Cage (organisation)

This article needs to be updated. (November 2016) |

| |

| Formation | October 2003 |

|---|---|

| Type | Advocacy organisation with a focus on Muslim detainees |

| Purpose | To raise awareness of the plight of the detainees held as part of the War on Terror and to "empower communities impacted by the War on Terror" |

| Headquarters | London, England |

Director | Adnan Siddiqui[1] |

| Website | www |

Formerly called | Cageprisoners |

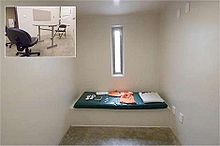

Cage is a London-based advocacy organisation which aims "to empower communities impacted by the War on Terror". The organisation says it "highlights and campaigns against state policies, developed as part of the War on Terror, striving for a world free from oppression and injustice".[2][3] The organisation was formed to raise awareness of the plight of the detainees held at Guantánamo Bay and elsewhere and has worked closely with former detainees held by the United States and campaigns on behalf of current detainees held without trial.[2][4][5] Cage was formerly Cageprisoners Ltd, and is sometimes styled as "CAGE".

Its outreach director, Moazzam Begg, is a former Guantánamo Bay detainee who was released without charge in 2005.

Aims[]

Cage is an advocacy organisation whose stated aim is "to empower communities impacted by the War on Terror". The organisation says it "highlights and campaigns against state policies, developed as part of the War on Terror, striving for a world free from oppression and injustice".[2] It has run campaigns in support of freeing all detainees who continue to be held without charges,[6] and to help former detainees to re-integrate into society.[7] Cage has also criticised the UK's anti-terrorism laws.[8]

Background[]

Cage's website was launched in October 2003.[9] It published names, photos and other information about detainees which the United States had kept secret, much of which was obtained from detainees' families.[10]

Cage's outreach director, Moazzam Begg, is a Briton from Birmingham who was held for three years by the United States government in extrajudicial detention as a suspected enemy combatant at Bagram in Afghanistan, and the Guantánamo Bay detainment camp in Cuba.[4][11] He was released without charge in 2005.[12] He has worked to represent detainees still held at Guantánamo, as well as to help former detainees become re-integrated into society. He has also been working with governments to persuade them to accept non-national former detainees, some of whom have been refused entry by their countries of origin.

Qur'an Desecration Report[]

In May 2005, Cage released The Qur'an Desecration Report, which contained accounts from former Bagram and Guantánamo prisoners who said they had suffered "systematic" religious abuse, including desecration of the Qur'an.[13]

Controversies and criticisms[]

Anwar al-Awlaki[]

After Anwar al-Awlaki's release from Yemeni detention in 2007, Begg was the first person to interview him.[14] Cage invited the cleric to address their Ramadan fundraising dinners in August 2008 (at Wandsworth Civic Centre, South London, by videolink, as he was banned from entering the UK) and August 2009 at Kensington Town Hall.[4][15]

Cage was criticised by the activist journalist Gita Sahgal for having a relationship with al-Awlaki, which she said "should have rung alarm bells", because he had been linked to al-Qaeda and various terrorists.[16] In November 2010, Cage issued a press release to clarify their position on al-Awlaki.[17] They noted that, before his 18-month detention, al-Awlaki had been known as a cleric of moderate views. In that period, he had been invited to speak at the Pentagon and had served as a chaplain at an American university. They defended their support of him as a prisoner held by Yemen without charge for 18 months, and said that at their events he had only spoken of his experiences as a former prisoner. Furthermore, they added that they strongly opposed his newly-espoused radical positions, but at the same time, they opposed the United States' plan to target him for assassination in a missile strike.[18] Awlaki was killed by the US in a 2011 drone strike.[19]

Amnesty International controversy[]

In February 2010, Amnesty International suspended Gita Sahgal, its gender unit head, after she criticised Amnesty for its links with Begg. She said it was "a gross error of judgment" to work with "Britain's most famous supporter of the Taliban".[20][21][22] Novelist-essayist Salman Rushdie supported her, saying: "Amnesty ... has done its reputation incalculable damage by allying itself with Moazzam Begg and his group Cageprisoners, and holding them up as human rights advocates".[23] The journalist Nick Cohen wrote in The Observer: "Amnesty ... thinks that liberals are free to form alliances with defenders of clerical fascists who want to do everything in their power to suppress liberals, most notably liberal-minded Muslims".[24]

Henry Jackson Society[]

