Holt in December 1967. The Liberal Party elected John Gorton, then a Senator, as its new leader, and he was sworn in as Prime Minister on 10 January 1968 (following an interim ministry led by John McEwen). On 1 February, Gorton resigned from the Senate to stand for the 24 February by-election in Holt's former House of Representatives electorate of Higgins due to the convention that the Prime Minister be a member of the lower house. For 22 days (2 to 23 February inclusive) he was Prime Minister while a member of neither house of parliament.[22]

On a number of occasions when Ministers have retired from their seats prior to an election, or stood but lost their own seats in the election, they have retained their Ministerial offices until the next government is sworn in.

Committees[]

In addition to the work of the main chamber, the House of Representatives also has a large number of committees which deal with matters referred to them by the main House. They provide the opportunity for all Members to ask questions of ministers and public officials as well as conduct inquiries, examine policy and legislation.[23] Once a particular inquiry is completed the members of the committee can then produce a report, to be tabled in Parliament, outlining what they have discovered as well as any recommendations that they have produced for the Government to consider.[24]

The ability of the Houses of Parliament to establish committees is referenced in Section 49 of the Constitution, which states that, "The powers, privileges, and immunities of the Senate and of the House of Representatives, and of the members and the committees of each House, shall be such as are declared by the Parliament, and until declared shall be those of the Commons House of Parliament of the United Kingdom, and of its members and committees, at the establishment of the Commonwealth."[25][24]

Parliamentary committees can be given a wide range of powers. One of the most significant powers is the ability to summon people to attend hearings in order to give evidence and submit documents. Anyone who attempts to hinder the work of a Parliamentary committee may be found to be in contempt of Parliament. There are a number of ways that witnesses can be found in contempt. These include refusing to appear before a committee when summoned, refusing to answer a question during a hearing or to produce a document, or later being found to have lied to or misled a committee. Anyone who attempts to influence a witness may also be found in contempt.[26] Other powers include, the ability to meet throughout Australia, to establish subcommittees and to take evidence in both public and private hearings.[24]

Proceedings of committees are considered to have the same legal standing as proceedings of Parliament, they are recorded by Hansard, except for private hearings, and also operate under Parliamentary privilege. Every participant, including committee members and witnesses giving evidence, are protected from being prosecuted under any civil or criminal action for anything they may say during a hearing. Written evidence and documents received by a committee are also protected.[26][24]

Types of committees include:[26]

Standing Committees, which are established on a permanent basis and are responsible for scrutinising bills and topics referred to them by the chamber; examining the government's budget and activities and for examining departmental annual reports and activities.

Select Committees, which are temporary committees, established in order to deal with particular issues.

Domestic Committees, which are responsible for administering aspects of the House's own affairs. These include the Selection Committee that determines how the House will deal with particular pieces of legislation and private members business and the Privileges Committee that deals with matters of Parliamentary Privilege.

Legislative Scrutiny Committees, which examine legislation and regulations to determine their impact on individual rights and accountability.

Joint Committees are also established to include both members of the House of Representatives and the Senate.

Federation Chamber[]

The Federation Chamber is a second debating chamber that considers relatively uncontroversial matters referred by the House. The Federation Chamber cannot, however, initiate or make a final decision on any parliamentary business, although it can perform all tasks in between.[27]

The Federation Chamber was created in 1994 as the Main Committee, to relieve some of the burden of the House: different matters can be processed in the House at large and in the Federation Chamber, as they sit simultaneously. It is designed to be less formal, with a quorum of only three members: the Deputy Speaker of the House, one government member, and one non-government member. Decisions must be unanimous: any divided decision sends the question back to the House at large.

The Federation Chamber was created through the House's Standing Orders:[28] it is thus a subordinate body of the House, and can only be in session while the House itself is in session. When a division vote in the House occurs, members in the Federation Chamber must return to the House to vote.

The Federation Chamber is housed in one of the House's committee rooms; the room is customised for this purpose and is laid out to resemble the House chamber.[29]

Due to the unique role of what was then called the Main Committee, proposals were made to rename the body to avoid confusion with other parliamentary committees, including "Second Chamber"[30] and "Federation Chamber".[31] The House of Representatives later adopted the latter proposal.[32]

The concept of a parallel body to expedite Parliamentary business, based on the Australian Federation Chamber, was mentioned in a 1998 British House of Commons report,[33] which led to the creation of that body's parallel chamber Westminster Hall.[34]

Current House of Representatives[]

The current Parliament is the 46th Australian Parliament. The most recent federal election was held on 18 May 2019 and the 46th Parliament first sat in July.

