Genocide recognition politics

Genocide recognition politics are efforts to have a certain event (re)interpreted as a "genocide" or officially designated as such.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] Such efforts may occur regardless of whether the event meets the definition of genocide laid out in the 1948 Genocide Convention.[8]

By country[]

Canada[]

As of June 2021, the government of Canada officially recognises eight genocides: the Holocaust (Second World War), the Armenian genocide (1915–1917), the Holodomor (1932–1933), the Rwandan genocide (1994), the Srebrenica massacre (1995), the Genocide of Yazidis by ISIL (2014), the Uyghur genocide (2014–present; recognised by Canada in February 2021), and the Rohingya genocide (2016–present). Some activists and scholars such as David Bruce MacDonald have argued that the Canadian government should also officially recognise various atrocities committed against the Indigenous peoples in Canada from the late 19th century until the mid-20th century as 'genocide', especially after the 2021 Canadian Indian residential schools gravesite discoveries.[9][10][11]

Germany[]

Canadian political scientist David Bruce MacDonald stated in June 2021 that it is rare for governments to recognise genocides committed by previous administrations of the same country, citing Germany as an example: it has officially recognised the Holocaust (committed by Nazi Germany during the Second World War), and in May 2021 Germany officially recognised the Herero and Namaqua genocide (committed by the German Empire in 1904–1908).[11]

Israel[]

On 21 November 2018, a bill tabled by opposition MP Ksenia Svetlova (ZU) to recognise the Islamic State's killing of Yazidis as a genocide was defeated in a 58 to 38 vote in the Knesset. The coalition parties motivated their rejection of the bill by saying that the United Nations had not yet recognised it as a genocide.[12]

Netherlands[]

In their 2017–2021 coalition agreement published on 10 October 2017, the four parties forming the Third Rutte cabinet stated the following policy: "For the Dutch government, rulings from international courts of justice or criminal courts, unambiguous conclusions from scientific research, and findings by the UN, are leading in the recognition of genocides. The Netherlands act in accordance with the obligations arising from the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. At the UN Security Council, the Netherlands are pro-active in combating ISIS and the prosecution of ISIS fighters."[13] On 22 February 2018, the Dutch House of Representatives formally recognised the Armenian genocide with 147 votes out of 150; only the three MPs of the Dutch Turks-dominated party DENK opposed recognition as a "too one-sided explanation of history".[14] Although the Dutch government stated it would not (yet) take a stand on whether it was a genocide, instead using the phrase "the Armenian genocide question", it agreed with MP Joël Voordewind's suggestion to send a government representative to attend Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day in Yerevan every 5 years "to show respect to all victims and survivors of all massacres against minorities", said Foreign Minister Sigrid Kaag.[14] On 9 February 2021, a large majority of the House supported a motion calling on the government to fully recognise the Armenian genocide and dropping the phrase "the Armenian genocide question"; the only parties who did not support the call were the VVD, and again DENK.[15] Inge Drost, spokesperson for the Federation Armenian Organisations Netherlands, stated in April 2021: "Every time recognition was brought up, it turned out to be a political bargaining tool. Then a country wanted get something out of Turkey, and threatened to recognise the Armenian genocide. Then eventually, it did not happen. It's a very sensitive issue for us."[16]

United Kingdom[]

The legal department of the British Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office has a long-standing policy, dating back to the 1948 passing of the Genocide Convention, of refusing to give a legal description to potential war crimes. For this reason, it has sought to dissuade any UK governmental institution from making claims about genocide. On 20 April 2016, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom unanimously supported a motion to declare that the treatment of Yazidis and Christians by the Islamic State amounted to genocide, to condemn it as such, and to refer the issue to the UN Security Council. It was almost unprecedented for British parliamentarians to collectively to declare war-time actions as genocide, because in doing so, Conservative MPs defied their fellow party members in the UK government. Foreign Office secretary Tobias Ellwood – who was jeered at and interrupted by MPs during his speech in the debate – stated that he personally believed genocide had taken place, but that it was not up to politicians to make that determination, but to the courts.[17]

United States[]

Between 1989 and 2019, the United States Department of State has formally recognised five genocides: in Bosnia (1993), Rwanda (1994), Iraq (1995), Darfur (2004), and areas under the control of ISIS (2016 and 2017).[18] Three other cases were considered, namely Burundi in the mid-1990s, Sudan's "Two Areas" in 2013, and Burma in 2018, but ultimately the process of recognition was not completed.[18] A March 2019 USHMM report by Buchwald & Keith stated: "No formal policy exists or has existed to guide how or when the US government decides whether genocide has occurred and whether to state its conclusion publicly."[18] However, there are two memoranda – the first written by Secretary of State Warren Christopher in May 1994 regarding Rwanda, and the second by Secretary of State Colin Powell in June 2004 regarding Darfur – that provide some insight into the decision-making process, and advise or authoritise U.S. government officials on what to do in genocide recognition questions.[18]

By event[]

Anfal campaign[]

| # | Name | Date of recognition | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21 November 2012 | [19] | |

| 3 | 1 March 2013 | [20] | |

| 4 | 13 June 2013 | [21] |

Armenian genocide[]

Assyrian genocide (Sayfo)[]

Atrocities in the Congo Free State[]

... It was indeed a holocaust before Hitler's Holocaust. ... What happened in the heart of Africa was genocidal in scope long before that now familiar term, genocide, was ever coined.

Historian Robert Weisbord (2003)[41]

The significant number of deaths under the Free State regime has led some scholars to relate the atrocities to later genocides, though understanding of the losses under the colonial administration's rule as the result of harsh economic exploitation rather than a policy of deliberate extermination has led others to dispute the comparison;[42] there is an open debate as to whether the atrocities constitute genocide.[43] According to the United Nations' 1948 definition of the term "genocide", a genocide must be "acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group".[44] Sociologist Rhoda Howard-Hassmann stated that because the Congolese were not killed in a systematic fashion according to this criterion, "technically speaking, this was not genocide even in a legally retroactive sense."[45] Hochschild and political scientist rejected allegations of genocide in the Free State because there was no evidence of a policy of deliberate extermination or the desire to eliminate any specific population groups,[46][47] though the latter added that nevertheless there was "a death toll of Holocaust proportions."[45]

... no reputable historian of the Congo has made charges of genocide; a forced labor system, although it may be equally deadly, is different.

Historian Adam Hochschild (2005)[48]

It is generally agreed by historians that extermination was never the policy of the Free State. According to historian David Van Reybrouck, "It would be absurd ... to speak of an act of 'genocide' or a 'holocaust'; genocide implies the conscious, planned annihilation of a specific population, and that was never the intention here, or the result ... But it was definitely a hecatomb, a slaughter on a staggering scale that was not intentional, but could have been recognised much earlier as the collateral damage of a perfidious, rapacious policy of exploitation".[49] Historian Barbara Emerson stated, "Leopold did not start genocide. He was greedy for money and chose not to interest himself when things got out of control."[50] According to Hochschild, "while not a case of genocide, in the strict sense", the atrocities in the Congo were "one of the most appalling slaughters known to have been brought about by human agency".[51][a]

Historians have argued that comparisons drawn in the press by some between the death toll of the Free State atrocities and the Holocaust during World War II have been responsible for creating undue confusion over the issue of terminology.[54][55] In one incident, the Japanese newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun used the word "genocide" in the title of a 2005 article by Hochschild. Hochschild himself criticised the title as "misleading" and stated that it had been chosen "without my knowledge". Similar criticism was echoed by historian .[54][49]

Allegations of genocide in the Free State have become common over time.[56] Political scientist Martin Ewans wrote, "Leopold's African regime became a byword for exploitation and genocide."[57] According to historian , "Those who easily apply the term genocide to Leopold's regime seem to do so purely on the basis of its obvious horror and the massive numbers of people who may have perished."[56] Robert Weisbord argued that there does not have to be intent to exterminate all members of a population in a genocide.[55] He posited that "an endeavor to eliminate a portion of a people would qualify as genocide" according to the UN standards and asserted that the Free State did as much.[45] Jeanne Haskin, Yaa-Lengi Meema Ngemi, and David Olusoga also referred to the atrocities as a genocide.[45][58] In an unpublished manuscript from the 1950s, Lemkin, coiner of the term "genocide", asserted the occurrence of "an unambiguous genocide" in the Free State, attributing most of the population decline to the repressive actions of colonial troops.[42] In 2005, an early day motion before the British House of Commons, introduced by Andrew Dismore, called for the recognition of the Congo Free State's atrocities as a "colonial genocide" and called on the Belgian government to issue a formal apology. It was supported by 48 MPs.[59]

