Gene Hackman

Gene Hackman | |

|---|---|

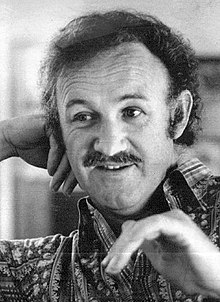

Hackman in 1972 | |

| Born | Eugene Allen Hackman January 30, 1930 San Bernardino, California, U.S. |

| Occupation | Actor, novelist |

| Years active | 1956–2004, 2016-2017 (actor) 1999-2013 (novelist) |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 3 |

| Awards | 2 Academy Awards, 4 Golden Globe Awards, 1 SAG Award, 2 BAFTA Awards. |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/ | |

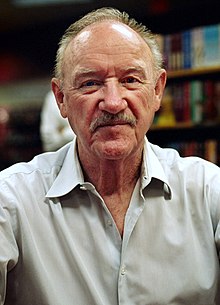

Eugene Allen Hackman[1][2][3] (born January 30, 1930) is an American retired actor, novelist, and United States Marine. In a career that has spanned more than six decades, Hackman has won two Academy Awards, four Golden Globes, one Screen Actors Guild Award, and two BAFTAs.

Nominated for five Academy Awards, Hackman won Best Actor for his role as Jimmy "Popeye" Doyle in the critically acclaimed thriller The French Connection (1971) and Best Supporting Actor as "Little" Bill Daggett in the Clint Eastwood Western Unforgiven (1992). His other nominations for Best Supporting Actor came with the films Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and I Never Sang for My Father (1970), with a second Best Actor nomination for Mississippi Burning (1988).

Hackman's other major film roles included The Poseidon Adventure (1972), The Conversation (1974), French Connection II (1975), A Bridge Too Far (1977), Superman: The Movie (1978)—as arch-villain Lex Luthor, Hoosiers (1986), No Way Out (1987), Bat*21 (1988), The Firm (1993), The Quick and the Dead (1995), Get Shorty (1995), Crimson Tide (1995), Enemy of the State (1998), Antz (1998), The Replacements (2000), Behind Enemy Lines (2001), The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), and Welcome to Mooseport (2004)—his final film role before retirement.

Early life and education[]

Hackman was born in San Bernardino, California, the son of Eugene Ezra Hackman and Anna Lyda Elizabeth (née Gray).[4][5] He has one brother, Richard. He has Pennsylvania Dutch, English, and Scottish ancestry; his mother was Canadian, and was born in Lambton, Ontario.[6][7] His family moved frequently, finally settling in Danville, Illinois, where they lived in the house of his English-born maternal grandmother, Beatrice.[6][8] Hackman's father operated the printing press for the Commercial-News, a local paper.[9] His parents divorced in 1943 and his father subsequently left the family.[8][9] Hackman decided that he wanted to become an actor when he was ten years old.[10]

Hackman lived briefly in Storm Lake, Iowa, and spent his sophomore year at Storm Lake High School.[11] He left home at age 16 and lied about his age to enlist in the United States Marine Corps. He served four and a half years as a field radio operator.[12] He was stationed in China (Qingdao and later in Shanghai). When the Communist Revolution conquered the mainland in 1949, Hackman was assigned to Hawaii and Japan. Following his discharge in 1951,[13] he moved to New York and had several jobs.[12] His mother died in 1962 as a result of a fire she accidentally started while smoking.[14] He began a study of journalism and television production at the University of Illinois under the G.I. Bill, but left and moved back to California.[15]

Acting was something I wanted to do since I was 10 and saw my first movie, I was so captured by the action guys. Jimmy Cagney was my favorite. Without realizing it, I could see he had tremendous timing and vitality.

