History of the Second Avenue Subway

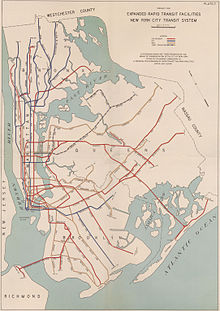

The Second Avenue Subway, a New York City Subway line that runs under Second Avenue on the East Side of Manhattan, has been proposed since 1920. The first phase of the line, consisting of three stations on the Upper East Side, started construction in 2007 and opened in 2017, ninety-seven years after the route was first proposed. Up until the 1960s, many distinct plans for the Second Avenue subway line were never carried out, though small segments were built in the 1970s. The complex reasons for these delays are why the line is sometimes called "the line that time forgot".

The line was originally proposed in 1920 as part of a massive expansion of what would become the Independent Subway System (IND). The Great Depression crushed the original proposal, and lack of funds scuttled numerous revivals throughout the 20th century. Meanwhile, the elevated lines along Second Avenue and Third Avenue, which the Second Avenue Line was intended to replace, were respectively demolished in 1942 and 1955, leaving the Lexington Avenue Subway as the only rapid transit line on much of Manhattan's east side. By the time the Second Avenue Line was built, the Lexington Avenue Line was by far the busiest subway line in the United States, with an estimated 1.3 million daily riders in 2015.

Construction on the Second Avenue Line initially began in 1972 as part of the Program for Action, but was halted in 1975 because of the city's fiscal crisis, with only a few short segments of tunnels having been completed. Meanwhile, construction of the 63rd Street Lines, which would connect the Second Avenue Line and the IND Queens Boulevard Line to the BMT Broadway Line and the IND Sixth Avenue Line, began in 1969. The first segment of the 63rd Street Lines, which opened on October 29, 1989, included provisions for future connections to the Second Avenue Line.

Work on the line restarted in 2007 following the development of a financially secure construction plan. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) awarded a tunneling contract for the first phase of the project to the consortium of Schiavone/Shea/Skanska (S3) on March 20, 2007. This followed preliminary engineering and a final tunnel design completed by a joint venture between AECOM and Arup. Parsons Brinckerhoff served as the Construction Manager of the project. A full funding grant agreement with the Federal Transit Administration for the first phase of the project was received in November 2007. A ceremonial ground-breaking for the Second Avenue Subway was held on April 12, 2007. The first phase of the line, consisting of three newly built stations and two miles (3.2 km) of tunnel, cost $4.45 billion. A 1.5-mile (2.4 km), $6 billion second phase is in planning.

1920–1941: Initial planning[]

After World War I, the New York City Subway experienced a surge in ridership. By 1920, 1.3 billion annual passengers were riding the subway, compared to 523 million annual riders just seven years before the war. The same year, the New York Public Service Commission launched a study at the behest of engineer Daniel L. Turner to determine what improvements were needed in the city's public transport system.[1][2] Turner's final paper, titled Proposed Comprehensive Rapid Transit System, was a massive plan calling for new routes under almost every north-south Manhattan avenue, extensions to lines in Brooklyn and Queens, and several crossings of the Narrows to Staten Island.[1][3]: 11–18, map at back cover Massively scaled-down versions of some of Turner's plans were found in proposals for the new city-owned Independent Subway System (IND).[4] Among the plans was a massive trunk line under Second Avenue consisting of at least six tracks and numerous branches throughout Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx.[3] Turner also proposed that the two elevated lines be knocked down to make room for the 6-track Second Avenue Subway.[5]: 203 The plan was to connect the new line to the then-unbuilt Sixth Avenue and Eighth Avenue subway lines.[6] A proposal for a Third Avenue subway was also put forth,[7] as was another one for a First Avenue Subway.[8] However, in the initial version of the plan, an East Side subway was not prioritized as part of the IND's construction, regardless of whether it was under First, Second, or Third Avenues.[5]: 203

In January 1927, Turner submitted a revised proposal. It was now going to connect to a Tenth Avenue trunk line as well as to crosstown lines in the Bronx and Queens. The Second Avenue Subway was still a six-track line through Manhattan, except for a short eight-track tunnel at its junction with the Queens lines. The plan called for a connection to the IND Concourse Line in the Bronx, as well as another one to the IND Fulton Street Line in Brooklyn. Such a plan would have cost $165,000,000 (equivalent to $2,458,000,000 in 2020), including connections and underwater crossings. As the IRT Lexington Avenue Line got more crowded, some suggested ideas that were considered unusual. One suggestion included a new tunnel under Lexington Avenue, while another included a tunnel under a separate right-of-way between Second and Third Avenue.[6]

On September 16, 1929, the Board of Transportation of the City of New York (BOT) tentatively approved the expansion,[2][4] which included a Second Avenue Line with a projected construction cost of $98,900,000 (equivalent to $1,477,000,000 in 2020), not counting land acquisition.[9] From north to south, the 1929 plan included four tracks from the Harlem River (where it would continue north as a Bronx trunk line with several branches) to 125th Street, six tracks from 125th Street to a link with the Sixth Avenue Line at 61st Street, four tracks from 61st Street to Chambers Street, and two tracks from Chambers Street to Pine Street.[10]: B-2 The plan was soon modified with the addition of another Bronx branch, as well as an extension of the subway to Water and Wall Streets.[5]: 203 At the time, it was supposed to be completed between 1938 and 1941.[9] In anticipation of the line's opening, real estate prices along the proposed route rose by an average of 50%.[11] There were high demand for tenements along the route of the proposed subway,[12] and sites located at street corners along the route were quickly bought up.[13]

Due to the Great Depression, the soaring costs of the expansion became unmanageable. Construction on the first phase of the IND was already behind schedule, and the city and state were no longer able to provide funding. By 1930, the line was shortened to between 125th and 34th Streets, with a turnoff at 34th Street and a crosstown connection there; this line was to be complete by 1948.[9] The line above 32nd Street was to start construction in 1931, with construction of a southern extension to Houston Street to commence in 1935; these segments would open in 1937 and 1940, respectively.[14] By 1932, the Board of Transportation had modified the plan to further reduce costs, omitting a branch in the Bronx, and truncating the line's southern terminus to the Nassau Street Loop.[5]: 204–205

Further revision of the plan and more studies followed. By 1939, construction had been postponed indefinitely, and the Second Avenue Line was relegated to "proposed" status. The Board of Transportation had ranked it as the city's 14th most important transportation project.[6] The Second Avenue Line was also cut to two tracks, but now had a connection to the BMT Broadway Line. The reduced plan now had a single northern branch through Throggs Neck, Bronx, and a branch south into Brooklyn, connecting to a stub of the IND Fulton Street Line at the Court Street station, which is now the site of the New York Transit Museum.[5]: 205 The subway's projected cost went up to US$249 million (equivalent to $4,381,000,000 in 2020). The United States' entry into World War II in 1941 halted all but the most urgent public works projects, delaying the Second Avenue Line once again.[9]

1940s–1950s: After World War II[]

As part of the unification of the three subway companies that comprised the New York City Subway in 1940, elevated lines were being shut down all over the city and replaced by subways, continuing the IND's trend of phasing out elevated lines and streetcars in favor of new subways. For example, the IND Sixth Avenue Line replaced the Sixth Avenue Elevated, while the IND Fulton Street Line replaced the Fulton Street Elevated. Demolition of the elevateds also had the perceived effect of revitalizing the neighborhoods that they traveled through.[5]: 205–206 [16]: 106 The northern half of the Second Avenue Elevated, serving the Upper East Side and East Harlem, closed on June 11, 1940; the southern half, running through Lower Manhattan, East Midtown and across the Queensboro Bridge to Queens, closed on June 13, 1942.[2][15][17] The demolition of the Second Avenue elevated caused overcrowding on the Astoria and Flushing Lines in Queens, which no longer had direct service to Manhattan's far East Side.[5]: 208 Because of the elevated line's closure, as well as a corresponding increase in the East Side's population, the need for a Second Avenue subway increased.[18][19]

