Bezbozhnik (newspaper)

22 April 1923 issue of Bezbozhnik | |

| Type | Daily newspaper |

|---|---|

| Format | Broadsheet |

| Founded | December 21, 1921 |

| Language | Russian |

| Ceased publication | January, 1935 |

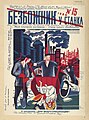

Cover showing the gods (of Judaism, Christianity and Islam) being crushed by the first five-year plan. | |

| Categories | Satirical magazine |

|---|---|

| Frequency | Monthly |

| Company | League of Militant Atheists |

| Country | Soviet Union |

| Language | Russian |

Bezbozhnik (Russian: Безбожник; "The Godless One") was an anti-religious and atheistic newspaper published in the Soviet Union between 1922 and 1941[1] by the League of Militant Atheists. Its first issue was published in December 1922, with a print run of 15,000, but its circulation reached as much as 200,000 in 1932.[2]

Between 1923 and 1931, there was also a magazine called Bezbozhnik u Stanka (Безбожник у станка; "The Godless One at the Workbench").[3] From 1928 to 1932 a magazine for peasants Derevenskiy Bezbozhnik (Деревенский безбожник; "The Rural Godless One") was published.[4] In 1928, one issue of the magazine Bezbozhnik za kul'turnuyu revolyutsiyu (Безбожник за культурную революцию; "The Godless One for the Cultural Revolution") was published.[5]

History[]

Initially, the publication ridiculed all religious belief as being a sign of ignorance and superstition, while stating that religion was dying in the officially atheist Soviet Union, with reports of closing churches, unemployed priests and ignored religious holidays. Starting in the mid-1920s, the Soviet government saw religion as an economic threat to the peasantry, whom, it said, were being oppressed by the clergy.[6]

Its main targets were Christianity and Judaism, accusing rabbis and priests of collaborating with the bourgeoisie and other counter-revolutionaries (see White movement). The rabbis were accused of promoting hostility between Jews and Gentiles. Bezbozhnik alleged that some rabbis in the tsarist government's pay had helped organize anti-Jewish pogroms, while claiming that such actions had sparked similar atrocities in England, South Africa and other countries.[3]

Priests were attacked as being parasites who lived off the work of the peasants. It reported about priests it said had admitted deceiving peasants and priests it said had renounced their profession. For instance, it ran a story about a certain Sergei Tomilin, who claimed 150 kilograms (3 cwt) of wheat and 21 metres (23 yards) of linen for each marriage he conducted, performing over 30 marriages in just a few weeks and thus receiving the wage a schoolteacher would have earned in 10 years.[6]

The magazine criticized the Jewish holiday of Passover as encouraging excessive drinking, because of the requirement of drinking four glasses of wine, while the Prophet Elijah was accused of being an alcoholic who got "drunk as a swine".[3]

Writer Mikhail Bulgakov once visited the offices of the Bezbozhnik and got a set of back numbers. He was shocked by its content, not only by what he called "boundless blasphemy", but also by its claims, such as that Jesus Christ was a rogue and a scoundrel. Bulgakov said that this was "a crime beyond measure".[7]

Bezbozhnik used humour as part of its anti-religious atheist propaganda, since humour was able to reach both educated and barely literate audiences. For example, in 1924, Bezbozhnik u Stanka issued a brochure called How to Build a Godless Corner, a tongue-in-cheek reference to the Eastern Orthodox's Icon Corner. The brochure included a set of two big posters with anti-religious slogans, seven other smaller humoristic posters, six back issues from Bezbozhnik u Stanka, from which to cut other images and instructions on how to assemble it. Such corners were suggested to be made at workplaces and their creator was encouraged to spend time at them and to try to convert other workers.[8]

Decline and termination[]

In 1932, with the Soviet economy faltering from economic dislocation associated with the first five-year plan, the Cultural Revolution was halted and a less extreme approach towards religion and other aspects of Soviet life was initiated by the regime.[9] Destabilizing campaigns in the economy, education, and social relations were halted and a move made towards the restoration of traditional values.[10] Bezbozhnik began to move away from its original subject, anti-religion and atheism, and began publishing more general political subjects.[6]