In 1999 Hochschild published King Leopold's Ghost, a book detailing the atrocities committed during the Free State existence. The book became a bestseller in Belgium, but aroused criticism from former Belgian colonialists and some academics as exaggerating the extent of the atrocities and population decline.[50] Around the 50th anniversary of the Congo's independence from Belgium in 2010, numerous Belgian writers published content about the Congo. Historian Idesbald Goddeeris criticised these works—including Van Reybrouk's Congo: A History—for taking a softened stance on the atrocities committed in the Congolese Free State, saying "They acknowledge the dark period of the Congo Free State, but...they emphasize that the number of victims was unknown and that the terror was concentrated in particular regions."[60]

The term "Congolese genocide" is often used in an unrelated sense to refer to the mass murder and rape committed in the eastern Congo in the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide (and the ensuing Second Congo War) between 1998 and 2003.[61][62]Black War[]

The near-destruction of Tasmania's Aboriginal population has been described as an act of genocide by historians including Robert Hughes, James Boyce, Lyndall Ryan and Tom Lawson.[63][64][65][66] The author of the concept of genocide, Raphael Lemkin, considered Tasmania the site of one of the world's clear cases of genocide[67] and Hughes has described the loss of Aboriginal Tasmanians as "the only true genocide in English colonial history".[63]

Boyce has claimed that the April 1828 "Proclamation Separating the Aborigines from the White Inhabitants" sanctioned force against Aboriginal people "for no other reason than that they were Aboriginal" and described the decision to remove all Aboriginal Tasmanians after 1832—by which time they had given up their fight against white colonists—as an extreme policy position. He concluded: "The colonial government from 1832 to 1838 ethnically cleansed the western half of Van Diemen's Land and then callously left the exiled people to their fate."[68] As early as 1852 John West's History of Tasmania portrayed the obliteration of Tasmania's Aboriginal people as an example of "systematic massacre"[69] and in the 1979 High Court case of Coe v Commonwealth of Australia, judge Lionel Murphy observed that Aboriginal people did not give up their land peacefully and that they were killed or forcibly removed from their land "in what amounted to attempted (and in Tasmania almost complete) genocide".[70]

Historian Henry Reynolds says there was a widespread call from settlers during the frontier wars for the "extirpation" or "extermination" of the Aboriginal people.[71] But he has contended that the British government acted as a source of restraint on settlers' actions. Reynolds says there is no evidence the British government deliberately planned the wholesale destruction of indigenous Tasmanians—a November 1830 letter to Arthur by Sir George Murray warned that the extinction of the race would leave "an indelible stain upon the character of the British Government"[72]—and therefore what eventuated does not meet the definition of genocide codified in the 1948 United Nations convention. He says Arthur was determined to defeat the Aboriginal people and take their land, but believes there is little evidence he had aims beyond that objective and wished to destroy the Tasmanian race.[73]

Clements accepts Reynolds' argument but also exonerates the colonists themselves of the charge of genocide. He says that unlike genocidal determinations by Nazis against Jews in World War II, Hutus against Tutsis in Rwanda and Ottomans against Armenians in present-day Turkey, which were carried out for ideological reasons, Tasmanian settlers participated in violence largely out of revenge and self-preservation. He adds: "Even those who were motivated by sex or morbid thrillseeking lacked any ideological impetus to exterminate the natives." He also argues that while genocides are inflicted on defeated, captive or otherwise vulnerable minorities, Tasmanian natives appeared as a "capable and terrifying enemy" to colonists and were killed in the context of a war in which both sides killed noncombatants.[74]

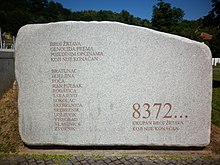

Lawson, in a critique of Reynolds' stand, argues that genocide was the inevitable outcome of a set of British policies to colonise Van Diemen's Land.[75] He says the British government endorsed the use of partitioning and "absolute force" against Tasmanians, approved Robinson's "Friendly Mission" and colluded in transforming that mission into a campaign of ethnic cleansing from 1832. He says that once on Flinders Island, indigenous peoples were taught to farm land like Europeans and worship God like Europeans and concludes: "The campaign of transformation enacted on Flinders Island amounted to cultural genocide."[76]Bosnian genocide[]

The term "Bosnian genocide" refers to either the Srebrenica massacre, or the wider crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing campaign throughout areas controlled by the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS)[77] during the Bosnian War of 1992–1995.[78] The events in Srebrenica in 1995 included the killing of more than 8,000 Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) men and boys, as well as the mass expulsion of another 25,000–30,000 Bosniak civilians by VRS units under the command of General Ratko Mladić.[79][80]

In the 1990s, several authorities asserted that ethnic cleansing as carried out by elements of the Bosnian Serb army was genocide.[81] These included a resolution by the United Nations General Assembly and three convictions for genocide in German courts (the convictions were based upon a wider interpretation of genocide than that used by international courts).[82] In 2005, the United States Congress passed a resolution declaring that "the Serbian policies of aggression and ethnic cleansing meet the terms defining genocide."[83]

The Srebrenica massacre was found to be an act of genocide by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY), a finding upheld by the International Court of Justice (ICJ).[84] On 24 March 2016, former Bosnian Serb leader and the first president of the Republika Srpska, Radovan Karadžić, was found guilty of genocide in Srebrenica, war crimes, and crimes against humanity and sentenced to 40 years in prison. In 2019 an appeals court increased his sentence to life imprisonment.[85] The ICTY found the acts to have satisfied the requirements for "guilty acts" of genocide, and that, "some physical perpetrators held the intent to physically destroy the protected groups of Bosnian Muslims and Croats".[86]

California genocide[]

Circassian genocide[]

Former Russian President Boris Yeltsin's May 1994 statement admitted that resistance to the tsarist forces was legitimate, but he did not recognize "the guilt of the tsarist government for the genocide."[89] In 1997 and 1998, the leaders of Kabardino-Balkaria and of Adygea sent appeals to the Duma to reconsider the situation and to issue an apology; to date, there has been no response from Moscow. In October 2006, the Adygeyan public organizations of Russia, Turkey, Israel, Jordan, Syria, the United States, Belgium, Canada, and Germany have sent the president of the European Parliament a letter with the request to recognize the genocide against Adygean (Circassian) people.[90]

On 5 July 2005, the , an organization that unites representatives of the various Circassian peoples in the Russian Federation, has called on Moscow first to acknowledge and then to apologize for tsarist policies that Circassians say constituted a genocide.[91] Their appeal pointed out that "according to the official tsarist documents more than 400,000 Circassians were killed, 497,000 were forced to flee abroad to Turkey, and only 80,000 were left alive in their native area."[89] The Russian parliament (Duma) rejected the petition in 2006 in a statement that acknowledged past actions of the Soviet and previous regimes while referring to in overcoming multiple contemporary problems and issues in the Caucasus through cooperation.[91] There is concern by the Russian government that acknowledging the events as genocide would entail possible claims of financial compensation in addition to efforts toward repatriating diaspora Circassians back to Circassia.[91]

On 21 May 2011, the Parliament of Georgia passed a resolution, stating that "pre-planned" mass killings of Circassians by Imperial Russia, accompanied by "deliberate famine and epidemics", should be recognized as "genocide" and those deported during those events from their homeland, should be recognized as "refugees". Georgia, which has poor relations with Russia, has made outreach efforts to North Caucasian ethnic groups since the 2008 Russo-Georgian War.[92] Following a consultation with academics, human rights activists and Circassian diaspora groups and parliamentary discussions in Tbilisi in 2010 and 2011, Georgia became the first country to use the word "genocide" to refer to the events.[92][93][94][95] On 20 May 2011 the parliament of the Republic of Georgia declared in its resolution[96] that the mass annihilation of the Cherkess (Adyghe) people during the Russian-Caucasian war and thereafter constituted genocide as defined in the Hague Convention of 1907 and the UN Convention of 1948. The next year, on the same day of 21 May, a monument was erected in Anaklia, Georgia, to commemorate the suffering of the Circassians.[97]

In Russia, a presidential commission has been set up to try and deny the Circassian genocide, with respect to the events of the 1860s.[98]

