Early Modern English

| Early Modern English | |

|---|---|

| Shakespeare's English, King James English | |

| English | |

William Shakespeare's Sonnet 132 in the 1609 Quarto | |

| Region | England, Southern Scotland, Ireland, Wales and British colonies |

| Era | developed into Modern English in the late 17th century |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | Proto-Indo-European

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| ISO 639-6 | emen |

| Glottolog | None |

| IETF | en-emodeng |

Early Modern English or Early New English (sometimes abbreviated EModE,[1] EMnE, or EME) is the stage of the English language from the beginning of the Tudor period to the English Interregnum and Restoration, or from the transition from Middle English, in the late 15th century, to the transition to Modern English, in the mid-to-late 17th century.[2]

Before and after the accession of James I to the English throne in 1603, the emerging English standard began to influence the spoken and written Middle Scots of Scotland.

The grammatical and orthographical conventions of literary English in the late 16th century and the 17th century are still very influential on modern Standard English. Most modern readers of English can understand texts written in the late phase of Early Modern English, such as the King James Bible and the works of William Shakespeare, and they have greatly influenced Modern English.

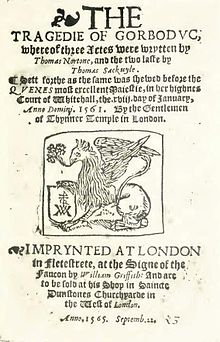

Texts from the earlier phase of Early Modern English, such as the late-15th century Le Morte d'Arthur (1485) and the mid-16th century Gorboduc (1561), may present more difficulties but are still obviously closer to Modern English grammar, lexicon, and phonology than are 14th-century Middle English texts, such as the works of Geoffrey Chaucer.

History[]

English Renaissance[]

Transition from Middle English[]

The change from Middle English to Early Modern English was not just a matter of changes of vocabulary or pronunciation; a new era in the history of English was beginning.

An era of linguistic change in a language with large variations in dialect was replaced by a new era of a more standardised language, with a richer lexicon and an established (and lasting) literature.

- 1476 – William Caxton starts printing in Westminster; however, the language that he uses reflects the variety of styles and dialects used by the authors who originally wrote the material.

Tudor period (1485–1603)[]

- 1485 – Caxton publishes Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur, the first print bestseller in English. Malory's language, while archaic in some respects, is clearly Early Modern and is possibly a Yorkshire or Midlands dialect.

- 1491 or 1492 – Richard Pynson starts printing in London; his style tends to prefer Chancery Standard, the form of English used by the government.

Henry VIII[]

- c. 1509 – Pynson becomes the King's official printer.

- From 1525 – Publication of William Tyndale's Bible translation, which was initially banned.

- 1539 – Publication of the Great Bible, the first officially-authorised Bible in English. Edited by Myles Coverdale, it is largely from the work of Tyndale. It is read to congregations regularly in churches, which familiarises much of the population of England with a standard form of the language.

- 1549 – Publication of the first Book of Common Prayer in English, under the supervision of Thomas Cranmer (revised 1552 and 1662), which standardises much of the wording of church services. Some have argued that since attendance at prayer book services was required by law for many years, the repetitive use of its language helped to standardise Modern English even more than the King James Bible (1611) did.[3]

- 1557 – Publication of Tottel's Miscellany.

Elizabethan English[]

- Elizabethan era (1558–1603)

- 1582 – The Rheims and Douai Bible is completed, and the New Testament is released in Rheims, France, in 1582. It is the first complete English translation of the Bible that is officially sponsored and carried out by the Catholic Church (earlier translations into English, especially of the Psalms and Gospels existed as far back as the 9th century, but it is the first Catholic English translation of the full Bible). Though the Old Testament is ready complete, it is not published until 1609–1610, when it is released in two volumes. While it does not make a large impact on the English language at large, it certainly plays a role in the development of English, especially in the world's heavily-Catholic English-speaking areas.

- Christopher Marlowe, fl. 1586–1593

- 1592 – The Spanish Tragedy by Thomas Kyd

- c. 1590 to c. 1612 – Shakespeare's plays written.

17th century[]

Jacobean and Caroline eras[]

Jacobean era (1603–1625)[]

- 1609 – Shakespeare's sonnets published

- Other playwrights:

- 1607 – The first successful permanent English colony in the New World, Jamestown, is established in Virginia. Early vocabulary specific to American English comes from indigenous languages (such as moose, racoon).

