Azerbaijanis in Armenia

View of Mount Ararat from a nearby Tatar (Azerbaijani) village (1838) | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 29[1] (2001) | |

| Languages | |

| Azerbaijani | |

| Religion | |

| Islam (mostly Shia) |

Azerbaijanis in Armenia (Azerbaijani: Ermənistan azərbaycanlıları or Qərbi azərbaycanlılar, lit. 'Western Azerbaijanis') were once the largest ethnic minority in the country, but have been virtually non-existent since 1988–1991 when most either fled the country or were pushed out as a result of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War and the ongoing conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan. UNHCR estimates the current population of Azerbaijanis in Armenia to be somewhere between 30 and a few hundred people,[2] with the majority of them living in rural areas and being members of mixed couples (mostly mixed marriages), as well as elderly or sick. Most of them are reported to have changed their names to maintain low profiles to avoid discrimination.[3][4]

History

Pre-Russian rule

Upon Seljuk conquests in the eleventh century, the mass of the Oghuz Turkic tribes crossed the Amu Darya towards the west left the Iranian plateau, which remained Persian, and established themselves further west, in Armenia, the Caucasus, and Anatolia. Here they divided into the Ottomans, who were Sunni and created settlements, and the Turcomans, who were nomads and in part Shiite (or, rather, Alevi), gradually becoming sedentary and assimilating with the local population.

Until the mid-fourteenth century, Armenians had constituted a majority in Eastern Armenia.[5] At the close of the fourteenth century, after Timur's campaigns of the extermination of the local population, Islam had become the dominant faith, and Armenians became a minority in Eastern Armenia.[5] After centuries of constant warfare on the Armenian Plateau, many Armenians chose to emigrate and settle elsewhere. Following Shah Abbas I's massive relocation of Armenians and Muslims in 1604–05,[6] their numbers dwindled even further.

Some 80% of the population of Iranian Armenia were Muslims (Persians, Turkics, and Kurds) whereas Christian Armenians constituted a minority of about 20%.[7] As a result of the Treaty of Gulistan (1813) and the Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828), Iran was forced to cede Iranian Armenia (which also constituted the present-day Republic of Armenia), to the Russians.[8][9]

Russian rule

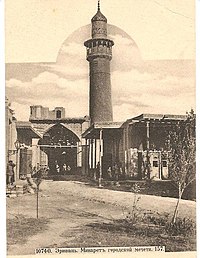

After the Russian administration took hold of Iranian Armenia, the ethnic make-up shifted, and thus for the first time in more than four centuries, ethnic Armenians started to form a majority once again in one part of historic Armenia.[10] The new Russian administration encouraged the settling of ethnic Armenians from Iran proper and Ottoman Turkey. As a result, by 1832, the number of ethnic Armenians had matched that of the Muslims.[7] Anyhow, it would be only after the Crimean War and the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, which brought another influx of Turkish Armenians, that ethnic Armenians once again established a solid majority in Eastern Armenia.[11] Nevertheless, the city of Erivan (present-day Yerevan) remained having a Muslim majority up to the twentieth century.[11] According to the traveler H. F. B. Lynch, the city was about 50% Armenian and 50% Muslim (Azerbaijanis and Persians) in the early 1890s.[12]

According to the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary, by the beginning of the twentieth century a significant population of Azerbaijanis still lived in Russian Armenia. They numbered about 300,000 persons or 37.5% in Russia's Erivan Governorate (roughly corresponding to most of present-day central Armenia, the Iğdır Province of Turkey, and Azerbaijan's Nakhchivan exclave).[13]

Most lived in rural areas and were engaged in farming and carpet-weaving. They formed the majority in four of the governorate's seven districts, including the city of Erivan itself, where they constituted 49% of the population (compared to 48% constituted by Armenians).[14] Azerbaijanis also constituted a majority in what later became the regions of Sisian, Kafan and Meghri in the Armenian SSR (present-day Syunik Province, Armenia, at the time part of the Elisabethpol Governorate).[15] Traditionally, Azerbaijanis in Armenia were almost entirely Shia Muslim, with the exception of the Talin region, as well as small pockets in Shorayal and around Vedi where they mainly adhered to Sunni Islam.[16] Traveller Luigi Villari reported in 1905 that in Erivan the Azerbaijanis (to whom he referred as Tartars) were generally wealthier than the Armenians, and owned nearly all of the land.[17]

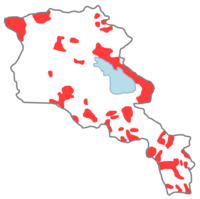

Distribution of Azerbaijanis in modern borders of Armenia, 1886–1890.

