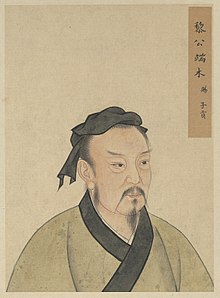

Duanmu Ci

Duanmu Ci (traditional Chinese: 端木賜; simplified Chinese: 端木赐; pinyin: Duānmù Cì; Wade–Giles: Tuan¹-mu⁴ Tzʻŭ⁴; 520–456 BC),[1] also known by his courtesy name Zigong (traditional Chinese: 子貢; simplified Chinese: 子贡; pinyin: Zǐgòng; Wade–Giles: Tzŭ³-kung⁴), was a Chinese businessman, philosopher, and politician. He was one of the most important and loyal disciples of Confucius. Among Confucius' students, he was the second best at speech, after only Zai Yu. He was a prominent diplomat of the Spring and Autumn period who served as a high official in several states, and was a very wealthy businessman.[2]

Life[]

Duanmu Ci (Zigong) was a native of the State of Wey, born in present day Xun County.[3] He was 31 years younger than Confucius.[4][5]

Zigong had mental sharpness and ability, and appears in the Analects as one of the most eloquent speakers among Confucius' students. Confucius said, "From the time that I got Ci, scholars from a distance came daily resorting to me."[4] According to Zhu Xi, Zigong was a merchant who later became wealthy through his own efforts, and developed a sense of moral self-composure through the course of his work.[6] (His past profession as a merchant is elaborated in Analects 11.18).[7]

When he first came to Confucius he quickly demonstrated an ability to grasp Confucius' basic points, and refined himself further through Confucius' education.[6] He is later revealed to have become a skillful speaker and an accomplished statesman (Analects 11.3), but Confucius may have felt that he lacked the necessary flexibility and empathy towards others necessary for achieving consummate virtue (ren): he once claimed to have achieved Confucius' moral ideal, but was then sharply dismissed by the Master (Analects 5.12); later he is criticized by Confucius for being too strict with others, and for not moderating his demands with an empathic understanding of others' limitations (Analects 14.29). He is one of the Confucius' students most commonly referred to in the Analects, also appearing in Analects 9.6, 9.13, 11.13, 13.20, 14.17, and 17.19.[7]

Duke Jing of Qi once asked Zigong how Confucius was to be ranked as a sage, and he replied, "I do not know. I have all my life had the sky over my head, but I do not know its height, and the earth under my feet, but I do not know its thickness. In my serving of Confucius, I am like a thirsty man who goes with his pitcher to the river, and there he drinks his fill, without knowing the river's depth."[4]

After studying with Confucius, Zigong became commandant of Xinyang, and Confucius gave him this advice: "In dealing with your subordinates, there is nothing like impartiality; and when wealth comes in your way, there is nothing like moderation. Hold fast these two things, and do not swerve from them. To conceal men's excellence is to obscure the worthy; and to proclaim people's wickedness is the part of a mean man. To speak evil of those whom you have not sought the opportunity to instruct is not the way of friendship and harmony."[4]

Following Confucius's death, many of the disciples built huts near their Master's grave, and mourned for him three years, but Zigong remained there, mourning alone for three years more.[4]

According to Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian, Duanmu Ci later served as Prime Minister for both the states of Lu and Wey, but this account could not be confirmed with other ancient chronicles. He finally died in the state of Qi.[8]

Zigong saved the state of Lu (子貢救魯)[9][]

Tian Chang (田常), prime minister of the state of Qi (齊) was to attack the state of Lu (魯), home state of Confucius. Confucius wisely chose Zigong among his disciples for the mission of saving the state of Lu.

