Finance

hideThis article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Finance |

|---|

|

|

Finance is a term for matters regarding the management, creation, and study of money and investments.[1] [note 1] Specifically, it deals with the questions of how an individual, company or government acquires money – called capital in the context of a business – and how they spend or invest that money.[2] Finance is then often divided into the following broad categories: personal finance, corporate finance, and public finance.[1]

At the same time, and correspondingly, finance is about the overall "system" [1] i.e., the financial markets that allow the flow of money, via investments and other financial instruments, between and within these areas; this "flow" is facilitated by the financial services sector. Finance therefore refers to the study of the securities markets, including derivatives, and the institutions that serve as intermediaries to those markets, thus enabling the flow of money through the economy.[3]

A major focus within finance is thus investment management – called money management for individuals, and asset management for institutions – and finance then includes the associated activities of securities trading and stock broking, investment banking, financial engineering, and risk management. Fundamental to these areas is the valuation of assets such as stocks, bonds, loans, but also, by extension, entire companies.[4]

Although they are closely related, the disciplines of economics and finance are distinct. The economy is a social institution that organizes a society's production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services, all of which must be financed.

Given its wide scope, finance is studied in several academic disciplines, and, correspondingly, there are several related professional qualifications that can lead to the field.

History of finance[]

The origin of finance can be traced to the start of civilization. The earliest historical evidence of finance is dated to around 3000 BC. Banking originated in the Babylonian empire, where temples and palaces were used as safe places for the storage of valuables. Initially, the only valuable that could be deposited was grain, but cattle and precious materials were eventually included. During the same period, the Sumerian city of Uruk in Mesopotamia supported trade by lending as well as the use of interest. In Sumerian, “interest” was mas, which translates to "calf". In Greece and Egypt, the words used for interest, tokos and ms respectively, meant “to give birth”. In these cultures, interest indicated a valuable increase, and seemed to consider it from the lender's point of view.[5] The Code of Hammurabi (1792-1750 BC) included laws governing banking operations. The Babylonians were accustomed to charge interest at the rate of 20 per cent per annum.

Jews were not allowed to take interest from other Jews, but they were allowed to take interest from Gentiles, who had at that time no law forbidding them from practising usury. As Gentiles took interest from Jews, the Torah considered it equitable that Jews should take interest from Gentiles. In Hebrew, interest is neshek.

By 1200 BC, Cowrie shells were used as a form of money in China. By 640 BC, the Lydians had started to use coin money. Lydia was the first place where permanent retail shops opened. (Herodotus mentions the use of crude coins in Lydia in an earlier date, around 687 BC.)[6][7]

The use of coins as a means of representing money began in the years between 600 and 570 BCE. Cities under the Greek empire, such as Aegina (595 BCE), Athens (575 BCE) and Corinth (570 BCE), started to mint their own coins. In the Roman Republic, interest was outlawed altogether by the Lex Genucia reforms. Under Julius Caesar, a ceiling on interest rates of 12% was set, and later under Justinian it was lowered even further to between 4% and 8%.[citation needed]

The financial system[]

As above, the financial system consists of the flows of capital that take place between individuals (personal finance), governments (public finance), and businesses (corporate finance). "Finance" thus studies the process of channeling money from savers and investors to entities that need it. Savers and investors have money available which could earn interest or dividends if put to productive use. Individuals, companies and governments must obtain money from some external source, such as loans or credit, when they lack sufficient funds to operate.

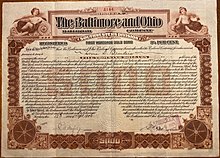

In general, an entity whose income exceeds its expenditure can lend or invest the excess, intending to earn a fair return. Correspondingly, an entity where income is less than expenditure can raise capital usually in one of two ways: (i) by borrowing in the form of a loan (private individuals), or by selling government or corporate bonds; (ii) by a corporate selling equity, also called stock or shares (may take various forms: preferred stock or common stock). The owners of both bonds and stock may be institutional investors – financial institutions such as investment banks and pension funds – or private individuals, called private investors or retail investors.

The lending is often indirect, through a financial intermediary such as a bank, or via the purchase of notes or bonds (corporate bonds, government bonds, or mutual bonds) in the bond market. The lender receives interest, the borrower pays a higher interest than the lender receives, and the financial intermediary earns the difference for arranging the loan.[8][9][10] A bank aggregates the activities of many borrowers and lenders. A bank accepts deposits from lenders, on which it pays interest. The bank then lends these deposits to borrowers. Banks allow borrowers and lenders, of different sizes, to coordinate their activity.

Investing typically entails the purchase of stock, either individual securities, or via a mutual fund for example. Stocks are usually sold by corporations to investors so as to raise required capital in the form of "equity financing", as distinct from the debt financing described above. The financial intermediaries here are the investment banks. The investment banks find the initial investors and facilitate the listing of the securities, such as equity and debt. Additionally, they facilitate the securities exchanges, which allow their trade thereafter, as well as the various service providers which manage the performance or risk of these investments.

