Bangor University

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2012) |

Welsh: Prifysgol Bangor | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Former names | University College of North Wales (1884–1996) University of Wales, Bangor (1996–2007) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motto | Welsh: Gorau Dawn Deall | ||||||||||||

Motto in English | "The Best Gift is Knowledge" | ||||||||||||

| Type | Public | ||||||||||||

| Established | 1884 | ||||||||||||

| Chancellor | George Meyrick | ||||||||||||

| Vice-Chancellor | Iwan Davies | ||||||||||||

Administrative staff | 2,000 | ||||||||||||

| Students | 9,945 (2019/20)[1] | ||||||||||||

| Undergraduates | 7,235 (2019/20)[1] | ||||||||||||

| Postgraduates | 2,715 (2019/20)[1] | ||||||||||||

| Location | Bangor , Wales 53°13′44″N 4°07′48″W / 53.2289°N 4.1301°WCoordinates: 53°13′44″N 4°07′48″W / 53.2289°N 4.1301°W | ||||||||||||

| Campus | Bangor | ||||||||||||

| Colours | |||||||||||||

| Nickname | Welsh: Y Coleg ar y Bryn ("The College on the Hill") | ||||||||||||

| Affiliations | EUA Universities UK University of Wales ACU HEA EIBFS | ||||||||||||

| Website | bangor.ac.uk | ||||||||||||

Bangor University (Welsh: Prifysgol Bangor) is a public university in Bangor, Wales. It received its Royal Charter in 1885 and was one of the founding institutions of the federal University of Wales. Officially known as University College of North Wales (UCNW), and later University of Wales, Bangor (UWB; Welsh: Prifysgol Cymru, Bangor), in 2007 it became Bangor University, independent from the University of Wales.

History[]

Early Years[]

The university was founded as the University College of North Wales (UCNW) on 18 October 1884, with an inaugural address by the Earl of Powis, the College's first President, in Penrhyn Hall.[2] There was then a procession to the college including 3,000 quarrymen (quarrymen from Penrhyn Quarry and other quarries had subscribed more than 1,200 pounds to the university).[3] The foundation was the result of a campaign for better provision of higher education in Wales that had involved some rivalry among towns in North Wales over which was to be the location of the new college.

The college was incorporated by Royal Charter in 1885.[2] Its students received degrees from the University of London until 1893, when UCNW became a founding constituent institution of the federal University of Wales.

During the Second World War paintings from national art galleries were stored in the Prichard-Jones Hall at UCNW to protect them from enemy bombing. They were later moved to slate mines at Blaenau Ffestiniog.[2] Students from University College, London, were evacuated to continue their studies in a safer environment at Bangor.[2]

Post-war[]

During the 1960s the university shared in the general expansion of higher education in the UK following the Robbins Report, with a number of new departments and new buildings.[2] On 22 November 1965, during construction of an extension to the Department of Electronic Engineering in Dean Street, a crane collapsed on the building. The three-ton counterweight hit the second-floor lecture theatre in the original building about thirty minutes before it would have been occupied by about 80 first-year students. The counterweight went through to the ground floor.[4]

In 1967 the Bangor Normal College, now part of the university, was the venue for lectures on Transcendental Meditation by the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi at which The Beatles heard of the death of their manager, Brian Epstein.[5]

Student protests at UCNW in the 1970s focused mainly on calls to expand the role of the Welsh language. Radical students would disturb lectures held in English and paint slogans in Welsh on the walls of the Main Building, resulting in a number of suspensions of these activists. In the early 1980s, the Thatcher government even considered closing down the institution.[2][6] Around this time consideration began of mergers with two colleges of education in Bangor: St Mary's College, a college for women studying to become schoolteachers, and the larger and older Normal College/Coleg Normal. The merger of St Mary's into UCNW was concluded in 1977, but the merger with Coleg Normal fell through in the 1970s and was not completed until 1996.

Name change[]

The 2007 change of name to Bangor University, or Prifysgol Bangor in Welsh, was instigated by the university following the decision of the University of Wales to change from a federal university to a confederal non-membership organisation, and the granting of degree-awarding powers to Bangor University itself. As a result, every student starting after 2009 gained a degree from Bangor University, while any student who started before 2009 had the option to have either Bangor University or University of Wales Bangor on their degree certificate.[7]

Recent Developments and Problems[]

Under John Hughes's leadership as Vice-Chancellor (2010–18), there were a number of new developments including the opening of St Mary's Student Village,[8] and the first ever collaboration between Wales and China to establish a new college, which involved Bangor University and the Central South University of Forestry and Technology (CSUFT).[9]