In 1944, Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia announced that work on the Second Avenue subway line was progressing.[5]: 209 The same year, BOT superintendent Philip E. Pheifer came up with a map of train frequencies for the line, with about 56 trains per hour projected to go through the Second Avenue line. Pheifer also put forth a proposal for Second Avenue Subway services, which would branch extensively off to B Division lines, including the IND Sixth Avenue Line, BMT Broadway Line, and BMT Nassau Street Line, via pre-existing BMT trackage over the Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges.[6][5]: 209–210 From Canal Street to 57th Street the line was to be four tracks, with six tracks north of 57th Street. South of Canal Street there would be two tracks.[10] The subway was to be opened by 1951.[9] In addition, a new Bronx Branch would replace the Third Avenue El in the Bronx.[6] By 1945, though, plans for the Second Avenue Subway were again revised. The southern two-track portion was abandoned as a possible future plan for connecting the line to Brooklyn, while a Bronx route to Throggs Neck was put forth.[5]: 210–211

Under Mayor William O'Dwyer and General Charles P. Gross, another plan was put forth in 1947 by Colonel Sidney H. Bingham, a city planner and former Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) engineer. O'Dwyer and Gross believed that construction of a Second Avenue subway line would be vital to both increasing capacity on existing lines and allowing new branch lines to be built.[6][5]: 209 This plan would again connect the Second Avenue Line to Brooklyn. As with Pheifer's proposal, a train frequency map was created; however, Bingham's proposal involved more branch lines and track connections. A connection to Brooklyn was to be made via the Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridge, and would allow trains from these bridges to go onto the Sixth Avenue Line or the Second Avenue Line. Other connections to the Second Avenue Line were to be provided at 57th Street, via a line connecting to the Sixth Avenue Line; two express tracks would be built along that line north of West Fourth Street. The IRT Pelham Line would be switched to the combined IND/BMT division (this plan also includes other connections, which have been built), and connected to the Second Avenue Line. The Second Avenue Line would end just north of that connection, at 149th Street, with transfers to the IRT White Plains Road Line and the elevated IRT Third Avenue Line, the latter of which would be demolished south of 149th Street.[6][5]: 209 [20] There would also be a connection to the IND Concourse Line.[6] The line was to be built in sections. The Manhattan section was top-priority, but the Brooklyn section was 19th on the priority list, and the Bronx section did not have a specific priority.[5]: 209

By the next year, New York City had budget shortfalls. The city was short of $145 million (in 1948 dollars) that were needed for rehabilitation and proposed capital improvements, which cost a total of $800 million. The city petitioned the New York State Legislature to exceed its $655 million debt ceiling so that the city could spend $500 million on subway construction, but this request was denied.[6]

The New York Board of Transportation ordered ten new prototype subway cars made of stainless steel from the Budd Company. These R11 cars, so called because of their contract number, were delivered in 1949 and specifically intended for the Second Avenue Subway. They cost US$100,000 (equivalent to $1,000,000 in 2020) each; the train became known as the "million dollar train".[21] The cars featured porthole style round windows and a new public address system. Reflecting public health concerns of the day, especially regarding polio, the R11 cars were equipped with electrostatic air filters and ultraviolet lamps in their ventilation systems to kill germs.[21]

In 1949, Queens and Lower Manhattan residents complained that the Second Avenue Subway would not create better transit options for them.[6] A year later, revised plans called for a connection from Second Avenue at 76th Street to Queens, under 34th Avenue and Northern Boulevard, via a new tunnel under the East River. Connections would also be made to the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR)'s Rockaway Beach Branch.[6][20][note 2] New York voters approved a bond measure for its construction in 1951, and the city was barely able to raise the requisite $559 million for the construction effort. However, the onset of the Korean War caused soaring prices for construction materials and saw the beginning of massive inflation.[6][9][23] Money from the 1951 bond measure was diverted to buy new cars, lengthen platforms, and maintain other parts of the aging New York City Subway system.[20][24] Out of a half-billion-dollar bond measure, only $112 million (equivalent to $1,117,000,000 in 2020), or 22% of the original amount, went toward the Second Avenue Subway.[6][9][24] By then, construction was due to start by either 1952 or 1957, with estimated completion by 1958 at the earliest.[9] Because many people thought that the bonds were solely to be used on the new subway, many people accused the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA) of misusing the bonds.[6]

By January 1955, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey and the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority could theoretically raise $1.25 billion effective immediately (equivalent to $12,076,000,000 in 2020). In his 1974 book The Power Broker, Robert A. Caro estimated that this amount of money could modernize both the Long Island Rail Road for $700 million and the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad for $500 million, with money left over to build the Second Avenue Subway as well as proposed extensions of subway lines in Queens and Brooklyn.[25]: 928–929 However, Robert Moses, the city's chief urban planner at the time, did not allow funding for most mass transit expansions in the New York City area,[25]: 930–933 instead building highways and parkways without any provisions for mass transit lines in the future.[25]: 939–958 Caro noted that the lack of attention to mass transit expansions like the Second Avenue Subway contributed to the decline of the subway: "When Robert Moses came to power in New York in 1934, the city’s mass transportation system was probably the best in the world. When he left power in 1968 it was quite possibly the worst."[25]: 933

A block to the west of the proposed subway line, the Manhattan section of the Third Avenue Elevated, the only other elevated line in the area, closed on May 13, 1955,[26] and was demolished in 1956.[2][15][16]: 106–107 Contrary to what many East Side residents thought, the demolition of the elevateds did not help the travel situation, as the Lexington Avenue Line was now the only subway transportation option on the East Side, leading to overcrowding.[6]

By 1957, it had become clear that the 1951 bond issue was not going to be able to pay for the Second Avenue Line. The money had been used for other projects, such as the integration of the IRT Dyre Avenue Line, and IND Rockaway Line and reconfiguration of the DeKalb Avenue Interlocking.[5]: 216 [24] By then, the New York Times despaired of the line's ever being built.[9] "It certainly will cost more than $500 million and will require a new bond issue," wrote one reporter.[24] In March of that year, NYCTA chairman Charles L. Patterson stated that the NYCTA had used the bond funds properly and that the bonds were not dedicated solely to fund the Second Avenue Line. He stated that the bonds had been allocated to the corridor based on increasing ridership on the Second Avenue Line, but admitted that currency inflation, as well as necessary rehabilitation work to the existing lines, made the Second Avenue Line unlikely in the near future.[6] Despite the lack of funding and declining ridership, the city government still believed the Second Avenue Line to be a priority, with the New York City Planning Commission expressing support for the line in a 1963 report.[16]: 107

1960s: New plans[]

As the early 1960s progressed, the East Side experienced an increase in development, and the Lexington Avenue Line became overcrowded.[6] In 1962, construction began on a connection between the Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges and the Sixth Avenue Line. This segment, the Chrystie Street Connection, was first proposed in the 1947 plan as the southern end of the Second Avenue line, which would feed into the two bridges. When opened on November 26, 1967, the connection included the new Grand Street station on the Sixth Avenue Line (another station, 57th Street, opened on July 1, 1968), and introduced the most significant service changes ever carried out in the subway's history.[5]: 216–217 Grand Street, located under Chrystie Street (the southern end of Second Avenue) was designed to include cross-platform transfers between the Sixth Avenue and Second Avenue Lines.[5][27][28]

Plans approved[]

In 1964, Congress passed the Urban Mass Transportation Act, promising federal money to fund mass transit projects in America's cities via the Urban Mass Transportation Administration (UMTA).[6][29] Three years later, voters approved a $2.5 billion (worth about $19,404,000,000 in current dollars) Transportation Bond Issue, which provided over $600 million (worth $4,657,000,000 today) for New York City projects, including for a 1968 Program for Action.[2][6][30] The Second Avenue project, for a line from 34th Street to the Bronx, was given top priority.[9] The City secured a $25 million UMTA grant for initial construction.[5]: 219 [9] On March 19, 1970, the Board of Estimate approved Route 132-C, which was the portion of the line south of 34th Street.[31]: 135 Mayor John Lindsay, on August 16, 1970, announced the approval of a $11.6 million design contract for the line, which was awarded to DeLeuw, Cather & Company.[32] Second Avenue was chosen for a subway line over First Avenue because it was closer to places of employment than First Avenue.[33]: 27 Construction of the entire line was seen as conducive to revitalizing New York City's then-declining economy, and the line was a big component of the 1969 "Plan for New York City" proposal.[34]