The outcome of the 2019 election saw the incumbent Liberal/National Coalition government re-elected for a third term with 77 seats in the 151-seat House of Representatives (an increase of 1 seat compared to the 2016 election), a two-seat majority government. The Shorten Labor opposition won 68 seats, a decrease of 1 seat. On the crossbench, the Australian Greens, the Centre Alliance, Katter's Australian Party, and independents Andrew Wilkie, Helen Haines and Zali Steggall won a seat each.[35]

House of Representatives primary, two-party and seat results[]

A two-party system has existed in the Australian House of Representatives since the two non-Labor parties merged in 1909. The 1910 election was the first to elect a majority government, with the Australian Labor Party concurrently winning the first Senate majority. Prior to 1909 a three-party system existed in the chamber. A two-party-preferred vote (2PP) has been calculated since the 1919 change from first-past-the-post to preferential voting and subsequent introduction of the Coalition. ALP = Australian Labor Party, L+NP = grouping of Liberal/National/LNP/CLP Coalition parties (and predecessors), Oth = other parties and independents.

| Election Year |

Labour | Free Trade | Protectionist | Independent | Other parties |

Total seats | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 1901 | 14 | 28 | 31 | 2 | 75 | ||||

| Election Year |

Labour | Free Trade | Protectionist | Independent | Other parties |

Total seats | ||||

| 2nd | 1903 | 23 | 25 | 26 | 1 | Revenue Tariff | 75 | |||

| Election Year |

Labour | Anti-Socialist | Protectionist | Independent | Other parties |

Total seats | ||||

| 3rd | 1906 | 26 | 26 | 21 | 1 | 1 | Western Australian | 75 | ||

| Primary vote | 2PP vote | Seats | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALP | L+NP | Oth. | ALP | L+NP | ALP | L+NP | Oth. | Total | |

| 13 April 1910 election | 50.0% | 45.1% | 4.9% | – | – | 42 | 31 | 2 | 75 |

| 31 May 1913 election | 48.5% | 48.9% | 2.6% | – | – | 37 | 38 | 0 | 75 |

| 5 September 1914 election | 50.9% | 47.2% | 1.9% | – | – | 42 | 32 | 1 | 75 |

| 5 May 1917 election | 43.9% | 54.2% | 1.9% | – | – | 22 | 53 | 0 | 75 |

| 13 December 1919 election | 42.5% | 54.3% | 3.2% | 45.9% | 54.1% | 25 | 38 | 2 | 75 |

| 16 December 1922 election | 42.3% | 47.8% | 9.9% | 48.8% | 51.2% | 29 | 40 | 6 | 75 |

| 14 November 1925 election | 45.0% | 53.2% | 1.8% | 46.2% | 53.8% | 23 | 50 | 2 | 75 |

| 17 November 1928 election | 44.6% | 49.6% | 5.8% | 48.4% | 51.6% | 31 | 42 | 2 | 75 |

| 12 October 1929 election | 48.8% | 44.2% | 7.0% | 56.7% | 43.3% | 46 | 24 | 5 | 75 |

| 19 December 1931 election | 27.1% | 48.4% | 24.5% | 41.5% | 58.5% | 14 | 50 | 11 | 75 |

| 15 September 1934 election | 26.8% | 45.6% | 27.6% | 46.5% | 53.5% | 18 | 42 | 14 | 74 |

| 23 October 1937 election | 43.2% | 49.3% | 7.5% | 49.4% | 50.6% | 29 | 43 | 2 | 74 |

| 21 September 1940 election | 40.2% | 43.9% | 15.9% | 50.3% | 49.7% | 32 | 36 | 6 | 74 |

| 21 August 1943 election | 49.9% | 23.0% | 27.1% | 58.2% | 41.8% | 49 | 19 | 6 | 74 |

| 28 September 1946 election | 49.7% | 39.3% | 11.0% | 54.1% | 45.9% | 43 | 26 | 5 | 74 |

| 10 December 1949 election | 46.0% | 50.3% | 3.7% | 49.0% | 51.0% | 47 | 74 | 0 | 121 |