In 2014, Hughes took out a £45m loan from the European Investment Bank,[10][11] to assist the university in developing its estates strategy. In 2016, the university opened Marine Centre Wales,[12] a £5.5m building on the site of the university's Ocean Sciences campus in Menai Bridge, which was financed as part of the £25 million SEACAMS project, part funded through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).[13]

In May 2017, Bangor became the fourth Welsh university to review its cost base with a view to making savings of £8.5m.[14] The university responded and introduced a number of cost saving measures including a reorganization of the structure of Colleges and Schools and the introduction of a voluntary severance scheme, and the numbers of compulsory redundancies was reduced from the initial estimate of 170.[15][16] In addressing its financial challenges, Bangor University also reorganised some subject areas in 2017, which involved introducing new ways of co-ordinating and delivering adult education and part-time degree programmes,[17] continuing to teach archaeology, but discontinuing the single honours course,[18] and working with Grwp Llandrillo Menai to validate the BA Fine Art degree.[19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26]

Other issues which attracted adverse media comment included the cost overrun and delayed opening of the Pontio Arts and Innovation Centre in 2016,[27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34] the appointment of Hughes's then wife to a newly created senior management position,[35] the purchase and refurbishment of a house for the vice-chancellor by the university (costing the institution £750,000),[36][37][38][39] the expenses of some senior staff,[40][41][42] and the discrepancy between senior management salaries and remuneration for staff working on zero hour contracts.[43][44] In 2016, Hughes received a 7.5% pay rise and the university confirmed that this was the first increase that the vice-chancellor had received from the university's remuneration committee (of which Hughes himself was a member) since his appointment in 2010, although he would still have received an annual pay rise.[45]

From Hughes's takeover in 2010, when Bangor University made a £4.2 million profit, to 2017, the university's nominal income had risen by 12 per cent, but their expenditures by 19 per cent with the university's interests and finance costs (despite very low interest rates) soaring by 747 per cent.[46] In 2017/18, the university had to spend £10m in interest payments on its debts. From 2013/14 to 2017/18, Bangor University cut staff numbers from 1777.7 to 1608 FTE (minus 9.5 per cent). During the same period, student numbers grew from 10.646 to 11.156 (plus 4.8 per cent), increasing income from student fees.[47] In early 2019, an accountant who studied the university's finances on behalf of trade union criticised that the figures suggested spending had been diverted from staff costs to financing building projects.[48]

When a new financial crisis as well as allegations of Hughes's racist and sexist harassment against his ex-wife were revealed in late 2018 and the announced closure of the chemistry department and new staff cuts to save £5m sparked student protest, Bangor University announced Hughes's resignation by December 2018, eight months ahead of his ordinary retirement.[49][50][51][52][53][54]

Between 2017 and 2019, the university underwent three rounds of staff cuts.[55][52][56] Job insecurity as well as deteriorating working conditions and pension packages resulted in several strikes of university staff.[57][58][59][60][61][62] In June 2019, the university launched a plan to concentrate its non-residential estate onto a single campus in Bangor (Deiniol Road and College Road sites) and dispose of some major sites (including Normal Site, Dean Street and Fron Heulog), altogether 25 per cent of the estate.[63][64]

In September 2020, the university announced a new round of cuts to fill a £13m gap in the budget, saying 200 more jobs (including 80 academic posts) were at risk.[65][66][67][68][56][69][70][71] Another reorganization of the university's structure of Colleges and Schools was announced as well. Thereupon staff passed a motion of no confidence in the university management.[72]

Campus and buildings[]

The university occupies a substantial proportion of Bangor and also has part of its School of Healthcare Sciences in Wrexham.

Arts Building[]

The university was originally based in an old coaching inn, the Penrhyn Arms Hotel, which housed its 58 students and its 12 teaching staff. In 1911 it moved to a much larger new building, which is now the old part of the Main Arts Building. This building, designed by Henry Hare, had its foundation stone laid by King Edward VII on 9 July 1907, and was formally opened by King George V in 1911. The iconic building, which occupies a highly visible position overlooking Bangor, gave the college its Welsh nickname Y Coleg ar y Bryn ("The College on the Hill"). It included the large Prichard-Jones Hall, named after Sir John Prichard-Jones a local man who became a partner in the London department store Dickins & Jones, and was a substantial benefactor of the building.[2] The building became a Grade I listed building in 1949.[73]

A modern extension, completing a quadrangle on the College Road side of the building, was completed in 1969. This is now known as the Main Arts Building.

Halls of residence[]

The redbrick University Hall, built in a Queen Anne style, was the first substantial block. It was opened in 1897.[74] This building was to become the Welsh-language hall Neuadd John Morris-Jones in 1974, taking its name in honour of Professor John Morris Jones.[2] It is now called Neuadd Rathbone.

