Tomb of Tutankhamun

| KV62 | |

|---|---|

| Burial site of Tutankhamun | |

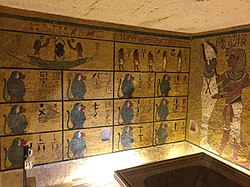

The wall decorations in KV62's burial chamber are modest in comparison with other royal tombs found in the Valley of the Kings. | |

KV62 | |

| Coordinates | 25°44′25.4″N 32°36′05.1″E / 25.740389°N 32.601417°ECoordinates: 25°44′25.4″N 32°36′05.1″E / 25.740389°N 32.601417°E |

| Location | East Valley of the Kings |

| Discovered | 4 November 1922 |

| Excavated by | Howard Carter |

| Decoration | |

← Previous KV61 Next → KV63 | |

The tomb of young pharaoh Tutankhamun (designated KV62 in Egyptology) is located in the Valley of the Kings, near Thebes, Egypt (modern-day Luxor). It is renowned for the wealth of valuable antiquities that it contained.[1] Howard Carter discovered it in 1922 underneath the remains of workmen's huts built during the Ramesside Period; this explains why it was largely spared the desecration and tomb clearances at the end of the 20th Dynasty, although it was robbed and resealed twice in the period after its completion.

The tomb was densely packed with items in great disarray due to its small size, the two robberies, and the apparently hurried nature of its completion. It took eight years to empty due to the state of the tomb and to Carter's meticulous recording technique. The contents were all transported to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Tutankhamun's tomb had been entered at least twice not long after his mummy was buried. The outermost doors were unsealed leading into the shrines enclosing the king's nested coffins, though the inner two shrines remained intact and sealed.

Discovery of the tomb[]

Theodore M. Davis's team uncovered a small site containing funerary artifacts with Tutankhamun's name and some embalming parts in 1907, just before his discovery of the tomb of Horemheb. Davis erroneously assumed that this site was Tutankhamun's complete tomb and concluded the dig. The details of both findings are documented in his 1912 publication The Tombs of Harmhabi and Touatânkhamanou; the book closes with the comment, "I fear that the Valley of the Kings is now exhausted."[2]

Lord Carnarvon employed British Egyptologist Howard Carter to excavate the site of KV62, and in 1922 Carter returned to a line of huts that he had abandoned a few seasons earlier. The crew cleared the huts and rock debris beneath, and their young water boy, Hussein Abdel-Rassoul, stumbled on a stone which turned out to be the top of a flight of steps cut into the bedrock.[3][4] Carter had the steps partially dug out until the team found the top of a mud-plastered doorway. The doorway was stamped with indistinct cartouches (oval seals with hieroglyphic writing). Carter ordered the staircase to be refilled and sent a telegram to Carnarvon, who arrived on November 23, 1922 along with his 21-year-old daughter Lady Evelyn Herbert.[5]

The excavators cleared the stairway completely, which revealed clearer seals lower down on the door bearing the name of Tutankhamun. However, further examination showed that the door blocking had been breached and resealed on at least two occasions. Clearing the blocking led to a downward corridor that was completely blocked with packed limestone chippings, through which a robbers' tunnel had been excavated and anciently refilled. At the end of the tunnel was a second sealed door that had been breached and resealed in antiquity. Carter then made a hole in the door and used a candle to check for foul gases before looking inside. "At first I could see nothing," he wrote, "the hot air escaping from the chamber causing the candle flame to flicker, but presently, as my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues, and gold – everywhere the glint of gold."[6][7] After a pause, Carnarvon asked, "Can you see anything?" Carter replied, "Yes, wonderful things."[6]

Investigation[]