Route 132-A[]

The Program for Action proposed a Second Avenue line to be built in three phases. The first phase, officially Route 132-A,[35] would have run between 34th Street in Midtown and 126th Street under Second Avenue. This section was expected to cost $381 million (equal to about $2,435,000,000 today).[33]: 1 The line would have included stops at Kips Bay (34th Street), United Nations (between 44th Street and 48th Street), Midtown East (57th Street), Yorkville (86th Street), Franklin Plaza (106th Street), and Triboro Plaza (125th Street).[10][36][37][33]: 4 The 48th Street stop would connect to a planned Metropolitan Transportation Center at Third Avenue and 48th Street, which would contain a new east side terminal for the Long Island Rail Road. The line included older proposals for connections to the Sixth Avenue and Broadway lines in Midtown via a new crosstown line, which would now be located on 63rd Street.[36] The 63rd Street Line would also include a connection allowing Second Avenue line trains to run to Queens, which would have been used in revenue service. Between 72nd Street and 48th Street there were going to be four tracks to provide more efficient service.[33]: 3, 5

The entirety of the 4.7 miles (7.6 km)-long Route 132-A was to be constructed underground through tunneling and cut-and-cover. Station mezzanines; the line north of 92nd Street, where the rock profile drops away sharply; and the area around 48th Street, where there is a crevice in the rock profile, would be constructed using cut-and-cover. The temporary decking of Second Avenue was required for this construction to take place and to allow for traffic aboveground to proceed. The remaining portions of the line were to be built through tunneling. Only one business relocation was planned for the construction of the line. A gas station at the southeast corner of 63rd Street and Second Avenue was to be relocated as the site needed to be used for a construction and ventilation shaft, in addition to being used for a permanent ventilation superstructure. Underground easements were to be required under thirteen properties in the vicinity of 63rd Street.[33]: Appendix A 3, 4 Compared to other subway lines, the Second Avenue line was going to be much quieter.[33]: 14

Route 132-B[]

The line's second phase, Route 132-B would have extended it north from East 126th Street to East 180th Street in the Bronx. Second Avenue line trains would use a new express bypass line along East 138th Street, and the former tracks of the New York, Westchester and Boston Railway (NYW&B) near the Bruckner Expressway.[36] In Hunts Point, service would split into two branches. One branch would continue to use former NYW&B trackage to East 180th Street, at which point the line would connect to the IRT Dyre Avenue Line. A second branch would connect to the IRT Pelham Line in the vicinity of Whitlock Avenue station, another element from earlier plans. The first branch would take over all service on the Dyre Avenue Line, offering cross-platform transfers to IRT White Plains Road Line trains at East 180th Street station, which would also be reconfigured. The second branch would take over service on the upper portion of the Pelham Line, between Whitlock Avenue and Pelham Bay Park. All stations on the Dyre Avenue and upper Pelham Lines would have platforms shaved back to accommodate larger B Division trains.[10][36][33]: 5, Appendix A 2 There were 140,000 daily passengers expected on the Second Avenue line at 64th Street, reducing the number of passengers on the Lexington Avenue Line from 287,000 passengers at 64th Street to 171,000.[33]: Appendix B and C

As part of the approved plan, in the Bronx, the line would have run along East 138th Street, with a cross-platform transfer to Lexington Avenue Line trains at Brook Avenue on the IRT Pelham Line, which would have been reconfigured. A study was undertaken to determine whether an alternative route would reduce costs. Adoption of the alternate route would have required a new Route and General Plan. As part of the alternative plan, this transfer station was eliminated from the plan due to high environmental problems and high costs. Instead, the line would diverge from the original route from a location 150 feet (46 m) north of the Harlem River bulkhead, would swing eastward, passing through the Willis Avenue Bridge piers, underneath the Penn Central's Harlem River Yard and between the Triboro Bridge piers. Then the line would head north, entering an open cut, before using two unused tracks in the vicinity of Willow Avenue and East 132nd Street, using the Penn Central's bridges and embankments to return to the original route at East 141st Street. Running in a tunnel would remove potential conflicts with the rail yard and would have allowed the rail yard to be redeveloped.[38]

This alternative was found to cost $117 million (equal to about $563,000,000 today), compared to the original plan, which would have cost $240 million (equal to about $1,154,000,000 today). The original route would have displaced five commercial properties while the alternative would have required the relocation of tracks and warehouse platforms in the yard. The downside of the alternative was that it would not provide a transfer in the South Bronx between the Pelham Line and the Second Avenue Line, preventing Second Avenue passengers from directly accessing Pelham Line stations between Brook Avenue and Longwood Avenue. The alternate route reduced environmental impacts since it was to be constructed through the rail yard, as opposed to under East 138th Street.[38]

Also during this phase, service on the upper Pelham Line would be extended to Co-op City, Bronx. A third branch of the Second Avenue line to replace the Third Avenue El in the Bronx would also be built, running adjacent to the right-of-way of Metro-North's Harlem Line on Park Avenue.[34]

Route 132-C[]

The line's final phase, Route 132-C, would have extended the Second Avenue line south from 34th Street in Midtown to Lower Manhattan, and would have been 3.7 miles (6.0 km) long. This section was expected to cost $393 million (equal to about $2,291,000,000 today). A majority of the section, 12,400 feet (3,800 m), would be constructed using cut-and-cover, with the remainder, 6,700 feet (2,000 m) using tunnel boring machines. Tunnel boring machines were to have been employed to construct the sections between East 32nd Street and East 7th Street, and Wall Street and Whitehall Street. The alignment for this portion of the line would have been via Second Avenue, Chrystie Street, Chatham Square, Saint James Place, and Water Street to the terminal near Water Street and Whitehall Street. The line would have consisted of two tracks, with layup tracks to insure operational reliability.[39] Pine-Wall and Whitehall Street stations would both have four tracks (two platform levels with two tracks each) in order to increase the capacity of the Whitehall Street terminal above 30 trains per hour to 40 trains per hour, and to improve passenger flow.[36] One platform would be used for Queens-bound service, while the other would be for Bronx-bound service. The 14th Street station would have had three tracks on a single level to facilitate access to and from the 615 feet (187 m)-long pit track located to the north of the station.[40][36]

The seven stations on the line would have been East 23rd Street (between East 23rd Street and East 27th Street), East 14th Street (between East 13th Street to East 15th Street), East Houston Street (at the intersection of East Houston Street with Chrystie Street and Second Avenue), Grand Street (enlarging the existing station), Chatham Square (under Chatham Square at the intersection of East Broadway, the Bowery, Park Row and St. James Place), Pine–Wall (under Water Street from Wall Street to John Street) and Whitehall Street (under Water Street from Whitehall Street to Coenties Slip).[10][39][40] Free transfers would be offered to existing lines at 14th Street, East Houston Street and Whitehall Street, while Grand Street would be reconstructed. The East Houston Street station would have used the existing provisions located within the mezzanine of the Second Avenue station on the IND Sixth Avenue Line.[36] During construction, a portion of Sara D. Roosevelt Park at Chrystie Street would have been used for the line's construction.[39]

All stations would have included escalators, high intensity lighting, improved audio systems, platform edge strips, and non-slip floors to accommodate the needs of the elderly and people with disabilities, but no elevators. Space at each station would have been used for ancillary facilities.[39] The stations were to be made with brick walls and pavers alongside stainless steel, and would have relatively small dimensions, with 10-foot (3.0 m) mezzanine ceilings. Design contracts were awarded for several stations. Morris Ketchum Jr. & Associates were given the design contract for Chatham Square; Haines, Lundberg & Waehler for Grand Street; Poor & Swanke & Partners for 23rd Street; Harrison & Abramovitz for 48th Street; I. M. Pei & Associates for 57th Street; Carson, Lundin & Thorsen for 72nd Street; Gruzen & Partners for 86th Street; Damaz & Weigel for 96th Street; and Johnson & Hanchard for 106th Street.[16]: 110