| 28 April 1951 election | 47.6% | 50.3% | 2.1% | 49.3% | 50.7% | 52 | 69 | 0 | 121 |

| 29 May 1954 election | 50.0% | 46.8% | 3.2% | 50.7% | 49.3% | 57 | 64 | 0 | 121 |

| 10 December 1955 election | 44.6% | 47.6% | 7.8% | 45.8% | 54.2% | 47 | 75 | 0 | 122 |

| 22 November 1958 election | 42.8% | 46.6% | 10.6% | 45.9% | 54.1% | 45 | 77 | 0 | 122 |

| 9 December 1961 election | 47.9% | 42.1% | 10.0% | 50.5% | 49.5% | 60 | 62 | 0 | 122 |

| 30 November 1963 election | 45.5% | 46.0% | 8.5% | 47.4% | 52.6% | 50 | 72 | 0 | 122 |

| 26 November 1966 election | 40.0% | 50.0% | 10.0% | 43.1% | 56.9% | 41 | 82 | 1 | 124 |

| 25 October 1969 election | 47.0% | 43.3% | 9.7% | 50.2% | 49.8% | 59 | 66 | 0 | 125 |

| 2 December 1972 election | 49.6% | 41.5% | 8.9% | 52.7% | 47.3% | 67 | 58 | 0 | 125 |

| 18 May 1974 election | 49.3% | 44.9% | 5.8% | 51.7% | 48.3% | 66 | 61 | 0 | 127 |

| 13 December 1975 election | 42.8% | 53.1% | 4.1% | 44.3% | 55.7% | 36 | 91 | 0 | 127 |

| 10 December 1977 election | 39.7% | 48.1% | 12.2% | 45.4% | 54.6% | 38 | 86 | 0 | 124 |

| 18 October 1980 election | 45.2% | 46.3% | 8.5% | 49.6% | 50.4% | 51 | 74 | 0 | 125 |

| 5 March 1983 election | 49.5% | 43.6% | 6.9% | 53.2% | 46.8% | 75 | 50 | 0 | 125 |

| 1 December 1984 election | 47.6% | 45.0% | 7.4% | 51.8% | 48.2% | 82 | 66 | 0 | 148 |

| 11 July 1987 election | 45.8% | 46.1% | 8.1% | 50.8% | 49.2% | 86 | 62 | 0 | 148 |

| 24 March 1990 election | 39.4% | 43.5% | 17.1% | 49.9% | 50.1% | 78 | 69 | 1 | 148 |

| 13 March 1993 election | 44.9% | 44.3% | 10.7% | 51.4% | 48.6% | 80 | 65 | 2 | 147 |

| 2 March 1996 election | 38.7% | 47.3% | 14.0% | 46.4% | 53.6% | 49 | 94 | 5 | 148 |

| 3 October 1998 election | 40.1% | 39.5% | 20.4% | 51.0% | 49.0% | 67 | 80 | 1 | 148 |

| 10 November 2001 election | 37.8% | 43.0% | 19.2% | 49.0% | 51.0% | 65 | 82 | 3 | 150 |

| 9 October 2004 election | 37.6% | 46.7% | 15.7% | 47.3% | 52.7% | 60 | 87 | 3 | 150 |

| 24 November 2007 election | 43.4% | 42.1% | 14.5% | 52.7% | 47.3% | 83 | 65 | 2 | 150 |

| 21 August 2010 election | 38.0% | 43.3% | 18.7% | 50.1% | 49.9% | 72 | 72 | 6 | 150 |

| 7 September 2013 election | 33.4% | 45.6% | 21.0% | 46.5% | 53.5% | 55 | 90 | 5 | 150 |

| 2 July 2016 election | 34.7% | 42.0% | 23.3% | 49.6% | 50.4% | 69 | 76 | 5 | 150 |

| 18 May 2019 election | 33.3% | 41.4% | 25.2% | 48.5% | 51.5% | 68 | 77 | 6 | 151 |

See also[]

- 2019 Australian federal election

- Australian House of Representatives committees

- Canberra Press Gallery

- Chronology of Australian federal parliaments

- Clerk of the Australian House of Representatives

- Father of the Australian House of Representatives

- List of Australian federal by-elections

- Members of the Australian House of Representatives

- Members of the Australian Parliament who have served for at least 30 years

- Members of the Australian Parliament who have represented more than one state or territory

