Biological Weapons Convention

| Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on their Destruction | |||

|---|---|---|---|

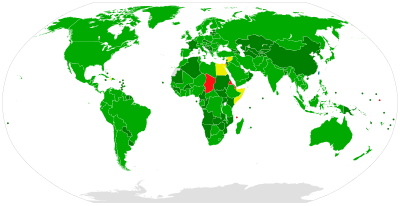

Participation in the Biological Weapons Convention

| |||

| Signed | 10 April 1972 | ||

| Location | London, Moscow, and Washington, D.C. | ||

| Effective | 26 March 1975 | ||

| Condition | Ratification by 22 states, including the three depositaries[1] | ||

| Signatories | 109 | ||

| Parties | 183[2] (complete list)

14 non-parties: Chad, Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt (signatory), Eritrea, Haiti (signatory), Israel, Kiribati, Micronesia, Namibia, Somalia (signatory), South Sudan, Syria (signatory), and Tuvalu. | ||

| Depositary | United States, United Kingdom, Russian Federation (successor to the Soviet Union)[3] | ||

| Languages | Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish[4] | ||

The Biological Weapons Convention (BWC), or Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention (BTWC), is a disarmament treaty that effectively bans biological and toxin weapons by prohibiting their development, production, acquisition, transfer, stockpiling and use.[5] The treaty's full name is the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxin Weapons and on their Destruction.[5]

Having entered into force on 26 March 1975, the BWC was the first multilateral disarmament treaty to ban the production of an entire category of weapons of mass destruction.[5] The Convention is of unlimited duration.[6] As of September 2021, 183 states have become party to the treaty.[7] Four additional states have signed but not ratified the treaty, and another ten states have neither signed nor acceded to the treaty.[8]

The BWC is considered to have established a strong global norm against biological weapons.[9] This norm is reflected in the treaty’s preamble, which states that the use of biological weapons would be "repugnant to the conscience of mankind".[10] It is also demonstrated by the fact that not a single state today declares to possess or seek biological weapons, or asserts that their use in war is legitimate.[11] In light of the rapid advances in biotechnology, biodefense expert Daniel Gerstein has described the BWC as "the most important arms control treaty of the twenty-first century".[12] However, the Convention’s effectiveness has been limited due to insufficient institutional support and the absence of any formal verification regime to monitor compliance.[13]

History[]

While the history of biological warfare goes back more than six centuries to the siege of Caffa in 1346,[14] international restrictions on biological warfare began only with the 1925 Geneva Protocol, which prohibits the use but not the possession or development of chemical and biological weapons.[15] Upon ratification of the Geneva Protocol, several countries made reservations regarding its applicability and use in retaliation.[16] Due to these reservations, it was in practice a "no-first-use" agreement only,[17] and in the two years from the onset of the US biological weapons program in 1943 through the end of World War II, the United States spent $400 million on biological weapons, mostly on research and development;[18] it came subsequently to light that other groups such as the Soviet Union had had a bioweapons program since two months after the convention in Geneva.[19]

Prior to the 1972 formation of the BWC, over four years from 1965, the Johnston Atoll (which was at the time under the dominion of the US) was subject to large-scale bioweapons development. The American strategic tests of bioweapons were as expensive and elaborate as the tests of the first hydrogen bombs at Eniwetok Atoll. They involved enough ships to have made the world's fifth-largest independent navy. One experiment involved a number of barges loaded with hundreds of rhesus monkeys; the experiment was a success and over half the monkeys died. It was estimated by the chief of product development for the United States Army's biological-warfare laboratories at Fort Detrick, Maryland that one jet with bioweapon spray "would probably be more efficient at causing human deaths than a ten-megaton hydrogen bomb."[20][21][22][23]

The American biowarfare system was terminated in 1969 by President Nixon at Fort Detrick when he issued his Statement on Chemical and Biological Defense Policies and Programs. The same day he gave a speech from the Roosevelt Room at the White House further outlining his earlier statement.[24][25] The statement ended, unconditionally, all U.S. offensive biological weapons programs.[26] When Nixon ended the program the budget was $300 million annually.[27][28]

The BWC sought to supplement the Geneva Protocol and was negotiated in the Conference of the Committee on Disarmament in Geneva from 1969 to 1972, following the conclusion of the negotiation of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.[29] Of significance was a 1968 British proposal to separate consideration of chemical and biological weapons and to first negotiate a convention on biological weapons.[29][30] The negotiations gained further momentum when the United States decided to unilaterally end its offensive biological weapons program in 1969 and support the British proposal.[31][32] In March 1971, the Soviet Union and its allies reversed their earlier opposition to the separation of chemical and biological weapons and tabled their own draft convention.[33][34] The final negotiation stage was reached when the United States and the Soviet Union submitted identical but separate drafts of the BWC text on 5 August 1971.[29] The BWC was opened for signature on 10 April 1972 with ceremonies in London, Moscow and Washington, D.C., and it entered into force on 26 March 1975 after the ratification by 22 states, including its three depositary governments (the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States).[29]

Certain scientists in the former Soviet Union including Ken Alibek were reported to have conducted "Gain-of-function research–like experiments" over a period of 20 years from 1972. The lab known as "Vektor" in Novosibirsk experimented on as many as 60,000 people as subjects for the research program on Ebola and another one on the Marburg virus. The Soviets also conducted programs on anthrax and the plague. "New features" were to be added to the bugs in order to make them more transmissible and pathogenic. Ebola virus genes were added in the Chimera project to the Vaccinia bug.[35] In 1992 after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russian President Boris Yeltsin admitted that they had violated the BWC.[36] The Chimera Project attempted in the late 1980s and early 1990s to combine DNA from Venezuelan equine encephalitis and smallpox at Obolensk, and Ebola virus and smallpox at Vektor. The existence of these chimeric viruses programmes was one reason why Alibek defected to the United States in 1992.[37] Journal articles by scientists suggest that in 1999 the experiments were still being continued.[38][39]

There have been some concerned scientists who have called for the modernization of the BWC at the periodic Review Conferences. For example, Filippa Lentzos and Gregory Koblentz pointed out in 2016 that "crucial contemporary debates about new developments" for the BWC Review Conferences included "gain-of-function experiments, , CRISPR and other genome editing technologies, gene drives, and synthetic biology".[40]

Treaty obligations[]

With only 15 articles, the BWC is relatively short. Over time, the treaty has been interpreted and supplemented by additional politically-binding agreements and understandings reached by its States Parties at eight subsequent Review Conferences.[42][43]

Summary of key articles[]

- Article I: Never under any circumstances to develop, produce, stockpile, acquire, or retain biological weapons.[44]

- Article II: To destroy or divert to peaceful purposes biological weapons and associated resources prior to joining.[45]

- Article III: Not to transfer, or in any way assist, encourage, or induce anyone else to acquire or retain biological weapons.[46]

- Article IV: To take any national measures necessary to implement the provisions of the BWC domestically.[47]

- Article V: Undertaking to consult bilaterally and multilaterally and cooperate in solving any problems which may arise in relation to the objective, or in the application, of the BWC.[48]

- Article VI: Right to request the United Nations Security Council to investigate alleged breaches of the BWC and undertaking to cooperate in carrying out any investigation initiated by the Security Council.[49]

- Article VII: To assist States which have been exposed to danger as a result of a violation of the BWC.[50]

- Article X: Undertaking to facilitate, and have the right to participate in, the fullest possible exchange of equipment, materials and information for peaceful purposes.[51]

The remaining articles concern the BWC's compatibility with the 1925 Geneva Protocol (Article VIII), negotiations to prohibit chemical weapons (Article IX), amendments (Article XI), Review Conferences (Article XII), duration (Article XIII, 1), withdrawal (Article XIII, 2), joining the Convention, depositary governments, and conditions for entry into force (Article XIV, 1-5), and languages (Article XV).[52]

