Convict leasing

| Part of a series on the |

| Nadir of American race relations |

|---|

|

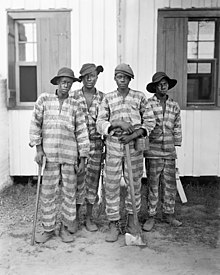

Convict leasing was a system of forced penal labor which was historically practiced in the Southern United States and overwhelmingly involved African-American men. Recently, a form of the practice (which draws voluntary labor from the general prison population) has been instituted in western states.[1] In the earlier forms of the practice, convict leasing provided prisoner labor to private parties, such as plantation owners and corporations (e.g. Tennessee Coal and Iron Company, Chattahoochee Brick Company). The lessee was responsible for feeding, clothing, and housing the prisoners.

The state of Louisiana leased out convicts as early as 1844,[2] but the system expanded all through the South with the emancipation of slaves at the end of the American Civil War in 1865. It could be lucrative for the states: in 1898, some 73% of Alabama's entire annual state revenue came from convict leasing.[3]

While Northern states sometimes contracted for prison labor, the historian Alex Lichtenstein notes that "only in the South did the state entirely give up its control to the contractor; and only in the South did the physical "penitentiary" become virtually synonymous with the various private enterprises in which convicts labored."[4]

Corruption, lack of accountability, and racial violence resulted in "one of the harshest and most exploitative labor systems known in American history."[5] African Americans, mostly adult males, due to "vigorous and selective enforcement of laws and discriminatory sentencing", made up the vast majority—though not all—of the convicts leased.[6]

The writer Douglas A. Blackmon described the system: "It was a form of bondage distinctly different from that of the antebellum South in that for most men, and the relatively few women drawn in, this slavery did not last a lifetime and did not automatically extend from one generation to the next. But it was nonetheless slavery – a system in which armies of free men, guilty of no crimes and entitled by law to freedom, were compelled to labor without compensation, were repeatedly bought and sold, and were forced to do the bidding of white masters through the regular application of extraordinary physical coercion."[7]

U.S. Steel is among American companies who have acknowledged using African-American leased convict labor.[8] The practice peaked around 1880, was formally outlawed by the last state (Alabama) in 1928, and persisted in various forms until it was abolished by President Franklin D. Roosevelt via Francis Biddle's "Circular 3591" of December 12, 1941.

Origins[]

Convict leasing in the United States was widespread in the South during the Reconstruction Period (1865–1877) after the end of the Civil War, when many Southern legislatures were ruled by majority coalitions of blacks and Radical Republicans,[9][10] and Union generals acted as military governors. Farmers and businessmen needed to find replacements for the labor force once their slaves had been freed. Some Southern legislatures passed Black Codes to restrict free movement of blacks and force them into employment with whites. For instance, several states made it illegal for a black man to change jobs without the approval of his employer.[11] If convicted of vagrancy, blacks could be imprisoned, and they also received sentences for a variety of petty offenses. States began to lease convict labor to the plantations and other facilities seeking labor, as the freed men were trying to withdraw and work for themselves. This provided the states with a new source of revenue during years when they were financially strapped, and lessees profited by the use of forced labor at below-market rates.[12]

Essentially, the criminal justice system colluded with private planters and other business owners to entrap, convict, and lease blacks as prison laborers.[12] The constitutional basis for convict leasing is that the 1865 Thirteenth Amendment, while abolishing slavery and involuntary servitude generally, permits it as a punishment for crime.

The criminologist Thorsten Sellin, in his book Slavery and the Penal System (1976), wrote that the sole aim of convict leasing "was financial profit to the lessees who exploited the labor of the prisoners to the fullest, and to the government which sold the convicts to the lessees."[13] The practice became widespread and was used to supply labor to farming, railroad, mining, and logging operations throughout the South.

The system in various states[]

In Georgia convict leasing began in April 1868, when Union General and newly appointed provisional governor Thomas H. Ruger issued a convict lease for prisoners to William Fort for work on the Georgia and Alabama Railroad.[10] The contract specified "one hundred able bodied and healthy Negro convicts" in return for a fee to the state of $2500.[14] In May the state entered into a second agreement with Fort and his business partner Joseph Printup for another 100 convicts, this time for $1000, to work on the Selma, Rome and Dalton Railroad, also in north Georgia.[15] Georgia ended the convict lease system in 1908.

In Tennessee, the convict leasing system was halted on January 1, 1894 because of the attention brought by the Coal Creek War of 1891, an armed labor action lasting over a year. At the time both free and convict labor were used in mines, although workers were kept separated. Free coal miners attacked and burned prison stockades, and freed hundreds of black convicts; the related publicity and outrage turned Governor John P. Buchanan out of office.

