Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (film)

| Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets | |

|---|---|

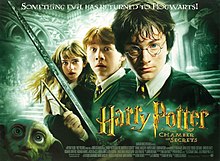

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Chris Columbus |

| Screenplay by | Steve Kloves |

| Based on | Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets by J. K. Rowling |

| Produced by | David Heyman |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Roger Pratt |

| Edited by | Peter Honess |

| Music by | John Williams |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. Pictures[2] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 161 minutes[3] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $100 million[2] |

| Box office | $879.6 million[2] |

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets is a 2002 fantasy film directed by Chris Columbus and distributed by Warner Bros. Pictures, based on J. K. Rowling's 1998 novel of the same name. Produced by David Heyman and written by Steve Kloves, it is the sequel to Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone (2001) and the second instalment in the Harry Potter film series. The film stars Daniel Radcliffe as Harry Potter, with Rupert Grint as Ron Weasley, and Emma Watson as Hermione Granger. Its story follows Harry's second year at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry as the Heir of Salazar Slytherin opens the Chamber of Secrets, unleashing a monster that petrifies the school's denizens.

The cast of the first film returned for the sequel, with the additions of Kenneth Branagh, Jason Isaacs, and Gemma Jones, among others. It was the last film to feature Richard Harris as Professor Albus Dumbledore, due to his death that same year. Principal photography began in November 2001, only three days after the release of the first film. It was shot at Leavesden Film Studios and historic buildings around the United Kingdom, as well as on the Isle of Man. Filming concluded in July 2002.

Chamber of Secrets was released in theatres in the United Kingdom and the United States on 15 November 2002. The film became a critical and commercial success, grossing $879 million worldwide and becoming the second-highest-grossing film of 2002 behind The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers. It was nominated for many awards, including the BAFTA Award for Best Production Design, Best Sound, and Best Special Visual Effects. It was followed by Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban in 2004.

Plot[]

Spending the summer with the Dursleys, Harry Potter meets Dobby, a house-elf who warns him that it is too dangerous to return to Hogwarts. Dobby sabotages an important dinner for the Dursleys, who lock Harry up to prevent his return to Hogwarts. Harry's friend Ron Weasley and his brothers Fred and George rescue him in their father's flying Ford Anglia.

Harry and the Weasley family are joined by Rubeus Hagrid and Hermione Granger at a book-signing by Gilderoy Lockhart, who later announces he is Hogwarts' new Defence Against the Dark Arts teacher. Confronted by Draco Malfoy, Harry notices Malfoy's father, Lucius, slip a book into Ginny Weasley's cauldron. When Harry and Ron are blocked from entering Platform Nine and Three-Quarters at London King's Cross railway station, they take the flying car to Hogwarts; after crashing into the Whomping Willow and breaking Ron's wand, they receive detention.

In detention, Harry hears strange voices and later finds caretaker Argus Filch's cat, Mrs. Norris, petrified beside a message written in blood: "The Chamber of Secrets has been opened, enemies of the heir... beware." Professor McGonagall explains that one of Hogwarts' founders, Salazar Slytherin, supposedly constructed a secret Chamber containing a monster that only his Heir can control, capable of purging the school of Muggle-born students. Suspecting Malfoy is the Heir, Harry, Ron, and Hermione plan to question him while disguised using forbidden polyjuice potion, which they brew in a disused bathroom haunted by a ghost, Moaning Myrtle.

During a Quidditch game, Harry's arm is broken by a Bludger. Visiting him in the infirmary, Dobby reveals that he closed the barrier to Platform 9 3/4 and made the Bludger chase Harry to force him to leave the school. He also reveals that the Chamber had been opened in the past. When Harry communicates with a snake, the school believes he is the Heir. Harry and Ron learn Malfoy is not the Heir, but his father had told him a Muggle-born girl died when the Chamber was last opened. Harry finds an enchanted diary owned by former student Tom Riddle, who fifty years prior accused Hagrid, then a student, of opening the Chamber. When the diary is stolen and Hermione is petrified, Harry and Ron question Hagrid. Professor Dumbledore, Minister of Magic Cornelius Fudge, and Lucius arrive to take Hagrid to Azkaban, but he discreetly tells the boys to "follow the spiders". In the Forbidden Forest, Harry and Ron meet Hagrid's giant pet spider, Aragog, who reveals Hagrid's innocence and provides a clue about the Chamber's monster.

