Dzongkha

| Dzongkha | |

|---|---|

| Bhutanese | |

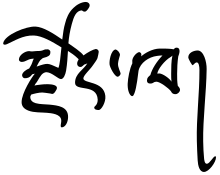

| རྫོང་ཁ་ | |

| |

| Native to | Bhutan |

| Ethnicity | Bhutanese |

Native speakers | 171,080 (2013)[1] Total speakers: 640,000[2] |

Early forms | Proto-Sino-Tibetan

|

| Dialects | |

| Tibetan script Dzongkha Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Dzongkha Development Commission |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | dz |

| ISO 639-2 | dzo |

| ISO 639-3 | dzo – inclusive codeIndividual codes: lya – Layaluk – Lunanaadp – Adap |

| Glottolog | nucl1307 |

| Linguasphere | 70-AAA-bf |

Districts of Bhutan in which the Dzongkha language is spoken natively are highlighted in yellow. | |

Dzongkha (རྫོང་ཁ་, [dzòŋkʰɑ́]) is a Sino-Tibetan language spoken by over half a million people in Bhutan; it is the country's sole official and national language.[3] The Tibetan script is used to write Dzongkha.

The word dzongkha means "the language of the palace"; dzong means "palace" and kha is language. As of 2013, Dzongkha had 171,080 native speakers and about 640,000 total speakers.[2]

Usage[]

Dzongkha and its dialects are the native tongue of eight western districts of Bhutan (viz. Wangdue Phodrang, Punakha, Thimphu, Gasa, Paro, Ha, Dagana and Chukha).[4] There are also some native speakers near the Indian town of Kalimpong, once part of Bhutan but now in North Bengal.

Dzongkha was declared the national language of Bhutan in 1971.[5] Dzongkha study is mandatory in all schools, and the language is the lingua franca in the districts to the south and east where it is not the mother tongue. The 2003 Bhutanese film Travellers and Magicians is in Dzongkha.

Writing system[]

The Tibetan script used to write Dzongkha has thirty basic letters, sometimes known as "radicals", for consonants. Dzongkha is usually written in Bhutanese forms of the Uchen script, forms of the Tibetan script known as Jôyi "cursive longhand" and Jôtshum "formal longhand". The print form is known simply as Tshûm.[6]

Romanization[]

There are various systems of romanization and transliteration for Dzongkha, but none accurately represents its phonetic sound.[7] The Bhutanese government adopted a transcription system known as Roman Dzongkha, devised by the linguist George van Driem, as its standard in 1991.[5]

Phonology[]

Tones[]

Dzongkha is a tone language and has two register tones: high and low.[8] The tone of a syllable determines the allophone of the onset and the phonation type of the nuclear vowel.[9]

Consonants[]

| Bilabial | Dental/ alveolar |

Retroflex/ palatal |

Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||

| Stop | plain | p | t | ʈ | k | |

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | ʈʰ | kʰ | ||

| Affricate | plain | ts | tɕ | |||

| aspirated | tsʰ | tɕʰ | ||||

| Sibilant | s | ɕ | ||||

| Rhotic | r | |||||

| Continuant | ɬ l | j | w | h | ||

All consonants may begin a syllable. In the onsets of low-tone syllables, consonants are voiced.[9] Aspirated consonants (indicated by the superscript h), /ɬ/, and /h/ are not found in low-tone syllables.[9] The rhotic /r/ is usually a trill [r] or a fricative trill [r̝],[8] and is voiceless in the onsets of high-tone syllables.[9]

/t, tʰ, ts, tsʰ, s/ are dental.[8] Descriptions of the palatal affricates and fricatives vary from alveolo-palatal to plain palatal.[8][10][9]

Only a few consonants are found in syllable-final positions. Most common among them are /m, n, p/.[9] Syllable-final /ŋ/ is often elided and results in the preceding vowel nasalized and prolonged, especially word-finally.[11][9] Syllable-final /k/ is most often omitted when word-final as well, unless in formal speech.[9] In literary pronunciation, liquids /r/ and /l/ may also end a syllable.[8] Though rare, /ɕ/ is also found in syllable-final positions.[8][9] No other consonants are found in syllable-final positions.

