Early Dynastic Period (Mesopotamia)

| |

| Geographical range | Mesopotamia |

|---|---|

| Period | Bronze Age |

| Dates | fl. c. 2900–2350 BC (middle) |

| Type site | Tell Khafajah, Tell Agrab, Tell Asmar |

| Major sites | Tell Abu Shahrain, Tell al-Madain, Tell as-Senkereh, Tell Abu Habbah, Tell Fara, Tell Uheimir, Tell al-Muqayyar, Tell Bismaya, Tell Hariri |

| Preceded by | Jemdet Nasr Period |

| Followed by | Akkadian Period |

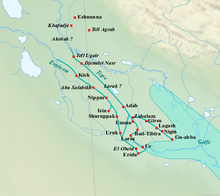

The Early Dynastic period (abbreviated ED period or ED) is an archaeological culture in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) that is generally dated to c. 2900–2350 BC and was preceded by the Uruk and Jemdet Nasr periods. It saw the development of writing and the formation of the first cities and states. The ED itself was characterized by the existence of multiple city-states: small states with a relatively simple structure that developed and solidified over time. This development ultimately led to the unification of much of Mesopotamia under the rule of Sargon, the first monarch of the Akkadian Empire. Despite this political fragmentation, the ED city-states shared a relatively homogeneous material culture. Sumerian cities such as Uruk, Ur, Lagash, Umma, and Nippur located in Lower Mesopotamia were very powerful and influential. To the north and west stretched states centered on cities such as Kish, Mari, Nagar, and Ebla.

The study of Central and Lower Mesopotamia has long been given priority over neighboring regions. Archaeological sites in Central and Lower Mesopotamia—notably Girsu but also Eshnunna, Khafajah, Ur, and many others—have been excavated since the 19th century. These excavations have yielded cuneiform texts and many other important artifacts. As a result, this area was better known than neighboring regions, but the excavation and publication of the archives of Ebla have changed this perspective by shedding more light on surrounding areas, such as Upper Mesopotamia, western Syria, and southwestern Iran. These new findings revealed that Lower Mesopotamia shared many socio-cultural developments with neighboring areas and that the entirety of the ancient Near East participated in an exchange network in which material goods and ideas were being circulated.

History of research[]

Dutch archaeologist Henri Frankfort coined the term Early Dynastic (ED) period for Mesopotamia, the naming convention having been borrowed from the similarly named Early Dynastic (ED) period for Egypt.[2] The periodization was developed in the 1930s during excavations that were conducted by Henri Frankfort on behalf of the University of Chicago Oriental Institute at the archaeological sites of Tell Khafajah, Tell Agrab, and Tell Asmar in the Diyala Region of Iraq.[3]

The ED was divided into the sub-periods ED I, II, and III. This was primarily based on complete changes over time in the plan of the Abu Temple of Tell Asmar, which had been rebuilt multiple times on exactly the same spot.[3] During the 20th century, many archaeologists also tried to impose the scheme of ED I–III upon archaeological remains excavated elsewhere in both Iraq and Syria, dated to 3000–2000 BC. However, evidence from sites elsewhere in Iraq has shown that the ED I–III periodization, as reconstructed for the Diyala river valley region, could not be directly applied to other regions.

Research in Syria has shown that developments there were quite different from those in the Diyala river valley region or southern Iraq, rendering the traditional Lower Mesopotamian chronology useless. During the 1990s and 2000s, attempts were made by various scholars to arrive at a local Upper Mesopotamian chronology, resulting in the Early Jezirah (EJ) 0–V chronology that encompasses everything from 3000 to 2000 BC.[2] The use of the ED I–III chronology is now generally limited to Lower Mesopotamia, with the ED II sometimes being further restricted to the Diyala river valley region or discredited altogether.[2][3]

Periodization[]

The ED was preceded by the Jemdet Nasr and then succeeded by the Akkadian period, during which, for the first time in history, large parts of Mesopotamia were united under a single ruler. The entirety of the ED is now generally dated to approximately 2900–2350 BC according to the middle chronology or 2800–2230 BC according to the short chronology.[2][4] The ED was divided into the ED I, ED II, ED IIIa, and ED IIIb sub-periods. ED I–III were more or less contemporary with the Early Jezirah (EJ) I–III in Upper Mesopotamia.[2] The exact dating of the ED sub-periods varies between scholars—with some abandoning ED II and using only Early ED and Late ED instead and others extending ED I while allowing ED III begin earlier so that ED III was to begin immediately after ED I with no gap between the two.[2][3][5][6]

