Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold

Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold | |

|---|---|

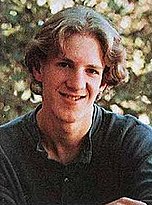

Harris (left) and Klebold in their senior year pictures, 1999 | |

| Born | Eric David Harris April 9, 1981 Wichita, Kansas, U.S. Dylan Bennet Klebold September 11, 1981 Lakewood, Colorado, U.S. |

| Died | April 20, 1999 (aged 18 and 17) Columbine, Colorado, U.S. (both)[1] |

| Cause of death | Suicide by self-inflicted gunshot wound (both) |

| Alma mater | Columbine High School (both) |

| Occupation | Harris: Shift leader at Blackjack Pizza Klebold: Cook at Blackjack Pizza |

| Parent(s) | Harris: Wayne Harris and Katherine Poole Klebold: Thomas Klebold and Susan Yassenoff |

| Details | |

| Date | April 20, 1999 11:19 a.m. – 12:08 p.m. MDT (UTC−6) |

| Location(s) | Columbine High School |

| Target(s) | Students and staff at Columbine High School; and first responders |

| Killed | 15 (total); 9 by Harris (including himself) and 6 by Klebold (including himself) |

| Injured | 24 (3 indirectly; combined total) |

| Weapons | Harris: Hi-Point 995 Carbine, Savage 67H pump-action shotgun, explosives and two knives Klebold: Intratec TEC-DC9, Stevens 311D double barreled sawed-off shotgun, explosives and two knives[a] |

| Part of a series of articles on the |

| Columbine massacre |

|---|

|

| Related articles |

|

Eric David Harris (April 9, 1981 – April 20, 1999) and Dylan Bennet Klebold (/ˈkliːboʊld/; September 11, 1981 – April 20, 1999) were an American mass murder duo who perpetrated the Columbine High School massacre. Harris and Klebold killed 13 people and wounded 24 others[b] on April 20, 1999, at Columbine High School, where they were seniors, in Columbine, Colorado. After killing most of their victims in the school's library, they simultaneously committed suicide. At the time, it was the deadliest high school shooting in U.S. history,[c] with the ensuing media frenzy and moral panic leading it to become one of the most infamous mass shootings ever perpetrated in the US.

Harris and Klebold met while they were in the 7th grade. Over time, they became increasingly close. By the time they were juniors, they were described as inseparable. There are differing reports: some say Harris and Klebold were very unpopular students and frequent targets of bullying, while others say they were not near the bottom of the school's social hierarchy and each had many friends. From their journals, Harris and Klebold had seemed to begin planning the attack a year prior. Throughout the next year, Harris and Klebold meticulously built explosives and gathered an arsenal of weapons. Harris and Klebold left behind several journal writings and home videos, foreshadowing the massacre and explaining their actions, with what they hoped to achieve.

After the massacre, it was widely believed Harris and Klebold were part of a clique in school called the "Trenchcoat Mafia", a group of misfits in the school who supposedly rebelled against the popular students.[3] This turned out to be untrue, as neither Harris nor Klebold had any affiliation with the group.[4][5] The pair's aforementioned writings and videos gave insight into their rationale for the shooting. The FBI concluded that Harris was a psychopath, who exhibited a lack of empathy, narcissistic traits and unconstrained aggression. Klebold, however, was concluded to be an angry depressive, who showed low self-esteem, anxiousness and a vengeful attitude toward individuals who he believed had mistreated him.[6] However, neither Harris nor Klebold were formally diagnosed with any mental illnesses prior to the attack.[7] In the following years, various media outlets attributed multiple motivating factors to the attack, including bullying, mental illness, racism, psychiatric medication and media violence. Despite these conclusions, the exact motive for the attack remains inconclusive.

Harris and Klebold have become pop culture icons, with the pair often portrayed, referenced and seen in film, television, video games, music and books. Many killers since the shooting have taken inspiration from the pair, either hailing them as heroes, martyrs and gods, or expressing sympathy for the pair. Harris and Klebold also have a fanbase, who have coined the term "Columbiners", who write fan fiction and draw fan art of them. Others have also dressed as the duo for cosplay or Halloween.[8]

Early life

Eric Harris

Eric David Harris was born on April 9, 1981, in Wichita, Kansas. Harris's parents were both born and raised in Colorado. His mother, Katherine Ann Poole, was a homemaker. His father, Wayne Harris, was working in the United States Air Force as a transport pilot, forcing the family to move around the country sporadically. In 1983, the family moved to Dayton, Ohio, when Harris was two years old. Six years later, the family relocated to Oscoda, Michigan. The Harris family moved to Plattsburgh, New York, in 1992, then to Colorado the next year when Wayne retired from the military.[9] Kyle Ross, a former classmate of Harris, said, "He was just a typical kid."[10]

On a 1997 English class assignment, Harris wrote about how difficult the move was from New York to Colorado. "It was the hardest moving from Plattsburgh. I have the most memories from there," Harris continued. "When I left (his friends) I felt alone, lost and even agitated that I had spent so much time with them and now I have to go because of something I can't stop."[11] Harris, in a basement tape, blamed his father for moving the family around, forcing Harris to "start out at the bottom of the ladder."[12] Harris also added that kids would often mock his appearance.

The Harris family lived in rented accommodations for the first three years that they lived in the Littleton area. While Harris was in 7th grade, he met Klebold. In 1996, the Harris family purchased and settled at a house south of Columbine High School. Harris' older brother, Kevin, attended college at the University of Colorado.[13][14] Harris' father took a job with Flight Safety Services Corporation and Harris' mother, a former homemaker, became a caterer.[15][16]

Harris entered Columbine High School in 1995 as a freshman. Columbine had just gone through a major renovation and expansion.[17] From all accounts, he had many friends and was left forward and mid-field on the Columbine soccer team for his freshman and sophomore year. According to one of his teammates, Josh Swanson, he said Harris was a "solid" soccer player, who enjoyed the sport a lot.[18][19] Harris, during his freshman year, met Tiffany Typher, who was in his German class.[20] Typher later recounted that Harris quickly wooed her. Harris asked her to homecoming and she accepted. After the event, it appeared that Typher was no longer interested in seeing Harris anymore, for reasons never disclosed. When Typher refused to socialize with Harris again, Harris staged a fake suicide, sprawling on the ground with fake blood splashed all over him. When Typher saw him she began to scream for help, at which point Harris and his friends began laughing, prompting Typher to storm off, shouting at Harris to get psychological help.[21]

Dylan Klebold

Dylan Bennet Klebold was born on September 11, 1981, in Lakewood, Colorado, to Thomas and Sue Klebold.[9] On the day after the shooting, Klebold's mother remembered that shortly after Klebold's birth, she described what felt like a shadow had been cast over her, warning her that this child would bring her great sorrow. "I think I still make of it what I did at that time. It was a passing feeling that went over very quickly, like a shadow." Sue said in an interview with Colorado Public Radio. Klebold was soon diagnosed with pyloric stenosis, a condition in which the opening between the stomach and small intestines thickens, causing severe vomiting during the first few months of life. Sue later assured herself that the feeling she had that her son would bring her immense sorrow, was that her son would be physically ill.[22]