A book page in Hermione's hand identifies the monster as a Basilisk, a giant serpent that kills people who make direct eye contact with it; the petrified victims only saw it indirectly. The school staff learn Ginny has been taken into the Chamber, and nominate Lockhart to save her. Harry and Ron find Lockhart preparing to flee, exposing him as a fraud; deducing that Myrtle was the girl the Basilisk killed, they find the Chamber's entrance in the bathroom she haunts. Once inside, Lockhart seizes Ron's broken wand to try to escape but it backfires, wiping Lockhart's memory and causing a cave-in which separates Harry from Ron and Lockhart.

Harry finds and enters the Chamber alone and finds Ginny unconscious, guarded by Riddle, who reveals that he used the diary to manipulate Ginny into reopening the Chamber, and that he is Slytherin's heir and Voldemort's younger self. After Harry expresses his loyalty to Dumbledore, Fawkes arrives with the Sorting Hat, causing Riddle to summon the Basilisk. Fawkes blinds the Basilisk, and the Sorting Hat eventually produces the Sword of Gryffindor, with which Harry battles the Basilisk, killing it and getting poisoned by one of its fangs in the process.

Despite his injury, Harry stabs the diary with the Basilisk fang, defeating Riddle and reviving Ginny. Fawkes' tears heal Harry, and he returns to Hogwarts with his friends and a baffled Lockhart, earning Dumbledore's praise and Hagrid's release. Harry accuses Lucius, Dobby's master, of planting the diary in Ginny's cauldron, and tricks him into freeing Dobby. The Basilisk's victims are healed, Hermione reunites with Harry and Ron, and Hagrid returns to Hogwarts.

Cast[]

- Daniel Radcliffe as Harry Potter: A 12-year-old British wizard famous for surviving his parents' murder at the hands of the evil wizard Lord Voldemort as an infant, who now enters his second year at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry.[4]

- Rupert Grint as Ron Weasley: Harry's best friend at Hogwarts and a younger member of the Weasley wizarding family.[4]

- Emma Watson as Hermione Granger: Harry's other best friend and the trio's brains.[4]

- Kenneth Branagh as Gilderoy Lockhart: A celebrity author and the new Defence Against the Dark Arts teacher at Hogwarts.[5] Hugh Grant was the first choice for the role to play Lockhart,[6] but due to reported scheduling conflicts he was unable to play the character.[7] Alan Cumming was also considered for the role.[7]

- John Cleese as Nearly Headless Nick: The ghost of Gryffindor House.[8]

- Robbie Coltrane as Rubeus Hagrid: The half-giant gamekeeper at Hogwarts. Martin Bayfield portrays a young Hagrid.[4]

- Warwick Davis as Filius Flitwick: The Charms teacher at Hogwarts and head of Ravenclaw.[8]

- Richard Griffiths as Vernon Dursley: Harry's abusive Muggle uncle, who despises wizards and now works as a drill company director.[8]

- Richard Harris as Albus Dumbledore: Headmaster of Hogwarts and one of the greatest wizards of the age.[4] Harris died shortly before the film was released.[9]

- Jason Isaacs as Lucius Malfoy: Draco's father and a former Hogwarts pupil of Slytherin House who now works as a school governor at Hogwarts.[10]

- Gemma Jones as Madam Pomfrey: The magical Healer of the Hogwarts hospital wing.[10]

- Alan Rickman as Severus Snape: The Potions teacher at Hogwarts and head of Slytherin.[8]

- Fiona Shaw as Petunia Dursley: Harry's Muggle aunt.[8]

- Maggie Smith as Minerva McGonagall: The Transfiguration teacher at Hogwarts and head of Gryffindor.[4]

- Julie Walters as Molly Weasley: Ron's mother.[8]

Several actors from Philosopher's Stone reprise their roles in this film. Harry Melling portrays Dudley Dursley, Harry's cousin.[11] James and Oliver Phelps play Fred and George Weasley, Ron's twin brothers;[12] Chris Rankin appears as Percy Weasley, Ron's other brother and a Gryffindor prefect;[13] and Bonnie Wright portrays their sister Ginny.[14] Tom Felton plays Draco Malfoy, Harry's rival in Slytherin,[15] while Jamie Waylett and Joshua Herdman appear as Crabbe and Goyle, Draco's minions.[16][17] Matthew Lewis and Devon Murray play Neville Longbottom and Seamus Finnigan, respectively, two Gryffindor students in Harry's year.[15][18] David Bradley portrays Argus Filch, Hogwarts' caretaker,[19] and Sean Biggerstaff as Oliver Wood, the Keeper of the Gryffindor Quidditch team.[20] Leslie Phillips voices the Sorting Hat.[21]