Membership in the League of the Militant Godless Ones, which had expanded during the Cultural Revolution to approximately 5 million plummeted to a few hundred thousand, bringing down the circulation of its newspaper in commensurate fashion.[10] The newspaper's circulation fell rapidly beginning in 1932 and was terminated completely in 1935.[10]

The League of the Militant Godless Ones was closed down in 1941, during World War II and the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany.[11]

Circulation[]

The newspaper Bezbozhnik launched on 21 December 1922.[12] During its first year of publication the paper's press run stood at 15,000 copies per issue.[13] The paper grew during the early years of the New Economic Policy, hitting the 100,000 mark in the summer of 1924 and topping 200,000 a year later.[13]

A decline followed from this early peak, with the press run of the publication tailing off to 114,000 in October 1925 and attenuating further to 90,000 in the fall of 1926.[13] This decline seems to have continued in subsequent months and the official press run was no longer publicized in the paper's pages from October 1926 through the first part of 1928, with a circulation of about 60,000 indicated by archival evidence.[13]

With the coming of the Cultural Revolution in 1929, Bezbozhnik was again the beneficiary of state promotion, with the circulation escalating to 400,000 in 1930.[13] With the move towards stabilization, the fall in circulation beginning in 1932 proved just as precipitous, with the publication being terminated in 1935.[10]

Bezbozhnyy Krokodil[]

Bezbozhnyy Krokodil (Russian: Безбожный крокодил; "Godless crocodile") is a satirical magazine. It was published in Moscow from 1924–1925 as a free satirical supplement to the newspaper „Bezbozhnik”. The responsible editor is Yemelyan Yaroslavsky.

“Bezbozhnyy Krokodil” appeared for the first time on January 13, 1924 on the pages No. 2 (55) of the newspaper “Bezbozhnik” as a special satirical section of the newspaper. The section occupied the upper halves of all four bands, had a clichéd headline, filled with sharp and topical feuilleton, fables, satirical poems and cartoons on anti-religious themes. Beginning February 10, 1924, with 5 (58) issues of the newspaper “Bezbozhnik”, “Bezbozhnyy Krokodil” is printed on a separate newspaper sheet, which is specially made up so that it can be folded into a notebook. The editors of “Bezbozhnik” invited their readers to cut out this sheet, fold it accordingly and stitch it together. In this form, “Bezbozhnyy Krokodil” acquired the character of an independent satirical publication that had a permanent clichéd heading, serial number, date of its publication, page numbering, its permanent departments and headings, etc.

The next 8 issues (No. 2–9) are published weekly starting February 10, along with regular issues of the newspaper “Bezbozhnik”. The publication of a special satirical supplement contributed to an even greater increase in the popularity of the newspaper among the masses, and led to a rapid increase in circulation. Within two months, the circulation of the newspaper and its satirical supplement grew from 34 to 210 thousand copies.

The wide popularity of the “Bezbozhnyy Krokodil” was due primarily to the fighting nature of anti-religious propaganda. Its popularity was greatly facilitated by the fact that the editorial staff skillfully used the various means of satire and humor. The pages of the magazine exposed the machinations of priests and churchmen, the fanaticism of sectarians, and a consistent struggle was conducted for the liberation of the working masses from religious durman. With no less merciless ridicule were the shortcomings in local anti-religious work, the tolerance of individual party and Soviet workers for clericalism, sectarianism, sorcery, prejudice and ignorance of part of the people, and especially the peasantry. Regularly published works in which the counter-revolutionary, reactionary role of the church was revealed, its connection with the exploiting classes, with capital.

The editors involved such satirists as Demyan Bedny, A. Zorich, S. Gorodetsky and others to collaborate in “Bezbozhnyy Krokodil”. M. Cheremnykh was in charge of the art department, whose drawings and cartoons were particularly sharp and inventive. Such permanent satirical sections and headings of the magazine as “Pitchfork to the flank”, “Crocodile's Tooth”, “Rayok”, “Readers Page”, were based, as a rule, on the materials of workers rural correspondents.

