Drew, Mississippi

Drew, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

| |

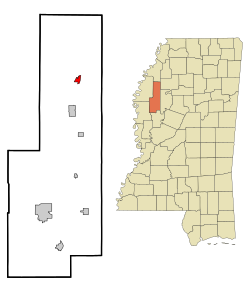

Location of Drew, Mississippi | |

Drew, Mississippi Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 33°48′36″N 90°31′50″W / 33.81000°N 90.53056°WCoordinates: 33°48′36″N 90°31′50″W / 33.81000°N 90.53056°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| County | Sunflower |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.12 sq mi (2.91 km2) |

| • Land | 1.12 sq mi (2.91 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 135 ft (41 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 1,927 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 1,608 |

| • Density | 1,433.16/sq mi (553.36/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 38737-38738 |

| Area code(s) | 662 |

| FIPS code | 28-20020 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0669383 |

Drew is a city in Sunflower County, Mississippi. The population was 1,927 at the 2010 census. Drew is in the vicinity of several plantations and the Mississippi State Penitentiary, a Mississippi Department of Corrections prison for men. It is noted for several racist murders, including the lynching of Emmett Till in 1955.

History[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (February 2012) |

When the Yellow Dog Railroad was extended through what is now Drew, the post office was moved from the Promised Land Plantation to the Drew location. The settlement and Post Office for Miss Drew Daniel, daughter of Andrew Jackson Daniel.[3]

A school called the Little Red Schoolhouse was built by matching funds from the Rosenwald Fund in 1928. In the 21st century it received a grant for renovation of the large school.[4]

In the 1920s, a man named Joe Pullen was lynched near Drew after killing 13 members of his lynch mob and injuring 26 of them.[5]

One historian wrote that the white residents of Drew had "traditionally been regarded as the most recalcitrant in the county on racial matters."[6] The author wrote that whites in Drew were "considered the most recalcitrant of Sunflower County, and perhaps the state."[5] He also claimed that Drew's proximity to the Mississippi State Penitentiary made Drew "a dangerous place to be black", and claimed that during the 1930s and 1940s many police officers arbitrarily shot blacks, saying that they appeared to look like escaped prisoners.[5] That historian also claimed that during the Civil Rights Movement, when attempts were made to move Fannie Lou Hamer's movement for poor people from Ruleville to Drew, the organizers "faced stiff resistance". Mae Bertha Carter, a major figure in the area civil rights movement, was from Drew.[6]

In August of 1955, 14 year old Emmett Till was tortured and murdered in a barn near Drew. His killers then disposed of his body in the nearby Tallahatchie River. The racist lynching became nationally known for its brutality, and because of Till's mother's choice to have an open-casket funeral for her son. According to the FBI agent assigned to the case, the killers chose the barn in Drew because they thought it was a place where no one who would object to the murder would see or overhear the events. However, a young man from Drew named Willie Reed witnessed the murder and testified in court. The accused murders were acquitted in court, but later confessed to the killing in a magazine interview. As of 2021 there is no memorial marking the site of the killing, which is located on private property.[7]

Geography[]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 1.1 square miles (2.8 km2), all land. Because of its small size, Billy Turner of The Times-Picayune said "[y]ou can travel all over town in a few minutes."[8] Drew is in the vicinity of several plantations and the Mississippi State Penitentiary (Parchman), a Mississippi Department of Corrections prison for men.[9]

Drew, in northern Sunflower County,[10] is located on U.S. Route 49W, on the route between Jackson and Clarksdale.[11] Drew is 8 miles (13 km) south of the Mississippi State Penitentiary,[12] and it is north of Ruleville.[6] Cleveland, Mississippi is 12 miles (19 km) from Drew. Drew is north of Yazoo City.[8]

Many houses in Drew are government-owned. Some houses sold for $6,000 to $8,000 in the year until Saturday January 26, 2008. Some Drew residents said in 2008 that some houses, if put on the market, would sell for over $120,000.[8]

Demographics[]

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1900 | 195 | — | |

| 1910 | 278 | 42.6% | |

| 1920 | 721 | 159.4% | |

| 1930 | 1,373 | 90.4% | |

| 1940 | 1,579 | 15.0% | |

| 1950 | 1,681 | 6.5% | |

| 1960 | 2,143 | 27.5% | |

| 1970 | 2,574 | 20.1% | |

| 1980 | 2,528 | −1.8% | |

| 1990 | 2,349 | −7.1% | |

| 2000 | 2,434 | 3.6% | |

| 2010 | 1,927 | −20.8% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 1,608 | [2] | −16.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[13] | |||

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 1,927 people living in the city. The racial makeup of the city was 82.7% Black, 16.0% White, 0.2% Native American, 0.2% Asian and 0.2% from two or more races. 0.7% were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

As of the census[14] of 2000, there were 2,434 people, 811 households, and 606 families living in the city. The population density was 2,172.6 people per square mile (839.1/km2). There were 922 housing units at an average density of 823.0 per square mile (317.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 25.27% White, 73.58% African American, 0.12% Native American, 0.16% Asian, 0.37% from other races, and 0.49% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.56% of the population.

