History of Noakhali

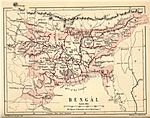

| History of Bengal |

|---|

|

| Outline of South Asian history |

|---|

|

The Greater Noakhali region predominantly includes the districts of Noakhali, Feni and Lakshmipur in Bangladesh, though it has historically also included Bhola, Sandwip and some southern parts of Tripura in India and southern Comilla. The history of the Noakhali region begins with the existence of civilisation in the villages of Shilua and Bhulua. Bhulua became a focal point during the Buddhist and Hindu kingdoms of Pundra, Harikela and Samatata leading it to become the initial name of the region as a whole. The medieval Kingdom of Bhulua enjoyed autonomy under the Twipra Kingdom and Bengal Sultanate before being conquered by the Mughal Empire. At the beginning of the 17th century, Portuguese pirates led by Sebastian Gonzales took control of the ara but were later defeated by Governor Shaista Khan. Affected by floodwaters, the capital of the region was swiftly moved to a new place known as Sudharam/Noakhali, from which the region presently takes its name. By 1756, the British East India Company had dominated and started to establish several factories in the region. The headquarters was once again moved in 1951, to Maijdee, as a result of Noakhali town vanishing due to fluvial erosion.[1]

Ancient and early medieval[]

Civilisation in the present-day Noakhali region dates back around 3000 years ago, making it one of the youngest sub-regions of Bengal. Webster asserts that the original inhabitants may have been either the ancestors of the Namasudra or Chandala, or the Jogis; who are the predominant Hindu caste in the region. According to Hindu mythology, this region may have been a part of the Shukhma Kingdom. The Hindu epic known as the Mahabharata states that the King of Shukhma was defeated by Bhima. The 5th-century Classical Sanskrit author Kalidasa mentions the greenery and palm trees of Shukhma in his Raghuvaṃśa.[2] An undeciphered Brahmi inscription dating back to the Mauryan and Shunga period was discovered in the village of Shilua.[3] The discovery of silver proto-Bengali coins suggest that by the 9th century, the region was a part of the realms of Harikela and Akara.[4] The region was historically known as and based around Bhulua, an ancient town a few miles west of the town of Noakhali. Bhulua was a part of the Pundra Kingdom for much of this period.

The early Rajas of the region were said to have been Kayasthas from West Bengal. According to Hindu legend, Adi Sura's ninth son, Bishwambhar Sur, went on a pilgrimage to the Chandranath Temple atop the Chandranath Hill of Sitakunda. Returning from Sitakunda, Sur passed through present-day Noakhali where he rested and had a dream that Varahi would make him the sovereign of this territory if he worships her. On a cloudy day in 1203 AD, Sur built an altar for Varahi and sacrificed a goat. When the clouds moved away, Sur realised that he had sacrificed the goat to the west, which was not acceptable in Hinduism. As a result, he screamed bhul hua (it was wrong), from which the name Bhulua was said to have come from. Today, the Hindus of Noakhali continue this local tradition by sacrificing goats to the west. Though ancestrally a Rajput, Sur married into a Kayastha family, which his dynasty continued to identify with. A temple in Amishapara, Sonaimuri still contains a stone idol of Varahi. According to tradition, Kalyanpur became the first capital of Bhulua.[2]

In this period, the native population of the region were said to have been Mongoloid spirit worshippers as opposed to the Indo-Aryans of western and northern Bengal at the time. Prior to this, Buddhism was prevalent in the region.[5]:40

Arrival of Muslims[]

