Honnō-ji Incident

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2007) |

| Honnō-ji Incident | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Sengoku period | |||||||

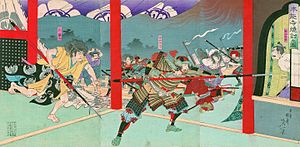

Incident at Honnō-ji, Meiji-era print | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Oda forces under Akechi Mitsuhide's command | Inhabitants and garrison of Honnō-ji, courtiers, merchants, artists, and servants of Oda Nobunaga | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 13,000 | Nobunaga, Nobutada, Mori Ranmaru, a handful of other Oda retainers,[1] and the small garrison of Kyoto 70 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown, presumably minimal | Oda Nobunaga, Mori Ranmaru, Oda Nobutada, and many others | ||||||

The Honnō-ji Incident (本能寺の変, Honnō-ji no Hen) was the death place of Oda Nobunaga, where he committed Seppuku at the Honnō-ji temple in Kyoto on 21 June 1582. Nobunaga was betrayed by his general Akechi Mitsuhide during his campaign to consolidate centralized power in Japan under his authority.[2] Mitsuhide ambushed the unprotected Nobunaga at Honnō-ji and his eldest son Oda Nobutada at Nijō Palace, which resulted in both committing seppuku. Nobunaga was avenged by his retainer Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who defeated Mitsuhide in the Battle of Yamazaki, paving the way for Hideyoshi's supremacy over Japan.

Mitsuhide's motive for assassinating Nobunaga is unknown and there are multiple theories for his betrayal.

Context[]

By 1582, Oda Nobunaga was at the height of his power as the most powerful daimyō in Japan during his campaign of unification under his authority. Nobunaga had destroyed the Takeda clan earlier that year at the Battle of Tenmokuzan and had central Japan firmly under his control, with his only rivals, the Mōri clan, the Uesugi clan, and the Hōjō clan, each weakened by internal affairs. After the death of Mōri Motonari, his grandson Terumoto strove only to maintain the status quo, aided by his two uncles, as per Motonari's will. Hōjō Ujiyasu, a renowned strategist and domestic manager, had also died, leaving his less prominent son Ujimasa in place. Finally, the death of Uesugi Kenshin left the Uesugi clan, devastated also by an internal conflict between his two adopted sons, weaker than before.

It was at this point that Nobunaga began sending his generals aggressively in all directions to continue his military expansion. Nobunaga ordered Hashiba Hideyoshi to attack the Mōri clan; Niwa Nagahide to prepare for an invasion of Shikoku; Takigawa Kazumasu to watch the Hōjō clan from Kōzuke Province and Shinano Province; and Shibata Katsuie to invade Echigo Province, the home domain of the Uesugi clan. At the same time, Nobunaga also invited his ally Tokugawa Ieyasu to tour the Kansai region in celebration of the demise of the Takeda clan. Around this time, Nobunaga received a request for reinforcements from Hashiba Hideyoshi, whose forces were stuck besieging the Mōri-controlled Takamatsu Castle. Nobunaga then parted ways with Ieyasu, who went on to tour the rest of Kansai while Nobunaga himself made preparations to aid Hashiba in the frontline. Nobunaga ordered Akechi Mitsuhide also to go to Hideyoshi's aid and travelled to Honnō-ji temple in Kyoto, his usual resting place when he stopped by in the capital. Nobunaga was unprotected at Honnō-ji, deep within his territory, with the only people he had around him being court officials, merchants, upper-class artists, and dozens of servants.

Akechi's treachery[]

Upon receiving the order, Mitsuhide returned to Sakamoto Castle and moved to his base in Tanba Province. Around this time, Mitsuhide had a session of renga with several prominent poets, where he made clear his intentions of rising against Nobunaga. Mitsuhide saw an opportunity to act, when not only was Nobunaga resting in Honnō-ji and unprepared for an attack, but all the other major daimyō and the bulk of Nobunaga's army were occupied in other parts of the country.

Mitsuhide led his army toward Kyoto under the pretense of following the order of Nobunaga. It was not the first time that Nobunaga had demonstrated his modernized and well-equipped troops in Kyoto, so the march toward Kyoto did not raise any suspicion from Mitsuhide's men. As they were crossing the Katsura River, Mitsuhide announced to his troops that "The enemy awaits at Honnō-ji!" (敵は本能寺にあり, Teki wa Honnō-ji ni ari). Before dawn, the Akechi army had the Honnō-ji temple surrounded in a coup d'état. Nobunaga and his servants and bodyguards resisted, but they realized it was futile against the overwhelming numbers of Akechi troops. Nobunaga then, with the help of his young page, Mori Ranmaru, committed seppuku. Reportedly, Nobunaga's last words were "Ran, don't let them come in ..." to Ranmaru, who then set the temple on fire as Nobunaga requested so that no one would be able to get his head. Ranmaru then followed suit, committing seppuku himself. His loyalty and devotion makes him a revered figure in Japanese history. Nobunaga's remains were never found, a fact often speculated about by writers and historians.

After capturing Honnō-ji, Mitsuhide attacked Nobunaga's eldest son and heir, Oda Nobutada, who was staying at the nearby Nijō Palace. Nobutada also committed seppuku.[2]:69 Mitsuhide tried to persuade Oda vassals in the vicinity of Kyoto to recognize him as the new master of former Oda territories. Then, Mitsuhide entered Nobunaga's Azuchi Castle east of Kyoto and began sending messages to the Imperial Court to boost his position and force the court to recognize his authority as well.