The official opening of the tomb took place on November 26, 1922,[8] with the first press report, in The Times, appearing on the 30th.[9] At this stage Carter had only one assistant, his friend Arthur Callender. Given the size and scope of the task ahead, Carter sought help from Albert Lythgoe of the Metropolitan Museum's excavation team, working nearby, who readily agreed to loan a number of his staff, including Arthur Mace and photographer Harry Burton, while the Egyptian government loaned analytical chemist Alfred Lucas.[10] Carter and his team began work in mid-December, and removed the first items—bead garments and sandals—from the tomb on December 27.[11] On February 16, 1923, the team opened the burial chamber.[12] On February 12, 1924, they raised the granite lid of the sarcophagus.[13] In February 1924 a dispute, caused by what Carter saw as excessive control by the Antiquities Service, led to a suspension of the excavation for nearly a year, with Carter leaving for a lecture tour in the United States.[14]

The Egyptian authorities eventually agreed that Carter should complete the tomb's clearance, and in January 1925 Carter returned. On October 13 the lid of the outermost coffin was removed. Carter opened the second coffin on October 23, and the team removed the lid of the innermost coffin on October 28, revealing the mummy.[15] They began examining the remains of Tutankhamun on November 11.[15] They began work in the treasury on October 24, 1926,[16] and emptied and examined the annex between October 30 and December 15, 1927.[17] They removed the last objects from the tomb on November 10, 1930, eight years after the discovery.[18]

The time taken to clear the tomb reflects Carter's methodical approach in carefully recording, assessing and cataloguing each item before its removal. This included photographing each item, both in the position found and individually, a task undertaken mainly by Harry Burton, loaned to Carter by the Metropolitan Museum's excavation team.[19]

Layout of the tomb[]

The essential plan and dimensions of KV62 are similar to those of private tombs of the period; however, its complexity is unparalleled.[20] It is thought that originally the tomb was designed for a non-royal personage[21] Howard Carter observed that by rotating the chamber 90 degrees, KV62 could be seen to resemble the typical royal ground plan for the 18th dynasty. The 90-degree rotation was likely a compromise that ancient tomb architects made when faced with the adaptation of a preexisting private tomb for royal use.[20]

Staircase[]

Sixteen steps descend from a small, level platform to the first doorway which was sealed and plastered, although it had been penetrated by grave robbers at least twice in antiquity.[5]

Entrance corridor[]

Beyond the first doorway, a descending corridor leads to the second sealed door and into the room that Carter described as the antechamber. This was used originally to hold material left over from the funeral, and material associated with embalming the king. After an initial robbery, this material was moved either into the tomb proper or to KV54, and the corridor was sealed with packed limestone chippings which covered some debris from the first robbery. A later robbery broke through the outer door and excavated a tunnel through the chippings to the second door. The robbery was discovered and the second door was resealed, the tunnel refilled, and the outer door sealed again.[22][23]

Some remnants in the corridor appear to have been from a funerary meal matching one discovered by Davis in jars in KV54, which indicates that KV54 may have been used as a store for items recovered after the first resealing of the tomb.[22][23] Carter said that he found the Head of Nefertem in this section.[24]

Antechamber[]

The undecorated antechamber was found in a state of "organized chaos", partly due to ransacking during the robberies. It contained approximately 700 objects (articles 14 to 171 in the Carter catalogue) among which were three funeral beds, one in the form of a lion (the goddess Sekhmet), one in the shape of a spotted cow (representing Mehet-Weret), and one the form of a composite animal with the body of a lion, the tail of a hippopotamus, and the head of a crocodile (representing the corpse-devourer Ammit). Perhaps the most remarkable item in this room were the stacked components of four chariots, one of which was possibly used for hunting, one for war, and another two for parades. A large chest was found to contain military items, walking sticks, the king's underwear, and a copper alloy trumpet, one of two found in the tomb and the oldest known functioning brass instruments in the world.[25][26]

Burial chamber[]

Decoration[]

