Fish in culture

Culture consists of the social behaviour and norms in human societies transmitted through social learning.[1] Fish play many roles in human culture, from their economic importance in the fishing industry and fish farming, to recreational fishing, folklore, mythology, religion, art, literature, and film.

Context[]

Culture consists of the social behaviour and norms found in human societies and transmitted through social learning. Cultural universals in all human societies include expressive forms like art, music, dance, ritual, religion, and technologies like tool usage, cooking, shelter, and clothing. The concept of material culture covers physical expressions such as technology, architecture and art, whereas immaterial culture includes principles of social organization, mythology, philosophy, literature, and science.[1] This article describes the roles played by fish in human culture, so defined.

For food[]

Throughout history, humans have utilized fish as a food source. Historically and today, most fish protein has come by means of catching wild fish. However, fish farming, which has been practiced since about 3,500 BC in China,[2] is becoming increasingly important in many nations, and by 2016, more than 50% of the seafood brought to market was produced by aquaculture.[3] Overall, about one-sixth of the world's protein is estimated to be provided by fish.[4] Fisheries provide income for millions of people.[4][5]

In recreation[]

Fish have been recognized as a source of beauty for almost as long as used for food, appearing in cave art, being raised as ornamental fish in ponds, and displayed in aquariums in homes, offices, or public settings. Some smaller and more colourful species, and sometimes painted fish, serve as ornamental fish in ponds and aquariums, and as pets.[6]

Angling is fishing for pleasure or competition, with a rod, reel, line, hooks and bait. It has been practised for centuries, providing pleasure and employment.[7]

In science[]

Medaka and zebrafish are used as research models for studies in genetics and developmental biology. The zebrafish is the most commonly used laboratory vertebrate,[6] offering the advantages of similar genetics to mammals, small size, simple environmental needs, transparent larvae permitting non-invasive imaging, plentiful offspring, rapid growth, and the ability to absorb mutagens added to their water.[8]

In literature and film[]

Fish feature prominently in literature and film, as in books such as The Old Man and the Sea. Large fish, particularly sharks, have frequently been the subject of horror films and thrillers, most notably the novel Jaws, which spawned a series of films of the same name. Piranhas are shown in a similar light to sharks in films such as Piranha.[9]

In folklore, religion and mythology[]

Fish themes have symbolic significance in many cultures and religions. In-and-Out Fish Design is a constant theme in the prehistoric and historical art of Iran, which demonstrates two swinging fishes named Kar-Mahi. Ahura Mazda sets these fishes on guard of roots of the tree of life, named Gukaran, so they are eternal sentries of worldly life, in Persian culture.[10]

In ancient Mesopotamia, fish offerings were made to the gods from the very earliest times.[11] Fish were also a major symbol of Enki, the god of water.[11] Fish frequently appear as a filling motif on cylinder seals from the Old Babylonian (c. 1830 BC – c. 1531 BC), usually in close proximity to malevolent forces, such as demons.[11] Neo-Assyrian (911 BC – 609 BC) cylinder seals sometimes show fish resting on tables, which may be altars.[11] The Assyrian King Sennacherib is recorded as having thrown a golden fish into the sea along with another golden object to accompany an offering of a golden boat to Ea (the East Semitic equivalent of Enki).[11] Starting during the Kassite Period (c. 1600 BC – c. 1155 BC), healers and exorcists dressed in ritual garb resembling the bodies of fish.[11] This continued until the early Persian Period (550 BC – 330 BC).[11] During the Seleucid Period (312 BC – 63 BC), the legendary Babylonian culture hero Oannes, described by Berossus, was said to have dressed in the skin of a fish.[11] Fish were sacred to the Syrian goddess Atargatis[12] and, during her festivals, only her priests were permitted to eat them.[12]

In the Book of Jonah, a work of Jewish literature probably written in the fourth century BC, the central figure, a prophet named Jonah, is swallowed by a giant fish after being thrown overboard by the crew of the ship he is travelling on.[14][15][16] The fish later vomits Jonah out on shore after three days.[14][15][16] This book was later included as part of the Hebrew Bible, or Christian Old Testament,[17][18] and a version of the story it contains is summarized in Surah 37:139-148 of the Quran.[19] Early Christians used the ichthys, a symbol of a fish, to represent Jesus,[12][13] because the Greek word for fish, ΙΧΘΥΣ (ichthys), could be used as an acronym for "Ίησοῦς Χριστός, Θεοῦ Υἱός, Σωτήρ" (Iesous Christos, Theou Huios, Soter), meaning "Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour".[12][13]

In the dhamma of Buddhism the fish symbolize happiness as they have complete freedom of movement in the water. Often drawn in the form of carp which are regarded in the Orient as sacred on account of their elegant beauty, size and life-span. Among the deities said to take the form of a fish are Ika-Roa of the Polynesians, Dagon of various ancient Semitic peoples, the shark-gods of Hawaiʻi and Matsya of the Hindus.