Christian Coulson appears as Tom Marvolo Riddle, a manifestation of young Lord Voldemort;[10] Mark Williams portrays Arthur Weasley, Ron's father.[10] Shirley Henderson plays Moaning Myrtle, a Hogwarts ghost.[22] Miriam Margolyes appears as Pomona Sprout, Hogwarts' Herbology professor and head of Hufflepuff.[4] Hugh Mitchell portrays Colin Creevey, a first year student that is a fan of Harry's.[23] Robert Hardy appears as Cornelius Fudge, the Minister for Magic.[24] Toby Jones voices Dobby, a House-elf,[12] while Julian Glover voices Aragog, an acromantula.[25]

Production[]

Costume and set design[]

Production designer Stuart Craig returned for the sequel to design new elements previously not seen in the first film. He designed the Burrow based on Arthur Weasley's interest in Muggles, built vertically out of architectural salvage.[26] Mr. Weasley's flying car was created from a 1962 Ford Anglia 105E.[27] The Chamber of Secrets, measuring over 76 metres (249 ft) long and 36.5 metres (119.8 ft) wide, was the biggest set created for the saga.[28] Dumbledore's office, which houses the Sorting Hat and the Sword of Gryffindor, was also built for the film.[29]

Lindy Hemming was the costume designer for Chamber of Secrets. She retained many of the characters' already established appearances, and chose to focus on the new characters introduced in the sequel. Gilderoy Lockhart's wardrobe incorporated bright colours, in contrast with the "dark, muted or sombre colours" of the other characters. Branagh said, "We wanted to create a hybrid between a period dandy and someone who looked as if they could fit into Hogwarts."[30] Hemming also perfected Lucius Malfoy's costume. One of the original concepts was for him to wear a pinstripe suit, but was changed to furs and a snake head cane in order to remark his aristocrat quality and to reflect a "sense of the old."[30]

Filming[]

Principal photography began on 19 November 2001,[31] only three days after the wide release of the first film. Second-unit work had started three weeks before, primarily for the flying car scene.[32] Filming took place mainly at Leavesden Film Studios in Hertfordshire,[33][34][35] as well as on the Isle of Man.[36] King's Cross railway station was used as the filming location for Platform 9¾, though St Pancras railway station was used for the exterior shots.[37][38] Gloucester Cathedral was used as the setting for Hogwarts School,[39] along with Durham Cathedral,[40] Alnwick Castle,[41] Lacock Abbey,[42] and the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford.[43] The Burrow was built in Gypsy Lane, Abbots Langley, in front of Leavesden Studios.[35]

Roger Pratt was brought on as director of photography for Chamber of Secrets, in order to give the film "a darker and edgier feel" than its predecessor, which reflected "the growth of the characters and the story."[30] Director Chris Columbus opted to use handheld cameras to allow more freedom in movement,[44] which he considered "a departure for [him] as a filmmaker."[30] University of Cambridge linguistics professor Francis Nolan created Parseltongue, the language spoken by snakes in the film.[45] Principal photography wrapped in July 2002.[46][47]

Sound design[]

Due to the events that take place in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, the film's sound effects were much more expansive than in the previous instalment. Sound designer and co-supervising sound editor Randy Thom returned for the sequel using Pro Tools to complete the job, which included initial conceptions done at Skywalker Sound in California and primary work done at Shepperton Studios in England.[48]

Thom wanted to give the Whomping Willow a voice, a deep growl for which he used his own voice slowed down, equalised and bass-boosted. For the mandrakes, he combined baby cries with female screams, in order to "make it just exotic enough so that you think, 'Hmm, I've never heard anything quite like that before.'"[48]

Thom described the basilisk as a challenge, "because it's a giant snake, but it's also like a dragon — not many snakes have teeth like that. He had to hiss, he had to roar and there were times at the end when he was in pain." He mixed his own voice, tiger roars, and horse and elephant vocalizations.[48]

Special and visual effects[]

