Eshnunna

Eshnunna Eshnunna | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 3000 BC–c. 1700 BC | |||||||||

Eshnunna  Eshnunna Eshnunna (Iraq) | |||||||||

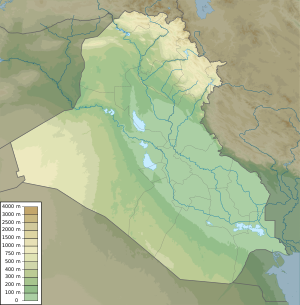

| Capital | Eshnunna 33°29′3″N 44°43′42″E / 33.48417°N 44.72833°ECoordinates: 33°29′3″N 44°43′42″E / 33.48417°N 44.72833°E | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

• c. 2000 BC | (first) | ||||||||

• c. 1700 BC | (last) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | ||||||||

• Established | c. 3000 BC | ||||||||

• Disestablished | c. 1700 BC | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Iraq | ||||||||

Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar in Diyala Governorate, Iraq) was an ancient Sumerian (and later Akkadian) city and city-state in central Mesopotamia. Although situated in the Diyala Valley north-west of Sumer proper, the city nonetheless belonged securely within the Sumerian cultural milieu.

The tutelary deity of the city was Tishpak (Tišpak).

History[]

Occupied since the Jemdet Nasr period around 3000 BCE,[clarification needed] Eshnunna was a major city during the Early Dynastic period of Mesopotamia, beginning with the rise of the Akkadian Empire. The first king of the city was a governor under the Third dynasty of Ur named Ituria. Ituria built a palace and a temple dedicated to Shu-Sin.[1][2] The next king was Shu-ija, who declared independence from Ur in 2026 BCE. Shu-ija's successors used the title of governor, not king, as the title of king of the city belonged to Tishpak, the city's god.

In 2010 BCE, King Nurahum I of Eshnunna and the city of Isin won a battle against the city of Subartu.[1] The following kings, named Kirikiri and Bilalamaboth, had Elamite names, suggesting that Eshnunna retained good relationships with the Elamites, although it seems unlikely they were conquered by them.[1] The city was later sacked, possibly by Anum-Muttabbil of Der.[1] As such, little is known about its next kings.[1] By 1870 BCE, Eshnunna was revived.[1] This could have occurred due to the decline of the cities of Isin and Larsa.[1]

During the years in between 1862 and 1818 BCE, King Ipiqadad II conquered the cities of Nerebtum and Dur-Rimush.[1] From 1830-1815 BCE, king Naramsin expanded Eshnunna's territory to Babylon, Ekallatum, and Ashur.[1] In 1780 BCE the kingdom of Assyria, led by Shamshi-Adad I, attacked Eshnunna and reconquered the cities of Nerebtum and Shaduppum. These cities were later conquered by Eshnunna in 1776 BCE following Shamshi-Adad's death.[1][3] In 1764 BCE, King Silli-Sin formed a coalition with Mari to attack Babylon, but this failed.[1] Following Eshnunna's capture by Babylon in 1762 BCE,[4] the city suffered a great flood. During 1741-1736 BCE Eshnunna's governor Anni sided with a king of Larsa in a rebellion against Babylon. Anni was captured and executed by the Babylonians, and the city itself was destroyed by Hammurabi.

Because of its promise of control over lucrative trade routes, Eshnunna could function somewhat as a gateway between Mesopotamian and Elamite culture. The trade routes gave it access to many exotic, sought-after goods such as horses from the north, copper, tin, and other metals and precious stones. In a grave in Eshnunna, a pendant made of copal from Zanzibar was found.[5] A small number of seals and beads from the Indus Valley Civilization were also found.[6]

Archaeology[]

The remains of the ancient city are now preserved in the tell, or archaeological settlement mound, of Tell Asmar, some 38 km northeast of Baghdad and 15 km in a straight line east of Baqubah. It was first located by Henri Pognon in 1892 but he neglected to report the location before he died in 1921. It was refound and excavated in six seasons between 1930 and 1936 by an Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago team led by Henri Frankfort with Thorkild Jacobsen and Seton Lloyd.[7][8][9][10][11][12] The expedition's field secretary was Mary Chubb.[13]

Despite the length of time since the excavations at Tell Asmar, the work of examining and publishing the remaining finds from that dig continues to this day. [14] These finds include roughly 1,500 cuneiform tablets.[15]