On 1 December 2015, in the Great Union Day (the national day of Romania), a large number of Circassian representatives sent a request to the Romanian Government asking it to recognize the Circassian genocide. The letter was specifically sent to the President (Klaus Iohannis), the Prime Minister (Dacian Cioloș), the President of the Senate (Călin Popescu-Tăriceanu) and the President of the Chamber of Deputies (Valeriu Zgonea). The document included 239 signatures and was written in Arabic, English, Romanian and Turkish. Similar requests had already been sent earlier by Circassian representatives to Estonia, Lithuania, Moldova, Poland and Ukraine.[99][100] In the case of Moldova, the request was sent on 27 August of the same year (2015), on the Moldovan Independence Day, to the President (Nicolae Timofti), the Prime Minister (Valeriu Streleț) and the President of the Parliament (Andrian Candu). The request was also redacted in Arabic, English, Romanian and Turkish languages and included 192 signatures.[101][102]Deportation of the Chechens and Ingush[]

The forced relocation, slaughter, and conditions during and after transfer have been described as on act of genocide by various scholars as well as the European Parliament[103] on the basis of the IV Hague Convention of 1907 and the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide of the U.N. General Assembly (adopted in 1948), including French historian and expert on communist studies Nicolas Werth,[104] German historian Philipp Ther,[105] Professor Anthony James Joes,[106] American journalist Eric Margolis,[107] Canadian political scientist Adam Jones,[108] professor of Islamic History at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth Brian Glyn Williams,[109] scholars Michael Fredholm[110] and Fanny E. Bryan.[111] Raphael Lemkin, a lawyer of Polish-Jewish descent who initiated the Genocide Convention, assumed that genocide was perpetrated in the context of the mass deportation of the Chechens, Ingush, Volga Germans, Crimean Tatars, Kalmyks and Karachay.[112] German investigative journalist Lutz Kleveman compared the deportation to a "slow genocide".[113] In this case this was acknowledged by the European Parliament as an act of genocide in 2004:[103]

...Believes that the deportation of the entire Chechen people to Central Asia on 23 February 1944 on the orders of Stalin constitutes an act of genocide within the meaning of the Fourth Hague Convention of 1907 and the Convention for the Prevention and Repression of the Crime of Genocide adopted by the UN General Assembly on 9 December 1948.[114]

Experts of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum cited the events of 1944 for a reason of placing Chechnya on their genocide watch list for its potential for genocide.[115] The separatist government of Chechnya also recognized it as genocide.[116] Members of the Chechen diaspora and their supporters promote February 23 as World Chechnya Day to commemorate the victims.[117]

The Chechens, along with the Ingush, Karachai and Balkars, are represented in the Confederation of Repressed Peoples (CRP), an organization that covers the former Soviet Union and aims to support and rehabilitate the rights of the deported peoples.[118]Draining of the Mesopotamian Marshes[]

The draining of the Mesopotamian Marshes occurred in Iraq and to a smaller degree in Iran between the 1950s and 1990s to clear large areas of the marshes in the Tigris-Euphrates river system. Formerly covering an area of around 20,000 km2 (7,700 sq mi), the main sub-marshes, the Hawizeh, Central, and Hammar marshes and all three were drained at different times for different reasons.

The draining of the marshes was undertaken primarily for political ends, namely to force the Marsh Arabs out of the area through water diversion tactics and to punish them for their role in the 1991 uprising against Saddam Hussein's government.[119] However, the government's stated reasoning was to reclaim land for agriculture and exterminate a breeding ground for mosquitoes.[120] The displacement of more than 200,000 of the Ma'dan and the associated state-sponsored campaign of violence against them has led the United States and others to describe the draining of the marshes as ecocide or ethnic cleansing.[121][122][123]

The draining of the Mesopotamian Marshes has been described by the United Nations as a "tragic human and environmental catastrophe" on par with the deforestation of the Amazon rainforest[124] and by other observers as one of the worst environmental disasters of the 20th century.[125]Genocide of Yazidis by ISIL[]

Many international organisations, governments and parliaments, as well as groups have classified ISIL's treatment of the Yazidis as genocide, and condemned it as such. The Genocide of Yazidis has been officially recognized by several bodies of the United Nations[126][127] and the European Parliament.[128] Many states have recognized it as well, for example the Armenian parliament,[129] the Australian parliament,[130][better source needed] the British parliament,[131] the Canadian parliament,[132] the Scottish Parliament,[133] and the United States parliament.[134] Multiple individual human rights activists such as Nazand Begikhani and Dr. Widad Akrawi have also advocated for this view.[135][136]

United Nations:

United Nations:

- In a March 2015 report, the persecution of the Yazidi people was qualified as a genocide by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCR). The organization cited the numerous atrocities such as forced religious conversion and sexual slavery as being parts of an overall malicious campaign.[137][138]

- In August 2017, the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic of the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) stated that 'ISIL committed the crime of genocide by seeking to destroy the Yazidis through killings, sexual slavery, enslavement, torture, forcible displacement, the transfer of children and measures intended to prohibit the birth of Yazidi children.' It added that the genocide was ongoing, and stating that the international community still must recognize the detrimental effects of the genocide. The Commission wrote that, while some countries may choose to overlook the idea of the genocide, the atrocities need to be understood and the international community needs to bring the killings to an end.[139]

- In 2018, the Security Council team enforced the idea of a new accountability team that would collect evidence of the international crimes committed by the Islamic State. However, the international community has not been in full support of this idea, because it can sometimes oversee the crimes that other armed groups are involved in.[140]

- On 10 May 2021, the United Nations Investigative Team to Promote Accountability for Crimes Committed by Da'esh/ISIL (UNITAD) determined that ISIL's actions in Iraq constituted genocide.[141][142][143]

Council of Europe: On 27 January 2016, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe adopted a resolution stating: "...individuals who act in the name of the terrorist entity which calls itself "Islamic State" (Daesh) (...) have perpetrated acts of genocide and other serious crimes punishable under international law. States should act on the presumption that Daesh commits genocide and should be aware that this entails action under the 1948 United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide." However, it did not identify victims.[144]

Council of Europe: On 27 January 2016, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe adopted a resolution stating: "...individuals who act in the name of the terrorist entity which calls itself "Islamic State" (Daesh) (...) have perpetrated acts of genocide and other serious crimes punishable under international law. States should act on the presumption that Daesh commits genocide and should be aware that this entails action under the 1948 United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide." However, it did not identify victims.[144]

European Union: On 4 February 2016, the European Parliament unanimously passed a resolution to recognise 'that the so-called 'ISIS/Daesh' is committing genocide against Christians and Yazidis, and other religious and ethnic minorities, who do not agree with the so-called 'ISIS/Daesh' interpretation of Islam, and that this therefore entails action under the 1948 United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.'[128][145] Additionally, it called for those who intentionally committed atrocities for ethnic or religious reasons to be brought to justice for violating international law, and committing crimes against humanity, and genocide.[128][145]

European Union: On 4 February 2016, the European Parliament unanimously passed a resolution to recognise 'that the so-called 'ISIS/Daesh' is committing genocide against Christians and Yazidis, and other religious and ethnic minorities, who do not agree with the so-called 'ISIS/Daesh' interpretation of Islam, and that this therefore entails action under the 1948 United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.'[128][145] Additionally, it called for those who intentionally committed atrocities for ethnic or religious reasons to be brought to justice for violating international law, and committing crimes against humanity, and genocide.[128][145]

United States: The United States Department of State has formally recognised the Yazidi genocide in areas under the control of ISIS in 2016 and 2017.[146] On 14 March 2016, the United States House of Representatives voted unanimously 393-0 that violent actions performed against Yazidis, Christians, Shia and other groups by ISIL were acts of genocide. Days later on 17 March 2016, United States Secretary of State John Kerry declared that the violence initiated by ISIL against the Yazidis and others amounted to genocide.[134]

United States: The United States Department of State has formally recognised the Yazidi genocide in areas under the control of ISIS in 2016 and 2017.[146] On 14 March 2016, the United States House of Representatives voted unanimously 393-0 that violent actions performed against Yazidis, Christians, Shia and other groups by ISIL were acts of genocide. Days later on 17 March 2016, United States Secretary of State John Kerry declared that the violence initiated by ISIL against the Yazidis and others amounted to genocide.[134]

