Emergency management

The lead section of this article may need to be rewritten. (April 2020) |

Emergency management is the organization and management of the resources and responsibilities for dealing with all humanitarian aspects of emergencies (preparedness, response, mitigation, and recovery). The aim is to reduce the harmful effects of all hazards, including disasters.

The World Health Organization defines an emergency as the state in which normal procedures are interrupted, and immediate measures (management) need to be taken to prevent it from becoming a disaster, which is even harder to recover from. Disaster management is a related term but should not be equated to emergency management.[citation needed]

Emergency planning ideals[]

Emergency planning is a discipline of urban planning and design; it aims to prevent emergencies from occurring, and failing that, initiates an efficient action plan to mitigate the results and effects of any emergencies. The development of emergency plans is a cyclical process, common to many risk management disciplines such as business continuity and security risk management:

- Recognition or identification of risks[1]

- Ranking or evaluation of risks[2]

- Responding to significant risks

- Tolerating

- Treating

- Transferring

- Terminating

- Resourcing controls and planning

- Reaction planning

- Reporting and monitoring risk performance

- Reviewing the risk management framework

There are a number of guidelines and publications regarding emergency planning, published by professional organizations such as ASIS, National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), and the International Association of Emergency Managers (IAEM).

Health and safety of workers[]

hideThis section has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Cleanup during disaster recovery involves many occupational hazards. Often, these hazards are exacerbated by the conditions of the local environment as a result of the natural disaster.[3] Employers are responsible for minimizing exposure to these hazards and protecting workers when possible, including identification and thorough assessment of potential hazards, application of appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), and the distribution of other relevant information in order to enable safe performance of work.[4]

Physical exposures[]

Flood-associated injuries

Flooding disasters often expose workers to trauma from sharp and blunt objects hidden under murky waters that cause lacerations and open and closed fractures. These injuries are further exacerbated with exposure to the often contaminated waters, leading to increased risk for infection.[5] The risk of hypothermia significantly increases with prolonged exposure to water temperatures less than 75 degrees Fahrenheit.[6] Non-infectious skin conditions may also occur including miliaria, immersion foot syndrome (including trench foot), and contact dermatitis.[5]

Earthquake-associated injuries

The predominant injuries are related to building structural components, including falling debris with possible crush injury, burns, electric shock, and being trapped under rubble.[7]

Chemical exposures[]

Hazardous material release[]

Chemicals can pose a risk to human health when exposed to humans at certain quantities. After a natural disaster, certain chemicals can become more prominent in the environment. These hazardous materials can be released directly or indirectly. Chemical hazards directly released after a natural disaster often occur at the same time as the event, impeding planned actions for mitigation. Indirect release of hazardous chemicals can be intentionally released or unintentionally released. An example of intentional release is insecticides used after a flood or chlorine treatment of water after a flood. These chemicals can be controlled through engineering to minimize their release when a natural disaster strikes; for example, agrochemicals from inundated storehouses or manufacturing facilities poisoning the floodwaters or asbestos fibers released from a building collapse during a hurricane.[8] The flowchart to the right has been adopted from research performed by Stacy Young et al.[8]

Exposure limits

Below are TLV-TWA, PEL, and IDLH values for common chemicals workers are exposed to after a natural disaster.[9][10]

| Chemical | TLV-TWA (mg/m3) | PEL (mg/m3) | IDLH (mg/m3) |

| Magnesium | 10 | 15 | 750 |

| Phosphorus | 0.1 | 0.1 | Not established |

| Ammonia | 17 | 35 | 27 |

| Silica(R) | .025 | 10 | 50 |

| Chlorine dioxide | 0.28 | 0.3 | 29 |

| Asbestos | 10 (fibers/m^3) | 10 (fibers/m^3) | Not established |

Direct release

- Magnesium

- Phosphorus

- Ammonia

- Silica

Intentional release

- Insecticides

- Chlorine dioxide

Unintentional release

- Crude oil components

- Benzene, N-hexane, hydrogen sulfide, cumene, ethylbenzene, naphthalene, toluene, xylenes, PCBs, agrochemicals

- Asbestos

Biological exposures[]

Mold exposures: Exposure to mold is commonly seen after a natural disaster such as flooding, hurricane, tornado or tsunami. Mold growth can occur on both the exterior and interior of residential or commercial buildings. Warm and humid conditions encourage mold growth.[11] While the exact number of mold species is unknown, some examples of commonly found indoor molds are Aspergillus, Cladosporium, Alternaria and Penicillium. Reaction to molds differ between individuals and can range from mild symptoms such as eye irritation, cough to severe life-threatening asthmatic or allergic reactions. People with history of chronic lung disease, asthma, allergy, other breathing problems or those that are immunocompromised could be more sensitive to molds and may develop fungal pneumonia.

Some methods to prevent mold growth after a natural disaster include opening all doors and windows, using fans to dry out the building, positioning fans to blow air out of the windows, cleaning up the building within the first 24–48 hours, and moisture control.[12] When removing molds, N-95 masks or respirators with a higher protection level should be used to prevent inhalation of molds into the respiratory system.[13] Molds can be removed from hard surfaces by soap and water, a diluted bleach solution[14] or commercial products.

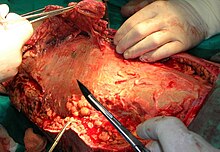

Human remains: According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), "There is no direct risk of contagion or infectious disease from being near human remains for people who are not directly involved in recovery or other efforts that require handling dead bodies.”[15] Most viruses and bacteria perish along with the human body after death.[16] Therefore, no excessive measures are necessary when handling human remains indirectly. However, for workers in direct contact with human remains, universal precautions should be exercised in order to prevent unnecessary exposure to blood-borne viruses and bacteria. Relevant PPE includes eye protection, face mask or shield, and gloves. The predominant health risk are gastrointestinal infections through fecal-oral contamination, so hand hygiene is paramount to prevention. Mental health support should also be available to workers who endure psychological stress during and after recovery.[17]

Flood-associated skin infections: Flood waters are often contaminated with bacteria and waste and chemicals. Prolonged, direct contact with these waters leads to an increased risk for skin infection, especially with open wounds in the skin or history of a previous skin condition, such as atopic dermatitis or psoriasis. These infections are exacerbated with a compromised immune system or an aging population.[5] The most common bacterial skin infections are usually with Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. One of the most uncommon, but well-known bacterial infections is from Vibrio vulnificus, which causes a rare, but often fatal infection called necrotizing fasciitis.

Other salt-water Mycobacterium infections include the slow growing M. marinum and fast growing M. fortuitum, M. chelonae, and M. abscessus. Fresh-water bacterial infections include Aeromonas hydrophila, Burkholderia pseudomallei causing melioidosis, leptospira interrogans causing leptospirosis, and chromobacterium violaceum. Fungal infections may lead to chromoblastomycosis, blastomycosis, mucormycosis, and dermatophytosis. Numerous other arthropod, protozoal, and parasitic infections have been described.[5] A worker can reduce the risk of flood-associated skin infections by avoiding the water if an open wound is present, or at minimum, cover the open wound with a waterproof bandage. Should contact with flood water occur, the open wound should be washed thoroughly with soap and clean water.[18]

Psychosocial exposures[]

According to the CDC, "Sources of stress for emergency responders may include witnessing human suffering, risk of personal harm, intense workloads, life-and-death decisions, and separation from family."[19] Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) provides stress prevention and management resources for disaster recovery responders.[20]

Volunteer responsibilities[]

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) advises those who desire to assist go through organized volunteer organizations and not to self-deploy to affected locations. The National Volunteer Organizations Active in Disaster (VOAD) serves as the primary point of contact for volunteer organization coordination. All states have their own state VOAD organization.[21]

Employer responsibilities[]

Every employer is required to maintain a safe and healthy workplace for their employees. When an emergency situation occurs, employers are expected to protect workers from all harm resulting from any potential hazard, including physical, chemical, and biological exposure. In addition, an employer should provide pre-emergency training and build an emergency action plan.[22]

Emergency action plan (EAP)[]

The EAP is a written document about what actions employers and employees should take when responding to an emergency situation. According to OSHA regulations 1910.38,[23] an employer must have an emergency action plan whenever an OSHA standard requires one. To develop an EAP, an employer should start from workplace evaluation. Occupational emergency management can be divided into worksite evaluation, exposure monitoring, hazard control, work practices, and training.

