Hazelnut

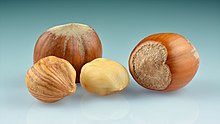

The hazelnut is the fruit of the hazel and therefore includes any of the nuts deriving from species of the genus Corylus, especially the nuts of the species Corylus avellana.[1] They are also known as cobnuts or filberts according to species. A cob is roughly spherical to oval, about 15–25 mm (5⁄8–1 in) long and 10–15 mm (3⁄8–5⁄8 in) in diameter, with an outer fibrous husk surrounding a smooth shell and a filbert is more elongated, being about twice as long as its diameter. The nut falls out of the husk when ripe, about seven to eight months after pollination. The kernel of the seed is edible and used raw or roasted, or ground into a paste. The seed has a thin, dark brown skin, which is sometimes removed before cooking.

Hazelnuts are used in baking and desserts, confectionery to make praline, and also used in combination with chocolate for chocolate truffles and products such as chocolate bars, hazelnut cocoa spread such as Nutella, and Frangelico liqueur. Hazelnut oil, pressed from hazelnuts, is strongly flavoured and used as a cooking oil. Turkey is the world's largest producer of hazelnuts.[2]

Hazelnuts are rich in protein, monounsaturated fat, vitamin E, manganese, and numerous other essential nutrients (nutrition table below).[3]

History[]

In 1995, evidence of large-scale Mesolithic nut processing, some 8,000 years old, was found in a midden pit on the island of Colonsay in Scotland. The evidence consists of a large, shallow pit full of the remains of hundreds of thousands of burned hazelnut shells. Hazelnuts have been found on other Mesolithic sites, but rarely in such quantities or concentrated in one pit. The nuts were radiocarbon dated to 7720±110 BP, which calibrates to circa 6000 BCE. Similar sites in Britain are known only at Farnham in Surrey and Cass ny Hawin on the Isle of Man.[4][5]

This discovery gives an insight into communal activity and planning in the period. The nuts were harvested in a single year, and pollen analysis suggests that all of the hazel trees were cut down at the same time.[5] The scale of the activity and the lack of large game on the island, suggest the possibility that Colonsay may have contained a community with a largely vegetarian diet for the time they spent on the island. Originally, the pit was on a beach close to the shore and was associated with two smaller, stone-lined pits whose function remains obscure, a hearth, and a second cluster of pits.[4]

The traditional method to increase nut production is called 'brutting', which involves prompting more of the tree energy to go into flower bud production, by snapping, but not breaking off, the tips of the new year shoots six or seven leaf groups from where they join with the trunk or branch, at the end of the growing season.[6] The traditional term for an area of cultivated hazelnuts is a plat.

Culinary uses[]

Hazelnuts are used in confections to make pralines, chocolate truffles, and hazelnut paste products. In Austria, hazelnut paste is an ingredient for making tortes, such as Viennese hazelnut torte. In Kyiv cake, hazelnut flour is used to flavor its meringue body, and crushed hazelnuts are sprinkled over its sides. Dacquoise, a French dessert cake, often contains a layer of hazelnut meringue. Hazelnuts are used in Turkish cuisine and Georgian cuisine; the snack churchkhela and sauce satsivi are used, often with walnuts. Hazelnuts are also a common constituent of muesli. The nuts may be eaten fresh or dried, having different flavors.[7]

Controversy[]

Ferrero SpA, the maker of Nutella and Ferrero Rocher, uses 25% of the global supply of hazelnuts.[8] Nearly seventy percent of the world's hazelnuts come from Turkey where, on approximately 400,000 family-owned orchards, illegal child labour is common. This commercial product, Nutella, came under pressure after a 2019 BBC investigation found that migrant child labour is used on many hazelnut orchards in Turkey, the spread’s main supply source. Its parent company, Ferrero, has stated that, while it does run programmes aimed at removing child workers from farms, the complexity of the supply chain means it is unable to say with certainty whether or not any children pick some of its hazelnuts.[9][10]

Nutrients[]

| |

| Nutritional value per 100 g | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 2,629 kJ (628 kcal) |

16.70 g | |

| Sugars | 4.34 g |

| Dietary fiber | 9.7 g |

60.75 g | |

14.95 g | |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 0% 1 μg0% 11 μg92 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 56% 0.643 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 9% 0.113 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 12% 1.8 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 18% 0.918 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 43% 0.563 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 28% 113 μg |

| Vitamin C | 8% 6.3 mg |

| Vitamin E | 100% 15.03 mg |

| Vitamin K | 14% 14.2 μg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 11% 114 mg |

| Iron | 36% 4.7 mg |

| Magnesium | 46% 163 mg |

| Manganese | 294% 6.175 mg |

| Phosphorus | 41% 290 mg |

| Potassium | 14% 680 mg |

| Selenium | 3% 2.4 μg |

| Sodium | 0% 0 mg |

| Zinc | 26% 2.45 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 5.31 g |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA FoodData Central | |

In a 100-gram (3+1⁄2-ounce) reference amount, raw hazelnuts supply 2,630 kilojoules (628 kilocalories) of food energy and are a rich source (20% or more of the Daily Value, DV) of numerous essential nutrients (see table).

