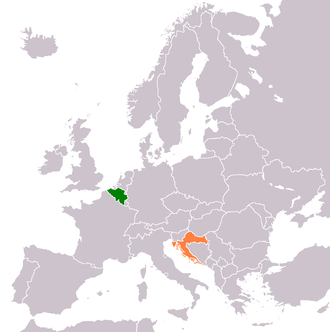

Croats of Belgium

| Part of a series on |

| Croats |

|---|

|

Croats of Belgium are an ethnic group in Belgium. About 10,000 of Belgians stated that they have Croatian roots, according to the Croatian associations and Catholic missions. They appeared in Belgium for the first time during the Thirty Years' War, as a part of Austrian and French cavalry. Even today, the exact number of Croats in Belgium is unknown, mostly because they were considered as Yugoslavs by Belgian government. During the last years, number of Croats in Belgium is increasing because of immigrants from Bosnia and Herzegovina. The number of Croats didn't pass the number of 10,000 since the World War II when Croatia was part of a larger country Yugoslavia.

History[]

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor had settled Croats in Flanders around the Dunkerque (then Duinkerken) to serve him as soldiers. Later, Croatian travel writer, , in 17th century found that there are still Croats in Belgium, who still speak Croatian.[1][2] Those Croats were Uskoks from Senj.[3]

In that time, Dunkerque was part of Netherlands as whole Belgium also. In year 1662 town of Dunkerque became part of France as King of England, Charles II sold it to the French.

Early 20th century[]

As Belgium was one of the most developed states in Europe in the early 20th century, part of Croats emigrated in it searching for better life. Moreover, the first wave of emigration started with creation of Kingdom of Yugoslavia and because of anti-Croatian politics of that state in 1918. Most of emigrants were peasants and workers from Bosnia, Herzegovina, Dalmatia and Lika. Croats were mostly workers at steel foundry, ironworks, mines of coal and such. At first, Croats done the hardest jobs, but they were highly respected for their famous devoted work and cleverness. Soon, Croats become employers and chiefs to some Belgians.

After the assassination of Stjepan Radić and of Yugoslav King Alexander I in 1928-1929, and the consequent repression against Croatian nationalism, the number of Croats in Belgium increased, including many members of the Ustaše movement, secretly active also in Belgium, among which the Herzegovinian Croat general Rafael Boban, later US Army officer.

At the time, the number of Croats in Belgium was 25,000 to 30,000. Most of Croats resided in Wallonia in the cities of Liège and Charleroi and in their surroundings.

In 1932, under the influence of the brothers Antun and Stjepan Radić, Belgian Croats founded the first branch of the Croatian Peasant Party abroad in Jemeppe-sur-Sambre near Liège. The branch was later registered as the Mutual Aid Association "Croatian Peasant Party" (Croatian: "Hrvatski seljački savez"). They couldn't act like a political organization because of Belgian laws and the protests of the Yugoslav government.

Before World War II only a small number of Croats had university degrees - among them dr. and economist . In time of World War II most of Croats had stayed in Belgium, only the members of Ustaše left the country for Croatia. After the war, big part of Croats leaves industrial sector and employees in the trade sector, where they have big successes. Also, big number of Croats arrives in new, communist Yugoslavia, but soon, disappointed with communist policy, they again leave the country, but this time they emigrate to overseas. The Croats that remained in Belgium often married with Belgian women, because the amount of Croat women in Belgium at the time was very small.

Post-war migration wave[]

The first part of the second wave of immigration was composed of political emigrants. Thousands of Croats flees SFR Yugoslavia, big part of them were former Ustaše and Domobran soldiers. Most of those Ustaše emigrants soon left Belgium for other destinations overseas (Canada, United States, Australia). Those political emigrants who stayed in Belgium received asylum from United Nations.

Also thanks to this new influx, the Croatian Peasant Party in Belgium saw a revival; the party leader, Vladko Maček, resided in exile in Paris until death in 1964. The branch organised ceremonies, cultural programs and celebrations on the anniversary of the death of Stjepan Radić. There was also a branch of the Croatian National Committee, an Ustaše-linked organization in Belgium. They convened a Second Assembly in Brussels in 1977, which was met with fierce criticism from the Yugoslav government. Assemblies of Croats were also organized by the priests who gather them on ceremonies and mass.

The Croatian Peasant Party also organised a trade union, the Croatian Worker's Union (Hrvatski radnički savez), with headquarters in Charleroi. There were also few sport and cultural societies, of which some are still active today. Among others, there were also few Yugoslav clubs under the patronage of the Yugoslav embassy, which served for espionage of Croats in Belgium.