Worksite evaluation is about identifying the source and location of the potential hazards such as falling, noise, cold, heat, hypoxia, infectious materials, and toxic chemicals that each of the workers may encounter during emergency situations.

Hazard control[]

Employers can conduct hazard control by:

- Elimination or substitution: Eliminating the hazard from the workplace.

- Engineering controls

- Work practice or administrative controls: Change how the task was performed to reduce the probability of exposure.

- Personal protective equipment

Training[]

Employers should train their employees annually before an emergency action plan is implemented to inform employees of their responsibilities and/or plan of action during emergency situations.[24] The training program should include the types of emergencies that may occur, the appropriate response, evacuation procedure, warning/reporting procedure, and shutdown procedures. Training requirements are different depending on the size of workplace and workforce, processes used, materials handled, available resources and who will be in charge during an emergency.

The training program should address the following information:

- Workers' roles and responsibilities.

- Potential hazards and hazard-preventing actions.

- Notification alarm system, and communications process.[25]

- Communication means between family members in an emergency.

- First aid kits.

- Emergency response procedures.

- Evacuation procedures.

- A list of emergency equipment including its location and function.

- Emergency shutdown procedures.

After the emergency action plan is completed, the employer and employees should review the plan carefully and post it in a public area that is accessible to everyone. In addition, another responsibility of the employer is to keep a record of any injury or illness of workers according to OSHA/State Plan Record-keeping regulations.[26]

Implementation ideals[]

This section does not cite any sources. (April 2020) |

This section is written like a manual or guidebook. (May 2020) |

Pre-incident training and testing[]

Emergency management plans and procedures should include the identification of appropriately trained staff members responsible for decision-making when an emergency occurs. Training plans should include internal people, contractors and civil protection partners, and should state the nature and frequency of training and testing.

Testing a plan's effectiveness should occur regularly; in instances where several business or organisations occupy the same space, joint emergency plans, formally agreed to by all parties, should be put into place.

Drills and exercises in preparation for foreseeable hazards are often held, with the participation of the services that will be involved in handling the emergency, and people who will be affected. Drills are held to prepare for the hazards of fires, tornadoes, lockdown for protection, earthquakes, etc.

Phases and personal activities[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2014) |

Emergency management consists of five phases: prevention, mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery.[27]

Prevention[]

Preventive measures are taken at the domestic and international levels and are designed to provide permanent protection from disasters. The risk of loss of life and injury can be mitigated with good evacuation plans, environmental planning, and design standards. In January 2005, 168 Governments adopted a 10-year plan to make the world safer from natural hazards at the World Conference on Disaster Reduction, held in Kobe, Hyogo, Japan, the results of which were adapted in a framework called the Hyogo Framework for Action. [28]

Mitigation strategy[]

Disaster mitigation measures are those that eliminate or reduce the impacts and risks of hazards through proactive measures taken before an emergency or disaster occurs.

Preventive or mitigation measures vary for different types of disasters. In earthquake prone areas, these preventive measures might include structural changes such as the installation of an earthquake valve to instantly shut off the natural gas supply, seismic retrofits of property, and the securing of items inside a building. The latter may include the mounting of furniture, refrigerators, water heaters and breakables to the walls, and the addition of cabinet latches. In flood prone areas, houses can be built on poles/stilts. In areas prone to prolonged electricity black-outs installation of a generator ensures continuation of electrical service. The construction of storm cellars and fallout shelters are further examples of personal mitigative actions.

Preparedness[]

Preparedness focuses on preparing equipment and procedures for use when a disaster occurs. The equipment and procedures can be used to reduce vulnerability to disaster, to mitigate the impacts of a disaster, or to respond more efficiently in an emergency. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) proposed out a basic four-stage vision of preparedness flowing from mitigation to preparedness to response to recovery and back to mitigation in a circular planning process.[29] This circular, overlapping model has been modified by other agencies, taught in emergency classes, and discussed in academic papers.[30]

FEMA also operates a Building Science Branch that develops and produces multi-hazard mitigation guidance that focuses on creating disaster-resilient communities to reduce loss of life and property.[31] FEMA advises citizens to prepare their homes with some emergency essentials in the event food distribution lines are interrupted. FEMA has subsequently prepared for this contingency by purchasing hundreds of thousands of freeze dried food emergency meals ready to eat (MREs) to dispense to the communities where emergency shelter and evacuations are implemented.

Some guidelines for household preparedness were published online by the State of Colorado on the topics of water, food, tools, and so on.[32]

Emergency preparedness can be difficult to measure.[33] CDC focuses on evaluating the effectiveness of its public health efforts through a variety of measurement and assessment programs.[34]

Local Emergency Planning Committees[]

Local Emergency Planning Committees (LEPCs) are required by the United States Environmental Protection Agency under the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act to develop an emergency response plan, review the plan at least annually, and provide information about chemicals in the community to local citizens.[35] This emergency preparedness effort focuses on hazards presented by use and storage of extremely hazardous and toxic chemicals.[36] Particular requirements of LEPCs include

- Identification of facilities and transportation routes of extremely hazardous substances

- Description of emergency response procedures, on and off site

- Designation of a community coordinator and facility emergency coordinator(s) to implement the plan

- Outline of emergency notification procedures

- Description of how to determine the probable affected area and population by releases

- Description of local emergency equipment and facilities and the persons responsible for them

- Outline of evacuation plans

- A training program for emergency responders (including schedules)

- Methods and schedules for exercising emergency response plans

According to the EPA, "Many LEPCs have expanded their activities beyond the requirements of EPCRA, encouraging accident prevention and risk reduction, and addressing homeland security in their communities", and the Agency offers advice on how to evaluate the effectiveness of these committees.[37]

Preparedness measures[]

The image captions in this section require cleanup to comply with Wikipedia guidelines for trivial wording. (June 2017) |

Preparedness measures can take many forms ranging from focusing on individual people, locations or incidents to broader, government-based "all hazard" planning.[38] There are a number of preparedness stages between "all hazard" and individual planning, generally involving some combination of both mitigation and response planning. Business continuity planning encourages businesses to have a Disaster Recovery Plan. Community- and faith-based organizations mitigation efforts promote field response teams and inter-agency planning.[39]

School-based response teams cover everything from live shooters to gas leaks and nearby bank robberies.[40] Educational institutions plan for cyberattacks and windstorms.[41] Industry specific guidance exists for horse farms,[42] boat owners[43] and more. A 2013 survey found that only 19% of American families felt that they were "very prepared" for a disaster.[44]

Disasters take a variety of forms to include earthquakes, tsunamis, or regular structure fires. That a disaster or emergency is not large scale in terms of population or acreage impacted or duration does not make it any less of a disaster for the people or area impacted and much can be learned about preparedness from so-called small disasters.[45] The Red Cross stated that it responds to nearly 70,000 disasters a year, the most common of which is a single family fire.[46]

The basic theme behind preparedness is to be ready for an emergency and there are a number of different variations of being ready based on an assessment of what sort of threats exist. Nonetheless, there is basic guidance for preparedness that is common despite an area's specific dangers. FEMA recommends that everyone have a three-day survival kit for their household.[47] Because individual household sizes and specific needs might vary, FEMA's recommendations are not item specific, but the list includes:

- Three-day supply of nonperishable food.