Neuadd Reichel, built on the Ffriddoedd Farm site, was designed in a neo-Georgian style by the architect Percy Thomas and was opened in 1942 as a hostel for male students.[2][74]

Expansion in the 1960s led to the development of Plas Gwyn in 1963–64 and Neuadd Emrys Evans in 1965, both on the Ffriddoedd site, and Neuadd Rathbone at the top of Love Lane in 1965.[2] Neuadd Rathbone, designed by and named after the second President of the college, was originally for women students only.[74] The names of Neuadd Rathbone and Neuadd John Morris-Jones were later exchanged. The building originally opened as Neuadd Rathbone is now known as Neuadd Garth.

Accommodation is guaranteed for all first-year undergraduate students at Bangor. There are around 3,000 rooms available in halls of residence, and all the accommodation is within walking distance of the university. There are three residential sites in current use: Ffriddoedd Village, St Mary's Village and Neuadd Garth.

Ffriddoedd Village []

The largest accommodation site is the Ffriddoedd Village in Upper Bangor, about ten minutes' walk from Top College, the Science Site and the city centre. This site has eleven en-suite halls completed in 2009, six other en-suite halls built in the 1990s and Neuadd Reichel built in the 1940s, and renovated in 2011.

Two of the en-suite halls, Bryn Dinas and Tegfan, now incorporate the new Neuadd John Morris-Jones, which started its life in 1974 on College Road and has, along with its equivalent Neuadd Pantycelyn in Aberystwyth, became a focal point of Welsh-language activities at the university. It is an integral part of UMCB, the Welsh Students' Union, which in turn is part of the main Students' Union.

The halls on "Ffridd" (ffridd [friːð] is the Welsh word for mountain pasture or sheep path; ffriddoedd [ˈfrɪðɔið] is its plural form) include Cefn y Coed, Glyder, Y Borth, Elidir, J.M.J. Bryn Dinas and J.M.J. Tegfan, all of which were built in the early 1990s; Adda, Alaw, Braint, Crafnant, Enlli, Peris, Glaslyn, Llanddwyn, Ffraw, Idwal and Gwynant, which were all built in the late 2000s; and Neuadd Reichel which was built in the 1940s and renovated in 2011. From 2021, Neuadd Reichel will no longer be used for student accommodation.

St Mary's Village []

Bryn Eithin overlooks the centre of Bangor and is close to the Science Departments and the Schools of Computer Science and Electronic Engineering. Demolition of the former St Mary's Site halls, with the exception of the 1902 buildings and the Quadrangle, began in 2014 to make way for new halls which were completed in 2015. The halls on this site are Cybi, Penmon, and Cemlyn, which are all self-catered flats; Tudno, which is a townhouse complex; and the original St. Mary's building, with studios and flats.[75]

In Welsh, bryn means "hill" and eithin means "gorse".

College Road[]

College Road has one hall, Neuadd Garth (formerly Neuadd John Morris Jones, before that Neuadd Rathbone), which is a self-catering hall. The site is located close to the Main Arts building in Upper Bangor. Neuadd Garth, after undergoing refurbishment in 2012–13, is now home to postgraduate students.

Neuadd Rathbone (formerly Neuadd John Morris Jones, before that University Hall), which is located on the site, was previously a hall of residence.

Private halls[]

A private hall of residence called Tŷ Willis House (formerly known as Neuadd Willis) is operated by iQ Student Accommodation; which incorporates the old listed British Hotel with a new extension to the rear, and a further hall on the site of the old Plaza Cinema. Other privately owned halls of residence in Bangor include Neuadd Kyffin, Neuadd y Castell, Neuadd Llys y Deon and Neuadd Tŷ Ni.

Students union[]

Undeb Bangor is Bangor University's Students' Union and was relocated to the brand new Arts and Innovation centre, Pontio, in 2016. Pontio includes a theatre, a cinema, a studio theatre and social facilities including the Undeb on the 4th floor.

The former Students' Union building was situated on Deiniol Road at one end of College Park below the Main Arts building. The Refectory and Curved Lounge were built in 1963[76] and the main administrative building was added in 1969. The building was known as Steve Biko House from the 1970s to the early 1990s,[2][77] after Steve Biko. The buildings were renovated in 1997 to create an 1,100-capacity nightclub, Amser/Time, where the previous refectory space was. Demolition of the Union buildings and Theatr Gwynedd began in July 2010.[78]

When the original Students' Union building was demolished, the Students' Union was relocated to Oswalds on Victoria Drive, before moving back to its original location on Deiniol Road in 2016.