After Osama bin Laden was killed in an American raid in May 2011, Cage published an editorial written as news satire. It announced "American War Criminal Barack Obama has been killed by Pakistani security forces in the UK".[25] Michael Weiss, a research director for the neoconservative Henry Jackson Society called the satire "a sick joke".[26]

Mohamed Emwazi ('Jihadi John')[]

In February 2015, Mohamed Emwazi, a 27-year-old Briton, was identified as the probable masked beheader of civilian captives of ISIS in Syria. Emwazi had, between 2009 and January 2012, been in contact with Cage while in the UK, complaining that he was being harassed by British intelligence agencies.[27][28] Following the naming, Cage's Press Officer, Cerie Bullivant, released a video detailing Cage's contact with Emwazi, saying "There is going to be pressure on Muslims to condemn and apologise ... we should not have to justify our humanity by running out and feeding into this idea that all Muslims are culpable for the actions of one person."[8][27]

At a press conference the following day, Cage's research director, Asim Qureshi, called Emwazi "a beautiful young man"[29] and "extremely kind, gentle and soft-spoken". In Qureshi's view, Emwazi's contact with the UK security services had contributed to his transformation into a killer, saying that, "Individuals are prevented from travelling, placed under house arrest and in the worst cases tortured, rendered or killed, seemingly on the whim of security agents".[30] Prime Minister David Cameron described the suggestion that Emwazi's radicalisation was the fault of British authorities as "reprehensible", whilst the then Mayor of London Boris Johnson called it an "apology for terror".[31] The Labour Member of Parliament (MP) John Spellar said that Cage were "very clearly coming out as apologists for terrorism".[32]

In the wake of the incident, the counter-extremist Quilliam Foundation questioned whether Cage could have done more to prevent Emwazi from travelling to Syria, saying "It's very, very important to uphold human rights in counter-extremism work, but for an organisation like Cage to focus entirely on grievances and allow those to be extrapolated in a radicalisation process is surely part of the problem and not part of the solution."[33] Qureshi's sympathies were questioned by Newsweek, after video footage emerged of his calling for support for "the jihad of our brothers and sisters" in Iraq and Afghanistan and other countries "facing the oppression of the West" at a 2006 Hizb ut-Tahrir rally.[34]

Following Emwazi's reported death in a drone strike in November 2015 in the Syrian Civil War, Cage was among those who expressed dissatisfaction that he had not been brought to trial.[35]

Partly as a result of Qureshi's statement, the Charity Commission pressured two charities that had previously funded Cage to cease doing so.[36] Amnesty International, which had previously campaigned with the organisation on issues relating to Guantánamo and torture, said, "We are reviewing whether any future association with the group would now be appropriate."[37]

Implementation of Sharia law[]

In an interview featured in Episode 5 of Julian Assange's World Tomorrow broadcast by RT on 15 May 2012, representatives of Cage Moazzam Begg and Asim Qureshi expressed support for the principle of creating an Islamic caliphate, including precise implementation of Sharia law.[38][non-primary source needed]

In a 2015 interview on the BBC's This Week, host Andrew Neil repeatedly asked Qureshi to clarify his position on Sharia law; Qureshi refused to condemn stoning-to-death for adultery.[39][40]

Other criticism[]

According to the BBC, "Human rights groups say they [Cage] are doing 'vital work' but critics have called the organisation 'apologists for terror'."[8]

Writing in The Daily Telegraph, Andrew Gilligan said Cage was a "terrorism advocacy group", and a propagator of a "myth of Muslim persecution". Gilligan also said that Liberty and Amnesty International treat Cage as a credible partner.[41]

The journalist Terry Glavin, writing in The National Post, described the organisation as "a front for Taliban enthusiasts and Al Qaida devotees that fraudulently presents itself as a human rights group".[42]

Muhammad Rabbani conviction[]

On 25 September 2017, Muhammad Rabbani, the international director of Cage, was found guilty at Westminster Magistrates Court of having wilfully obstructed police at Heathrow Airport by refusing to divulge the passwords to his mobile phone and laptop computer. Rabbani was given a conditional discharge for 12 months and ordered to pay £620 costs. Rabbani had been stopped whilst returning from Qatar, where Rabbani said he had interviewed a man to collect evidence for UK lawyers of that man's claims of having been tortured while in US custody. On two previous occasions Rabbani had refused to hand over passwords at ports and airports and had been allowed to pass.[43]