Areas of finance[]

Personal finance[]

Personal finance[11] is defined as "the mindful planning of monetary spending and saving, while also considering the possibility of future risk". Personal finance may involve paying for education, financing durable goods such as real estate and cars, buying insurance, investing, and saving for retirement.[12] Personal finance may also involve paying for a loan or other debt obligations. The main areas of personal finance are considered to be income, spending, saving, investing, and protection.[13] The following steps, as outlined by the Financial Planning Standards Board,[14] suggest that an individual will understand a potentially secure personal finance plan after:

- Purchasing insurance to ensure protection against unforeseen personal events;

- Understanding the effects of tax policies, subsidies, or penalties on the management of personal finances;

- Understanding the effects of credit on individual financial standing;

- Developing a savings plan or financing for large purchases (auto, education, home);

- Planning a secure financial future in an environment of economic instability;

- Pursuing a checking and/or a savings account;

- Preparing for retirement or other long term expenses.[15]

Corporate finance[]

Corporate finance deals with the sources of funding and the capital structure of corporations, the actions that managers take to increase the value of the firm to the shareholders, and the tools and analysis used to allocate financial resources. Short term financial management is often termed "working capital management", and relates to cash, inventory and debtors management. The goal is to ensure that the firm has sufficient cash flow for ongoing operations, to service long-term debt, and to satisfy both maturing short-term debt and upcoming operational expenses. In the longer term, corporate finance generally involves balancing risk and profitability, while attempting to maximize an entity's assets, net incoming cash flow and the value of its stock. This entails three primary areas:

- Capital budgeting: selecting which projects to invest in (here, accurately determining value is crucial as judgements about asset values can be "make or break"[4]);

- Dividend policy: the use of "excess" capital;

- Sources of capital: which funding is to be used.

The latter creates the link with investment banking and securities trading, in that the capital raised will generically comprise debt, i.e. corporate bonds, and equity, often listed shares.

While corporate finance is in principle different from managerial finance, which studies the financial management of all firms rather than corporations alone, the main concepts in the study of corporate finance are applicable to the financial problems of all kinds of firms. Although financial management overlaps with the financial function of the accounting profession, financial accounting is the reporting of historical financial information, whereas as discussed, financial management is concerned with increasing the firm's Shareholder value and increasing their rate of return on the investment. In this context, Financial risk management is about protecting the firm's economic value by using financial instruments to manage exposure to risk, particularly credit risk and market risk, often arising from the firm's funding structures.

Public finance[]

Public finance describes finance as related to sovereign states, sub-national entities, and related public entities or agencies. It generally encompasses a long-term strategic perspective regarding investment decisions that affect public entities.[16] These long-term strategic periods typically encompass five or more years.[17] Public finance is primarily concerned with:

- Identification of required expenditure of a public sector entity;

- Source(s) of that entity's revenue;

- The budgeting process;

- Debt issuance, or municipal bonds, for public works projects.

Central banks, such as the Federal Reserve System banks in the United States and Bank of England in the United Kingdom, are strong players in public finance. They act as lenders of last resort as well as strong influences on monetary and credit conditions in the economy.[18]

Financial theory[]

Financial theory is studied and developed within the disciplines of management, (financial) economics, accountancy and applied mathematics. Abstractly, finance is concerned with the investment and deployment of assets and liabilities over "space and time"; i.e. it is about performing valuation and asset allocation today, based on risk and uncertainty of future outcomes while appropriately incorporating the time value of money. Determining the present value of these future values, "discounting", must be at the risk-appropriate discount rate, in turn, a major focus of finance-theory.[2] Since the debate as to whether finance is an art or a science is still open,[19] there have been recent efforts to organize a list of unsolved problems in finance.

Financial economics[]

Financial economics is the branch of economics that studies the interrelation of financial variables, such as prices, interest rates and shares, as opposed to real economic variables, i.e. goods and services. It thus centers on pricing, decision making and risk management in the financial markets, and produces many of the commonly employed financial models. (Financial econometrics is the branch of financial economics that uses econometric techniques to parameterize the relationships suggested.)

The discipline has two main areas of focus: asset pricing and (theoretical) corporate finance; the first being the perspective of providers of capital, i.e. investors, and the second of users of capital. Respectively:

- Asset pricing theory develops the models used in determining the risk appropriate discount rate, and in pricing derivatives. The analysis essentially explores how rational investors would apply risk and return to the problem of investment under uncertainty. The twin assumptions of rationality and market efficiency lead to modern portfolio theory (the CAPM), and to the Black–Scholes theory for option valuation. At more advanced levels - and often in response to financial crises - the study then extends these "Neoclassical" models to incorporate phenomena where their assumptions do not hold, or to more general settings.

- Much of corporate finance theory, by contrast, considers investment under "certainty" (Fisher separation theorem, "theory of investment value", Modigliani–Miller theorem). Here theory and methods are developed for the decisioning re funding, dividends, and capital structure discussed above. A recent development is to incorporate uncertainty and contingency - and thus various elements of asset pricing - into these decisions, employing for example real options analysis.