Gene Hackman[10]

Career[]

Beginnings to the 1960s[]

In 1956, Hackman began pursuing an acting career. He joined the Pasadena Playhouse in California,[12] where he befriended another aspiring actor, Dustin Hoffman.[12] Already seen as outsiders by their classmates, Hackman and Hoffman were voted "The Least Likely To Succeed",[12] and Hackman got the lowest score the Pasadena Playhouse had yet given.[16] Determined to prove them wrong, Hackman moved to New York City. A 2004 article in Vanity Fair described Hackman, Hoffman and Robert Duvall as struggling California-born actors and close friends, sharing NYC apartments in various two-person combinations in the 1960s.[17][18] To support himself between acting jobs, Hackman was working at a Howard Johnson restaurant[19] when he encountered an instructor from the Pasadena Playhouse, who said that his job proved that Hackman "wouldn't amount to anything".[20] A Marine officer who saw him as a doorman said "Hackman, you're a sorry son of a bitch". Rejection motivated Hackman, who said,[19]

it was more psychological warfare, because I wasn't going to let those fuckers get me down. I insisted with myself that I would continue to do whatever it took to get a job. It was like me against them, and in some way, unfortunately, I still feel that way. But I think if you’re really interested in acting there is a part of you that relishes the struggle. It’s a narcotic in the way that you are trained to do this work and nobody will let you do it, so you’re a little bit nuts. You lie to people, you cheat, you do whatever it takes to get an audition, get a job.

Hackman got various bit roles, for example on the TV series Route 66 in 1963, and began performing in several Off-Broadway plays. In 1964 he had an offer to co-star in the play Any Wednesday with actress Sandy Dennis. This opened the door to film work. His first role was in Lilith, with Warren Beatty in the leading role. In 1967 he appeared in an episode of the television series The Invaders entitled "The Spores". Another supporting role, Buck Barrow in 1967's Bonnie and Clyde,[12] earned him an Academy Award nomination as Best Supporting Actor. In 1968 he appeared in an episode of I Spy, in the role of "Hunter", in the episode "Happy Birthday... Everybody". That same year he starred in the CBS Playhouse episode "My Father and My Mother" and the dystopian television film Shadow on the Land.[21] In 1969 he played a ski coach in Downhill Racer and an astronaut in Marooned. Also that year, he played a member of a barnstorming skydiving team that entertained mostly at county fairs, a movie which also inspired many to pursue skydiving and has a cult-like status amongst skydivers as a result: The Gypsy Moths. He nearly accepted the role of Mike Brady for the TV series The Brady Bunch,[22] but his agent advised that he decline it in exchange for a more promising role, which he did.

1970s[]

Hackman was nominated for a second Best Supporting Actor Academy Award for his role in I Never Sang for My Father (1970). The next year, he won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance as New York City Detective Jimmy "Popeye" Doyle in The French Connection (1971), marking his graduation to leading-man status.[12]

After The French Connection, Hackman starred in ten films (not including his cameo in Young Frankenstein) over the next three years, making him the most prolific actor in Hollywood during that time frame. He followed The French Connection with leading roles in the disaster film The Poseidon Adventure (1972) and Francis Ford Coppola's The Conversation (1974), which was nominated for several Oscars.[12] That same year, Hackman appeared, in what would become one of his most famous comedic roles, as Harold the Blind Man in Young Frankenstein.[23]

He appeared as one of Teddy Roosevelt's former Rough Riders in the Western horse-race saga Bite the Bullet (1975). He reprised his Oscar-winning role as Doyle in the sequel French Connection II (1975), and was part of an all-star cast in the war film A Bridge Too Far (1977), playing Polish General Stanisław Sosabowski. Hackman showed a talent for both comedy and the "slow burn" as criminal mastermind Lex Luthor in Superman: The Movie (1978), a role he would reprise in its 1980 and 1987 sequels.

1980s[]

Gene is someone who is a very intuitive and instinctive actor...The brilliance of Gene Hackman is that he can look at a scene and he can cut through to what is necessary, and he does it with extraordinary economy—he's the quintessential movie actor. He's never showy ever, but he's always right on.