Klebold's parents had met when they were both studying art at Ohio State University. The two quickly became smitten. After they both graduated, they married in 1971, with their first child, Byron, being born in 1978. Thomas had initially worked as a sculptor, but then moved over to engineering to be more financially stable.[23] Sue had worked in assistance services with disabled children. Furthermore, Klebold's parents were pacifists and attended a Lutheran church with their children. Both Klebold and his older brother attended confirmation classes in accordance with the Lutheran tradition.[24] As had been the case with his older brother, Klebold was named after a renowned poet, Dylan Thomas.[25]

At the family home, the Klebolds also observed some rituals in keeping with Klebold's maternal grandfather's Jewish heritage.[24][26] Klebold attended Normandy Elementary School for first and second grade and then transferred to Governor's Ranch Elementary School where he was part of the Challenging High Intellectual Potential Students program for gifted children. According to reports, Klebold was exceptionally bright as a young child, although he appeared somewhat sheltered in elementary school.[27] When he transitioned to Ken Caryl Middle School, he found it difficult. Klebold's parents were unconcerned with the fact that Klebold found the changing of schools uneasy, as they assumed it was just regular behavior among young adolescents.[28]

During his earlier school years, Klebold played baseball, soccer and T-ball. Klebold was in Cub Scouts with friend Brooks Brown, whom he was friends with since the first grade. Brown lived near the house Harris' parents had bought when they finally settled in Littleton, and rode the same bus as Harris. Shortly after, Klebold had met Harris and the pair quickly became best friends. Later, Harris introduced Klebold to his friend Nathan Dykeman, who also attended their middle school, and they all became a tight-knit group of friends.[29]

Background

Personalities

Both Harris and Klebold worked together as cooks at a Blackjack Pizza, a mile south from Columbine High School. Harris was eventually promoted to shift leader.[30] He and his group of friends were interested in computers,[31] and were enrolled in a bowling class.[32]

Some described Harris as charismatic, and others described him as nice and likable.[33][34] However, Harris also often bragged about his ability to deceive others, once stating in a tape that he could make anyone believe anything.[35] By his junior year, Harris was also known to be quick to anger, and threatened people with bombs.[33][36] Classmates also related that Harris was fascinated by war, and wrote out violent fantasies about killing people he didn't like.[34]

Klebold was described by his peers and adults as painfully shy. Klebold would often be fidgety whenever someone new talked to him, rarely opening up to people.[37]

Friendship

Much of the information on Harris and Klebold's friendship is unknown, on their interactions and conversations, aside from the Basement Tapes, of which only transcripts have been released. Harris and Klebold met at Ken Caryl Middle School during their seventh grade year. Over time, they became increasingly close, hanging out by often going out bowling, carpooling and playing the video game Doom over a private server they connected their personal computers to. By their junior year in high school, the boys were described as inseparable. Chad Laughlin, a close friend of Harris and Klebold, said that they always sat alone together at lunch and often kept to themselves.[38]

A rumor eventually started that Harris and Klebold were gay and romantically involved, due to the time the pair spent together. It is unknown if they were aware of this rumor.[39] Although, a friend of the pair, Chad Laughlin, reported that both Harris and Klebold died virgins.[40] Judy Brown believed Harris was more emotionally dependent on Klebold, who was more liked by the broader student population.[41] In his journals, however, Klebold wrote that he felt that he was not accepted or loved by anyone. Due to these feelings, Klebold possibly sought validation from Harris. Klebold's mother believes Harris' rage, intermingled with Klebold's self-destructive personality, caused the boys to feed off of each other and enter in what eventually would become an infernal friendship.[42]

Columbine High School

At Columbine High School, Harris and Klebold were active in school play productions, operated video productions and became computer assistants, maintaining the school's computer server.[9] According to early accounts of the shooting, they were very unpopular students and targets of bullying. While sources do support accounts of bullying specifically directed toward Harris and Klebold,[43][44][45] accounts of them being outcasts have been reported to be false, since both of them had a close knit group of friends.[46][47]

Harris and Klebold were initially reported to be members of a clique that was called the "Trenchcoat Mafia," despite later confirmation that the pair had no connection to the group and furthermore did not appear in the group's photo in Columbine High's 1998 yearbook.[48][49] Harris' father erroneously stated that his son was "a member of what they call the Trenchcoat Mafia" in a 9-1-1 call he made on April 20, 1999.[50] Klebold attended the high school prom three days before the shootings with a classmate named Robyn Anderson.[51]

Harris and Klebold linked their personal computers on a network and played video games over the Internet. Harris created a set of levels for the game Doom, which later became known as the 'Harris levels'. The levels are downloadable over the internet through Doom WADs. Harris had a web presence under the handle "REB" (short for Rebel, a nod to the nickname of Columbine High's sports teams) and other online aliases, including "Rebldomakr", "Rebdoomer", and "Rebdomine". Klebold went by the names "VoDKa" and "VoDkA", seemingly inspired by the alcoholic drink. Harris had various websites that hosted Doom and Quake files, as well as team information for those with whom he gamed online. The sites openly espoused hatred for people in their neighborhood and the world in general. When the pair began experimenting with pipe bombs, they posted results of the explosions on the websites. The website was shut down by America Online after the shootings and was preserved for the FBI.[52]

Initial legal encounters

On January 30, 1998, Harris and Klebold broke into a locked van to steal computers and other electronic equipment. An officer pulled over the duo driving away. Harris shortly after admitted to the theft. They were later charged with mischief, breaking and entering, trespassing, and theft. They both left good impressions on juvenile officers, who offered to expunge their criminal records if they agreed to attend a diversionary program which included community service and psychiatric treatment. Harris was required to attend anger management classes where, again, he made a favorable impression. The boys' probation officer discharged them from the program a few months ahead of schedule for good behavior. Of Harris, it was remarked that he was "a very bright individual who is likely to succeed in life", while Klebold was said to be intelligent, but "needs to understand that hard work is part of fulfilling a dream."[53] A couple of months later on April 30, Harris handed over the first version of a letter of apology he wrote to the owner of the van, which he completed the next month.[54] In the letter, Harris expressed regret about his actions; however, in one of his journal entries dated April 12, he wrote: "Isn't america supposed to be the land of the free? how come, If im free, I cant deprive some fucking dumbshit from his possessions If he leaves them sitting in the front seat of his fucking van in plain sight in the middle of fucking nowhere on a fri-fucking-day night? Natural selection. Fucker should be shot. [sic]".[55][56]

Hitmen for Hire

In December 1998, Harris and Klebold made Hitmen for Hire, a video for a school project in which they swore, yelled at the camera, made violent statements, and acted out shooting and killing students in the hallways of Columbine High School.[57] Both also displayed themes of violence in their creative writing projects; of a Doom-based story written by Harris on January 17, 1999, Harris' teacher said: "Yours is a unique approach and your writing works in a gruesome way — good details and mood setting."[58][59]

