Hydrogen line

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2008) |

The hydrogen line, 21-centimeter line, or H I line[1] is the electromagnetic radiation spectral line that is created by a change in the energy state of neutral hydrogen atoms. This electromagnetic radiation has a precise frequency of 1420405751.768(2) Hz,[2] which is equivalent to the vacuum wavelength of 21.106114054160(30) cm in free space. This wavelength falls within the microwave region of the electromagnetic spectrum, and it is observed frequently in radio astronomy because those radio waves can penetrate the large clouds of interstellar cosmic dust that are opaque to visible light. This line is also the theoretical basis of the hydrogen maser.

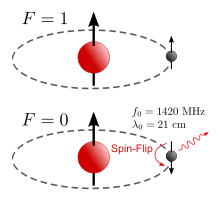

The microwaves of the hydrogen line come from the atomic transition of an electron between the two hyperfine levels of the hydrogen 1 s ground state that have an energy difference of 5.8743261841116(81) μeV [9.411708152678(13)×10−25 J]. It is called the spin-flip transition. The frequency, ν, of the quanta that are emitted by this transition between two different energy levels is given by the Planck–Einstein relation E = hν. According to that relation, the photon energy of a photon with a frequency of 1420405751.768(2) Hz is 5.8743261841116(81) μeV [9.411708152678(13)×10−25 J]. The constant of proportionality, h, is known as the Planck constant.

Cause[]

The ground state of neutral hydrogen consists of an electron bound to a proton. Both the electron and the proton have intrinsic magnetic dipole moments ascribed to their spin, whose interaction results in a slight increase in energy when the spins are parallel, and a decrease when antiparallel. The fact that only parallel and antiparallel states are allowed is a result of the quantum mechanical discretization of the total angular momentum of the system. When the spins are parallel, the magnetic dipole moments are antiparallel (because the electron and proton have opposite charge), thus one would expect this configuration to actually have lower energy just as two magnets will align so that the north pole of one is closest to the south pole of the other. This logic fails here because the wave functions of the electron and the proton overlap; that is, the electron is not spatially displaced from the proton, but encompasses it. The magnetic dipole moments are therefore best thought of as tiny current loops. As parallel currents attract, the parallel magnetic dipole moments (i.e., antiparallel spins) have lower energy.[3] The transition has an energy difference of 5.87433 μeV that when applied in the Planck equation gives:

where h is the Planck constant and c is the speed of light.

This transition is highly forbidden with an extremely small transition rate of 2.9×10−15 s−1,[4] and a mean lifetime of the excited state of around 10 million years. A spontaneous occurrence of the transition is unlikely to be seen in a laboratory on Earth, but it can be artificially induced using a hydrogen maser. It is commonly observed in astronomical settings such as hydrogen clouds in our galaxy and others. Owing to its long lifetime, the line has an extremely small natural width, so most broadening is due to Doppler shifts caused by bulk motion or nonzero temperature of the emitting regions.

Discovery[]

During the 1930s, it was noticed that there was a radio 'hiss' that varied on a daily cycle and appeared to be extraterrestrial in origin. After initial suggestions that this was due to the Sun, it was observed that the radio waves seemed to propagate from the centre of the Galaxy. These discoveries were published in 1940 and were noted by Jan Oort who knew that significant advances could be made in astronomy if there were emission lines in the radio part of the spectrum. He referred this to Hendrik van de Hulst who, in 1944, predicted that neutral hydrogen could produce radiation at a frequency of 1420.4058 MHz due to two closely spaced energy levels in the ground state of the hydrogen atom.

The 21 cm line (1420.4 MHz) was first detected in 1951 by and Purcell at Harvard University,[5] and published after their data was corroborated by Dutch astronomers Muller and Oort,[6] and by Christiansen and Hindman in Australia. After 1952 the first maps of the neutral hydrogen in the Galaxy were made, and revealed for the first time the spiral structure of the Milky Way.

Uses[]

In radio astronomy[]

The 21 cm spectral line appears within the radio spectrum (in the L band of the UHF band of the microwave window to be exact). Electromagnetic energy in this range can easily pass through the Earth's atmosphere and be observed from the Earth with little interference.