Visual effects took nine months to make,[44] until 9 October 2002, when the film was finished.[49] Industrial Light & Magic, Mill Film, The Moving Picture Company (MPC), Cinesite and Framestore CFC handled the approximately 950 visual effect shots in the film.[50][51] Jim Mitchell and Nick Davis served as visual effects supervisors. They were in charge of creating the CG characters Dobby the House Elf, the Basilisk, and the Cornish pixies, among others.[50] Chas Jarrett from MPC served as CG supervisor, overseeing the approach of any shot that contains CG in the film.[52] With a crew of 70 people, the company produced 251 shots, 244 of which made it to the film, from September 2001 to October 2002.[53]

The visual effects team worked alongside creature effects supervisor Nick Dudman, who devised Fawkes (Harry Potter) the Phoenix, the Mandrakes, Aragog the Acromantula, and the first 25 feet (8 m) of the Basilisk.[50][54] According to Dudman, "Aragog represented a significant challenge to the Creature department." The giant spider stood 9 feet (3 m) tall with an 18 feet (5 m) foot leg span, each of which had to be controlled by a different team member. The whole creature weighed three quarters of a ton.[50] It took over 15 people to operate the animatronic Aragog on set.[55]

The Whomping Willow sequence required a combination of practical and visual effects. Special effects supervisor John Richardson and his team created mechanically operated branches to hit the flying car.[56] A 1:3 scale set was built on stage at Shepperton Studios, which featured the fully-sized top third of the tree with a forced perspective to appear a height of over 100 feet (30 m) high. The courtyard and the tree were built in 3D. Some shots ended up being entirely digital.[53][57] Jarret identified the rendering as "the biggest challenge" of the scene, because "there was just so much going on in [it] ... It was simply massive."[57]

Music[]

John Williams, who composed the previous film's score, returned to score Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. Composing the film proved to be a difficult task, as Williams had just completed scoring Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones and Minority Report when work was to begin on Catch Me If You Can. Because of this, William Ross was brought in to arrange themes from the Philosopher's Stone into the new material that Williams was composing whenever he had the chance.[58] The soundtrack album was released on 12 November 2002.[59]

Distribution[]

Marketing[]

Footage for the film began appearing online in the summer of 2002, with a teaser trailer debuting in cinemas with the release of Scooby-Doo.[60] A video game based on the film was released in early November 2002 by Electronic Arts for several consoles, including GameCube, PlayStation 2, and Xbox.[61] The film also continued the merchandising success set by its predecessor, with reports of shortages on Lego's Chamber of Secrets tie-ins.[62]

Home media[]

The film was originally released in the UK, US and Canada on 11 April 2003 on both VHS tape and in a two-disc special edition fullscreen/widescreen DVD digipack, which included extended and deleted scenes and interviews.[63] On 11 December 2007, the film's Blu-ray version was released.[64] An Ultimate Edition of the film was released on 8 December 2009, featuring new footage, TV spots, an extended version of the film with deleted scenes edited in, and a feature-length special Creating the World of Harry Potter Part 2: Characters.[65] The film's extended version has a running time of about 174 minutes, which has previously been shown during certain television airings.[66]

Reception[]

Box office[]

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets held its world premiere at Odeon Leicester Square on 3 November 2002,[67] and was released in the United Kingdom and the United States on 15 November 2002.[68] The film broke multiple records upon its opening. In the US and Canada, the film opened to an $88.4 million opening weekend at 3,682 cinemas, the third-largest opening at the time, behind Spider-Man and Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone.[69] It was also No. 1 at the box office for two non-consecutive weekends.[70] In the United Kingdom, the film broke all opening records that were previously held by Philosopher's Stone. It made £18.9 million during its opening including previews and £10.9 million excluding previews. [71] It went on to make £54.8 million in the UK; at the time, the fifth-biggest tally of all time in the region.[72]

The film made a total of $879 million worldwide.[2][73] It was the second-highest-grossing film of 2002 worldwide behind The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers,[74] and the fourth highest-grossing film in the US and Canada that year with $262 million behind Spider-Man, The Two Towers, and Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones.[75] However, it was the year's number one film outside of America, making $617 million compared to The Two Towers' $584.5 million.[76]

Critical response[]