United Kingdom: On 20 April 2016, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom unanimously supported a motion to declare that the treatment of Yazidis and Christians by the Islamic State amounted to genocide, to condemn it as such, and to refer the issue to the UN Security Council. In doing so, Conservative MPs defied their fellow party members in the UK government, who had tried to dissuade Tory MPs from making such a statement, because of the Foreign Office legal department's long-standing policy (dating back to the 1948 passing of the Genocide Convention) of refusing to give a legal description to potential war crimes. Foreign Office secretary Tobias Ellwood – who was jeered at and interrupted by MPs during his speech in the debate – stated that he personally believed genocide had taken place, but that it was not up to politicians to make that determination, but to the courts.[131]

United Kingdom: On 20 April 2016, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom unanimously supported a motion to declare that the treatment of Yazidis and Christians by the Islamic State amounted to genocide, to condemn it as such, and to refer the issue to the UN Security Council. In doing so, Conservative MPs defied their fellow party members in the UK government, who had tried to dissuade Tory MPs from making such a statement, because of the Foreign Office legal department's long-standing policy (dating back to the 1948 passing of the Genocide Convention) of refusing to give a legal description to potential war crimes. Foreign Office secretary Tobias Ellwood – who was jeered at and interrupted by MPs during his speech in the debate – stated that he personally believed genocide had taken place, but that it was not up to politicians to make that determination, but to the courts.[131]

Canada: On 25 October 2016, the House of Commons of Canada unanimously supported a motion tabled by MP Michelle Rempel Garner (CPC) to recognise that ISIS was committing genocide against the Yazidi people, to acknowledge that ISIS still kept many Yazidi women and girls captive as sex slaves, to support and take action on a recent UN commission report, and provide asylum to Yazidi women and girls within 120 days.[132]

Canada: On 25 October 2016, the House of Commons of Canada unanimously supported a motion tabled by MP Michelle Rempel Garner (CPC) to recognise that ISIS was committing genocide against the Yazidi people, to acknowledge that ISIS still kept many Yazidi women and girls captive as sex slaves, to support and take action on a recent UN commission report, and provide asylum to Yazidi women and girls within 120 days.[132]

France: On 6 December 2016, the French Senate unanimously approved a resolution stating that acts committed by the Islamic State against "the Christian and Yazidi populations, other minorities and civilians" were "war crimes", "crimes against humanity", and constituted a "genocide." It also invited the government to "use all legal channels" to have these crimes recognised, and the perpetrators tried.[147] The National Assembly adopted a similar resolution two days later (originally tabled on 25 May 2016 by Yves Fromion of The Republicans), with the Socialist, Ecologist and Republican group abstaining and the other groups approving.[148][149]

France: On 6 December 2016, the French Senate unanimously approved a resolution stating that acts committed by the Islamic State against "the Christian and Yazidi populations, other minorities and civilians" were "war crimes", "crimes against humanity", and constituted a "genocide." It also invited the government to "use all legal channels" to have these crimes recognised, and the perpetrators tried.[147] The National Assembly adopted a similar resolution two days later (originally tabled on 25 May 2016 by Yves Fromion of The Republicans), with the Socialist, Ecologist and Republican group abstaining and the other groups approving.[148][149]

Scotland: On 23 March 2017, the Scottish Parliament adopted a motion stating: '[The Scottish Parliament] recognises and condemns the genocide perpetrated against the Yezidi people by Daesh [ISIS]; acknowledges the great human suffering and loss that have been inflicted by bigotry, brutality and religious intolerance, [and] further acknowledges and condemns the crimes perpetrated by Daesh against Muslims, Christians, Arabs, Kurds and all of the religious and ethnic communities of Iraq and Syria; welcomes the actions of the US Congress, the European Parliament, the French Senate, the UN and others in formally recognising the genocide'.[133][150]

Scotland: On 23 March 2017, the Scottish Parliament adopted a motion stating: '[The Scottish Parliament] recognises and condemns the genocide perpetrated against the Yezidi people by Daesh [ISIS]; acknowledges the great human suffering and loss that have been inflicted by bigotry, brutality and religious intolerance, [and] further acknowledges and condemns the crimes perpetrated by Daesh against Muslims, Christians, Arabs, Kurds and all of the religious and ethnic communities of Iraq and Syria; welcomes the actions of the US Congress, the European Parliament, the French Senate, the UN and others in formally recognising the genocide'.[133][150]

Armenia: In January 2018, the Armenian parliament recognised and condemned the 2014 genocide of Yazidis by the Islamic State, and called on the international community to conduct an international investigation into the events.[151]

Armenia: In January 2018, the Armenian parliament recognised and condemned the 2014 genocide of Yazidis by the Islamic State, and called on the international community to conduct an international investigation into the events.[151]

Israel: On 21 November 2018, a bill tabled by opposition MP Ksenia Svetlova (ZU) to recognise the Islamic State's killing of Yazidis as a genocide was defeated in a 58 to 38 vote in the Knesset. The coalition parties motivated their rejection of the bill by saying that the United Nations had not yet recognised it as a genocide.[152]

Israel: On 21 November 2018, a bill tabled by opposition MP Ksenia Svetlova (ZU) to recognise the Islamic State's killing of Yazidis as a genocide was defeated in a 58 to 38 vote in the Knesset. The coalition parties motivated their rejection of the bill by saying that the United Nations had not yet recognised it as a genocide.[152]

Iraq: On 1 March 2021, the Iraq parliament passed the Yazidi [Female] Survivors Bill which provides assistance to survivors and "determines the atrocities perpetrated by Daesh against the Yazidis, Turkmen, Christians and Shabaks to be genocide and crimes against humanity."[153] The law provides compensation, measures for rehabilitation and reintegration, pensions, provision of land, housing, and education, and a quota in public sector employment.[154] On 10 May 2021, the United Nations Investigative Team to Promote Accountability for Crimes Committed by Da'esh/ISIL (UNITAD) determined that ISIL's actions in Iraq constituted genocide.[141]

Iraq: On 1 March 2021, the Iraq parliament passed the Yazidi [Female] Survivors Bill which provides assistance to survivors and "determines the atrocities perpetrated by Daesh against the Yazidis, Turkmen, Christians and Shabaks to be genocide and crimes against humanity."[153] The law provides compensation, measures for rehabilitation and reintegration, pensions, provision of land, housing, and education, and a quota in public sector employment.[154] On 10 May 2021, the United Nations Investigative Team to Promote Accountability for Crimes Committed by Da'esh/ISIL (UNITAD) determined that ISIL's actions in Iraq constituted genocide.[141]

Belgium: On 30 June 2021, the Foreign Relations Commission of the Belgian Chamber of Representatives unanimously approved a resolution by opposition representatives Georges Dallemagne (cdH) and (N-VA) to recognise ISIL's August 2014 massacre of thousands of Yazidi men and enslavement of thousands of Yazidi women and children as genocide. The resolution, which would likely also pass with overwhelming approval in the Chamber itself, called on the Belgian government to increase its efforts to support victims, and prosecute perpetrators (either at the International Criminal Court, or at a new ad hoc tribunal).[155] On 17 July 2021, the Belgian parliament unanimously voted to recognize the suffering of the Yazidis at the hands of the Islamic State (ISIS) in 2014 as a genocide.[156]

Belgium: On 30 June 2021, the Foreign Relations Commission of the Belgian Chamber of Representatives unanimously approved a resolution by opposition representatives Georges Dallemagne (cdH) and (N-VA) to recognise ISIL's August 2014 massacre of thousands of Yazidi men and enslavement of thousands of Yazidi women and children as genocide. The resolution, which would likely also pass with overwhelming approval in the Chamber itself, called on the Belgian government to increase its efforts to support victims, and prosecute perpetrators (either at the International Criminal Court, or at a new ad hoc tribunal).[155] On 17 July 2021, the Belgian parliament unanimously voted to recognize the suffering of the Yazidis at the hands of the Islamic State (ISIS) in 2014 as a genocide.[156]

Greek genocide[]