Station location controversy[]

The line's planned stops in Manhattan, spaced farther apart than those on existing subway lines, proved controversial, especially as the line would only have three stations in the borough north of 63rd Street.[16]: 107 [41]: 37 The Second Avenue line was criticized as a "rich man's express, circumventing the Lower East Side with its complexes of high-rise low- and middle-income housing and slums in favor of a silk stocking route.”[5]: 218 In order to cut down on walking distance, the stations would have been up to four blocks long. The plan for stations was reluctantly disclosed by the NYCTA on August 27, 1970 after a meeting with Assemblyman Stephen Hansen, who represented an area that covered the Upper East Side. Justifying the lack of stations, the NYCTA's chief engineer John O'Neil said that a station on the line cost $8 million which made it prohibitively expensive to build more. The stations at 34th Street and 125th Street were decided as they would be the terminal points, and the 48th Street location was decided because of a transfer to a proposed people mover that would take riders to other subway lines and the West Side.[42]: 37 57th Street was decided because of the large volume of crosstown traffic, and 86th Street had been decided upon because of the large number of high-rise buildings and stores in the area. These two stations and 106th Street were decided upon in a planning report.[37]

People protested for almost a year over the lack of stations at 72nd and 96th Streets.[43] In September 1970, MTA Chairman William Ronan promised to host meetings with members of communities along the Second Avenue subway's route.[44] On August 27, 1971, a new plan for the line was unveiled with a Lenox Hill (72nd Street) station and an extension of the 48th Street station southward almost to 42nd Street.[43] The 96th Street station was still not in the official plans, despite the proximity of the Metropolitan Hospital Center to the proposed station.[5]: 220 [43] In late 1971, in response to public outcry, the MTA announced the addition of a station at 96th Street,[45]: 2 [46] at a cost of $10 million.[45]: 2 In the 1971 plan, several stations were stretched to give riders the impression that they were already in the station, while they would have to walk long distances in underground passages to reach the trains.[42]: 37

The line's planned route on Second Avenue, Chrystie Street and the Bowery in the Lower East Side also drew criticism from citizens and officials.[47] In January 1970, the MTA issued a plan for a spur line, called the "cuphandle", to serve the heart of the Lower East Side. Branching off from the IND Sixth Avenue Line near the Second Avenue station, the spur would run east on Houston Street, turn north on Avenue C, and turn west on 14th Street, connecting to the BMT Canarsie Line.[16]: 107 [47] The subway soon became a political bargaining chip. Elected officials from Manhattan Community Board 8 protested the lack of stations in East Harlem. When politicians from the Lower East Side started advocating for the $55 million (worth about $351,000,000 in current dollars) Avenue C cuphandle, which would have served nearly 50,000 people, Queens politicians stated that the money would be better used to reactivate the abandoned Rockaway Beach Branch, which would cost only $45 million (equal to about $288,000,000 today) and would serve over 300,000 people.[41]: 38

On March 19, 1970, the Board of Estimate approved the connecting loop through the Lower East Side. The route was a compromise; a year earlier the board vetoed the Second Avenue Line proposal, and instead proposed that the main line go eastward from East 17th Street onto Avenue A and then curve onto the regular route at Chatham Square. The NYCTA said that it would cost $55 million more than a direct line and the transfer at Grand Street would have been lost. In addition, less riders would have been diverted from the Lexington Avenue Line under this scheme.[48] Two services were planned to use the loop. Some trains from the IND Sixth Avenue Line would join the loop at Houston Street and Second Avenue and then swing around to 14th Street and Eighth Avenue. There would also have been a shuttle between those two stations.[49]

By 1971, officials had still not confirmed any of the line's stations. The MTA was planning to only add thirteen stops along the line in Manhattan, with six of these above 34th Street; by comparison, the parallel Lexington Avenue Line had 23 stops in Manhattan, of which twelve were above 33rd Street. The reasoning behind this was to give faster service to riders from the Bronx and Queens, from where trains would funnel into either the new Second Avenue mainline or the existing Sixth Avenue and Broadway Lines.[41]: 37 Disagreements over the number and location of stations were still ongoing, with New York Magazine advising readers to "get community support" if they wanted a station to be built in their vicinity.[41]: 38 The dispute over the Second Avenue Subway applied between several disparate groups. Those arguing included residents of the Bronx and Queens who had poor infrastructure compared to residents of Manhattan and Brooklyn; the generally affluent residents of the Upper East Side; the ethnically diverse communities of lower Manhattan and East Harlem; the financial companies in Lower Manhattan; technical workers; the government of New York City; and the city's Board of Estimate.[41]: 37

1970s: Original construction efforts[]

Construction starts[]

Despite the controversy over the number of stops and routes, a combination of Federal and State funding was obtained. In March 1972, the entire cost of the section between 34th Street and 126th Street, according to the projects Draft Environmental Study, was estimated to be $381 million.[33]: 1 In June 1972, it was announced that UMTA would grant $25 million for the construction of this section of the line. The MTA had requested $254 million in federal funds for the northern part of the line. Preliminary estimates of the cost of the southern portion of the line came to $450 million.[50] The entire section was to be constructed using the cut-and-cover method of subway construction, in which a trench is dug beneath the street and then covered. 14,300 square yards of decking were to have been used to cover the trench, allowing for traffic on Second Avenue to not be interrupted. The entire line from Water Street to 180th Street in the Bronx was expected to be completed by 1980.[16]: 107, 110 [35]

On September 13, 1972, construction work on Section 11 of Route 132-A, the section between 99th Street and 105th Street, went up for bid, and Slattery Associates of Maspeth, Queens got the low bid of $17,480,266.[35] The MTA board approved the award on September 22, 1972.[31]: 137 A groundbreaking ceremony was held on October 27, 1972 at Second Avenue and 103rd Street.[10][51][52] Construction began shortly thereafter on the segment.[16]: 110 [53] Work on the initial segment was slowed down due to a network of uncharted utility lines below the street. The utilities, as part of the construction, were to be relocated under the sidewalks. Old footings from the Second Avenue Elevated were found while the section was excavated.[54] Another problem in the construction of this segment was the large amount of ground water, which put enormous pressure on the tunnel. An underground substation was constructed at 105th Street, and five feet of concrete had to be poured for the floor so that the structure would not float in the muck.[55] This section is 1,815 feet (553 m) long.[18]: 9D-24

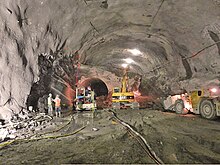

Construction costs for the entire line were pegged at $1 billion (about $6.187 billion today), and rose to $1.3 billion (about $7.579 billion today) a year later.[9] In December 1972, the NYCTA started soliciting bids for the construction of Section 13 of Route 132-A, which was between 110th and 120th Streets in East Harlem.[56]: 512 Bids opened on January 26, 1973, and the bid from Cayuga-Crimmins was the lowest of six bids. The contract was awarded on March 20, 1973, and, in that month, construction of the segment by Cayuga-Crimmins began at a cost of $35.45 million (equivalent to $219,327,000 in 2020).[53][56]: 555–556 [57] About half of this section was constructed through solid rock and therefore continual blasting was necessary. One worker was killed in the construction of this section.[55] This section is 2,556 feet (779 m) long.[18]: 9D-24

On October 25, 1973, the line's Chinatown segment, section 132-C5, commenced construction at Canal Street under the foot of the Manhattan Bridge.[16]: 110 [53] This segment, between Canal and Division Streets, was due to be completed by 1980 and was being built at a cost of $8.3 million (equal to about $48,388,000 in current dollars).[53] The segment, which is 738 feet (225 m) long, was constructed by the Horn–Kiewit Construction Company.[18]: 9D-24 [57] In January 1974, a contract, D-21308, was put out for the construction of Section 7 of Route 132-C, which spanned an area between 2nd Street and 9th Street in the East Village. Slattery Associates was awarded the contract in March 1974 with a low bid of $21,346,310 (equal to about $112,018,000 in current dollars). The job was expected to be completed in 39 months.[58] On July 25, 1974, construction on the segment was started near Second Street.[57][59]: 160 Another contract, for a Midtown segment between 50th and 54th Streets, was awarded that year for $34.6 million, with constructed expected to begin in the fall. However, construction never commenced.[57] In total, construction on the Second Avenue Line during the 1970s spanned over 27 blocks.[52][53][57]

