Khafajah

Tutub | |

Shown within Iraq | |

| Alternative name | Khafaje |

|---|---|

| Location | Diyala Province, Iraq |

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 33°21′16.83″N 44°33′20.71″E / 33.3546750°N 44.5557528°ECoordinates: 33°21′16.83″N 44°33′20.71″E / 33.3546750°N 44.5557528°E |

| Type | tell |

Khafajah or Khafaje (Arabic: خفاجة; ancient Tutub, Arabic: توتوب) is an archaeological site in Diyala Province (Iraq). It was part of the city-state of Eshnunna. The site lies 7 miles (11 km) east of Baghdad and 12 miles (19 km) southwest of Eshnunna.

History of archaeological research[]

Khafajah was excavated for 7 seasons in the early 1930s primarily by an Oriental Institute of Chicago team led by Henri Frankfort with Thorkild Jacobsen and Pinhas Delougaz. For two seasons, the site was worked by a joint team of the American Schools of Oriental Research and the University of Pennsylvania.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9]

Khafajah and its environment[]

Khafajah lies on the Diyala River, a tributary of the Tigris.[10] The site consists of four mounds, labeled A through D. The main one, Mound A, extends back as far as the Uruk period and contained an oval temple, a temple of the god Sin, not surely and a temple of Nintu. The Dur-Samsuiluna fort was found on mounds B and C. Mound D contained private homes and a temple for the god Sin where the archive tablets where found in two heaps.[11]

Occupation history[]

Khafajah was occupied during the Early Dynastic Period, through the Sargonid Period, then came under the control of Eshnunna after the fall of the Ur III Empire. Later, after Eshnunna was captured by Babylon, a fort was built at the site by Samsu-iluna of the First Babylonian dynasty and named Dur-Samsuiluna. Mesopotamian chariots were created in Tutub.[13]

| Ruler | Proposed reign | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Abdi-Erah | circa 1820 BC | Ruler of Eshnunna, Contemporary of Sumu-abum of Babylon |

| Adi-madar | Ruler of Eshnunna | |

| Sumina-arim | ||

| Iku-pi-Sin | ||

| Isme-bali | ||

| Tattanum | Contemporary of Belakum of Eshnunna | |

| Hammi-dusur | circa 1800 BC | Contemporary of Sumu-la-El of Babylon |

| Warassa | Ruler of Eshnunna |

Material culture[]

The history of Khafajah is known in somewhat more detail for a period of several decades as a result of the discovery of 112 clay tablets (one now lost) in a temple of Sin. The tablets constitute part of an official archive and include mostly loan and legal documents. The Oriental Institute of Chicago holds 57 of the tablets with the remainder being in the Iraq Museum.[14] Some Early Dynastic Sumerian statues from Khafajah are on the Oriental Institute's list of Lost Treasures from Iraq (after April 9, 2003); however, they have been housed at the Sulaymaniyah Museum since 1961 (see the gallery below).[15][16][17][18]

Gallery[]

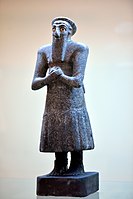

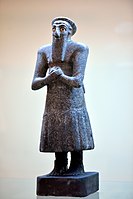

The Iraq Museum's Sumerian Gallery displays several Sumerian statues from the Temple of Sin and the Temple of Nintu (V and VI), including part of a hoard found at the Nintu Temple.

Female worshiper, Sin Temple, Khafajah, Iraq Museum

Female worshiper, Sin Temple, Khafajah, Iraq Museum

Statue from the Sin Temple, Khafajah, Iraq Museum

Statue from the Temple of Sin at Khafajah, Iraq Museum

Statue from the Hoard of Nintu Temple V at Khafajah, Iraq Museum

Statue from the Hoard of Nintu Temple V at Khafajah, Iraq Museum

Male statue from Hoard in Nintu Temple V at Khafajah, Iraq Museum

Statue from Nintu Temple VI at Khafajah, Iraq Museum

Male statuette, Nintu Temple VI, Khafajah, Iraq Museum

Male statuette, Sin Temple IX, Khafajah, Iraq Museum

Male statuette, Nintu Temple VI, Khafajah, Iraq Museum

Limestone human head found at Khafajah, Early Dynastic II (c. 2700 BC)