- Three-day supply of water – one gallon of water per person, per day.

- Portable, battery-powered radio or television and extra batteries.

- Flashlight and extra batteries.

- First aid kit and manual.

- Sanitation and hygiene items (e.g. toilet paper, menstrual hygiene products).

- Matches and waterproof container.

- Whistle.

- Extra clothing.

- Kitchen accessories and cooking utensils, including a can opener.

- Photocopies of credit and identification cards.

- Cash and coins.

- Special needs items, such as prescription medications, eyeglasses, contact lens solutions, and hearing aid batteries.

- Items for infants, such as formula, diapers, bottles, and pacifiers.

Along similar lines, the CDC has its own list for a proper disaster supply kit.[48]

- Water—one gallon per person, per day

- Food—nonperishable, easy-to-prepare items

- Flashlight

- Battery powered or hand crank radio (NOAA Weather Radio, if possible)

- Extra batteries

- First aid kit

- Medications (7-day supply), other medical supplies, and medical paperwork (e.g., medication list and pertinent medical information)

- Multipurpose tool (e.g., Swiss army knife)

- Sanitation and personal hygiene items

- Copies of personal documents (e.g., proof of address, deed/lease to home, passports, birth certificates, and insurance policies)

- Cell phone with chargers

- Family and emergency contact information

- Extra cash

- Emergency blanket

- Map(s) of the area

- Extra set of car keys and house keys

- Manual can opener

FEMA suggests having a Family Emergency Plan for such occasions.[49] Because family members may not be together when disaster strikes, this plan should include reliable contact information for friends or relatives who live outside of what would be the disaster area for household members to notify they are safe or otherwise communicate with each other. Along with contact information, FEMA suggests having well-understood local gathering points if a house must be evacuated quickly to avoid the dangers of re-reentering a burning home.[50] Family and emergency contact information should be printed on cards and put in each family member's backpack or wallet. If family members spend a significant amount of time in a specific location, such as at work or school, FEMA suggests learning the emergency preparation plans for those places.[49] FEMA has a specific form, in English and in Spanish, to help people put together these emergency plans, though it lacks lines for email contact information.[49]

Like children, people with disabilities and other special needs have special emergency preparation needs. While "disability" has a specific meaning for specific organizations such as collecting Social Security benefits,[51] for the purposes of emergency preparedness, the Red Cross uses the term in a broader sense to include people with physical, medical, sensor or cognitive disabilities or the elderly and other special needs populations.[52] Depending on the disability, specific emergency preparations may be required. FEMA's suggestions for people with disabilities include having copies of prescriptions, charging devices for medical devices such as motorized wheelchairs and a week's supply of medication readily available or in a "go stay kit."[53] In some instances, a lack of competency in English may lead to special preparation requirements and communication efforts for both individuals and responders.[54]

FEMA notes that long term power outages can cause damage beyond the original disaster that can be mitigated with emergency generators or other power sources to provide an emergency power system.[55] The United States Department of Energy states that 'homeowners, business owners, and local leaders may have to take an active role in dealing with energy disruptions on their own."[56] This active role may include installing or other procuring generators that are either portable or permanently mounted and run on fuels such as propane or natural gas[57] or gasoline.[58] Concerns about carbon monoxide poisoning, electrocution, flooding, fuel storage and fire lead even small property owners to consider professional installation and maintenance.[55] Major institutions like hospitals, military bases and educational institutions often have or are considering extensive backup power systems.[59] Instead of, or in addition to, fuel-based power systems, solar, wind and other alternative power sources may be used.[60] Standalone batteries, large or small, are also used to provide backup charging for electrical systems and devices ranging from emergency lights to computers to cell phones.[61]

The United States Department of Health and Human Services addresses specific emergency preparedness issues hospitals may have to respond to, including maintaining a safe temperature, providing adequate electricity for life support systems and even carrying out evacuations under extreme circumstances.[62] FEMA encourages all businesses to have businesses to have an emergency response plan[63] and the Small Business Administration specifically advises small business owners to also focus emergency preparedness and provides a variety of different worksheets and resources.[64]

FEMA cautions that emergencies happen while people are travelling as well[65] and provides guidance around emergency preparedness for a range travelers to include commuters,[66] Commuter Emergency Plan and holiday travelers.[67]Ready.gov has a number of emergency preparations specifically designed for people with cars.[68] These preparations include having a full gas tank, maintaining adequate windshield wiper fluid and other basic car maintenance tips. Items specific to an emergency include:

- Jumper cables: might want to include flares or reflective triangle

- Flashlights, to include extra batteries (batteries have less power in colder weather)

- First aid kit, to include any necessary medications, baby formula and diapers if caring for small children

- Non-perishable food such as canned food (be alert to liquids freezing in colder weather), and protein rich foods like nuts and energy bars

- Manual can opener

- At least 1 gallon of water per person a day for at least 3 days (be alert to hazards of frozen water and resultant container rupture)

- Basic toolkit: pliers, wrench, screwdriver

- Pet supplies: food and water

- Radio: battery or hand cranked

- For snowy areas: cat litter or sand for better tire traction; shovel; ice scraper; warm clothes, gloves, hat, sturdy boots, jacket and an extra change of clothes

- Blankets or sleeping bags

- Charged Cell Phone: and car charger

In addition to emergency supplies and training for various situations, FEMA offers advice on how to mitigate disasters. The Agency gives instructions on how to retrofit a home to minimize hazards from a flood, to include installing a backflow prevention device, anchoring fuel tanks and relocating electrical panels.[69]

Given the explosive danger posed by natural gas leaks, Ready.gov states unequivocally that "It is vital that all household members know how to shut off natural gas" and that property owners must ensure they have any special tools needed for their particular gas hookups. Ready.gov also notes that "It is wise to teach all responsible household members where and how to shut off the electricity," cautioning that individual circuits should be shut off before the main circuit. Ready.gov further states that "It is vital that all household members learn how to shut off the water at the main house valve" and cautions that the possibility that rusty valves might require replacement.[70]

Response[]

The response phase of an emergency may commence with Search and Rescue but in all cases the focus will quickly turn to fulfilling the basic humanitarian needs of the affected population. This assistance may be provided by national or international agencies and organizations. Effective coordination of disaster assistance is often crucial, particularly when many organizations respond and local emergency management agency (LEMA) capacity has been exceeded by the demand or diminished by the disaster itself. The National Response Framework is a United States government publication that explains responsibilities and expectations of government officials at the local, state, federal, and tribal levels. It provides guidance on Emergency Support Functions that may be integrated in whole or parts to aid in the response and recovery process.

On a personal level the response can take the shape either of a shelter-in-place or an evacuation.

In a shelter-in-place scenario, a family would be prepared to fend for themselves in their home for many days without any form of outside support. In an evacuation, a family leaves the area by automobile or other mode of transportation, taking with them the maximum amount of supplies they can carry, possibly including a tent for shelter. If mechanical transportation is not available, evacuation on foot would ideally include carrying at least three days of supplies and rain-tight bedding, a tarpaulin and a bedroll of blankets.