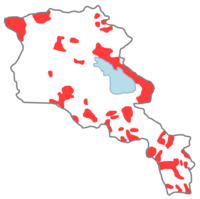

Distribution of Azerbaijanis in the Armenian SSR, 1926.

Distribution of Azerbaijanis in the Armenian SSR, 1962.

For Azerbaijanis of Armenia, the twentieth century was the period of marginalization, discrimination, mass and often forcible migrations[18] resulting in significant changes in the country's ethnic composition, even though they had managed to stay its largest ethnic minority until the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. In 1905–1907 Erivan Governorate became an arena of clashes between Armenians and Azerbaijanis believed to have been instigated by the Russian government in order to draw public attention away from the Russian Revolution of 1905.[19]

First Republic of Armenia

Tensions rose again after both Armenia and Azerbaijan became briefly independent from the Russian Empire in 1918. Both quarrelled over where their common borders lay.[20] Warfare coupled with the influx of Armenian refugees resulted in widespread massacres of Muslims in Armenia[21][22][23][24] causing virtually all of them to flee to Azerbaijan.[18] Andranik Ozanian and Rouben Ter Minassian were particularly prominent in the destruction of Muslim settlements and in the planned ethnic homogenisation of regions with once mixed population through populating them with Armenian refugees from Turkey.[25] Ter Minassian, displeased with the fact that Azerbaijanis in Armenia lived on fertile lands, waged at least three campaigns aimed at cleansing Azerbaijanis from 20 villages outside Erivan, as well as in the south of the country. According to French historian (and Ter Minassian's daughter-in-law) Anahide Ter Minassian, to achieve his goals, he used intimidation and negotiations, but above all, "fire and steel" and "the most violent methods to 'encourage' Muslims in Armenia" to leave.[26]

Though Azerbaijanis were represented by three delegates in an 80-seat Armenian parliament (much more modestly than Armenians in the Azerbaijani parliament), they were universally targeted as "Turkish fifth columnists".[26] In his June 1919 report, Anastas Mikoyan stated that "the organised extermination of the Muslim population in Armenia threatened to result in Azerbaijan declaring a war [against Armenia] any minute".[27] According to British reports, some 250 Muslim villages had been burnt in the eastern Caucasus as a result of a killing spree initiated by Armenian units led by Andranik Ozanian.[28]

Soviet Armenia

Relatively few of the evicted Azerbaijanis returned, as according to the 1926 All-Soviet population census there were only 84,705 Azerbaijanis living in Armenia, comprising 9.6% of the population.[29] By 1939 their numbers had increased to 131,896.[30]

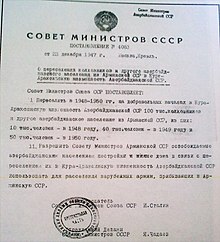

In 1947, Grigory Arutinov, then First Secretary of the Communist Party of Armenia, managed to persuade the Council of Ministers of the USSR to issue a decree entitled Planned measures for the resettlement of collective farm workers and other Azerbaijanis from the Armenian SSR to the Kura-Arax lowlands of the Azerbaijani SSR.[31] According to the decree, between 1948 and 1951, the Azeri community in Armenia became partly subject to a "voluntary resettlement" (called by some sources a deportation[32][33][34]) to central Azerbaijan[35] to make way for Armenian immigrants from the Armenian diaspora. In those four years some 100,000 Azerbaijanis were deported from Armenia.[29] This reduced the number of those in Armenia down to 107,748 in 1959.[36] By 1979, Azerbaijanis numbered 160,841 and constituted 5.3% of Armenia's population.[37] The Azeri population of Yerevan, that once formed the majority, dropped to 0.7% by 1959 and further to 0.1% by 1989.[33]