This is the only decorated chamber in the tomb, with scenes from the opening of the mouth ceremony (showing Ay, Tutankhamun's successor acting as the king's son, despite being older than he is) and Tutankhamun with the goddess Nut on the north wall, the twelve hours of Amduat (on the west wall), spell one of the Book of the Dead (on the east wall) and representations of the king with various deities (Anubis, Isis, Hathor and others now destroyed) on the south wall. The north wall shows Tutankhamen being followed by his Ka, being welcomed to the underworld by Osiris.[27]

Some of the treasures in Tutankhamun's tomb are noted for their apparent departure from traditional depictions of the boy king. Certain cartouches where a king's name should appear have been altered, as if to reuse the property of a previous pharaoh, as has often occurred. However, this instance may simply be the product of "updating" the artifacts to reflect the shift from Tutankhaten to Tutankhamun. Other differences are less easy to explain, such as the older, more angular facial features of the middle coffin and canopic coffinettes. The most widely accepted theory for these latter variations is that the items were originally intended for Smenkhkare, who may or may not be the mysterious KV55 mummy. This mummy, according to craniological examinations, bears a striking first-order (father-to-son, brother-to-brother) relationship to Tutankhamun.[28]

Contents[]

The entire chamber was occupied by four gilded wooden shrines which surrounded the king's sarcophagus. The outer shrine measured 5.08 × 3.28 × 2.75 m and 32 mm thick, almost entirely filling the room, with only 60 cm at either end and less than 30 cm on the sides. Outside of the shrines were 11 paddles for the "solar boat", containers for scents, and lamps decorated with images of the god Hapi. The fourth and innermost shrine was 2.90 m long and 1.48 m wide. The wall decorations depict the king's funeral procession, and Nut was painted on the ceiling, "embracing" the sarcophagus with her wings.[citation needed]

This sarcophagus was constructed in quartzite with a lid of rose granite tinted to match.[29] It appears to have been constructed for another owner, but then recarved for Tutankhamun; the identity of the original owner is not preserved.[27] In each corner a protective goddess (Isis, Nephthys, Serket and Neith) guards the body.[citation needed]

Inside, the king's body was placed within three mummiform coffins, the outer two made of gilded wood while the innermost was composed of 110.4 kilograms (243 lb) of pure gold.[30][31][a] Tutankhamun's mummy was adorned with a gold mask, mummy bands and other funerary items. The funerary mask is made of gold, inlaid with lapis lazuli, carnelian, quartz, obsidian, turquoise and glass and faience, and weighs 11 kilograms (24 lb).[33]

Funerary text[]

The Enigmatic Book of the Netherworld is a two-part ancient Egyptian funerary text inscribed on the second shrine of the sarcophagus. The term "enigmatic" here refers to it being written in cryptographic code, a New Kingdom practice also known from the tombs of Ramesses IX and Ramesses V. Its content is therefore not readily available to Egyptology; Coleman (2004) interprets it in terms of the creation and rebirth of the sun. The text is broken into three sections that incorporate other funerary texts, such as the Book of the Dead and the Amduat.[34][35] The text is notable for containing the first known depiction of the ouroboros symbol, in the form of two serpents (interpreted as manifestations of the deity Mehen) encircling the head and feet of a god, taken to represent the unified Ra-Osiris.[36]

Treasury[]

The treasury was the burial chamber's only side-room and was accessible by an unblocked doorway. It contained over 5,000 catalogued objects, most of them funerary and ritual in nature. The two largest objects found in this room were the king's elaborate canopic chest and a large statue of Anubis: Anubis Shrine. Other items included numerous shrines containing gilded statuettes of the king and deities, model boats and two more chariots. This room also held the mummies of two fetuses[37] that DNA testing has shown to have been stillborn offspring of the king.[38]

Annex[]

The annex, originally used to store oils, ointments, scents, foods and wine, was the last room to be cleared, from the end of October 1927 to the spring of 1928. Although small in size, it contained approximately 280 groups of objects, totaling more than 2,000 individual pieces. Also found within the annex chamber were 26 jars containing wine residue.[39][40]