Organized response includes evacuation measures, search and rescue missions, provision of other emergency services, provision of basic needs, and recovery or ad hoc substitution of critical infrastructure. A range of technologies are used for these purposes.

Donations are often sought during this period, especially for large disasters that overwhelm local capacity. Due to efficiencies of scale, money is often the most cost-effective donation if fraud is avoided. Money is also the most flexible, and if goods are sourced locally then transportation is minimized and the local economy is boosted. Some donors prefer to send gifts in kind, however these items can end up creating issues, rather than helping. One innovation by Occupy Sandy volunteers is to use a donation registry, where families and businesses impacted by the disaster can make specific requests, which remote donors can purchase directly via a web site.

Medical considerations will vary greatly based on the type of disaster and secondary effects. Survivors may sustain a multitude of injuries to include lacerations, burns, near drowning, or crush syndrome.

Amanda Ripley points out that among the general public in fires and large-scale disasters, there is a remarkable lack of panic and sometimes dangerous denial of, lack of reaction to, or rationalization of warning signs that should be obvious. She says that this is often attributed to local or national character, but appears to be universal, and is typically followed by consultations with nearby people when the signals finally get enough attention. Disaster survivors advocate training everyone to recognize warning signs and practice responding.[71]

Recovery[]

The recovery phase starts after the immediate threat to human life has subsided. The immediate goal of the recovery phase is to bring the affected area back to normalcy as quickly as possible. During reconstruction, it is recommended to consider the location or construction material of the property.

The most extreme home confinement scenarios include war, famine, and severe epidemics and may last a year or more. Then recovery will take place inside the home. Planners for these events usually buy bulk foods and appropriate storage and preparation equipment, and eat the food as part of normal life. A simple balanced diet can be constructed from vitamin pills, whole-grain wheat, beans, dried milk, corn, and cooking oil.[72] Vegetables, fruits, spices and meats, both prepared and fresh-gardened, are included when possible.

Psychological First Aid

In the immediate aftermath of a disaster, psychological first aid is provided by trained lay people to assist disaster affected populations with coping and recovery.[73] Trained workers offer practical support, assistance with securing basic needs such as food and water, and referrals to needed information and services. Psychological first aid is similar to medical first aid in that providers do not need to be licensed clinicians. It is not psychotherapy, counseling, or debriefing. The goal of psychological first aid is to help people with their long-term recovery by offering social, physical, and emotional support, contributing to a hopeful, calm, and safe environment, and enabling them to help themselves and their communities.[74]

Research states that mental health is often neglected by first responders. Disaster can have lasting psychological impacts on those affected. When individuals are supported in processing their emotional experiences to the disaster this leads to increases in resilience, increases in the capacity to help others through crises, and increases in community engagement. When processing of emotional experiences is done in a collective manner, this leads to greater solidarity following disaster. As such, emotional experiences have an inherent adaptiveness within them, however the opportunity for these to be reflected on and processed is necessary for this growth to occur. [75]

Psychological preparedness is a type of emergency preparedness and specific mental health preparedness resources are offered for mental health professionals by organizations such as the Red Cross.[46] These mental health preparedness resources are designed to support both community members affected by a disaster and the disaster workers serving them. CDC has a website devoted to coping with a disaster or traumatic event.[76] After such an event, the CDC, through the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), suggests that people seek psychological help when they exhibit symptoms such as excessive worry, crying frequently, an increase in irritability, anger, and frequent arguing, wanting to be alone most of the time, feeling anxious or fearful, overwhelmed by sadness, confused, having trouble thinking clearly and concentrating, and difficulty making decisions, increased alcohol and/or substance use, increased physical (aches, pains) complaints such as headaches and trouble with "nerves."

As a profession[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2014) |

Professional emergency managers can focus on government and community preparedness, or private business preparedness. Training is provided by local, state, federal and private organizations and ranges from public information and media relations to high-level incident command and tactical skills.

In the past, the field of emergency management has been populated mostly by people with a military or first responder background. The field has diversified, with many managers coming from a variety of backgrounds. Educational opportunities are increasing for those seeking undergraduate and graduate degrees in emergency management or a related field. There are over 180 schools in the US with emergency management-related programs, but only one doctoral program specifically in emergency management.[77]

Professional certifications such as Certified Emergency Manager (CEM)[78] and Certified Business Continuity Professional (CBCP)[79][80] are becoming more common as professional standards are raised throughout the field, particularly in the United States. There are also professional organizations for emergency managers, such as the National Emergency Management Association and the International Association of Emergency Managers.

Principles[]

In 2007, Dr. Wayne Blanchard of FEMA's Emergency Management Higher Education Project, at the direction of Dr. Cortez Lawrence, Superintendent of FEMA's Emergency Management Institute, convened a working group of emergency management practitioners and academics to consider principles of emergency management. This was the first time the principles of the discipline were to be codified. The group agreed on eight principles to guide the development of a doctrine of emergency management:[81]

- Comprehensive – consider and take into account all hazards, all phases, all stakeholders and all impacts relevant to disasters.

- Progressive – anticipate future disasters and take preventive and preparatory measures to build disaster-resistant and disaster-resilient communities.

- Risk-driven – use sound risk management principles (hazard identification, risk analysis, and impact analysis) in assigning priorities and resources.

- Integrated – ensure unity of effort among all levels of government and all elements of a community.

- Collaborative – create and sustain broad and sincere relationships among individuals and organizations to encourage trust, advocate a team atmosphere, build consensus, and facilitate communication.

- Coordinated – synchronize the activities of all relevant stakeholders to achieve a common purpose.

- Flexible – use creative and innovative approaches in solving disaster challenges.

- Professional – value a science and knowledge-based approach; based on education, training, experience, ethical practice, public stewardship and continuous improvement.

Tools[]

Emergency management information systems[]

The continuity feature of emergency management resulted in a new concept: emergency management information systems (EMIS). For continuity and interoperability between emergency management stakeholders, EMIS supports an infrastructure that integrates emergency plans at all levels of government and non-government involvement for all four phases of emergencies. In the healthcare field, hospitals utilize the Hospital Incident Command System (HICS), which provides structure and organization in a clearly defined chain of command.[citation needed]

Populations Explorer[]

In 2008, the U.S. Agency for International Development created a web-based tool for estimating populations impacted by disasters called Population Explorer.[82] The tool uses land scan population data, developed by Oak Ridge National Laboratory, to distribute population at a resolution 1 km2 for all countries in the world. Used by USAID's FEWS NET Project to estimate populations vulnerable to, or impacted by, food insecurity. Population Explorer is gaining wide use in a range of emergency analysis and response actions, including estimating populations impacted by floods in Central America and the Pacific Ocean tsunami event in 2009.

SMAUG model – a basis for prioritizing hazard risks[]

In emergency or disaster management the SMAUG model of identifying and prioritizing risk of hazards associated with natural and technological threats is an effective tool. SMAUG stands for Seriousness, Manageability, Acceptability, Urgency and Growth and are the criteria used for prioritization of hazard risks. The SMAUG model provides an effective means of prioritizing hazard risks based upon the aforementioned criteria in order to address the risks posed by the hazards to the avail of effecting effective mitigation, reduction, response and recovery methods.[83]

- Seriousness

- "The relative impact in terms of people and dollars," which includes the potential for lives to be lost and potential for injury as well as the physical, social, and economic losses that may be incurred.

