Gothic language

| Gothic | |

|---|---|

| Region | Oium, Dacia, Pannonia, Dalmatia, Italy, Gallia Narbonensis, Gallia Aquitania, Hispania, Crimea, North Caucasus. |

| Era | attested 3rd–10th century; related dialects survived until 18th century in Crimea |

| Dialects | |

| Gothic alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | got |

| ISO 639-3 | got |

| Glottolog | goth1244 |

| Linguasphere | 52-ADA |

Gothic is an extinct East Germanic language that was spoken by the Goths. It is known primarily from the Codex Argenteus, a 6th-century copy of a 4th-century Bible translation, and is the only East Germanic language with a sizeable text corpus. All others, including Burgundian and Vandalic, are known, if at all, only from proper names that survived in historical accounts, and from loanwords in other languages such as Portuguese, Spanish, and French.

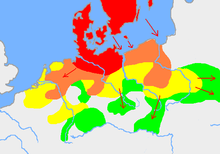

As a Germanic language, Gothic is a part of the Indo-European language family. It is the earliest Germanic language that is attested in any sizable texts, but it lacks any modern descendants. The oldest documents in Gothic date back to the fourth century. The language was in decline by the mid-sixth century, partly because of the military defeat of the Goths at the hands of the Franks, the elimination of the Goths in Italy, and geographic isolation (in Spain, the Gothic language lost its last and probably already declining function as a church language when the Visigoths converted to Catholicism in 589).[1] The language survived as a domestic language in the Iberian peninsula (modern-day Spain and Portugal) as late as the eighth century. Gothic-seeming terms are found in manuscripts subsequent to this date, but these may or may not belong to the same language. In particular, a language known as Crimean Gothic survived in the lower Danube area and in isolated mountain regions in Crimea. Lacking certain sound changes characteristic of Gothic, however, Crimean Gothic cannot be a lineal descendant of Bible Gothic.[2]

The existence of such early attested texts makes it a language of considerable interest in comparative linguistics.

History and evidence[]

Only a few documents in Gothic survive, not enough to completely reconstruct the language. Most Gothic-language sources are translations or glosses of other languages (namely, Greek), so foreign linguistic elements most certainly influenced the texts. These are the primary sources:

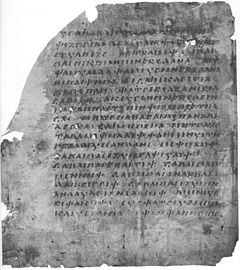

- The largest body of surviving documentation consists of various codices, mostly from the sixth century, copying the Bible translation that was commissioned by the Arian bishop Ulfilas (Wulfila, 311–382), leader of a community of Visigothic Christians in the Roman province of Moesia (modern-day Serbia, Bulgaria/Romania). He commissioned a translation of the Greek Bible into the Gothic language, of which roughly three-quarters of the New Testament and some fragments of the Old Testament have survived. The translations, performed by several scholars, are collected in the following codices:

- Codex Argenteus (Uppsala), including the Speyer fragment: 188 leaves

- The best-preserved Gothic manuscript and dating from the sixth century, it was preserved and transmitted by northern Ostrogoths in modern-day Italy. It contains a large portion of the four gospels. Since it is a translation from Greek, the language of the Codex Argenteus is replete with borrowed Greek words and Greek usages. The syntax in particular is often copied directly from the Greek.

- Codex Ambrosianus (Milan) and the (Turin): Five parts, totaling 193 leaves

- It contains scattered passages from the New Testament (including parts of the gospels and the Epistles), of the Old Testament (Nehemiah), and some commentaries known as Skeireins. The text likely had been somewhat modified by copyists.

- Codex Gissensis (Gießen): One leaf with fragments of Luke 23–24 (apparently a Gothic-Latin diglot) was found in an excavation in Arsinoë in Egypt in 1907 and was destroyed by water damage in 1945, after copies had already been made by researchers.

- Codex Carolinus (Wolfenbüttel): Four leaves, fragments of Romans 11–15 (a Gothic-Latin diglot).

- Codex Vaticanus Latinus 5750 (Vatican City): Three leaves, pages 57–58, 59–60, and 61–62 of the Skeireins. This is a fragment of Codex Ambrosianus E.

- Gothica Bononiensia (also known as the Codex Bononiensis), a recently discovered (2009) palimpsest fragment of two folios with what appears to be a sermon, containing besides non-biblical text a number of direct Bible quotes and allusions, both from previously attested parts of the Gothic Bible (the text is clearly taken from Ulfilas' translation) and previously unattested ones (e.g., Psalms, Genesis).[3]

- Fragmenta Pannonica (also known as the Hács-Béndekpuszta fragments or Tabella Hungarica), which consist of fragments of a 1 mm thick lead plate with remnants of verses from the Gospels.