On Rotten Tomatoes the film has an approval rating of 82% based on 238 reviews, with an average rating of 7.2/10. The site's critical consensus reads, "Though perhaps more enchanting for younger audiences, Chamber of Secrets is nevertheless both darker and livelier than its predecessor, expanding and improving upon the first film's universe."[77] On Metacritic the film has a weighted average score of 63 out of 100, based on 35 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[78] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film a rare "A+", the only film in the Harry Potter series to receive such grade.[79]

Roger Ebert gave The Chamber of Secrets 4 out of 4 stars, especially praising the set design.[80] Entertainment Weekly commended the film for being better and darker than its predecessor: "And among the things this Harry Potter does very well indeed is deepen the darker, more frightening atmosphere for audiences. This is as it should be: Harry's story is supposed to get darker".[81] Richard Roeper praised Columbus' direction and the film's faithfulness to the book, saying: "Chris Columbus, the director, does a real wonderful job of being faithful to the story but also taking it into a cinematic era".[82] Variety said the film was excessively long, but praised it for being darker and more dramatic, saying that its confidence and intermittent flair to give it a life of its own apart from the books was something The Philosopher's Stone never achieved.[83] A. O. Scott from The New York Times said: "instead of feeling stirred you may feel battered and worn down, but not, in the end, too terribly disappointed".[8]

Peter Travers from Rolling Stone condemned the film for being over-long and too faithful to the book: "Once again, director Chris Columbus takes a hat-in-hand approach to Rowling that stifles creativity and allows the film to drag on for nearly three hours".[84] Kenneth Turan from the Los Angeles Times called the film a cliché which is "deja vu all over again, it's likely that whatever you thought of the first production – pro or con – you'll likely think of this one".[85]

Accolades[]

Chamber of Secrets was nominated for three BAFTA Awards: Best Production Design, Best Sound, and Best Special Visual Effects.[86] The film was also nominated for six Saturn Awards.[87] It received two nominations at the inaugural Visual Effects Society Awards.[88] The Broadcast Film Critics Association granted it the Best Family Film and Best Composer awards,[89] and nominated it for Best Digital Acting Performance (for Toby Jones).[90]

| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipients | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amanda Awards | 22 August 2003 | Best Foreign Feature Film | Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets | Nominated | [91] |

| Bogey Awards | 2002 | Bogey Award in Platinum | Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets | Won | [92] |

| British Academy Film Awards | 23 February 2003 | Best Production Design | Stuart Craig | Nominated | [86] |

| Best Sound | Randy Thom, Dennis Leonard, John Midgley, Ray Merrin, Graham Daniel and Rick Kline | Nominated | |||

| Best Special Visual Effects | Jim Mitchell, Nick Davis, John Richardson, Bill George and Nick Dudman | Nominated | |||

| Broadcast Film Critics Association Award | 17 January 2003 | Best Family Film | Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets | Won | [89] |

| Best Composer | John Williams | Won | |||

| Best Digital Acting Performance | Toby Jones | Nominated | [90] | ||

| Broadcast Music Incorporated Film & TV Awards | 14 May 2003 | BMI Film Music Award | John Williams | Won | [93] |

| Golden Reel Awards | 22 March 2003 | Best Sound Editing – Foreign Film | Randy Thom, Dennis Leonard, Derek Trigg, Martin Cantwell, Andy Kennedy, Colin Ritchie, Nick Lowe | Nominated | [94] |

| GoldSpirit Awards | 2003 | Best Recording Edition | John Williams | bronze | [95] |

| Best Sci-Fi/Fantasy Theme | bronze | ||||

| Grammy Awards | 8 February 2004 | Best Score Soundtrack Album for a Motion Picture, Television or Other Visual Media | John Williams | Nominated | [96] |

| Hugo Awards | 28 August–1 September 2003 | Best Dramatic Presentation, Long Form | Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets | Nominated | [97] |

| Japan Academy Film Prize | 7 March 2003 | Outstanding Foreign Language Film | Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets | Nominated | [98] |

| Nickelodeon Kids' Choice Awards | 12 April 2003 | Favorite Movie | Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets | Nominated | [99] |

| London Film Critics Circle | 12 February 2003 | British Supporting Actor of the Year | Kenneth Branagh | Won | [100] |

| MTV Movie Awards | 31 May 2003 | Best Virtual Performance | Toby Jones | Nominated | [101] |

| Online Film Critics Society | 6 January 2003 | Best Visual Effects | John Richardson | Nominated | [102] |