- Manageability

- The "relative ability to mitigate or reduce the hazard (through managing the hazard, or the community or both)". Hazards presenting a high risk and as such requiring significant amounts of risk reduction initiatives will be rated high.[83]

- Acceptability

- The degree to which the risk of hazard is acceptable in terms of political, environmental, social and economic impact

- Urgency

- This is related to the probability of risk of hazard and is defined in terms of how imperative it is to address the hazard[83]

- Growth

- The potential for the hazard or event to expand or increase in either probability or risk to community or both. Should vulnerability increase, potential for growth may also increase.

An example of the numerical ratings for each of the four criteria is shown below:[84]

| Manageability | High = 7+ | Medium = 5–7 | Low = 0–4 |

| Urgency | High = <20yr | Medium = >20yr | Low = 100yrs |

| Acceptability | High priority – poses more significant risk | low priority – Lower risk of hazard impact | |

| Growth | High = 3 | Medium = 2 | Low = 1 |

| Seriousness | High = 4–5 | Medium = 2–3 | Low = 0–1 |

Memory institutions and cultural property[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2014) |

Professionals from memory institutions (e.g., museums, historical societies, etc.) are dedicated to preserving cultural heritage—objects and records. This has been an increasingly major component within the emergency management field as a result of the heightened awareness following the September 11 attacks in 2001, the hurricanes in 2005, and the collapse of the Cologne Archives.

International organizations[]

International Emergency Management Society[]

The International Emergency Management Society (TIEMS) is an international non-profit NGO, registered in Belgium. TIEMS is a global forum for education, training, certification, and policy in emergency and disaster management. TIEMS' goal is to develop and bring modern emergency management tools, and techniques into practice, through the exchange of information, methodology innovations and new technologies.

TIEMS provides a platform for stakeholders to meet, network, and learn about new technical and operational methodologies and focuses on cultural differences to be understood and included in the society's events, education, and research programs by establishing local chapters worldwide. Today, TIEMS has chapters in Benelux, Romania, Finland, Italy, Middle East and North Africa (MENA), Iraq, India, Korea, Japan and China.

International Association of Emergency Managers[]

The International Association of Emergency Managers (IAEM) is a non-profit educational organization aimed at promoting the goals of saving lives and property protection during emergencies. The mission of IAEM is to serve its members by providing information, networking and professional opportunities, and to advance the emergency management profession.

It has seven councils around the world: Asia,[85] Canada,[86] Europa,[87] International,[88] Oceania,[89] Student[90] and USA.[91]

The Air Force Emergency Management Association, affiliated by membership with the IAEM, provides emergency management information and networking for U.S. Air Force Emergency Management personnel.

International Recovery Platform[]

The International Recovery Platform (IRP) is a joint initiative of international organizations, national and local governments, and non-governmental organizations engaged in disaster recovery, and seeking to transform disasters into opportunities for sustainable development.[92]

IRP was established after the Second UN World Conference on Disaster Reduction (WCDR) in Kobe, Japan, in 2005 to support the implementation of the Hyogo Framework for Action (HFA) by addressing the gaps and constraints experienced in the context of post-disaster recovery. After a decade of functioning as an international source of knowledge on good recovery practice, IRP is now focused on a more specialized role, highlighted in the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 as an “international mechanism for sharing experience and lessons associated with build back better”[93][94]

The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement[]

The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) works closely with National Red Cross and Red Crescent societies in responding to emergencies, many times playing a pivotal role. In addition, the IFRC may deploy assessment teams, e.g. Field Assessment and Coordination Teams (FACT),[95] to the affected country if requested by the national society. After assessing the needs, Emergency Response Units (ERUs)[96] may be deployed to the affected country or region. They are specialized in the response component of the emergency management framework.

Baptist Global Response[]

Baptist Global Response (BGR) is a disaster relief and community development organization. BGR and its partners respond globally to people with critical needs worldwide, whether those needs arise from chronic conditions or acute crises such as natural disasters. While BGR is not an official entity of the Southern Baptist Convention, it is rooted in Southern Baptist life and is the international partnership of Southern Baptist Disaster Relief teams, which operate primarily in the US and Canada.[97]

United Nations[]

The United Nations system rests with the Resident Coordinator within the affected country. However, in practice, the UN response will be coordinated by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UN-OCHA), by deploying a UN Disaster Assessment and Coordination (UNDAC) team, in response to a request by the affected country's government. Finally UN-SPIDER designed as a networking hub to support disaster management by application of satellite technology[98]

World Bank[]

Since 1980, the World Bank has approved more than 500 projects related to disaster management, dealing with both disaster mitigation as well as reconstruction projects, amounting to more than US$40 billion. These projects have taken place all over the world, in countries such as Argentina, Bangladesh, Colombia, Haiti, India, Mexico, Turkey and Vietnam.[99]

Prevention and mitigation projects include forest fire prevention measures, such as early warning measures and education campaigns; early-warning systems for hurricanes; flood prevention mechanisms (e.g. shore protection, terracing, etc.); and earthquake-prone construction.[99] In a joint venture with Columbia University under the umbrella of the ProVention Consortium Project the World Bank has established a Global Risk Analysis of Natural Disaster Hotspots.[100]

In June 2006, the World Bank, in response to the HFA, established the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR), a partnership with other aid donors to reduce disaster losses. GFDRR helps developing countries fund development projects and programs that enhance local capacities for disaster prevention and emergency preparedness.[101]

European Union[]

In 2001 the EU adopted the Community Mechanism for Civil Protection to facilitate cooperation in the event of major emergencies requiring urgent response actions. This also applies to situations where there may be an imminent threat as well.[102]

The heart of the Mechanism is the Monitoring and Information Center (MIC), part of the European Commission's Directorate-General for Humanitarian Aid & Civil Protection. It gives countries 24-hour access to civil protections available amongst all the participating states. Any country inside or outside the Union affected by a major disaster can make an appeal for assistance through the MIC. It acts as a communication hub and provides useful and updated information on the actual status of an ongoing emergency.[103]

Other organization[]

National organizations[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2014) |

Australia[]

Natural disasters are part of life in Australia. Heatwaves have killed more Australians than any other type of natural disaster in the 20th century.[citation needed] Australia's emergency management processes embrace the concept of the prepared community. The principal government agency in achieving this is Emergency Management Australia.

Canada[]

Public Safety Canada is Canada's national emergency management agency. Each province is required to have both legislation for dealing with emergencies and provincial emergency management agencies which are typically called "Emergency Measures Organizations" (EMO). Public Safety Canada coordinates and supports the efforts of federal organizations as well as other levels of government, first responders, community groups, the private sector, and other nations. The Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Act (SC 2005, c.10) defines the powers, duties and functions of PS are outlined. Other acts are specific to individual fields such as corrections, law enforcement, and national security.

China[]

The State Council of the People's Republic of China is responsible for level I and II public emergency incidents except for level II natural disasters which are taken by the Ministry of Emergency Management. Level III and IV non-natural-disasters public emergency incidents are taken by provincial and prefectural government. Level I and IV natural disasters will be managed by National Committee for Disaster Reduction while for level II and III natural disasters it's the Ministry of Emergency Management.

Germany[]

In Germany the Federal Government controls the German Katastrophenschutz (disaster relief), the Technisches Hilfswerk (Federal Agency for Technical Relief, THW), and the Zivilschutz (civil protection) programs coordinated by the Federal Office of Civil Protection and Disaster Assistance. Local fire department units, the German Armed Forces (Bundeswehr), the German Federal Police and the 16 state police forces (Länderpolizei) are also deployed during disaster relief operations.