There were 811 households, out of which 42.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 35.3% were married couples living together, 35.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 25.2% were non-families. 21.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.00 and the average family size was 3.51.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 36.6% under the age of 18, 10.1% from 18 to 24, 26.2% from 25 to 44, 16.2% from 45 to 64, and 10.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 27 years. For every 100 females, there were 82.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 71.9 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $19,167, and the median income for a family was $20,469. Males had a median income of $22,351 versus $18,693 for females. The per capita income for the city was $8,569. About 36.1% of families and 40.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 54.6% of those under age 18 and 23.0% of those age 65 or over.

Government and infrastructure[]

Drew includes some large brick buildings that serve as public housing.[8]

The United States Postal Service operates the Drew Post Office.[15]

Economy[]

At one time, Drew was the locality in the United States that had the most cotton gins. In 2008, it only had one cotton gin. Billy Turner of The Times-Picayune said "[t]here's some corn, some beans, but mostly, there's no business."[8] By 2012 the SuperValu grocery store had closed. Melanie Townsend, a woman quoted in a 2012 Bolivar Commercial article, said that since the grocery store closed, few employment opportunities were available in Drew and that the Drew School District was the largest employer in the area.[10]

Education[]

The City of Drew is served by the Sunflower County Consolidated School District. Elementary and middle school students attend schools in Drew: A. W. James Elementary School (K-5) and Drew Hunter Middle School (6-8).[16] High school students attend Ruleville Central High School in Ruleville.[17]

The North Sunflower Academy is in an unincorporated area of Sunflower County,[18] about 3 miles (4.8 km) south of Drew.[19] The school originated as a segregation academy,[20] Mississippi Delta Community College has the Drew Center in Drew.[21]

The Sunflower County Library operates the Drew Public Library.[22]

History of education[]

Previously it was served by the predominantly African-American Drew School District.[23][24] Prior to closure, the district's schools were Drew Hunter High School and A.W. James Elementary School.[25] Prior to the 2010–2011 school year the school district had three school buildings, including A.W. James Elementary School, Hunter Middle School, and Drew High School.[23] The Drew district was merged into Sunflower County schools in 2012.[17] That year Drew High School's high school division was closed. High school students began attending Ruleville Central High School.[17][26]

Prior to Federal Government Forced Integration, beginning with the 1970–1971 school year, the Drew school district had four school buildings: the predominantly and historically white Drew High School and A.W. James Elementary, and the newer African-American Hunter High School[citation needed] and the Lil’ Red Rosenwald School, which now houses a community center.[27]

The Mae Bertha Carter children were the first and only African-Americans to attend all-white schools in the county.[28] Jo Etha Collier, one of many African-Americans to attend Drew High School starting in the fall of 1970, was shot to death in 1971 at age 18.[29] As of July 1, 2012, the Drew School District was consolidated with the Sunflower County School District. Drew Hunter closed as of that date, with high school students rezoned to Ruleville Central High School.[17]

Transportation[]

Ruleville-Drew Airport is in unincorporated Sunflower County, between Drew and Ruleville.[30] The airport is jointly operated by the cities of Drew and Ruleville.[31]

Notable people[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2010) |

- Mae Bertha Carter, Civil Rights activist.[28]

- Boo Boo Davis, blues singer, released an album entitled Drew, Mississippi.[citation needed]

- Al Dixon, football player.

- Harold Dorman, rock and roll singer and songwriter.

- William Eggleston, internationally famous groundbreaking photographer, grew up in Drew.

- Willie Louis, born Willie Reed, witness to the murder of Emmett Till.[7]

- Archie Manning, former NFL quarterback.[32]

- Billy Stacy, football player.

- Pops Staples and Cleotha Staples, members of The Staple Singers.[33]

References[]

- Moye, J. Todd (2004). Let the People Decide: Black Freedom and White Resistance Movements in Sunflower County, Mississippi, 1945–1986. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-5561-4.