Organisation[]

The Academic Activities of Bangor University are grouped into three colleges:

- College of Arts, Humanities and Business

- Bangor Business School

- School of History, Philosophy and Social Sciences

- School of Language, Literatures and Linguistics

- School of Law

- School of Music and Media

- School of Welsh and Celtic Studies

- Centre for Research on Bilingualism

- College of Environmental Sciences and Engineering

- School of Computer Science and Electronic Engineering

- School of Natural Sciences

- School of Ocean Sciences

- The BioComposites Centre

- College of Human Sciences

- School of Education and Human Development

- School of Health Sciences

- School of Medical Sciences

- School of Psychology

- School of Sport, Health and Exercise Sciences

Academic profile[]

Research[]

The university's research expertise in the areas of materials science and predictive modelling was enhanced during 2017 through a collaboration with Imperial College London and the formation of the Nuclear Futures Institute at Bangor with the award of £6.5m in funding under the Welsh Government's Ser Cymru programme.[79]

The university-owned £20m Science Park on Anglesey, M-Sparc was completed in March 2018, which will support the development of the region's low carbon energy sector.[80][81][82][83][84][85]

Rankings[]

| National rankings | |

|---|---|

| Complete (2022)[86] | 62 |

| Guardian (2021)[87] | 75 |

| Times / Sunday Times (2021)[88] | 62 |

| Global rankings | |

| ARWU (2021)[89] | 701–800 |

| CWTS Leiden (2021)[90] | 252 |

| QS (2022)[91] | 601-650 |

| THE (2022)[92] | 401–500 |

| British Government assessment | |

| Teaching Excellence Framework[93] | Gold |

The 2014 Research Excellence Framework recognised that more than three quarters of Bangor's research is either world-leading or internationally excellent. Based on the university submission of 14 Units of Assessment, 77% of the research was rated in the top two tiers of research quality, ahead of the average for all UK universities.[94]

In 2017, Bangor University became the only university in Wales to be rated 'Gold' by the new Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) which means that the university is deemed to be of the highest quality found in the UK, providing "consistently outstanding teaching, learning and outcomes for its students."[95][96]

In recent years, Bangor has been rated highly by its students in two independent surveys of student opinion. In the National Student Survey, the university has been consistently ranked highly both within Wales and in the UK higher education sector.[97] In 2017, Bangor University's students placed the university eighth among the UK's non-specialist universities and second among Welsh Universities.[98][third-party source needed]

For the second year in a row Bangor was awarded Best University in the UK for Clubs and Societies at the 2018 WhatUni Student Choice Awards. It also regained the award for best Student Accommodation which they originally won in 2016. The university was also placed second overall for 'Courses and Lecturers' and retained third place in the category 'University of the Year'. WhatUni award nominations are based on the reviews and opinions of the university's own students. This is the fourth year in a row that Bangor University has won a national WhatUni Award.[99][100][third-party source needed]

Student life[]

This section does not cite any sources. (June 2018) |

Students' union[]

The students' union provides services, support, activities and entertainment for students. All Bangor University students automatically become members of the students' union unless they choose to opt out. As with most if not all students' unions, a yearly election takes place in which a number of sabbatical officers are elected. These sabbatical officers are held accountable for the actions and decisions of the union, and often work closely with members of the Student Representative Council and other boards.

In January 2016 Bangor Students' Union moved into the new Pontio Arts and Innovation Centre, Deiniol Road, Bangor. The New Student Centre provides students with free Sports and Societies, as well as the chance to become a course rep.

Volunteering[]

The Students' Union offers more than 600 volunteering opportunities in 35 community-based projects, contributing a total of 600 hours to volunteering each week.

There is a long tradition of student volunteering in Bangor. The oldest records available detail the organisation of a tea party for local elderly residents in 1952. The Tea Party project continues to run to this day and is SVB's oldest project.

In October 2012 Student Volunteering Bangor was awarded the Queen's Award for Voluntary Service.

Bangor RAG (Raising and Giving) is a Student Volunteering Bangor project. The committee is made up of two coordinators and a number of committee members, plus several hundred "raggies". RAG collects money for two local and two national charities, which change every academic year and are chosen by the students. RAG members also regularly attend "raids" across the country and assist charities with one-off events throughout the year. Their mascot is a tiger named Rhodri RAG. In 1968, raggies surrepticiously carved a panda (then the RAG mascot) and the letters 'UCNW' into a chalk hillside in Wiltshire, causing considerable puzzlement in England.

Clubs and societies[]

There are more than 90 societies and over 50 sports clubs, ranging from academic societies to almost every sport imaginable. Notable sports include football (Bangor University F.C.), rowing (Bangor University Rowing Club), ultimate frisbee (Bangor University Ultimate Frisbee Club), fencing (Bangor University Fencing Club) and skateboarding (Bangor University Skate).