| Saturn Awards | 18 May 2003 | Best Fantasy Film | Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets | Nominated | [87] |

| Best Performance by a Younger Actor | Daniel Radcliffe | Nominated | |||

| Best Direction | Chris Columbus | Nominated | |||

| Best Costume | Lindy Hemming | Nominated | |||

| Best Make-up | Nick Dudman, Amanda Knight | Nominated | |||

| Best Special Effects | John Mitchell, Nick Davis, John Richardson, Bill George | Nominated | |||

| Stinkers Bad Movie Awards | 16 March 2003 | Most Annoying Non-Human Character | Dobby the House Elf | Nominated | [103] |

| Visual Effects Society | 19 February 2003 | Best Character Animation in a Live Action Motion Picture | "Dobby's Face" – David Andrews, Steve Rawlins, Frank Gravatt, Douglas Smythe | Nominated | [88] |

| Best Compositing in a Motion Picture | "Quidditch Match" – Dorne Huebler, Barbara Brennan, Jay Cooper, Kimberly Lashbrook | Nominated |

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". British Council. Archived from the original on 5 May 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (PG)". British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Potter teaser arrives in UK". BBC News. 21 June 2002. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ "Gilderoy Lockhart actor found for Potter 2". Newsround. CBBC. 25 October 2001. Archived from the original on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 26 September 2007.

- ^ "Hugh Grant up for Harry Potter role". The Guardian. 29 June 2001. Archived from the original on 6 January 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Grant ditches Potter in favour of Bullock". The Guardian. 17 October 2001. Archived from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Scott, A. O. (15 November 2002). "Film Review; An Older, Wiser Wizard, But Still That Crafty Lad". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ "Actor Richard Harris dies". BBC News. 25 October 2002. Archived from the original on 6 December 2002. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Chamber of Secrets' Tom Riddle actor named". Newsround. CBBC. 4 March 2002. Archived from the original on 5 March 2019. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ "Harry Melling - CV". Curtis Brown. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Youell, Clare (6 October 2003). "Potter mania as stars meet their fans". Newsround. CBBC. Archived from the original on 8 January 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ Barber, Martin (16 December 2002). ""It is odd." - Life as Percy Weasley". BBC. Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Russell, Jamie. "Interview - Bonnie Wright". BBC. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Youell, Clare (15 November 2002). "Potter boys reveal COS acting secrets". Newsround. CBBC. Archived from the original on 23 February 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ Orr, James (12 October 2011). "Harry Potter actor Jamie Waylett charged with having petrol bomb during London riots". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 22 April 2017. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ Macatee, Rebecca (26 April 2016). "Harry Potter's Gregory Goyle Is Now an MMA Cage Fighter". E! Online. Archived from the original on 16 June 2019. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ Spencer, Ashley (12 September 2016). "Exclusive! Harry Potter's Devon Murray opens up about life after Hogwarts: 'I've got a stud farm in Ireland'". Nine.com.au. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ^ Vineyard, Jennifer (29 September 2014). "David Bradley on The Strain, Game of Thrones, and the Unexpected Fallout From the Red Wedding". Vulture. Archived from the original on 1 October 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ W., Mary (2 July 2019). "Leviosa 2019: Sean Biggerstaff Q&A Session". MuggleNet. Archived from the original on 23 July 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ Moir, Jan (30 December 2002). "'Hel-low. Aren't you a gorgeous creature?'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ Mzimba, Lizo (29 November 2002). "Draco tells us he wants to meet more fans!". Newsround. CBBC. Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Mzimba, Lizo (15 November 2002). "Daniel Radcliffe COS: full interview". Newsround. CBBC. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ "Death In Holy Orders" (PDF) (Press release). BBC One. pp. 2, 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ Grubbs, Jefferson (9 August 2015). "Every Lucky Actor Who's In 'GoT' & 'Harry Potter'". Bustle. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ "Behind the scenes: The Burrow". Pottermore. Archived from the original on 2 October 2019. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ^ "Harry Potter's 'flying' car taken". BBC News. 28 October 2005. Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Garrigues, Manon (22 April 2020). "3 things you didn't know about Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". Vogue. Archived from the original on 6 May 2020.

- ^ Han, Angie (4 March 2011). "'The Making of Harry Potter' Studio Tour To Open Next Spring". /Film. Archived from the original on 11 September 2011. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "About the Cinematography". Warner Bros. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 16 May 2020 – via CinemaReview.