Vowels[]

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː yː | u uː |

| Mid | e eː øː | o oː |

| Open | ɛː | ɑ ɑː |

- When in low tone, vowels are produced with breathy voice.[8][11]

- In closed syllables, /i/ varies between [i] and [ɪ], the latter being more common.[8][9]

- /yː/ varies between [yː] and [ʏː].[8]

- /e/ varies between close-mid [e] and open-mid [ɛ], the latter being common in closed syllables. /eː/ is close-mid [eː]. /eː/ may not be longer than /e/ at all, and differs from /e/ more often in quality than in length.[8]

- Descriptions of /øː/ vary between close-mid [øː] and open-mid [œː].[8][9]

- /o/ is close-mid [o], but may approach open-mid [ɔ] especially in closed syllables. /oː/ is close-mid [oː].[8]

- /ɛː/ is slightly lower than open-mid, i.e. [ɛ̞ː].[8]

- /ɑ/ may approach [ɐ], especially in closed syllables.[8][9]

- When nasalized or followed by [ŋ], vowels are always long.[11][9]

Phonotactics[]

Many words in Dzongkha are monosyllabic.[9] Syllables usually take the form of CVC, CV, or VC.[9] Syllables with complex onsets are also found, but such an onset must be a combination of an unaspirated bilabial stop and a palatal affricate.[9] The bilabial stops in complex onsets are often omitted in colloquial speech.[9]

[]

Dzongkha is considered a South Tibetic language. It is closely related to and partially intelligible with Sikkimese, and to some other Bhutanese languages such as Chocangaca, Brokpa, Brokkat and Lakha.

Dzongkha bears a close linguistic relationship to J'umowa, which is spoken in the Chumbi Valley of Southern Tibet.[12] It has a much more distant relationship to Standard Tibetan. Although spoken Dzongkha and Tibetan are largely mutually unintelligible, the literary forms of both are both highly influenced by the liturgical (clerical) Classical Tibetan language, known in Bhutan as Chöke, which has been used for centuries by Buddhist monks. Chöke was used as the language of education in Bhutan until the early 1960s when it was replaced by Dzongkha in public schools.[13]

Although descended from Classical Tibetan, Dzongkha shows a great many irregularities in sound changes that make the official spelling and standard pronunciation more distant from each other than is the case with Standard Tibetan. "Traditional orthography and modern phonology are two distinct systems operating by a distinct set of rules."[14]

Sample text[]

The following is a sample text in Dzongkha of Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

འགྲོ་

’Gro-

བ་

ba-

མི་

mi-

རིགས་

rigs-

ག་

ga-

ར་

ra-

དབང་

dbaṅ-

ཆ་

cha-

འདྲ་

’dra-

མཏམ་

mtam-

འབད་

’bad-

སྒྱེཝ་

sgyew-

ལས་

las-

ག་

ga-

ར་

ra-

གིས་

gis-

གཅིག་

gcig-

གིས་

gis-

གཅིག་

gcig-

ལུ་

lu-

སྤུན་

spun-

ཆའི་

cha’i-

དམ་

dam-

ཚིག་

tshig-

བསྟན་

bstan-

དགོ།

dgo

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.[15]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Dzongkha at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Laya at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Lunana at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Adap at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) - ^ Jump up to: a b "How many people speak Dzongkha?". languagecomparison.com. Retrieved 2018-03-15.

- ^ "Constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan. Art. 1, § 8" (PDF). Government of Bhutan. 2008-07-18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

- ^ van Driem, George; Tshering of Gaselô, Karma (1998). Dzongkha. Languages of the Greater Himalayan Region. I. Leiden, The Netherlands: Research CNWS, School of Asian, African, and Amerindian Studies, Leiden University. p. 3. ISBN 90-5789-002-X.

- ^ Jump up to: a b van Driem (1991)

- ^ Driem, George van (1998). Dzongkha = Rdoṅ-kha. Leiden: Research School, CNWS. p. 47. ISBN 90-5789-002-X.

- ^ See for instance Report on the current status of the United Nations romanization systems for geographical names: Tibetan Report on the current status of the United Nations romanization systems for geographical names: Dzongkha

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n van Driem (1992).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Downs (2011).