Following an initiative of MPs of the so-called "patriotic" wing of the ruling PASOK party's parliamentary group and like-minded MPs of conservative New Democracy,[158] the Greek Parliament passed two laws on the fate of the Ottoman Greeks; the first in 1994 and the second in 1998. The decrees were published in the Greek Government Gazette on 8 March 1994 and 13 October 1998 respectively. The 1994 decree affirmed the genocide in the Pontus region of Asia Minor and designated 19 May (the day Mustafa Kemal landed in Samsun in 1919) a day of commemoration,[159] (called Pontian Greek Genocide Remembrance Day[160]) while the 1998 decree affirmed the genocide of Greeks in Asia Minor as a whole and designated 14 September a day of commemoration.[161] These laws were signed by the President of Greece but were not immediately ratified after political interventions. After leftist newspaper I Avgi initiated a campaign against the application of this law, the subject became subject of a political debate. The president of the left-ecologist Synaspismos party Nikos Konstantopoulos and historian Angelos Elefantis,[162] known for his books on the history of Greek communism, were two of the major figures of the political left who expressed their opposition to the decree. However, the non-parliamentary left-wing nationalist[163] intellectual and author George Karabelias bitterly criticized Elefantis and others opposing the recognition of genocide and called them "revisionist historians", accusing the Greek mainstream left of a "distorted ideological evolution". He said that for the Greek left 19 May is a "day of amnesia".[164]

In the late 2000s the Communist Party of Greece adopted the term "Genocide of the Pontic (Greeks)" (Γενοκτονία Ποντίων) in its official newspaper Rizospastis and participates in memorial events.[165][166][167]

The Republic of Cyprus has also officially called the events "Greek Genocide in Pontus of Asia Minor".[168]

In response to the 1998 law, the Turkish government released a statement which claimed that describing the events as genocide was "without any historical basis". "We condemn and protest this resolution" a Turkish Foreign Ministry statement said. "With this resolution the Greek Parliament, which in fact has to apologize to the Turkish people for the large-scale destruction and massacres Greece perpetrated in Anatolia, not only sustains the traditional Greek policy of distorting history, but it also displays that the expansionist Greek mentality is still alive," the statement added.[169]

On 11 March 2010, Sweden's Riksdag passed a motion recognising "as an act of genocide the killing of Armenians, Assyrians/Syriacs/Chaldeans and Pontic Greeks in 1915".[170]

On 14 May 2013, the government of New South Wales was submitted a genocide recognition motion by Fred Nile of the Christian Democratic Party, which was later passed making it the fourth political entity to recognise the genocide.[171]

In March 2015, the National Assembly of Armenia unanimously adopted a resolution recognizing both the Greek and Assyrian genocides.[172]

In April 2015, the States General of the Netherlands and the Austrian Parliament passed resolutions recognizing the Greek and Assyrian genocides.[173][174]Holocaust[]

There is a virtually unanimous consensus in the international community that the Holocaust was committed primarily by Nazi Germany against the Jews and other minorities in the early 1940s, due to overwhelming evidence, although there are some differences in names and definitions, periodisation, scope (for example, whether the 1941–44 Romani genocide/Porajmos should be recognised as part of the Holocaust,[175] or as a separate genocide committed simultaneously with the Holocaust[176]), attributed responsibility, and motivation. There is a wide range of Holocaust memorial days, memorials and museums, and education policies. Unlike with other genocides, much of the politics surrounding the Holocaust are not about formally recognising it in political statements (since there is already a strong consensus), but focus on its importance, which aspects should be emphasised, how to prevent it or similar genocides from happening again, how to combat Holocaust denial, and whether it should be illegal to deny it. Some regimes, politicians or organisations may occasionally deny or downplay the Holocaust for various reasons, such as antisemitism, in opposition to the State of Israel, or for comparisons with other genocides deemed more or similarly important.

Holodomor[]

The following sovereign states have recognized the Holodomor as an act of genocide:[177][178] Argentina, Australia, Canada, Colombia, Ecuador, Estonia, Georgia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Mexico, Paraguay, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Ukraine, and the Vatican. (The United States Congress and Senate passed resolutions of recognition, but the executive branch has not formally stated this.) The United States does not yet officially recognize the Holodomor as genocide.[179] The Baltic Assembly—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania collectively—has also condemned the Holodomor as genocide. See Holodomor genocide question for more on the topic.

Many countries have signed declarations in statements at the UNGA affirming that the Holodomor was as a "national tragedy of the Ukrainian people" caused by the "cruel actions and policies of the totalitarian regime".[b] Similar statements were passed as resolutions by the following international organizations:[c] the European Parliament[d], the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE),[e] the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE),[180][181] and the United Nations Organization for Education, Science and Culture (UNESCO).[b]

The following countries have signed declarations for the United Nations on the Holodomor:[f][g][184][185][186] Albania,[h] Argentina,[188][189][190] Australia,[191][192][193][194][h] Austria,[h] Azerbaijan,[h] Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada,[195][196] Chile, Colombia,[197][198] Czechia[199] Croatia, Denmark, Ecuador,[200][201] Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, Moldova, Monaco, Montenegro, Paraguay, Peru, Poland,[202][203] Portugal, Slovakia,[204][205] Spain, Ukraine, United States.[206][207] The Vatican City also recognized the Holodomor as genocide.[208]Khojaly massacre[]

Historian Donald Bloxham states that it is inaccurate to see the Khojaly massacre as a genocide, stating that it is a "misleading deployment of the term in pursuit of nationalist goals".[211]

Romani genocide[]

The German government paid war reparations to Jewish survivors of the Holocaust, but not to the Romani. There were "never any consultations at Nuremberg or any other international conference as to whether the Sinti and Roma were entitled like the Jews to reparations."[212] The Interior Ministry of Wuerttemberg argued that "Gypsies [were] persecuted under the Nazis not for any racial reason but because of an asocial and criminal record".[213] When on trial for his leadership of Einsatzgruppen in the USSR, Otto Ohlendorf cited the massacres of Romanis during the Thirty Years War as a historical precedent.[214]

West Germany recognised the genocide of the Roma in 1982,[215] and since then the Porajmos has been increasingly recognized as a genocide committed simultaneously with the Shoah.[216] The American historian wrote several articles arguing that the Porajmos deserved recognition as part of the Holocaust.[217] In Switzerland, a committee of experts investigated the policy of the Swiss government during the Porajmos.[218]

Formal recognition and commemoration of the Roma persecution by the Nazis have been difficult in practical terms due to the lack of significant collective memory and documentation of the Porajmos among the Roma. This results from both of their tradition of oral history and illiteracy, heightened by widespread poverty and continuing discrimination that has forced some Roma out of state schools. One UNESCO report of Roma in Romania showed that only 40% of Roma children are enrolled in primary school, compared to the national average of 93%.[219] Of those enrolled, only 30% of Roma children go on to complete primary school. In a 2011 investigation of the state of the Roma in Europe today, Ben Judah, a Policy Fellow with the European Council on Foreign Relations, traveled to Romania.

Nico Fortuna, a sociologist and Roma activist, explained the distinction between Jewish collective memory of the Shoah and the Roma experience:

Ian Hancock has also observed a reluctance among Roma to acknowledge their victimization by the Third Reich. The Roma "are traditionally not disposed to keeping alive the terrible memories from their history—nostalgia is a luxury for others".[221] The effects of the illiteracy, the lack of social institutions, and the rampant discrimination faced by Roma in Europe today have produced a people who, according to Fortuna, lack a "national consciousness ... and historical memory of the Holocaust because there is no Roma elite."[220]There is a difference between the Jewish and Roma deportees ... The Jews were shocked and can remember the year, date and time it happened. The Roma shrugged it off. They said, "Of course I was deported. I'm Roma; these things happen to a Roma." The Roma mentality is different from the Jewish mentality. For example, a Roma came to me and asked, "Why do you care so much about these deportations? Your family was not deported." I went, "I care as a Roma" and the guy said back, "I do not care because my family were brave, proud Roma that were not deported."