Alan Parker

director of Mississippi Burning (1988)[24]

Hackman alternated between leading and supporting roles during the 1980s, with prominent roles in Reds (1981)—directed by and starring Warren Beatty—Under Fire (1983), Hoosiers (1986) (which an American Film Institute poll in 2008 voted the fourth-greatest film of all time in the sports genre),[25] No Way Out (1987) and Mississippi Burning (1988), where he was nominated for a second Best Actor Oscar.[26] Between 1985 and 1988, he starred in nine films, making him the busiest actor, alongside Steve Guttenberg.[27]

1990s[]

Hackman appeared with Anne Archer in Narrow Margin (1990), a remake of the 1952 film The Narrow Margin. In 1992, he played the sadistic sheriff "Little" Bill Daggett in the Western Unforgiven directed by Clint Eastwood and written by David Webb Peoples. Hackman had pledged to avoid violent roles, but Eastwood convinced him to take the part, which earned him a second Oscar, this time for Best Supporting Actor. The film also won Best Picture.[12]

In 1993, he appeared in Geronimo: An American Legend as Brigadier General George Crook, and co-starred with Tom Cruise as a corrupt lawyer in The Firm, a legal thriller based on the John Grisham novel of the same name. Hackman would appear in a second film based on a John Grisham novel, playing a convict on death row in The Chamber (1996).

Other notable films Hackman appeared in during the 1990s include Wyatt Earp (1994) (as Nicholas Porter Earp, Wyatt Earp's father), The Quick and the Dead (1995) opposite Sharon Stone, Leonardo DiCaprio and Russell Crowe, and as submarine Captain Frank Ramsey alongside Denzel Washington in Crimson Tide (1995). Hackman played movie director Harry Zimm with John Travolta in the comedy-drama Get Shorty (1995). He reunited with Clint Eastwood in Absolute Power (1997), and co-starred with Will Smith in Enemy of the State (1998), his character reminiscent of the one he had portrayed in The Conversation.

In 1996, he took a comedic turn as conservative Senator Kevin Keeley in The Birdcage[28] with Robin Williams and Nathan Lane.

2000s[]

Hackman co-starred with Owen Wilson in Behind Enemy Lines (2001), and appeared in the David Mamet crime thriller Heist (2001),[29] as an aging professional thief of considerable skill who is forced into one final job. He also gained much critical acclaim playing against type as the head of an eccentric family in Wes Anderson's comedy film The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), for which he received the Golden Globe Award for Best Actor in a Motion Picture Musical or Comedy. In 2003, he also starred in another John Grisham legal drama, Runaway Jury, at long last getting to make a picture with his long-time friend Dustin Hoffman. In 2004, Hackman appeared alongside Ray Romano in the comedy Welcome to Mooseport, his final film acting role to date.[30]

Hackman was honored with the Cecil B. DeMille Award from the Golden Globe Awards for his "outstanding contribution to the entertainment field" in 2003.[31]

Retirement from acting[]

On July 7, 2004, Hackman gave a rare interview to Larry King, where he announced that he had no future film projects lined up and believed his acting career was over. In 2008, while promoting his third novel, he confirmed that he had retired from acting.[32] When asked during a GQ interview in 2011 if he would ever come out of retirement to do one more film, he said he might consider it "if I could do it in my own house, maybe, without them disturbing anything and just one or two people."[33] He briefly came out of retirement to narrate two documentaries related to the Marine Corps: The Unknown Flag Raiser of Iwo Jima (2016)[34] and We, The Marines (2017).[35]

Career as a novelist[]

Together with undersea archaeologist Daniel Lenihan, Hackman has written three historical fiction novels: Wake of the Perdido Star (1999),[36] a sea adventure of the 19th century; Justice for None (2004),[37] a Depression-era tale of murder; and Escape from Andersonville (2008) about a prison escape during the American Civil War.[38] His first solo effort, a story of love and revenge set in the Old West titled Payback at Morning Peak, was released in 2011.[39] A police thriller, Pursuit, followed in 2013.

In 2011, he appeared on the Fox Sports Radio show The Loose Cannons, where he discussed his career and his novels with Pat O'Brien, Steve Hartman, and Vic "The Brick" Jacobs.