Assuming that the hydrogen atoms are uniformly distributed throughout the galaxy, each line of sight through the galaxy will reveal a hydrogen line. The only difference between each of these lines is the Doppler shift that each of these lines has. Hence, one can calculate the relative speed of each arm of our galaxy. The rotation curve of our galaxy has been calculated using the 21 cm hydrogen line. It is then possible to use the plot of the rotation curve and the velocity to determine the distance to a certain point within the galaxy.

Hydrogen line observations have also been used indirectly to calculate the mass of galaxies, to put limits on any changes over time of the universal gravitational constant and to study the dynamics of individual galaxies.

In cosmology[]

The line is of great interest in Big Bang cosmology because it is the only known way to probe the "dark ages" from recombination to reionization. Including the redshift, this line will be observed at frequencies from 200 MHz to about 9 MHz on Earth. It potentially has two applications. First, by mapping the intensity of redshifted 21 centimeter radiation it can, in principle, provide a very precise picture of the matter power spectrum in the period after recombination. Second, it can provide a picture of how the universe was reionized, as neutral hydrogen which has been ionized by radiation from stars or quasars will appear as holes in the 21 cm background.

However, 21 cm observations are very difficult to make. Ground-based experiments to observe the faint signal are plagued by interference from television transmitters and the ionosphere, so they must be made from very secluded sites with care taken to eliminate interference. Space based experiments, even on the far side of the Moon (where they would be sheltered from interference from terrestrial radio signals), have been proposed to compensate for this. Little is known about other effects, such as synchrotron emission and free–free emission on the galaxy. Despite these problems, 21 cm observations, along with space-based gravitational wave observations, are generally viewed as the next great frontier in observational cosmology, after the cosmic microwave background polarization.

Relevance to the search for non-human intelligent life[]

The Pioneer plaque, attached to the Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 spacecraft, portrays the hyperfine transition of neutral hydrogen and used the wavelength as a standard scale of measurement. For example, the height of the woman in the image is displayed as eight times 21 cm, or 168 cm. Similarly the frequency of the hydrogen spin-flip transition was used for a unit of time in a map to Earth included on the Pioneer plaques and also the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 probes. On this map, the position of the Sun is portrayed relative to 14 pulsars whose rotation period circa 1977 is given as a multiple of the frequency of the hydrogen spin-flip transition. It is theorized by the plaque's creators that an advanced civilization would then be able to use the locations of these pulsars to locate the Solar System at the time the spacecraft were launched.

The 21 cm hydrogen line is considered a favorable frequency by the SETI program in their search for signals from potential extraterrestrial civilizations. In 1959, Italian physicist Giuseppe Cocconi and American physicist Philip Morrison published "Searching for Interstellar Communications", a paper proposing the 21 cm hydrogen line and the potential of microwaves in the search for interstellar communications. According to George Basalla, the paper by Cocconi and Morrison "provided a reasonable theoretical basis" for the then-nascent SETI program.[7] Similarly, Pyotr Makovetsky proposed SETI use a frequency which is equal to either

- π × 1420.40575177 MHz ≈ 4.46233627 GHz

or

- 2π × 1420.40575177 MHz ≈ 8.92467255 GHz

Since π is an irrational number, such a frequency could not possibly be produced in a natural way as a harmonic, and would clearly signify its artificial origin. Such a signal would not be overwhelmed by the H I line itself, or by any of its harmonics.[8]

See also[]

- Chronology of the universe

- Dark Ages Radio Explorer

- H-alpha, the visible red spectral line with wavelength of 6562.8 ångstroms

- Hydrogen spectral series

- Rydberg formula

- Balmer series

- Schelling point

- Timeline of the Big Bang

References[]

- ^ The "I" is a roman numeral, so it is pronounced "H one".

- ^ Helmuth Hellwig; et al. (1970). "Measurement of the unperturbed hydrogen hyperfine transition frequency" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement. IM-19 (4).

- ^ Griffiths, D. J. (1982). "Hyperfine Splitting in the Ground State of Hydrogen". American Journal of Physics. 50 (8): 698–703. Bibcode:1982AmJPh..50..698G. doi:10.1119/1.12733.