Many historical periods in the Near East are named after the dominant political force at that time, such as the Akkadian or Ur III periods. This is not the case for the ED period. It is an archaeological division that does not reflect political developments, and it is based upon perceived changes in the archaeological record, e.g. pottery and glyptics. This is because the political history of the ED is unknown for most of its duration. As with the archaeological subdivision, the reconstruction of political events is hotly debated among researchers.

| Period | Middle Chronology All dates BC |

Short Chronology All dates BC |

|---|---|---|

| ED I | 2900–2750/2700 | 2800–2600 |

| ED II | 2750/2700–2600 | 2600–2500 |

| ED IIIa | 2600–2500/2450 | 2500–2375 |

| ED IIIb | 2500/2450–2350 | 2375–2230 |

The ED I (2900–2750/2700 BC) is poorly known, relative to the sub-periods that followed it. In Lower Mesopotamia, it shared characteristics with the final stretches of the Uruk (c. 3300–3100 BC) and Jemdet Nasr (c. 3100–2900 BC) periods.[8] ED I is contemporary with the culture of the Scarlet Ware pottery typical of sites along the Diyala in Lower Mesopotamia, the Ninevite V culture in Upper Mesopotamia, and the Proto-Elamite culture in southwestern Iran.[citation needed]

New artistic traditions developed in Lower Mesopotamia during the ED II (2750/2700–2600 BC). These traditions influenced the surrounding regions. According to later Mesopotamian historical tradition, this was the time when legendary mythical kings such as Lugalbanda, Enmerkar, Gilgamesh, and Aga ruled over Mesopotamia. Archaeologically, this sub-period has not been well-attested to in excavations of Lower Mesopotamia, leading some researchers to abandon it altogether.[9]

The ED III (2600–2350 BC) saw an expansion in the use of writing and increasing social inequality. Larger political entities developed in Upper Mesopotamia and southwestern Iran. ED III is usually further subdivided into the ED IIIa (2600–2500/2450 BC) and ED IIIb (2500/2450–2350 BC). The Royal Cemetery at Ur and the archives of Fara and Abu Salabikh date back to ED IIIa. The ED IIIb is especially well known through the archives of Girsu (part of Lagash) in Iraq and Ebla in Syria.

The end of the ED is not defined archaeologically but rather politically. The conquests of Sargon and his successors upset the political equilibrium throughout Iraq, Syria, and Iran. The conquests lasted many years into the reign of Naram-Sin of Akkad and built on ongoing conquests during the ED. The transition is much harder to pinpoint within an archaeological context. It is virtually impossible to date a particular site as being that of either ED III or Akkadian period using ceramic or architectural evidence alone.[10][11][12][13]

Early Dynastic kingdoms and rulers[]

The Early Dynastic period is preceded by the Uruk Period (ca. 4000—3100 BCE) and the Jemdet Nasr period (ca. 3100—2900 BCE). A full list of rulers, some of them legendary, is given by the Sumerian King List (SKL).

| Dynasties | Dates | Main rulers | Cities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antediluvian kings | Legendary | Alulim, Dumuzid the Shepherd, En-men-dur-ana, Ziusudra | |

| 1st Dynasty of Kish | ca. 2900-2600 BCE | Etana, Enmebaragesi | |

| 1st Dynasty of Uruk | Enmerkar, Lugalbanda, Dumuzid the Fisherman, Gilgamesh | ||

| 1st Dynasty of Ur | ca. 2500-2400 BCE | Meskalamdug, Mesannepada, Puabi | |

| 2nd Dynasty of Uruk | Enshakushanna | ||

| 1st Dynasty of Lagash | ca. 2500-2300 BCE | Ur-Nanshe, Eannatum, En-anna-tum I, Entemena, Urukagina | |

| Dynasty of Adab | Lugal-Anne-Mundu | ||

| 3rd Dynasty of Kish | ca. 2500-2330 BC | Kubaba | |

| 3rd Dynasty of Uruk | ca. 2294 - 2270 BCE | Lugal-zage-si |

The Early Dynastic period is followed by the rise of the Akkadian Empire.

Geographical context[]

Lower Mesopotamia[]

The preceding Uruk period in Lower Mesopotamia saw the appearance of the first cities, early state structures, administrative practices, and writing. Evidence for these practices was attested to during the Early Dynastic period.