Acquiring arms

Harris and Klebold were unable to legally purchase firearms due to them both being underage at the time. Klebold then enlisted Robyn Anderson, an 18-year-old Columbine student and old friend of Klebold's, to make a straw purchase of two shotguns and a Hi-Point carbine for the pair. In exchange for her cooperation with the investigation that followed the shootings, no charges were filed against Anderson.[60] After illegally acquiring the weapons, Klebold sawed off his Savage 311-D 12-gauge double-barrel shotgun, shortening the overall length to approximately 23 inches (580 mm). Meanwhile, Harris's Savage-Springfield 12-gauge pump shotgun was sawn off to around 26 inches (660 mm).[61]

The shooters also possessed a TEC-DC9 semi-automatic handgun, which had a long history. The manufacturer of the TEC-DC9 first sold it to Miami-based Navegar Incorporated. It was then sold to Zander's Sporting Goods in Baldwin, Illinois, in 1994. The gun was later sold to Thornton, Colorado firearms dealer, Larry Russell. In violation of federal law, Russell failed to keep records of the sale, yet he determined that the purchaser of the gun was twenty-one years of age or older. Two men, Mark Manes and Philip Duran, were convicted of supplying weapons to the two.[62]

The bombs used by the pair varied and were crudely made from carbon dioxide canisters, galvanized pipe, and metal propane bottles. The bombs were primed with matches placed at one end. Both had striker tips on their sleeves. When they rubbed against the bomb, the match head would light the fuse. The weekend before the shootings, Harris and Klebold had purchased propane tanks and other supplies from a hardware store for a few hundred dollars. Several residents of the area claimed to have heard glass breaking and buzzing sounds from the Harris family's garage, which later was concluded to indicate they were constructing pipe bombs.[63]

More complex bombs, such as the one that detonated on the corner of South Wadsworth Boulevard and Ken Caryl Avenue, had timers. The two largest bombs built were found in the school cafeteria and were made from small propane tanks. Only one of these bombs went off, only partially detonating.[9] It was estimated that if any of the bombs placed in the cafeteria had detonated properly, the blast could have caused extensive structural damage to the school and would have resulted in hundreds of casualties.[64]

Massacre

On April 20, 1999, just weeks before Harris and Klebold were both due to graduate,[65] Brooks Brown, who was smoking a cigarette outside during lunch break, saw Harris arrive at school. Brown had severed his friendship with Harris a year earlier after Harris had thrown a chunk of ice at his car windshield; Brown reconciled with Harris just prior to the shooting. Brown approached Harris near his car and scolded him for skipping his morning classes, because Harris was always serious about schoolwork and being on time. Harris replied, "It doesn't matter anymore." Harris followed up a few seconds later, "Brooks, I like you now. Get out of here. Go home."[66] Brown, who felt uneasy, quickly left the school grounds. At 11:19 am, he heard the first gunshots after he had walked some distance away from the school, and informed the police via a neighbor's cell phone.[67]

By that time, Klebold had already arrived at the school in a separate car, and the two boys left two gym bags, each containing a 20-pound propane bomb, inside the cafeteria. Their original plans indicated that when these bombs detonated, Harris and Klebold would be camped out by their cars and shoot, stab and throw bombs at survivors of the initial explosion as they ran out of the school. At noon, this would be followed by bombs set up in the pair's cars detonating, killing first responders and other personnel.[68] When these devices failed to detonate, Harris and Klebold launched a shooting attack against their classmates and teachers. It was the deadliest attack ever perpetrated at an American high school until the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting on February 14, 2018.[69][70] Harris was responsible for eight of the thirteen confirmed deaths (Rachel Scott, Daniel Rohrbough,[71] teacher Dave Sanders, Steve Curnow, Cassie Bernall, Isaiah Shoels, Kelly Fleming, and Daniel Mauser), while Klebold was responsible for the remaining five (Kyle Velasquez, Matthew Kechter, Lauren Townsend, John Tomlin, and Corey DePooter). There were 24 injured (21 of them by the shooters), most in critical condition.[72][73]

Suicide

At 12:02 pm, Harris and Klebold returned to the library. Of the 56 library hostages, 34 remained unharmed, all of whom escaped after Harris and Klebold left the library initially. Investigators would later find that Harris and Klebold had enough ammunition to have killed them all.[74] This was 20 minutes after their lethal shooting spree had ended, leaving 12 students dead, one teacher dying, and another 24 students and staff injured. Ten of their victims had been killed in the library.[75] It is believed they came back to the library to watch their car bombs detonate, which had been set up to explode at noon.[75] This did not happen, as the aforementioned bombs failed. Harris and Klebold went to the west windows and opened fire on the police outside. No one was injured in the exchange. Between three and six minutes later, they walked to the bookshelves near a table where Patrick Ireland lay badly wounded and coming in and out of consciousness. Student Lisa Kreutz, injured in the earlier library attack, was also in the room, unable to move.[76]

By 12:08 pm, Harris and Klebold had killed themselves. In a subsequent interview, Kreutz recalled hearing a comment such as, "You in the library," around this time. Harris sat down with his back to a bookshelf and fired his shotgun through the roof of his mouth; Klebold went down on his knees and shot himself in the left temple with his TEC-9. An article by The Rocky Mountain News stated that Patti Nielson overheard them shout "One! Two! Three!" in unison, just before a loud boom.[77] Nielson said that she had never spoken with either of the writers of the article,[78] and evidence suggests otherwise. Just before shooting himself, Klebold lit a Molotov cocktail on a nearby table, underneath which Ireland was lying, which caused the tabletop to momentarily catch fire. Underneath the scorched film of material was a piece of Harris's brain matter, suggesting Harris had shot himself by this point.[79][80]

Suggested rationales

There was controversy over whether Harris and Klebold should be memorialized. Some were opposed, saying that it glorified murderers, while others argued that Harris and Klebold were also victims. Atop a hill near Columbine High School, crosses were erected for Harris and Klebold along with those for the people they killed,[81] but the father of victim Daniel Rohrbough cut them down, saying that murderers should not be memorialized in the same place as victims.[82]

Overview

Harris and Klebold wrote some about how they would carry out the massacre, and less about why. Klebold penned a rough outline of plans to follow on April 20, and another slightly different one in a journal found in Harris's bedroom.[83] In one entry on his computer, Harris referenced the Oklahoma City bombing, and they mentioned their wish to outdo it by causing the most deaths in US history. They also mentioned how they would like to leave a lasting impression on the world with this kind of violence.[84] Much speculation occurred over the date chosen for their attack. The original intended date of the attack may have been April 19; Harris required more ammunition from Mark Manes, who did not deliver it until the evening of April 19.[85][86][87]

Harris and Klebold were both avid fans of KMFDM, an industrial band led by German multi-instrumentalist Sascha Konietzko. It was revealed that lyrics to KMFDM songs ("Son of a Gun", "Stray Bullet" and "Waste") were posted on Harris' website,[88] and that the date of the massacre, April 20, coincided with both the release date of the album Adios[89] and the birthday of Adolf Hitler.[90] Harris noted the coincidence of the album's title and April release date in his journal.[56] In response, KMFDM's Konietzko issued a statement that KMFDM was "against war, oppression, fascism and violence against others" and that "none of us condone any Nazi beliefs whatsoever".[91]

An April 22, 1999 article in The Washington Post described Harris and Klebold:

They hated jocks, admired Nazis and scorned normalcy. They fancied themselves devotees of the Gothic subculture, even though they thrilled to the violence denounced by much of that fantasy world. They were white supremacists, but loved music by anti-racist rock bands.[92]

