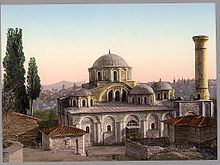

Chora Church

The Kariye Mosque (Turkish: Kariye Camii), or the Church of the Holy Saviour in Chora (Greek: Ἐκκλησία τοῦ Ἁγίου Σωτῆρος ἐν τῇ Χώρᾳ), is a medieval Greek Orthodox church[1] used as a mosque today in the Edirnekapı neighborhood of Istanbul, Turkey. The neighborhood is situated in the western part of the municipality (belediye) of the Fatih district. The Church of the Holy Saviour in Chora was built in the style of Byzantine architecture. In the 16th century, during the Ottoman era, the Christian church was converted into a mosque; it became a museum in 1945, and was turned back into a mosque in 2020 by President Erdogan[2][3] but the mosque reversion has been halted as of January 2021 due to lack of Islamic cultural significance and clerical interest, compared to the Hagia Sophia.[4] The interior of the building is covered with some of the oldest and finest surviving Byzantine Christian mosaics and frescoes; they were uncovered and restored after the building was secularized and turned into a museum.

Name[]

The original, 4th-century monastery containing the church, was outside Constantinople's city walls. Literally translated, the church's full name was the Church of the Holy Saviour in the Country (Greek ἡ Ἐκκλησία τοῦ Ἁγίου Σωτῆρος ἐν τῇ Χώρᾳ, hē Ekklēsia tou Hagiou Sōtēros en tēi Chōrāi). It is therefore sometimes incorrectly referred to as "Saint Saviour". However, "The Church of the Holy Redeemer in the Fields" would be a more natural rendering of the name in English. The last part of the Greek name, Chora, referring to its location originally outside of the walls, became the shortened name of the church. The name must have carried symbolic meaning, as the mosaics in the narthex describe Christ as the Land of the Living (ἡ Χώρα τῶν ζώντων, hē Chōra tōn zōntōn) and Mary, the Mother of Jesus, as the Container of the Uncontainable (ἡ Χώρα τοῦ Ἀχωρήτου, hē Chōra tou Achōrētou).

History[]

First phase (4th century)[]

The Chora Church was originally built in the early 4th century as part of a monastery complex outside the city walls of Constantinople erected by Constantine the Great, to the south of the Golden Horn. However, when Theodosius II built his formidable land walls in 413–414, the church became incorporated within the city's defences, but retained the name Chora (for the presumed symbolism of the name see above).

2nd phase (11th century)[]

The majority of the fabric of the current building dates from 1077–1081, when Maria Dukaina, the adoptive mother of Alexius I Comnenus, rebuilt the Chora Church as an inscribed cross or quincunx: a popular architectural style of the time. Early in the 12th century, the church suffered a partial collapse, perhaps due to an earthquake.

3rd phase: new decoration (14th century)[]

The church was rebuilt by Isaac Comnenus, Alexius's third son. However, it was only after the third phase of building, two centuries after, that the church as it stands today was completed. The powerful Byzantine statesman Theodore Metochites endowed the church with many of its fine mosaics and frescos. Theodore's impressive decoration of the interior was carried out between 1315 and 1321. The mosaic-work is the finest example of the Palaeologian Renaissance. The artists remain unknown. In 1328, Theodore was sent into exile by the usurper Andronicus III Palaeologus. However, he was allowed to return to the city two years later, and lived out the last two years of his life as a monk in his Chora Church.