Soviet education policy ensured the availability of schools with Azeri as the language of instruction in Armenia.[38] In 1979, among the 160,841 Azers living in Armenia, Armenian was spoken as a second language by 16,164 (10%) and Russian by 15,879 (9.9%)[39] (compared to Armenians in Azerbaijan, of whom 8% knew Azeri and 43% knew Russian).[40]

In 1934–1944, prior to rising to fame in Azerbaijan, prominent singer Rashid Behbudov was a soloist of the Yerevan Philharmonic and of the Armenian State Jazz Orchestra. Around the same time, he performed at the Armenian National Academic Theater of Opera and Ballet. Theatre and film critic Sabir Rzayev, an ethnic Azeri native of Yerevan, was the founder of Armenian film studies and the author of the first and only film-related monograph in Soviet Armenia.[41]

Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

| Part of a series on |

| Azerbaijanis |

|---|

| Culture |

| Traditional areas of settlement |

| Diaspora |

| Religion |

|

| Language |

|

| Persecution |

|

|

When the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict broke out, as the order of the Soviet Union was falling apart, Armenia had a large population of Azeri minorities.[42] Civil unrest in Nagorno-Karabakh in 1987 led to harassment of Azerbaijanis, some of whom were forced to leave Armenia.[43] What started off as peaceful demonstrations in support of the Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians, in the absence of a favourable solution, soon turned into a nationalist movement, manifesting in violence in Azerbaijan, Armenian, and Karabakh against the minority population.[44]

On 25 January 1988 the first wave of Azeri refugees from Armenia settled in the city of Sumgait.[43][45] On 23 March, the presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union – that is the highest institution in the Union – rejected the demands of the Nagorno-Karabakh Council of People's Deputies to join Armenia without any possibility of appeal. Troops were deployed in Yerevan to prevent protests to the decision. In the following months, Azerbaijanis in Armenia were subject to further harassment and forced to flee. In the district of Ararat, four villages were burned on 25 March. On 11 May, intimidation by violence forced many Azerbaijanis to migrate in Azerbaijan from Ararat in large numbers.[46] On 7 June, Azerbaijanis were evicted from the town of Masis near the Armenian–Turkish border, and on the 20 June of the same month five more Azeri villages were cleansed in the Ararat region.[47] Another major wave occurred in November 1988[45] as Azerbaijanis were either expelled by the nationalists and local or state authorities,[44] or fled fearing for their lives.[3] Many died in the process, either due to isolated Armenian attacks or adverse conditions.[44] Due to violence that flared up[48] in November 1988, 25 Azerbaijanis were killed, according to Armenian sources (of those 20 during Gugark pogrom);[49] and 217 (including those who died of extreme weather conditions while fleeing), according to Azerbaijani sources.[50]

In 1988–91, the remaining Azerbaijanis were forced to flee primarily to Azerbaijan.[44][51][52] It is impossible to determine the exact population numbers for Azerbaijanis in Armenia at the time of the conflict's escalation since during the 1989 census, forced Azeri migration from Armenia was already in progress. UNHCR's estimate is 200,000 persons.[3]

Current situation

According to journalist Thomas de Waal, A few residents of Vardanants Street recall a small mosque being demolished in 1990.[53] Geographical names of Turkic origin were changed en masse into Armenian-sounding ones[54] (in addition to those continuously changed from the 1930s on[29]), a measure seen by some as a method to erase from popular memory the fact that Muslims had once formed a substantial portion of the local population.[55] According to Husik Ghulyan's study, in the period 2006-2018, more than 7700 Turkic geographic names that existed in the country have been changed and replaced by Armenian names.[56] Those Turkic names were mostly located in areas that previously were heavily populated by Azerbaijanis, namely in Gegharkunik, Kotayk and Vayots Dzor regions and some parts of Syunik and Ararat regions.[56]