Tommy Johnson Blues Musician (1920s - 1930s) msbluestrail.org

Notes[]

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ Promised Land or Sandy Bayou, A compendium of early history of the town of Drew and its immediate vicinity, Written & Edited by Elizabeth A Wilson. Printed by Buford Brothers Printing, Inc. Copyright 1976. pg. 12

- ^ ""Rosenwald" film details century-old partnership for rural black education". Southern Jewish Life Magazine. Retrieved 2019-02-01.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Moye, p. 128.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Moye, p. 28.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Thompson, Wright (July 22, 2021). "His name was Emmett Till". The Atlantic. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Turner, Billy. "The hometown Archie once knew is no more." The Times-Picayune. Saturday January 26, 2009. Retrieved on March 30, 2012.

- ^ Wallace, Belinda Deneen. "The Intolerable Burden". The Journal of Negro Education (Winter (northern hemisphere) 2005 ed.). Archived from the original on June 29, 2007. Retrieved July 22, 2010.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wright, Chance. "Students protest merger." The Bolivar Commercial. April 8, 2012. Retrieved on April 12, 2012.

- ^ McGill, Ralph. "The Valid Voice." The Toledo Blade. Saturday June 15, 1963. Page 6. Retrieved from Google News (4 of 16) on March 4, 2011.

- ^ Buntin, John. "Down on Parchman Farm." Governing Magazine. July 27, 2010. Retrieved on August 13, 2010.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "Post Office Location - Drew Archived July 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine." United States Postal Service. Retrieved on February 27, 2011.

- ^ "Handbook 2012-2013." (Archive) Sunflower County School District. Retrieved on October 9, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Amy, Jeff. "Mississippi to return Okolona schools to local control; district merger ends Drew High School[permanent dead link]." Associated Press at The Republic. May 17, 2012. Retrieved on June 12, 2012.

- ^ "Home." North Sunflower Academy. Retrieved on August 10, 2010.

- ^ "Driving directions Archived 2011-07-14 at the Wayback Machine." North Sunflower Academy. Retrieved on August 10, 2010.

- ^ Moye, J. Todd. Let the People Decide: Black Freedom and White Resistance Movements in Sunflower County, Mississippi, 1945-1986. UNC Press Books, 2004. 243. Retrieved from Google Books on March 2, 2011. "Sunflower County's two other segregation academies— North Sunflower Academy, between Drew and Ruleville, and Central Delta Academy in Inverness— both sprouted in a similar fashion." ISBN 0-8078-5561-8, ISBN 978-0-8078-5561-4.

- ^ "Off Campus Centers." Mississippi Delta Community College. Retrieved on July 20, 2010.

- ^ "Sunflower County Library Directory." Sunflower County Library. Retrieved on July 21, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Drew School District Audited Financial Statements For the Year Ended June 30, 2005 Archived 2012-03-09 at the Wayback Machine." Office of the State Auditor, State of Mississippi. 12 (18/82). Retrieved on July 20, 2010.

- ^ "Schools in Drew School District." Greatschools.net. Retrieved on July 20, 2010.

- ^ "Schools Archived 2011-09-06 at the Wayback Machine." Drew School District. Retrieved on August 16, 2010.

- ^ "Home." (Archive) Drew Hunter Middle School. Retrieved on October 9, 2013. "After two successful academic years, the high school portion of the school merged with Ruleville Central High School and Drew High School became Drew Hunter Middle School."

- ^ "A Rosenwald School Archived 2012-03-26 at the Wayback Machine." Little Red Schoolhouse (William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation, University of Mississippi). Retrieved on September 11, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ravo, Nick. "Mae Bertha Carter, 76, Mother Who Defied Segregation Law." The New York Times. May 6, 1999. Retrieved on March 30, 2012.

- ^ "3 Whites Held in Slaying of Mississippi Black Girl." United Press International at the Palm Beach Post. May 26, 1971. A1. Retrieved from Google Books (74 of 190) on March 1, 2011.

- ^ FAA Airport Form 5010 for M37 PDF - Retrieved on September 23, 2010.

- ^ "Poplarville, Hattiesburg among airports receiving grants Archived 2012-02-28 at the Wayback Machine." WDAM. March 12, 2010. Retrieved on September 23, 2010.

- ^ Didinger, Ray. "NFL Notebook: Archie Manning earns Bagnell award." Comcast SportsNet Philadelphia. Sunday August 14, 2011. Retrieved on September 2, 2011. "He thought it was good fortune to be drafted by a team so close to home (Drew, Miss.)[...]"

- ^ Jon Pareles (December 22, 2000). "Pops Staples, Patriarch of the Staple Singers, Dies at 85". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

External links[]

- Cities in Mississippi

- Cities in Sunflower County, Mississippi