Until the Fall of Constantinople[]

In the late 13th and early 14th centuries, the monastery was home to the scholar Maximus Planudes, who was responsible for the restoration and reintroduction of Ptolemy's Geography to the Byzantines and, ultimately, to Renaissance Italy. During the last siege of Constantinople in 1453, the Icon of the Theotokos Hodegetria, considered the protector of the City, was brought to Chora in order to assist the defenders against the assault of the Ottomans.[5]

Kariye Mosque (c. 1500–1945)[]

Around fifty years after the fall of the city to the Ottomans, Atık Ali Pasha, the Grand Vizier of Sultan Bayezid II, ordered the Chora Church to be converted into a mosque — Kariye Camii. The word Kariye derived from the Greek name Chora.[6] Due to the prohibition against iconic images in Islam, the mosaics and frescoes were covered behind a layer of plaster. This and frequent earthquakes in the region have taken their toll on the artwork.

Museum, art restoration (1945–2020)[]

In 1945, the building was designated a museum by the Turkish government.[7] In 1948, Americans Thomas Whittemore and Paul A. Underwood, from the Byzantine Institute of America and the Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies, sponsored a restoration program. From that time on, the building ceased to be a functioning mosque. In 1958, it was opened to the public as a museum — Kariye Müzesi.

Reconversion to a mosque (2020–)[]

In 2005, the Association of Permanent Foundations and Service to Historical Artifacts and Environment filed a lawsuit to challenge the status of the Chora Church as a museum.[8] In November 2019, the Turkish Council of State, Turkey's highest administrative court, ordered that it was to be reconverted to a mosque.[7] In August 2020, its status changed to a mosque.[9]

The move to convert Chora Church into a mosque was condemned by the Greek Foreign Ministry, Greek Orthodox and Protestant Christians.[2] This caused a sharp rebuke by Turkey.[10]

On Friday 30 October 2020, Muslim prayers were held for the first time after 72 years.[11]

Interior[]

The Chora Church is not as large as some of the other surviving Byzantine churches of Istanbul (it covers 742.5 m²) but it is unique among them, because of its almost completely still extant internal decoration. The building divides into three main areas: the entrance hall or narthex, the main body of the church or naos (nave), and the side chapel or parecclesion. The building has six domes: two above the esonarthex, one above the parecclesion and three above the naos.

Narthex[]

The main, west door of the Chora Church opens into the narthex. It divides north-south into the outer, or exonarthex and the inner, or esonarthex.

Outer narthex (exonarthex)[]

The exonarthex (or outer narthex) is the first part of the church that one enters. It is a transverse corridor, 4 m wide and 23 m long, which is partially open on its eastern length into the parallel esonarthex. The southern end of the exonarthex opens out through the esonarthex forming a western ante-chamber to the parecclesion. The mosaics that decorate the exonarthex include:

- Joseph's dream and journey to Bethlehem;

- Enrollment for taxation;

- Nativity, birth of Christ;

- Journey of the Magi;

- Inquiry of King Herod;

- Flight into Egypt;

- Two frescoes of the massacres ordered by King Herod;

- Mothers mourning for their children;

- Flight of Elizabeth, mother of John the Baptist;

- Joseph dreaming, return of the holy family from Egypt to Nazareth;

- Christ taken to Jerusalem for the Passover;

- John the Baptist bearing witness to Christ;

- Miracle;

- Three more Miracles.

- Jesus Christ;

- Virgin and Angels praying.

Inner narthex (esonarthex)[]

The esonarthex (or inner narthex) is similar to the exonarthex, running parallel to it. Like the exonarthex, the esonarthex is 4 m wide, but it is slightly shorter, 18 m long. Its central, eastern door opens into the naos, whilst another door, at the southern end of the esonarthex opens into the rectangular ante-chamber of the parecclesion. At its northern end, a door from the esonarthex leads into a broad west-east corridor that runs along the northern side of the naos and into the prothesis. The esonarthex has two domes. The smaller is above the entrance to the northern corridor; the larger is midway between the entrances into the naos and the pareclession.

- Enthroned Christ with Theodore Metochites presenting a model of his church;

- Saint Peter;

- Saint Paul;

- Deesis, Christ and the Virgin Mary (without John the Baptist) with two donors below;

- Genealogy of Christ;

- Religious and noble ancestors of Christ.

