Characteres generum plantarum

Characteres generum plantarum (complete title Characteres generum plantarum, quas in Itinere ad Insulas Maris Australis, Collegerunt, Descripserunt, Delinearunt, annis MDCCLXXII-MDCCLXXV Joannes Reinoldus Forster et Georgius Forster, "Characteristics of the types of plants collected, described, and delineated during a voyage to islands of the South Seas, in the years 1772–1775 by Johann Reinhold Forster and Georg Forster") is a 1775/1776 book by Johann Reinhold Forster and Georg Forster about the botanical discoveries they made during the second voyage of James Cook. The book, which contains 78 plates, introduced 94 binomial names from 75 genera, of which 43 are still the accepted names today.

Background[]

Johann Reinhold Forster was the main scientific companion travelling with James Cook on his 1772–1775 second voyage. His son Georg Forster accompanied him as draughtsman and assistant.[4] Botanical specimens were collected by Georg and Anders Sparrman,[5] a student of Carl Linnaeus who had been hired as assistant by Reinhold Forster.[4] After the return from the voyage, Characteres generum plantarum was the first scientific publication to come out.[6] Reinhold Forster tried to use it to enhance his own reputation as a scientist and to compete with the first voyage's botanist, Joseph Banks.[7] He was uneasy that Banks might already have described and published most of the species names and wanted to be able to claim the discovery of the species he found as his own achievement.[8]

Characteres was prepared during the voyage, written quickly and contained numerous errors. Reinhold Forster later regretted its rushed publication and not having consulted Banks for his opinions and access to his collections.[9][10] Cook unsuccessfully attempted to halt the book's publication in the autumn of 1775, possibly in order to prevent any preemption of his own narrative, but Lord Sandwich, the First Lord of the Admiralty, gave his permission for the book to be published at the Forster's own expense.[11] The first folio edition was presented to King George III in November 1775, probably on 17 November; this also effectively made it impossible for Sandwich to withdraw the permission for publication.[12]

Content[]

The book starts with an introduction that dedicates it to King George III, explains the context of the journey and describes the methods used and the contributions by Reinhold and Georg Forster as well as Sparrman. It also contains an apology for containing only 75 genera.[13][14] The book contains 78 plates depicting the plants. These are described by Dan Nicolson as "almost all of floral dissections at natural size, hence unappealing".[15]

The plants were named according to the Linnaean model. For some of them, local names or usage influenced the choice of names.[8] For example, Diospyros including Diospyros major were called Maba by the Forsters, referring to their Tongan name.[8][16][17] Xylosma were named Myroxylon ("myrrh tree"), referring to the inhabitants' use of it to scent coconut-based hair oil.[18][19] Many genera were named after friends or potential patrons, including Barringtonia, honouring Daines Barrington, and Pennantia, named after Thomas Pennant.[20]

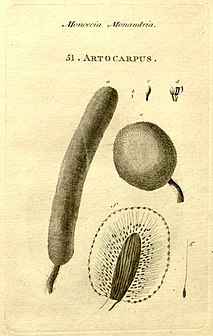

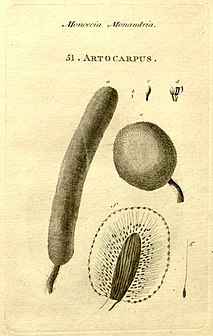

Plate 51 Artocarpus, the breadfruit genus, anatomical details of fruit

Plate 51.a Artocarpus, whole breadfruit

Editions, formats and owners[]

The book was printed in both folio and quarto formats, with the folios intended as presents for friends, supporters and potential patrons of the Forsters. The majority is dated 1776, with one quarto and two folios from 1775 known.[6] It is likely that both folio and quarto editions were printed in November 1775.[12] The two 1775 folios are the one presented to George III and one sent by Reinhold Forster to Linnaeus in November 1775.[21] According to a letter from Reinhold Forster, 25 folio copies were made,[20] of which at least 16 folios have been traced, including the copies of Joseph Banks, Thomas Pennant, and Nikolaus Joseph von Jacquin. The copy dedicated to Charles III of Spain is now in the library of the University of California, Los Angeles, while the current whereabouts of the one originally belonging to Anna Blackburne (which was offered for sale in 1944[22]) are unknown.[23] Of the quarto edition, at least 200, probably several hundred copies were printed, and it was published and widely available in January or February 1776, selling for £1 7s.[12]