Personal life[]

Hackman's first marriage was to Faye Maltese.[40] They had three children: Christopher Allen, Elizabeth Jean, and Leslie Anne Hackman.[41] The couple divorced in 1986 after three decades of marriage.[42] In 1991 he married classical pianist Betsy Arakawa;[43] they have a home in Santa Fe, New Mexico.[44]

In the late 1970s, Hackman competed in Sports Car Club of America races, driving an open-wheeled Formula Ford.[45][46] In 1983, he drove a Dan Gurney Team Toyota in the 24 Hours of Daytona Endurance Race.[47] He also won the Long Beach Grand Prix Celebrity Race.[48]

Hackman underwent an angioplasty in 1990.[49]

Hackman is a supporter of the Democratic Party, and was proud to be included on Nixon's Enemies List. However, he has spoken fondly of Republican president Ronald Reagan.[50]

He is an avid fan of the Jacksonville Jaguars and regularly attended Jaguars games as a guest of then head coach Jack Del Rio.[51][52] Their friendship goes back to Del Rio's playing days at the University of Southern California.[53]

In January 2012, the then 81-year-old Hackman was riding a bicycle in the Florida Keys when he was struck by a car.[54] He made a full recovery, and was still an active bicyclist as of 2021, at the age of 91.[55]

Theatre credits[]

- The Premise improv theatre at The Premise, on Bleecker Street, NYC (1960/61)

- Children From Their Games by Irwin Shaw at the Morosco Theatre (April 1963)

- A Rainy Day in Newark by Howard Teichmann at the Belasco Theatre (October 1963)

- Come to the Palace of Sin by Michael Shurtleff at the Lucille Lortel Theatre (1963)

- Any Wednesday by Muriel Resnik at the Music Box Theatre and the George Abbott Theatre (1964–1966)

- Poor Richard by Jean Kerr with Alan Bates and Shirley Knight at the Helen Hayes Theatre (1964–1965)[56]

- The Natural Look by Leonora Thuna at the Longacre Theatre (1967)

- Fragments and The Basement by Murray Schisgal at the Cherry Lane Theatre (1967)

- Death and the Maiden by Ariel Dorfman with Glenn Close and Richard Dreyfuss, directed by Mike Nichols, at the Brooks Atkinson Theatre (1992)

Filmography[]

Film[]

Television[]

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1961 | Tallahassee 7000 | Joe Lawson | Episode: "The Fugitive" |

| 1963 | Route 66 | Motorist | Episode: "Who Will Cheer My Bonny Bride?" |

| 1967 | The FBI | Herb Kenyon | Episode: "The Courier" |

| The Invaders | Tom Jessup | Episode: "The Spores" |

Accolades[]

Asteroid 55397 Hackman, discovered by Roy Tucker in 2001, was named in his honor.[57] The official naming citation was published by the Minor Planet Center on May 18, 2019 (M.P.C. 114954).[58]

Works or publications[]

- Hackman, Gene, and Daniel Lenihan. Wake of the Perdido Star. New York: Newmarket Press, 1999. ISBN 978-1-557-04398-6.

- Hackman, Gene, and Daniel Lenihan. Justice for None. New York: St. Martins Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-312-32425-4.

- Hackman, Gene, and Daniel Lenihan. Escape from Andersonville: A Novel of the Civil War. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-312-36373-4.

- Hackman, Gene. Payback at Morning Peak: A Novel of the American West. New York: Simon & Schuster Inc, 2011. ISBN 978-1-451-62356-7.

- Hackman, Gene. Pursuit. New York: Pocket Books, 2013. ISBN 978-1-451-62357-4.