In 2001, historian Suren Hobosyan of the Armenian Institute of Archeology and Ethnography estimated that there were 300 to 500 people of Azeri origin living in Armenia, mostly descendants of mixed marriages, with only 60 to 100 being of full Azeri ancestry. In an anonymous case study of 15 people of Azeri origin (13 of mixed Armenian–Azeri and 2 of full Azeri ancestry) carried out in 2001 by the International Organization for Migration with the help of the non-governmental Armenian Sociological Association in Yerevan, Meghri, Sotk and Avazan, 12 respondents said they concealed their Azeri roots from the public, and only 3 said they identified as Azeri. 13 out of 15 respondents reported being Christian and none reported being Muslim.[57]

Some Azerbaijanis continue to live in Armenia to this day. Official statistics suggest there are 29 Azerbaijanis in Armenia as of 2001.[58] Hranush Kharatyan, the then head of the Department on National Minorities and Religion Matters of Armenia, stated in February 2007:

Yes, ethnic Azerbaijanis are living in Armenia. I know many of them but I cannot give numbers. Armenia has signed a UN convention according to which the states take an obligation not to publish statistical data related to groups under threat or who consider themselves to be under threat if these groups are not numerous and might face problems. During the census, a number of people described their ethnicity as Azerbaijani. I know some Azerbaijanis who came here with their wives or husbands. Some prefer not to speak out about their ethnic affiliation; others take it more easily. We spoke with some known Azerbaijanis residing in Armenia but they have not manifested a will to form an ethnic community yet.[59]

Prominent Azerbaijanis from Armenia

- Ashig Alasgar, 19th-century Azeri poet and folk singer[60]

- Mirza Gadim Iravani, Azeri painter of the mid-19th century

- Mammad agha Shahtakhtinski, Azerbaijani linguist and Member of the State Duma

- Akbar agha Sheykhulislamov, Minister of Agriculture of Azerbaijan in 1918–1920

- Abbasgulu bey Shadlinski, Soviet Azerbaijani military leader

- Heydar Huseynov, Azerbaijani philosopher

- Aziz Aliyev, Soviet politician

- Said Rustamov, Azerbaijani composer and conductor

- , Azerbaijani philologist[citation needed]

- Mustafa Topchubashov, prominent Soviet surgeon and academician

- Ali Insanov, former Minister of Healthcare of Azerbaijan

- Huseyn Seyidzadeh, Azerbaijani film director

- , Azerbaijani poet[citation needed]

- , Azerbaijani film director[citation needed]

- Ahliman Amiraslanov, Azerbaijani physician

- , former Minister of Education of Azerbaijan

- Ismat Abbasov, Minister of Agriculture of Azerbaijan

- , former President of the National Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan[citation needed]

- Avaz Alakbarov, Azerbaijani economist, ex-Minister of Finance of Azerbaijan

- Khagani Mammadov, Azerbaijani football player

- Khalaf Khalafov, Deputy Minister of the Foreign Affairs Ministry

- Ramazan Abbasov, Azerbaijani football player

- Rovshan Huseynov, Azerbaijani boxer

- Shahin Mustafayev, Minister of Economic Development of Azerbaijan

- Ogtay Asadov, Speaker of the National Assembly of Azerbaijan

- Hidayat Orujov, Azerbaijani writer and ambassador to Kyrgyzstan

- Garib Mammadov, Chairman of State Land and Cartography Committee of Azerbaijan Republic.

- Zulfi Hajiyev, Deputy Prime Minister of Azerbaijan, Member of Azerbaijani Parliament

- Yusif Yusifov, a prominent Azerbaijani historian, orientalist, linguist, specialist on ancient literature.

- , head of the State Migration Service[citation needed]

See also

- Armenia–Azerbaijan relations

- Yeraz

- Western Azerbaijan

- Islam in Armenia

- Anti-Azerbaijani sentiment in Armenia

- Blue Mosque, Yerevan

- Demographics of Armenia

- Armenians in Azerbaijan

References

- ^ https://archive.168.am/articles/10810

- ^ Second Report Submitted by Armenia Pursuant to Article 25, Paragraph 1 of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities. Received on 24 November 2004

- ^ Jump up to: a b c International Protection Considerations Regarding Armenian Asylum-Seekers and Refugees Archived 2014-04-16 at the Wayback Machine. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Geneva: September 2003

- ^ Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – 2003: Armenia U.S. Department of State. Released 25 February 2004

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bournoutian 1980, pp. 11, 13–14.