For the Jews it was total and everyone knew this—from bankers to pawnbrokers. For the Roma it was selective and not comprehensive. The Roma were only exterminated in a few parts of Europe such as Poland, the Netherlands, Germany and France. In Romania and much of the Balkans, only nomadic Roma and social outcast Roma were deported. This matters and influences the Roma mentality.[220]

Uyghur genocide[]

In June 2019, the China Tribunal, an independent judicial investigation into forced organ transplantation in China concluded that crimes against humanity had been committed beyond reasonable doubt against China's Uyghur Muslim and Falun Gong populations.[222][223]

The use of the full "genocide" term did not gain traction until after the publication of a report by Adrian Zenz for the Jamestown Foundation and an article by the Associated Press in late June 2020 on forced sterilizations.[224]

In July 2020, Zenz said an interview with National Public Radio (NPR) that he had previously argued that the actions of the Chinese government are a cultural genocide, not a "literal genocide", but that one of the five criteria from the Genocide Convention was satisfied by more recent developments concerning the suppression of birth rates so "we do need to probably call it a genocide".[225] The same month, the last colonial governor of British Hong Kong, Chris Patten, said that the "birth control campaign" was "arguably something that comes within the terms of the UN views on sorts of genocide" and the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China demanded an independent UN investigation. At roughly the same time, U.S. senators Kirsten Gillibrand and Kamala Harris urged the Trump administration to investigate the allegations.[226]

Although the People's Republic of China (PRC) is not a member of the International Criminal Court, on 6 July 2020 the East Turkistan Government-in-Exile and the East Turkistan National Awakening Movement filed a complaint with the ICC calling for it to investigate PRC officials for crimes against Uyghurs including allegations of genocide.[227][228][229] The ICC responded in December 2020 and "asked for more evidence before it will be willing to open an investigation into claims of genocide against Uighur people by China, but has said it will keep the file open for such further evidence to be submitted."[230]

An August 2020 Quartz article reported that some scholars hesitate to label the human rights abuses in Xinjiang as a "full-blown genocide", preferring the term "cultural genocide", but that increasingly many experts were calling them "crimes against humanity" or "genocide".[227] Also in August 2020 the spokesperson for Joe Biden’s presidential campaign described China's actions as genocide.[231]

In October 2020, the U.S. Senate introduced a bipartisan resolution designating the human rights abuses perpetrated by the Chinese government against the Uyghur people and other ethnic minorities in Xinjiang as genocide.[232] Around the same time, the House of Commons of Canada issued a statement that its Subcommittee on International Human Rights of the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development was persuaded that the Chinese Communist Party's actions in Xinjiang constitute genocide as laid out in the Genocide Convention.[233] The 2020 annual report by the Congressional-Executive Commission on China referred to the Chinese government's treatment of Uyghurs as "crimes against humanity and possibly genocide."[234][235]

The Asia-Pacific Centre for the Responsibility to Protect at the University of Queensland concluded in November that evidence of atrocities in Xinjiang "likely meets the requirements of the following crimes against humanity: persecution, imprisonment, enforced disappearance, torture, forced sterilisation, and enslavement" and that "It is arguable that genocidal acts have occurred in Xinjiang, in particular acts of imposing measures to prevent births and forcible transfers."[236] In December, lawyers David Matas and wrote in Toronto Star that "One distressing present day example [of genocide] is the atrocities faced by the Uighur population in Xinjiang, China."[237]

In January 2021, U.S. secretary of state Mike Pompeo announced that the U.S. government would be officially designating the crimes against the Uyghurs and other Turkic and Muslim people living in China as a genocide.[238] This declaration, which came in the final hours of the Trump administration, had not been made earlier due to a worry that it could disrupt trade talks between the US and China. On the allegations of crimes against humanity Pompeo asserted that "These crimes are ongoing and include: the arbitrary imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty of more than one million civilians, forced sterilization, torture of a large number of those arbitrarily detained, forced labor and the imposition of draconian restrictions on freedom of religion or belief, freedom of expression and freedom of movement."[239]

However, there was internal disagreement within the administration with the Office of the Legal Advisor concluding that although the situation in Xinjiang amounts to crimes against humanity, there was insufficient evidence to prove genocide.[240] Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying responded to the designation by calling Pompeo a "doomsday clown", and dismissing the allegations of genocide as "wastepaper" and "pseudo-propositions and a malicious farce concocted by individual anti-China and anti-Communist forces represented by Pompeo".[241] On 19 January 2021, incoming U.S. president Joe Biden's secretary of state nominee Antony Blinken was asked during his confirmation hearings whether he agreed with Pompeo's conclusion that the CCP has committed genocide against the Uyghurs, he contended "That would be my judgment as well."[242] During her confirmation hearings Joe Biden's nominee to be the US ambassador to the United Nations Linda Thomas-Greenfield stated that she believed what was currently happening in Xinjiang was a genocide, adding "I lived through and experienced and witnessed a genocide in Rwanda."[243]

In January 2021, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum stated that, "[t]here is a reasonable basis to believe that the government of China is committing crimes against humanity."[244][245]

When asked about the situation by a reporter, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson stated that "what's happening to the Uyghurs is utterly abhorrent" but that "the attribution of genocide is a judicial matter".[241] Chinese state media ran op-eds and reports disputing the use of the term “genocide".[231]

The US designation was followed by Canada's House of Commons and the Dutch parliament each passing a non-binding motion in February 2021 to recognize China's actions as genocide.[246][247]

In February 2021, a report released by the Essex Court Chambers concluded that "there is a very credible case that acts carried out by the Chinese government against the Uighur people in Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region amount to crimes against humanity and the crime of genocide, and describes how the minority group has been subject to "enslavement, torture, rape, enforced sterilisation and persecution." "Victims have been "forced to remain in stress positions for an extended period of time, beaten, deprived of food, shackled and blindfolded”, it said. The legal team state they have seen “prolific credible evidence” of sterilisation procedures carried out on women, including forced abortions, saying they “clearly constitute a form of genocidal conduct”.[248]

According to a March 2021 Newlines Institute report that was written by over 50 worldwide experts on China, genocide, and international law,[249][250] the Chinese government breached every article in the Genocide Convention, writing that “simply put, China's long-established, publicly and repeatedly declared, specifically targeted, systematically implemented, and fully resourced policy and practice toward the Uyghur group is inseparable from 'the intent to destroy in whole or in part' the Uyghur group as such."[251][252][253] The report, published by the Newlines Institute for Strategy and Policy, said there were credible reports of mass deaths under the mass internment drive, while Uighur leaders were selectively sentenced to death or sentenced to long-term imprisonment. “Uyghurs are suffering from systematic torture and cruel, inhumane, and degrading treatment, including rape, sexual abuse, and public humiliation, both inside and outside the camps,” the report stated. The report argued that these policies are directly orchestrated by the highest levels of state, including Xi and the top officials of the Chinese Communist Party in Xinjiang.[254] It also reported that the Chinese government gave explicit orders to "eradicate tumours", "wipe them out completely", "destroy them root and branch", “round up everyone", and "show absolutely no mercy", in regards to Uyghurs,[254][250] and that camp guards reportedly follow orders to uphold the system in place until ‘Kazakhs, Uyghurs, and other Muslim nationalities, would disappear...until all Muslim nationalities would be extinct’.”[255] According to the report "Internment camps contain designated “interrogation rooms,” where Uyghur detainees are subjected to consistent and brutal torture methods, including beatings with metal prods, electric shocks, and whips."[256]

In June 2021, the Canadian Anthropology Society issued a statement on Xinjiang in which the organization stated, "expert testimony and witnessing, and irrefutable evidence from the Chinese Government's own satellite imagery, documents, and eyewitness reports, overwhelmingly confirms the scale of the genocide."[257]See also[]

- Historical negationism

- Holocaust denial

- Rohingya genocide case

Notes[]

- ^ As a comparison, Hochschild labelled the German extermination of the Herero in South-West Africa (1904–1907) a genocide because of its defined, systematic and intentional nature.[52][53]

- ^ Jump up to: a b See the United Nations for a list of resolutions with references.

- ^ See United Nations section for details and references.

- ^ See European Parliament section for text and references for European Parliament resolution of 23 October 2008 on the commemoration of the Holodomor, the Ukraine artificial famine.

- ^ See Council of Europe for details and references.

- ^ For details on recognition, see National recognition.

- ^ For a list of nations which were co-author sponsors of the UN Declaration on 85th anniversary of Holodomor, see [182][183]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Nation has signed the United Nations Declaration on the Eighty-Fifth Anniversary of the Holodomor of 1932-1933 in Ukraine.[187]

References[]

- ^ Mutlu-Numansen, Sofia; Ossewaarde, Marinus (2019). "A Struggle for Genocide Recognition: How the Aramean, Assyrian, and Chaldean Diasporas Link Past and Present". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 33 (3): 412–428. doi:10.1093/hgs/dcz045.

- ^ de Waal, Thomas (2015). "The G-Word: The Armenian Massacre and the Politics of Genocide". Foreign Affairs. 94 (1): 136–148. ISSN 0015-7120.