Zigong first went to Qi to meet with Tian Chang and said, "The state of Lu has weak army and impaired fortress, Qi will surely win the battle against Lu, and the military leaders will gain prestige, challenging the power of yours. I suggest you attack the state of Wu (吴) instead, who has strong army and impenetrable fortress, military leaders will be defeated and yielding more power to you." Tian Chang loved the idea, but struggled to find excuses to shift target, hence Zigong promised to persuade the King of Wu to attack Qi instead.

Fuchai (夫差), King of Wu was belligerent and aspired a victory over powerful Qi, but he was concerned that the neighboring state of Yue (越) might be planning a revenge against him for a previous disgraceful defeat. Zigong appealed to his arrogant nature by emphasizing the legacy winning Qi could bring. He also appeased him by convincing the King of Yue to show more obedience.

Zigong said to Goujian (句踐) the King of Yue, "This is your once in a lifetime opportunity to revenge yourself. Qi and Wu both have strong military power, and their battle will surely weaken both of them deeply. You need to relieve the concern of Fuchai so that he will wage the war against Qi". Goujian thought this is the best advice, and gifted Fuchai with fine armors and well trained soldiers, and even offered to help the battle personally. Fuchai thus went to attack Qi.

Finally, Zigong went to the state of Jin (晉) to warn the King of Jin a possible attack from Wu in the event that Fuchai defeated Qi and believed himself undefeatable.

The chain of events after Zigong's manipulation: Qi lost the battle to Wu, resulting in Tian Chang gaining much more power within Qi; Fuchai indeed went on to attack Jin and was defeated by the well prepared Jin army; Goujian attacked Wu while Fuchai was on the way back from Jin and gained control of Wu. Zigong not only saved the state of Lu, but changed the fate of all five states involved.

Honours[]

In Confucian temples, Duanmu Ci's spirit tablet is placed the third among the Twelve Wise Ones, on the east.[4]

During the Tang dynasty, Emperor Xuanzong posthumously awarded Duanmu Ci the nobility title of Marquis of Li (黎侯). During the Song dynasty, he was further awarded the titles of Duke of Liyang (黎陽公) and Duke of Li (黎公).[10]

Duanmu Ci's offspring held the title of Wujing Boshi (五經博士; Wǔjīng Bóshì).[11]

Notes[]

- ^ Taylor & Choy 2005, p. 643–4.

- ^ Confucius 1997, p. 202.

- ^ "浚县概况". www.xunxian.gov.cn. Retrieved 2021-05-19.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Legge 2009, p. 115–6.

- ^ Han 2010, pp. 4587.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Slingerland 2003, p. 7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Slingerland 2003, p. 40.

- ^ Han 2010, pp. 4602–3.

- ^ Qian, Sima. Records of the Grand Historian. pp. Volume 67: Biographies of the disciples of Zhongni.

- ^ Wu Xiaoyun. "Duanmu Ci" (in Chinese). Taipei Confucian Temple. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ^ H.S. Brunnert; V.V. Hagelstrom (15 April 2013). Present Day Political Organization of China. Routledge. pp. 494–. ISBN 978-1-135-79795-9.

Bibliography[]

- Confucius (1997). The Analects of Confucius. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506157-4.

- Han, Zhaoqi (2010). "Biographies of the Disciples of Confucius". Shiji (史记) (in Chinese). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. ISBN 978-7-101-07272-3.

- Legge, James (2009). The Confucian Analects, the Great Learning & the Doctrine of the Mean. Cosimo. ISBN 978-1-60520-644-8.

- Slingerland, Edward (2003). Analects: With Selections from Traditional Commentaries. Hackett Publishing. ISBN 1-60384-345-0.

- Taylor, Rodney Leon; Choy, Howard Yuen Fung (2005). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Confucianism: N–Z. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8239-4081-3.

- 520 BC births

- 456 BC deaths

- 6th-century BC Chinese people

- 6th-century BC Chinese philosophers

- 5th-century BC Chinese people

- 5th-century BC Chinese philosophers

- Disciples of Confucius

- Wey (state)

- Zhou dynasty philosophers