- ^ Germain, David (18 November 2001). "'Potter' topples another box office record with $93.5 million debut". Arizona Daily Sun. Archived from the original on 7 May 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ Kehr, Dave (23 November 2001). "At the Movies: Trading Britain For America". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 May 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ Cagle, Jess (5 November 2001). "Cinema: The First Look at Harry". Time. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- ^ Kennedy, Maev (2 November 2001). "Harry Potter and the gobbet of ire". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 October 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Leggett, Tabatha (21 January 2014). "The "Harry Potter" Guide To The U.K." BuzzFeed. Archived from the original on 10 June 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ Richardson, Matthew (30 May 2020). "Chapter Six: Wartime and the Swinging Sixties". The Isle of Man: Stone Age to Swinging Sixties. Pen and Sword History. ISBN 9781526720788. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Flying Ford Anglia". St Pancras International. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ Deiss, Richard (2013). The Cathedral of the Winged Wheel and the Sugarbeet Station: Trivia and Anecdotes on 222 Railway Stations in Europe. Books on Demand. p. 61. ISBN 9783848253562. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ Green, Willow (1 February 2002). "Potty About Potter". Empire. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ Hodgson, Barbara (9 October 2019). "Afternoon tea in Harry Potter classroom is on offer as Durham Cathedral reveals magical 'hidden' room". ChronicleLive. Archived from the original on 9 October 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ "Harry Potter at Alnwick Castle". Alnwick Castle. Archived from the original on 9 May 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ Barnett, Stephen; Tucker, David (2012). "Lacock and Avebury – Timeless". Out of London Walks: Great escapes by Britain's best walking tour company. Random House. ISBN 9780753548028. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ "Filming & photography". Bodleian Library. Archived from the original on 17 January 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lawson, Terry (14 November 2002). "The second instalment is charmed, director says". The Vindicator. pp. D10, D14. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Adger, David (2019). "Impossible Patterns". Language Unlimited: The Science Behind Our Most Creative Power. Oxford University Press. p. 99. ISBN 9780192563194. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ Schmitz, Greg Dean. "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002)". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on 21 June 2007. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ "El mexicano Alfonso Cuarón será el director de Harry Potter III". La Crónica de Hoy (in Spanish). 22 July 2020. Archived from the original on 16 May 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Jackson, Blair (1 January 2003). "The Chamber of Secrets". Mix. NewBay Media. Archived from the original on 12 October 2008. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ "Potter film should be finished next week". Newsround. CBBC. 4 October 2002. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "About the Special Effects". Warner Bros. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2020 – via CinemaReview.