- ^ Beachler, D. (2011). The Genocide Debate: Politicians, Academics, and Victims. Springer. ISBN 978-0-230-33763-3.

- ^ Baser, Bahar; Toivanen, Mari (2017). "The politics of genocide recognition: Kurdish nation-building and commemoration in the post-Saddam era". Journal of Genocide Research. 19 (3): 404–426. doi:10.1080/14623528.2017.1338644. hdl:10138/325889.

- ^ Koinova, Maria (2019). "Diaspora coalition-building for genocide recognition: Armenians, Assyrians and Kurds". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 42 (11): 1890–1910. doi:10.1080/01419870.2019.1572908.

- ^ Sjöberg, Erik (2016). The Making of the Greek Genocide: Contested Memories of the Ottoman Greek Catastrophe. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-78533-326-2.

- ^ Catic, Maja (2015). "Circassians and the Politics of Genocide Recognition". Europe-Asia Studies. 67 (10): 1685–1708. doi:10.1080/09668136.2015.1102202.

- ^ Finkel, Evgeny (2010). "In Search of Lost Genocide: Historical Policy and International Politics in Post-1989 Eastern Europe". Global Society. 24 (1): 51–70. doi:10.1080/13600820903432027.

- ^ David MacDonald (4 June 2021). "Canada's hypocrisy: Recognizing genocide except its own against Indigenous peoples". The Conversation. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Matthew Kupfer (28 June 2021). "Indigenous people ask Canadians to 'put their pride aside' and reflect this Canada Day". CBC News. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Maan Alhmidi (5 June 2021). "Experts say Trudeau's acknowledgment of Indigenous genocide could have legal impacts". Global News. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ "Israel votes against formally recognizing Yazidi massacres by IS as genocide". i24 News. 21 November 2018. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ "Vertrouwen in de toekomst. Regeerakkoord 2017 – 2021 VVD, CDA, D66 en ChristenUnie" (PDF). tweedekamer.nl (in Dutch). Dutch House of Representatives. 10 October 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Tweede Kamer erkent Armeense genocide". RTL Nieuws (in Dutch). 22 February 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ ANP/Het Parool (9 February 2021). "Kamer roept regering op volmondig Armeense genocide te erkennen". Het Parool (in Dutch). Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "Armeniërs in Nederland: erkenning VS van Armeense genocide is 'pleister op de wonde'". NOS (in Dutch). 24 April 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Patrick Wintour (20 April 2016). "MPs unanimously declare Yazidis and Christians victims of Isis genocide". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Todd F. Buchwald (March 2019). "By Any Other Name. How, When, and Why the US Government Has Made Genocide Determinations" (PDF). United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "Norwegian Government recognises Saddam Hussein's genocide – Justice4Genocide calls on the British Government to do the same". 21 November 2012. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "British parliament unanimously recognises Kurdish genocide". 1 March 2013. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "South Korea recognizes Kurdish genocide". 13 June 2013. Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "Historic Debate Secures Parliamentary Recognition of the Kurdish Genocide". Huffingtonpost.co.uk. March 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ^ Academic consensus:

- Bloxham, Donald (2003). "Determinants of the Armenian Genocide". Looking Backward, Moving Forward. Routledge. pp. 23–50. doi:10.4324/9780203786994-3. ISBN 978-0-203-78699-4.

Despite growing scholarly consensus on the fact of the Armenian Genocide...

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (2009). "Truth in Telling: Reconciling Realities in the Genocide of the Ottoman Armenians". The American Historical Review. 114 (4): 930–946 [935]. doi:10.1086/ahr.114.4.930.

Overwhelmingly, since 2000, publications by non-Armenian academic historians, political scientists, and sociologists... have seen 1915 as one of the classic cases of ethnic cleansing and genocide. And, even more significantly, they have been joined by a number of scholars in Turkey or of Turkish ancestry...

- Göçek, Fatma Müge (2015). Denial of Violence: Ottoman Past, Turkish Present and Collective Violence Against the Armenians, 1789–2009. Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-19-933420-9.

The Western scholarly community is almost in full agreement that what happened to the forcefully deported Armenian subjects of the Ottoman Empire in 1915 was genocide...

- Smith, Roger W. (2015). "Introduction: The Ottoman Genocides of Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks". Genocide Studies International. 9 (1): 5. doi:10.3138/gsi.9.1.01. S2CID 154145301.

Virtually all American scholars recognize the [Armenian] genocide...

- Laycock, Jo (2016). "The great catastrophe". Patterns of Prejudice. 50 (3): 311–313. doi:10.1080/0031322X.2016.1195548. S2CID 147933878.

... important developments in the historical research on the genocide over the last fifteen years... have left no room for doubt that the treatment of the Ottoman Armenians constituted genocide according to the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide.

- Kasbarian, Sossie; Öktem, Kerem (2016). "One hundred years later: the personal, the political and the historical in four new books on the Armenian Genocide". Caucasus Survey. 4 (1): 92–104. doi:10.1080/23761199.2015.1129787. S2CID 155453676.

... the denialist position has been largely discredited in the international academy. Recent scholarship has overwhelmingly validated the Armenian Genocide...

- "Taner Akçam: Türkiye'nin, soykırım konusunda her bakımdan izole olduğunu söyleyebiliriz". CivilNet (in Turkish). 9 July 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- Bloxham, Donald (2003). "Determinants of the Armenian Genocide". Looking Backward, Moving Forward. Routledge. pp. 23–50. doi:10.4324/9780203786994-3. ISBN 978-0-203-78699-4.

- ^ Loytomaki, Stiina (2014). Law and the Politics of Memory: Confronting the Past. Routledge. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-136-00736-1.

To date, more than 20 countries in the world have officially recognized the events as genocide and most historians and genocide scholars accept this view.

- ^ Frey, Rebecca Joyce (2009). Genocide and international justice. New York: Facts On File. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-8160-7310-8.

- ^ Öktem, Emre (2011). "Turkey: Successor or Continuing State of the Ottoman Empire?". Leiden Journal of International Law. Cambridge University Press. 24 (3): 561–583. doi:10.1017/S0922156511000252. S2CID 145773201.

- ^ Gaunt 2015, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Gaunt, Atto & Barthoma 2017, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Yacoub 2016, p. 212.

- ^ Sjöberg 2016, pp. 202–203.

- ^ Sjöberg 2016, p. 215.

- ^ "Dutch Parliament Recognizes Assyrian, Greek and Armenian Genocide". Assyrian International News Agency. 10 April 2015.

- ^ "Austrian Parliament Recognizes Armenian, Assyrian, Greek Genocide". Assyrian International News Agency. 22 April 2015.

- ^ Abraham, Miryam A. (6 June 2016). "German Recognition of Armenian, Assyrian Genocide: History and Politics". Assyrian International News Agency.

- ^ "Syria Passes Resolution Condemning Turkish Genocide of Assyrians, Armenians". Assyrian International News Agency. 13 February 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ "Syrian Parliament Adopts Resolution Recognizing the Armenian Genocide". Massis Post. 13 February 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ "Assyrian Genocide Recognition in the United States". Assyrian Policy Institute. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ Gaunt, Atto & Barthoma 2017, p. 8.

- ^ Atto 2016, p. 184.

- ^ Sjöberg 2016, p. 197.

- ^ Weisbord 2003.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stapleton 2017, p. 87.

- ^ Gerdziunas, Benas (17 October 2017). "Belgium's genocidal colonial legacy haunts the country's future". The Independent. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Hochschild 1999, p. 255.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Stapleton 2017, p. 88.

- ^ Hochschild 1999, p. 225.

- ^ Nzongola-Ntalaja 2007, p. 22.

- ^ New York Review of Books 2005.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Van Reybrouck 2014, p. 95.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bates, Stephen (13 May 1999). "The hidden holocaust". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Ascherson 1999, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Hochschild 1999, pp. 281–2.

- ^ Simon 2007, p. 76.

- ^ Jump up to: a b New York Review of Books 2006.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vanthemsche 2012, p. 24.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stapleton 2017, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Ewans 2017, Introduction.

- ^ "Is this the end for colonial-era statues?". The Guardian. 19 June 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ Early day motion 2251.

- ^ Goddeeris 2015, p. 437.

- ^ Drumond 2011.