The end of convict leasing did not mean the end of convict labor, however. The state sited its new penitentiary, Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary, with the help of geologists. The prison built a working coal mine on the site, dependent on labor done by prisoners, and ran it at significant profit. These prison mines closed in 1966.[16]

Texas began convict leasing by 1883 and officially abolished it in 1910.[17] A cemetery containing what are believed to be the remains of 95 "slave convicts" has recently (2018) been discovered in Sugar Land, today a suburb of Houston.[18]

The Convict Lease System and Lynch Law are twin infamies which flourish hand in hand in many of the United States. They are the two great outgrowths and results of the class legislation under which our people suffer to-day.

Alabama began convict leasing in 1846 and outlawed it in 1928. It was the last state to formally outlaw it. The revenues derived from convict leasing were substantial, accounting for roughly 10% of total state revenues in 1883,[20] surging to nearly 73% by 1898.[3] An abolition movement against convict leasing in Alabama began in 1915. Bibb Graves, who became Alabama's governor in 1927, had promised during his election campaign to abolish convict leasing as soon as he was inaugurated, and this was finally achieved by the end of June 1928.[21]

This lucrative practice created incentives for states and counties to convict African Americans, and helped raise the prison population in the South to become predominantly African-American following the Civil War.[citation needed] In Tennessee, African Americans represented 33 percent of the population at the main prison in Nashville as of October 1, 1865, but by November 29, 1867, their percentage had increased to 58.3. By 1869, it had increased to 64 percent, and it reached an all-time high of 67 percent between 1877 and 1879.[13]

Prison populations also increased overall in the South. In Georgia prison populations increased tenfold during the four-decade period (1868–1908) when it used convict leasing; in North Carolina the prison population increased from 121 in 1870 to 1,302 in 1890; in Florida the population went from 125 in 1881 to 1,071 in 1904; in Mississippi the population quadrupled between 1871 and 1879; in Alabama it went from 374 in 1869 to 1,878 in 1903; and to 2,453 in 1919.[13]

In Florida, convicts, who were often African American, were sent to work in turpentine factories and lumber camps. The convict labor system in Florida was described as being "severe", compared to other states.[12] Florida was one of the last states to end convict leasing, in 1923 (see Union Correctional Institution).

End of the system[]

Although the beginning of the 20th century brought increasing opposition to the system, state politicians resisted calls for its elimination. In states where the convict lease system was used, revenues from the program generated income nearly four times the cost (372%) of prison administration.[22] The practice was extremely profitable for the governments, as well as for those business-owners who used convict labor. However, other problems accompanied convict leasing and, overall, employers became more aware of the disadvantages.[23]

While some believe the demise of the system can be attributed to exposure of the inhumane treatment suffered by the convicts,[24] others point toward causes ranging from comprehensive legislative reform packages to political retribution or payback.[22] Though the convict lease system, as such, disappeared, other forms of convict labor continued (and still exist today) in various forms. These other systems include plantations, industrial prisons, and the infamous "chain gang".[13]

The convict lease system was gradually phased out in the early 20th century amid negative publicity and other factors. A notable case of negative publicity for the system was the case of Martin Tabert, a young white man from North Dakota. Arrested on a charge of vagrancy for being on a train without a ticket in Tallahassee, Florida, Tabert was convicted and fined $25.[25] Although his parents sent $25 for the fine, plus $25 for Tabert to return home to North Dakota, the money disappeared in the Leon County prison system. Tabert was then leased to the Putnam Lumber Company in Clara, Florida, approximately 60 miles (97 km) south of Tallahassee in Dixie County.[25] There, he was flogged to death by the whipping boss, Thomas Walter Higginbotham.[26] Coverage of Tabert's killing by the New York World newspaper in 1924 earned it the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service. Governor Cary A. Hardee ended convict leasing in 1923, in part spurred on by the Tabert case and the resulting publicity.

North Carolina, while without a system comparable to the other states, did not prohibit the practice until 1933. Alabama was the last to end the practice of official convict leasing in 1928 by the State,[27] but many counties in the South continued the practice for years.[11]

See also[]

- Convict assignment (Australia)

- Federal Prison Industries

- Field holler

- Field slaves in the United States

- History of unfree labor in the United States

- Penal labor in the United States

- Ruiz v. Estelle

- Slavery in the 21st century#Prison labor

- Trusty system

References[]

- ^ Agriculture farmers turn to prisons labor to fill labor needs

- ^ Punishment in America: A Reference Handbook, by Cyndi Banks, page 58

- ^ Jump up to: a b Robert Perkinson (2010). Texas Tough: The Rise of America's Prison Empire. Henry Holt and Company. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-429-95277-4.

- ^ Alex Lichtenstein, Twice the Work of Free Labor: The Political Economy of Convict Labor in the New South, Verso Press, 1996, p. 3

- ^ Mancini, Matthew J. (1996). One Dies, Get Another: Convict Leasing in the American South, 1866-1928. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9781570030833. p. 1-2.