- ^ Michailovsky & Mazaudon (1989).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c van Driem (1994).

- ^ van Driem, George (2007). "Endangered Languages of Bhutan and Sikkim: South Bodish Languages". In Moseley, Christopher (ed.). Encyclopedia of the World's Endangered Languages. Routledge. p. 294. ISBN 978-0-7007-1197-0.

- ^ van Driem, George; Tshering of Gaselô, Karma (1998). Dzongkha. Languages of the Greater Himalayan Region. I. Leiden, The Netherlands: Research CNWS, School of Asian, African, and Amerindian Studies, Leiden University. pp. 7–8. ISBN 90-5789-002-X.

- ^ Driem, George van (1998). Dzongkha = Rdoṅ-kha. Leiden: Research School, CNWS. p. 110. ISBN 90-5789-002-X.

Traditional orthography and modern phonology are two distinct systems operating by a distinct set of rules.

- ^ "Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 1) in Sino-Tibetan languages". omniglot.com.

Bibliography[]

- Downs, Cheryl Lynn (2011). Issues in Dzongkha Phonology: An Optimality Theoretic Approach (PDF) (Master's thesis). San Diego State University.

- Dzongkha Development Commission (2009). Rigpai Lodap: An Intermediate Dzongkha-English Dictionary (འབྲིང་རིམ་རྫོང་ཁ་ཨིང་ལིཤ་ཚིག་མཛོད་རིག་པའི་ལོ་འདབ།) (PDF). Thimphu: Dzongkha Development Commission. ISBN 978-99936-765-3-9.[permanent dead link]

- Dzongkha Development Commission (2009). Kartshok Threngwa: A Book on Dzongkha Synonyms & Antonyms (རྫོང་ཁའི་མིང་ཚིག་རྣམ་གྲངས་དང་འགལ་མིང་སྐར་ཚོགས་ཕྲེང་བ།) (PDF). Thimphu: Dzongkha Development Commission. ISBN 99936-663-13-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-11-17. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- Dzongkha Development Commission (1999). The New Dzongkha Grammar (rdzong kha'i brda gzhung gsar pa). Thimphu: Dzongkha Development Commission.

- Dzongkha Development Commission (1990). Dzongkha Rabsel Lamzang (rdzong kha rab gsal lam bzang). Thimphu: Dzongkha Development Commission.

- Dzongkha Development Authority (2005). English-Dzongkha Dictionary (ཨིང་ལིཤ་རྫོང་ཁ་ཤན་སྦྱར་ཚིག་མཛོད།). Thimphu: Dzongkha Development Authority, Ministry of Education.

- Imaeda, Yoshiro (1990). Manual of Spoken Dzongkha in Roman Transcription. Thimphu: Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers (JOCV), Bhutan Coordinator Office.

- Lee, Seunghun J.; Kawahara, Shigeto (2018). "The phonetic structure of Dzongkha: a preliminary study". Journal of the Phonetic Society of Japan. 22 (1): 13–20. doi:10.24467/onseikenkyu.22.1_13.

- Mazaudon, Martine. 1985. “Dzongkha Number Systems.” S. Ratanakul, D. Thomas & S. Premsirat (eds.). Southeast Asian Linguistic Studies presented to André-G. Haudricourt. Bangkok: Mahidol University. 124–57

- Mazaudon, Martine; Michailovsky, Boyd (1986), Syllabicity and suprasegmentals: the Dzongkha monosyllabic noun

- Michailovsky, Boyd; Mazaudon, Martine (1989). "Lost syllables and tone contour in Dzongkha (Bhutan)". In Bradley, David; Henderson, E. J. A.; Mazaudon, Martine (eds.). Prosodic Analysis and Asian Linguistics: To Honour R.K. Sprigg. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. pp. 115–136. hdl:1885/145648.

- Michailovsky, Boyd (1989). "Notes on Dzongkha orthography". In Bradley, David; Henderson, E. J. A.; Mazaudon, Martine (eds.). Prosodic Analysis and Asian Linguistics: To Honour R.K. Sprigg. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. pp. 297–301. hdl:1885/145648.