The ED period is the first for which it is possible to say something about the ethnic composition of the population of Lower Mesopotamia. This is due to the fact that texts from this period contained sufficient phonetic signs to distinguish separate languages. They also contained personal names, which can potentially be linked to an ethnic identity. The textual evidence suggested that Lower Mesopotamia during the ED period was largely dominated by Sumer and primarily occupied by the Sumerian people, who spoke a non-Semitic language isolate (Sumerian). It is debated whether Sumerian was already in use during the Uruk period.[15]

Textual evidence indicated the existence of a Semitic population in the upper reaches of Lower Mesopotamia. The texts in question contained personal names and words from a Semitic language, identified as Old Akkadian. However, the use of the term Akkadian before the emergence of the Akkadian Empire is problematic[why?], and it has been proposed to refer to this Old Akkadian phase as being of the "Kish civilization" named after Kish (the seemingly most powerful city during the ED period) instead.[16][17][18] Political and socioeconomic structures in these two regions also differed, although Sumerian influence is unparalleled during the Early Dynastic period.

Agriculture in Lower Mesopotamia relied on intensive irrigation. Cultivars included barley and date palms in combination with gardens and orchards. Animal husbandry was also practiced, focusing on sheep and goats.[19] This agricultural system was probably the most productive in the entire ancient Near East. It allowed the development of a highly urbanized society. It has been suggested that, in some areas of Sumer, the population of the urban centers during ED III represented three-quarters of the entire population.[20][21]

The dominant political structure was the city-state in which a large urban center dominated the surrounding rural settlements. The territories of these city-states were in turn delimited by other city-states that were organized along the same principles. The most important centers were Uruk, Ur, Lagash, Adab, and Umma-Gisha. Available texts from this period point to recurring conflicts between neighboring kingdoms, notably between Umma and Lagash.

The situation may have been different further north, where Semitic people seem to have been dominant. In this area, Kish was possibly the center of a large territorial state, competing with other powerful political entities such as Mari and Akshak.[15][22]

The Diyala River valley is another region for which the ED period is relatively well-known. Along with neighboring areas, this region was home to Scarlet Ware—a type of painted pottery characterized by geometric motifs representing natural and anthropomorphic figures. In the Jebel Hamrin, fortresses such as Tell Gubba and Tell Maddhur were constructed. It has been suggested[by whom?] that these sites were established to protect the main trade route from the Mesopotamian lowlands to the Iranian plateau. The main Early Dynastic sites in this region are Tell Asmar and Khafajah. Their political structure is unknown, but these sites were culturally influenced by the larger cities in the Mesopotamian lowland.[8][23][24]

Neighboring regions[]

Upper Mesopotamia and Central Syria[]

At the beginning of the third millennium BC, the Ninevite V culture flourished in Upper Mesopotamia and the Middle Euphrates River region. It extended from Yorghan Tepe in the east to the Khabur Triangle in the west. Ninevite V was contemporary with ED I and marked an important step in the urbanization of the region.[23][25] The period seems to have experienced a phase of decentralization, as reflected by the absence of large monumental buildings and complex administrative systems similar to what had existed at the end of the fourth millennium BC.

Starting in 2700 BC and accelerating after 2500, the main urban sites grew considerably in size and were surrounded by towns and villages that fell inside their political sphere of influence. This indicated that the area was home to many political entities. Many sites in Upper Mesopotamia, including Tell Chuera and Tell Beydar, shared a similar layout: a main tell surrounded by a circular lower town. German archaeologist Max von Oppenheim called them Kranzhügel, or “cup-and-saucer-hills”.[citation needed] Among the important sites of this period are Tell Brak (Nagar), Tell Mozan, Tell Leilan, and Chagar Bazar in the Jezirah and Mari on the middle Euphrates.[26]

Urbanization also increased in western Syria, notably in the second half of the third millennium BC. Sites like Tell Banat, Tell Hadidi, Umm el-Marra, Qatna, Ebla, and Al-Rawda developed early state structures, as evidenced by the written documentation of Ebla. Substantial monumental architecture such as palaces, temples, and monumental tombs appeared in this period. There is also evidence for the existence of a rich and powerful local elite.[27]

The two cities of Mari and Ebla dominate the historical record for this region. According to the excavator of Mari, the circular city on the middle Euphrates was founded ex nihilo at the time of the Early Dynastic I period in Lower Mesopotamia.[19][28][29] Mari was one of the main cities of the Middle East during this period, and it fought many wars against Ebla during the 24th century BC. The archives of Ebla, capital city of a powerful kingdom during the ED IIIb period, indicated that writing and the state were well-developed, contrary to what had been believed about this area before its discovery. However, few buildings from this period have been excavated at the site of Ebla itself.[19][28][30]