The attack occurred on Hitler's birthday, which led to speculation in the media. Some people, such as Robyn Anderson, who knew the perpetrators, stated that the pair were not obsessed with Nazism nor did they worship or admire Hitler in any way. Anderson stated, in retrospect, that there were many things the pair did not tell friends. In his journal, Harris mentioned his admiration of what he imagined to be natural selection, and wrote that he would like to put everyone in a super Doom game and see to it that the weak die and the strong live.[56] On the day of the massacre, Harris wore a white T-shirt with the words "Natural selection" printed in black.[47]

Bullying

At the end of Harris' last journal entry, he wrote: "I hate you people for leaving me out of so many fun things. And no don't ... say, 'Well that's your fault,' because it isn't, you people had my phone number, and I asked and all, but no. No no no don't let the weird-looking Eric KID come along, ooh fucking nooo."[47]

Klebold said on the Basement Tapes, "You've been giving us shit for years. You're fucking gonna pay for all the shit! We don't give a shit. Because we're gonna die doing it."[93][94]

Accounts from various parents and school staffers describe bullying at the school as "rampant."[95] Nathan Vanderau, a friend of Klebold, and Alisa Owen, Harris's eighth-grade science partner, reported that Harris and Klebold were constantly picked on. Vanderau noted that a "cup of fecal matter" was thrown at them.[96] "People surrounded them in the commons and squirted ketchup packets all over them, laughing at them, calling them faggots," Brooks Brown says. "That happened while teachers watched. They couldn't fight back. They wore the ketchup all day and went home covered with it."[43] In his book, No Easy Answers: The Truth Behind Death at Columbine, Brown wrote that Harris was born with mild chest indent. This made him reluctant to take his shirt off in gym class, and other students would laugh at him.[44]

"A lot of the tension in the school came from the class above us," Chad Laughlin states. "There were people fearful of walking by a table where you knew you didn't belong, stuff like that. Certain groups certainly got preferential treatment across the board. I caught the tail end of one really horrible incident, and I know Dylan told his mother that it was the worst day of his life." That incident, according to Laughlin, involved seniors pelting Klebold with "ketchup-covered tampons" in the commons.[45] However, other commentators have disputed the theory that bullying was the motivating factor.[5]

Journals and investigation

Harris began keeping a journal in April 1998, a short time after the pair was convicted of breaking into a van, for which each received ten months of juvenile intervention counseling and community service in January 1998. They began to formulate plans then, as reflected in their journals.[86]

Harris wanted to join the United States Marine Corps, but his application was rejected shortly before the shootings because he was taking the drug fluvoxamine, an SSRI antidepressant, which he was required to take as part of court-ordered anger management therapy. Harris did not state in his application that he was taking any medications. According to the recruiting officer, Harris did not know about this rejection. Though some friends of Harris suggested that he had stopped taking the drug beforehand,[97] the autopsy reports showed low therapeutic or normal (not toxic or lethal) blood-levels of Luvox (fluvoxamine) in his system, which would be around 0.0031–0.0087 mg/ml,[98] at the time of death.[99] After the shootings, opponents of contemporary psychiatry like Peter Breggin[100] claimed that the psychiatric medications prescribed to Harris after his conviction may have exacerbated his aggressiveness.[101]

In his journal, Klebold wrote about his view that he and Harris were "god-like" and more highly evolved than every other human being, but his secret journal records self-loathing and suicidal intentions. Page after page was covered in hearts, as he was secretly in love with a Columbine student. Although both had difficulty controlling their anger, Klebold's anger had led to his being more prone to serious trouble than Harris. After their arrest, which both recorded as the most traumatic thing they had ever experienced, Klebold wrote a letter to Harris, saying how they would have so much fun getting revenge and killing police, and how his wrath from the January arrest would be "god-like". On the day of the massacre, Klebold wore a black T-shirt which had the word "WRATH" printed in red.[47] It was speculated that revenge for the arrest was a possible motive for the attack, and that the pair planned on having a massive gun battle with police during the shooting. Klebold wrote that life was no fun without a little death, and that he would like to spend the last moments of his life in nerve-wracking twists of murder and bloodshed. He concluded by saying that he would kill himself afterward in order to leave the world that he hated and go to a better place. Klebold was described as being "hotheaded, but depressive and suicidal."[6]

Some of the home-recorded videos, called "The Basement Tapes", have reportedly been destroyed by police. Harris and Klebold reportedly discussed their motives for the attacks in these videos and gave instructions in bomb making. Police cite the reason for withholding these tapes as an effort to prevent them from becoming "call-to-arms" and "how-to" videos that could inspire copycat killers.[102] Some people have argued that releasing the tapes would be helpful, in terms of allowing psychologists to study them, which in turn could possibly help identify characteristics of future killers.[103]

Media accounts

Initially,[48] the shooters were believed to be members of a clique that called themselves the "Trench Coat Mafia", a small group of Columbine's self-styled outcasts who wore heavy black trench coats. Early reports described the members as also wearing German slogans and swastikas on their clothes.[48] Additional media reports described the Trench Coat Mafia as a cult with ties to the Neo-Nazi movement which fueled a media stigma and bias against the Trench Coat Mafia. The Trench Coat Mafia was a group of friends who hung out together, wore black trench coats, and prided themselves on being different from the 'jocks' who had been bullying the members and who also coined the name Trench Coat Mafia.[104] The trench coat inadvertently became the members' uniform after a mother of one of the members bought it as a present.[48]

Investigation revealed that Harris and Klebold were only friends with one member of the group, Kristin Thiebault, and that most of the primary members of the Trench Coat Mafia had left the school by the time that Harris and Klebold committed the massacre. Most did not know the shooters, apart from their association with Thiebault, and none were considered suspects in the shootings or were charged with any involvement in the incident.[48]

Marilyn Manson was blamed by the media in the wake of the Columbine shooting, and responded to criticism in an interview with Michael Moore, in which he was asked, "If you were to talk directly to the kids at Columbine and the people in the community, what would you say to them if they were here right now?", to which he replied, "I wouldn't say a single word to them—I would listen to what they have to say, and that's what no one did," referring to people ignoring red flags that rose from Harris and Klebold prior to the shooting.[105]

Psychological analysis

Although early media reports attributed the shootings to a desire for revenge on the part of Harris and Klebold for bullying that they received, subsequent psychological analysis indicated Harris and Klebold harbored serious psychological problems. Harris and Klebold were never diagnosed with any mental disorders, which is overwhelmingly uncommon in mass shooters.[106] According to Supervisory Special Agent Dwayne Fuselier, the FBI's lead Columbine investigator and a clinical psychologist, Harris exhibited a pattern of grandiosity, contempt, and lack of empathy or remorse, distinctive traits of psychopaths that Harris concealed through deception. Fuselier adds that Harris engaged in mendacity not merely to protect himself, as Harris rationalized in his journal, but also for pleasure, as seen when Harris expressed his thoughts in his journal regarding how he and Klebold avoided prosecution for breaking into a van. Other leading psychiatrists concur that Harris was a psychopath.[6]