Student newspaper[]

Y Seren is the official English language student newspaper for Bangor University. Seren provides coverage for important student events such as the sabbatical officer elections and the annual Varsity sports competition. The newspaper is delivered monthly to the Ffriddoedd and St Mary's Villages, as well as to University buildings and local businesses. Seren also has a website, where every issue is archived. The newspaper's offices are located in the Pontio Arts Centre building.

Student radio[]

Storm FM is the official student radio station for Bangor University and is one of only three student radio stations in the UK with a long-term FM licence. The station is broadcast on 87.7FM from a low-powered FM transmitter based on the Ffriddoedd Site. The FM licence allows for broadcast to a very small area of Bangor, namely the Ffriddoed Road Halls of Residence. Storm FM went online in 2009.[101]

Trivia[]

In 2012, Bangor University topped a league table of student sex with undergraduates stating to have had an average number of 8.31 partners since starting university.[102]

Notable people associated with Bangor[]

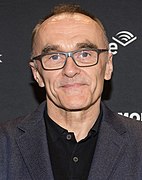

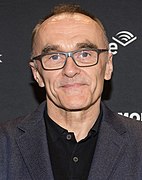

Danny Boyle

Stefan Rahmstorf

Presidents[]

- Edward Herbert, 3rd Earl of Powis, 1884–1891

- William Rathbone 1891–1900

- Lloyd Tyrell-Kenyon, 4th Baron Kenyon 1900–1927

- Herbert Gladstone, 1st Viscount Gladstone 1927–1935

- Lord Howard de Walden 1935–1940

- William Ormsby-Gore, 4th Baron Harlech 1940–1945

- Charles Paget, 6th Marquess of Anglesey 1945–1947

- Lloyd Tyrell-Kenyon, 5th Baron Kenyon 1947–1982

- William Mars-Jones 1982–1995

- Cledwyn Hughes 1995–2000

- Dafydd Elis-Thomas 2000–2017[2]

- George Meyrick 2017–present[103]

Vice Chancellors[]

The university has had seven Principals/Vice-Chancellors:

- Henry Reichel, Principal 1884–1927

- David Emrys Evans, Principal 1927–1958

- Charles Evans, Principal 1958–1984

- Eric Sunderland, Principal, Vice-Chancellor 1984–1995

- Roy Evans, Vice-Chancellor 1995–2004

- Merfyn Jones, Vice-Chancellor, 2004–2010

- John G Hughes, Vice-Chancellor 2010–2018[2]

- Graham Upton, Vice-Chancellor 2018–2019

- Iwan Davies, Vice-Chancellor 2019–present

Notable academics[]

- Samuel L. Braunstein, quantum physicist, 1997–2004

- Ronald Brown, English mathematician known for his work in algebraic topology

- Tony Conran, poet and translator, Reader in English and Tutor until 1983

- David Crystal, linguist and author, honorary professor of Linguistics

- A. H. Dodd, historian, 1919–1958

- Israel Dostrovsky (1918-2010), Russian (Ukraine)-born Israeli physical chemist, fifth president of the Weizmann Institute of Science

- John L. Harper, biologist, ecologist, British scholar and scientist, 1925-2009

- Raimund Karl, archaeologist, 2003–2020

- , historian, eighth director of the Swiss Social Archives, 2007–2014

- Bedwyr Lewis Jones, scholar

- William Mathias, composer, former professor of music

- John Morris-Jones, pioneering Welsh grammarian, editor, poet and literary critic

- Guto Puw, Welsh composer

- Duncan Tanner, historian of the Labour Party, 1989-2010

- John Meurig Thomas, Department of Chemistry

- Gwyn Thomas, Welsh scholar and poet

- Margaret Thrall, Welsh theologian and Anglican priest

Notable alumni[]

- Danny Boyle, film director and producer, graduate in English and drama

- Paul Bérenger, former Prime Minister of Mauritius[104]

- Martin J. Ball – Formerly Professor of Speech Language Pathology at Linköping University, Sweden.