The territories of these kingdoms were much larger than in Lower Mesopotamia. Population density, however, was much lower than in the south where subsistence agriculture and pastoralism were more intensive. Towards the west, agriculture takes on more "Mediterranean" aspects: the cultivation of olive and grape was very important in Ebla. Sumerian influence was notable in Mari and Ebla. At the same time, these regions with a Semitic population shared characteristics with the Kish civilization while also maintaining their own unique cultural traits.[16][17][18]

Iranian Plateau[]

In southwestern Iran, the first half of the Early Dynastic period corresponded with the Proto-Elamite period. This period was characterized by indigenous art, a script that has not yet been deciphered, and an elaborate metallurgy in the Lorestan region. This culture disappeared toward the middle of the third millennium, to be replaced by a less sedentary way of life. Due to the absence of written evidence and a lack of archaeological excavations targeting this period, the socio-political situation of Proto-Elamite Iran is not well understood. Mesopotamian texts indicated that the Sumerian kings dealt with political entities in this area. For example, legends relating to the kings of Uruk referred to conflicts against Aratta. As of 2017 Aratta had not been identified, but it is believed to have been located somewhere in southwestern Iran.[citation needed]

In the middle third millennium BC, Elam emerged as a powerful political entity in the area of southern Lorestan and northern Khuzestan.[31][22] Susa (level IV) was a central place in Elam and an important gateway between southwestern Iran and southern Mesopotamia. Hamazi was located in the Zagros Mountains to the north or east of Elam, possibly between the Great Zab and the Diyala River, near Halabja.[22]

This is also the area where the still largely unknown Jiroft culture emerged in the third millennium BC, as evidenced by excavation and looting of archaeological sites.[32] The areas further north and to the east were important participants in the international trade of this period due to the presence of tin (central Iran and the Hindu Kush) and lapis lazuli (Turkmenistan and northern Afghanistan). Settlements such as Tepe Sialk, Tureng Tepe, Tepe Hissar, Namazga-Tepe, Altyndepe, Shahr-e Sukhteh, and Mundigak served as local exchange and production centres but do not seem to have been capitals of larger political entities.[28][33][34]

Persian Gulf[]

The further development of maritime trade in the Persian Gulf led to increased contacts between Lower Mesopotamia and other regions. Starting in the previous period, the area of modern-day Oman—known in ancient texts as Magan—had seen the development of the oasis settlement system. This system relied on irrigation agriculture in areas with perennial springs. Magan owed its good position in the trade network to its copper deposits. These deposits were located in the mountains, notably near Hili, where copper workshops and monumental tombs testifying to the area's affluence has been excavated.

Further to the west was an area called Dilmun, which in later periods corresponds to what is today known as Bahrain. However, while Dilmun was mentioned in contemporary ED texts, no sites from this period have been excavated in this area. This may indicate that Dilmun may have referred to the coastal areas that served as a place of transit for the maritime trade network.[8][28]

Indus valley[]

The maritime trade in the Gulf extended as far east as the Indian subcontinent, where the Indus Valley Civilisation flourished.[28] This trade intensified during the third millennium and reached its peak during the Akkadian and Ur III periods.

The artifacts found in the royal tombs of the First Dynasty of Ur indicate that foreign trade was particularly active during this period, with many materials coming from foreign lands, such as Carnelian likely coming from the Indus or Iran, Lapis Lazuli from Afghanistan, silver from Turkey, copper from Oman, and gold from several locations such as Egypt, Nubia, Turkey or Iran.[36] Carnelian beads from the Indus were found in Ur tombs dating to 2600–2450, in an example of Indus-Mesopotamia relations.[37] In particular, carnelian beads with an etched design in white were probably imported from the Indus Valley, and made according to a technique developed by the Harappans.[35] These materials were used in the manufacture of ornamental and ceremonial objects in the workshops of Ur.[36]

The First Dynasty of Ur had enormous wealth as shown by the lavishness of its tombs. This was probably due to the fact that Ur acted as the main harbour for trade with India, which put her in a strategic position to import and trade vast quantities of gold, carnelian or lapis lazuli.[38] In comparison, the burials of the kings of Kish were much less lavish.[38] High-prowed Summerian ships may have traveled as far as Meluhha, thought to be the Indus region, for trade.[38]