Hazelnuts contain particularly high amounts of protein, dietary fiber, vitamin E, iron, thiamin, phosphorus, manganese, and magnesium, all exceeding 30% DV (table). Several B vitamins have appreciable content. In lesser, but still significant amounts (moderate content, 10-19% DV), are vitamin K, calcium, zinc, and potassium (table).

Hazelnuts are a significant source of total fat, accounting for 93% DV in a 100-gram amount. The fat components are monounsaturated fat as oleic acid (75% of total), polyunsaturated fat mainly as linoleic acid (13% of total), and saturated fat, mainly as palmitic acid and stearic acid (together, 7% of total).[3]

Cultivars[]

The many cultivars of the hazel include 'Atababa', 'Barcelona', 'Butler', 'Casina', 'Clark', 'Cosford', 'Daviana', 'Delle Langhe', 'England', 'Ennis', 'Halls Giant', 'Jemtegaard', 'Kent Cob', 'Lewis', 'Tokolyi', 'Tonda Gentile', 'Tonda di Giffoni', 'Tonda Romana', 'Wanliss Pride', and 'Willamette'.[11] Some of these are grown for specific qualities of the nut, including large nut size, or early or late fruiting, whereas others are grown as pollinators. The majority of commercial hazelnuts are propagated from root sprouts.[11] Some cultivars are of hybrid origin between common hazel and filbert.[12]

In the United Kingdom and Ireland, hazelnuts are sometimes referred to as cobnuts, for which a specific cultivated variety – Kent cobnuts – is the main variety cultivated in fields known as plats, hand-picked, and eaten green.[13] According to the BBC, a national collection of cobnut varieties exists at Roughway Farm in Kent.[14] They are called cobnuts because cob was a word used to refer to the head or "noggin", and children had a game in which they would tie a string to a hazelnut and use it to try to hit an opponent on the head.[15]

Harvesting[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

This section's factual accuracy is disputed. (May 2021) |

Hazelnuts are harvested annually in mid-autumn. As autumn comes to a close, the trees drop their nuts and leaves. Most commercial growers wait for the nuts to drop on their own, rather than using equipment to shake them from the tree. The harvesting of hazelnuts is performed either by hand or by manual or mechanical raking of fallen nuts.[citation needed]

Four primary pieces of equipment are used in commercial harvesting: the sweeper, the harvester, the nut cart, and the forklift. The sweeper moves the nuts into the center of the rows, the harvester lifts and separates the nuts from any debris (i.e. twigs and leaves), the nut cart holds the nuts picked up by the harvester, and the forklift brings a tote to offload the nuts from the nut cart and then stacks the totes to be shipped to the processor (nut dryer).[citation needed]

The sweeper is a low-to-the-ground machine that makes two passes in each tree row. It has a 2 m (6 ft 7 in) belt attached to the front that rotates to sweep leaves, nuts, and small twigs from left to right, depositing the material in the center of the row as it drives forward. On the rear of the sweeper is a powerful blower to blow material left into the adjacent row with air speeds up to 90 m/s (300 ft/s). Careful grooming during the year and patient blowing at harvest may eliminate the need for hand raking around the trunk of the tree, where nuts may accumulate. The sweeper prepares a single center row of nuts narrow enough for the harvesting tractor to drive over without driving on the center row. It is best to sweep only a few rows ahead of the harvesters at any given time, to prevent the tractor that drives the harvester from crushing the nuts that may still be falling from the trees. Hazelnut orchards may be harvested up to three times during the harvest season, depending on the quantity of nuts in the trees and the rate of nut drop as a result of weather.[16]

The harvester is a slow-moving machine pushed by a tractor, which lifts the material off the ground and separates the nuts from the leaves, empty husks, and twigs. As the harvester drives over the rows, a rotating cylinder with hundreds of tines, rakes the material onto a belt. The belt takes the material over a blower and under a powerful vacuum that sucks any lightweight soil and leaves from the nuts, and discharges them into the orchard. The remaining nuts are conveyed into a nut cart that is pulled behind the harvester. Once a tote is filled with nuts, the forklift hauls away the full totes and brings empty ones back to the harvester to maximize the harvester's time.[citation needed]