Reasons for the coup[]

Akechi Mitsuhide's reasons for the coup are a mystery and have been a source of controversy and speculation. Although there have been several theories, the reason the historian Kuwata Tadachika put forth was that Mitsuhide bore a personal grudge.[3]:242 Other theories maintain that Mitsuhide acted out of fear, had the ambition to take over Japan, was simply acting to protect the Imperial Court (whose authority Nobunaga did not respect), or was trying to remove the iconoclastic revolutionary. Another theory is that Mitsuhide did not enjoy the cruelty of Nobunaga. Many think it was a combination of at least some of the above suggested reasons.

When Nobunaga invited Tokugawa Ieyasu to Azuchi Castle, Akechi was the official in charge of catering to the needs of Ieyasu's group. He was later removed from this post for unknown reasons. One story spoke of Nobunaga yelling at him in front of the guests for serving rotten fish.

Another story claims that when Nobunaga gave Akechi the order to assist Hashiba Hideyoshi, it was somehow hinted that Akechi would lose his current territories and would have to fight for land which was not even under Oda control yet. As Nobunaga had sent two senior retainers under him, Sakuma Nobumori and Hayashi Hidesada, into exile for poor performance, Akechi might have thought that he could suffer a similar fate. Akechi was already in his early fifties, and some believe he might have felt insecure about such a grim future.

Furthermore, when invading Tanba Province, Akechi Mitsuhide supposedly sent his mother as hostage to Hatano Hideharu, the castellan of Yakami Castle, to convince him to surrender. Nobunaga, however, had Hatano Hideharu executed, and this action caused former Hatano retainers to kill Akechi’s mother.[2]:230 Akechi Mitsuhide felt humiliated and depressed by this and eventually decided to kill his master. This story, however, began to circulate only during the Edo period, and is of dubious historical origin.

Luís Fróis wrote that Mitsuhide liked to use treachery and diversion as his strategy. He also suggested daimyōs disliked Mitsuhide because he did not belong to the fudai clan, which had served his master's clan for a long time. Many books said Nobunaga insulted and kicked, or even forced Mitsuhide to drink sake at a party, even though he was not a heavy drinker.

Before Akechi began his march toward Chugoku, he held a renga session at the shrine on Mount Atago. The beginning line, Toki wa ima, ame ga shita shiru satsuki kana (時は今 雨がした滴る皐月かな), translates to "The time is now, the fifth month when the rain falls." However, there are several homonyms in the line, such that it could be taken as a double entendre. An alternate meaning, without changing any of the pronunciations, would be: 時は今 天が下治る 皐月かな. Thus it has also been translated as "Now is the time to rule the world: It's the fifth month!" In this case, the word toki, which means "time" in the first version, sounds identical to Akechi's ancestral family name, "Toki" (土岐).[3]

It is also believed Akechi may have been manipulated by Ieyasu or Hideyoshi, since the coup presented clear prospects of profit for both of them[4] (Hideyoshi ruled the country, and Ieyasu became the number two, avenging his wife and child).

Oda Nobutaka, third son of Nobunaga, wrote a poem before his death cursing Toyotomi Hideyoshi under his court title of Hashiba Chikuzen(-no-kami), which he used before becoming Kampaku.

After the Honnō-ji Incident[]

Quickly making peace with the Mōri clan, Hideyoshi headed to Kyoto, joined by Niwa Nagahide and Oda Nobutaka in Osaka. Marching toward Kyoto, he defeated Mitsuhide at the Battle of Yamazaki. Mitsuhide was killed by bandits as he tried to flee.[5]

With the help of his retainer and ninja leader Hattori Hanzō, Ieyasu first toured Sakai, then fled through several provinces and crossed the mountains of Iga Province, finally reaching the shore in Ise Province. He returned to his home Mikawa Province by sea, and it took him so long that by the time he consolidated his position, Hideyoshi had already had most of Nobunaga's territories under firm control.

Takigawa Kazumasu suddenly faced the assault of the Hōjō clan and lost most of his land there, a defeat that cost him his previous prestige in the Oda clan.

Shibata Katsuie and his forces in the north were bogged down by an Uesugi counterattack in Echizen Province and remained unable to act for quite a while. He would later fall in the Battle of Shizugatake against Hideyoshi a year later.

The fact that no one else had the chance, resources, or ability to act decisively ensured Hashiba Hideyoshi's supremacy and spiritual inheritance of Oda Nobunaga's legacy.

See also[]

- Tainei-ji incident – a similar coup in 1551 where a powerful daimyō of western Japan is forced to commit suicide

- Honnōji Hotel is a 2017 comedy mystery drama that takes places around the Honnō-ji Incident

Notes[]

- ^ Naramoto, pp. 296–305

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Turnbull, Stephen (2000). The Samurai Sourcebook. London: Cassell & C0. p. 231. ISBN 1854095234.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sato, Hiroaki (1995). Legends of the Samurai. New York: Overlook Duckworth. p. 241,245. ISBN 9781590207307.

- ^ Turnbull, S.R. (1977). The Samurai. New York: MacMillan Publishing Co., Inc. p. 164. ISBN 9780026205405.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen (2010). Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 26-29. ISBN 9781846039607.

References[]

- Naramoto Tatsuya (1994). Nihon no Kassen. Tokyo: Shufu to Seikatsusha.

- De Lange, William. Samurai Battles: The Long Road to Unification. Toyp Press (2020) ISBN 978-949-2722-232

- 1582 in Japan

- Conflicts in 1582

- Battles of the Sengoku period

- Military coups in Japan

- 16th-century coups d'état and coup attempts

- History of Kyoto