There are several private organizations in Germany that also deal with emergency relief. Among these are the German Red Cross, Johanniter-Unfall-Hilfe (the German equivalent of the St. John Ambulance), the Malteser-Hilfsdienst, and the Arbeiter-Samariter-Bund. As of 2006, there is a program of study at the University of Bonn leading to the degree "Master in Disaster Prevention and Risk Governance"[104] As a support function radio amateurs provide additional emergency communication networks with frequent trainings.

India[]

The National Disaster Management Authority is the primary government agency responsible for planning and capacity-building for disaster relief. Its emphasis is primarily on strategic risk management and mitigation, as well as developing policies and planning.[105] The National Institute of Disaster Management is a policy think-tank and training institution for developing guidelines and training programs for mitigating disasters and managing crisis response.

The National Disaster Response Force is the government agency primarily responsible for emergency management during natural and man-made disasters, with specialized skills in search, rescue and rehabilitation.[106] The Ministry of Science and Technology also contains an agency that brings the expertise of earth scientists and meteorologists to emergency management. The Indian Armed Forces also plays an important role in the rescue/recovery operations after disasters.

Aniruddha's Academy of Disaster Management (AADM) is a non-profit organization in Mumbai, India, with "disaster management" as its principal objective.

Japan[]

The Fire and Disaster Management Agency is the national emergency management agency attached to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications in Japan.

Malaysia[]

In Malaysia, National Disaster Management Agency (NADMA Malaysia) is the focal point in managing disaster. It was established under the Prime Minister's Department on 2 October 2015 following the flood in 2014 and took over from the National Security Council. The Ministry of Home Affairs, Ministry of Health and Ministry of Housing, Urban Wellbeing and Local Government are also responsible for managing emergencies. Several agencies involved in emergency management are Royal Malaysian Police, Malaysian Fire and Rescue Department, Malaysian Civil Defence Force, Ministry of Health Malaysia and Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency. There were also some voluntary organisations who involved themselves in emergency/disaster management such as St. John Ambulance of Malaysia and the Malaysian Red Crescent Society.

Nepal[]

The Nepal Risk Reduction Consortium (NRRC) is based on Hyogo's framework and Nepal's National Strategy for Disaster Risk Management. This arrangement unites humanitarian and development partners with the government of Nepal and had identified 5 flagship priorities for sustainable disaster risk management.[107]

The Netherlands[]

In the Netherlands, the Ministry of Justice and Security is responsible for emergency preparedness and emergency management on a national level and operates a national crisis centre (NCC). The country is divided into 25 safety regions (Dutch: veiligheidsregio's). In a safety region, there are four components: the regional fire department, the regional department for medical care (ambulances and psycho-sociological care etc.), the regional dispatch and a section for risk- and crisis management. The regional dispatch operates for police, fire department and the regional medical care. The dispatch has all these three services combined into one dispatch for the best multi-coordinated response to an incident or an emergency. And also facilitates in information management, emergency communication and care of citizens. These services are the main structure for a response to an emergency. It can happen that, for a specific emergency, the co-operation with another service is needed, for instance the Ministry of Defence, water board(s) or Rijkswaterstaat. The safety region can integrate these other services into their structure by adding them to specific conferences on operational or administrative level.

All regions operate according to the Coordinated Regional Incident Management system.

New Zealand[]

In New Zealand, responsibility may be handled at either the local or national level depending on the scope of the emergency/disaster. Within each region, local governments are organized into 16 (CMGs). If local arrangements are overwhelmed, pre-existing mutual-support arrangements are activated. Central government has the authority to coordinate the response through the National Crisis Management Centre (NCMC), operated by the Ministry of Civil Defence & Emergency Management (MCDEM). These structures are defined by regulation,[108] and explained in The Guide to the National Civil Defence Emergency Management Plan 2006, roughly equivalent to the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency's National Response Framework.

New Zealand uses unique terminology for emergency management. Emergency management is rarely used, many government publications retaining the use of the term civil defence.[109][110][111] For example, the Minister of Civil Defence is responsible for the MCDEM. Civil Defence Emergency Management is a term in its own right, defined by statute.[112] The term "disaster" rarely appears in official publications; "emergency" and "incident" are the preferred terms,[113] with the term event also being used. For example, publications refer to the Canterbury Snow Event 2002.[114]

"4Rs" is the emergency management cycle used in New Zealand, its four phases are known as:[115]

- Reduction = Mitigation

- Readiness = Preparedness

- Response

- Recovery

Pakistan[]

Disaster management in Pakistan revolves around flood disasters and focuses on rescue and relief.

The Federal Flood Commission was established in 1977 under the Ministry of Water and Power to manage the issues of flood management on country-wide basis.[116]

The and the 2010 National Disaster Management Act were enacted after the 2005 Kashmir earthquake and 2010 Pakistan floods respectively to deal with disaster management. The primary central authority mandated to deal with whole spectrum of disasters and their management in the country is the National Disaster Management Authority.[117]

In addition, each province along with FATA, Gilgit Baltistan and Pakistani administered Kashmir has its own provincial disaster management authority responsible for implementing policies and plans for Disaster Management in the Province.[118]

Each district has its own District Disaster Management Authority for planning, coordinating and implementing body for disaster management and take all measures for the purposes of disaster management in the districts in accordance with the guidelines laid down by the National Authority and the Provincial Authority.[119]

Philippines[]

In the Philippines, the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council is responsible for the protection and welfare of people during disasters or emergencies. It is a working group composed of various government, non-government, civil sector and private sector organizations of the Government of the Republic of the Philippines. Headed by the Secretary of National Defense (under the Office of Civil Defense, the NDRRMCs implementing organization), it coordinates all the executive branches of government, presidents of the leagues of local government units throughout the country, the Armed Forces of the Philippines, Philippine National Police, Bureau of Fire Protection (which is an agency under the Department of the Interior and Local Government, and the public and private medical services in responding to natural and manmade disasters, as well as planning, coordination, and training of these responsible units. Non-governmental organizations such as the Philippine Red Cross also provide manpower and material support for NDRRMC.

Russia[]

In Russia, the Ministry of Emergency Situations (EMERCOM) is engaged in fire fighting, civil defense, and search and rescue after both natural and man-made disasters.

Somalia[]

In Somalia, the Federal Government announced in May 2013 that the Cabinet approved draft legislation on a new Somali Disaster Management Agency (SDMA), which had originally been proposed by the Ministry of Interior. According to the Prime Minister's Media Office, the SDMA leads and coordinate the government's response to various natural disasters, and is part of a broader effort by the federal authorities to re-establish national institutions. The Federal Parliament is now expected to deliberate on the proposed bill for endorsement after any amendments.[120]

Turkey[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (July 2021) |

Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency is responsible.

United Kingdom[]

Following the 2000 fuel protests and severe flooding that same year, as well as the foot-and-mouth crisis in 2001, the United Kingdom passed the Civil Contingencies Act 2004 (CCA). The CCA defined some organisations as Category 1 and 2 Responders and set responsibilities regarding emergency preparedness and response. It is managed by the Civil Contingencies Secretariat through Regional Resilience Forums and local authorities.