The city also changed zoning regulations for areas located near planned stations, being first proposed on September 30, 1974 by Mayor Beame. New and existing buildings in these areas were required to build pedestrian plazas and arcades that would allow for the future construction of subway entrances.[5]: 222 Permanent special transit use districts were created within 100 feet of the proposed stations.[16]: 110 [60] The line was designed so that Second Avenue could be widened at a later date by narrowing the sidewalks by five feet on either side of the street.[61]

Construction halts[]

In spite of the optimistic outlook for the Second Avenue line's construction, the subway had seen a 40% decrease in ridership since 1947, and its decline was symptomatic of the downfall of the city as a whole. A $200 million subsidy for the MTA, as well as a 1972 fare increase from 30 cents to 35 cents, was not enough to pay for basic upkeep for the subway system, let alone fund massive expansion projects like the Second Avenue Subway.[62]: 52 In 1971, the subway had been proposed for completion by 1980,[41]: 38 but just two years later, its completion date was forecast as 2000.[62]: 52 Furthermore, voters had rejected a bond issue in 1971 that would have allocated $150 million for the line's southern portion. By the mid-1970s, a growing proportion of the public was advocating for the MTA to focus on existing maintenance, even as officials publicly expressed hope that some other source of funding would materialize for the Second Avenue Subway.[53]: 110, 112

The city soon experienced its most dire fiscal crisis yet, due to the stagnant economy of the early 1970s, combined with the massive outflow of city residents to the suburbs.[51] In October 1974, the MTA chairman, David Yunich, announced that the completion of the line north of 42nd Street was pushed back to 1983 and the portion to the south in 1988.[63] On December 13, 1974, New York City mayor Abraham Beame proposed a six-year transit construction program that would reallocate $5.1 billion of funding from the Second Avenue Line to complete new lines in Queens and to modernize the existing infrastructure, which was rapidly deteriorating and in dire need of repair.[55] The plan also used Federal aid to stabilize the transit fare.[64] On December 22, 1974, the Regional Plan Association, a nonprofit research and planning agency for the metropolitan region, urged Mayor Beame to continue building the Second Avenue line, and the group described his decision to postpone the line's construction as a "serious error" that would waste millions of dollars.[65] In June 1975, a public hearing was held concerning the MTA's plan to transfer funds from the Second Avenue Subway to the Archer Avenue Line project.[66] In September 1975, Beame issued a stop-work order for the line.[67] Construction of the line was halted on the section between Second and Ninth Streets, and no other funding was to be allocated to the line's construction.[67] Besides the Chrystie Street Connection, only three sections of tunnel had been completed; these tunnels were sealed.[9] The city did not anticipate that construction would resume until at least 1986.[53]: 112

By summer 1977, after construction had been halted for several months, residents of East Harlem reported that construction materials for the Second Avenue Subway were being stored on the streets, and open pits in the sidewalk had yet to be covered up. One engineer said that “we should be able to have things back to normal by spring 1978" if no problems were encountered.[68] Several East Harlem residents filed lawsuits against the city after receiving injuries from broken construction materials or missing sidewalks, while retailers reported that the open pits encouraged thieves to break into their stores, sometimes by going through the open pits.[69]

In 1978, when the New York City Subway was at its lowest point in its existence, State Comptroller Arthur Levitt stated that there were no plans to finish the line.[9] During the 1980s, plans for the Second Avenue line stagnated. Construction on the 63rd Street Lines continued; the IND portion of the line opened in 1989 and extended to 21st Street–Queensbridge in Long Island City, Queens, but it did not include a connection to the Second Avenue line.[70] In 1996, New York Magazine jokingly suggested that if New York City were to host an Olympic Games, there might finally be funding to finish the Second Avenue Subway.[71] Of this failure to complete construction, Gene Russianoff, an advocate for subway riders since 1981, stated: "It's the most famous thing that's never been built in New York City, so everyone is skeptical and rightly so. It's much-promised and never delivered."[70] By this time, the project was known as "the line that time forgot".[72]

Segments completed[]

When construction on the line was halted in 1975, three tunnel segments were completed: one from 99th to 105th Streets (1,815 feet (553 m)-long) and a second from 110th to 120th Streets (2,556 feet (779 m)-long), both under Second Avenue in East Harlem, and a third from Division to Canal Streets in Chinatown (738 feet (225 m)-long), under the Confucius Plaza apartment complex next to the Bowery.[9][73]: 9D-24 [72] They were not initially outfitted with track or signals.[74] In August 1982, the MTA put out advertisements in national journals announcing that the two tunnel segments in East Harlem were being put up for rent for temporary use, and that the rents on the tunnels were to last seven years. After UMTA approved the MTA's plan, the MTA dispersed advertisements.[75] The tunnels had no plumbing, ventilation, or access to the street, except through manhole covers on Second Avenue. To provide access to the tunnels, the MTA wanted to rent street-level rights that it had for subway entrances.[75] The sole respondent to these advertisements wanted to use the abandoned tunnels as a filing cabinet.[76] Over the next few decades, the MTA inspected and maintained the tunnel segments every two to three months,[77] spending $20,000 a year by the early 1990s to maintain the structural integrity of the streets above, as well as to keep the segments clean in case construction ever resumed. Trespassers would often camp in the tunnels until the MTA increased security.[78]

The tunnel section from 110th to 120th Streets was built with space for three tracks.[79] As part of the 1970s construction plan, under which this segment was constructed, there was no station planned at 116th Street.[36] The middle track in that area was to be used for inspecting trains.[80] As part of Phase 2, the section occupied by the middle track for the 116th Street station's island platform.[77]

The modern construction plan for the Second Avenue Subway, developed in 2004, would make use of most of these tunnel segments.[82] Phase 1 of service built new tunnels up to 99th Street, where the new tunnels connect to the tunnel segment between 99th and 105th Streets. The new tunnels between 96th and 99th Street are used for train storage of up to four trainsets, or two per track.[83][84] Phase 2 is planned to extend Q train service from 96th Street to 125th Street.[85][86] During Phase 2, both East Harlem segments will be connected, modified, and used for normal train service. In 2007, the MTA reported that the segments were in pristine condition.[74] In December 2016, there were rumors that the 110th–120th Streets segment might go unused, though the MTA refuted the claim.[87]

The fourth phase of construction will bring the Second Avenue line through Chinatown at an undetermined date. However, the tunnel under the Confucius Apartments is not planned to be used;[27][88]: 13 [89]: 51 [90] while original plans involved the Second Avenue line running at the same depth of the Sixth Avenue Line at the Grand Street station, that option would require the use of cut-and-cover construction methods, which would disrupt the community and require the demolition of several nearby structures.[88]: 9 [91]: 51 Instead the MTA has proposed a deeper tunnel alignment in this area, including a new lower level at Grand Street, to reduce construction impacts on the Chinatown community.[27][89][92] As a result, trains will be unable to use this tunnel segment; however, the MTA suggests that the tunnel segment could be used to store ancillary facilities for the subway line, such as a power substation or a ventilation facility.[27]

A contract for construction between 2nd and 9th Streets was also awarded in mid-1974. However, it is unclear how much work, if any, was performed on that section.[57][59]

1995–2017: Planning for current project[]

Second Avenue Subway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

With the city's economic and budgetary recovery in the 1990s, there was a revival of efforts to complete construction of the Second Avenue Subway. Rising ridership on the IRT Lexington Avenue Line, the only subway trunk line east of Central Park, demonstrated the need for the Second Avenue Line, as capacity and safety concerns rose.[93] The four-track IRT Lexington Avenue Line, the lone rapid transit option in the Upper East Side and East Harlem since the 1955 closure of the Third Avenue elevated, is the most crowded subway line in the country.[93] The line saw an average of 1.3 million daily riders in 2015.[93][94] This is more than the daily ridership of the entire Washington Metro system, which has the second-highest ridership in the U.S., as well as greater than the combined riderships of the rail transit systems of San Francisco and Boston.[93] Local bus routes are just as crowded during various times of the day, with the M15 local and Select Bus Service routes, which run on Second Avenue, seeing a combined annual ridership of 14.5 million or a daily ridership of about 46,029.[95][96]