Gareth Peirce, Rabbani's solicitor, said the verdict would be challenged in the UK High Court. The verdict confirmed that UK police have the powers under Schedule 7 of the Terrorism Act 2000 to demand access to electronic devices. Rabbani claimed that he had been protecting the confidentiality of his client.[43] Rabbani and Cage described the conviction as a "moral victory" against Schedule 7.[44][45]

Charitable funding[]

Between 2007 and 2014, the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust gave grants to Cage totalling £271,250. In a similar period, the Roddick Foundation, founded by Anita Roddick, gave grants totalling £120,000. In 2015, following pressure from the UK government's Charity Commission, which had expressed concern that funding Cage risked damaging public confidence in charity, both entities agreed to cease funding Cage.[36] The Rowntree Trust defended its funding in a statement, commenting, "We believe (Cage) has played an important role in highlighting the ongoing abuses at Guantanamo Bay and at many other sites around the world, including many instances of torture".[32] Cage said that the majority of their income comes from private individuals and that the group "would continue its work regardless of the criticism levelled at it ... even though we aren't a proselytizing organisation, we are a Muslim response to a problem that largely affects Muslims".[32]

Lord Carlile, formerly the British Government's independent reviewer of anti-terrorism legislation, said at the time: "I have concerns about the group. There are civil liberty organisations which I do give money to but Cageprisoners is most certainly not one of them".[5]

In October 2015, following an application for judicial review by Cage, the Charity Commission changed its position and said it would not in future interfere in the discretion of charities to choose to fund Cage. The judicial review heard evidence that Theresa Villiers, a British Cabinet Minister, and US intelligence had both applied pressure on the charity commission to investigate Cage, with US intelligence agents describing Cage as a "jihadist front".[46]

Zakat[]

In 2014, Cage held an online discussion about Zakat (the Muslim religious obligation for charitable giving) and the Muslim obligation to prisoners. It appealed to Muslims to make donations to help free those unjustly imprisoned in Guantánamo and elsewhere.[47]

Libel case against The Times[]

In December 2020, Cage and Moazzam Begg received damages of £30,000 plus costs in a libel case they had brought against The Times newspaper. In June 2020, a report in The Times had suggested that Cage and Begg were supporting a man who had been arrested in relation to a knife attack in Reading in which three men were murdered. The Times report also suggested that Cage and Begg were excusing the actions of the accused man by mentioning mistakes made by the police and others. In addition to paying damages, The Times printed an apology. Cage stated that the damages amount would be used to "expose state-sponsored Islamophobia and those complicit with it in the press. ... The Murdoch press empire has actively supported xenophobic elements and undermined principles of open society and accountability. ... We will continue to shine a light on war criminals and torture apologists and press barons who fan the flames of hate".[48]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "Meet our team". Cage. Archived from the original on 26 November 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "About Us". Cage. Archived from the original on 25 November 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ "CAGE, Behind the headlines" (PDF). cage.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c O'Neill, Sean (4 January 2010). "Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab had links with London campaign group". The Times. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Mainstream charities have donated thousands to Islamic group fronted by terror suspect". The Telegraph. 1 March 2014. Archived from the original on 6 January 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ "About Us". Cage. Archived from the original on 5 August 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ MacAskill, Ewen (30 November 2010). "WikiLeaks cables show US U-turn over ex-Guantánamo inmate". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 7 February 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c McMicking, Henrietta (27 February 2015). "Cage: Important human rights group or apologists for terror?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ "Who we are". Cage. Archived from the original on 25 November 2016. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ^ "Names of the Detained in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba". The Washington Post. 15 March 2006. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010.

- ^ Ignatius, David (14 June 2006). "A Prison We Need to Escape". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ Tim Golden (15 June 2006). "Jihadist or Victim: Ex-Detainee Makes a Case". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010.

- ^ "Report into the Systematic and Institutionalised US Desecration of the Qur'an and other Islamic Rituals" (PDF). Cageprisoners. 16 May 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ "Moazzam Begg Interviews Imam Anwar Al Awlaki". Cageprisoners. 31 December 2007. Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ^ Sawer, Patrick, and Barrett, David, "Detroit bomber's mentor continues to influence British mosques and universities", The Telegraph, 2 January 2010, accessed 15 November 2016.

- ^ Gita Saghal (15 November 2010). "Human rights folly on Anwar al-Awlaki". Comment is free. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ "Press release: Cageprisoners and Anwar al-Awlaki – a factual background". Cage. 5 November 2010. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010.