According to psychologist Peter Langman, Klebold displayed signs of schizotypal personality disorder – he struck many people as odd due to his shy nature, appeared to have had disturbed thought processes and constantly misused language in unusual ways as evidenced by his journal. He appeared to have been delusional, viewed himself as "god-like", and wrote that he was "made a human without the possibility of BEING human." He was also convinced that others hated him and felt like he was being conspired against, even though according to many reports, Klebold was loved by his family and friends.[107]

Lawsuits

In April 2001, the families of more than 30 victims were given shares in a $2,538,000 settlement by the families of the perpetrators, and the two men convicted of supplying the weapons used in the massacre. The Harrises and the Klebolds contributed $1,568,000 to the settlement from their own homeowners' policies, the Maneses contributed $720,000, and the Durans contributed $250,000. The Harrises and the Klebolds were ordered to guarantee an additional $32,000 be available against any future claims. The Maneses were ordered to hold $80,000 against future claims, and the Durans were ordered to hold $50,000.[108]

One family had filed a $250-million lawsuit against the Harrises and Klebolds in 1999 and did not accept the 2001 settlement terms. A judge ordered the family to accept a $366,000 settlement in June 2003.[109][110] In August 2003, the families of five other victims received undisclosed settlements from the Harrises and Klebolds.[109]

Reaction of Sue Klebold

Sue Klebold, mother of Klebold, initially was in denial about Klebold's involvement in the massacre, believing he was tricked by Harris into doing it, among other things. Six months later, she saw the Basement Tapes made by Harris and Klebold, and acknowledged that Klebold was equally responsible for the killings.[111] She spoke about the Columbine High School massacre publicly for the first time in an essay that appeared in the October 2009 issue of O: The Oprah Magazine. In the piece, Klebold wrote: "For the rest of my life, I will be haunted by the horror and anguish Dylan caused", and "Dylan changed everything I believed about myself, about God, about family, and about love." Stating that she had no clue of her son's intentions, she said, "Once I saw his journals, it was clear to me that Dylan entered the school with the intention of dying there."[112] In Andrew Solomon's 2012 book Far from the Tree, she acknowledged that on the day of the massacre, when she discovered that Klebold was one of the shooters, she prayed he would kill himself. "I had a sudden vision of what he might be doing. And so while every other mother in Littleton was praying that her child was safe, I had to pray that mine would die before he hurt anyone else."[113]

In February 2016, Klebold published a memoir, titled A Mother's Reckoning, about her experiences before and after the massacre.[114][115] It was co-written by Laura Tucker and included an introduction by National Book Award winner Andrew Solomon. It received very favorable reviews, including from the New York Times Book Review.[116] It peaked at No. 2 on The New York Times Best Seller list.[117]

On February 2, 2017, Klebold posted a TED Talk titled, "My son was a Columbine shooter. This is my story."[118] As of March 2021, the video has over 11.5 million views. The site listed Klebold's occupation as "activist", and stated: "Sue Klebold has become a passionate agent working to advance mental health awareness and intervention."[119]

Legacy

ITV describes the legacy of Harris and Klebold as deadly, as they have inspired several instances of mass killings in the United States. Napa Valley Register have called the pair "cultural icons".[120] Author of Columbine, Dave Cullen, called Harris and Klebold the fathers of the movement for disenfranchised youth.[121] Harris and Klebold have also, as CNN referred to, left their inevitable mark on pop culture.[122]

Copycats

The Columbine shooting influenced several subsequent school shootings, with many praising Harris and Klebold, referring to them as martyrs, heroes or Gods.[123][124] In some cases, it has led to the closure of entire school districts.[125] According to psychiatrist E. Fuller Torrey of the Treatment Advocacy Center, a legacy of the Columbine shootings is its "allure to disaffected youth."[126]

Ralph Larkin examined twelve major school shootings in the US in the following eight years and found that in eight of those, "the shooters made explicit reference to Harris and Klebold."[127] Larkin wrote that the Columbine massacre established a "script" for shootings. "Numerous post-Columbine rampage shooters referred directly to Columbine as their inspiration; others attempted to supersede the Columbine shootings in body count."[128]

A 2015 investigation by CNN identified "more than 40 people...charged with Columbine-style plots." A 2014 investigation by ABC News identified "at least 17 attacks and another 36 alleged plots or serious threats against schools since the assault on Columbine High School that can be tied to the 1999 massacre." Ties identified by ABC News included online research by the perpetrators into the Columbine shooting, clipping news coverage and images of Columbine, explicit statements of admiration of Harris and Klebold, such as writings in journals and on social media, in video posts,[d] and in police interviews, timing planned to an anniversary of Columbine, plans to exceed the Columbine victim counts, and other ties.[130] 60 mass shootings have been carried out, where the perpetrators had made at least a single reference to Harris and Klebold.[131]

In 2015, journalist Malcolm Gladwell writing in The New Yorker magazine proposed a threshold model of school shootings in which Harris and Klebold were the triggering actors in "a slow-motion, ever-evolving riot, in which each new participant's action makes sense in reaction to and in combination with those who came before."[127][132]

Fandom

Harris and Klebold have also spawned a fandom who call themselves "Columbiners," mostly apparent on blogging site Tumblr. While some just have a scholarly interest in the pair or the event, the vast majority of these individuals, mostly young women, express a sympathetic, or sometimes even sexual interest, in Harris and Klebold.[133] There has been homoerotic art drawn of the two, fan fiction created on the pair's future together had they not gone through with the shooting and costumes created on the outfits Harris and Klebold sported the day of the shootings.[134]

"I relate to their feelings of hopelessness, being angry and not being able to change it, and wanting to be accepted and appreciated," an 18 year old Tumblr user wrote on Harris and Klebold. "No one noticed they were struggling, and no one took their suffering seriously," added another user. News site, "All That's Interesting" said on the fandom, "Many of these Columbiners have no positive feelings about the massacre, but are instead focused on the troubled inner lives of its perpetrators because they see themselves in them."[134] The fandom has received much criticism, by allegedly inspiring shooting plots by heroizing Harris and Klebold, such as the Halifax mass shooting plot.[135]

In popular culture

The 2002 Michael Moore documentary film Bowling for Columbine focuses heavily on a perceived American obsession with handguns, its grip on Jefferson County, Colorado, and its role in the shooting.

The 2003 Gus Van Sant film Elephant depicts a fictional school shooting, though some of its details were based on the Columbine massacre, such as one scene in which one of the young killers walks into the evacuated school cafeteria and pauses to take a sip from a drink left behind, as Harris did during the shooting.[96][136] In the film, the killers are called "Alex and Eric" after the actors who portray them, Alex Frost and Eric Deulen.

In the 2003 Ben Coccio film Zero Day, which was inspired by the Columbine shooting, the two shooters are played by Andre Kriegman and Cal Gabriel and called "Andre and Calvin" after their actors.[137]

In 2004, the shooting was dramatized in the documentary Zero Hour, in which Harris and Klebold are played by Ben Johnson and Josh Young, respectively.[138]

In 2005, game designer Danny Ledonne created a role-playing video game where the player assumes the role of Harris and Klebold during the massacre, entitled Super Columbine Massacre RPG!.[139] The game received substantial media backlash for allegedly glorifying the pair's actions. The father of one victim remarked to the press that the game "disgusts me. You trivialize the actions of two murderers and the lives of the innocent."[140]

The 2016 biographical film I'm Not Ashamed, based on the journals of Rachel Scott, includes glimpses of Harris' and Klebold's lives and of interactions between them and other students at Columbine High School. Harris is played by David Errigo Jr. and Klebold is played by Cory Chapman.[141]

See also

Notes

- ^ Neither Harris nor Klebold used their knives during the shooting.