Robberies[]

During the excavation it quickly became apparent that the tomb had been robbed in ancient times. The upper part of the door leading into the tomb had been damaged and repaired, with the symbol of the Royal Necropolis affixed. Behind it was a corridor carved through the bedrock filled with limestone chippings, which seemed to have been tunnelled through. A second door had also been penetrated and repaired at some point. Parts of absent objects and traces of oils in empty jars led Carter to conclude that the tomb had been raided for gold shortly after Tutankhamun's burial, and again for expensive oils.[23]

The corridor had presumably been filled with debris after the first robbery, as the inner plaster door lacked the marking of the chippings that the repaired area demonstrated, indicating that it had dried before its placement. This debris had been tunneled through in a later robbery. The chippings also covered some fragments of looted articles including jar lids, razors and wood fragments that had been presumably removed from the antechamber and stored in the tunnel during the first robbery.[22][23]

Two sealed chambers leading from the antechamber—the annex and the burial chamber—had also been raided.[41] The annex was probably the worst affected by the first robbery.[22] The room was small and full of densely packed items, which had been ransacked by a robber who had entered through a small hole in the outer door. The robber hurriedly disturbed the contents of the annex, emptied boxes and removed items. The robbers seem to have been looking for metals, glass (then a valuable commodity), cloth, oils and cosmetics. The robbery was fairly contemporary with the burial, as the lifespan of oils and cosmetics would have been limited. After this robbery was discovered, the doors were resealed and it is likely that the descending tunnel was filled with packed limestone chippings to deter future robberies.[22]

The second robbery required much more organisation to clear the descending corridor—a tunnel was dug in the top-left-hand corner of the tunnel, and the outer door was penetrated by a large hole in the blocking. Carter estimated that it would have taken a team of men around eight hours to excavate the tunnel by passing back baskets of rubble. The second robbery penetrated the entire tomb, and Carter estimated that around 60% of the jewelry in the treasury had been looted, along with precious metals. At some point, a knotted scarf containing a number of looted rings was dropped back into a box in the antechamber, which led Carter to the conclusion that the robbery had perhaps been discovered while it was in progress, or that the thieves had been pursued and caught.[22]

The tomb may have been hurriedly resealed (possibly to avoid drawing attention to the tomb) by the official Maya, as the signature of his assistant Djehutymose was found by Carter on a calcite stand in the annex. Upon resealing the tomb, the first and second resealings were marked with the same seal, bearing a design of a jackal over nine bound captives, which may indicate that they both took place within a short time interval after the closure of the tomb.[22][42]

Possible undiscovered chambers[]

Research by Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves (attached to the University of Arizona) suggested, in 2015, that there may be areas of the tomb worthy of further analysis. Reeves investigated high-resolution digital scans of the tomb taken by Madrid-based company Factum Arte that were used in the process of creating a facsimile of the tomb. Reeves noted markings in the plaster of the burial chamber that appeared to suggest the possibility of a small door in the west wall of the burial chamber, of the same dimensions as the annex door. According to Reeves, markings on the north wall could also suggest that the wall itself may partly be a blocking wall covering a void, possibly indicating that the "antechamber" continues as a corridor beyond the north wall. Although the "doors" may just be uncompleted construction work, one possibility that has been suggested is that Tutankhamun is actually buried in the outer section of a larger tomb complex (similar to the tomb of Amenhotep III) that has been sealed off by the north wall, and that a further burial (possibly that of Nefertiti) may exist elsewhere in undiscovered areas of the tomb.[43]