The book was translated into German by Johann Simon von Kerner, head of the Botanical Gardens of Stuttgart, appearing in 1779.[24][25] The original Latin was reprinted in Volume 6 of Georg Forster's complete works, which were published by the German Academy of Sciences at Berlin and continued by the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities.[26][27]

Importance and controversy[]

The book is an important contribution to the botany of New Zealand, as the first publication containing names and descriptions of its native species. The earlier observations by Banks and Solander from the first voyage of James Cook were only published much later.[28] Of the 94 binomials from 75 genera in the book, 43 are the accepted names even today, and for seven others, the generic name is still used while the binomials are no longer the accepted names.[29]

William Wales, the astronomer on the voyage with Cook, stated he had "not been able to extract any information what ever, except that they found, in the whole 75 New Plants, but whether those are all, or any of them, different from such as had been discovered by Mr Banks, he cannot learn."[30][31] Later, Elmer Drew Merrill accused the Forsters both of pirating Solander's work in Characteres and of not using Solander's names;[32][33] however, there is no evidence that they had access to Solander's or Banks's manuscripts after the voyage.[34] Also, later botanists Dan Henry Nicolson and Francis Raymond Fosberg, who studied the botanical contributions of the Forsters to Cook's second voyage, note that the work was not plagiarised from Solander, but done during the expedition, as evidenced by Forster manuscripts from the voyage that Merrill was not aware of.[35]

References[]

Notes[]

- ^ a b National Portrait Gallery.

- ^ Mariss (2019), p. 166.

- ^ Beaglehole (1992), p. viii.

- ^ a b Rosove (2015), p. 611.

- ^ Nicolson & Fosberg (2004), p. 31.

- ^ a b Earp (2013).

- ^ Dawson (1973), pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b c Mariss (2019), p. 125.

- ^ Hoare (1976), p. 139.

- ^ Nicolson & Fosberg (2004), p. 19.

- ^ Hoare (1976), p. 140.

- ^ a b c Rosove (2015), p. 613.

- ^ Edgar (1969).

- ^ Hoare (1982), p. 82.

- ^ Nicolson (1998).

- ^ Forster & Forster (1776), pp. 121–122.

- ^ Nicolson & Fosberg (2004), pp. 389–391.

- ^ Forster & Forster (1776), pp. 125–126.

- ^ Nicolson & Fosberg (2004), pp. 452–454.

- ^ a b Gordon (1975), p. 201.

- ^ Rosove (2015), p. 615-616.

- ^ St. John (1971), pp. 567–568.

- ^ Rosove (2015), p. 615.

- ^ Forster & Forster (1779).

- ^ Dawson (1973), p. 11.

- ^ Forster (2003), pp. 9–23.

- ^ Uhlig (2013), p. 139.

- ^ Dawson (1998).

- ^ Nicolson & Fosberg (2004), p. 15.

- ^ Beaglehole (1969), pp. xl–xli.

- ^ Gordon (1975), p. 242.

- ^ Merrill (1954), pp. 205–206.

- ^ Nicolson & Fosberg (2004), p. 12.

- ^ Hoare (1982), p. 86.

- ^ Nicolson & Fosberg (2004), p. 51.

Bibliography[]

- Beaglehole, John C. (1969). The journals of Captain James Cook on his voyages of discovery. II. Cambridge: Published for the Hakluyt Society at the University Press. OCLC 1052665808.

- Beaglehole, J. C. (1 April 1992). The Life of Captain James Cook. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2009-0.

- Dawson, Ruth (1973). Georg Forster's Reise um die Welt. A Travelogue in its Eighteenth-Century Context (PhD thesis). University of Michigan. OCLC 65229601.

- Dawson, John (1998). "The Forsters, Father and Son, Naturalists on Cook's Second Voyage". New Zealand Slavonic Journal: 99–110. ISSN 0028-8683. JSTOR 40921981.