The mosaics in the first three bays of the inner narthex give an account of the Life of the Virgin, and her parents. Some of them are as follows:

- Rejection of Joachim's offerings;

- Annunciation of Saint Anne, the angel of the Lord announcing to Anne that her prayer for a child has been heard;

- Meeting of Joachim and Anne;

- Birth of the Virgin Mary;

- First seven steps of the Virgin;

- The Virgin given affection by her parents;

- The Virgin blessed by the priests;

- Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple;

- The Virgin receiving bread from an Angel;

- The Virgin receiving the skein of purple wool, as the priests decided to have the attendant maidens weave a veil for the Temple;

- Zechariah praying, when it was time for the Virgin to marry, High Priest Zechariah called all the widowers together and placed their rods on the altar, praying for a sign showing to whom she should be given;

- The Virgin entrusted to Joseph;

- Joseph taking the Virgin to his house;

- Annunciation to the Virgin at the well;

- Joseph leaving the Virgin, Joseph had to leave for six months on business and when he returned the Virgin was pregnant and he is suspicious of that.

[]

The central doors of the esonarthex lead into the main body of the church, the naos. The largest dome in the church (7.7 m diameter) is above the centre of the naos. Two smaller domes flank the modest apse: the northern dome is over the prothesis, which is linked by short passage to the bema; the southern dome is over the diaconicon, which is reached via the parecclesion.

Naos view towards apse

Christ

Mary and child

Mary and child detail

Dormition Position above door

Dormition of Mary total

Dormition central part

Dormition Mary

Dormition Mary in "sleep"

- Koimesis, the Dormition of the Virgin. Before ascending to Heaven, her last sleep. Jesus is holding an infant, symbol of Mary's soul;

- Jesus Christ;

- Theodokos, the Virgin Mary with child.

Side chapel (parecclesion)[]

To the right of the esonarthex, doors open into the side chapel, or parecclesion. The parecclesion was used as a mortuary chapel for family burials and memorials. The second largest dome (4.5 m diameter) in the church graces the centre of the roof of the parecclesion. A small passageway links the parecclesion directly into the naos, and off this passage can be found a small oratory and a storeroom. The parecclesion is covered in frescoes:

- Anastasis, the Resurrection. Christ, who had just broken down the gates of hell, is standing in the middle and pulling Adam and Eve out of their tombs. Behind Adam stand John the Baptist, David, and Solomon. Others are righteous kings;

- Second coming of Christ, the last judgment. Jesus is enthroned and on both sides the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist (this trio is also called the Deesis);

- Virgin and Child;

- Heavenly Court of Angels;

- Two panels of Moses.

The Anastasis fresco in the parecclesion of the Chora Church.

The Virgin and child, painted dome of the parecclesion of Chora Church.

Close-up of the Virgin Mother with child, dome of the parecclesion

See also[]

- Icon of the Hodegetria

- Monastery of the Panaghia Hodegetria

- Church of the Virgin Pammakaristos

- History of Roman and Byzantine domes

Notes[]

- ^ Ousterhout 1988.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Casper, Jayson (21 August 2020). "Turkey Turns Another Historic Church into a Mosque". Christianity Today. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ "Turkey converts Kariye Museum into mosque". Hürriyet Daily News. 21 August 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/has-turkey-halted-plans-to-turn-museum-into-a-mosque

- ^ Van Millingen

- ^ "About Chora". choramuseum.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Yackley, Ayla (3 December 2019). "Court Ruling Converting Turkish Museum to Mosque Could Set Precedent for Hagia Sophia". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ Kokkinidis, Tassos. "Turkey to Turn Historic Orthodox Church Into a Mosque; Is Hagia Sophia Next?". Greek Reporter. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ "Turkey converts Kariye Museum into mosque". Hürriyet Daily News website. 21 August 2020. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ^ "Turkey slams Greece over statement on conversion of Kariye Museum to mosque". Hürriyet Daily News website. 22 August 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ Istanbul’s Chora to open as mosque for Muslim prayers on Oct. 30

References[]

- Van Millingen, Alexander (1912). Byzantine Churches in Constantinople. London: MacMillan & Co.