Islam was said to have first reached the region when Tughral Tughan Khan assisted the nearby Twipra Kingdom in 1279. Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah, who was initially the Sultan of Sonargaon, also raided Tripura at one point so it is probable that he may have reached Bhulua. The Hindu kingdom of Bhulua remained in the hands of the Bishwambhar Sur (বিশ্বম্ভর শূর) dynasty. The fourth king of Bhulua adopted the name Sriram Khan which suggests that Muslim influence began around this time. Khan founded the village of Srirampur where he built a palace which still exists in ruins today. The sixth king ended the tradition of naming themselves as Khans and adopted the title of Rai. His son however, adopted the name Manikya which suggests that Bhulua may have become a vassal state of the Manikya dynasty's Twipra Kingdom. The two kingdoms had cordial relationships, with the Kings of Tripura allowing the Bhulua kings to place the Raj Tika (royal mark) on their foreheads during their coronation.[2]

To strengthen the defences of the Bhulua Kingdom's frontier from the invasion of the Maghs, Bhulua's king Rajballabh appointed a Muslim general to be a feudal governor of the Elahabad and Dandra parganas. This led to an influx of Muslim migrants into the region. In this period, a Sufi pir and Syed from Baghdad arrived to Bhulua riding on top of a tiger and was thus known by the people as Sher Alam. The Hindu ruler gifted to Syed Sher Alam, two droṇs of land and a large rent-free house in Danaikot, Feni. Alam stayed in Danaikot for a while before setting off to join the Muslims who had settled in Dililpur/Tangirpar (near Rajganj), where he was accepted as their chief.[6] Alam became the founder of the aristocratic Syed Alam family of Rajganj who played important roles in the political history of Noakhali. Syed Nur Alam Chowdhury was from this family.[7]

In the 14th century, Syed Ahmad Tannuri of Baghdad migrated to Kanchanpur, with the intention of propagating Islam. He is also known by locals as Miran Shah.[8] He was accompanied by his wife, Majjuba Bibi, and some companions such as Bakhtiyar Maisuri who settled in Rohini, Shah Muhammad Yusuf in Kitabpur, Shah Muhammad Fazalullah in Raipur, Shah Nuruddin in Bhatuiya, Shah Badshah Mian in Dalilpur Tangir Par, Miyan Sahib Baghdadi in Harichar, and Shah Abdullah and Shah Yaqub Nuri in Noakhali town. Following the Conquest of Sylhet in 1303, some disciples of Shah Jalal migrated to Noakhali, such as Shaykh Jalaluddin who settled in Nandanpur.[9] Other notable Muslim preachers who settled in Noakhali include Ahsan Hasan Shah, Azam Shah and Shah Amiruddin.[10]

Lakshmana Manikya was the eighth and most prominent king of Bhulua. He wrote two Sanskrit books and was a member of the 16th-century Baro-Bhuiyans of Bengal. Hundreds of Brahmins were invited to Bhulua by Manikya, who gave them land in Chapali, Kilpara, Barahinagar and Srirampur. Manikya would often make fun of Ramchandra, the young ruler of Chandradwip, which eventually led to Ramchandra plotting against him. Ramchandra crossed the Meghna River and invited him to a banquet in which his men captured Manikya and murdered him back in Chandradwip. Lakshmana was succeeded by his son, the ninth King of Bhulua, Balaram Manikya. Unlike Bhulua's former kings, Balaram refused to attend the coronation of the Twipra Raja Amar Manikya in 1597, declaring total independence. As a result, Amar Manikya raided Bhulua and Balaram was eventually forced to become a vassal ruler again.[2] Balaram Manikya's court poet was Abdur Razzaq of Balukia in Bedrabad. Abdur Razzaq wrote Sayful Mulk o Lal Banu in 1770 CE.[5]

Mughal period[]

The Mughal invasions and conquests in Bengal started during the reigns of Emperors Humayun and Akbar. Present-day Noakhali was a part of the Sarkar of Sonargaon.[11] The Battle of Rajmahal in 1576 led to the execution of Daud Khan Karrani, ending the Karrani sultanate. Bengal was fully integrated as a Mughal province known as the Bengal Subah by 1612 during the reign of Jahangir.[12]