Article I: Prohibition of biological weapons[]

Article I is the core of the BWC and requires each state "never in any circumstances to develop, produce, stockpile or otherwise acquire or retain:

- microbial or other biological agents, or toxins whatever their origin or method of production, of types and in quantities that have no justification for prophylactic, protective or other peaceful purposes;

- weapons, equipment or means of delivery designed to use such agents or toxins for hostile purposes or in armed conflict."[44]

Article I does not prohibit any specific biological agents or toxins as such but rather certain purposes for which they may be employed.[53] This prohibition is known as the general-purpose criterion and is also used in Article II, 1 of the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC).[54][55] The general-purpose criterion covers all hostile uses of biological agents, including those developed in the future,[54] and recognizes that biological agents and toxins are inherently dual use. While these agents may be employed for nefarious ends, they also have several legitimate peaceful purposes, including developing medicines and vaccines to counter natural or deliberate disease outbreaks.[53] Against this background, Article I only considers illegitimate those types and quantities of biological agents or toxins and their means of delivery which cannot be justified by prophylactic, protective, or other peaceful purposes; regardless of whether the agents in question affect humans, animals, or plants.[56] A disadvantage of this intent-based approach is a blurring of the line between defensive and offensive biological weapons research.[57]

While it was initially unclear during the early negotiations of the BWC whether viruses would be regulated by it since they lie "at the edge of life"—they possess some but not all of the characteristics of life—viruses were defined as biological agents in 1969 and thus fall within the BWC's scope.[58][59]

While Article I does not explicitly prohibit the "use" of biological weapons as it was already considered to be prohibited by the 1925 Geneva Protocol, it is still regarded as a violation of the BWC, as reaffirmed by the final document of the Fourth Review Conference in 1996.[60]

Article III: Prohibition of transfer and assistance[]

Article III bans the transfer, encouragement, assistance, or inducement of anyone, whether governments or non-state actors, in developing or acquiring any of the agents, toxins, weapons, equipment, or means of delivery specified in Article I.[46] The article’s objective is to prevent the proliferation of biological weapons by limiting the availability of materials and technology which may be used for hostile purposes.[53]

Article IV: National implementation[]

Article IV obliges BWC States Parties to implement the Convention’s provisions domestically.[47] This is essential to allow national authorities to investigate, prosecute, and punish any activities prohibited by the BWC; to prevent access to biological agents for harmful purposes; and to detect and respond to the potential use of biological weapons.[61] National implementing measures may take various forms, such as legislation, regulations, codes of conduct, and others.[62] Which implementing measures are adequate for a state depends on several factors, including its legal system, its size and geography, the development of its biotechnology industry, and its participation in regional economic cooperation. Since no one set of measures fits all states, the implementation of specific obligations is left to States Parties’ discretion, based on their assessment of what will best enable them to ensure compliance with the BWC.[63][64]

A database of over 1,500 laws and regulations that States Parties have enacted to implement the BWC domestically is maintained by the non-governmental organization VERTIC.[65] These concern the penal code, enforcement measures, import and export controls, biosafety and biosecurity measures, as well as domestic and international cooperation and assistance.[65] For instance, the 1989 Biological Weapons Anti-Terrorism Act implemented the Convention for the United States.[66] A 2016 VERTIC report concluded that there remain "significant quantitative gaps" in the BWC’s legislative and regulatory implementation since "many States have yet to adopt necessary measures to give effect to certain obligations".[67] The BWC’s Implementation Support Unit issued a background information document on "strengthening national implementation" in 2018[68] and an update in 2019.[69]

Article V: Consultation and cooperation[]

Article V requires States Parties to consult one another and cooperate in disputes concerning the purpose or implementation of the BWC.[48] The Second Review Conference in 1986 agreed on procedures to ensure that alleged violations of the BWC would be promptly addressed at a consultative meeting when requested by a State Party.[70] These procedures were further elaborated by the Third Review Conference in 1991.[56] One formal consultative meeting has taken place, in 1997 at the request of Cuba.[53][71]

Article VI: Complaint about an alleged BWC violation[]

Article VI allows States Parties to lodge a complaint with the United Nations Security Council if they suspect a breach of treaty obligations by another state.[49] Moreover, the article requires states to cooperate with any investigation which the Security Council may launch.[49] As of September 2021, no state has ever used Article VI to file a formal complaint, despite several states having been accused in other fora of maintaining offensive biological weapons capabilities.[72] The unwillingness to invoke Article VI may be explained by the highly political nature of the Security Council, where the five permanent members—China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States—hold veto power, including over investigations for alleged treaty violations.[73][72]

Article VII: Assistance after a BWC violation[]

Article VII obliges States Parties to provide assistance to states that so request it if the UN Security Council decides they have been exposed to danger as a result of a violation of the BWC.[50] In addition to helping victims in the event of a biological weapons attack, the purpose of the article is to deter such attacks from occurring in the first place by reducing their potential for harm through international solidarity and assistance.[32] Despite no state ever having invoked Article VII, the article has drawn more attention in recent years, in part due to increasing evidence of terrorist organizations being interested in acquiring biological weapons and also following various naturally occurring epidemics.[11] In 2018, the BWC’s Implementation Support Unit issued a background document describing a number of additional understandings and agreements on Article VII that have been reached at past Review Conferences.[74]

Article X: Peaceful cooperation[]

Article X protects States Parties’ right to exchange biological materials, technology, and information to be used for peaceful purposes.[51] The article states that the implementation of the BWC shall avoid hampering the economic or technological development of States Parties or peaceful international cooperation on biological projects.[51] The Seventh Review Conference in 2011 established an Article X database, which matches voluntary requests and offers for assistance and cooperation among States Parties and international organizations.[75]

Membership and joining the BWC[]

The BWC has 183 States Parties as of September 2021, with Tanzania the most recent to become a party.[7] Four states have signed but not ratified the treaty: Egypt, Haiti, Somalia, and Syria.[7] Ten additional states have neither signed nor acceded to the treaty: Chad, Comoros, Djibouti, Eritrea, Israel, Kiribati, Micronesia, Namibia, South Sudan and Tuvalu.[7] For three of these 14 states not party to the Convention, the process of joining is well advanced, while an additional five states have started the process.[8] The BWC’s degree of universality remains low compared to other weapons of mass destruction regimes, including the Chemical Weapons Convention with 193 parties[76] and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty with 191 parties.[77]

States can join the BWC through either ratification, accession or succession, in accordance with their national constitutional processes, which often require parliamentary approval.[78] Ratification applies to states which had previously signed the treaty before it entered into force in 1975.[78] Since then, signing the treaty is no longer possible, but states can accede to it.[78] Succession concerns newly independent states that accept to be bound by a treaty that the predecessor state had joined.[78] The Convention enters into force on the date when an instrument of ratification, accession, or succession is deposited with at least one of the depositary governments (the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom, and the United States).[78]

Several countries made reservations when ratifying the BWC declaring that it did not imply their complete satisfaction that the treaty allows the stockpiling of biological agents and toxins for "prophylactic, protective or other peaceful purposes", nor should it imply recognition of other countries they do not recognize.[7]

Verification and compliance[]

Confidence-building measures[]

At the Second Review Conference in 1986, BWC States Parties agreed to strengthen the treaty by exchanging annual confidence-building measures (CBMs).[70][80] These politically-binding[81] reports aim to prevent or reduce the occurrence of ambiguities, doubts and suspicions, and at improving international cooperation on peaceful biological activities.[70] CBMs are the main formal mechanism through which States Parties regularly exchange compliance-related information.[81] After revisions by the Third, Sixth, and Seventh Review Conferences, the current CBM form requires states to provide information annually on six issues (CBM D was deleted by the Seventh Review Conference in 2011):[80]