In November 2015, a ground-penetrating radar scan was conducted by Hirokatsu Watanabe, a Japanese radar expert. His results appeared to confirm Reeves' hypothesis, indicating that there were voids behind the west and north walls of the burial chamber.[44] A second GPR scan could not replicate Watanabe's findings. A third scan was carried out by researchers from the Polytechnic University of Turin, the University of Turin, and two private companies, which found no evidence of any hidden chambers, thereby disproving Reeves' hypothesis.[45][46] They concluded that the initial positive result was likely caused by reflections of the walls themselves, or even interference from the sarcophagus.[47] The Egyptian Ministry of State of Antiquities reviewed and accepted these results, which were presented in May 2018.[48][49]

Nicholas Reeves, in 2019, reviewed and extended his original hypothesis, including a review of the available geophysical data by geophysicist and radar expert George Ballard.[50] This includes not only the three radar scans, but correlates these with the ERT results published earlier by the same research team from the Polytechnic University of Turin and the University of Turin. Ballard agreed that no open chambers or spaces had been located immediately behind the walls, but observed that the radar data from the zone behind the North and Treasury walls was more consistent with a rubble fill, indicative of a possible anthropic origin, rather than natural rock. The location in the ERT data of two isolated resistivity anomalies consistent with voided spaces, close to the same level as KV 62, but separated from it, raises the possibility that there is a back filled passageway behind the walls leading to further chambers. This analysis is supportive of Reeves' original hypothesis, and contradicts the conclusion, accepted previously by the Ministry of Antiquities, drawn by Porcelli et al.[51]

Meteorite dagger[]

A 2016 study suggested that the dagger buried with Tutankhamun was made from an iron meteorite, with similar proportions of metals (iron, nickel and cobalt) to one discovered near and named after Kharga Oasis.[52]

Present day[]

The tomb is open to the public at an additional charge to that of general admission to the Valley of the Kings. The number of visitors was limited to 400 per day in 2008.[53] A project for the conservation and management of the tomb was undertaken by the Getty Conservation Institute.[54] In 2009, the Factum Foundation for Digital Technology in Conservation began work on a replica of the tomb, which was opened about a mile from the original in 2014.[55][56] The Getty Conservation Institute completed its work in 2019, marking the most significant conservation project on the tomb to date.[57]

See also[]

- Curse of the pharaohs

- Lotus chalice

- Of Time, Tombs and Treasures, a 1977 documentary film about the discovery of KV62

- Tutankhamun's trumpets

References[]

Footnotes

Citations

- ^ "Tutankhamun". University College London. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ Davis, Theodore M. (2001). The Tombs of Harmhabi and Touatânkhamanou. London: Duckworth Publishing. ISBN 0-7156-3072-5.

- ^ Christianson, Scott (November 5, 2015). "A Look Inside Howard Carter's Tutankhamun Diary". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved July 6, 2018.

- ^ Dabrowska, Karen (12 January 2020). "Tutankhamun still draws large crowds in London". The Arab Weekly. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ^ a b Winstone 2006, p. 142.

- ^ a b Gilbert, Holt & Hudson 1976, p. 13.

- ^ "The Tombs of Tutankhamun and his Predecessor". Archived from the original on 2015-09-25. Retrieved 2015-09-24.

- ^ Carter, Howard; Mace, Arthur Cruttenden (2019-09-17). The Discovery of Tutankhamun's Tomb: Illustrated Edition. e-artnow. ISBN 978-80-273-0329-8.

- ^ Macintyre, Ben. "How The Times dug up a Tutankhamun scoop and buried its Fleet Street rivals". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- ^ Winstone 2006, pp. 155–161.

- ^ "A. C. Mace's personal diary of the first excavation season (December 27, 1922 to May 13, 1923)". Archived from the original on June 30, 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- ^ "Howard Carter's diaries (January 1 to May 31, 1923)". Archived from the original on 2007-04-07. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- ^ "Howard Carter's diaries (October 3, 1923 to February 11, 1924)". Archived from the original on 2007-04-07. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- ^ Bill Price (2009). Tutankhamun, Egypt's Most Famous Pharaoh. Hertfordshire: Published Pocket Essentials. pp. 132–134. ISBN 978-1842432402.

