Chronic bacterial prostatitis

| Chronic Bacterial Prostatitis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Specialty | Urology |

Chronic bacterial prostatitis is a bacterial infection of the prostate gland. It should be distinguished from other forms of prostatitis such as acute bacterial prostatitis and chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS).[1]

Signs and symptoms[]

Chronic bacterial prostatitis is a relatively rare condition that usually presents with an intermittent UTI-type picture. It is defined as recurrent urinary tract infections in men originating from a chronic infection in the prostate. Symptoms may be completely absent until there is also bladder infection, and the most troublesome problem is usually recurrent cystitis.[2]

Chronic bacterial prostatitis occurs in less than 5% of patients with prostate-related non-BPH lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS).[citation needed]

Dr. Weidner, Professor of Medicine, Department of Urology, University of Gießen, has stated: "In studies of 656 men, we seldom found chronic bacterial prostatitis. It is truly a rare disease. Most of those were E-coli."[3]

Diagnosis[]

In chronic bacterial prostatitis, there are bacteria in the prostate, but there may be no symptoms or milder symptoms than occur with acute prostatitis.[4] The prostate infection is diagnosed by culturing urine as well as prostate fluid (expressed prostatic secretions or EPS) which are obtained by the doctor performing a rectal exam and putting pressure on the prostate. If no fluid is recovered after this prostatic massage, a post massage urine should also contain any prostatic bacteria.[citation needed]

Prostate specific antigen levels may be elevated, although there is no malignancy. Semen analysis is a useful diagnostic tool.[5] Semen cultures are also performed. Antibiotic sensitivity testing is also done to select the appropriate antibiotic. Other useful markers of infection are seminal elastase and seminal cytokines.[citation needed]

Treatment[]

Antibiotic therapy has to overcome the blood/prostate barrier that prevents many antibiotics from reaching levels that are higher than minimum inhibitory concentration.[6] A blood-prostate barrier restricts cell and molecular movement across the rat ventral prostate epithelium.[7] Treatment requires prolonged courses (4–8 weeks) of antibiotics that penetrate the prostate well.[8] The fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines and macrolides have the best penetration. There have been contradictory findings regarding the penetrability of nitrofurantoin[contradictory], quinolones (ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin), sulfas (Bactrim, Septra), doxycycline and macrolides (erythromycin, clarithromycin). This is particularly true for gram-positive infections.[citation needed]

In a review of multiple studies, levofloxacin was found to reach prostatic fluid concentrations 5.5 times higher than ciprofloxacin, indicating a greater ability to penetrate the prostate.[9]

Clinical success rates with oral antibiotics can reach 70% to 90% at 6 months, although trials comparing them with placebo or no treatment do not exist.[10]

Persistent infections may be helped in 80% of patients by the use of alpha blockers (tamsulosin, alfuzosin), or long term low dose antibiotic therapy.[11] Recurrent infections may be caused by inefficient urination (benign prostatic hypertrophy, neurogenic bladder), prostatic stones or a structural abnormality that acts as a reservoir for infection.[citation needed]

In theory, the ability of some strains of bacteria to form biofilms might be one of the factors that facilitate development of chronic bacterial prostatitis.[12]

Bacteriophages hold promise as another potential treatment for chronic bacterial prostatatis.[13]

The addition of prostate massage to courses of antibiotics was previously proposed as being beneficial and prostate massage may mechanically break up the biofilm and enhance the drainage of the prostate gland.[14][15] However, in more recent trials, this was not shown to improve outcome compared to antibiotics alone.[16]

Prognosis[]

Over time, the relapse rate is high, exceeding 50%. However, recent research indicates that combination therapies offer a better prognosis than antibiotics alone.

A 2007 study showed that repeated combination pharmacological therapy with antibacterial agents (ciprofloxacin/azithromycin), alpha-blockers (alfuzosin) and Serenoa repens extracts may eradicate infection in 83.9% of patients with clinical remission extending throughout a follow-up period of 30 months for 94% of these patients.[17]

A 2014 study of 210 patients randomized into two treatment groups found that recurrence occurred within 2 months in 27.6% of the group using antibiotics alone (prulifloxacin 600 mg), but in only 7.8% of the group taking prulifloxacin in combination with Serenoa repens extract, Lactobacillus Sporogens and Arbutin.[18]

Large prostatic stones was shown to be related with the presence of bacteria,[19] a higher urinary symptoms and pain score, a higher IL-1β and IL-8 concentration in seminal plasma, a greater prostatic inflammation and a lower response to antibiotic treatment.[20]

Additional images[]

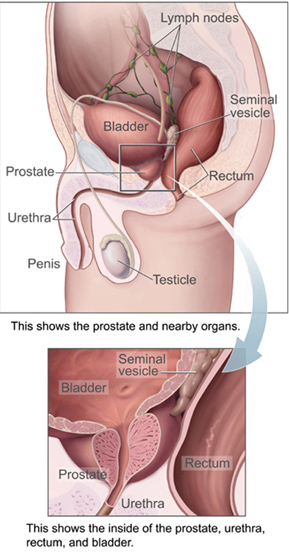

Prostate, urethra, and seminal vesicles.

The arteries of the pelvis.

Male pelvic organs seen from right side.

References[]

- ^ Holt JD, Garrett WA, McCurry TK, Teichman JM (February 2016). "Common Questions About Chronic Prostatitis". American Family Physician. 93 (4): 290–6. PMID 26926816.