The construction of the Second Avenue line would add two tracks to fill the gap that has existed since the elevated Second and Third Avenue Lines were demolished in the 1950s.[93] It would also be the largest expansion of the New York City Subway since the 1960s.[97] According to the line's final environmental impact statement, the catchment area of the line's first phase would include 200,000 daily riders.[94][98][99][100]

Planning begins[]

In 1991, then-New York Governor Mario Cuomo allocated $22 million to renew planning and design efforts for the Second Avenue line. Construction would not begin until at least 1997.[101] However, the MTA removed these funds from its capital budget two years later, as it was facing budget cuts.[102] In 1995, the MTA began its Manhattan East Side Alternatives (MESA) study, both a Major Investment Study (MIS) and a Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS), seeking ways to alleviate overcrowding on the Lexington Avenue Line and improve mobility on Manhattan's East Side. The study analyzed several alternatives, such as improvements to the Lexington Avenue Line to increase capacity, enhanced bus service with dedicated lanes, and light rail or ferry service on the East Side.[10][103]: 7–8

The favored alternative, build alternative 1, included a subway running down Second Avenue from 125th Street in Harlem to the existing Lexington Avenue–63rd Street station with provisions for expansion to the Bronx and to Lower Manhattan.[10] Second Avenue was chosen over Third Avenue, because Third Avenue was too close to the Lexington Avenue Line, as well as having significant property impacts, increased construction complexity and cost, and increased travel times resulting from slower operating speeds.[103]: 17 Second Avenue was chosen over First Avenue, because it would be too difficult to construct near the Queensboro Bridge, the United Nations and the Queens-Midtown Tunnel.[10]

The MTA started the Lower Manhattan Access Study (LMA) in November 1997 in order to determine the best new transport connections to the New York City suburbs. The construction of the Second Avenue Subway from 63rd Street to Lower Manhattan was one of the five build alternatives developed by the study.[103]: 6, 7

1999 Draft Environmental Impact Statement[]

The 1999 Draft Environmental Impact Statement only proposed new subway service from 63rd Street north up Second Avenue to 125th Street via the Broadway Line to Lower Manhattan. All trains would have been routed down the Broadway Line express tracks, which are the only tracks on the Broadway Line which connect to the 63rd Street Line. In order to provide access to Lower Manhattan, and to allow for congestion reduction on the Lexington Avenue Line, the "Canal Street Flip" was proposed. As built, the tracks at Canal Street are set up so that the local tracks continue into the Financial District and then enter Brooklyn through the Montague Street Tunnel, while the express tracks continue to Brooklyn directly, crossing the Manhattan Bridge.[104]: 20–21 The "Canal Street Flip" would have flipped the local and express tracks at Canal Street, having local trains run via the Manhattan Bridge, and in turn having the express trains continue south on the Broadway Line through Lower Manhattan and through the Montague Street Tunnel into Brooklyn. To construct the "Flip" 3,450 feet (1,050 m) of track would have been reconstructed, the two side platforms would have been widened, columns would have been relocated, and two new switches would have been installed.[18]: 15·26 to 15·27 Once the construction of full-length Second Avenue Subway was approved, this option was discarded.[104]: 21

The service plan with the "Canal Street Flip," according to the December 1998 "Manhattan East Side Transit Alternative Study," would have had R trains run via the Second Avenue line, which was only planned to run from 63rd Street to 125th Street. R trains would become the Broadway express under this plan, using the BMT 63rd Street Line to access the Second Avenue line and continuing to 125th Street.[105] The service would have operated 25 trains per hour (tph) between 125th Street and City Hall, 20 tph between City Hall and Whitehall Street, and 10 tph between Whitehall Street and Bay Ridge–95th Street via the Montague Street Tunnel. A reconstruction of a junction near Canal Street, called the "Canal Flip," would have provided a direct connection between the express tracks of the Broadway Line and Lower Manhattan, allowing the route to operate.[105] To allow R trains to short-turn at City Hall, the station's unused lower level would have been reactivated, requiring upgrades for the platforms and tracks, including their lengthening, in addition to the installation of tail tracks. During construction, the station's upper level would have had to been underpinned.[18]: 15–27 To replace the R on Queens Boulevard, a Broadway Local T route (distinct from the currently proposed Second Avenue Local T route) would have been created, running between Continental Avenue and Bay Parkway via Broadway local and the Manhattan Bridge. The "Canal Street Flip" would have provided a direct connection between the local tracks and the Manhattan Bridge. The N, which ran local on Broadway, would have been rerouted from the Montague Street Tunnel to the Manhattan Bridge.[105]: 76–80

Initially, a spur to Grand Central Terminal was considered, which would have run via 44th Street as a way to divert riders from the 4 and 5 routes, which run express on the Lexington Avenue Line. Service on this spur could not be as frequent as that on Lexington Avenue as there would not be enough capacity on Second Avenue, and as a result this plan was dropped.[103]: 17

South of 14th Street, there were two possible options to decide between. Option A would continue the subway beneath Chrystie Street, St. James Place and Water Street to a terminal in Lower Manhattan. Option B would connect the new subway to the existing Nassau Street Loop tracks J1 and J2 at Kenmare Street to provide access to Lower Manhattan.[104]: 21–22 [106] This option has been proposed as part of plans for the Second Avenue Subway from the 1940s and 1950s. Cross-platform transfers would be available at Canal Street and Chambers Street to the Nassau Street Line routes. It would allow Second Avenue trains to have access to Brooklyn using the underutilized Montague Street Tunnel.[104]: 25–26 [106] This option would have a lower cost than the Water Street option as less tunnel would need to be constructed. The Nassau option would attract more riders to the subway system because of additional service to Brooklyn, but the Water Street option would provide greater coverage in Manhattan and would be better at relieving congestion on the Lexington Avenue Line.[104]: 26–27 Because the platforms on the BMT Eastern Division are shorter than those on the rest of the B Division, those on the Nassau Street Line south of Chambers Street would have to be lengthened by about 120 feet (37 m), to a total of 615 feet (187 m).[104]: 26 The tracks would have to be reconfigured, the passenger circulation capacity would have to be increased, and the service plan south of Chambers Street would have to be modified, to provide sufficient capacity to accommodate the additional trains that Second Avenue Subway service would require. The Nassau Street Line connection would have run through a new tunnel that first turns to the east to align under Forsyth Street before turning west and joining the Nassau Street Line along Kenmare Street.[104]: 25–26 [103]: 17

The Water Street option was chosen even though it would cost $360 million more because of the additional benefits it would provide. The Nassau Street option would have required the reorganization of the existing services on the Nassau Street Line, and passengers entering via the Williamsburg Bridge would not have direct service to destinations in other parts of Brooklyn.[104]: 26–27 Additionally, over a period between two and three years long, service on the Nassau Street Line would have been required to be shut down during late nights and/or weekend hours. The Nassau Street option would not have the capacity for future Queens service via the 63rd Street Tunnel.[104]: 26

Originally, the 125th Street station was to have been constructed parallel to the Lexington Avenue Line, curving below private property to join Second Avenue at 115th Street. This option was favored as it would have allowed an eventual extension of the Second Avenue Subway to the Bronx via the IRT Pelham Line, while still providing a transfer at 125th Street to the Lexington Avenue Line.[104]: 18 [103]: 15 Under this option, 116th Street would not have a station, but because of requests by the local community, the SDEIS evaluated the inclusion of this station. The s-curve options were not feasible because of the large curve radius required for efficient and fast subway operation.[104]: 18 [103]: 15 As a result, the alignment at 125th Street was changed. Instead, the line would continue via Second Avenue until 125th Street, when it would then curve under a small number of private properties before heading west on 125th Street. A future extension to the Bronx would be allowed from Second Avenue as opposed to Lexington Avenue. This alignment also allows for the construction of a storage yard north of 125th Street.[104]: 18