- ^ Wiese, W. L.; Fuhr, J. R. (2009-06-24). "Accurate Atomic Transition Probabilities for Hydrogen, Helium, and Lithium". Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data. 38 (3): 565–720. doi:10.1063/1.3077727. ISSN 0047-2689.

- ^ Ewen, H. I.; Purcell, E. M. (September 1951). "Observation of a line in the galactic radio spectrum". Nature. 168 (4270): 356. Bibcode:1951Natur.168..356E. doi:10.1038/168356a0. S2CID 27595927.

- ^ Muller, C. A.; Oort, J. H. (September 1951). "The Interstellar Hydrogen Line at 1,420 Mc./sec., and an Estimate of Galactic Rotation". Nature. 168 (4270): 357–358. Bibcode:1951Natur.168..357M. doi:10.1038/168357a0. S2CID 32329393.

- ^ Basalla, George (2006). Civilized Life in the Universe. Oxford University Press. pp. 133–135. ISBN 978-0-19-517181-5.

- ^ Makovetsky, P. "Смотри в корень" (in Russian).

Cosmology[]

- Madau, P.; Meiksin, A.; Rees, M. J. (1997). "21-cm Tomography of the Intergalactic Medium at High Redshift". Astrophys. J. 475 (2): 429–444. arXiv:astro-ph/9608010. Bibcode:1997ApJ...475..429M. doi:10.1086/303549. S2CID 118239661.

- Ciardi, B.; Madau, P. (2003). "Probing Beyond the Epoch of Hydrogen Reionization with 21 Centimeter Radiation". Astrophys. J. 596 (1): 1–8. arXiv:astro-ph/0303249. Bibcode:2003ApJ...596....1C. doi:10.1086/377634. S2CID 10258589.

- Zaldarriaga, M.; Furlanetto, S.; Hernquist, L. (2004). "21 Centimeter Fluctuations from Cosmic Gas at High Redshifts". Astrophys. J. 608 (2): 622–635. arXiv:astro-ph/0311514. Bibcode:2004ApJ...608..622Z. doi:10.1086/386327. S2CID 119439713.

- Furlanetto, S.; Sokasian, A.; Hernquist, L. (2004). "Observing the Reionization Epoch Through 21 Centimeter Radiation". Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 347 (1): 187–195. arXiv:astro-ph/0305065. Bibcode:2004MNRAS.347..187F. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.07187.x. S2CID 6474189.

- Loeb, A.; Zaldarriaga, M. (2004). "Measuring the Small-Scale Power Spectrum of Cosmic Density Fluctuations Through 21 cm Tomography Prior to the Epoch of Structure Formation". Phys. Rev. Lett. 92 (21): 211301. arXiv:astro-ph/0312134. Bibcode:2004PhRvL..92u1301L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.211301. PMID 15245272. S2CID 30510359.

- Santos, M. G.; Cooray, A.; Knox, L. (2005). "Multifrequency analysis of 21 cm fluctuations from the Era of Reionization". Astrophys. J. 625 (2): 575–587. arXiv:astro-ph/0408515. Bibcode:2005ApJ...625..575S. doi:10.1086/429857. S2CID 15464776.

- Barkana, R.; Loeb, A. (2005). "Detecting the Earliest Galaxies Through Two New Sources of 21cm Fluctuations". Astrophys. J. 626 (1): 1–11. arXiv:astro-ph/0410129. Bibcode:2005ApJ...626....1B. doi:10.1086/429954. S2CID 7343629.

- Wang, Jingying; Xu, Haiguang; An, Tao; Gu, Junhua; Guo, Xueying; Li, Weitian; Wang, Yu; Liu, Chengze; Martineau-Huynh, Olivier; Wu, Xiang-Ping (2013-01-14). "Exploring the Cosmic Reionization Epoch in Frequency Space: An Improved Approach to Remove the Foreground in 21 cm Tomography". The Astrophysical Journal. 763 (2): 90. arXiv:1211.6450. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/763/2/90. ISSN 0004-637X.

External links[]

- Hydrogen physics

- Emission spectroscopy

- Radio astronomy

- Physical cosmology

- Astrochemistry

- Hydrogen