During the reign of Mughal emperor Jahangir, the Subahdar of Bengal Islam Khan I sent a force to takeover Bhalwa, which was ruled by Ananta Manikya of the Bishwambhar Sur dynasty. The expedition consisted of the forces of Mirza Nuruddin, Mirza Isfandiyar, Haji Shamsuddin Baghdadi, Khwaja Asl, Adil Beg and Mirza Beg, in addition to 500 members of the Subahdar's cavalry. Khan appointed Abdul Wahid as the main commander of the entire expedition, which in total was made up 50 elephants, 3000 matchlockers and 4000 cavalry. Ananta Manikya set up defences around Bhalwa with the Magh Raja's assistance, before proceeding forward to the Dakatia banks where he built a fort. The Mughals reached the fort in a few days, and a battle commenced resulting in a number of deaths on both sides. The Bhalwa forces also planned a surprise attack at night. Manikya's chief minister, Mirza Yusuf Barlas, surrendered to the Mughal forces and was rewarded by Abdul Wahid as a mansabdar of 500 soldiers and 300 horses. After losing Barlas however, Manikya did not surrender and rather retreated to Bhalwa at midnight to strengthen the fort there. News of the retreat reached the Mughals two pahars later, and so they began following the Bhalwa forces. Having no time to defend themselves, Manikya retreated further to seek refuge with the Magh Raja but was defeated at the banks of the Feni River. The Mughals seized all of Manikya's elephants, and Abdul Wahid successfully took control of Bhalwa.

During the governorship of Qasim Khan Chishti, Abdul Wahid sent his son on a mission to raid Tripura whilst he set off to meet with the Governor at Jahangirnagar, leaving a Mutasaddi to take care of Bhalwa. Effectively, the Magh Raja saw this as an opportunity to raid Bhalwa, and so he set off for Bhalwa with a large force from Arakan consisting of cavalry, elephants, artillery, infantry and a fleet. The Mutasaddi sent a messenger to Jahangirnagar, warning them of the raid, but Governor Qasim Khan Chishti thought it was probably an excuse for Abdul Wahid to leave his presence. After further warnings from the thanadars of Bikrampur and Sripur, Chishti granted Abdul Wahid permission to leave. Chishti himself marched to Khizrpur where he commanded that all rivers connecting Khizrpur to Bhalwa are to be bridged with large cargo ships such as Patila and Bhadia. He also sent a message to Syed Abu Bakr, to cancel the Conquest of Assam and bring the fleet back to Bengal in order to suppress the Maghs, and also appointed Sazawals to bring the forces of Mirza Makki and Shaykh Kamal to Jahangirnagar, ready for the Bhalwa battle. Chishti then sent a force of 4000 of his own matchlockers and 2000 horsemen, that were commanded by his son, Shaykh Farid and General Abdun Nabi towards Bhalwa, safely through the Lakhya River.

By the 1620s, it said that Muslims had established an outpost near the village of Bhalwa which they called Islamabad. Historians have identified it with modern-day Lakshmipur.[13] Mirza Baqi, the former Bakhshi of the Subahdar of Bengal Ibrahim Khan Fath-i-Jang, was appointed as the Thanadar of Bhalwa in addition to being given a mansabdari of 500 soldiers with 400 horses.[13] The agricultural activities of north-eastern Bhalwa were seriously affected by floodwaters of the Dakatia River flowing from the Tripura hills in the 1660s. To salvage the situation, a canal was dug in 1660 that ran from the Dakatia through Ramganj, Sonaimuri and Chowmuhani to divert water flow to the junction of the Meghna River and Feni River. After excavating this long canal, a new town was founded which locals called "Noakhali" meaning new canal though the Bhulua name remained prevalent. In 1661, Dutch sailors were shipwrecked at Bhulua and were taken care of by the Bhulua rulers.[2]

Bhulua was established as a thana and pargana during the reign of Emperor Aurangzeb, and Farhad Khan served as its administrative officer (thanadar) from 1665 to 1670.[14] During the 1665 Mughal conquest of nearby Chittagong, the Firingis led by Captain Moor set fire to Arakanese fleets and fled to Bhulua where Farhad gave them refuge. Farhad later sent them off to the Subahdar of Bengal Shaista Khan in Jahangirnagar.[15][16][17] During Shaista Khan's governorship, Bhulua was incorporated into the Chakla of Jahangirnagar. The ruins of a 17th-century Mughal fort can be found in the village of Bhulua.[13] Raja Kirti Narayan became the Zamindar of Bhulua in 1728.