Build alternative two would involve the addition of a separate light rail service between Union Square and Broad Street that would serve the Lower East Side and Lower Manhattan.[15][103]: 7–8 Other alternatives including building in-fill stations on various lines (including the 63rd Street Line at First Avenue, at First Avenue on the Broadway Line, at First Avenue on the Flushing Line, and Avenue C on the Canarsie Line), building an elevated train line along Second or First Avenues, lengthening the platforms on the Lexington Avenue Line to accommodate twelve-car trains, or connecting the northern part of the Lexington Avenue Line (either the local or express tracks), which would be converted to B Division service, to the Broadway Line.[10][103]: 7–8 Due in part to strong public support, the MTA Board committed in April 2000 to building a full-length subway line along the East Side, from East Harlem to Lower Manhattan.[107][103]: 18 In May 2000, the MTA Capital Program Review Board approved the MTA's 2000–2004 Capital Program, which allocated $1.05 billion for the construction of the Second Avenue Subway.[108][103]: 18 The next year, a contract for subway design was awarded to DMJM Harris/Arup Joint Venture.[9] On December 19, 2001, the Federal Transit Administration approved the start of preliminary engineering on a full-length Second Avenue Subway.[10]

Approval and preparation for construction[]

When Hillary Clinton was running for New York State Senator in 2000, she stated that she supported the construction of multiple major infrastructure projects in New York, such as the Second Avenue Subway, East Side Access, and rail links to LaGuardia and JFK Airports.[109] In 2003, two million dollars in preliminary funding for the subway were provided by Congressmen Maurice Hinchey and John Sweeney.[110] The MTA's final environmental impact statement (FEIS) was approved in April 2004; this latest proposal is for a two-track line from 125th Street and Lexington Avenue in Harlem, down Second Avenue to Hanover Square in the Financial District.[81]

The new subway line will actually carry two regular services. The full-length Second Avenue line, extending from Harlem to the Financial District, is to be given the color turquoise and the letter designation T.[111] However, a rerouted Q, the line's other service, will begin carrying passengers first (supplemented by some rush-hour N trains).[112] The MTA plan calls for building the Second Avenue Subway in four segments with connections to other subway lines. The first segment, Phase 1, rerouted the Q along the Broadway Express, via the BMT 63rd Street Line, and north along Second Avenue to the Upper East Side at 96th Street. Phase 2 will extend the rerouted Q train, along with the rush-hour N trips, to 125th Street and Lexington Avenue. In Phase Three, the new T train will run from 125th Street to Houston Street. The final phase will extend T train service from Houston Street to Hanover Square in Lower Manhattan.[10][113]

In order to store the 330 additional subway cars needed for the operation of the line, the 36th–38th Street Yard would be reconfigured. In addition, to allow for train storage, alongside the main alignment, there would be storage tracks between 21st Street and 9th Street. The Second Avenue Subway is chained as "S".[10] The track map in the 2004 FEIS showed that all stations, except for Harlem–125th Street, would have two tracks and one island platform.[114][115] 72nd Street and Harlem–125th Street were conceived as three-track, two-platform stations, but plans for both were scaled back. At 72nd Street, this would have allowed trains from the Broadway Line to reverse without interfering with service on Second Avenue, as well as provided additional operational flexibility that could be used for construction work and non-revenue moves.[104]: 20 However, to reduce costs, the 72nd Street station was ultimately constructed with two tracks and one platform.[116][117] In July 2018, the 125th Street station was also scaled down to a two-track, one-platform station because the MTA had ascertained that two-tracked terminals would be sufficient to handle train capacities, and that building a third track would have caused unnecessary impacts to surrounding buildings.[118]: 13

In August 2006, the MTA revealed that all future subway stations—including stations on the Second Avenue Subway and the 7 Subway Extension, as well as the new South Ferry station—would be outfitted with air-cooling systems to reduce the temperature along platforms by as much as 10 °F (6 °C).[119] In early plans, the Second Avenue Subway was also to have platform screen doors to assist with air-cooling, energy savings, ventilation, and track safety,[120] but this plan was scrapped in 2012 due to costs and operational challenges.[121]

The 2-mile (3.2 km)[122] first phase will be within budget, at $4.45 billion.[122][123] Its construction site was designated as being from 105th Street and Second Avenue to 63rd Street and Third Avenue.[124] Deep bore tunneling methods were to be used in order to avoid the disruptions for road traffic, pedestrians, utilities and local businesses produced by cut-and-cover methods of past generations. Stations were to retain cut-and-cover construction.[2][125] The total cost of the 8.5-mile (13.7 km) line is expected to exceed $17 billion.[72] In 2014, MTA Capital Construction President Dr. Michael Horodniceanu stated that the whole line may be completed as early as 2029,[126] and would serve 560,000 daily passengers upon completion;[127] however, as of December 2016, only Phases 1 and 2 would be completed by 2029.[128] The line is described as the New York City Subway's "first major expansion" in more than a half-century.[129] However, its completion is in doubt, with one construction manager saying that the first phase of the project is "four and a half billion dollars for three stations," and that there are fifteen stations that need to be built for the entire line.[123]

2007–2017: First phase[]

Beginning of construction[]

Second Avenue Subway plans for Phase 1 were only allowed to proceed because New York voters passed a transportation bond issue on November 8, 2005, allowing for dedicated funding allocated for that phase. Its passage had been seen as critical to its construction, but the bond was passed only by a narrow margin, with 55 percent of voters approving and 45 percent disapproving. After warning that failure to pass the act would doom the project, MTA chairman Peter S. Kalikow stated, "Now it's up to us to complete the job."[130] On December 18, 2006, the U.S. Department of Transportation announced that they would allow the MTA to commit up to $693 million in funds to begin construction of the Second Avenue Subway and that the federal share of such costs would be reimbursed with FTA transit funds, subject to appropriations and final labor certification.[131]

Preliminary engineering and a final tunnel design was completed by a joint venture between AECOM and Arup.[132][133] The first phase was originally supposed to include a core tunneling section between 62nd and 92nd Streets, as well as a spur from Third Avenue/63rd Street to Second Avenue/65th Street. The 96th Street station cavern, as well as existing tunnels, would allow the first phase's trackage to run from 62nd to 105th Streets.[134][135] Before construction started, the MTA revised their plans so that the construction of the section between 62nd and 65th Streets was postponed.[136] On March 20, 2007, upon completion of preliminary engineering, the MTA awarded a contract for constructing the tunnels between 92nd and 63rd Streets, a launch box for the tunnel boring machine (TBM) at 92nd to 95th Streets, and access shafts at 69th and 72nd Streets. This contract, valued at $337 million, was awarded to S3, a joint venture of Schiavone Construction, Skanska USA Civil, and J.F. Shea Construction.[137][138][139][140][141] A ceremonial groundbreaking took place on April 12, 2007,[2] in a tunnel segment built in the 1970s at 99th Street.[142] At the time, it was announced that passengers would be able to ride trains on the new line by the end of 2013.[143] Actual construction work began on April 23, 2007, with the relocation of utility pipes, wires, and other infrastructure. This process took 14 months, nearly double the MTA's anticipated eight months.[144]

In November 2007, Mary Peters, the United States Secretary of Transportation, announced that the Second Avenue Subway would receive $1.3 billion in federal funding for the project's first phase, to be funded over a seven-year period.[145] However, due to cost increases for construction materials and diesel fuel affecting the prices of contracts not yet signed, the MTA announced in June 2008 that certain features of the Second Avenue Subway would be simplified to save money. One set of changes, which significantly reduces the footprint of the subway in the vicinity of 72nd Street, is the alteration of the 72nd Street Station from a three-track, two-platform design to a two-track, single island platform design, paired with a simplification of the connection to the Broadway Line spur.[116] Supplemental environmental impact studies covering the changes for the proposed 72nd Street and 86th Street stations were completed in June 2009.[146][147]