- ^ Harris and Klebold directly wounded 21 people by gunfire; three others received injuries related to the attack.

- ^ Many early reports said the Columbine massacre was the worst school-related massacre in U.S. history.[2] However, the 1927 Bath School disaster (a bombing) left 44 dead. The 1966 University of Texas tower shooting was the deadliest school shooting at the time.

- ^ In 2012, sociologist Nathalie E. Paton of the National Center for Scientific Research in Paris analyzed the videos created by post-Columbine school shooting perpetrators. A recurring set of motifs was found, including explicit statements of admiration and identification with previous perpetrators. Paton said the videos serve the perpetrators by distinguishing themselves from their classmates and associating themselves with the previous perpetrators.[127][129]

References

- ^ "2010 Census – Census Block Map: Columbine CDP, CO Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine" U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on April 25, 2015. The school's location is on Pierce Street, which runs north-south through Columbine, roughly one mile west of the Littleton city limit.

- ^ "Columbine – Tragedy and Recovery". extras.denverpost.com. The Denver Post. Archived from the original on May 2, 2021. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ Garrison, Robert (April 12, 2019). "Columbine High School shooting focused on "Trench Coat Mafia"". The Lamar Ledger. Archived from the original on September 21, 2021. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- ^ Margaritoff, Marco (March 8, 2019). "The Full Story Behind Columbine High School Shooters Eric Harris And Dylan Klebold". allthatisinteresting.com. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brockell, Gillian (April 20, 2019). "Bullies and black trench coats: The Columbine shooting's most dangerous myths". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 28, 2019. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Cullen, Dave (April 20, 2004). "THE DEPRESSIVE AND THE PSYCHOPATH: At last we know why the Columbine killers did it". Slate. Archived from the original on October 4, 2018. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- ^ Sancier, Greg (April 18, 2014). "Looking into the minds of Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold". police1.com. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- ^ Joyce, Kathleen (November 2, 2018). "2 Kentucky high school girls suspended after dressing up as Columbine shooters for Halloween". Fox News. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Suspects Text". CNN. Archived from the original on July 26, 2012. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- ^ "LETHAL GEEKS WERE MADE FOR EACH OTHER". Archived from the original on June 4, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ Kass, Jeff (February 18, 2014). Columbine: A True Crime Story. Conundrum Press. ISBN 9781938633270. Archived from the original on September 21, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Li, David K. (April 22, 1999). "Lethal Geeks Were Made For Each Other". New York Post. Archived from the original on June 4, 2020. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- ^ Briggs, Bill; Blevins, Jason (May 2, 1999). "A Boy With Many Sides". Denver Post. Archived from the original on October 27, 2011. Retrieved September 8, 2011.

- ^ "Columbine killer envisioned crashing plane in NYC". CNN. December 6, 2001. Archived from the original on October 6, 2011. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ^ Santiago, Ellyn (April 17, 2019). "Eric Harris' Parents & Brother, Wayne, Kathy & Kevin Harris: 5 Fast Facts You Need to Know". Heavy.com. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ^ Belluck, Pam; Wilgoren, Jodi (June 29, 1999). "SHATTERED LIVES – A special report.; Caring Parents, No Answers, In Columbine Killers' Pasts". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ "SWAT_MOVE_TEXT". CNN. Archived from the original on January 24, 2020. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- ^ "Portrait of two teens reveals a lot of gray". The Christian Science Monitor. May 3, 1999. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ "Eric Harris". www.biography.com. Archived from the original on April 14, 2020. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- ^ "The Denver Post Online – Columbine – Tragedy and Recovery". extras.denverpost.com. Archived from the original on February 25, 2018. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 23, 2019. Retrieved August 22, 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Dukakis, Andrea. "'I'll Never Know If I Could Have Prevented It,' Says Mother Of Columbine Shooter". Colorado Public Radio. Archived from the original on August 5, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ "Life and death of a follower". Archived from the original on June 16, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Leppek, Chris (April 30, 1999). "Dylan Klebold led life of religious contradictions". Archived from the original on March 29, 2007. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- ^ A Mother's Reckoning: Living in the Aftermath of the Columbine Tragedy p. 84

- ^ Culver, Virginia (April 28, 1999). "Klebolds 'loneliest people on the planet'" Archived September 21, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. The Denver Post.

- ^ "Dylan Klebold – Columbine School Shooting, Parents & Journal". www.biography.com. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 23, 2019. Retrieved August 22, 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 8, 2019. Retrieved September 24, 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Portrait of two teens reveals a lot of gray". Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ "The Columbine Shooters". Archived from the original on November 11, 2018. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ "A boy with many sides". Archived from the original on June 7, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Psychologists say Harris, Klebold became deadly mix". Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 15, 2015. Retrieved October 6, 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Kohn, David (April 17, 1999). "Columbine: Were There Warning Signs?". CBS News. Archived from the original on July 6, 2020. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 19, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Prendergast, Alan (April 17, 2009). "Forgiving my Columbine High School friend, Dylan Klebold". Westword. Archived from the original on June 21, 2019. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

- ^ Hari, Johann (January 15, 2004). "The cult of Eric and Dylan". The Independent. Archived from the original on May 30, 2019. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- ^ Prendergast, Alan (April 17, 2009). "Forgiving my Columbine High School friend, Dylan Klebold". Westword. Archived from the original on June 21, 2019. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- ^ XxSlenderMotoxX (November 9, 2012). "Zero Hour – Massacre at Columbine High". Archived from the original on June 13, 2019. Retrieved June 30, 2019 – via YouTube.

- ^ Vodka'sHypnosis (April 24, 2016). "Sue Klebold's Interview: After Words With Sue Klebold – BOOK TV". Archived from the original on December 8, 2019. Retrieved June 30, 2019 – via YouTube.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Prendergast, Alan (July 13, 2000). "The Missing Motive". Denver Westword News. Archived from the original on July 28, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brown, Brooks; Merritt, Rob (2002). No Easy Answers: The Truth Behind Death at Columbine. New York City: Lantern Books. ISBN 978-1-59056-031-0. Archived from the original on May 31, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Prendergast, Alan (April 17, 2009). "Forgiving my Columbine High School friend, Dylan Klebold". Denver Westword Post. Archived from the original on April 20, 2009. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ^ Brooks, David (April 24, 2004). "The Columbine Killers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 4, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Toppo, Greg (April 14, 2009). "10 years later, the real story behind Columbine". USA Today. Archived from the original on April 15, 2009. Retrieved April 14, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Wilgoren, Jodi (April 25, 1999). "Terror in Littleton: the Group; Society of Outcasts Began With a $99 Black Coat". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 26, 2017.

- ^ "Who are the Trenchcoat Mafia?". BBC News. April 21, 1999. Archived from the original on September 2, 2013.