References[]

- ^ His middle name is "Allen", according to the California Birth Index, 1905–1995. Center for Health Statistics, California Department of Health Services, Sacramento, California. At Ancestry.com

- ^ "Eugene Allen Hackman - California, Birth Index". FamilySearch. January 30, 1930. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ "Gene Allen Hackman - United States Census, 1940". FamilySearch. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ "Eugene A Hackman - United States Census, 1930". FamilySearch. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ "Gene Hackman Biography (1930–)". Filmreference.com. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Anna Lyda Elizabeth Gray - Canada, Births and Baptisms". FamilySearch. May 13, 1904. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ "Gene Hackman from Danville in 1940 Census District 92-22". archives.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Norman, Michael (March 19, 1989). "HOLLYWOOD'S UNCOMMON EVERYMAN". New York Times. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Leman, Kevin (2007). What Your Childhood Memories Say about You: And What You Can Do about It. Tyndale House Publishers, Inc. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-4143-1186-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "GENE HACKMAN LEAST LIKELY TO SUCCEED". Deseret News. Deseret News. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ "1945 Storm Lake High Yearbook". classmates.com. Retrieved July 28, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Stated on Inside the Actors Studio, 2001

- ^ "Hackman, Eugene, Cpl". www.marines.togetherweserved.com. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- ^ "Gene Hackman profile". Eonline.com. Archived from the original on October 29, 2008. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- ^ "Gene Hackman | Biography, Movies, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved April 11, 2020.

- ^ Lee, Luaine (May 8, 1986). "PASADENA PLAYHOUSE, A STAR CRUCIBLE, REOPENS". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ "Dustin Hoffman and Gene Hackman". Xfinity. Comcast. Archived from the original on April 16, 2011. Retrieved December 31, 2011.

- ^ Stevenson, Laura (September 5, 1977). "Robert Duvall, Hollywood's No. 1 Second Lead, Breaks for Starlight". People. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Meryman, Richard (March 2004). "Gene Hackman, Dustin Hoffman, and Robert Duvall: Three Friends who Went from Rags to Riches". Vanity Fair. Condé Nast. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ "VINTAGE MOVIES: "THE FRENCH CONNECTION"". Magnet. August 7, 2013. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ Roberts, Jerry (June 5, 2009). Encyclopedia of Television Film Directors. Scarecrow Press. p. 500. ISBN 9780810863781. Retrieved February 3, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ "You'll never watch 'The Brady Bunch' the same way again after reading these 12 facts". Me TV. June 9, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ "Weekend Top 10, Aug. 3, 2018". Champaign/Urbana News-Gazette. Champaign/Urbana News-Gazette. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ Gonthier, David F. and O'Brien, Timothy M. The Films of Alan Parker, 1976-2003, McFarland (2015) p. 167

- ^ "MAFFEI: 'Hoosiers' still a classic after 25 years". San Diego Union Tribune. San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- ^ "1989 Oscars". Oscars. Oscars. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- ^ Cohn, Lawrence (October 5, 1988). "Acting Jobs Steadiest Since Studio Era". Variety. p. 1.

- ^ "The Birdcage at 20". NY Daily News. NY Daily News. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- ^ "FILM REVIEW; Forget the Girl and Gold; Look for the Chemistry -". New York Times. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ "Cameron Diaz and other celebs who have retired from stage and screen". AZ Central. AZ Central. Retrieved August 18, 2018.

- ^ "Business Wire, November 14, 2002. Hollywood. 'Gene Hackman to Receive HFPA'S Cecil B. DeMille Award At 60th Annual Golden Globe Awards to be Telecast Live on NBC on Sunday, January 19, 2003'". Findarticles.com. November 14, 2002. Archived from the original on July 9, 2012. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ Blair, Iain (June 5, 2008). "Just a Minute With: Gene Hackman on his retirement". Reuters. Retrieved July 19, 2008.

- ^ Hainey, Michael (June 1, 2011). "Eighty-one Years. Seventy-nine Movies. Two Oscars. Not One Bad Performance". GQ. Retrieved February 25, 2017.