Legends of half-human, half-fish mermaids are common in folklore, retold in the stories of Hans Christian Andersen. In British folk tales, mermaids both predict and bring ill fortune.[20]

The astrological symbol Pisces is based on a constellation of the same name, but there is a second fish constellation in the night sky, Piscis Austrinus.[21]

In folk and fairy tales[]

Fish with magical abilities appear in fairy and folk tale traditions all over the world. The international classification of the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index includes number 303, "The Twins or Blood Brothers", as in the Spanish fairy tale The Knights of the Fish, and the Albanian heroic tale The Twins. The story runs that a poor fisherman captures a fish three times; on the third occasion, the fish resigns to its fate and convinces the fisherman to cook and give part of its flesh to his wife, his dogs and his horses. Twin boys are born to the fisherman and his wife, two hounds to the dogs and two foals to the horses; in some versions it is triplets.[22] As another example, tale number 507, "The Monster's Bride", varies the theme of Grateful Dead, as in the Armenian fairy tale of The Golden-Headed Fish. The hero (a fisherman's son, a prince) releases a fish back into the ocean. Some time later, he meets a strange companion and together they liberate a princess from a curse. At the end of the tale, the companion reveals he was the fish.[23] Among the numerous other tales are number 554, "The Grateful Animals";[24] number 555, "The Fisherman and his Wife";[25] and number 675, "The Fool Whose Wishes Always Come True" or "The Lazy Boy".[26]

In art[]

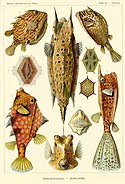

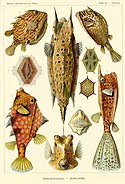

Fish have been frequent subjects in art, reflecting their economic importance, for at least 14,000 years. They were commonly worked into patterns in Ancient Egypt, acquiring mythological significance in Ancient Greece and Rome, and from there into Christianity as a religious symbol; artists in China and Japan similarly use fish images symbolically. Teleosts became common in Renaissance art, with still life paintings reaching a peak of popularity in the Netherlands in the 17th century. In the 20th century, different artists such as Klee, Magritte, Matisse and Picasso used representations of teleosts to express radically different themes, from attractive to violent.[27] The zoologist and artist Ernst Haeckel painted teleosts and other animals in his 1904 Kunstformen der Natur. Haeckel had become convinced by Goethe and Alexander von Humboldt that making accurate depictions of unfamiliar natural forms, such as from the deep oceans, he could not only discover "the laws of their origin and evolution but also to press into the secret parts of their beauty by sketching and painting".[28]

Fish Still Life with Stormy Seas, Willem Ormea and Abraham Willaerts, Dutch Golden Age, 1636

Wall painting of fishing, Tomb of Menna the scribe, Thebes, Ancient Egypt, c. 1422–1411 BC

Silver fish plate, Sevso Treasure, Hungary, 4th-5th century

Italian Renaissance: Fish, Antonio Tanari, c. 1610–1630, in the Medici Villa, Poggio a Caiano

Mandarin Fish by Bian Shoumin, Qing Dynasty, 18th century

Saito Oniwakamaru fights a giant carp at the Bishimon waterfall by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 19th century

Still Life with Mackerel, Lemons and Tomato, Vincent van Gogh, 1886

"Ostraciontes" by Ernst Haeckel, 1904. Ten fish with Lactoria cornuta in centre.

Fish Magic, Paul Klee, oil and watercolour varnished, 1925

See also[]

- Birds in culture

- Insects in culture

- Plants in culture

References[]

- ^ a b Macionis, John J.; Gerber, Linda Marie (2011). Sociology. Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 53. ISBN 978-0137001613. OCLC 652430995.