- ^ Kass, Jeff (2009). Columbine: A True Crime Story. Denver, Colorado: Ghost Road Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-9816525-6-6. Archived from the original on January 5, 2014. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- ^ Bartels, Linda; Crowder, Carla (August 22, 1999). "Fatal Friendship". Denver Rocky Mountain News. Archived from the original on October 25, 2008. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ "Harris hinted at violence to come". CNN. April 22, 1999. Archived from the original on August 26, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ Bachman, Ronet D.; Schutt, Russell K.; Plass, Peggy S. (December 19, 2015). Fundamentals of Research in Criminology and Criminal Justice: With Selected Readings. ISBN 9781506326696. Archived from the original on November 7, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 14, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Cullen, Dave. "Eric's big lie". Columbine Online. Archived from the original on January 19, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Shepard, Cyn. "Columbine shooter Eric Harris' Journals and Writing". Acolumbinesite.com. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved October 31, 2016.

- ^ Klebold, Dylan Bennet; Harris, Eric David (December 1998). "Hitmen for Hire". Columbine, Colorado. Archived from the original on September 25, 2018. Retrieved October 4, 2018.

- ^ Shepard, Cyn. "Eric's writing: Creative writing story". A Columbine Site. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

- ^ Shepard, Cyn. "Gunfire in the halls". A Columbine Site. Archived from the original on September 17, 2010. Retrieved August 24, 2008.

- ^ "Gunman's prom date airs story". Archived from the original on June 10, 2019. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ "How they were equipped that day". CNN. Archived from the original on December 2, 2009. Retrieved November 25, 2009.

- ^ Pankratz, Howard; Simpson, Kevin (November 13, 1999). "Judge gives Manes 6 years". The Denver Post. Archived from the original on October 20, 2014. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ^ "The Bombs: The Columbine Guide-Eric Harris & Dylan Klebold Sue". columbine-guide. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Bartels, Lynn (April 12, 2002). "At 'perfect' school, student sat next to bomb". Rocky Mountain News. Archived from the original on April 20, 2008. Retrieved August 24, 2008.

- ^ Rimer, Sara (April 24, 1999). "TERROR IN LITTLETON: THE SENIORS; In Horrific Circumstance, Sense of Lost Pomp". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 8, 2019. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- ^ Brown, Brooks (April 18, 2007). "Columbine Survivor With Words for Virginia Students". NPR. Archived from the original on December 8, 2008. Retrieved August 24, 2008.

- ^ "Friend of Columbine Killers Still Seeking Answers". Monroe, CT Patch. November 27, 2012. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ Donnelly, Keryn (January 20, 2018). "The chance mistake that saved hundreds of lives on the day of the Columbine shooting". Mamamia.com.au. Archived from the original on January 1, 2020. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ^ Morris, Sam (February 15, 2018). "Mass shootings: what are the deadliest attacks in the US?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 15, 2018. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- ^ Earl, Jennifer (February 14, 2018). "Florida school shooting among 10 deadliest in modern US history". Fox News. Archived from the original on February 15, 2018. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ "Daniel Lee Rohrbough". A Columbine Site. Archived from the original on December 9, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- ^ "13 Victims killed at Columbine High School". www.acolumbinesite.com. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ "Injured and Survivors of the Columbine High School shooting". www.acolumbinesite.com. Archived from the original on February 16, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ "Findings of Library Events". Jefferson County Sheriff's Office (Colorado). CNN International. Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Berg Olsen, Martine (April 20, 2019). "Remembering the 13 victims of Columbine High School massacre 20 years on". Metro.co.uk. Archived from the original on March 21, 2020. Retrieved March 21, 2020.

- ^ "Injured and Survivors of the Columbine High School shooting". www.acolumbinesite.com. Archived from the original on April 25, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ Bartels, Lynn; Carla Crowder (1999). "Fatal Friendship". The Rocky Mountain News. Archived from the original on February 21, 2001. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ Progress Report, Case # 99-16215 Archived September 4, 2015, at the Wayback Machine pp. 98–99

- ^ Columbine Report documents, p. JC-001-008937

- ^ Krabbé, Tim (2012). Wij Zijn Maar Wij Zijn Niet Geschift. Prometheus. p. 30. ISBN 9789044620542.

- ^ Fong, Tillie (April 28, 1999). "Crosses for Harris, Klebold join 13 others". Rocky Mountain News. Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved August 24, 2008.

- ^ Zewe, Charles (May 1, 1999). "Authorities say Columbine shooters acted alone". CNN. Archived from the original on February 11, 2007. Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- ^ "Columbine Documents" (PDF). Rocky Mountain News. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 10, 2008. Retrieved August 24, 2008.

- ^ "Columbine killers' diaries offer chilling insight". msnbc.com. July 7, 2006. Archived from the original on August 5, 2018. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- ^ Hinton, Sam (2012). "Troubled Children: Dealing with Anger and Depression". Psychology of Children: Coping with the Dangerous Threats. Hammond. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-275-98207-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ryckman, Lisa (May 16, 2000). "Demonic plan was months in making". Rocky Mountain News. Archived from the original on January 25, 2009.

- ^ "The Denver Post Online – Columbine – Tragedy and Recovery". Archived from the original on June 7, 2019. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- ^ Wilson, Scott (2008). "Columbine". Great Satan's Rage. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-0-7190-7463-9. Archived from the original on September 21, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ "KMFDM And Rammstein Speak Out About Columbine". MTV Networks. April 23, 1999. Archived from the original on February 9, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ "Music Linked To Killings?". Philadelphia Daily News. Knight Ridder. April 22, 1999. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ Boehlert, Eric (April 23, 1999). "An Old Debate Emerges in Wake of School Shooting". Rolling Stone. New York City: Wenner Media. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ Duggan, Paul; Shear, Michael D.; Fisher, Marc (April 22, 1999). "Shooter Pair Mixed Fantasy, Reality". The Washington Post. p. A1. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ "Massacre at Columbine High". Zero Hour. Season 1. Episode 3. 2004. History. Archived from the original on January 8, 2015. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- ^ "Transcript of the Columbine "Basement Tapes"" (PDF). Schoolshooters.info. July 29, 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 15, 2015. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ^ Pankratz, Howard (October 3, 2000). "Columbine bullying no myth, panel told". Denver Post. Archived from the original on June 7, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Investigative Reports: Columbine: Understanding Why on YouTube. A&E. 2002

- ^ Gibbs, Nancy; Timothy Roche (December 20, 1999). "The Columbine Tapes". TIME. Archived from the original on February 8, 2009. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ^ Winek, Charles L.; et al. (2001). "Drug and chemical blood-level data 2001" (PDF). Forensic Science International. 122 (2–3): 107–123. doi:10.1016/s0379-0738(01)00483-2. PMID 11672964. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 6, 2013. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- ^ Shepard, Cyn. "Eric David Harris". A Columbine Site. Archived from the original on October 12, 2011. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ^ Breggin, Peter R. (April 30, 1999). "Was School Shooter Eric Harris Taking Luvox?". Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2009.

- ^ Larkin, Ralph W. (2007). Comprehending Columbine. Temple University Press. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-59213-491-5.