- ^ Robertson, Barbara (April 2003). "When Harry Met Dobby". Cinefex. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ Teo, Leonard. "3D Festival: The VFX of Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". 3D Festival. p. 1. Archived from the original on 21 April 2003. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Teo, Leonard. "3D Festival: The VFX of Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". 3D Festival. p. 2. Archived from the original on 26 February 2003. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Creating the World of Harry Potter: the Basilisk. Warner Bros. Retrieved 16 May 2020 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Creature Effects". Warner Bros. Studio Tour London – The Making of Harry Potter. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ "Special & Visual Effects". Warner Bros. Studio Tour London – The Making of Harry Potter. Archived from the original on 26 March 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Teo, Leonard. "3D Festival: The VFX of Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". 3D Festival. p. 3. Archived from the original on 7 March 2003. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (John Williams/William Ross)". Filmtracks. 7 November 2002. Archived from the original on 14 January 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets Soundtrack (2002)". Soundtrack.Net. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ "Potter trailer gets Scooby outing". BBC News. 13 June 2002. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ^ Krause, Staci (26 November 2002). "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". IGN. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ^ Cagle, Jess (3 November 2002). "When Harry Meets SCARY". Time. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ^ Kipnis, Jill (1 March 2003). "Blockbuster Sequels Ensure DVD's Sale Saga". Billboard. p. 66. Archived from the original on 13 June 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets Blu-ray Release Date". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on 18 November 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ Calogne, Juan (18 September 2009). "Ultimate Editions Announced for First Two Harry Potter movies". Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- ^ "Exclusive First Look at 'Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire' to Be Presented During Network Television Debut of 'Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets,' Airing May 7 on ABC". Business Wire. 2 May 2005. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ^ Youngs, Ian (3 November 2002). "Fans spellbound at Potter première". BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ O'Shea, Lucy (15 November 2002). ""Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets" Movie Released Worldwide". MuggleNet. Archived from the original on 17 May 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Gray, Brandon (18 November 2002). "Harry Potter Potent with $88.4 Million Weekend". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 17 May 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ "Domestic 2002 Weekend 48". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 17 May 2020. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ^ "Potter conjures up box office record". BBC News. 18 November 2002. Archived from the original on 5 November 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- ^ "All time box office". Sky Is Falling. Archived from the original on 1 September 2007. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- ^ Strowbridge, C.S. (28 January 2003). "Chamber of Secrets sneaks pasts Jurassic Park". The Numbers. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- ^ "2002 Worldwide Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ "2002 Domestic Grosses". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 4 April 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ "2002 Overseas Total Yearly Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". Metacritic. Red Ventures. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002)". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (15 November 2002). "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 13 October 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (13 November 2002). "'Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets': EW review". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Roeper, Richard (15 November 2002). "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". At the Movies.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (7 November 2002). "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". Variety. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Travers, Peter (15 November 2002). "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (15 November 2002). "'Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets' doesn't capture the well-balanced tone of the book". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Film in 2003". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on 14 May 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Moro, Eric (5 March 2003). "The 29th Annual Saturn Awards Nominations - Feature Film Category". Mania. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "1st Annual VES Awards". Visual Effects Society. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The BFCA Critics' Choice Awards 2002". Broadcast Film Critics Association. 17 January 2003. Archived from the original on 14 April 2013. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Godfrey, Leigh (22 January 2003). "Gollum and Spirited Away Are The Critics Choice". Animation World Network. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "Amanda Awards (Norway) 2003". Mubi. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "Harry Potter und die Kammer des Schreckens". Blickpunkt: Film (in German). Archived from the original on 7 September 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ "2003 BMI Film/TV Awards: Song List". Broadcast Music, Inc. 14 May 2003. Archived from the original on 1 May 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ Martin, Denise (7 February 2003). "'Gangs,' 'Perdition' top Golden Reel nods". Variety. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "Premios GoldSpirit - II Edición (2002): Sala de Trofeos". BSOSpirit (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 20 October 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "Complete list of 46th annual Grammy winners and nominees". Chicago Tribune. 4 December 2003. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "2003 Hugo Awards". Hugo Awards. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "26th Japan Academy Prize". Japan Academy Film Prize. Archived from the original on 17 January 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "Nickelodeon's 16th Annual Kids' Choice Awards Takes Stars, Music and Mess to the Next Level on Saturday, April 12 Live from Barker Hangar in Santa Monica". Nickelodeon. 13 February 2003. Archived from the original on 30 September 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "First award blood to Caine". BBC News. 12 February 2003. Archived from the original on 25 December 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "MTV Movie Awards nominations 2003". Newsround. CBBC. 15 April 2003. Archived from the original on 13 January 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "2002 Awards (6th Annual)". Online Film Critics Society. Archived from the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ "2002 25th Hastings Bad Cinema Society Stinkers Awards". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 15 August 2007. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (film) |

- 2002 films

- English-language films

- Harry Potter (film series)

- 1492 Pictures films

- 2002 fantasy films

- 2000s fantasy adventure films

- American films

- American fantasy adventure films

- American sequel films

- British films

- British fantasy adventure films

- British sequel films

- Films shot in Surrey

- Films shot in Highland (council area)

- Fictional-language films

- Films directed by Chris Columbus

- Warner Bros. films

- Heyday Films films

- Films about shapeshifting

- Films about spiders

- Films set in 1992

- Films set in 1993

- Films set in England

- Films set in Scotland

- Films set in London

- Films shot in the Isle of Man

- Films shot in Gloucestershire

- Films shot in Hertfordshire

- Films shot in Northumberland

- Films shot in Buckinghamshire

- Films shot in Oxfordshire

- Films shot in County Durham

- Films shot in London

- Films shot in North Yorkshire

- Films shot at Warner Bros. Studios, Leavesden

- Films shot in Wiltshire

- Films produced by David Heyman

- High fantasy films

- IMAX films

- Films scored by John Williams

- Flying cars in fiction

- Fiction about memory erasure and alteration

- Children's fantasy films