In the late 1990s, Iraqi archaeologists worked at Tell Asmar. The results from that excavation have not yet been published.[16]

Laws of Eshnunna[]

The Laws of Eshnunna consist of two tablets, found at Shaduppum (Tell Harmal) and a fragment found at Tell Haddad, the ancient Mê-Turan.[17] They were written sometime around the reign of king Dadusha of Eshnunna and appear to not be official copies. When the actual laws were composed is unknown. They are similar to the Code of Hammurabi.[18]

Square Temple of Abu[]

During the Early Dynastic period, the Abu Temple at Tell Asmar (Eshnunna) went through a number of phases. This included the Early Dynastic Archaic Shrine, Square Temple, and Single-Shrine phases of construction. They, along with sculpture found there, helped form the basis for the three part archaeological separation of the Early Dynastic period into ED I, ED II, and ED III for the ancient Near East.[19] A cache of 12 gypsum temple sculptures, in a geometric style, were found in the Square Temple; these are known as the Tell Asmar Hoard. They are some of the best known examples of ancient Near East sculpture. The group, now split up, show gods, priests and donor worshippers at different sizes, but all in the same highly simplified style. All have greatly enlarged inlaid eyes, but the tallest figure, the main cult image depicting the local god, has enormous eyes that give it a "fierce power".[20][21][22]

Rulers[]

| Ruler | Proposed reign | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ~2247 BC[23] | Governor under Shulgi of the Third Dynasty of Ur | |

| Governor under Shulgi of the Third Dynasty of Ur | ||

| Governor under Shu-Sin of the Third Dynasty of Ur | ||

| Governor under Ibbi-Sin of the Third Dynasty of Ur | ||

| Governor under Ibbi-Sin of the Third Dynasty of Ur, Contemporary of Ishbi-Erra of Isin | ||

| Contemporary of of Elam | ||

| Contemporary of of Tutub and Sumu-abum of Babylon | ||

| ~1700 BC | Reigned at least 36 years | |

| Naram-Sin | Son of Ipiq-Adad II, Contemporary of Shamshi-Adad I | |

| Approximate position | ||

| Dadusha | Son of Ipiq-Adad II, Contemporary of Shamshi-Adad I | |

| Ibal-pi-El II | Contemporary of Zimri-Lim of Mari, Killed by Siwe-palar-huppak of Elam who captured Eshnunna | |

See also[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eshnunna. |

- List of cities of the ancient Near East

- Khafajah

- Tell Ishchali

- Short chronology

- Mari (ally)

- Andarig (ally)

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Kingdoms of Mesopotamia - Eshnunna". www.historyfiles.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- ^ Frankfort, Henri (1948). Kingship and the Gods: A Study of Ancient Near Eastern Religion as the Integration of Society and Nature. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-26011-2.

- ^ Kupper, Jean Robert. Northern Mesopotamia and Syria. CUP Archive.

- ^ Tetlow, Elisabeth Meier (2004-12-28). Women, Crime and Punishment in Ancient Law and Society: Volume 1: The Ancient Near East. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-8264-1628-5.

- ^ Carol Meyer et al., "From Zanzibar to Zagros: A Copal Pendant from Eshnunna," Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 289–298, 1991

- ^ Henri Frankfort, "The Indus civilization and the Near East." Annual Bibliography of Indian Archaeology for 1932, Leyden, VI, pp. 1–12, 1934

- ^ [1] Henri Frankfort, Thorkild Jacobsen, and Conrad Preusser, Tell Asmar and Khafaje: The First Season's Work in Eshnunna 1930/31, Oriental Institute Communication 13, 1932

- ^ [2] Henri Frankfort, Tell Asmar, Khafaje and Khorsabad: Second Preliminary Report of the Iraq Expedition, Oriental Institute Communication 16, 1933

- ^ [3] Henri Frankfort, Iraq Excavations of the Oriental Institute 1932/33: Third Preliminary Report of the Iraq Expedition, Oriental Institute Communication 17, 1934

- ^ [4] Henri Frankfort with a chapter by Thorkild Jacobsen, Oriental Institute Discoveries in Iraq, 1933/34: Fourth Preliminary Report of the Iraq Expedition, Oriental Institute Communication 19, 1935

- ^ [5] Henri Frankfort, Progress of the Work of the Oriental Institute in Iraq, 1934/35: Fifth Preliminary Report of the Iraq Expedition, Oriental Institute Communication 20, 1936

- ^ [6] Henri Frankfort, Seton Lloyd, and Thorkild Jacobsen with a chapter by Günter Martiny, The Gimilsin Temple and the Palace of the Rulers at Tell Asmar, Oriental Institute Publication 43, 1940

- ^ Chubb, Mary (7 November 1961). "Rebuilding The Tower Of Babel". The Times (55232).