During the reign of Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah, a Muslim missionary from Iran known as Pir Mian Ambar Shah, also known as Umar Shah, arrived in the region by boat.[18] To facilitate his settlement and propagation, the emperor had a copperplate made designating Bajra as a tax-free settlement for him.[19] The word Bajra means large boat, being a corruption of bara-nauka, taking its name from Umar Shah's boat where the Pir initially lived in and preached to the locals.[20] Umar Shah also raised Amanullah and Thanaullah, the two sons of a local widow from Chhangaon. It was under Umar Shah's instructions that Amanullah established the Bajra Shahi Mosque and Thanaullah dug the 30-acre reservoir in front of the mosque. Construction began in 1715 CE and it was completed in 1741.[21] Another wali who migrated to the region to spread Islam was Pir Mir Ahmad Khandakar who settled in Babupur.[2]

Company rule[]

By 1756, the British East India Company had built weaving factories near the Feni River in Jagdia. Bhullooah came under British administration in 1765 and was made a part of the Bengal Presidency's Dacca Division. Sandwip and Feni were put under the administration of the Collector of Chittagong. By 1787, Bhulua became a district with its own Collector and Assistant Collector. Later that year, John Shore of Teignmouth ordered for Bhulua to be under the responsibility of the Collector of Mymensingh. When the District of Tippera (Comilla) was formed in 1790, the Noakhali mainland joined that district with Dandridge governing the Bhulua Pargana. Dandridge's office in Noakhali consisted of three years, in which he would have a bad relationship with the factory owners and salt agents. He was eventually replaced by Thompson before there was direct control by the Collector of Tippera.

In 1820, the Calaries Committee had a meeting to solve the problems that were prevalent in Bhulua between the factory owners, salt agents and collectors. Plowden, the Salt Agent of Noakhali, proposed that Bhulua be made its own district, with him being given the role as Collector of Bhulua. The Governor-General Francis Rawdon-Hastings accepted this recommendation in 1821. On 29 March 1822, Hastings passed an order in this regard and accordingly a new district was constituted with: South Shahbazpur, Sudharam, Begumganj, Ramganj, Raipur, Lakshmipur, Feni, Parshuram, Elahabad Pargana of Tippera and Hatia, Sandwip and Bamni of Chittagong district.

In the middle of the 19th century, Moulvi Imamuddin ushered an Islamic reformist movement in Noakhali akin to the Faraizi movement. This included abstaining from innovations such as the veneration of holy men.[2]

The advent of the British East India Company with its "exploitation and oppression" alongside zamindari subjugation, made life of the peasants and farmers difficult and despondent. A zamindar named Shamsher Gazi's exempted the peasants and became a powerful leader, later spreading his territory as far as Tripura.[22] Viewed as a "notorious plunderer" in the Tippera District, Noakhali and Chittagong areas,[23] he was later arrested by Mir Qasim by subterfuge for his excesses and put to death by a cannon

British Raj[]

Bhulua was constituted into the Chittagong Division in 1829, which it continues to be part of today. A large squad of Kukis from Hill Tippera entered the Chhagalnaiya plains (then in Tippera/Comilla) where they assassinated 185 British persons, kidnapped 100 of them and remained in the plains for one or two days. British troops and policemen were despatched to suppress them but the Kukis had already fled to the jungles of the princely state and they never returned ever again.[2]

The Bhulua district was renamed Noakhali in 1868. The following year, South Shahbazpur was given to Bakerganj District. The boundaries between Tippera and Noakhali were adjusted on 31 May 1875 in which Noakhali gained 43 villages and lost 22. In 1876, Noakhali district was divided into two sub-divisions; Sadar and Feni. Feni Sub-division was constituted with: Chhagalnaiya thana (formerly in Tippera/Comilla), Mirsharai thana (formerly in Chittagong), Feni Pargana, Parshuram and Sonagazi. In 1878, Mirsharai was given back to the Chittagong District. Another boundary adjustment took place in 1881, with the Feni River being made the dividing line between Noakhali and Chittagong districts, resulting in Noakhali gaining four villages.