- ^ Habermacher GM, Chason JT, Schaeffer AJ (2006). "Prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". Annual Review of Medicine. 57 (1): 195–206. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.57.011205.135654. PMID 16409145.

- ^ Schneider H, Ludwig M, Hossain HM, Diemer T, Weidner W (October 2003). "The 2001 Giessen Cohort Study on patients with prostatitis syndrome--an evaluation of inflammatory status and search for microorganisms 10 years after a first analysis". Andrologia. 35 (5): 258–62. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0272.2003.00586.x. PMID 14535851. S2CID 21022117.

- ^ "Prostatitis - Symptoms". NHS Choices. 2017-10-19.

- ^ Magri V, Wagenlehner FM, Montanari E, Marras E, Orlandi V, Restelli A, et al. (July 2009). "Semen analysis in chronic bacterial prostatitis: diagnostic and therapeutic implications". Asian Journal of Andrology. 11 (4): 461–77. doi:10.1038/aja.2009.5. PMC 3735310. PMID 19377490.

- ^ Fulmer BR, Turner TT (May 2000). "A blood-prostate barrier restricts cell and molecular movement across the rat ventral prostate epithelium". The Journal of Urology. 163 (5): 1591–4. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(05)67685-9. PMID 10751894.

- ^ Barza M (January 1993). "Anatomical barriers for antimicrobial agents". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 12 Suppl 1 (Suppl 1): S31-5. doi:10.1007/BF02389875. PMID 8477760. S2CID 23753756.

- ^ Charalabopoulos K, Karachalios G, Baltogiannis D, Charalabopoulos A, Giannakopoulos X, Sofikitis N (December 2003). "Penetration of antimicrobial agents into the prostate" (PDF). Chemotherapy. 49 (6): 269–79. doi:10.1159/000074526. PMID 14671426. S2CID 14731590.

- ^ "Levofloxacin and Its Effective Use in the Review Management of Bacterial Prostatitis" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-09. Retrieved 2016-02-08.

- ^ Bowen DK, Dielubanza E, Schaeffer AJ (August 2015). "Chronic bacterial prostatitis and chronic pelvic pain syndrome". BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2015: 1802–1831. PMC 4551133. PMID 26313612.

- ^ Shoskes DA, Hakim L, Ghoniem G, Jackson CL (April 2003). "Long-term results of multimodal therapy for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome". The Journal of Urology. 169 (4): 1406–10. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000055549.95490.3c. PMID 12629373.

- ^ Wagenlehner FM, Pilatz A, Bschleipfer T, Diemer T, Linn T, Meinhardt A, et al. (August 2013). "Bacterial prostatitis". World Journal of Urology. 31 (4): 711–6. doi:10.1007/s00345-013-1055-x. PMID 23519458. S2CID 1925596.

- ^ Letkiewicz S, Międzybrodzki R, Kłak M, Jończyk E, Weber-Dąbrowska B, Górski A (November 2010). "The perspectives of the application of phage therapy in chronic bacterial prostatitis". FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 60 (2): 99–112. doi:10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00723.x. PMID 20698884.

- ^ Nickel JC, Downey J, Feliciano AE, Hennenfent B (September 1999). "Repetitive prostatic massage therapy for chronic refractory prostatitis: the Philippine experience". Techniques in Urology. 5 (3): 146–51. PMID 10527258.

- ^ Shoskes DA, Zeitlin SI (May 1999). "Use of prostatic massage in combination with antibiotics in the treatment of chronic prostatitis". Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases. 2 (3): 159–162. doi:10.1038/sj.pcan.4500308. PMID 12496826.

- ^ Ateya A, Fayez A, Hani R, Zohdy W, Gabbar MA, Shamloul R (April 2006). "Evaluation of prostatic massage in treatment of chronic prostatitis". Urology. 67 (4): 674–8. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2005.10.021. PMID 16566972.

- ^ Magri V, Trinchieri A, Pozzi G, Restelli A, Garlaschi MC, Torresani E, et al. (May 2007). "Efficacy of repeated cycles of combination therapy for the eradication of infecting organisms in chronic bacterial prostatitis". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 29 (5): 549–56. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.09.027. PMID 17336504.

- ^ Busetto GM, Giovannone R, Ferro M, Tricarico S, Del Giudice F, Matei DV, et al. (July 2014). "Chronic bacterial prostatitis: efficacy of short-lasting antibiotic therapy with prulifloxacin (Unidrox®) in association with saw palmetto extract, lactobacillus sporogens and arbutin (Lactorepens®)". BMC Urology. 14 (1): 53. doi:10.1186/1471-2490-14-53. PMC 4108969. PMID 25038794.

- ^ Mazzoli, Sandra (August 2010). "Biofilms in chronic bacterial prostatitis (NIH-II) and in prostatic calcifications". FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 59 (3): 337–344. doi:10.1111/j.1574-695X.2010.00659.x. ISSN 1574-695X. PMID 20298500.

- ^ Soric, Tomislav; Selimovic, Mirnes; Bakovic, Lada; Šimurina, Tatjana; Selthofer, Robert; Dumic, Jerka (2017). "Clinical and Biochemical Influence of Prostatic Stones". Urologia Internationalis. 98 (4): 449–455. doi:10.1159/000455161. ISSN 1423-0399. PMID 28052296. S2CID 4927272.

External links[]

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Bacterial diseases

- Sexually transmitted diseases and infections

- Inflammatory prostate disorders