- ^ Arakel of Tabriz. The Books of Histories; chapter 4. Quote: "[The Shah] deep inside understood that he would be unable to resist Sinan Pasha, i.e. the Sardar of Jalaloghlu, in a[n open] battle. Therefore he ordered to relocate the whole population of Armenia – Christians, Jews, and Muslims alike, to Persia, so that the Ottomans find the country depopulated."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bournoutian 1980, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Bournoutian 1980, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Mikaberidze 2015, p. 141.

- ^ Bournoutian 1980, p. 14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bournoutian 1980, p. 13.

- ^ Kettenhofen, Bournoutian & Hewsen 1998, pp. 542–551.

- ^ "Эриванская губерния". Archived from the original on 9 July 2006. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ "Эривань". Archived from the original on 25 February 2006. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ Eddie Arnavoudian. Why we should read... Archived 2018-09-29 at the Wayback Machine. Armenian News Network / Groong. June 12, 2006. Retrieved August 16, 2013.

- ^ A. Tsutsiyev (2004) (АТЛАС ЭТНОПОЛИТИЧЕСКОЙ ИСТОРИИ КАВКАЗА, Цуциев А.А, Москва: Издательство «Европа», 2007)

- ^ Fire and Sword in the Caucasus by Luigi Villari. London, T. F. Unwin, 1906: p. 267

- ^ Jump up to: a b Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War by Thomas de Waal ISBN 0-8147-1945-7

- ^ (in Russian) Memories of the Revolution in Transcaucasia by Boris Baykov

- ^ de Waal. Black Garden. p. 127-8.

- ^ Modern Hatreds: The Symbolic Politics of Ethnic War by Stuart J. Kaufman. Cornell University Press. 2001. p.58 ISBN 0-8014-8736-6

- ^ "Turkish-Armenian War of 1920". Archived from the original on 12 March 2007.

- ^ (in Russian) Ethnic Conflicts in the USSR: 1917–1991 Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. State Archives of the Russian Federation, fund 1318, list 1, folder 413, document 21

- ^ (in Russian) Garegin Njdeh and the KGB: Report of Interrogation of Ohannes Hakopovich Devedjian Archived October 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine August 28, 1947. Retrieved May 31, 2007

- ^ The Great Game of Genocide: Imperialism, Nationalism, and the Destruction by Donald Bloxham. Oxford University Press: 2005, pp.103–105

- ^ Jump up to: a b Thomas de Waal. Great Catastrophe: Armenians and Turks in the Shadow of Genocide. Oxford University Press, 2014; p. 122

- ^ Stanislav Tarasov. Joseph Orbeli's Mystery: Part 7. 7 July 2014.

- ^ Levene, Mark (2013). Devastation. Oxford University Press. pp. 217, 218. ISBN 9780191505546.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c The Alteration of Place Names and Construction of National Identity in Soviet Armenia Archived September 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine by Arseny Sarapov

- ^ (in Russian)All-Soviet Population Census of 1939 – Ethnic Composition in the Republics of the USSR: Armenian SSR. Demoscope.ru

- ^ A Failed Empire: The Soviet Union in the Cold War from Stalin to Gorbachev by Vladislav Zubok. UNC Press, 2007. ISBN 0-8078-3098-4; p. 58

- ^ Deportation of 1948–1953 Archived 2008-11-20 at the Wayback Machine. Azerbembassy.org.cn

- ^ Jump up to: a b Language Policy in the Soviet Union by Lenore A. Grenoble. Springer: 2003, p.135 ISBN 1-4020-1298-5

- ^ Central Asia: Its Strategic Importance and Future Prospects by Hafeez Malik. St. Martin's Press: 1994, p.149 ISBN 0-312-10370-0

- ^ Armenia: Political and Ethnic Boundaries 1878–1948 Archived 2007-09-26 at the Wayback Machine by Anita L. P. Burdett (ed.) ISBN 1-85207-955-X

- ^ (in Russian) All-Soviet Population Census of 1959 – Ethnic Composition in the Republics of the USSR: Armenian SSR. Demoscope.ru

- ^ (in Russian) All-Soviet Population Census of 1979 – Ethnic Composition in the Republics of the USSR: Armenian SSR. Demoscope.ru