In 1893, a cyclone heavily damaged half of the region's betel nut palms, in addition to the region's harvest. A large amount of cattle also drowned although not many human deaths occurred. The aftermath of the cyclone led to an outbreak of cholera which caused the betel nut palms to suffer from blight. This in turn killed thousands of Noakhaillas. Abnormally heavy rainfall occurred in 1896 which also caused havoc in the region and damaged crops. Regardless of these natural disasters, the annual birth rate of this region was much higher than the annual death rate; with a 23% increase in population from 1881 to 1891. The western parts of the region, places such as Ramganj Upazila, did not suffer as much from the cyclone though the blight had spread via the Meghna River.

In the 1901 census, the district's area was 1,644 sq mi (4,260 km2) and its population was about 1,141,728. The Bamni River drowned a large portion of Companiganj, which led to Jalia Kaibartas to migrate to Sandwip. The southern part of Sudharam also suffered from land loss, and a number of Chhagalnaiya residents began leaving their colonial homeland, subsequently migrating to Hill Tippera. A number of riverine islands (chars) emerged within the district borders, which also caused migration.[2] Sudharam had the most Muslims in the region, most likely due to it historically being the Mughal stronghold of the Noakhali region. Chhagalnaiya had the most Hindus, most likely due to it being under the Twipra Kingdom and only lately joining the colonial district.

Regional violence in 1946 escalated communal tensions throughout British India just before the 1947 partition. One of the worst religious massacres and incidents of ethnic cleansing against the Hindu community took place in Noakhali during the 1946 riot known as the Noakhali genocide. A huge number of mass killing, raping, looting, and forcible conversions took place. The prime minister of Bengal, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, answering a question from Dhirendranath Datta in the assembly early in 1947 stated that there had been 9,895 cases of forcible conversion in Tipperah alone. He said the number in Noakhali "ran into thousands".[24] It was not a random incident and was quite well planned, organised and directed by a few local political leaders.

Post-Partition of India[]

Sudharam/Noakhali town, the headquarters of Noakhali, vanished in the river-bed in 1951 as a result of erosion of the Meghna River. A new headquarters for the Noakhali District was then established at Maijdee. In 1964, Sadar Sub-division was divided into two sub-divisions namely Sadar and Lakshmipur.

During the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971, the Pakistan Army created the 39th ad hoc Division in mid-November, from the 14th Division units deployed in those areas, to hold on to the Comilla and Noakhali districts, and the 14th Division was tasked to defend the Sylhet and Brahmanbaria areas only.[25] About 75 Bengali freedom fighters were killed in Noakhali during a direct encounter with the Pakistan army on 15 June 1971, in front of the Sonapur Ahmadia School. Noakhali was liberated on 7 December 1971.[citation needed]

In 1984, the District of Noakhali was further divided into three districts for administrative convenience; Noakhali District, Lakshmipur and Feni. As a result of partition, the withdrawal of Feni River Water became a source of conflict between Bangladesh and the Republic of India.

References[]

- ^ "View of Noakhali (Bengal)". The British Library.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Webster, John Edward (1911). Eastern Bengal and Assam District Gazetteers. 4. Noakhali. Allahabad: The Pioneer Press.

- ^ Islam, Shariful (2012). "Bangla Script". In Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ AKM Shanawaz (2012). "Inscriptions". In Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ishaque, Muhammad, ed. (1977). Bangladesh District Gazetteers. Noakhali. Government of Bangladesh.