- Frances Barber, Actress

- Richard Brunstrom (Chief Constable of North Wales Police), graduated in zoology (1979)[105]

- Gordon Conway, president of the Royal Geographical Society, and Vice Chancellor of the University of Sussex[106]

- Paul Alan Cox, ethnobotanist

- Colin Eaborn, Chemist

- Aled Eames – Warden of Neuadd Reichel in the 1950s and '60s and notable maritime historian. 1921–1996

- Robert G. Edwards, physiologist and pioneer in reproductive medicine, won the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.[107]

- John Evans, Film Director, graduated with a BA in Film Studies and an MA in Filmmaking

- Bill Fay, singer/musician and recording artist

- Raymond Garlick, Anglo-Welsh poet

- Tony Gillam, musician and writer

- Mary Dilys Glynne, plant pathologist

- Gwynn ap Gwilym, poet

- Lowri Gwilym, television and radio producer

- Tim Haines, BBC producer

- Julian Hibberd, Cambridge Plant Scientist, named by Nature as one of "Five crop researchers who could change the world"

- Howel Harris Hughes, theologian, Presbyterian minister and Principal of the United Theological College in Aberystwyth.[108]

- Siân James, Welsh traditional/folk singer and musician

- Ann Clwyd, Labour MP 1984 - 2019

- Einir Jones, poet

- Kathy Jones, Anglican priest and Dean of Bangor

- Martha Elizabeth Newton, bryologist and cytologist

- John Ogwen, actor

- R. Williams Parry, poet

- Tom Parry Jones, Inventor of electronic breathalyser

- Mmusi Maimane, South African Politician

- Stefan Rahmstorf, Professor of Physics of the Oceans at Potsdam University[109]

- Derek Ratcliffe (botanist, zoologist and nature conservationist)

- Howard Riley, jazz pianist and composer

- Gareth Roberts (physicist and university administrator)

- Kate Roberts, Welsh writer

- Andy Rowley (TV Producer)

- John Sessions (actor, original name John Marshall)

- Gwyn Thomas, Welsh scholar and poet

- R. S. Thomas (poet)

- Derick Thomson (Scottish Gaelic poet, publisher, academic and writer)

- Tim Wheeler, Vice-Chancellor of the University of Chester

- Roger Whittaker (musician)

- Bill Wiggin (Conservative MP for Leominster)

- Gareth Williams Former MI6

- Ifor Williams (historian of Welsh literature and editor of a number of medieval Welsh texts

- Herbert Wilson, DNA researcher

- Bethany C. Morrow, author

Fictional alumni[]

- According to Helen Fielding's 1996 novel Bridget Jones's Diary, the title character attended Bangor University.

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Where do HE students study?". Higher Education Statistics Agency. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m David Roberts (2009) Bangor University 1884–2009, University of Wales Press ISBN 978-0-7083-2226-0

- ^ The Times, Monday, 20 October 1884; pg. 7; Issue 31269; col F

- ^ The Guardian, 23 November 1965, p. 6.

- ^ "Higher Browsing: The Third Degree". The Guardian. 27 August 2002.

- ^ "Welsh language activist kicked out of Bangor University releases autobiography". The Bangor Aye. 24 November 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ University, Bangor. "Welcome - Student Administration - Bangor University". www.bangor.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2007.

- ^ University, Bangor. "St Mary's Village | Bangor University Accommodation". www.bangor.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ University, Bangor. "Partners sign agreement for first Wales-China College collaboration – News and Events, Bangor University". www.bangor.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Barry, Sion (2 April 2014). "Bangor University lands a £45m funding boost from the European Investment Bank".

- ^ "University upgrade wins £45m funding". BBC News. 2 April 2014.

- ^ Roberts, Joanne (13 July 2016). "Prince Charles opens Bangor University's Marine Centre Wales". northwales. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ University, Bangor. "HRH The Prince of Wales opens Marine Centre Wales at Bangor University – News and Events, Bangor University". www.bangor.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Wightwick, Abbie (14 May 2017). "Bangor Uni is reviewing spending which could lead to job losses". walesonline. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Hughes, Owen (21 October 2017). "Bangor University cuts the number of jobs under threat in restructure plans". northwales. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ "115 Bangor University staff face compulsory redundancy". BBC News. 29 June 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ University, Bangor. "Part-time courses at Bangor University". www.bangor.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ University, Bangor. "BA (Hons) History and Archaeology degree course". www.bangor.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Menai, Grwp Llandrillo. "BA (Hons) Fine Art - Grwp Llandrillo Menai". Grwp Llandrillo Menai - Coleg Llandrillo, Menai and Meirion-Dwyfor. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Brennan, Shane (10 December 2016). "Bangor University plans to axe night classes for adults".

- ^ "Bangor University: threat to Archaeology, Fine Art, and Lifelong Learning". 10 January 2017.

- ^ "Anger at "Ludicrous" Decision To Cut Archaeology BA At Bangor University Without Consultation - thePipeLine". thepipeline.info.

- ^ "Calls for fine arts course to continue". BBC News. 14 October 2018.

- ^ "Arfon AM's concerns for future of Bangor University's School of Life Long Learning".

- ^ "University to leave Archaeology in the past". 11 December 2016.