- Tournadre, Nicolas (1996). "Comparaison des systèmes médiatifs de quatre dialectes tibétains (tibétain central, ladakhi, dzongkha et amdo)". In Guentchéva, Z. (ed.). L'énonciation médiatisée (PDF). Bibliothèque de l’Information Grammaticale, 34 (in French). Louvain Paris: Peeters. pp. 195–214. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-10-19.

- van Driem, George (1991). Guide to Official Dzongkha Romanization (PDF). Thimphu, Bhutan: Dzongkha Development Commission (DDC). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-23.

- van Driem, George (1992). The Grammar of Dzongkha (PDF). Thimphu, Bhutan: RGoB, Dzongkha Development Commission (DDC).

- van Driem, George (1993). Language policy in Bhutan. SOAS, London. Archived from the original on 2018-09-11.

- van Driem, George (1994). "The Phonologies of Dzongkha and the Bhutanese Liturgical Language" (PDF). Zentralasiatische Studien (24): 36–44.

- van Driem, George (2007). "Endangered Languages of Bhutan and Sikkim: South Bodish Languages". In Moseley, Christopher (ed.). Encyclopedia of the World's Endangered Languages. Routledge. pp. 294–295. ISBN 978-0-7007-1197-0.

- van Driem, George (n.d.). The First Linguistic Survey of Bhutan. Thimphu, Bhutan: Dzongkha Development Commission (DDC).

- Watters, Stephen A. (1996). A preliminary study of prosody in Dzongkha (Masters thesis). Arlington: UT at Arlington.

- Watters, Stephen A. (2018). A grammar of Dzongkha (dzo): phonology, words, and simple clauses (Doctor of Philosophy thesis). Rice University. hdl:1911/103233.

- van Driem, George; Karma Tshering of Gaselô (collab) (1998). Dzongkha. Languages of the Greater Himalayan Region. Leiden: Research School CNWS, School of Asian, African, and Amerindian Studies. ISBN 90-5789-002-X. - A language textbook with three audio compact disks.

- Karma Tshering; Van Driem, George (2019) [1992]. The Grammar of Dzongkha (3rd ed.). Santa Barbara: Himalayan Linguistics. doi:10.5070/H918144245. ISBN 978-0-578-50750-7.

External links[]

| Dzongkha edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dzongkha language. |

| Wikivoyage has a phrasebook for Dzongkha. |

- Bhutanese literatures

- Dzongkha Development Commission Thimphu, Bhutan

- Dzongkha-English Dictionary

- Dzongkha podcast

- Dzongkha Romanization for Geographical Names

- Free textbooks and dictionaries published by the Dzongkha Development Commission

- Bhutan National Policy and Strategy for Development and Promotion of Dzongkha

- Dzongkha Unicode – site The National Library of Bhutan (en – dz)

Vocabulary[]

- Online searchable dictionary (Dz-En, En-Dz, Dz-Dz) or Online Dzongkha-English Dictionary – site Dzongkha Development Commission (en – dz)

- Dzongkha Computer Terms(pdf)

- English-Dzongkha Pocket Dictionary(pdf)

- Rigpai Lodap: An Intermediate Dzongkha-English Dictionary(pdf)

- Kartshok Threngwa: A Book on Dzongkha Synonyms & Antonyms(pdf)

- Names of Countries and Capitals in Dzongkha(pdf)

- A Guide to Dzongkha-Translation(pdf)

Grammar[]

- A colloquial grammar of the Bhutanese language. by Byrne, St. Quintin. Allahabad: Pioneer Press, 1909

- Dzongkha transliteration – site National Library of Bhutan (en – dz)

- Dzongkha, The National Language of Bhutan – site Dzongkha Linux (en – dz)

- Romanization of Dzongkha

- Dzongkha : Origin and Description

- Dzongkha language, alphabet and pronunciation

- Dzongkha in Wikipedia: Русский, Français, 日本語, Eesti, English

- Pioneering Dzongkha Text To Speech Synthesis(pdf)

- Dzongkha Grammar & other materials – site The Dzongkha Development Commission (en – dz)

- Коряков Ю.Б. Практическая транскрипция для языка дзонг-кэ

- Classical Tibetan-Dzongkha Dictionary(pdf)

- Dzongkha language

- Languages of Bhutan

- Languages written in Tibetan script