Cylinder seal found at Khafajah, Jemdet Nasr period, (3100–2900 BC)

Three Sumerian statues, Early Dynastic Period, 2900-2350 BCE, from Khafajah, Iraq. The Sulaymaniyah Museum

Head of a Sumerian female, from Khafajah, excavated by the Oriental Institute, Early Dynastic III, c. 2400 BCE. The Sulaymaniyah Museum

Headless statue of a Sumerian man, from Khafajah, Early Dynastic Period, 2900-2350 BCE. The Sulaymaniyah Museum

See also[]

- Cities of the ancient Near East

References[]

- ^ [1] The Diyala Project at the University of Chicago

- ^ [2] OIC 13. Tell Asmar and Khafaje: The First Season's Work in Eshnunna 1930/31, Henri Frankfort, Thorkild Jacobsen, and Conrad Preusser, 1932

- ^ [3] OIC 16. Tell Asmar, Khafaje and Khorsabad: Second Preliminary Report of the Iraq Expedition, Henri Frankfort, 1933

- ^ [4] OIC 17. Iraq Excavations of the Oriental Institute 1932/33: Third Preliminary Report of the Iraq Expedition, Henri Frankfort, 1934

- ^ [5] OIC 19. Oriental Institute Discoveries in Iraq, 1933/34: Fourth Preliminary Report of the Iraq Expedition, Henri Frankfort with a chapter by Thorkild Jacobsen, 1935

- ^ [6] OIC 20. Progress of the Work of the Oriental Institute in Iraq, 1934/35: Fifth Preliminary Report of the Iraq Expedition, Henri Frankfort, 1936

- ^ [7] OIP 44. Sculpture of the Third Millennium B.C. from Tell Asmar and Khafajah, Henri Frankfort, 1939

- ^ [8] OIP 53. The Temple Oval at Khafajah, Pinhas Delougaz, with a chapter by Thorkild Jacobsen. 1940 (also as ISBN 0-226-14234-5)

- ^ Parrot, André (1960). Sumer. Thames and Hudson.

- ^ Black, Jeremy A. (2006). The Literature of Ancient Sumer. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-929633-0.

- ^ Hansen, Donald P. (2002). Leaving No Stones Unturned: Essays on the Ancient Near East and Egypt in Honor of Donald P. Hansen. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-055-2.

- ^ "Khafajeh jar". British Museum.

- ^ Editors, Helicon; Mellersh, H. E. L.; Williams, Neville; Publishing, Helicon (1999). Chronology of World History: The ancient and medieval world, prehistory-AD 1491. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-155-7.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ Harris Rivkah, The Archive of the Sin Temple in Khafajah (Tutub)", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 9 no. 2, 1955

- ^ "Lost Treasures from Iraq". Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ "Lost Treasures from Iraq". Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ "Lost Treasures from Iraq". Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- ^ Amin, Osama S. M. "Lost Treasures from Iraq: Revisited and Identified". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 11 December 2018.

Further reading[]

- Old Babylonian Public Buildings in the Diyala Region: Part 1 : Excavations at Ishchali, Part 2 : Khafajah Mounds B, C, and D (Publication Series 98), Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 1990, ISBN 0-918986-62-1

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Khafajah. |

- Oriental Institute slides of the site

- Archaeology of Khafah write-up at Brown University

- Two wrestlers balancing vessels (jars) on their heads- ca. 2600 B.C at Oriental Institute

- Bowl with mosaic inlays on outside - ca. 3000 B.C at Oriental Institute

- Plaque, decorated with three registers of relief, showing banquet scene with musicians - ca. 2600 B.C at Oriental Institute

- 1930s archaeological discoveries

- Archaeological sites in Iraq

- Former populated places in Iraq

- Diyala Governorate

- Early Dynastic Period (Mesopotamia)

- Uruk period