- A scattering of old documents: two deeds (the Naples and Arezzo deeds, on papyri), alphabets (in the Gothica Vindobonensia and the Gothica Parisina), a calendar (in the Codex Ambrosianus A), glosses found in a number of manuscripts and a few runic inscriptions (between three and 13) that are known or suspected to be Gothic: some scholars believe that these inscriptions are not at all Gothic.[4] Several names in an Indian inscription were thought to be possibly Gothic by Krause.[5] Furthermore, late ninth-century Christian inscriptions using the Gothic alphabet, not runes, and copying or mimicking biblical Gothic orthography, have been found at Mangup in Crimea.[6]

- A small dictionary of more than 80 words and an untranslated song, compiled by the Fleming Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq, the Habsburg ambassador to the court of the Ottoman Empire in Istanbul from 1555 to 1562, who was curious to find out about the language and by arrangement met two speakers of Crimean Gothic and listed the terms in his compilation Turkish Letters: dating from nearly a millennium after Ulfilas, these terms are not representative of his language. Busbecq's material contains many puzzles and enigmas and is difficult to interpret in the light of comparative Germanic linguistics.[why?][citation needed]

Reports of the discovery of other parts of Ulfilas' Bible have not been substantiated. in 1968 claimed to have found in England twelve leaves of a palimpsest containing parts of the Gospel of Matthew.

Only fragments of the Gothic translation of the Bible have been preserved. The translation was apparently done in the Balkans region by people in close contact with Greek Christian culture. The Gothic Bible apparently was used by the Visigoths in southern France until the loss of Visigothic France at the start of the 6th century[7] and in Visigothic Iberia until about 700, and perhaps for a time in Italy, the Balkans, and Ukraine. In the latter country at Mangup, ninth-century inscriptions have been found of a prayer in the Gothic alphabet using biblical Gothic orthography.[6] In exterminating Arianism, many texts in Gothic were probably overwritten as palimpsests or collected and burned. Apart from biblical texts, the only substantial Gothic document that still exists and the only lengthy text known to have been composed originally in the Gothic language, is the Skeireins, a few pages of commentary on the Gospel of John.[citation needed]

Very few secondary sources make reference to the Gothic language after about 800. In De incrementis ecclesiae Christianae (840–842), Walafrid Strabo, a Frankish monk who lived in Swabia, speaks of a group of monks, who reported that even now certain peoples in Scythia (Dobruja), especially around Tomis spoke a sermo Theotiscus ('Germanic language'), the language of the Gothic translation of the Bible, and they used such a liturgy.[8]

In evaluating medieval texts that mention the Goths, many writers used the word Goths to mean any Germanic people in eastern Europe (such as the Varangians), many of whom certainly did not use the Gothic language as known from the Gothic Bible. Some writers even referred to Slavic-speaking people as Goths. However, it is clear from Ulfilas' translation that despite some puzzles the language belongs with the Germanic language group, not with Slavic.

The relationship between the language of the Crimean Goths and Ulfilas's Gothic is less clear. The few fragments of Crimean Gothic from the 16th century show significant differences from the language of the Gothic Bible although some of the glosses, such as ada for "egg", could indicate a common heritage, and Gothic mēna ("moon"), compared to Crimean Gothic mine, can suggest an East Germanic connection.

Generally, the Gothic language refers to the language of Ulfilas, but the attestations themselves are largely from the 6th century, long after Ulfilas had died.[citation needed]

Alphabet and transliteration[]

A few Gothic runic inscriptions were found across Europe, but due to early Christianization of the Goths, the Runic writing was quickly replaced by the newly invented Gothic alphabet.

Ulfilas's Gothic, as well as that of the Skeireins and various other manuscripts, was written using an alphabet that was most likely invented by Ulfilas himself for his translation. Some scholars (such as Braune) claim that it was derived from the Greek alphabet only while others maintain that there are some Gothic letters of Runic or Latin origin.

A standardized system is used for transliterating Gothic words into the Latin script. The system mirrors the conventions of the native alphabet, such as writing long /iː/ as ei. The Goths used their equivalents of e and o alone only for long higher vowels, using the digraphs ai and au (much as in French) for the corresponding short or lower vowels. There are two variant spelling systems: a "raw" one that directly transliterates the original Gothic script and a "normalized" one that adds diacritics (macrons and acute accents) to certain vowels to clarify the pronunciation or, in certain cases, to indicate the Proto-Germanic origin of the vowel in question. The latter system is usually used in the academic literature.

The following table shows the correspondence between spelling and sound for vowels:

| Gothic letter or digraph |

Roman equivalent |

"Normalised" transliteration |

Sound | Normal environment of occurrence (in native words) |

Paradigmatically alternating sound in other environments |

Proto-Germanic origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|