Except for a few newsletters, there was also a monthly newspapers Hrvatski glas ("Croatian voice") that had been published in the 1950s and 1960s as formal newspapers of Croatian Peasant Party in Europe. They were edited by Oton Orešković, who was a former quartermaster of Croatian National Theatre. Those newspapers were printed on their own linotype which was a gift from the American trade union AFL-CIO to the Croatian Worker's Union. Oton Orešković, in cooperation with Delonoy published a comprehensive study in the review Historia on Ante Pavelić's rise to power until his life in exile.

A further wave of immigration started after the quelling of the Croatian Spring by the Yugoslav communist regime in 1971. Thousands of Croats fled again to Belgium, some of them individually and some with their family. Most of them Croats soon left Belgium for Canada and Australia, smaller part went in United States, New Zealand and South America. Also, some of them scattered all around Europe. Soon Croats with higher education also moved from Belgium. After the 1970s and the death of communist dictator Josip Broz Tito, only Croats who worked for Yugoslav companies arrived in Belgium.

The real political life of Belgian Croats started with the foundation of Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) and arrival of Franjo Tuđman on the Croatian political scene. The first Croats of Belgium registered as HDZ members even before the first democratic elections. With sequence of events, Croats of Belgium founded branches of Croatian Democratic Union (in 1990 and 1991) in Antwerp, Brussels and Liège. The founders were later immigrants who came after World War II, and in less numbers, heirs of immigrants from the first wave of immigration. Croats in Belgium mostly helped financially by sending money to hospitals, charities and military budget. The money came mainly through HDZ branches. At the start of Croatian Homeland War, Belgian Croats founded Croatian Supplementary School, under patronage of the .

Croats in Belgium today[]

Croatian political organizations that are still active are branches of Croatian Democratic Union, Croatian Peasant Party and Croatian Liberation Movement. Other active Croatian organizations are the Sport and Cultural Society "Croatia" from Antwerp, "SOS-Croatia" from Merchtem near Brussels, "HNK Croatia" (Croatian National Theater "Croatia") in Liège, association of Croatian students "AMAC" in Brussels, charity organization "Edmond Jardas" (they are mostly helping children of killed Croatian soldiers), Cultural society "Vatroslav Lisinski" from Liège, "Hrvatski radio sat" ("Croatian Radio Hour") from Liège (founded by members of HSK and Belgian-born Croats, promoting Croatian culture, tourism and return of Croats back to homeland). The head organization is the Croatian World Congress of Belgium led by Dr. .

One of the most important factors in saving of Croatian identity in Belgium is the Catholic Church. Because of misunderstanding of Croatian emigration and Government in Croatia those organizations and societies are being reduced.[citation needed]

Demography[]

It is difficult to determine with certainty the number, age structure of Croats in Belgium, their economic status and level of national identity, especially among the descendants of the first settlers. The biggest number of Croats, 5,000-6,000 from first and third generation, still live in Wallonia in area Liège. Croatian immigrants from the first wave of immigration who moved to Belgium in the late 1920s are almost all dead, so their children and later immigrants represent the Croats of Belgium. A very small number of Croats have returned to their homeland, especially the heirs of the first immigrants.

Later, most Croatian immigrants settled around the area of Brussels and Antwerp in Flanders where the economic situation is nowadays better. The Croatian national identity is still strong, even with the third generation of immigrants, even though there is a small number of those who know they are Croats, but Croatia doesn't mean much to them. Also, there are increasing applications at Croatian schools and interest in Croatian. The first generation were mostly workers, while the second and third generation had better education and employment.

Notable Croats in Belgium[]

The contribution of Croats to development of Belgium is mostly due to hard-working Croats who worked in Belgian factories and mines. After World War II, Croats of Belgium had three university professors: Dr. , geneticist; Dr. Miroslav Radman, sociologist; and other few doctors, professors, lawyers, economists, academic painters and architects.

Besides, Croats also contributed to the Belgian sports. The most famous sportsmen are Tomislav Ivić, Mario Stanić, Robert Špehar, Josip Weber and others. Few Croats also successfully imported canned fish, medicinal plants and vines (Fabris, Divić, Vunić). Croats also work in catering, radios and various Belgian ministries.

- Junior Lefevre, karateka

- Jean-Philippe Susilovic, maître on Hell's Kitchen Belgium

- Jerko Tipurić, football manager and former footballer

- Tino-Sven Sušić, Bosnian Croat footballer

See also[]

- Belgium–Croatia relations

- Croats

- List of Croats

References[]

- ^ Josip Horvat: Povijest i kultura Hrvata kroz 1000. godina: od velikih seoba do 18. stoljeća, Knjigotisak, Split, 2009. str. 239

- ^ HIC-Dom i svijet br.379/2002. Croats of France

- ^ Archive.org Vjekoslav Klaić: Povijest Hrvata od najstarijih vremena do svretka XIX. stoljeća

- Croatian diaspora by country

- Ethnic groups in Belgium

- Belgian people of Croatian descent