- Earp, C. (1 December 2013). "The date of publication of the Forsters' Characteres Generum Plantarum revisited". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 51 (4): 252–263. doi:10.1080/0028825X.2013.806935. ISSN 0028-825X. S2CID 85352282.

- Edgar, Elizabeth (1 December 1969). "Preface to "Characteres Generum Plantarum" by J. R. and G. Forster, 1776; a translation". New Zealand Journal of Botany. 7 (4): 311–315. doi:10.1080/0028825X.1969.10428847. ISSN 0028-825X.

- Forster, Georg (2003). Popp, Klaus-Georg (ed.). Schriften zur Naturkunde: Texte. Georg Forsters Werke. Vol. 6.1. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag. ISBN 3-05-002262-0. OCLC 615375337.

- Forster, Johann Reinhold; Forster, Georg (1776). Characteres generum plantarum, quas in itinere ad insulas maris Australis, collegerunt, descripserunt, delinearunt, annis 1772–1775 Joannes Reinoldus Forster et Georgius Forster (in Latin). Londini : Prostant apud B. White, T. Cadell, & P. Elmsly.

- Forster, Johann Reinhold; Forster, Georg (1779). Johann Reinhold Forster's, Doktor der Rechte; Mitglied der Königlichen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften, und der Antiq. zu London, und Georg Forster's, Beschreibungen der Gattungen von Pflanzen, auf einer Reise nach den Inseln der Süd-See : gesammelt, beschrieben und abgezeichnet während den Jahren 1772. bis 1775 (in German). Translated by Kerner, Johann Simon. Stuttgart.

- Gordon, Joseph Stuart (1975). Reinhold and Georg Forster in England, 1766–1780 (Thesis). Ann Arbor: Duke University. OCLC 732713365.

- Hoare, Michael Edward (1976). The Tactless Philosopher: Johann Reinhold Forster (1729–98). Hawthorne Press. ISBN 9780725601218.

- Hoare, Michael Edward (1982). The Resolution journal of Johann Reinhold Forster, 1772-1775. Hakluyt Society. ISBN 978-0-904180-10-7.

- Mariss, Anne (9 September 2019). Johann Reinhold Forster and the Making of Natural History on Cook's Second Voyage, 1772–1775. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4985-5615-6.

- Merrill, Elmer D (1954). The botany of Cook's voyages and its unexpected significance in relation to anthropology, biogeography, and history. Waltham, Mass.: Chronica Botanica Co. OCLC 647164110.

- National Portrait Gallery. "Portrait of Dr Johann Reinhold Forster and his son George Forster, c. 1780". National Portrait Gallery collection. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- Nicolson, Dan H. (1998). "First Taxonomic Assessment of George Forster's Botanical Artwork at Gotha (Thuringia, Germany)". Taxon. 47 (3): 581–592. doi:10.2307/1223579. ISSN 0040-0262. JSTOR 1223579.

- Nicolson, Dan H; Fosberg, F. Raymond (2004). The Forsters and the botany of the Second Cook Expedition (1772–1775). Ruggell, Liechtenstein; Königstein, Germany: A.R.G. Gantner Verlag ; Distributed by Koeltz Scientific Books. ISBN 978-3-906166-02-5. OCLC 55731186.

- Rosove, Michael H. (2015). "The folio issues of the Forsters' Characteres Generum Plantarum (1775 and 1776): a census of copies". Polar Record. 51 (6): 611–623. doi:10.1017/S0032247414000722. ISSN 0032-2474. S2CID 129922206.

- St. John, Harold (1971). "The date of publication of Forsters' Characteres generum plantarum and its relation to contemporary works". Le Naturaliste Canadien. 98 (3): 561–581.

- Uhlig, Ludwig (2013). "Der polyglotte Forster: Fremdsprachige Bekenntnisse im Zusammenhang seines Lebens" (PDF). Georg-Forster-Studien (in German). Kassel University Press. 20: 135–178.

External links[]

Data related to Characteres generum plantarum at Wikispecies

Data related to Characteres generum plantarum at Wikispecies

- 1775 books

- 1776 books

- Botany books

- 18th-century Latin books

- Books about New Zealand