- CBM A: (i) research centres and laboratories, and (ii) national biological defence research and development programs

- CBM B: outbreaks of infectious diseases and similar occurrences caused by toxins

- CBM C: efforts to promote research results

- CBM E: legislation, regulations, and other measures

- CBM F: past activities in offensive and/or defensive biological research and development programs

- CBM G: vaccine production facilities

While the number of CBM submissions has increased over time, the overall participation rate remains low at less than 50 percent.[79] In 2018, an online CBM platform was launched to facilitate the electronic submission of CBM reports.[79] An increasing number of states are making their CBM reports publicly available on the platform, but many reports remain only accessible to other states.[81] The history and implementation of the CBM system have been described by the BWC Implementation Support Unit in a 2016 report to the Eighth Review Conference.[82]

Failed negotiation of a verification protocol[]

Unlike the chemical or nuclear weapons regimes, the BWC lacks both a system to verify states’ compliance with the treaty and a separate international organization to support the Convention’s effective implementation.[53] Agreement on such a system was not feasible at the time the BWC was negotiated, largely due to Cold War politics[17] but also due to a belief it was not necessary and that the BWC would be difficult to verify. U.S. biological weapons expert Jonathan B. Tucker commented that "this lack of an enforcement mechanism has undermined the effectiveness of the BWC, as it is unable to prevent systematic violations".[13]

Earlier drafts of the BWC included limited provisions for addressing compliance issues, but these were removed during the negotiation process. Some countries attempted to reintroduce these provisions when the BWC text was submitted to the General Assembly in 1971 but were unsuccessful, as were attempts led by Sweden at the First Review Conference in 1980.[83]

Following the end of the Cold War, a long negotiation process to add a verification mechanism began in 1991, when the Third Review Conference established an expert group on verification, VEREX, with the mandate to identify and examine potential verification measures from a scientific and technical standpoint.[56][84] During four meetings in 1992 and 1993, VEREX considered 21 verification measures, including inspections of facilities, monitoring relevant publications, and other on-site and off-site measures.[85] Another stimulus came from the successful negotiation of the Chemical Weapons Convention, which opened for signature in 1993.[76]

Subsequently, a Special Conference of BWC States Parties in 1994 considered the VEREX report and decided to establish an Ad Hoc Group to negotiate a legally-binding verification protocol.[86] The Ad Hoc Group convened 24 sessions between 1995 and 2001, during which it negotiated a draft protocol to the BWC which would establish an international organization and introduce a verification system.[72] This organization would employ inspectors who would regularly visit declared biological facilities on-site and could also investigate specific suspect facilities and activities.[72] Nonetheless, states found it difficult to agree on several fundamental issues, including export controls and the scope of on-site visits.[72] By early 2001, the "rolling text" of the draft protocol still contained many areas on which views diverged widely.

In March 2001, a 210-page draft protocol was circulated by the chairman of the Ad Hoc Group, which attempted to resolve the contested issues.[87] However, at the 24th session of the Ad Hoc Group in July 2001 the George W. Bush administration rejected both the draft protocol circulated by the Group’s Chairman and the entire approach on which the draft was based, resulting in the collapse of the negotiation process.[88][17] To justify its decision, the United States asserted that the protocol would not have improved BWC compliance and would have harmed U.S. national security and commercial interests.[89] Many analysts, including Matthew Meselson and Amy Smithson, criticized the U.S. decision as undermining international efforts against non-proliferation and as contradicting U.S. government rhetoric regarding the alleged biological weapons threat posed by Iraq and other U.S. adversaries.[90]

In subsequent years, calls for restarting negotiations on a verification protocol have been repeatedly voiced. For instance, during the 2019 Meeting of Experts "several States Parties stressed the urgency of resuming multilateral negotiations aimed at concluding a non-discriminatory, legally-binding instrument dealing with (...) verification measures".[91] However, since "some States Parties did not support the negotiation of a protocol to the BWC" it seems "neither realistic nor practicable to return to negotiations".[91]

Non-compliance[]

A number of BWC States Parties have been accused of breaching the Convention’s obligations by developing or producing biological weapons. Because of the intense secrecy around biological weapons programs,[32] it is challenging to assess the actual scope of biological activities and whether they are legitimate defensive programs or a violation of the Convention—except for a few cases with an abundance of evidence for offensive development of biological weapons.[13]

Soviet Union[]

Despite being a party and depositary to the BWC, the Soviet Union has operated the world’s largest, longest, and most sophisticated biological weapons program, which goes back to the 1920s under the Red Army.[92][37] Around the time when the BWC negotiations were finalized, and the treaty was signed in the early 1970s, the Soviet Union significantly expanded its covert biological weapons program under the oversight of the "civilian" institution Biopreparat within the Soviet Ministry of Health.[93] The Soviet program employed up to 65,000 people in several hundred facilities[92] and successfully weaponized several pathogens, such as those responsible for smallpox, tularemia, bubonic plague, influenza, anthrax, glanders, and Marburg fever.[13]

The Soviet Union first drew much suspicion of violating its obligations under the BWC after an unusual anthrax outbreak in 1979 in the Soviet city of Sverdlovsk resulted in the deaths of approximately 65 to 100 people.[94][95] The Soviet authorities blamed the outbreak on the consumption of contaminated meat and for years denied any connection between the incident and biological weapons research.[95][96] However, investigations concluded that the outbreak was caused by an accident at a nearby military microbiology facility, resulting in the escape of an aerosol of anthrax pathogen.[95][96][97] Supporting this finding, Russian President Boris Yeltsin later admitted that "our military developments were the cause".[98]

Western concerns about Soviet compliance with the BWC increased during the late 1980s and were supported by information provided by several defectors, including Vladimir Pasechnik and Ken Alibek.[92][37] American President George H. W. Bush and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher therefore directly challenged President Gorbachev with the information. After the Soviet Union’s dissolution, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Russia concluded the Trilateral Agreement on 14 September 1992, reaffirming their commitment to full compliance with the BWC and declaring that Russia had eliminated its inherited offensive biological weapons program.[99] The agreement’s objective was to uncover details about the Soviet’s biological weapons program and to verify that all related activities had truly been terminated.[99]

David Kelly, a British expert on biological warfare and participant in the visits arranged under the Trilateral Agreement, concluded that, on the one hand, the agreement "was a significant achievement" in that it "provided evidence of Soviet non-compliance from 1975 to 1991"; on the other hand, Kelly noted that the Trilateral Agreement "failed dramatically" because Russia did not "acknowledge and fully account for either the former Soviet programme or the biological weapons activities that it had inherited and continued to engage in".[99]

Milton Leitenberg and Raymond Zilinskas, authors of the 2012 book The Soviet Biological Weapons Program: A History, assert that Russia may still continue parts of the Soviet biological weapons program today.[92]

Iraq[]

Starting around 1985 under Saddam Hussein's leadership, Iraq weaponized anthrax, botulinum toxin, aflatoxin, and other agents,[100] and created delivery vehicles, including bombs, missile warheads, aerosol generators, and spray systems.[53] Thereby, Iraq breached the provisions of the BWC, which it had signed in 1972, although it only ratified the Convention in 1991 as a condition of the cease-fire agreement that ended the 1991 Gulf War.[101][7] The Iraqi biological weapons program—along with its chemical weapons program—was uncovered after the Gulf War through the investigations of the United Nations Special Commission (UNSCOM), which was responsible for disarmament in post-war Iraq.[53] Iraq deliberately obstructed, delayed, and deceived the UNSCOM investigations and only admitted to having operated an offensive biological weapons program under significant pressure in 1995.[101] While Iraq maintained that it ended its biological weapons program in 1991, many analysts believe that the country violated its BWC obligations by continuing the program until at least 1996.[102][103]

Other accusations of non-compliance[]