- ^ [7] Lise A. Truex, 3 Households and Institutions: A Late 3rd Millennium BCE Neighborhood at Tell Asmar, Iraq (Ancient Eshnunna), Special Issue: Excavating Neighborhoods: A Cross‐Cultural Exploration, American Anthropological Association, vol. 30, iss. 1, July 2019

- ^ [8] Clay Sealings And Tablets From Tell Asmar, The Oriental Institute News and Notes, no. 159, pp. 1-5, Oriental Institute of Chicago, Fall 1998

- ^ TAARII efforts to rescue Iraqi Archaeological publications

- ^ In Al-Rawi, Sumer 38 (1982, pp 117-20); the excavations are surveyed in Iraq 43 (1981:177ff); Na'il Hanoon, in Sumer 40 pp 70ffIraq 47 (1985)

- ^ The Laws of Eshnunna, Reuven Yaron, BRILL, 1988, ISBN 90-04-08534-3

- ^ "The Square Temple at Tell Asmar and the Construction of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia ca. 2900-2350 B.C.E,", Jean M Evans, American Journal of Archaeology, Boston, Oct 2007, Vol. 111, Iss. 4; pg. 599

- ^ Frankfort, Henri, The Art and Architecture of the Ancient Orient, Pelican History of Art, 4th ed 1970, pp. 46-49, Penguin (now Yale History of Art), ISBN 0140561072; the group are now divided between the Metropolitan Museum, New York, Oriental Institute, Chicago, and the National Museum of Iraq (with the god).

- ^ [9] Henri Frankfort, Sculpture of the Third Millennium B.C. from Tell Asmar and Khafajah, Oriental Institute Publication 44, 1939

- ^ [10] Henri Frankfort, More Sculpture from the Diyala Region, Oriental Institute Publications 60, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1943

- ^ Martin, Richard. Discoveries in Anatolia, 1930-31.

Sources[]

- Claudia E. Suter, The Victory Stele of Dadusha of Eshnunna: A New Look at its Unusual Culminating Scene, Ash-sharq Bulletin of the Ancient Near East Archaeological, Historical and Societal Studies, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 1-29, 2018

- Chubb, Mary (1999). City In the Sand (2nd ed.). Libri. ISBN 1-901965-02-3.

- Clemens Reichel, Centre and Periphery—the Role of the ‘Palace of the Rulers’ at Tell Asmar in the History of Ešnunna (2,100 –1,750 BCE), Journal of the Canadian Society for Mesopotamian Studies, 2018

- [11] R. M. Whiting Jr., "Old Babylonian Letters from Tell Asmar", Assyriological Studies 22, Oriental Institute, 1987

- [12] I.J. Gelb, "Sargonic Texts from the Diyala Region", Materials for the Assyrian Dictionary, vol. 1, Chicago, 1961

- Maria deJong Ellis, "Notes on the Chronology of the Later Eshnunna Dynasty", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 61–85, 1985

- I. J. Gelb, "A Tablet of Unusual Type from Tell Asmar", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 219–226, 1942

- Romano, Licia, "Who was Worshipped in the Abu Temple at Tell Asmar?", KASKAL 7, pp. 51–65, 2010

- [13] Pinhas Delougaz, "Pottery from the Diyala Region", Oriental Institute Publications 63, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1952, ISBN 0-226-14233-7

- [14] Pinhas Delougaz, Harold D. Hill, and Seton Lloyd, "Private Houses and Graves in the Diyala Region", Oriental Institute Publications 88, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1967

- [15] Pinhas Delougaz and Seton Lloyd with chapters by Henri Frankfort and Thorkild Jacobsen, "Pre-Sargonid Temples in the Diyala Region", Oriental Institute Publications 58, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1942

External links[]

- Populated places established in the 3rd millennium BC

- Populated places disestablished in the 2nd millennium BC

- States and territories established in the 3rd millennium BC

- States and territories disestablished in the 18th century BC

- Early Dynastic Period (Mesopotamia)

- Sumerian cities

- Archaeological sites in Iraq

- Former populated places in Iraq

- Diyala Governorate

- City-states

- Razed cities