- ^ Smithsonian Channel.com: Sneak Peek: The Unknown Flag Raiser of Iwo Jima, archived from the original on September 13, 2017, retrieved October 31, 2018

- ^ Barber, James (December 20, 2018). "'Marine for Life' Gene Hackman Narrates the Story of the USMC". Military.com. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ "Hackman's, Bergen's talents shine on film, in books". Bouldercityreview. Bouldercityreview. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ "Unknown Flag Raiser of Iwo Jima': Gene Hackman narrates". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ Blair, Ian (June 5, 2008). Tourtellotte, Bob; Reaney, Patricia (eds.). "Just a Minute With: Gene Hackman on his retirement". Reuters. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- ^ Daniel, Douglass K. (July 30, 2011). "'Payback at Morning Peak': Actor Gene Hackman revisits the West — as a writer". Seattle Times. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ Ross, Shane (August 6, 2000). "The Gene genie works his magic off screen". Irish Independent. INM Website. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ^ Brady, James (December 30, 2001). "In Step with Gene Hackman". Parade. The Blade. Retrieved September 28, 2013.

- ^ Norman, Michael (March 19, 1989). "Hollywood's Uncommon Everyman". The New York Times. p. 6029. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ Lidz, Franz. "Gene Hackman's new novel - AARP The Magazine". AARP. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ "Police: Hackman knew homeless man he slapped in NM". The Associated Press, AP Regional State Report - New Mexico. November 1, 2012.

- ^ Finke, Nikki (March 13, 1998). "PLEASURES OF THE ROAD : TRACK STARS : Paul Newman, Gene Hackman, Perry King and Lorenzo Lamas rap on racing". LA Times. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ^ Siano, Joseph (October 23, 2002). "ON THE TRACK; Movie Stars as Racecar Drivers: What's Their Motivation?". The New York Times. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ^ Frankel, Andrew (January 2, 2016). "Actors with driving ambition". Telegraph. Retrieved August 24, 2018.

- ^ "Grand Prix of Long Beach 2016 Fan Guide" (PDF). Grand Prix of Long Beach. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ "Still the Tough Guy". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- ^ Chilton, Martin (January 26, 2020). "Gene Hackman: The tormented, brawling genius of film". The Independent. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ Parziale, James (April 13, 2013). "Most famous fan of every NFL team". MSN.com. p. 15. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ Parziale, James (October 20, 2016). "Most famous fan of every NFL team". Fox Sports. FOX. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ BART HUBBUCHThe Times-Union (November 29, 2005). "JAGUARS NOTEBOOK: Chatter angers Cardinals". Jacksonville.com. Archived from the original on January 4, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ "Gene Hackman struck by car while riding bike". CNN Entertainment. January 14, 2012. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- ^ https://twitter.com/jimlneibaur/status/1422211815023521793?s=21

- ^ "Star Rote for Gene Hackman". The New York Times. August 31, 1964. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ "55397 Hackman (2001 SY288)". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ "MPC/MPO/MPS Archive". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gene Hackman. |

- Gene Hackman at AllMovie

- Gene Hackman at IMDb

- Gene Hackman at the TCM Movie Database

- Gene Hackman at the Internet Broadway Database

- Gene Hackman at the Internet Off-Broadway Database

- 1930 births

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century American novelists

- 21st-century American male actors

- 21st-century American novelists

- Male actors from California

- American male film actors

- American male novelists

- American male stage actors

- American people of Canadian descent

- American people of English descent

- American people of Pennsylvania Dutch descent

- American people of German descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- Art Students League of New York alumni

- Best Actor Academy Award winners

- Best Actor BAFTA Award winners

- Best Drama Actor Golden Globe (film) winners

- Best Musical or Comedy Actor Golden Globe (film) winners

- Best Supporting Actor Academy Award winners

- Best Supporting Actor BAFTA Award winners

- Best Supporting Actor Golden Globe (film) winners

- Cecil B. DeMille Award Golden Globe winners

- Living people

- Male Western (genre) film actors

- Outstanding Performance by a Cast in a Motion Picture Screen Actors Guild Award winners

- People from Danville, Illinois

- Actors from San Bernardino, California

- Male actors from Santa Fe, New Mexico

- People from Storm Lake, Iowa

- Military personnel from Iowa

- Silver Bear for Best Actor winners

- Writers from Santa Fe, New Mexico

- United States Marines

- University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign College of Media alumni

- 20th-century American male writers

- 21st-century American male writers

- Novelists from California

- Novelists from New York (state)