- ^ Spalding, Mark (July 11, 2013). "Sustainable Ancient Aquaculture". National Geographic. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ "Basic Questions about Aquaculture". Office of Aquaculture. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

- ^ a b Helfman, Gene S. (2007). Fish Conservation: A Guide to Understanding and Restoring Global Aquatic Biodiversity and Fishery Resources. Island Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-1597267601.

- ^ "World Review of Fisheries and Aquaculture" (PDF). fao.org. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ a b Kisia, S. M. (2010). Vertebrates: Structures and Functions. CRC Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-4398-4052-8.

- ^ "New Economic Report Finds Commercial and Recreational Saltwater Fishing Generated More Than Two Million Jobs". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ "Five reasons why zebrafish make excellent research models". NC3RS. 10 April 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- ^ Zollinger, Sue Anne (3 July 2009). "Piranha–Ferocious Fighter or Scavenging Softie?". A Moment of Science. Indiana Public Media. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ Taheri, Sadreddin (2009). "Symbolic Significance of In-and-Out Fish Design in Iranian Carpet". Tehran: Foruzesh Journal, No. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992). Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary. The British Museum Press. pp. 82–83. ISBN 0-7141-1705-6.

- ^ a b c d e Hyde, Walter Woodburn (2008) [1946]. Paganism to Christianity in the Roman Empire. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-1-60608-349-9.

- ^ a b c Coffman, Elesha (8 August 2008). "What is the origin of the Christian fish symbol?". Christianity Today. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ a b Sherwood, Yvonne (2000), A Biblical Text and Its Afterlives: The Survival of Jonah in Western Culture, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–8, ISBN 0-521-79561-3

- ^ a b Ziolkowski, Jan M. (2007). Fairy Tales from Before Fairy Tales: The Medieval Latin Past of Wonderful Lies. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-472-03379-9.

- ^ a b Gaines, Janet Howe (2003). Forgiveness in a Wounded World: Jonah's Dilemma. Atlanta, Georgia: Society of Biblical Literature. pp. 8–9. ISBN 1-58983-077-6.

- ^ Band, Arnold J. (2003). Studies in Modern Jewish Literature. JPS Scholar of Distinction Series. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Jewish Publication Society. pp. 106–107. ISBN 0-8276-0762-8.

- ^ Person, Raymond (1996). In Conversation with Jonah: Conversation Analysis, Literary Criticism, and the Book of Jonah. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press. p. 155. ISBN 1-85075-619-8.

- ^ Vicchio, Stephen J. (2008), Biblical Figures in the Islamic Faith, Eugene, Oregon: Wipf & Stock, p. 67, ISBN 978-1-55635-304-8

- ^ Briggs, K. M. (1976). An Encyclopedia of Fairies, Hobgoblins, Brownies, Boogies, and Other Supernatural Creatures. Random House. p. 287. ISBN 0-394-73467-X.

- ^ "Piscis Austrinus". allthesky.com. The Deep Photographic Guide to the Constellations. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ Aarne, A.; Thompson, S. (1961). The types of the folktale: a classification and bibliography. Helsinki: Folklore Fellows Communications FFC no. 184. Academia Scientiarum Fennica. pp. 95–97.

- ^ Liljeblad, Sven. Die Tobiasgeschichte und andere Märchen mit Toten Helfern. P. Lindstedts Univ.-Bokhandel, 1927. pp. 243ff.

- ^ Uther, Hans-Jörg. Handbuch zu den "Kinder- und Hausmärchen" der Brüder Grimm: Entstehung - Wirkung - Interpretation. Berlin; New York: Walter de Gruyter. 2013. p. 40.

- ^ Aarne, A.; Thompson, S. (1961). The types of the folktale: a classification and bibliography. Helsinki: Folklore Fellows Communications FFC no. 184. Academia Scientiarum Fennica. pp. 200–201.

- ^ Aarne, A.; Thompson, S. (1961). The types of the folktale: a classification and bibliography. Helsinki: Folklore Fellows Communications FFC no. 184. Academia Scientiarum Fennica. pp. 236–237.

- ^ Moyle, Peter B.; Moyle, Marilyn A. (May 1991). "Introduction to fish imagery in art". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 31 (1): 5–23. doi:10.1007/bf00002153. S2CID 33458630.

- ^ Richards, Robert J. "The Tragic Sense of Ernst Haeckel: His Scientific and Artistic Struggles" (PDF). University of Chicago. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

External links[]

Media related to Fish in human culture at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Fish in human culture at Wikimedia Commons

- Fish in popular culture

- Fish in religion