- ^ Edmund Herzig, Marina Kurkchiyan. The Armenians: Past and Present in the Making of National Identity. Routledge, 2004; p. 216

- ^ Ronald Grigor Suny. Looking Toward Ararat: Armenia in Modern History. Indiana University Press, 1993; p. 184

- ^ Altstadt, Audrey. The Azerbaijani Turks: Power and Identity Under Russian Rule. Hoover Press, 1992; p. 187

- ^ (in Armenian) Isabella Sargsyan. About the Azeri Founder of Armenian Film Studies and Not Only. Epress.am. 15 October 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ^ "Jewish Armenia". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b (in Russian) The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict by Svante Cornell. Sakharov-Center.ru

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Lowell Barrington (ed.) After Independence: Making and Protecting the Nation in Postcolonial and Postcommunist States. University of Michigan Press, 2006. ISBN 0472025082; p. 230

- ^ Jump up to: a b (in Russian) Karabakh: Timeline of the Conflict. BBC Russian

- ^ Bolukbasi, Suha. Azerbaijan: A Political History. I.B.Tauris, 2011; ISBN 1848856202; p. 97.

- ^ Cornell, Svante E. The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict Archived 2013-04-18 at the Wayback Machine. Uppsala: Department of East European Studies, April 1999.

- ^ The Unrecognized IV. The Bitter Fruit of the 'Black Garden' Archived 2008-11-20 at the Wayback Machine by Yazep Abzavaty. Nashe Mnenie. 15 January 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2008

- ^ (in Russian) Pogroms in Armenia: Opinions, Conjecture and Facts. Interview with Head of the Armenian Committee for National Security Usik Harutyunyan. Ekspress-Khronika. #16. 16 April 1991. Retrieved 1 August 2008

- ^ "Əsir və itkin düşmüş, girov götürülmüş vətəndaşlarla əlaqədar Dövlət Komissiyası". www.human.gov.az.

- ^ "UNHCR U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Citizenship and Immigration Services Country Reports Azerbaijan. The Status of Armenians, Russians, Jews, and Other Minorities".

- ^ Country Reports on Human Rights Practices – 2004: Armenia. U.S. Department of State

- ^ Myths and Realities of Karabakh War by Thomas de Waal. Caucasus Reporting Service. CRS No. 177, 1 May 2003. Retrieved 31 July 2008

- ^ (in Russian) Renaming Towns in Armenia to Be Concluded in 2007. Newsarmenia.ru. 22

- ^ Nation and Politics in the Soviet Successor States by Ian Bremmer and Ray Taras. Cambridge University Press, 1993; p.270 ISBN 0-521-43281-2

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ghulyan, Husik (2020-12-01). "Conceiving homogenous state-space for the nation: the nationalist discourse on autochthony and the politics of place-naming in Armenia". Central Asian Survey. 0: 1–25. doi:10.1080/02634937.2020.1843405. ISSN 0263-4937.

- ^ Selected Groups of Minorities in Armenia (case study). ASA/MSDP. Yerevan, 2001.

- ^ How Many Azeris in Armenia Archived 2018-01-14 at the Wayback Machine. Armenia Today. 11 January 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ^ "The Azerbaijanis Residing in Armenia Don’t Want to Form an Ethnic Community" by Tatul Hakobyan. Hetq.am 26 February 2007

- ^ "Adam.az". web.archive.org. 6 July 2011.

Sources

- Bournoutian, George A. (1980). "The Population of Persian Armenia Prior to and Immediately Following its Annexation to the Russian Empire: 1826–1832". The Wilson Center, Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Kettenhofen, Erich; Bournoutian, George A.; Hewsen, Robert H. (1998). "EREVAN". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VIII, Fasc. 5. pp. 542–551.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). Historical Dictionary of Georgia (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1442241466.

External links

- Armenia and Azerbaijan: The Remaining by Zarema Valikhanova and Marianna Grigoryan

- "I Always Dream of Baku" by Alexei Manvelyan

- Azerbaijani diaspora

- Ethnic groups in Armenia

- Armenian Azerbaijanis

- Nagorno-Karabakh conflict