In April 1997, Cuba invoked the provisions of Article V to request a formal consultative meeting to consider its allegations that the United States introduced the crop-eating insect Thrips palmi to Cuba via crop-spraying planes in October 1996.[71][104] Cuba and the United States presented evidence for their diverging views on the incident in a formal consultation in August 1997. Having reviewed the evidence, twelve States Parties submitted reports, of which nine concluded that the evidence did not support the Cuban allegations, and two (China and Vietnam) maintained it was inconclusive.[53]

At the Fifth BWC Review Conference in 2001, the United States charged four BWC States Parties—Iran, Iraq, Libya, and North Korea—and one signatory, Syria, with operating covert biological weapons programs.[17][53] Moreover, a 2019 report from the U.S. Department of State raises concerns regarding BWC compliance in China, Russia, North Korea, and Iran.[105] The report concluded that North Korea "has an offensive biological weapons program and is in violation of its obligations under Articles I and II of the BWC" and that Iran "has not abandoned its (...) development of biological agents and toxins for offensive purposes".[105]

In recent years, Russia has repeatedly alleged that the United States is supporting and operating biological weapons facilities in the Caucasus and Central Asia, in particular the Richard Lugar Center for Public Health Research in the Republic of Georgia.[106][107] The U.S. Department of State called these allegations "groundless" and reaffirmed that "all U.S. activities (...) [were] consistent with the obligations set forth in the Biological Weapons Convention".[108] Biological weapons expert Filippa Lentzos agreed that the Russian allegations are "unfounded" and commented that they are "part of a disinformation campaign".[109] Similarly, Swedish biodefense specialists Roger Roffey and Anna-Karin Tunemalm called the allegations "a Russian propaganda tool".[110]

Implementation Support Unit[]

After a decade of negotiations, the major effort to institutionally strengthen the BWC failed in 2001, which would have resulted in a legally binding protocol to establish an Organization for the Prohibition of Biological Weapons (OPBW).[53][87] Against this background, the Sixth Review Conference in 2006 created an Implementation Support Unit (ISU) funded by the States Parties to the BWC and housed in the Geneva Branch of the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs.[111][112] The unit’s mandate is to provide administrative support, assist the national implementation of the BWC, encourage the treaty’s universal adoption, pair assistance requests and offers, and oversee the confidence-building measures process.[111]

With a staff size of only three and a budget smaller than the average McDonald’s restaurant,[113] the ISU does not compare with the institutions established to deal with chemical or nuclear weapons. For example, the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) has about 500 employees,[114] the International Atomic Energy Agency employs around 2,600 people,[115] and the CTBTO Preparatory Commission employs around 280 staff.[116]

Review Conferences[]

States Parties have formally reviewed the operation of the BWC at periodic Review Conferences held every five years; the first took place in 1980.[117] The objective of these conferences is to ensure the effective realization of the Convention’s goals and, in accordance with Article XII, to "take into account any new scientific and technological developments relevant to the Convention".[40][118] Most Review Conferences have adopted additional understandings or agreements that have interpreted or elaborated the meaning, scope, and implementation of BWC provisions.[42] These additional understandings are contained in the final documents of the Review Conferences and in an overview document prepared by the BWC Implementation Support Unit for the Eighth Review Conference in 2016.[43]

| Review Conference | Date | Key outcomes and issues | BWC States Parties | Chairperson | Final Document |

| First[83] | 3. – 21. March 1980 | 1. Encouragement of voluntary declarations of (i) past possession of BWC-relevant items, (ii) efforts to destroy or divert these items to peaceful purposes, (iii) and enactment of national legislation to implement the Convention.

2. Elaboration of the cooperation under Article X by including personnel training, information exchange, and the transfer of materials and equipment. |

87 | Ambassador Oscar Vaerno (Norway) | BWC/CONF.I/10 |

| Second[70] | 8. – 26. September 1986 | 1. Agreement on the annual exchange of confidence-building measures (CBMs), including information on (i) high-containment research laboratories, (ii) abnormal infectious disease outbreaks, and (iii) the encouragement of BWC-relevant research in publicly available journals.

2. Bringing bioterrorism within the Convention’s scope by agreeing that it applies to all international, national and non-State actors and that it covers all relevant current and future scientific and technological developments. 3. Strengthening of Article V by agreeing on the Formal Consultative Process, a procedure to resolve doubts about compliance through consultative meetings. 4. Agreement that the World Health Organization would coordinate the emergency response in the event of suspected biological and toxin weapons use. |

103 | Ambassador Winfried Lang (Austria) | BWC/CONF.II/13 |

| Third[56] | 9. – 27. September 1991 | 1. Expansion of the CBMs by including information on (i) national implementation measures such as legislation, (ii) past offensive and defensive biological weapons programs, and (iii) vaccine production facilities.

2. Establishment of an expert group on verification, VEREX, mandated to identify and examine potential verification measures from a scientific and technical standpoint. 3. Clarification that investigations under Article VI can also be requested through the Secretary-General and not only through the Security Council. 4. Reaffirmation that the BWC covers not just agents affecting humans but also those affecting animals and plants. 5. Clarification of the coordinating role of intergovernmental organizations responding to attacks allegedly involving biological weapons. 6. Assertion that information on the implementation of Article X on peaceful uses of the biological sciences should also be provided to the United Nations. |

116 | Ambassador Roberto Garcia Moritan (Argentina) | BWC/CONF.III/23 |

| Fourth[60] | 25. November – 6. December 1996 | 1. Reaffirmation that the use of biological weapons is considered prohibited under Article I.

2. Assertion that the destruction and conversion of former biological weapons and associated facilities should be completed before accession to the BWC. 3. Recommendation of specific measures to improve the implementation of Article X on peaceful uses of the biological sciences. |

135 | Ambassador Sir Michael Weston (U.K.) | BWC/CONF.IV/9 |

| Fifth[119] | 19. November – 7. December 2001;

11. – 22. November 2002 |

1. Suspension of the conference by one year in response to the U.S. proposal to terminate the Ad Hoc Group’s mandate.

2. Establishment of an intersessional program, including annual Meetings of States Parties and Meetings of Experts, to promote discussion and agreement on a variety of topic relevant to the BWC. |

144 | Ambassador Tibor Toth (Hungary) | BWC/CONF.V/17 |

| Sixth[112] | 20. November – 8. December 2006 | 1. Establishment of the BWC Implementation Support Unit within the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs in Geneva to provide administrative support and strengthen the Convention in other ways.

2. Renewal and modification of the intersessional program. |

155 | Ambassador Masood Khan (Pakistan) | BWC/CONF.VI/6 |

| Seventh[120] | 5. – 22. December 2011 | 1. Revision of the CBM reporting forms, including the deletion of CBM form D on the active promotion of contacts.