- ^ World Without Genocide 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hughes 1987, p. 120

- ^ Boyce 2010, p. 296

- ^ Ryan 2012, p. xix, 215

- ^ Lawson 2014, pp. xvii, 2, 20

- ^ Reynolds 2001, p. 50

- ^ Boyce 2010, pp. 264, 296

- ^ Lawson 2014, p. 8

- ^ Reynolds 2001, p. 29

- ^ Reynolds 2001, pp. 52–54

- ^ Reynolds 2001, p. 59

- ^ Lawson 2014, pp. 15, 78, 85

- ^ Clements 2014, pp. 56–58

- ^ Lawson 2014, p. 14

- ^ Lawson 2014, pp. 51, 205

- ^ A Witness to Genocide: The 1993 Pulitzer Prize-Winning Dispatches on the "Ethnic Cleansing" of Bosnia, Roy Gutman

- ^ John Richard Thackrah (2008). The Routledge companion to military conflict since 1945, Routledge Companions Series, Taylor & Francis, 2008, ISBN 0-415-36354-3, ISBN 978-0-415-36354-9. pp. 81–82: "Bosnian genocide can mean either the genocide committed by the Serb forces in Srebrenica in 1995 or the ethnic cleansing during the 1992–95 Bosnian War".

- ^ ICTY; "Address by ICTY President Theodor Meron, at Potocari Memorial Cemetery" The Hague, 23 June 2004 ICTY.org

- ^ ICTY; "Krstic judgement" UNHCR.org Archived 18 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jorgic v. Germany (Judgment), ECHR (12 July 2007). §§ 36, 47, 111.

- ^ Jorgic v. Germany (Judgment), ECHR (12 July 2007). §§ 47, 107, 108.

- ^ A resolution expressing the sense of the Senate regarding the massacre at Srebrenica in July 1995, 109th Congress (2005–2006), [S.RES.134]. Archived on 7 January 2016.

- ^ Jorgic v. Germany (Judgment), ECHR (12 July 2007). §§ 47, 112.

- ^ Simons, Marlise (20 March 2019). "Radovan Karadzic Sentenced to Life for Bosnian War Crimes". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ ICTY; "Karadzic indictment. Paragraph 19" ICTY.org

- ^ Cowan, Jill (19 June 2019). "'It's Called Genocide': Newsom Apologizes to the State's Native Americans". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ "Newsom apologizes for California's history of violence against Native Americans". Los Angeles Times. 18 June 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Paul Goble "Circassians demand Russian apology for 19th century genocide", Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty 15 July 2005, Volume 8, Number 23

- ^ Circassia: Adygs Ask European Parliament to Recognize Genocide

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Richmond 2008, p. 172.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Georgia Says Russia Committed Genocide in 19th Century. The New York Times. 20 May 2011

- ^ Hildebrandt, Amber (14 August 2012). "Russia's Sochi Olympics awakens Circassian anger". CBC News. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ Georgia Recognizes ‘Circassian Genocide’ Archived 18 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Civil Georgia. 20 May 2011

- ^ Recognizes Russian 'Genocide' Of Ethnic Circassians[permanent dead link]. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 20 May 2011

- ^ Грузия признала геноцид черкесов в царской России // Сайт «Лента.Ру» (lenta.ru), 20 May 2011.

- ^ "Georgian Diaspora – Calendar".

- ^ Richmond, Walter. The Circassian Genocide. p. 2.

- ^ "Черкесские активисты направили в Румынию просьбу признать геноцид черкесов Россией". Natpress (in Russian). 1 December 2015.

- ^ "A requisition is sent to Romania for recognizing the Circassian genocide". cherkessia.net. 1 December 2015.

- ^ "Черкесская общественность обратилась за признанием геноцида их предков к Молдове". Natpress (in Russian). 3 September 2015.

- ^ "A requisition is sent to Moldova for recognizing the Circassian genocide". cherkessia.net. 31 August 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Chechnya: European Parliament recognises the genocide of the Chechen People in 1944". Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. February 27, 2004. Archived from the original on June 4, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- ^ Werth 2008, p. 413.

- ^ Ther 2014, p. 118.

- ^ Joes 2010, p. 357.

- ^ Margolis 2008, p. 277.

- ^ Jones 2016, p. 203.

- ^ Williams 2015, p. 67.

- ^ Fredholm 2000, p. 315.

- ^ Bryan 1984, p. 99.

- ^ Courtois 2010, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Kleveman 2002, p. 87.

- ^ "Texts adopted: Final edition EU-Russia relations". Brussels: European Parliament. February 26, 2004. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- ^ "Speaker Series – The 60th Annniversary of the 1944 Chechen and Ingush Deportation: History, Legacies, Current Crisis". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. March 12, 2004. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ^ Tishkov 2004, p. 30.

- ^ Antoine Blua (February 23, 1944). "Kazakhstan: Chechens Mark 60th Anniversary Of Deportation". Radio Free Europe. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- ^ Cornell 2001, p. 241.

- ^ The Iraqi Government Assault on the Marsh Arabs (PDF) (Report). Human Rights Watch. January 2003. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ "Marsh Arabs". ICE Case Studies. January 2001. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ "The Marsh Arabs of Iraq: Hussein's Lesser Known Victims". United States Institute of Peace. 25 November 2002.

- ^ Nadeem A Kazmi, Sayyid (2000). "The Marshlands of Southern Iraq: A Very Humanitarian Dilemma" (PDF). III Jornadas de Medio Oriente. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ Priestley, Cara (2021). ""We Won't Survive in a City. The Marshes are Our Life": An Analysis of Ecologically Induced Genocide in the Iraqi Marshes". Journal of Genocide Research. 23 (2): 279–301. doi:10.1080/14623528.2020.1792615.

- ^ Partow, Hassan (13 August 2001). "UN ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME RELEASES REPORT ON DEMISE OF MESOPOTAMIAN MARSHLANDS" (Press release). Nairobi/Stockholm: United Nations. UN Environment Programme. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ Hopkin, Michael (21 February 2005). "Reflooding bodes well for Iraqi marshes". News@nature. doi:10.1038/news050221-1. ISSN 1744-7933.

- ^ "HCDH | UN Commission of Inquiry on Syria: ISIS is committing genocide against the Yazidis". www.ohchr.org. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- ^ "OHCHR | Statement by the Commission of Inquiry on Syria on the second anniversary of 3 August 2014 attack by ISIS of the Yazidis". www.ohchr.org. Archived from the original on 5 October 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Jack Moore (4 February 2016). "European Parliament recognizes ISIS killings of religious minorities as genocide". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ "Armenian Parliament recognizes Yazidi genocide". armenpress.am. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ "The pain of hearing: Australia's parliament recognises Yazidi genocide". www.lowyinstitute.org. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Patrick Wintour (20 April 2016). "MPs unanimously declare Yazidis and Christians victims of Isis genocide". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kathleen Harris (25 October 2016). "'Above politics': MPs vote unanimously to bring Yazidi refugees to Canada in 4 months". CBC News. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Scottish Parliament recognizes genocide against the Yezidi people". ARA News. 25 March 2017. Archived from the original on 19 May 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Labott, Elise (17 March 2016). "U.S. to declare genocide in Iraq and Syria". CNN. Archived from the original on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- ^ "Dr Widad Akrawi Interviewed at RojNews: How should the international community classify the systematic massacre of the Yezidi civilians in Sinjar by IS jihadists that included taking Yezidi girls as sex slaves". Archived from the original on 28 October 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ^ "Quick Links". CNN. Archived from the original on 15 July 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ "UN accuses the "Islamic State" in the genocide of the Yazidis" (in Russian). BBC Russian Service/BBC. 19 March 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ "UN: ISIS May Have Committed Genocide Against Yazidis". Huffington Post. 19 March 2015. Archived from the original on 16 August 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ "ISIL's 'genocide' against Yazidis is ongoing, UN rights panel says, calling for international action". United Nations. 3 August 2017. Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- ^ Schaack, Beth Van (2018). "The Iraq Investigative Team and Prospects for Justice for the Yazidi Genocide". Journal of International Criminal Justice. 16: 113–139. doi:10.1093/jicj/mqy002.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "ISIL crimes against Yazidis constitute genocide, UN investigation team finds". UN News. United Nations. 10 May 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ^ "ISIL committed genocide against Yazidis: UN investigation". Al Jazeera. 11 May 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ Isabel Bolle (12 May 2021). "VN-experts: IS is schuldig aan genocide op yezidi's". Trouw (in Dutch). Retrieved 6 July 2021.