- ^ a b Carter, Howard. "Excavation Journal 4th Season, September 28th 1925 to May 21st 1926". www.griffith.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ Carter, Howard. "Excavation Journal 5th Season, September 22nd 1926 to May 3rd 1927". Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ Carter, Howard. "Excavation Journal 6th Season, October 8th 1927 to April 26th 1928".

- ^ "Howard Carter's diaries (September 24 to November 10, 1930)". Archived from the original on June 30, 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- ^ Ridley, Ronald T. The Dean of Archaeological Photographers: Harry Burton Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 99, 2013. California: SAGE Publishing. pp. 124–126.

- ^ a b Reeves, Nicholas; Wilkinson, Richard H. (2008). The Complete Valley of the Kings – Tombs and Treasures of Egypt's Greatest Pharaohs. New York: Thames & Hudson. p. 1245. ISBN 978-0500284032.

- ^ "KV 62 (Tutankhamen)". Archived from the original on 2007-12-12. Retrieved December 31, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Andrews, Mark (2006). "The King Tut Tomb Robberies". Archived from the original on 9 February 2006. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d Gilbert, Holt & Hudson 1976, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Zahi Hawass: King Tutankhamun. The Treasures Of The Tomb. p. 16.

- ^ Finn, Christine (2011-04-17). "Recreating the sound of Tutankhamun's trumpets". BBC News. Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- ^ "Ghost Music". BBC Radio 4 Programmes. Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- ^ a b "KV 62 (Tutankhamen): Burial chamber J". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ Reeves & Wilkinson 1995.

- ^ Carter, Howard (1927). The Tomb of Tutankhamen Volume II. London: Cassel and Company, LTD. pp. 48–49.

- ^ Gilbert, Holt & Hudson 1976, p. 5.

- ^ "The Innermost Coffin of Tutankhamun". Eternal Egypt. 2005. Archived from the original on January 1, 2019. Retrieved January 1, 2019.

- ^ Carter, Howard (2014). The Tomb of Tutankhamun: Volume 2: The Burial Chamber. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-4725-7764-1.

- ^ Alessandro Bongioanni & Maria Croce (ed.), The Treasures of Ancient Egypt: From the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Universe Publishing, a division of Ruzzoli Publications Inc., 2003. p. 310

- ^ Darnell, John Coleman (2004). The Enigmatic Netherworld Books of the Solar-Osirian Unity. Academic Press Fribourg / Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Göttingen. ISBN 3-7278-1469-1, 3-525-53055-2.

- ^ Hornung 1999, pp. 77–82.

- ^ Hornung 1999, pp. 38, 77–78.

- ^ Carter, Howard. The Tomb of Tutankhamen, 1972 ed, Barrie & Jenkins, p. 189, ISBN 0-214-65428-1

- ^ Hawass, Z.; Gad, Y. Z.; Ismail, S.; Khairat, R.; Fathalla, D.; Hasan, N.; Ahmed, A.; Elleithy, H.; Ball, M.; Gaballah, F.; Wasef, S.; Fateen, M.; Amer, H.; Gostner, P.; Selim, A.; Zink, A.; Pusch, C. M. (2010). "Ancestry and pathology in King Tutankhamun's family". JAMA. 303 (7): 638–47. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.121. PMID 20159872. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- ^ Ancient Egyptian materials and technology. Nicholson, Paul T.; Shaw, Ian. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2000. ISBN 0521452570. OCLC 38542531.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Gately, Iain (2008). Drink. Gotham Books. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-592-40303-5.

- ^ Gilbert, Holt & Hudson 1976, p. 15.

- ^ Bohleke, Briant (2002). "Amenemopet Panehsi, Direct Successor of the Chief Treasurer Maya". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 39: 157–172. doi:10.2307/40001153. JSTOR 40001153.