2. Establishment of a database to facilitate assistance and cooperation under Article X.[121] 3. Establishment of a sponsorship program to support developing States Parties to participate in the annual BWC meetings.[122] 4. Reform of the Convention’s financing system. |

165 | Ambassador Paul van den IJssel (Netherlands) | BWC/CONF.VII/7 |

| Eighth[123] | 7. – 25. November 2016 | 1. Renewal of the ISU’s mandate, the sponsorship program, the intersessional program, and the Article X assistance and cooperation database. | 177 | Ambassador (Hungary) | BWC/CONF.VIII/4 |

| Ninth[124] | TBA | 1. Review the operation of the Convention, taking into account the new scientific and technological developments relevant to the Convention. 2. Progress made by States Parties on the implementation of the Convention, and 3. Progress of the implementation of decisions and recommendations agreed upon at the Eighth Review Conference. | 183 | Ambassador Cleopa K Mailu (Kenya) | None |

Intersessional program[]

As agreed at the Fifth Review Conference in 2001/2002, annual BWC meetings have been held between Review Conferences starting in 2003, referred to as the intersessional program.[119][125] The intersessional program includes both annual Meetings of States Parties (MSP)—aiming to discuss, and promote common understanding and effective action on the topics identified by the Review Conference—as well as Meetings of Experts (MX), which serve as preparation for the Meeting of States Parties.[119][117] The annual meetings do not have the mandate to adopt decisions, a privilege reserved for the Review Conferences which consider the results from the intersessional program.[11]

| Intersessional program period | Duration | Topics |

|---|---|---|

| 2003 – 2005[119] | MSP: 1 week

MX: 2 weeks |

1. the adoption of necessary national measures to implement the prohibitions set forth in the Convention, including the enactment of penal legislation

2. national mechanisms to establish and maintain the security and oversight of pathogenic microorganisms and toxins 3. enhancing international capabilities for responding to, investigating and mitigating the effects of cases of alleged use of biological or toxin weapons or suspicious outbreaks of disease 4. strengthening and broadening national and international institutional efforts and existing mechanisms for the surveillance, detection, diagnosis and combating of infectious diseases affecting humans, animals, and plants 5. the content, promulgation, and adoption of codes of conduct for scientists |

| 2007 – 2010[112] | MSP: 1 week

MX: 1 week |

1. Ways and means to enhance national implementation, including enforcement of national legislation, strengthening of national institutions and coordination among national law enforcement institutions

2. Regional and sub-regional cooperation on implementation of the Convention 3. National, regional and international measures to improve biosafety and biosecurity, including laboratory safety and security of pathogens and toxins 4. Oversight, education, awareness raising, and adoption and/or development of codes of conduct with the aim of preventing misuse in the context of advances in bio-science and bio-technology research with the potential of use for purposes prohibited by the Convention 5. With a view to enhancing international cooperation, assistance and exchange in biological sciences and technology for peaceful purposes, promoting capacity building in the fields of disease surveillance, detection, diagnosis, and containment of infectious diseases: (1) for States Parties in need of assistance, identifying requirements and requests for capacity enhancement; and (2) from States Parties in a position to do so, and international organizations, opportunities for providing assistance related to these fields 6. Provision of assistance and coordination with relevant organizations upon request by any State Party in the case of alleged use of biological or toxin weapons, including improving national capabilities for disease surveillance, detection and diagnosis and public health systems |

| 2012 – 2015[120] | MSP: 1 week

MX: 1 week |

1. Cooperation and assistance, with a particular focus on strengthening cooperation and assistance under Article X

2. Review of developments in the field of science and technology related to the Convention 3. Strengthening national implementation 4. How to enable fuller participation in the CBMs 5. How to strengthen implementation of Article VII, including consideration of detailed procedures and mechanisms for the provision of assistance and cooperation by States Parties |

| 2018 – 2020[123] | MSP: 4 days

MX: 5 separate meetings across 8 days |

1. Cooperation and assistance, with a particular focus on strengthening cooperation and assistance under Article X

2. Review of developments in the field of science and technology related to the Convention 3. Strengthening national implementation 4. Assistance, response and preparedness 5. Institutional strengthening of the Convention |

Challenges[]

Potential misuse of rapid scientific and technological developments[]

Advances in science and technology are relevant to the BWC since they may affect the threat presented by biological weapons. The ongoing advances in synthetic biology and enabling technologies are eroding the technological barriers to acquiring and genetically enhancing dangerous pathogens and using them for hostile purposes.[126] For example, a 2019 report by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute finds that "advances in three specific emerging technologies—additive manufacturing (AM), artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics—could facilitate, each in their own way, the development or production of biological weapons and their delivery systems".[126] Similarly, biological weapons expert Filippa Lentzos argues that the convergence of genomic technologies with "machine learning, automation, affective computing, and robotics (...) [will] create the possibility of novel biological weapons that target particular groups of people and even individuals".[127] On the other hand, these scientific developments may improve pandemic preparedness by strengthening prevention and response measures.[126][128]

Technological challenges in the verification of biological weapons[]

There are several reasons why biological weapons are especially difficult to verify. First, in contrast to chemical and nuclear weapons, even small initial quantities of biological agents can be used to quickly produce militarily significant amounts.[129] Second, biotechnological equipment and even dangerous pathogens and toxins cannot be prohibited altogether since they also have legitimate peaceful or defensive purposes, including the development of vaccines and medical therapies.[129] Third, it is possible to rapidly eliminate biological agents, which makes short-notice inspections less effective in determining whether a facility produces biological weapons.[53] For these reasons, Filippa Lentzos notes that "it is not possible to verify the BWC with the same level of accuracy and reliability as the verification of nuclear treaties".[73]

Financial health of the Convention[]

BWC intersessional program meetings have recently been impeded by late payments and non-payments of financial contributions.[130] BWC States Parties agreed at the Meeting of States Parties in 2018, which was cut short due to funding shortfalls, on a package of remedial financial measures including the establishment of a Working Capital Fund.[130][131] This fund is financed by voluntary contributions and provides short-term financing in order to ensure the continuity of approved programs and activities.[131] Live information on the financial status of the BWC and other disarmament conventions is available publicly on the financial dashboard of the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs.[132]

See also[]

Biological weapons and warfare[]

- Australia Group of countries controlling exports to prevent the spread of biological and chemical weapons

- Biological weapons

- Biological warfare

- Biological terrorism

- Geneva Protocol, the first treaty to prohibit the use of biological and chemical weapons

- United Nations Security Council Resolution 1540, resolution to curb the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, particularly to non-state actors

Treaties for other types of weapons of mass destruction[]

- Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) (states parties)

- Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) (states parties)

- Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) (states parties)

- Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) (states parties)

References[]

- ^ Article XIV, Biological Weapons Convention.

- ^ "Status of the Biological Weapons Convention". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ Biological Weapons Convention, Article XIV.

- ^ Biological Weapons Convention, Article XV.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Biological Weapons Convention – UNODA". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Archived from the original on 15 February 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Article XIII, Biological Weapons Convention. Treaty Database, United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Disarmament Treaties Database: Biological Weapons Convention". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Report on universalization activities, 2019 Meeting of States Parties to the Biological Weapons Convention, BWC/MSP/2019/3. Geneva, 8 October 2019.

- ^ Cross, Glenn; Klotz, Lynn (3 July 2020). "Twenty-first century perspectives on the Biological Weapon Convention: Continued relevance or toothless paper tiger". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 76 (4): 185–191. Bibcode:2020BuAtS..76d.185C. doi:10.1080/00963402.2020.1778365. ISSN 0096-3402. S2CID 221061960.

- ^ Preamble, Biological Weapons Convention. Treaty Database, United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Feakes, D. (August 2017). "The Biological Weapons Convention". Revue Scientifique et Technique (International Office of Epizootics). 36 (2): 621–628. doi:10.20506/rst.36.2.2679. ISSN 0253-1933. PMID 30152458.

- ^ Gerstein, Daniel (2013). National Security and arms control in the age of biotechnology: the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-4422-2312-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Tucker, Jonathan (1 August 2001). "Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) Compliance Protocol". Nuclear Threat Initiative. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Wheelis, Mark (2002). "Biological Warfare at the 1346 Siege of Caffa". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 8 (9): 971–975. doi:10.3201/eid0809.010536. PMC 2732530. PMID 12194776.

- ^ "Text of the 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ "Disarmament Treaties Database: 1925 Geneva Protocol". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Beard, Jack M. (April 2007). "The Shortcomings of Indeterminacy in Arms Control Regimes: The Case of the Biological Weapons Convention". American Journal of International Law. 101 (2): 277–284. doi:10.1017/S0002930000030098. ISSN 0002-9300. S2CID 8354600.

- ^ Guillemin, Jeanne (2005). Biological Weapons: From the Invention of State-sponsored Programs to Contemporary Bioterrorism. Columbia University Press.