- ^ Mitra, Naliniranjan (1965). "ইলাহাবাদ ও দাঁদরা পরগণা". নোয়াখালির ইতিকথা [The Story of Noakhali] (in Bengali).

- ^ Sen, Pyarimohan. নোয়াখালীর ইতিহাস (in Bengali). pp. 18 and 52.

- ^ Mawlana Nur Muhammad Azmi. "2.2 বঙ্গে এলমে হাদীছ" [2.2 Knowledge of Hadith in Bengal]. হাদীছের তত্ত্ব ও ইতিহাস [Information and history of Hadith] (in Bengali). Emdadia Library. p. 24.

- ^ Choudhury, Achyut Charan (1917). (in Bengali) (first ed.). Kolkata: Kotha. p. 46 – via Wikisource.

- ^ Islami Bishwakosh. 14. Islamic Foundation Bangladesh. 1986. p. 238.

- ^ Jarrett, Henry Sullivan. Sarkar, Jadunath (ed.). The Ain I Akbari of Abul Fazl 'Allami (Vol 2). Bibliotheca Indica. p. 128.

- ^ Hasan, Perween (2007). Sultans and Mosques: The Early Muslim Architecture of Bangladesh. I.B. Tauris. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-84511-381-0.

It was only in 1612, during the reign of Jahangir, that all of Bengal was firmly integrated as a Mughal province and was administered by viceroys appointed by Delhi.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c M. I. Borah (1936). Baharistan-I-Ghaybi – Volume II.

- ^ Population Census of Noakhali. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, Statistics Division, Ministry of Planning. 1974. p. 12.

- ^ "3. The Feringhees of Chittagong". The Calcutta Review. 53. University of Calcutta. 1871. p. 74.

- ^ M Noorul Haq (1977). বৃহত্তর চট্টলা. p. 66.

- ^ Ghulam Husain Salim (1902–1904). Riyazu-s-salatin; a history of Bengal. Translated from the original Persian by Maulavi Abdus Salam. Calcutta Asiatic Society. pp. 230–231.

- ^ Thompson, W. H. (1919). "24". Final Report on the Survey and Settlement Operations in the District of Noakhali, 1914–1919. Calcutta: Bengal Secretariat Book Depot. pp. 60–61.

- ^ Eaton, Richard M (1993). "Bengal under the Mughals: Islam and the Agrarian Order in the East: Charismatic Pioneers on the Agrarian Frontier". The rise of Islam and the Bengal frontier, 1204-1760. University of California Press. p. 211.

- ^ Muhammad Badrur Huda, additional subdivisional officer, Revenue, Noakhali District Collectorate, 17 June 1982

- ^ Hasan, Dr Syed Mahmudul (1971). Muslim Monuments of Bangladesh. p. 101.

- ^ Rāẏa, Suprakāśa (1999). Peasant Revolts And Democratic Struggles In India. ICBS (Delhi). p. 24. ISBN 978-81-85971-61-2. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ Sharma, Suresh Kant; Sharma, Usha (2005). Discovery of North-East India: Geography, History, Culture, Religion, Politics, Sociology, Science, Education and Economy. Tripura. Volume eleven. Mittal Publications. p. 24. ISBN 978-81-8324-045-1. Retrieved 29 October 2015.

- ^ Batabyal, Rakesh (2005). Communalism in Bengal: From Famine to Noakhali, 1943–47. New Delhi: Sage Publications. p. 282. ISBN 81-7829-471-0.

H.S. Suhrawardy, the chief minister, while answering the question of Dhirendra Nath Dutt on the floor of the Bengal Legislative Assembly, gave a figure of 9,895 cases of forcible conversion in Tippera, while that for Noakhali was not known 'but (which) ran into thousands'.

- ^ Salik, Siddiq, Witness to Surrender, pp126

Further reading[]

- Eaton, Richard The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760 (University of California Press, 1993)

- Noakhali District

- Feni District

- Lakshmipur District

- History of Chittagong Division

- History of Bangladesh

- History of Noakhali