Two different timing strategies are used for collecting the fallen nuts. The first is to harvest early, when about half of the nuts have fallen. With less material on the ground, the harvester can work faster with less chance of a breakdown. The second option is to wait for all the nuts to fall before harvesting. Although the first option is considered the better of the two,[17] two or three passes do take more time to complete than one. Weather also must be a consideration. Rain inhibits harvest and should a farmer wait for all the nuts to fall after a rainy season, it becomes much more difficult to harvest. Pickup also varies with how many acres are being farmed as well as the number of sweepers, harvesters, nut carts, and forklifts available.[citation needed]

| Country | Production (tonnes) |

|---|---|

| 776,046 | |

| 98,530 | |

| 53,793 | |

| 39,920 | |

| 35,000 | |

| 29,318 | |

| World | 1,125,178 |

Production[]

In 2019, world production of hazelnuts (in shells) was 1.1 million tonnes.[18] The hazelnut production in Turkey accounts for 69% of the world total, followed by Italy, Azerbaijan, the United States, Chile, and China.[18] The large number of hazelnut farms in Turkey and the influx of Syrian refugees raised concerns of child labor and exploitation.[19]

In the United States, Oregon accounted for 99% of the nation's production in 2014, having a crop value of $129 million that is purchased mainly by the snack food industry.[20]

See also[]

- Filbertone, the principal flavor compound of hazelnuts

- Nutella

- Frangelico

- List of hazelnut diseases

- The Hazel-nut Child

References[]

- ^ Martins, S.; SimAues, F.; Matos, J.; Silva, A. P.; Carnide, V. (2014). "Genetic relationship among wild, landraces, and cultivars of hazelnut (Corylus avellana) from Portugal revealed through ISSR and AFLP markers". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 300 (5): 1035–1046. doi:10.1007/s00606-013-0942-3. hdl:10348/6564. S2CID 18832843.

- ^ "INVENTORY OF HAZELNUT RESEARCH, GERMPLASM AND REFERENCES". www.fao.org. Retrieved 2020-08-28.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Full Report (All Nutrients): 12120, Nuts, hazelnuts or filberts". USDA FoodData Central. 2015. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Mesolithic food industry on Colonsay" Dec 1995) British Archaeology. No. 5. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Moffat, Alistair (2005) Before Scotland: The Story of Scotland Before History. London. Thames & Hudson. p. 91–2.

- ^ The Essential Guide to Hazel. By Paul Alfrey - Balkan Ecology Project. Permaculture Magazine, Tuesday, 8 August 2017. Accessed 2 March 2021.

- ^ Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall (8 September 2007). "Nuts, whole hazelnuts". The Guardian.

- ^ Narula, Svati Kirsten (14 August 2014). "A frost in Turkey may drive up the price of your Nutella". Quartz (publication). Atlantic Media.

- ^ Whewell, Tim (19 September 2019). "Is Nutella made with nuts picked by children?". BBC News, Turkey. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

[Orchard-owner has] no option but to pay the children, because their parents insist that they work. 'I am trying not to make them work, but then they say they are leaving,' he says. 'The mother and father want them to work - and to be paid.'¶ He adds: 'This chain has to be broken.'

- ^ "The bitter song of the hazelnut (26 minutes, downloadable)" (Podcast). BBC. 19 Sep 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Huxley, A., ed. (1992). New RHS Dictionary of Gardening. Macmillan ISBN 0-333-47494-5.

- ^ Flora of NW Europe: Corylus avellana Archived 2008-05-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Kent cobnuts". Roughway Farm. 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ "BBC: On your farm - The Kentish cobnut". BBC. 15 July 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- ^ "Filbert vs. Hazelnut: Is There a Difference?". Garden.eco. 17 June 2018. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ^ "Hazelnuts in Ontario – Growing, Harvesting and Food Safety". gov.on.ca.

- ^ "Fındık". Yeni Ansiklopedi (in Turkish). January 2011. Archived from the original on 2012-01-04. Retrieved 2017-12-15.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Hazelnuts (with shell); Crops by Region, World List, Production Quantity, 2019". UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Statistics Division (FAOSTAT). 2019. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ Segal, David (2019-04-29). "Syrian Refugees Toil on Turkey's Hazelnut Farms With Little to Show for It". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-08-04.

- ^ "Hazelnuts". Ag Marketing Resource Center, Iowa State University, Ames, IA. August 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Corylus avellana. |

| Look up hazelnut in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Hazelnuts

- Corylus

- Crops originating from Europe

- Edible nuts and seeds