- ^ "Call for Participation: Prevent Closure of MA Women's Studies at Bangor – FWSA Blog". fwsablog.org.uk.

- ^ Thomas, Huw (9 April 2015). "'Chaotic' £49m arts centre delays". BBC News.

- ^ Crump, Eryl (3 November 2014). "Spiralling costs of Bangor University's Pontio centre could lead to job cuts".

- ^ "Arts centre delay cost university £1m". BBC News. 14 October 2018.

- ^ "Uni warned over £49m centre delays". BBC News. 3 November 2014.

- ^ Crump, Eryl (14 January 2016). "'Monstrosity' or challenging work of art? Have your say on Pontio work of art".

- ^ Ratcliffe, Rebecca (22 September 2015). "Sleepless students pay the price for university construction boom". The Guardian.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Crump, Eryl (14 January 2016). "This cost more than £100k to built - can you tell what it is?".

- ^ Shipton, Martin (18 October 2010). "Union criticises job for university head's wife".

- ^ "College buys new head £475k house". BBC News. 15 September 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Wyn-Williams, Gareth (27 May 2016). "Students' outrage at £250,000 makeover of uni boss's luxury pad".

- ^ "Uni pays for £168,000 home upgrade". BBC News. 27 May 2016.

- ^ Bennett, Rosemary (7 August 2017). "University chief living in luxury as staff face the axe" – via www.thetimes.co.uk.

- ^ Evans, Gareth (17 March 2015). "Bangor University criticised over director's £50k expenses".

- ^ "Bangor University Director in expenses scandal". 20 March 2015.

- ^ Wightwick, Abbie (14 June 2017). "University held a party at top Hong Kong hotel while making £8.5m cuts".

- ^ "Bangor University pension protest - News, Press release, Uncategorized - News - UNISON Cymru/Wales". 15 September 2016.

- ^ Evans, Gareth (9 April 2014). "Outrage as universities in Wales told: 'Justify six-figure vice-chancellor pay'".

- ^ Servini, Nick (18 October 2017). "Hikes in vice-chancellor pay revealed". BBC News. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ University, Bangor. "Bangor University Annual Accounts | Finance Office | Bangor University". www.bangor.ac.uk. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Facts and Figures | Planning and Student Data | Bangor University". www.bangor.ac.uk. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Wightwick, Abbie (17 January 2019). "University cuts staff as it faces £10m a year interest bill". walesonline.

- ^ Dec 13, The Bangor Aye; News, 2018 | Bangor; News, Bangor University (13 December 2018). "Calls for urgent meeting over Bangor University redundancies threat".

- ^ Dafydd, Aled ap (20 December 2018). "Uni head 'harassment' allegation revealed". BBC News.

- ^ Turner, Camilla (21 December 2018). "University vice-Chancellor 'boasted' to ex-wife's new husband: 'I had her in her youth and beauty'". The Telegraph – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Bangor University axes chemistry course and other jobs". BBC News. 10 April 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "TIMELINE: Redundancy, Retirement, Cuts & Chaos – Bangor University's End To 2018 As It Happened". Seren. 31 December 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "Students protest over Bangor University job cut plans". BBC News. 18 January 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "170 Bangor University jobs at risks to save £8.5m". BBC News. 7 June 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Bangor University accused of rushing into redundancy plans as 200 jobs put at risk". North.Wales. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "Lecturers to strike". Seren. 19 February 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "Bangor University Staff set for more strike action in February and March". The Bangor Aye. 5 February 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Wightwick, Abbie (4 February 2020). "University staff in Wales are going on strike again - this time for 14 days". WalesOnline. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Wightwick, Abbie (6 November 2019). "University staff will strike for eight days later this month". WalesOnline. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Wightwick, Abbie (25 November 2019). "University staff in Wales walk out over pay, pensions and working conditions". WalesOnline. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Wightwick, Abbie (15 April 2018). "Lecturers call off university strike action - but threat remains". WalesOnline. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "PROPOSAL: Bangor 2020-2030: Dean Street and Normal Site to close, SU and Academi to be moved". Seren. 5 June 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "Bangor University launch consultation on 10-year Estates Strategy". The Bangor Aye. 5 June 2019. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Wightwick, Abbie (7 October 2020). "University to cut 200 jobs as it faces huge funding shortfall". WalesOnline. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "Bangor University: 200 jobs at risk of redundancy". BBC News. 8 October 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "Bangor University Plans Cuts: the £13m gap in the budget". Seren. 21 September 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Hughes, Owen (7 October 2020). "Bangor University confirms which 200 jobs are set to go". North Wales Live. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "Money over morale? A look into Bangor's plans to cut 200 jobs". Seren. 19 October 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "What's on the chopping block? A school-by-school summary of the Bangor Business Cases". Seren. 26 October 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Hughes, Owen (10 September 2020). "200 jobs put at risk at Bangor University". Business Live. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "'No confidence' in Bangor University bosses over job cut plans". BBC News. 24 October 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ Bangor Civic Society. "Main Arts Building". Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c M L Clarke (1966) Architectural History and Guide, University College of North Wales Online at Bangor Civic Society