- ^ Litwack, Leon F. Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow, (1998) ISBN 0-394-52778-X, p. 271

- ^ Blackmon, Douglas A. Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II, (2008) ISBN 978-0-385-50625-0, p. 4

- ^ "Book: American Slavery Continued Until 1941". Newsweek. July 13, 2008.

- ^ Foner, Eric (January 31, 2018). "South Carolina's Forgotten Black Political Revolution". Slate Magazine.

- ^ Jump up to: a b The Georgia and Alabama Railroad formed in 1850 by Georgia state charter to organize rail service between Rome and the Alabama state line. Never financially healthy, the company managed to operate until after the Civil War; it was unrelated to later rail companies of the same name. See Fairfax Harrison's A History of the Legal Development of the Railroad System of Southern Railway Company, 1901/reprint 2012 General Books, p. 790

- ^ Jump up to: a b Slavery by another name

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Convicts Leased to Harvest Timber". World Digital Library. 1915. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "The Black Commentator - Slavery in the Third Millennium, Part II - Issue 142". blackcommentator.com.

- ^ Lichtenstein (1996), Twice the Work of Free Labor, pp. 41-42

- ^ Lichtenstein (1996), Twice the Work of Free Labor, p. 42

- ^ W. Calvin Dickinson, "Brushy Mountain Prison"], Southern History, July 1, 2003

- ^ "Handbook of Texas Online". Retrieved December 8, 2007.

- ^ Gannon, Megan (July 20, 2018). "Century-Old Burials of 95 Convict Slaves Uncovered in Texas". Live Science.

- ^ Frederick Douglass, "The Convict Lease System", from The Reason Why the Coloured American Is Not in the World's Colombian Exposition (1893)

- ^ "Digital History". digitalhistory.uh.edu.

- ^ "Alabama Ends Convict Leasing". The New York Times. July 1, 1928.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mancini, M. (1978). "Race, Economics, and the Abandonment of Convict Leasing", Journal of Negro History, 63(4), 339–340. Retrieved October 1, 2006, from JSTOR database.

- ^ "Forced Labor in the 19th Century South: The Story of Parchman Farm" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved December 8, 2007.

- ^ Todd, W. (2005). "Convict Lease System", In The New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved October 1, 2006, from [1]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Staff (2013). "Timeline: 1921". Florida Department of Corrections. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

- ^ "Whipping Boss will Go Free", Associated Press, Jul 17, 1925, quoted in Miami News, from news.google.com

- ^ Fierce, Milfred (1994). Slavery Revisited: Blacks and the Southern Convict Lease System, 1865-1933. New York: Africana Studies Research Center, Brooklyn College, City University of New York. pp. 192–193. ISBN 0-9643248-0-6.

Further reading[]

- Blackmon, Douglas A. Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II, New York: Anchor Books, Random House Publishing, 2008. ISBN 0-385-72270-2.

- Kahn, Si, and Elizabeth Minnich. The Fox in the Henhouse: How Privatization Threatens Democracy, San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2005. ISBN 1-57675-337-9.

- Moulder, Rebecca, H. "Convicts as Capital: Thomas O'Conner and the Leases of the Tennessee Penitentiary System, 1871–1883", East Tennessee Historical Society Publications, no. 48 (1976): 58–59.

- Oshinsky, David M. Worse Than Slavery: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice. New York: The Free Press, 1996. ISBN 0-684-82298-9.

- Blue, Ethan. "Doing Time in the Depression: Everyday Life in Texas and California Prison". New York: New York University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0-8147-0940-5.

- Staples, Brent (October 27, 2018). "A Fate Worse Than Slavery, Unearthed in Sugar Land". The New York Times.

- Cardon, Nathan. "'Less Than Mayhem': Louisiana's Convict Lease, 1865-1901" Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana History Association (Fall, 2017): 416-439.

- Shapiro, Karen. A New South Rebellion: The Battle Against Convict Labor in the Tennessee Coalfields, 1871-1896 (University of North Carolina Press, 1998).

- Lichtenstein, Alex. Twice the Work of Free Labor: The Political Economy of Convict Labor in the New South (Verso, 1996).

External links[]

- Powell, J.C., The American Siberia (1891), memoir of 14 years in a Florida convict camp; full text online at GoogleBooks

- Waters, Robert. "Convict Leasing in Florida, or A Postcard from a Southern Siberia", June 2007, guest post at Laura James' CLEWS, a literary blog about crime

- African-American history between emancipation and the civil rights movement

- Agricultural labor in the United States

- Anti-black racism in the United States

- History of African-American civil rights

- Imprisonment and detention in the United States

- Jim Crow

- Legal history of the United States

- Penal labor in the United States

- Race legislation in the United States

- Reconstruction Era

- United States repealed legislation

- White supremacy in the United States