Disaster management training is generally conducted at the local level, and consolidated through professional courses that can be taken at the Emergency Planning College. Diplomas, undergraduate and postgraduate qualifications can be gained at universities throughout the country. The Institute of Emergency Management is a charity, established in 1996, providing consulting services for the government, media and commercial sectors. There are a number of professional societies for Emergency Planners including the Emergency Planning Society[121] and the Institute of Civil Protection and Emergency Management.[122]

One of the largest emergency exercises in the UK was carried out on 20 May 2007 near Belfast, Northern Ireland: a simulated plane crash-landing at Belfast International Airport. Staff from five hospitals and three airports participated in the drill, and almost 150 international observers assessed its effectiveness.[123]

United States[]

Disaster management in the United States has utilized the functional All-Hazards approach for over 20 years, in which managers develop processes (such as communication & warning or sheltering) rather than developing single-hazard or threat focused plans (e.g., a tornado plan). Processes are then mapped to specific hazards or threats, with the manager looking for gaps, overlaps, and conflicts between processes.

Given these notions, emergency managers must identify, contemplate, and assess possible man-made threats and natural threats that may affect their respective locales.[124] Because of geographical differences throughout the nation, a variety of different threats affect communities among the states. Thus, although similarities may exist, no two emergency plans will be completely identical. Additionally, each locale has different resources and capacities (e.g., budgets, personnel, equipment, etc.) for dealing with emergencies.[125] Each individual community must craft its own unique emergency plan that addresses potential threats that are specific to the locality.[126]

This creates a plan more resilient to unique events because all common processes are defined, and it encourages planning done by the stakeholders who are closer to the individual processes, such as a traffic management plan written by a public works director. This type of planning can lead to conflict with non-emergency management regulatory bodies, which require the development of hazard/threat specific plans, such as the development of specific H1N1 flu plans and terrorism-specific plans.

In the United States, all disasters are initially local, with local authorities, with usually a police, fire, or EMS agency, taking charge. Many local municipalities may also have a separate dedicated office of emergency management (OEM), along with personnel and equipment. If the event becomes overwhelming to the local government, state emergency management (the primary government structure of the United States) becomes the controlling emergency management agency. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), part of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), is the lead federal agency for emergency management. The United States and its territories are broken down into ten regions for FEMA's emergency management purposes. FEMA supports, but does not override, state authority.

The Citizen Corps is an organization of volunteer service programs, administered locally and coordinated nationally by DHS, which seek to mitigate disasters and prepare the population for emergency response through public education, training, and outreach. Most disaster response is carried out by volunteer organizations. In the US, the Red Cross is chartered by Congress to coordinate disaster response services. It is typically the lead agency handling shelter and feeding of evacuees. Religious organizations, with their ability to provide volunteers quickly, are usually integral during the response process. The largest being the Salvation Army,[127] with a primary focus on chaplaincy and rebuilding, and Southern Baptists who focus on food preparation and distribution,[128] as well as cleaning up after floods and fires, chaplaincy, mobile shower units, chainsaw crews and more. With over 65,000 trained volunteers, Southern Baptist Disaster Relief is one of the largest disaster relief organizations in the US.[129] Similar services are also provided by Methodist Relief Services, the Lutherans, and Samaritan's Purse. Unaffiliated volunteers show up at most large disasters. To prevent abuse by criminals, and for the safety of the volunteers, procedures have been implemented within most response agencies to manage and effectively use these 'SUVs' (Spontaneous Unaffiliated Volunteers).[130]

The US Congress established the Center for Excellence in Disaster Management and Humanitarian Assistance (COE) as the principal agency to promote disaster preparedness in the Asia-Pacific region.

The National Tribal Emergency Management Council (NEMC) is a non-profit educational organization developed for tribal organizations to share information and best practices, as well as to discuss issues regarding public health and safety, emergency management and homeland security, affecting those under First Nations sovereignty. NTMC is organized into regions, based on the FEMA 10-region system. NTMC was founded by the Northwest Tribal Emergency Management Council (NWTEMC), a consortium of 29 tribal nations and villages in Washington, Idaho, Oregon, and Alaska.

If a disaster or emergency is declared to be terror related or an "Incident of National Significance," the Secretary of Homeland Security will initiate the National Response Framework (NRF). The NRF allows the integration of federal resources with local, county, state, or tribal entities, with management of those resources to be handled at the lowest possible level, utilizing the National Incident Management System (NIMS).

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offer information for specific types of emergencies, such as disease outbreaks, natural disasters and severe weather, chemical and radiation accidents, etc. The Emergency Preparedness and Response Program of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health develops resources to address responder safety and health during responder and recovery operations.

FEMA's Emergency Management Institute[]

The Emergency Management Institute (EMI) serves as the national focal point for the development and delivery of emergency management training to enhance the capabilities of state, territorial, local, and tribal government officials; volunteer organizations; FEMA's disaster workforce; other Federal agencies; and the public and private sectors to minimize the impact of disasters and emergencies on the American public. EMI curricula are structured to meet the needs of this diverse audience with an emphasis on separate organizations working together in all-hazards emergencies to save lives and protect property. Particular emphasis is placed on governing doctrine such as the National Response Framework (NRF), National Incident Management System (NIMS), and the National Preparedness Guidelines.[131] EMI is fully accredited by the International Association for Continuing Education and Training (IACET) and the American Council on Education (ACE).[132]

Approximately 5,500 participants attend resident courses each year while 100,000 individuals participate in non-resident programs sponsored by EMI and conducted locally by state emergency management agencies under cooperative agreements with FEMA. Another 150,000 individuals participate in EMI-supported exercises, and approximately 1,000 individuals participate in the Chemical Stockpile Emergency Preparedness Program (CSEPP).[133]

The independent study program at EMI consists of free courses offered to United States citizens in Comprehensive Emergency Management techniques.[134] Course IS-1 is entitled "Emergency Manager: An Orientation to the Position" and provides background information on FEMA and the role of emergency managers in agency and volunteer organization coordination. The EMI Independent Study (IS) Program, a Web-based distance learning program open to the public, delivers extensive online training with approximately 200 courses. It has trained more than 2.8 million individuals. The EMI IS Web site receives 2.5 to 3 million visitors a day.[135]

See also[]

- Civil defense

- Computer emergency response team

- Business continuity planning

- Disaster medicine

- Disaster response

- Disaster risk reduction

- Emergency communication system

- Emergency sanitation

- Fire fighting

- Human capital flight

- Mass fatality incident

- Public health emergency (United States)

- Rohn emergency scale

- Search and rescue

NGOs:

- Catholic Relief Services[136]

- Consortium of British Humanitarian Agencies

- Disaster Accountability Project (DAP)

- GlobalMedic

- International Disaster Emergency Service (IDES)

- Médecins Sans Frontières

- NetHope

References[]

- ^ Zhou, Q., Huang, W., & Zhang, Y. (2011). Identifying critical success factors in emergency management using a fuzzy DEMATEL method. Safety science, 49(2), 243–252.

- ^ Hämäläinen R. P., Lindstedt M. R., Sinkko K. (2000). "Multiattribute risk analysis in nuclear emergency management". Risk Analysis. 20 (4): 455–468. doi:10.1111/0272-4332.204044. PMID 11051070.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ "Fact Sheet on Natural Disaster Recovery: Cleanup Hazard". www.osha.gov. Retrieved November 27, 2017.

- ^ "OSHA Fact Sheet_Keeping Workers Safe During Disaster Cleanup and Recovery" (PDF). November 27, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Bandino, Justin P.; Hang, Anna; Norton, Scott A. (2015). "The Infectious and Noninfectious Dermatological Consequences of Flooding: A Field Manual for the Responding Provider". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 16 (5): 399–424. doi:10.1007/s40257-015-0138-4. PMID 26159354. S2CID 35243897.