- ^ Rimmington, Anthony (15 November 2018). Stalin's Secret Weapon: The Origins of Soviet Biological Warfare. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-092885-8.

- ^ Preston, Richard (9 March 1998). "THE BIOWEAPONEERS". pp. 52-65. The New Yorker.

- ^ "Deseret Test Center, Project SHAD, Shady Grove revised fact sheet". Archived from the original on December 25, 2013. Retrieved December 24, 2013.

- ^ The National Academies; The Center for Research Information, Inc. (2004). HEALTH EFFECTS OF PROJECT SHAD BIOLOGICAL AGENT: BACILLUS GLOBIGII, (Bacillus licheniformis), (Bacillus subtilis var. niger), (Bacillus atrophaeus) (PDF) (Report). Prepared for the National Academies. Contract No. IOM-2794-04-001. Retrieved 14 January 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Notes for Project SHAD presentation by Jack Alderson given to Institute of Medicine on April 19, 2012 for SHAD II study[permanent dead link]

- ^ Miller, Judith; Engelberg, Stephen; Broad, William J. (2002). Germs: Biological Weapons and America's Secret War. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780684871592.

- ^ Nixon, Richard. "Remarks Announcing Decisions on Chemical and Biological Defense Policies and Programs", via The American Presidency Project, November 25, 1969, accessed December 21, 2008.

- ^ Graham, Thomas. Disarmament Sketches: Three Decades of Arms Control and International Law, University of Washington Press, 2002, pp. 26-30, (ISBN 0-295-98212-8)

- ^ Cirincione, Joseph, et al. Deadly Arsenals, p. 212.

- ^ Cirincione, Joseph (2005). Deadly Arsenals: Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical Threats. Carnegie Endowment. p. 212. ISBN 9780870032882.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "History of the Biological Weapons Convention". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ United Kingdom (6 August 1968), Working Paper on Microbiological warfare, ENDC/231. Conference of the Eighteen-Nation Committee on Disarmament.

- ^ Richard Nixon (1969), Statement on Chemical and Biological Defense Policies and Programs. Wikisource link.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Lentzos, Filippa (2019). "Compliance and Enforcement in the Biological Weapons Regime". WMDCE Series, United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research. 4: 3–4. doi:10.37559/WMD/19/WMDCE4.

- ^ Wright, Susan, ed. (16 November 2016). "Evolution of Biological Warfare Policy, 1945-1990". Preventing a Biological Arms Race. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-23148-0.

- ^ Goldblat, Jozef (June 1997). "The Biological Weapons Convention - An overview - ICRC". International Review of the Red Cross. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ "SUMMARY REPORT DUAL USE RESEARCH ON MICROBES: Biosafety, Biosecurity, Responsibility" (PDF). Volkswagen Foundation. 12 December 2014.

- ^ DAHLBURG, JOHN-THOR (15 September 1992). "Russia Admits It Violated Pact on Biological Warfare". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Alibek, Ken (1999). Biohazard: The Chilling True Story of the Largest Covert Biological Weapons Program in the World, Told from the Inside by the Man who Ran it. Delta. ISBN 0-385-33496-6.

- ^ Smithson, Amy (1999). "A bio nightmare". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 55 (4): 69–71. Bibcode:1999BuAtS..55d..69S. doi:10.2968/055004019.

- ^ Ainscough, Michael J. (2004). "Next Generation Bioweapons: Genetic Engineering and BW" (PDF). Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Koblentz, Gregory D.; Lentzos, Filippa (4 November 2016). "It's time to modernize the bioweapons convention". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

- ^ United Nations (1972). Biological Weapons Convention.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Biological Weapons Convention: An Introduction" (PDF). United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs: 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Implementation Support Unit (Geneva, 31 May 2016). Background information document: Additional understandings and agreements reached by previous Review Conferences relating to each article of the Convention, BWC/CONF.VIII/PC/4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Article I, Biological Weapons Convention. Wikisource.

- ^ Article II, Biological Weapons Convention. Wikisource.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Article III, Biological Weapons Convention. Wikisource.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Article IV, Biological Weapons Convention. Wikisource.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Article V, Biological Weapons Convention. Wikisource.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Article VI, Biological Weapons Convention. Wikisource.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Article VII, Biological Weapons Convention. Wikisource.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Article X, Biological Weapons Convention. Wikisource.

- ^ "Biological Weapons Convention". Wikisource. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k Rissanen, Jenni (1 March 2003). "Biological Weapons Convention". Nuclear Threat Initiative. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dando, Malcolm R. (2006). Bioterror and Biowarfare: A Beginner's Guide. Oneworld. p. 94. ISBN 9781851684472.

- ^ Article II, 1, Chemical Weapons Convention. Treaty Database, United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Final Document of the Third Review Conference of the States Parties to the Biological Weapons Convention, BWC/CONF.III/23. Geneva, 1991.

- ^ Lentzos, Filippa (1 May 2011). "Strengthening the Biological Weapons Convention confidence-building measures: Toward a cycle of engagement". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 67 (3): 26–33. Bibcode:2011BuAtS..67c..26L. doi:10.1177/0096340211406876. ISSN 0096-3402. S2CID 143444435.

- ^ United Nations General Assembly, Twenty-Fourth Session, 1969. 2603: Question of chemical and bacteriological (biological) weapons.

- ^ Johnson, Durward; Kraska, James (14 May 2020). "Some Synthetic Biology May Not be Covered by the Biological Weapons Convention". The Lawfare Institute.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Final Document of the Fourth Review Conference of the States Parties to the Biological Weapons Convention, BWC/CONF.IV/9. Geneva, 1996.

- ^ VERTIC (November 2016). Report on National Implementing Legislation, National Implementation Measures Programme, Biological Weapons Convention. London.

- ^ Drobysz, Sonia (5 February 2021). "Verification and implementation of the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention". The Nonproliferation Review: 1–11. doi:10.1080/10736700.2020.1823102. ISSN 1073-6700.

- ^ Dunworth, Treasa; Mathews, Robert J.; McCormack, Timothy L. H. (1 March 2006). "National Implementation of the Biological Weapons Convention". Journal of Conflict and Security Law. 11 (1): 93–118. doi:10.1093/jcsl/krl006. ISSN 1467-7954.

- ^ "National Implementation of the Biological Weapons Convention". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "BWC Legislation Database". VERTIC. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Coen, Bob; Nadler, Eric (2009). Dead Silence: Fear and Terror on the Anthrax Trail. Berkeley, California: Counterpoint. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-58243-509-1.

- ^ VERTIC (November 2016). Report on National Implementing Legislation, National Implementation Measures Programme, Biological Weapons Convention. London., p. 16

- ^ Biological Weapons Convention Implementation Support Unit (2018). "Background information, BWC/MSP/2018/MX.3/2". 2018 Meeting of Experts on Strengthening National Implementation of the States Parties to the Biological Weapons Convention.

- ^ Biological Weapons Convention Implementation Support Unit (2019). "Background information update, BWC/MSP/2019/MX.3/INF.2". 2019 Meeting of Experts on Strengthening National Implementation of the States Parties to the Biological Weapons Convention.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Final Document of the Second Review Conference of the States Parties to the Biological Weapons Convention, BWC/CONF.II/13. Geneva, 1986.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Report of the Formal Consultative Meeting, BWC/CONS/1". Formal Consultative Meeting to the States Parties of the Biological Weapons Convention. 1997.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "The Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) At A Glance". Arms Control Association. March 2020. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lentzos, Filippa (2019). "Compliance and Enforcement in the Biological Weapons Regime". WMDCE Series, United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research. Geneva, Switzerland. 4: 7–8. doi:10.37559/WMD/19/WMDCE4.