- ^ Duwe, Grant (2007). Mass and Serial Murder in America. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 41. ISBN 978-3-31944280-8.

- ^ Prendergast, Alan (February 2, 2015). "Columbine Killers' Basement Tapes Destroyed". Westword. Archived from the original on July 23, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ Brown, Brooks; Merritt, Rob (2002). No easy answers: The truth behind death at Columbine. Lantern Books. pp. 68–70. ISBN 1590560310. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- ^ Michael Moore interviewing Marilyn Manson (October 11, 2002). Bowling for Columbine (Documentary). Los Angeles, California: MGM.

- ^ "Looking into the minds of Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold". Police1. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ Langman, Peter (2016) [2010], Rampage School Shooters: A Typology (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on July 12, 2019, retrieved July 12, 2019

- ^ Janofsky, Michael (April 20, 2001). "$2.53 Million Deal Ends Some Columbine Lawsuits". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 24, 2014. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Columbine High School Shootings Fast Facts". CNN. September 19, 2013. Archived from the original on October 13, 2014. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ^ "$250 million Columbine lawsuit filed". CNN. May 27, 1999. Archived from the original on January 13, 2014. Retrieved January 13, 2014.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 21, 2019. Retrieved July 27, 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Klebold, Susan (November 2009). "I Will Never Know Why". O, The Oprah Magazine. Archived from the original on February 18, 2016. Retrieved October 21, 2009.

- ^ "Columbine Shooter Dylan Klebold's Parents Speak Out". Archived from the original on November 29, 2012. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- ^ "Columbine shooter Dylan Klebold's mother to hold first TV interview". ABC News. July 23, 2015. Archived from the original on January 6, 2016. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- ^ Klebold, Sue (2016). A Mother's Reckoning: Living in the Aftermath of Tragedy. Amzon.com. ISBN 978-1101902752.

- ^ "Inside The New York Times Book Review Podcast: 'A Mother's Reckoning'". The New York Times. February 26, 2016. Archived from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- ^ "#2 New York Times bestseller: "Mesmerizing, heart-stopping. I beseech"". lauratuckerbooks.com. Archived from the original on October 29, 2016. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- ^ Klebold, Sue. "My son was a Columbine shooter. This is my story". Archived from the original on February 4, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- ^ Klebold, Sue. "A Note from Sue Klebold". amothersreckoning.com. A Mother's Reckoning. Archived from the original on August 14, 2020. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on June 29, 2019. Retrieved June 29, 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 7, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Columbine left its indelible mark on pop culture - CNN.com". www.cnn.com. Archived from the original on October 30, 2019. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- ^ Gibbs, Nancy; Roche, Timothy (December 12, 1999). "The Columbine Tapes" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 7, 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2019 – via content.time.com.

- ^ "Shooter: 'You have blood on your hands'". CNN. April 18, 2007. Archived from the original on October 18, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ^ "Intermittent Explosive Disorder". mayhem.net. Archived from the original on December 20, 2010. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

- ^ Drash, Wayne (November 3, 2015). "The massacre that didn't happen". CNN. Archived from the original on April 2, 2017. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gladwell, Malcolm (October 19, 2015). "Thresholds of Violence, How school shootings catch on". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on March 27, 2017. Retrieved April 1, 2017.

- ^ Larkin, Ralph W. (2009). "The Columbine legacy: Rampage shootings as political acts". American Behavioral Scientist. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publishing. 52 (9): 1309–1326. doi:10.1177/0002764209332548. S2CID 144049077. Archived from the original on April 3, 2017. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- ^ Paton, Nathalie E. (2012). "Media participation of school shooters and their fans: Navigating between self-distinction and imitation to achieve individuation" (PDF). In Muschert, Glenn W.; Sumiala, Johanna (eds.). School shootings: Mediatized violence in a global age. 7. Emerald Group Publishing. pp. 203–229. ISBN 9781780529196. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 18, 2017. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- ^ Thomas, Pierre; Levine, Mike; Cloherty, Jack; Date, Jack (October 7, 2014). "Columbine Shootings' Grim Legacy: More Than 50 School Attacks, Plots". ABC News. Archived from the original on April 17, 2017. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Weller, Chris (October 13, 2015). "Malcolm Gladwell says the school shooting epidemic is like a slow-moving riot". Business Insider. Archived from the original on April 18, 2017. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- ^ "Inside the World of Columbine-Obsessed Tumblr Bloggers". www.vice.com. Archived from the original on June 23, 2019. Retrieved June 23, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Enter The World Of Online Fans Who Are Infatuated With The Columbine Shooters". All That's Interesting. April 19, 2019. Archived from the original on June 23, 2019. Retrieved June 23, 2019.

- ^ Monroe, Rachel (August 20, 2019). "The cult of Columbine: how an obsession with school shooters led to a murder plot". Archived from the original on March 21, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020 – via www.theguardian.com.

- ^ Doland, Angela (May 21, 2003). "2003: Shades of Columbine". CBS News. Archived from the original on November 20, 2010. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ Roeder, Amy (September 1, 2002). "Zero Score". New England Film. Archived from the original on February 5, 2010.

- ^ "Massacre at Columbine High". Archived from the original on March 3, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020 – via www.imdb.com.

- ^ Vaughan, Kevin; Brian Crecente (May 16, 2006). "Video game reopens Columbine wounds; Parents of victims are horrified; creator says it's for 'real dialogue'". Rocky Mountain News. Archived from the original on June 14, 2006. Retrieved January 9, 2015.

- ^ Staff (May 20, 2006). "Columbine game disgusts families". The Evening Standard. p. 14.

- ^ "'I'm Not Ashamed' is better than it looks (but also bad and offensive)". Metro US. Archived from the original on July 3, 2020. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

Further reading

- Brown, Brooks; Rob Merritt (2002). No Easy Answers: The Truth Behind Death at Columbine. Lantern Books. ISBN 1-59056-031-0.

- Cullen, Dave (2009). Columbine. TwelveBooks. ISBN 978-0-446-54693-5.

- Daggett, Chelsea (November 2015). "Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold: Antiheroes for outcasts" (PDF). . 12 (2). ISSN 1749-8716.

- Kass, Jeff (2009). Columbine: A True Crime Story. Ghost Road Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-9816525-6-6.

- Larkin, Ralph W. (2007). Comprehending Columbine. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-59213-491-5.

- Rico, Andrew Ryan (September 1, 2015). "Fans of Columbine shooters Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold". Transformative Works and Cultures. 20. doi:10.3983/twc.2015.0671.

External links

- Crimelibrary feature

- Eric Harris at Find a Grave

- Dylan Klebold at Find a Grave

- Eric Harris at IMDb

- Dylan Klebold at IMDb

- 1981 births

- 1999 suicides

- 20th-century American criminals

- American arsonists

- American male criminals

- American mass murderers

- American murderers of children

- American victims of school bullying

- American white supremacists

- Bombers (people)

- Bullying and suicide

- Columbine High School alumni

- Columbine High School massacre

- Criminal duos

- Criminals from Colorado

- Youth suicides

- Joint suicides

- Murder–suicides in Colorado

- People from Littleton, Colorado

- People from the Denver metropolitan area

- Suicides by firearm in Colorado