- ^ "CDC – Hazard Based Guidelines: Protective Equipment for Workers in Hurricane Flood Response – NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic". www.cdc.gov. September 13, 2017. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- ^ "Earthquake Preparedness and Response | Preparedness | Occupational Safety and Health Administration". www.osha.gov. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Young, Stacy; Balluz, Lina; Malilay, Josephine (April 25, 2004). "Natural and technologic hazardous material releases during and after natural disasters: a review". Science of the Total Environment. 322 (1): 3–20. Bibcode:2004ScTEn.322....3Y. doi:10.1016/S0048-9697(03)00446-7. PMID 15081734.

- ^ "OSHA Annotated PELs | Occupational Safety and Health Administration". www.osha.gov. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- ^ "CDC – NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards (NPG) Introduction". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- ^ "Mold – Natural Disasters and Severe Weather". www.cdc.gov. December 8, 2017.

- ^ EPA,OAR,ORIA,IED, US (October 22, 2014). "Ten Things You Should Know about Mold – US EPA". US EPA.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2016-10/documents/moldguide12.pdf

- ^ "Mold Removal After a Disaster-PSAs for Disasters". www.cdc.gov. February 28, 2019.

- ^ "Handling Human Remains After a Disaster|Natural Disasters and Severe Weather". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- ^ "WHO | Flooding and communicable diseases fact sheet". www.who.int. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- ^ "American Psychological Association_Disasters". Archived from the original on December 29, 2009. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- ^ "Vibrio vulnificus|Natural Disasters and Severe Weather". www.cdc.gov. October 11, 2017. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- ^ "Emergency Responders: Tips for taking care of yourself". emergency.cdc.gov. November 7, 2017. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- ^ ann.lynsen (June 20, 2014). "Disaster Preparedness, Response, and Recovery". www.samhsa.gov. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- ^ "Defining Volunteer Roles in Preparation for Disaster Response".

- ^ "OSHA's Hazard Exposure and Risk Assessment Matrix for Hurricane Response and Recovery Work: Employer Responsibilities and Worker Rights". www.osha.gov. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- ^ "Emergency action plans. – 1910.38 | Occupational Safety and Health Administration". www.osha.gov. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- ^ "Emergency action plans. - 1910.38 | Occupational Safety and Health Administration". December 1, 2017. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ "08/07/1981 – Fire detection and employee alarm systems. | Occupational Safety and Health Administration". www.osha.gov. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- ^ "Reporting fatalities, hospitalizations, amputations, and losses of an eye as a result of work-related incidents to OSHA. – 1904.39 | Occupational Safety and Health Administration". www.osha.gov. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- ^ Mission Areas | FEMA.gov

- ^ "What is the Hyogo Framework for Action?". UN office for disaster risk reduction. eird.org. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ "Animals in Disasters". Training.fema.gov. Archived from the original on July 14, 2015. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ^ Baird, Malcolm E. (2010). "The "Phases" of Emergency Management" (PDF). Vanderbilt Center for Transportation Research. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Building Science". fema.gov. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Personal Plan". READY Colorado. State of Colorado. Archived from the original on March 25, 2015. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ "Rand Homeland Security" (PDF). Rand.org. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Public Health Emergency Preparedness Cooperative Agreement" (PDF). Cdc.gov. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "US Environmental Protection Agency | US EPA". .epa.gov. January 28, 2015. Archived from the original on March 9, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "The Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act" (PDF). Epa.gov. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Masuring Progress in Chemical Safety : A Guide for Local Emergency Planning Committees and Similar Groups" (PDF). Epa.gov. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Guide for All-Hazard Emergency Operations Planning September 1996" (PDF). fema.gov.

- ^ "Community-Based Pre-Disaster Mitigation" (PDF). Fema.gov. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "School-Based Emergency preparedness : A National analysis and recommended Protocol" (PDF). Archive.ahrq.gov. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ AHRQ Publication No. 09-0013 January 2009 UMass System Office Hazard Mitigation Plan Draft (December 2013)

- ^ "Horse Farm Disaster Preparedness". TheHorse.com. November 26, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ [1] Archived November 21, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Your family's emergency kit is probably a disaster". Cnn.com. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ [2] Archived December 17, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Disaster Mental Health : Introduction". a1881.g.akamai.net. Archived from the original on March 10, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Basic Preparedness" (PDF). Fema.gov. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "CDC Emergency preparedness and You | Gather Emergency Supplies | Disaster Supplies Kit". Emergency.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on March 17, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Make A Plan". Ready.gov. January 29, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Escape From Fire!" (PDF). Usfa.fema.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 10, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Who Will Qualify For Disability? – What Qualifying Is Based On". Ssdrc.com. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Preparing for Disaster for People with Disabilities and other Special Needs" (PDF). Redcross.org. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ [3] (archived link, February 11, 2015)

- ^ "Ready New York : Preparing for Emergencies in new York City" (PDF). Nyc.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Install a Generator for Emergency Power" (PDF). Fema.gov. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Community Guidelines for Energy Emergencies | Department of Energy". Energy.gov. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ Generac Power Systems, Inc. "Generac Home Backup Power – Home & Portable Generator – Generac Power Systems". generac.com. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Duromax RV Grade 4,400-Watt 7.0 HP Gasoline Powered Portable Generator with Wheel Kit-XP4400 – The Home Depot". The Home Depot. October 15, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Microgrid Effects and Opportunities for Utilities" (PDF). Burnsmcd.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 9, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Alternative Energy Sources For Homes During Emergencies". House Hold Power Generator. August 18, 2013. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Goal Zero Yeti 400". Crutchfield. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Hospital Evacuation Decision Guide: Chapter 2. Pre-Disaster Self-Assessment". Archive.ahrq.gov. June 30, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Emergency Response Plan". Ready.gov. December 19, 2012. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Prepare for emergencies". U.S. Small Business Administration. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ "FEMA.gov Communities – National Preparedness Community Main Group – Travel Preparedness Tips: How to Be Ready When On The Go". Community.fema.gov. July 31, 2014. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Commuter Emergency Plan" (PDF). Fema.gov. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

- ^ "Planes, Trains, and Automobiles – Holiday Travel Safety Tips". FEMA.gov. June 18, 2012. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Car Safety". Ready.gov. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Homeowner's Guide to Retrofitting" (PDF). Fema.gov. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "Utility Shut-off & Safety". Ready.gov. Archived from the original on March 15, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ Amanda Ripley (January 29, 2018). "PrepTalks: Amanda Ripley "The Unthinkable: Lessons from Survivors"".

- ^ "Federal Emergency Management Agency". FEMA.gov. Retrieved August 11, 2013.

- ^ Hennebert, Marc-Antonin (2009). "Cross-Border Social Dialogue and Agreements: An Emerging Global Industrial Relations Framework?, Sous la direction de Konstantinos Papadakis, Genève : Institut international d'études sociales, Organisation internationale du travail, 2008, 288 p., ISBN 978-92-9014-862-3 (print) et ISBN 978-92-9014-863-0 (web pdf)". Relations Industrielles. 64 (3): 530. doi:10.7202/038555ar. ISSN 0034-379X.

- ^ Hennebert, Marc-Antonin (2009). "Cross-Border Social Dialogue and Agreements: An Emerging Global Industrial Relations Framework?, Sous la direction de Konstantinos Papadakis, Genève : Institut international d'études sociales, Organisation internationale du travail, 2008, 288 p., ISBN 978-92-9014-862-3 (print) et ISBN 978-92-9014-863-0 (web pdf)". Relations Industrielles. 64 (3): 530. doi:10.7202/038555ar. ISSN 0034-379X.