- ^ Biological Weapons Convention Implementation Support Unit (2018). "Background information document on assistance, response and preparedness, BWC/MSP/2018/MX.4/2". Meeting of Experts on Assistance, Response and Preparedness of the States Parties to the Biological Weapons Convention.

- ^ "Assistance and Cooperation Database". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Disarmament Treaties Database: Chemical Weapons Convention". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ "Disarmament Treaties Database: Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT)". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Achieving Universality". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Electronic Confidence-Building Measures Portal". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Confidence-Building Measures". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Lentzos, Filippa (2019). "Compliance and Enforcement in the Biological Weapons Regime". WMDCE Series, United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research. Geneva, Switzerland. 4: 11–12. doi:10.37559/WMD/19/WMDCE4.

- ^ Biological Weapons Convention Implementation Support Unit (2016). Background document: History and operation of the confidence-building measures, BWC/CONF.VIII/PC/3. Geneva: Eighth Review Conference of the States Parties to the Biological Weapons Convention.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Final Document of the First Review Conference of the States Parties to the Biological Weapons Convention, BWC/CONF.I/10. Geneva, 1980.

- ^ Duncan, Annabelle, and Robert J. Mathews. 1996. "Development of a Verification Protocol for the Biological Weapons Convention", in Poole, J.B. and R. Guthrie (eds). Verification 1996: Arms Control, Peacekeeping and the Environment. pp. 151–170. VERTIC.

- ^ VEREX (1993). Final report, BWC/CONF.III/VEREX/9. Geneva. Archived.

- ^ Special Conference of the States Parties to the Biological Weapons Convention (September 1994). Final Report, BWC/SPCONF/1. Geneva.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ad Hoc Group (April 2001). Protocol to the Biological Weapons Convention, BWC/AD HOC GROUP/CRP.8.

- ^ Dando, Malcolm (2006). Chapter 9: The Failure of Arms Control, In Bioterror and Biowarfare: A Beginner's Guide. Oneworld. ISBN 9781851684472.

- ^ Mahley, Donald (25 July 2001). "Statement of the United States to the Ad Hoc Group of Biological Weapons Convention States Parties".

- ^ Slevin, Peter (19 September 2002). "U.S. Drops Bid to Strengthen Germ Warfare Accord". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chairperson of the 2019 Meeting of Experts on Institutional Strengthening of the Convention (Geneva, 4 October 2019). Summary Report, BWC/MSP/2019/MX.5/2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Leitenberg, M.; Zilinskas, R. (2012). Conclusion. In The Soviet Biological Weapons Program. London: Harvard University Press. pp. 698–712. ISBN 9780674047709. JSTOR j.ctt2jbscf.30.

- ^ Leitenberg, M.; Zilinskas, R. (2012). Chapter 2: Beginnings of the "Modern" Soviet BW program, 1970–1977. In The Soviet Biological Weapons Program. London: Harvard University Press. pp. 51–78. ISBN 9780674047709. JSTOR j.ctt2jbscf.7.

- ^ Leitenberg, M.; Zilinskas, R. (2012). Chapter 15: Sverdlovsk 1979: The Release of Bacillus anthracis Spores from a Soviet Ministry of Defense Facility and Its Consequences. In The Soviet Biological Weapons Program. London: Harvard University Press. pp. 423–449. ISBN 9780674047709. JSTOR j.ctt2jbscf.21.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Meselson, M.; Guillemin, J.; Hugh-Jones, M.; Langmuir, A.; Popova, I.; Shelokov, A.; Yampolskaya, O. (18 November 1994). "The Sverdlovsk anthrax outbreak of 1979". Science. 266 (5188): 1202–1208. Bibcode:1994Sci...266.1202M. doi:10.1126/science.7973702. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 7973702.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Alibek, Ken (1999). Chapter 7: Accident at Sverdlovsk. In Biohazard: The Chilling True Story of the Largest Covert Biological Weapons Program in the World - Told from Inside by the Man Who Ran It. Delta. ISBN 0-385-33496-6.

- ^ Guillemin, Jeanne (1999). Anthrax: The Investigation of a Deadly Outbreak. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520229174.

- ^ "Yeltsin rewrites history on 1979 anthrax epidemic". Tampa Bay Times. 11 October 2005. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kelly, David (2002). "The Trilateral Agreement: lessons for biological weapons verification. David Kelly" (PDF). VERTIC Yearbook 2002: 93–110.

- ^ Zilinskas, Raymond A. (6 August 1997). "Iraq's Biological Weapons: The Past as Future?". JAMA. 278 (5): 418–424. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03550050080037. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 9244334.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dando, Malcolm (2006). Biological warfare 1972–2004. In Bioterror and Biowarfare: A Beginner's Guide. Oneworld. pp. 51–53. ISBN 9781851684472.

- ^ Leitenberg, Milton (1997). "Biological Weapons, International Sanctions and Proliferation". Asian Perspective. 21 (3): 7–39. ISSN 0258-9184. JSTOR 42704143.

- ^ Comprehensive Report of the Special Advisor to the DCI on Iraq’s WMD, with Addendums (Duelfer Report). Volume 3-Biological Warfare. (Washington, D.C., September 2004). Archived.

- ^ "Cuba BW allegations" (PDF). VERTIC Trust & Verify. 77. September 1997. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Adherence to and Compliance With Arms Control, Nonproliferation, and Disarmament Agreements and Commitments (PDF). U.S. Department of State. 2019. pp. 45–50. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 August 2019.

- ^ Isachenkov, Vladimir (4 October 2018). "Russia claims US running secret bio weapons lab in Georgia". AP NEWS. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ "Comment by the Information and Press Department on the Georgian Foreign Ministry's response apropos of the Richard Lugar Centre for Public Health Research". The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation. 27 May 2020. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Adherence to and Compliance With Arms Control, Nonproliferation, and Disarmament Agreements and Commitments (PDF). U.S. Department of State. 2019. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 August 2019.

- ^ Lentzos, Filippa (19 November 2018). "The Russian disinformation attack that poses a biological danger". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Roffey, Roger; Tunemalm, Anna-Karin (2 October 2017). "Biological Weapons Allegations: A Russian Propaganda Tool to Negatively Implicate the United States". The Journal of Slavic Military Studies. 30 (4): 521–542. doi:10.1080/13518046.2017.1377010. ISSN 1351-8046. S2CID 148825395.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Implementation Support Unit". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Final Document of the Sixth Review Conference of the States Parties to the Biological Weapons Convention, BWC/CONF.VI/6. Geneva, 2006.

- ^ Ord, Toby (2020). Chapter 2: Existential Risk. In The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity. Hachette Book Group. ISBN 978-1526600219.

- ^ "Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW)". Nuclear Threat Initiative. 30 October 2020. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ "Staff". International Atomic Energy Agency. 16 May 2014. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Annual Report 2018 (PDF). CTBTO Preparatory Commission. 2018. p. 62. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Meetings under the Biological Weapons Convention". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Article XII, Biological Weapons Convention. Wikisource.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Final Document of the Fifth Review Conference of the States Parties to the Biological Weapons Convention, BWC/CONF.V/17. Geneva, 2002.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Final Document of the Seventh Review Conference of the States Parties to the Biological Weapons Convention, BWC/CONF.VII/7. Geneva, 2011.

- ^ "BWC Article X Assistance and Cooperation Database". bwc-articlex.unog.ch. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ "BWC Sponsorship Programme – UNODA". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Final Document of the Eighth Review Conference of the States Parties to the Biological Weapons Convention, BWC/CONF.VIII/4. Geneva, 2016.

- ^ Meetings under the Biological Weapons Convention, [1]. Geneva, 2016.

- ^ "The Biological Weapons Convention: An Introduction" (PDF). United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs: 22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Brockmann, Kolja; Boulanin, Vincent; Bauer, Sibylle (2019). "BIO PLUS X: Arms Control and the Convergence of Biology and Emerging Technologies" (PDF). Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2021.