Financial mathematics[]

Financial mathematics is a field of applied mathematics concerned with financial markets. The subject has a close relationship with the discipline of financial economics, which is concerned with much of the underlying theory that is involved in financial mathematics. Generally, mathematical finance will derive and extend the mathematical or numerical models suggested by financial economics.

The field is largely focused on the modelling of derivatives — see Outline of finance § Mathematical tools and Outline of finance § Derivatives pricing — although other important subfields include insurance mathematics and quantitative portfolio problems. Relatedly, the techniques developed are applied to pricing and hedging a wide range of asset-backed, government, and corporate-securities.

In terms of practice, mathematical finance overlaps heavily with the field of computational finance, also known as financial engineering. While these are largely synonymous, the latter focuses on application, and the former focuses on modeling and derivation; see Quantitative analyst. There is also a significant overlap with financial risk management.

Experimental finance[]

Experimental finance aims to establish different market settings and environments to experimentally observe and provide a lens through which science can analyze agents' behavior and the resulting characteristics of trading flows, information diffusion, and aggregation, price setting mechanisms, and returns processes. Researchers in experimental finance can study to what extent existing financial economics theory makes valid predictions and therefore prove them, as well as attempt to discover new principles on which such theory can be extended and be applied to future financial decisions. Research may proceed by conducting trading simulations or by establishing and studying the behavior of people in artificial competitive market-like settings.

Behavioral finance[]

Behavioral finance studies how the psychology of investors or managers affects financial decisions and markets, and is relevant when making a decision that can impact either negatively or positively on one of their areas. Behavioral finance has grown over the last few decades to become an integral aspect of finance.[20]

Behavioral finance includes such topics as:

- Empirical studies that demonstrate significant deviations from classical theories;

- Models of how psychology affects and impacts trading and prices;

- Forecasting based on these methods;

- Studies of experimental asset markets and the use of models to forecast experiments.

A strand of behavioral finance has been dubbed quantitative behavioral finance, which uses mathematical and statistical methodology to understand behavioral biases in conjunction with valuation.

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^

The following are definitions of finance as crafted by the authors indicated:

- Fama and Miller: "The theory of finance is concerned with how individuals and firms allocate resources through time."

- F.W. Paish: "Finance may be defined as the position of money at the time it is wanted".[citation needed]

- John J. Hampton: "The term finance can be defined as the management of the flows of money through an organisation, whether it will be a corporation, school, or bank or government agency".[citation needed]

- Howard and Upton: "Finance may be defined as that administrative area or set of administrative functions in an organisation which relates with the arrangement of each debt and credit so that the organisation may have the means to carry out the objectives as satisfactorily as possible".[citation needed]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Staff, Investopedia (2003-11-20). "Finance". Investopedia. Retrieved 2018-11-26.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Finance" Farlex Financial Dictionary. 2012

- ^ Melicher, Ronald and Welshans, Merle (1988). Finance: Introduction to Markets, Institutions & Management (7th ed.). Cincinnatti OBN: Southwestern Publishing Company. p. 2. ISBN 0-538-06160-X.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Irons, Robert (July 2019). The Fundamental Principles of Finance. Google Books: Routledge. ISBN 9781000024357. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Fergusson, Nial. The Ascent of Money. United States: Penguin Books.

- ^ "Herodotus on Lydia". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2021-05-13.

- ^ "babylon-coins.com". babylon-coins.com. Retrieved 2021-05-13.

- ^ Bank of Finland. "Financial system".

- ^ "Introducing the Financial System | Boundless Economics". courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 2020-05-18.

- ^ "What is the financial system?". Economy.

- ^ "Personal Finance - Definition, Overview, Guide to Financial Planning". Corporate Finance Institute. Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- ^ Publishing, Speedy (2015-05-25). Finance (Speedy Study Guides). Speedy Publishing LLC. ISBN 978-1-68185-667-4.

- ^ "Personal Finance - Definition, Overview, Guide to Financial Planning". Corporate Finance Institute. Retrieved 2020-05-18.

- ^ Snowdon, Michael, ed. (2019), "Financial Planning Standards Board", Financial Planning Competency Handbook, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 709–735, doi:10.1002/9781119642497.ch80, ISBN 9781119642497

- ^ Kenton, Will. "Personal Finance". Investopedia. Retrieved 2020-01-20.

- ^ Doss, Daniel; Sumrall, William; Jones, Don (2012). Strategic Finance for Criminal Justice Organizations (1st ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-1439892237.

- ^ Doss, Daniel; Sumrall, William; Jones, Don (2012). Strategic Finance for Criminal Justice Organizations (1st ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-1439892237.

- ^ Board of Governors of Federal Reserve System of the United States. Mission of the Federal Reserve System. Federalreserve.gov Accessed: 2010-01-16. (Archived by WebCite at Archived 2010-01-14 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ "Is finance an art or a science?". Investopedia. Retrieved 2015-11-11.

- ^ Shefrin, Hersh (2002). Beyond greed and fear: Understanding behavioral finance and the psychology of investing. New York: Oxford University Press. p. ix. ISBN 978-0195304213. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

growth of behavioral finance.

External links[]

| Look up finance in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Finance |

Media related to Finance at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Finance at Wikimedia Commons

- Finance