- 1611 – The King James Version is published, largely based on Tyndale's translation. It remains the standard Bible in the Church of England for many years.[clarification needed]

- 1623 – Shakespeare's First Folio published

Caroline era and English Civil War (1625–1649)[]

- 1630–1651 – William Bradford, Governor of Plymouth Colony, writes in his journal. It will become Of Plymouth Plantation, one of the earliest texts written in the American Colonies.

- 1647 – Publication of the first Beaumont and Fletcher folio.

Interregnum and Restoration[]

The English Civil War and the Interregnum were times of social and political upheaval and instability. The dates for Restoration literature are a matter of convention and differ markedly from genre to genre. In drama, the "Restoration" may last until 1700, but in poetry, it may last only until 1666, the annus mirabilis (year of wonders), and prose, it last until 1688, with the increasing tensions over succession and the corresponding rise in journalism and periodicals, or until 1700, when those periodicals grew more stabilised.

- 1651 – Publication of Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes.

- 1660–1669 – Samuel Pepys writes in his diary, which will become an important eyewitness account of the Restoration Era.

- 1662 – New edition of the Book of Common Prayer, largely based on the 1549 and subsequent editions, which long remains a standard work in English.

- 1667 – Publication of Paradise Lost by John Milton and of Annus Mirabilis by John Dryden.

Development to Modern English[]

The 17th-century port towns and their forms of speech gain influence over the old county towns. From around the 1690s onwards, England experienced a new period of internal peace and relative stability, which encouraged the arts including literature.

Modern English can be taken to have emerged fully by the beginning of the Georgian era in 1714, but English orthography remained somewhat fluid until the publication of Johnson's A Dictionary of the English Language, in 1755.

The towering importance of William Shakespeare over the other Elizabethan authors was the result of his reception during the 17th and the 18th centuries, which directly contributes to the development of Standard English.[citation needed] Shakespeare's plays are therefore still familiar and comprehensible 400 years after they were written,[4] but the works of Geoffrey Chaucer and William Langland, which had been written only 200 years earlier, are considerably more difficult for the average modern reader.

Orthography[]

The orthography of Early Modern English was fairly similar to that of today, but spelling was unstable. Early Modern English, as well as Modern English, inherited orthographical conventions predating the Great Vowel Shift.

Early Modern English spelling was similar to Middle English orthography. Certain changes were made, however, sometimes for reasons of etymology (as with the silent ⟨b⟩ that was added to words like debt, doubt and subtle).

Early Modern English orthography had a number of features of spelling that have not been retained:

- The letter ⟨S⟩ had two distinct lowercase forms: ⟨s⟩ (short s), as is still used today, and ⟨ſ⟩ (long s). The short s was always used at the end of a word and often elsewhere. The long s, if used, could appear anywhere except at the end of a word. The double lowercase S was written variously ⟨ſſ⟩, ⟨ſs⟩ or ⟨ß⟩ (the last ligature is still used in German ß).[5] That is similar to the alternation between medial (σ) and final lower case sigma (ς) in Greek.

- ⟨u⟩ and ⟨v⟩ were not considered two distinct letters then but as still different forms of the same letter. Typographically, ⟨v⟩ was frequent at the start of a word and ⟨u⟩ elsewhere:[6] hence vnmoued (for modern unmoved) and loue (for love). The modern convention of using ⟨u⟩ for the vowel sounds and ⟨v⟩ for the consonant appears to have been introduced in the 1630s.[7] Also, ⟨w⟩ was frequently represented by ⟨vv⟩.

- Similarly, ⟨i⟩ and ⟨j⟩ were also still considered not as two distinct letters, but as different forms of the same letter: hence ioy for joy and iust for just. Again, the custom of using ⟨i⟩ as a vowel and ⟨j⟩ as a consonant began in the 1630s.[7]

- The letter ⟨þ⟩ (thorn) was still in use during the Early Modern English period but was increasingly limited to handwritten texts. In Early Modern English printing, ⟨þ⟩ was represented by the Latin ⟨Y⟩ (see Ye olde), which appeared similar to thorn in blackletter typeface ⟨