- Speaker of the Australian House of Representatives

- Women in the Australian House of Representatives

- Browne–Fitzpatrick privilege case, 1955

Notes[]

References[]

- ^ Determination of membership entitlement to the House of Representatives

- ^ Barber, Stephen (25 August 2016). "Electoral Redistributions during the 45th Parliament". Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 (UK), page 6". Museum of Australian Democracy. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ "Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 (UK), page 10". Museum of Australian Democracy. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ Korff, Jens (8 October 2014). "Australian 1967 Referendum". creativespirits.info. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- ^ "Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 (UK), page 11". Museum of Australian Democracy. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ^ Williams, George (2012). "Removing racism from Australia's constitutional DNA". Alternative Law Journal. 37 (3): 151–155. doi:10.1177/1037969X1203700302. S2CID 145522774. SSRN 2144763.

- ^ Expert Panel on Recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in the Constitution (January 2012). Recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in the Constitution. Commonwealth of Australia. ISBN 978-1-921975-29-5.

- ^ Madigan, Michael (27 February 2009). "Barking, biting dog House". Winnipeg Free Press. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- ^ "Armed guards now stationed to protect Australian MPs and senators in both chambers of Federal Parliament". The Sydney Morning Herald. 9 February 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ "A Short History of Federal Election Reform in Australia". Australian electoral history. Australian Electoral Commission. 8 June 2007. Retrieved 1 July 2007.

- ^ Green, Antony (2004). "History of Preferential Voting in Australia". Antony Green Election Guide: Federal Election 2004. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 1 July 2007.

- ^ "The Origin of Senate Group Ticket Voting, and it didn't come from the Major Parties". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- ^ Green, Antony (11 May 2010). "Preferential Voting in Australia". www.abc.net.au. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ "Preferential Voting". Australianpolitics.com. Archived from the original on 14 May 2010. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ^ "How the House of Representatives votes are counted". Australian Electoral Commission. 13 February 2013. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ "How does Australia's voting system work?". The Guardian. 14 August 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- ^ "Federal Executive Council Handbook". Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Archived from the original on 4 March 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ Hamer, David (2004). The executive government (PDF). Department of the Senate (Australia). p. 113. ISBN 0-642-71433-9.

- ^ Rutledge, Martha. "Sir Edmund (1849–1920)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Australian National University. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ^ Starr, Graeme (2000). "Spooner, Sir William Henry (1897–1966)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne University Press. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 7 January 2008 – via National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- ^ "John Gorton Prime Minister from 10 January 1968 to 10 March 1971". National Museum of Australia. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ "Committees". aph.gov.au. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Odgers' Australian Senate Practice Fourteenth Edition Chapter 16 - Committees". 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ Constitution of Australia, section 49.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Infosheet 4 - Committees". aph.gov.au. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

- ^ "The Structure Of The Australian House Of Representatives Over Its First One Hundred Years: The Impact Of Globalisation," Ian Harris

- ^ Standing and Sessional Orders Archived 3 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine, House of Representatives

- ^ Main Committee Fact Sheet Archived 31 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Parliamentary Education Office

- ^ The Second Chamber: Enhancing the Main Committee, House of Representatives

- ^ Renaming the Main Committee, House of Representatives

- ^ [House of Representatives Vote and Proceedings], 8 February 2012, Item 8.

- ^ "Select Committee on Modernisation of the House of Commons First Report". House of Commons of the United Kingdom. 7 December 1998. Retrieved 20 June 2007.

- ^ House of Commons Standard Note—Modernization: Westminster Hall, SN/PC/3939. Updated 6 March 2006. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- ^ "Federal Election 2019 Results". ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). Retrieved 21 June 2019.

Further reading[]

- Souter, Gavin (1988). Acts of Parliament: A narrative history of the Senate and House of Representatives, Commonwealth of Australia. Carlton: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0-522-84367-0.

- Quick, John & Garran, Robert (1901). The Annotated Constitution of the Australian Commonwealth. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. ISBN 0-9596568-0-4. In Internet Archive

- B.C. Wright, House of Representatives Practice (6th Ed.), A detailed reference work on all aspects of the House of Representatives' powers, procedures and practices.

External links[]

| Library resources about Australian House of Representatives |

- House of Representatives – Official website.

- Australian Parliament – live broadcasting

- 1901 establishments in Australia

- National lower houses

- Politics of Australia

- Westminster system

- Parliament of Australia

- Australian House of Representatives