- ^ Lentzos, Filippa (1 November 2020). "How to protect the world from ultra-targeted biological weapons". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 76 (6): 302–308. Bibcode:2020BuAtS..76f.302L. doi:10.1080/00963402.2020.1846412. ISSN 0096-3402.

- ^ Future, Commission on a Global Health Risk Framework for the; National Academy of Medicine, Secretariat (16 May 2016). Accelerating Research and Development to Counter the Threat of Infectious Diseases. National Academies Press (US).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lentzos, Filippa (1 November 2011). "Hard to Prove: The Verification Quandary of the Biological Weapons Convention". The Nonproliferation Review. 18 (3): 571–582. doi:10.1080/10736700.2011.618662. ISSN 1073-6700. S2CID 143228489.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mackby, Jenifer (January 2019). "BWC Meeting Stumbles Over Money, Politics". Arms Control Association. Archived from the original on 16 February 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Report of the 2018 Meeting of States Parties, BWC/MSP/2018/6. Geneva, 11 December 2018.

- ^ "Financial Dashboard". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

External links[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Official resources created by the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs

- Official website of the Biological Weapons Convention

- Full text of the Biological Weapons Convention, Treaty Database

- Brochure: The Biological Weapons Convention: An Introduction

- Meetings Place. A page with details on disarmament meetings, including documents and presentations.

- Electronic Confidence-Building Measures facility

- Article X cooperation and assistance database

- External resources

- Arms control treaties

- Biological warfare

- Cold War treaties

- Human rights instruments

- Non-proliferation treaties

- Treaties of the Soviet Union

- Treaties concluded in 1972

- Treaties entered into force in 1975

- 1975 in politics

- Treaties of the Republic of Afghanistan

- Treaties of Albania

- Treaties of Algeria

- Treaties of Andorra

- Treaties of Angola

- Treaties of Antigua and Barbuda

- Treaties of Argentina

- Treaties of Armenia

- Treaties of Australia

- Treaties of Austria

- Treaties of Azerbaijan

- Treaties of the Bahamas

- Treaties of Bahrain

- Treaties of Bangladesh

- Treaties of Barbados

- Treaties of the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic

- Treaties of Belgium

- Treaties of Belize

- Treaties of the Republic of Dahomey

- Treaties of Bhutan

- Treaties of Bolivia

- Treaties of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Treaties of Botswana

- Treaties of the military dictatorship in Brazil

- Treaties of Brunei

- Treaties of the People's Republic of Bulgaria

- Treaties of Burkina Faso

- Treaties of Myanmar

- Treaties of Burundi

- Treaties of the People's Republic of Kampuchea

- Treaties of Cameroon

- Treaties of Canada

- Treaties of Cape Verde

- Treaties of Chile

- Treaties of the People's Republic of China

- Treaties of Taiwan

- Treaties of Colombia

- Treaties of the Republic of the Congo

- Treaties of Zaire

- Treaties of the Cook Islands

- Treaties of Costa Rica

- Treaties of Croatia

- Treaties of Cuba

- Treaties of Cyprus

- Treaties of Czechoslovakia

- Treaties of the Czech Republic

- Treaties of Denmark

- Treaties of Dominica

- Treaties of the Dominican Republic

- Treaties of Ecuador

- Treaties of El Salvador

- Treaties of Equatorial Guinea

- Treaties of Estonia

- Treaties of the Derg

- Treaties of Fiji

- Treaties of Finland

- Treaties of France

- Treaties of Gabon

- Treaties of the Gambia

- Treaties of Georgia (country)

- Treaties of West Germany

- Treaties of East Germany

- Treaties of Ghana

- Treaties of Greece

- Treaties of Grenada

- Treaties of Guatemala

- Treaties of Guinea-Bissau

- Treaties of Guyana

- Treaties of the Holy See

- Treaties of Honduras

- Treaties of the Hungarian People's Republic

- Treaties of Iceland

- Treaties of India

- Treaties of Indonesia

- Treaties of Pahlavi Iran

- Treaties of Ba'athist Iraq

- Treaties of Ireland

- Treaties of Italy

- Treaties of Ivory Coast

- Treaties of Jamaica

- Treaties of Japan

- Treaties of Jordan

- Treaties of Kazakhstan

- Treaties of Kenya

- Treaties of Kuwait

- Treaties of Kyrgyzstan

- Treaties of Laos

- Treaties of Latvia

- Treaties of Lebanon

- Treaties of Lesotho

- Treaties of Liberia

- Treaties of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya

- Treaties of Liechtenstein

- Treaties of Lithuania

- Treaties of Luxembourg

- Treaties of North Macedonia

- Treaties of Madagascar

- Treaties of Malawi

- Treaties of Malaysia

- Treaties of the Maldives

- Treaties of Mali

- Treaties of Malta

- Treaties of the Marshall Islands

- Treaties of Mauritania

- Treaties of Mauritius

- Treaties of Mexico

- Treaties of Moldova

- Treaties of Monaco

- Treaties of the Mongolian People's Republic

- Treaties of Montenegro

- Treaties of Morocco

- Treaties of Mozambique

- Treaties of Nauru

- Treaties of Nepal

- Treaties of the Netherlands

- Treaties of New Zealand

- Treaties of Nicaragua

- Treaties of Nigeria

- Treaties of Niger

- Treaties of North Korea

- Treaties of Norway

- Treaties of Oman

- Treaties of Pakistan

- Treaties of Palau

- Treaties of Panama

- Treaties of Papua New Guinea

- Treaties of Paraguay

- Treaties of Peru

- Treaties of the Philippines

- Treaties of the Polish People's Republic

- Treaties of Portugal

- Treaties of Qatar

- Treaties of the Socialist Republic of Romania

- Treaties of Rwanda

- Treaties of Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Treaties of Saint Lucia

- Treaties of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

- Treaties of San Marino

- Treaties of São Tomé and Príncipe

- Treaties of Saudi Arabia

- Treaties of Senegal

- Treaties of Yugoslavia

- Treaties of Seychelles

- Treaties of Sierra Leone

- Treaties of Singapore

- Treaties of Slovakia

- Treaties of Slovenia

- Treaties of the Solomon Islands

- Treaties of South Africa

- Treaties of South Korea

- Treaties of Spain

- Treaties of Sri Lanka

- Treaties of the Republic of the Sudan (1985–2011)

- Treaties of Suriname

- Treaties of Eswatini

- Treaties of Sweden

- Treaties of Switzerland

- Treaties of Tajikistan

- Treaties of Thailand

- Treaties of East Timor

- Treaties of Togo

- Treaties of Tonga

- Treaties of Trinidad and Tobago

- Treaties of Tunisia

- Treaties of Turkey

- Treaties of Turkmenistan

- Treaties of Uganda

- Treaties of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic

- Treaties of the United Arab Emirates

- Treaties of the United Kingdom

- Treaties of the United States

- Treaties of Uruguay

- Treaties of Uzbekistan

- Treaties of Vanuatu

- Treaties of Venezuela

- Treaties of Vietnam

- Treaties of the Yemen Arab Republic

- Treaties of South Yemen

- Treaties of Zambia

- Treaties of Zimbabwe

- Treaties extended to Greenland

- Treaties extended to the Faroe Islands

- Treaties extended to the Netherlands Antilles

- Treaties extended to Aruba

- Treaties extended to Saint Christopher-Nevis-Anguilla

- Treaties extended to Bermuda

- Treaties extended to the British Virgin Islands

- Treaties extended to the Cayman Islands

- Treaties extended to the Falkland Islands

- Treaties extended to Gibraltar

- Treaties extended to Montserrat

- Treaties extended to the Pitcairn Islands

- Treaties extended to Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha

- Treaties extended to South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

- Treaties extended to the Turks and Caicos Islands