On May 28, 2009, the MTA awarded a $325 million contract to E.E. Cruz and Tully Construction Co., a joint venture and limited liability company, to construct the 96th Street station box. Work on this contract began in July.[148] In June 2009, the first of three contracts for the 86th Street station was awarded for the advance utility relocation work and construction of cut-and-cover shaft areas at 83rd and 86th Streets.[149] Muck houses were built to store all the dirt and debris from the project.[2]

During construction, two buildings had to be evacuated in June 2009. On June 5, an apartment building at 1772 Second Avenue was evacuated by the NYC Department of Buildings (DOB) after it was determined that the building was in danger of collapse.[150] Then on June 29, the DOB evacuated a mixed use building at 1768 Second Avenue/301 East 92nd Street because it too was in danger of collapse.[151] The evacuation of these two buildings delayed the contractor's plan to use controlled blasting to remove bedrock in the southern section of the launch box.[152] Until the blasting permits could be issued, MTA required contractors to use mechanical equipment to remove the bedrock, which is slower than blasting out the rock.[153]

The tunnel boring machine was originally expected to arrive six to eight months after construction began, but the utility relocation and excavation required to create its "launch box" delayed its deployment until May 2010.[132] On May 14, 2010, MTA's contractors completed the TBM installation and turned it on at the Second Avenue Subway launch box at 96th Street and boring southward to connecting shafts built at 86th and 72nd Streets.[154][155][156] On October 1, 2010, MTA awarded a $431 million contract to joint venture SSK Constructors for the mining of the tunnels connecting the 72nd Street station to the existing Lexington Avenue–63rd Street station, and for the excavation and heavy civil structures of the 72nd Street station.[157]: 301 A subsequent contract was awarded to Skanska Traylor Joint Venture for excavation of the cavern at the 86th Street station on August 4, 2011.[158] In January 2011, MTA awarded Judlau Contracting a 40-month, $176.4 million contract to rebuild and enlarge the Lexington Avenue–63rd Street station.[159][160]

Significant progress[]

Meanwhile, the tunnel boring machine dug at a rate of approximately 50 feet (15 m) per day. The machine finished its run at the planned endpoint under 65th Street on February 5, 2011.[162] S3 partially disassembled the TBM and backed it out of the tunnel. It was repositioned in the east starter tunnel to begin boring again.[163] Because the east side of Second Avenue has some soft ground not compatible with the Robbins TBM, ground-freezing was undertaken to prepare the soil for the TBM.[154][164][165]

On March 28, 2011, S3, having completed its task of completing the 7,200-foot (2,200 m) west tunnel to 65th Street, began drilling the east tunnel, with the first 200 feet (61 m) being through soil frozen by S3 using calcium chloride solution fed through a network of pipes. The TBM drilling the east tunnel then negotiated the curve onto 63rd Street and broke through the bellmouth at the existing Lexington Avenue–63rd Street station.[166][167] That bellmouth had been built in the late 1970s and early 1980s as part of the construction of the 63rd Street Line in anticipation of the construction of the Second Avenue line.[168]: 31 [105]: D-5 The portion of the west tunnel remaining to be created was then mined using conventional drill-and-blast methods, because the curve S3 construction teams would have to negotiate was too tight for the TBM.[166] On September 22, 2011, the TBM completed its run to the Lexington Avenue–63rd Street station's bellmouth.[161][169] This major milestone was celebrated with a big ribbon-cutting to mark the TBM breaking through to the existing bellmouth.[170] The TBM had dug a total of 7,789 feet (2,374 m) for the east tunnel.[167]

The MTA opened a Second Avenue Subway Community Information Center for Phase 1 on July 25, 2013.[171][172][173] It was located at 1628 Second Avenue between 84th and 85th Streets, near the line's 86th Street station.[174] In the three years that followed, the center was visited over 20,000 times.[175]

The final contract, for architectural and mechanical and electrical work at 72nd, 86th, and 96th Street stations; rehabilitation of the Lexington Avenue–63rd Street station; and the Systems Contract (track, signals, and communications) for the entire Phase 1 area was awarded on June 1, 2013.[176] On a July 2013 "report card" that indicated the progress of the subway by Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney, the construction progress got a "B".[177]

Blasting for the station caverns was finished in November 2013, and the muck houses were taken down at around the same time.[178] In the winter of 2013, many of the tracks and signal panels began to arrive at the construction site, to be installed on the line over the next few years.[179] It was reported in November 2013 that one third of the tracks for the line had arrived, for the segments of track between 87th and 105th Streets;[179] the tracks were being stored at 96th Street station.[180] On May 2, 2014, it was reported that Phase 1 of the line was 66% complete, and six of the ten construction contracts awarded were already being worked on. As of May 21, 2015, the first phase of construction was more than 80% complete.[181] By August 2015, the construction project was 84.3% complete, with all ten Phase 1 construction contracts having been awarded and 5 of them having been completed.[182]

Push for completion[]

On February 24, 2016, the MTA allocated $66 million to speed up the construction of the first phase so that it could open in December.[183] However, in June of that year, it was reported that contractors for the MTA were not expending extra resources to accelerate the last portion of Phase 1 construction,[184] and that the MTA had only completed 67% of testing, with the line requiring another 1,100 equipment tests by October 2016 in order to be deemed operational.[185] The contractors and the MTA blamed the delays on each other, with the MTA saying that the contractors did not show up to work on certain days; the contractors, on the other hand, said that the MTA had asked for over 2,500 design changes during construction, and in some cases, the contractors had to destroy and rebuild sidewalks, rooms, entrances, and other design elements that had already been built.[186]

In a public meeting in May 2016, the MTA unveiled the first iteration of the New York City Subway map that included the Second Avenue Subway and a rerouted Q service.[187] At the meeting, the MTA also made several suggestions for service changes, including making the N train express in Manhattan and replacing the Queens section of the Q, as well as the Manhattan local section of the N, with a reinstated W train.[188]

On May 16, 2016, Congresswoman Maloney released another report card on the project. The overall grade improved from a "B" to an "A-",[189] with the caveat that the December 2016 deadline be met.[190] By July 2016, the first phase was 96.3% complete, with only systems testing, architectural finishes, streetscape restorations, and some equipment installations to be completed.[191] However, news outlets reported that the Second Avenue Subway had a "significant risk" of a delayed opening.[192][193][194] The test train for the subway line was not set to run until October 2016, despite the line being projected to open within two months of that date.[192] Also, contractors had only reached 70% of the construction milestones for June 2016, and 80% of the May 2016 milestones. For instance, communications systems at the stations were not finished, despite the fact that these systems should have been wired already, and the elevator at 72nd Street had not been delivered yet. As of July 25, 2016, construction spending was only $32 million for the month, even though a monthly spending goal of $46 million was needed to complete the project on time.[194]

The third rail was energized and test trains began operating in September 2016. Non-revenue Q trains ran through the subway in November 2016.[195] Test trains began running through the new line on October 9, 2016 with weights to simulate rush hour loads, even though equipment installations at two stations, as well as a battery of tests, still needed to be completed in order for the line to be opened to passenger service.[196][197][198] Shortly before the first test trains ran, the system's track geometry car determined that the twin bores of the 63rd Street Connector were too narrow for trains consisting of 75-foot (23 m) cars (i.e. trains made of R46s, R68s, or R68As) to enter the line. To accommodate trains of these longer cars, crews shaved down parts of the tunnel walls by mid-October 2016, in time for the test trains.[199] Also in October, new subway signs and maps were erected systemwide in relation to Second Avenue Subway-related service changes.[200] More than 1,300 signs were installed in over forty stations.[201]

By late October, the testing for elevators and fire alarms at 72nd Street still had not been completed, and the MTA said that there was a possibility that the subway could open with trains temporarily bypassing 72nd Street. This had been done before in September 2016, when subway trains in Chelsea temporarily bypassed several stations along 23rd Street due to bombings.[200][202] There was a concern that 86th Street was also not completed, with three escalators not installed yet. The two stations were only conducting fourteen equipment tests a week, but there needed to be forty tests per week in order to ensure that the line would open on time.[202] The tentative opening date was also clarified to "by December 31," with a possibility of a delayed opening.[129][200][203] However, an engineer affiliated with the MTA stated that there was a possibility that the line could be delayed to 2017.[204]