- ^ "St Mary's Student Halls Development – News and Events, Bangor University". bangor.ac.uk. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ "'Caernarvonshire Life' May 1964". Bangor Civic Society. Archived from the original on 15 January 2010. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ^ "'Seren' Published at Steve Biko House" (PDF). Seren. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ^ "Demolition Work Starts on the Old Theatr Gwynedd". Holyhead and Anglesey Mail. Archived from the original on 4 August 2010. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- ^ "Wales nuclear research centre opens". BBC News. 16 November 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ "Parc gwyddoniaeth i agor ar 1 Mawrth". BBC Cymru Fyw. 20 February 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ "Place North West | GALLERY I M-SParc brings science space to Wales". Place North West. 27 February 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ "New Managing Director". MSparcCMS. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ University, Bangor. "The Science of M-SParc; Delivered on time and budget. – News and Events, Bangor University". www.bangor.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Trewyn, Hywel (16 November 2017). "Wales' first nuclear research institute opens in Bangor". northwales. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ University, Bangor. "Bangor University opens the first nuclear research institute in Wales – News and Events, Bangor University". www.bangor.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ "Complete University Guide 2022". The Complete University Guide. 8 June 2021.

- ^ "Guardian University Guide 2021". The Guardian. 5 September 2020.

- ^ "Good University Guide 2021". The Times. 7 September 2020.

- ^ "Academic Ranking of World Universities 2021". Shanghai Ranking Consultancy. 15 August 2021.

- ^ "CWTS Leiden Ranking 2021 – PP top 10%". CWTS Leiden Ranking.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2022". Quacquarelli Symonds Ltd. 8 June 2021.

- ^ "THE World University Rankings 2022". Times Higher Education. 2 September 2021.

- ^ "Teaching Excellence Framework outcomes". Higher Education Funding Council for England.

- ^ University, Bangor. "Research at Bangor University". www.bangor.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ "One Welsh university rated 'gold'". BBC News. 22 June 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Roberts, Joanne (27 June 2017). "Bangor University rated gold for teaching". northwales. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ England, Higher Education Funding Council for. "National Student Survey results - Higher Education Funding Council for England". www.hefce.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ University, Bangor. "Satisfied students place Bangor University among top UK universities – News and Events, Bangor University". www.bangor.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ University, Bangor. "WhatUni Awards Success for Bangor University". www.bangor.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Roberts, Joanne (24 April 2018). "Bangor University rated best in UK for clubs and accommodation". northwales. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ "Storm 87.7FM: Bangor's Student Sound". Stormfm.com. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- ^ "Bangor University Students 'Have The Most Sex', Reveals StudentBeans 'Sex League'". Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ^ "George Meyrick announced as new Chancellor of Bangor University – News and Events, Bangor University". www.bangor.ac.uk.

- ^ "Mauritius: Into the Vacuum". Time. 15 June 1970 – via content.time.com.

- ^ "Police chief announces retirement". BBC News. 1 May 2009.

- ^ Harries-Rees, Karen (2006). "A man for change". Chemistry World. 3 (2): 42–44.

- ^ "The 2010 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine – Press Release". Nobelprize.org. 4 October 2010. Archived from the original on 5 October 2010. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

- ^ "HUGHES, HOWEL HARRIS (1873 - 1956), minister (Presb.), principal of the Theological College, Aberystwyth | Dictionary of Welsh Biography". biography.wales.

- ^ "Curriculum Vitae of Stefan Rahmstorf". www.pik-potsdam.de.

Further reading[]

- Clarke, M. L. (1966) Architectural History & Guide (University College of North Wales, Bangor); Online (Bangor Civic Society)

- Roberts, David (2009) Bangor University, 1884–2009. Cardiff: University of Wales Press ISBN 0-7083-2226-3

- Williams, J. Gwynn (1985) The University College of North Wales – Foundations 1884–1927. Cardiff: University of Wales Press ISBN 0-7083-0893-7

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bangor University. |

- Bangor University

- Universities in Wales

- Universities and colleges in North Wales

- University of Wales

- Educational institutions established in 1884

- Bangor, Gwynedd

- 1884 establishments in Wales

- Buildings by Henry Hare

- Universities established in the 19th century

- Law schools in Wales

- Universities UK