- Ousterhout, Robert (2002). The Art of the Kariye Camii. London-Istanbul: Scala. ISBN 975-6899-76-X.

Literature[]

- Chora: The Kariye Museum. Net Turistik Yayınlar (1987). ISBN 978-975-479-045-0

- Feridun Dirimtekin. The historical monument of Kariye. Türkiye Turing ve Otomobil Kurumu (1966). ASIN B0007JHABQ

- Semavi Eyice. Kariye Mosque Church of Chora Monastery. Net Turistik Yayınlar A.Ş. (1997). ISBN 978-975-479-444-1

- Çelik Gülersoy. Kariye (Chora). ASIN B000RMMHZ2

- Jonathan Harris, Constantinople: Capital of Byzantium. Hambledon/Continuum (2007). ISBN 978-1-84725-179-4

- Karahan, Anne. Byzantine Holy Images – Transcendence and Immanence. The Theological Background of the Iconography and Aesthetics of the Chora Church (monography, 355 pp) (Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta No. 176) Leuven-Paris-Walpole, MA: Peeters Publishers 2010.ISBN 978-90-429-2080-4

- Karahan, Anne. “The Paleologan Iconography of the Chora Church and its Relation to Greek Antiquity”. In: Journal of Art History 66 (1997), Issue 2 & 3: pp. 89–95 Routhledge (Taylor & Francis Group online publication 1 September 2008: DOI:10.1080/00233609708604425) 1997

- Krannert Art Museum. Restoring Byzantium: The Kariye Camii in Istanbul and the Byzantine Institute Restoration. Miriam & IRA D. Wallach Art Gallery (2004). ISBN 1-884919-15-4

- Ousterhout, Robert G. (1988). The Architecture of the Kariye Camii in Istanbul. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. ISBN 978-0-88402-165-0.

- Robert Ousterhout (Editor), Leslie Brubaker (Editor). The Sacred Image East and West. University of Illinois Press (1994). ISBN 978-0-252-02096-4

- Saint Saviour in Chora. A Turizm Yayınları Ltd. (1988). ASIN B000FK8854

- Cevdet Turkay. Kariye Mosque. (1964). ASIN B000IUWV2C

- Paul A. Underwood. The Kariye Djami in 3 Volumes. Bollingen (1966). ASIN B000WMDL7U

- Paul A. Underwood. Third Preliminary Report on the Restoration of the Frescoes in the Kariye Camii at Istanbul. Harvard University Press (1958). ASIN B000IBCESM

- Edda Renker Weissenbacher. Kariye: The Chora Church, Step by Step. ASIN B000RBATF8

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kariye Museum. |

- | Go Turkey - Turkish Tourism Promotion and Development Agency

- | Official Website

- Columbia University | Restoring Byzantium | The Kariye Camii in Istanbul and the Byzantine Institute Restoration

- Byzantium 1200 | Chora Monastery

- Interior and exterior pictures in http://rubens.anu.edu.au (Dead link)

- Photos with explanations

- BYZANTINE MOSAICS OF CHORA MONASTERY Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Well over 500 pictures of the Chora museum

Coordinates: 41°01′52″N 28°56′21″E / 41.03111°N 28.93917°E

- Churches and monasteries of Constantinople

- Mosques converted from churches in Istanbul

- 11th-century Roman Catholic church buildings

- Church buildings with domes

- Byzantine church buildings in Istanbul

- Museums in Istanbul

- Byzantine art

- Fatih

- Religious museums in Turkey

- Byzantine museums in Turkey

- Historic sites in Turkey

- Churches in Istanbul

- Former churches in Turkey

- Mosques converted from churches in Turkey