- ^ "Top charities give £200,000 to group which supported al-Qaeda cleric". The Telegraph. 6 November 2010. Archived from the original on 27 September 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ "Two U.S.-Born Terrorists Killed in CIA-Led Drone Strike". Fox News. 30 September 2011. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011.

- ^ "How Amnesty chose the wrong poster-boy". The Times. 9 February 2010. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ^ "Gita Sahgal: A Statement". The Spectator. 7 February 2010. Archived from the original on 16 March 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ^ "Amnesty shouldn't support men like Moazzam Begg". The Independent. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ "Salman Rushdie's statement on Amnesty International". The Sunday Times. 21 February 2010. Archived from the original on 1 June 2010. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- ^ "We abhor torture – but that requires paying a price". The Guardian. 14 February 2010. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ "What If You Read This Headline? Breaking News – Barack Obama Is Dead". Cageprisoners. Information Clearing House. 9 May 2011. Archived from the original on 14 November 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ "'Barack Obama is dead': A sick joke from Moazzam Begg's Cageprisoners group". The Henry Jackson Society. 10 May 2011. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bullivant, Cerie (26 February 2015). "Cage & Mohammed Emwazi aka Jihadi John". Cage Press Officer. Archived from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ Ramesh, Randeep; Jalabi, Raya (3 March 2015). "Mohammed Emwazi tapes: '9/11 was wrong'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ "IS 'Jihadi John' suspect 'a beautiful young man' – Cage". BBC. 26 February 2015. Archived from the original on 30 May 2016. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "'Jihadi John' Used To Be 'Kind And Gentle'". Sky News. 27 February 2015. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ "Jihadi John: Activist who praised Mohammed Emwazi as "beautiful" caught on video backing jihad". The Telegraph. 27 February 2015. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Charities that funded Cage, one time supporter of IS's Emwazi, under pressure". Reuters. 4 March 2015. Archived from the original on 5 March 2015.

- ^ "What is Cage? Jihadi John confidant that describes executioner Mohammed Emwazi as 'beautiful'". International Business Times. 26 February 2015. Archived from the original on 28 February 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ "Jihadi John: UK Campaigner With Links to Emwazi Called for Jihad". Newsweek. 26 February 2015. Archived from the original on 28 February 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ "Jihadi John 'dead': Jeremy Corbyn says 'far better' if militant had been tried in court rather than killed". The Independent. 14 November 2015. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Charities sever ties with pressure group Cage over Mohammed Emwazi links". The Guardian. 6 March 2015. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ "Amnesty International considers cutting links with pressure group Cage". The Guardian. 2 March 2015. Archived from the original on 22 January 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ "Episode 5". wikileaks.org. Archived from the original on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ^ Rosa Prince (6 March 2015). "Cage director Asim Qureshi refuses to condemn stoning of adulterous women". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 18 November 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ Tom Porter (6 March 2015). "Cage director Asim Qureshi refuses to condemn stoning women or female genital mutilation". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 9 March 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ^ Gilligan, Andrew (28 February 2015). "Cage: the extremists peddling lies to British Muslims to turn them into supporters of terror". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 23 April 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ Glavin, Terry (8 February 2010). "Amnesty International doubles down on appeasement". The National Post.[dead link] Alt URL

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bowcott, Owen (25 September 2017). "Campaign group chief found guilty of refusing to divulge passwords Campaign group chief found guilty of refusing to divulge passwords". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ "Muhammad Rabbani: "we have won the moral argument"". Press release. Cage. 25 September 2017. Archived from the original on 27 November 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ "Rabbani Trial Reactions: A Moral Victory Against Schedule 7". Cage. 27 September 2017. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ Ramesh, Randeep (21 October 2015). "Charities can fund Cage campaign group, commission agrees". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ "Zakah and the forgotten Islamic obligation towards prisoners". Archived from the original on 19 March 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

This Ramadan, give your support to the cause of the oppressed by paying your zakah and sadaqah to CAGE. Any money we collect in Zakah is restricted to matters which directly benefit prisoners' cases

- ^ Sabin, Lamiat (4 December 2020). "The Times pays £30k damages over article defaming Muslim activists". Morning Star. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- Prison-related organizations

- Islam in the United Kingdom

- Advocacy groups in the United Kingdom

- 2003 establishments in the United Kingdom

- Organizations established in 2003

- War on Terror