- ^ Reeves, Nicholas. "The burial of Nefertiti ?". Retrieved 2015-09-24.

- ^ "Radar Scans in King Tut's Tomb Suggest Hidden Chambers". National Geographic News. 28 November 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ "It's Official: Tut's Tomb Has No Hidden Chambers After All". National Geographic News. 6 May 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ Sambuelli, Luigi; Comina, Cesare; Catanzariti, Gianluca; Barsuglia, Filippo; Morelli, Gianfranco; Porcelli, Francesco (May 2019). "The third KV62 radar scan: Searching for hidden chambers adjacent to Tutankhamun's tomb". Journal of Cultural Heritage. 39: 8. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2019.04.001. S2CID 164859865.

- ^ Sambuelli, Luigi; Comina, Cesare; Catanzariti, Gianluca; Barsuglia, Filippo; Morelli, Gianfranco; Porcelli, Francesco (May 2019). "The third KV62 radar scan: Searching for hidden chambers adjacent to Tutankhamun's tomb". Journal of Cultural Heritage. 39: 9. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2019.04.001. S2CID 164859865.

- ^ "Tutankhamun 'secret chamber' does not exist, researchers find". BBC. May 6, 2018. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ^ "King Tut's tomb not concealing hidden rooms after all". Associated Press. May 6, 2018. Retrieved May 6, 2018 – via NBC News.

- ^ Reeves, Nicholas; Ballard, George (2019). "The Decorated North Wall in the Tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62) (The Burial of Nefertiti? II)". Amarna Royal Tombs Project Occasional Paper No.3: 1–22. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ Reeves, Nicholas; Ballard, George (2019). "The Decorated North Wall in the Tomb of Tutankhamun (KV62) (The Burial of Nefertiti? II)". Amarna Royal Tombs Project Occasional Paper No.3: 13–22. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ King Tutankhamun buried with dagger made of space iron, study finds, ABC News Online, 2 June 2016

- ^ "400 visitors to Tutankhamun's tomb". Egypt State Information Service. Archived from the original on 2007-11-24. Retrieved 2007-11-13.

- ^ "Conservation and Management of the Tomb of Tutankhamen". Retrieved 2013-11-17.

- ^ Del Giudice, Marguerite (20 May 2014). "Tut's Tomb: A Replica Fit for a King". National Geographic. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ "Tutankhamon Tomb recreation". Euronews. Archived from the original on 27 November 2012. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ^ "King Tut's tomb unveiled after being restored to its ancient splendor". CBS News. 2 February 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

Sources[]

- Hornung, Erik (1999). The Ancient Egyptian Books of the Afterlife (in German). David Lorton (translator). Cornell University Press.

- Gilbert, Katherine Stoddert; Holt, Joan K.; Hudson, Sara, eds. (1976). Treasures of Tutankhamun. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-87099-156-6.

- Reeves, Nicholas C.; Wilkinson, Richard H. (1995) [1990]. The Complete Tutankhamun: The King, the Tomb, the Royal Treasure. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0500278109.

- Reeves, Nicholas; Wilkinson, Richard H. (1996). The Complete Valley of the Kings. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Winstone, H.V.F. (2006). Howard Carter and the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun. Barzan, Manchester. ISBN 1-905521-04-9. OCLC 828501310.

Further reading[]

- Carter, Howard & Mace, Arthur C. The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamen.

- Siliotti, A. Guide to the Valley of the Kings and to the Theban Necropolises and Temples, 1996, A.A. Gaddis, Cairo.

- Marchant, Jo (2013). The Shadow King: The Bizarre Afterlife of King Tut's Mummy. Da Capo Press.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to KV62. |

- Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation Griffith Institute

- High-resolution image viewer of the tomb by

- KV62: Tutankhamen at the Theban Mapping Project

- 1922 archaeological discoveries

- Buildings and structures completed in the 14th century BC

- Valley of the Kings

- Tutankhamun