Since April 1924, the magazine is planned as a two-weekly. However, such a frequency is not maintained by the editors. The next issue of “Bezbozhnyy Krokodil” is only released on April 27, and the next on June 1. These issues no longer had serial numbers, although they were drawn up and printed, as before, on a single newspaper page. After the June issue, the publication of the “Bezbozhnyy Krokodil” is discontinued for more than a year.[14]

Examples of issues[]

"Anti-alcoholic" issue of Bezhbozhnik u stanka from 1929 portraying Jesus as a moonshiner

Bezhbozhnik u stanka issue from 1929 showing Jesus being dumped from a wheelbarrow by an industrial worker; the text suggests the Industrialization Day can be a replacement of the Christian Transfiguration Day.

See also[]

- Bezbozhnik (magazine)

- Bezbozhnik u Stanka

- Derevenskiy Bezbozhnik

- Antireligioznik

- Voinstvuiuschii ateizm

- Charlie Hebdo

- Atheist (magazine)

- Council for Religious Affairs

- Cultural Revolution (USSR)

- Demographics of the Soviet Union

- Persecutions of the Catholic Church and Pius XII

- Persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union

- Persecution of Christians in Warsaw Pact countries

- Persecution of Muslims in the former USSR

- Red Terror

- Religion in Russia

- Religion in the Soviet Union

- Society of the Godless

- Soviet Orientalist studies in Islam

- State atheism

- USSR anti-religious campaign (1917–1921)

- USSR anti-religious campaign (1921–1928)

- USSR anti-religious campaign (1928–1941)

- USSR anti-religious campaign (1958–1964)

- USSR anti-religious campaign (1970s–1990)

References[]

- ^ Salvatore Attardo (18 March 2014). Encyclopedia of Humor Studies. SAGE Publications. p. 472. ISBN 978-1-4833-4617-5. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ Milne (2004), p. 209

- ^ a b c Anna Shternshis, Soviet and Kosher: Jewish Popular Culture in the Soviet Union,1923-1939. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2006, p. 150-155.

- ^ Dimitry V. Pospielovsky. A History of Soviet Atheism in Theory, and Practice, and the Believer, vol 1: A History of Marxist-Leninist Atheism and Soviet Anti-Religious Policies, St Martin's Press, New York (1987) p. 62.

- ^ Orthodox Encyclopedia / «Безбожник» / Т. 4, С. 444-445

- ^ a b c Daniel Peris, Storming the Heavens: The Soviet League of the Militant Godless Ones. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998; pp. 75-76.

- ^ Lesley Milne, Bulgakov: The Novelist-playwright, Routledge, 1996; pg. 64.

- ^ Milne (2004), p. 128

- ^ Husband, "Godless Communists," pg. 159.

- ^ a b c d Husband, "Godless Communists," pg. 160.

- ^ Steven Merritt Miner, Stalin's Holy War: Religion, Nationalism, and Alliance Politics, 1941-1945. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2003; pg. 80.

- ^ William B. Husband, "Godless Communists": Atheism and Society in Soviet Russia, 1917-1932. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2000; pg. 60.

- ^ a b c d e Husband, "Godless Communists,'"' pg. 61.

- ^ Советская сатирическая печать 1917-1963 Стыкалин Сергей Ильич. Кременская Инна Кирилловна. «Безбожный крокодил»

Further reading[]

- William B. Husband, "Godless Communists": Atheism and Society in Soviet Russia, 1917-1932. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2000.

- Lesley Milne, Reflective Laughter: Aspects of Humour in Russian Culture, Anthem Press, 2004.

- Daniel Peris, Storming the Heavens: The Soviet League of the Militant Godless Ones. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1998.

- 1922 establishments in the Soviet Union

- 1941 disestablishments in the Soviet Union

- Magazines established in 1922

- Magazines disestablished in 1941

- Defunct magazines published in the Soviet Union

- Monthly magazines published in Russia

- Atheism publications

- Magazines published in the Soviet Union

- Russian-language magazines

- Satirical magazines published in Russia

- Propaganda in the Soviet Union

- Anti-religious campaign in the Soviet Union

- Anti-Christian sentiment in Europe

- Anti-Christian sentiment in Asia

- Propaganda newspapers and magazines

- Anti-Islam sentiment in Europe

- Anti-Islam sentiment in Asia

- Persecution of Muslims

- Religious persecution by communists