Imperial examination

| Imperial examination | |||

|---|---|---|---|

"Imperial examinations" in Traditional (top) and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||

| Chinese name | |||

| Traditional Chinese | 科舉 | ||

| Simplified Chinese | 科举 | ||

| Hanyu Pinyin | kējǔ | ||

| |||

| Vietnamese name | |||

| Vietnamese alphabet | khoa bảng khoa cử | ||

| Chữ Hán | 科榜 科舉 | ||

| Korean name | |||

| Hangul | 과거 | ||

| Hanja | 科擧 | ||

| |||

| Japanese name | |||

| Hiragana | かきょ | ||

| Kyūjitai | 科擧 | ||

| Shinjitai | 科挙 | ||

| |||

| Manchu name | |||

| Manchu script | ᡤᡳᡡ ᡰ᠊ᡳᠨ ᠰᡳᠮᠨᡝᡵᡝ | ||

| Möllendorff | giū žin simnere | ||

Chinese imperial examinations, or keju (lit. "subject recommendation"), were a civil service examination system in Imperial China for selecting candidates for the state bureaucracy. The concept of choosing bureaucrats by merit rather than birth started early in Chinese history but using written examinations as a tool of selection started in earnest during the mid-Tang dynasty. The system became dominant during the Song dynasty and lasted until it was abolished in the late Qing dynasty reforms in 1905.

The exams served to ensure a common knowledge of writing, the classics, and literary style among state officials. This common culture helped to unify the empire and the ideal of achievement by merit gave legitimacy to imperial rule. The examination system played a significant role in tempering the power of hereditary aristocracy and military authority, and the rise of a gentry class of scholar-bureaucrats.

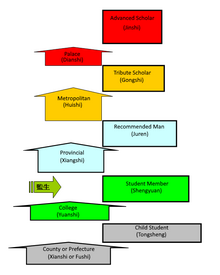

Starting with the Song dynasty, the system was regularized and developed into a roughly three-tiered ladder from local to provincial to court exams. The content was narrowed and fixed on texts of Neo-Confucian orthodoxy by the Ming dynasty, during which the highest degree, the jinshi (Chinese: 進士), became essential for the highest offices. On the other hand, holders of the basic degree, the shengyuan (生員), became vastly oversupplied, resulting in holders who could not hope for office. Wealthy families, especially from the merchant class, could opt into the system by educating their sons or purchasing degrees. In the late 19th century, critics blamed the examination system for stifling Chinese science and technical knowledge. China had about one civil licentiate per 1000 people. As many as two or three million men a year took the exams. With 99% failing, dissatisfaction was severe.[1]

The Chinese examination system also influenced neighboring countries. It existed in Japan (though briefly), Korea, Ryūkyū, as well as Vietnam. The Chinese examination system was introduced to the Western world in the reports of European missionaries and diplomats, and encouraged France, Germany, and the British East India Company to use a similar method to select prospective employees. Following the initial success in that company, the British government adopted a similar testing system for screening civil servants in 1855. Modeled after these previous adaptations, the United States established its own testing program for certain government jobs after 1883.

General history[]

Tests of skill such as archery contests have existed since the Zhou dynasty (or, more mythologically, Yao).[2] The Confucian characteristic of the later imperial exams was largely due to the reign of Emperor Wu of Han during the Han dynasty. Although some examinations did exist from the Han to the Sui dynasty, they did not offer an official avenue to government appointment, the majority of which were filled through recommendations based on qualities such as social status, morals, and ability.

The bureaucratic imperial examinations as a concept has its origins in the year 605 during the short lived Sui dynasty. Its successor, the Tang dynasty, implemented imperial examinations on a relatively small scale until the examination system was extensively expanded during the reign of Wu Zetian.[3] Included in the expanded examination system was a military exam, but the military exam never had a significant impact on the Chinese officer corps and military degrees were seen as inferior to their civil counterpart. The exact nature of Wu's influence on the examination system is still a matter of scholarly debate.

During the Song dynasty the emperors expanded both examinations and the government school system, in part to counter the influence of military aristocrats, increasing the number of degree holders to more than four to five times that of the Tang. From the Song dynasty onward, the examinations played the primary role in selecting scholar-officials, who formed the literati elite of society. However the examinations co-existed with other forms of recruitment such as direct appointments for the ruling family, nominations, quotas, clerical promotions, sale of official titles, and special procedures for eunuchs. The regular higher level degree examination cycle was decreed in 1067 to be three years but this triennial cycle only existed in nominal terms. In practice both before and after this, the examinations were irregularly implemented for significant periods of time: thus, the calculated statistical averages for the number of degrees conferred annually should be understood in this context. The jinshi exams were not a yearly event and should not be considered so; the annual average figures are a necessary artifact of quantitative analysis.[4] The operations of the examination system were part of the imperial record keeping system, and the date of receiving the jinshi degree is often a key biographical datum: sometimes the date of achieving jinshi is the only firm date known for even some of the most historically prominent persons in Chinese history.

A brief interruption to the examinations occurred at the beginning of the Mongol Yuan dynasty in the 13th century, but was later brought back with regional quotas which favored the Mongols and disadvantaged Southern Chinese. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the system contributed to the narrow and focused nature of intellectual life and enhanced the autocratic power of the emperor. The system continued with some modifications until its abolition in 1905 during the last years of the Qing dynasty. The modern examination system for selecting civil servants also indirectly evolved from the imperial one.[5]

| Dynasty | Exams held | Jinshi graduates |

|---|---|---|

| Tang (618–907) | 6,504 | |

| Song (960–1279) | 118 | 38,517 |

| Yuan (1271–1368) | 16 | 1,136 |

| Ming (1368–1644) | 89 | 24,536 |

| Qing (1636–1912) | 112 | 26,622 |

Precursors[]

Han dynasty[]

Candidates for offices recommended by the prefect of prefecture were examined by the Ministry of Rites and then presented to the emperor. Some candidates for clerical positions would be given a test to determine whether they could memorize nine thousand Chinese characters.[6] The tests administered during the Han dynasty did not offer formal entry into government posts. Recruitment and appointment in the Han dynasty were primarily through recommendations by aristocrats and local officials. Recommended individuals were also primarily aristocrats. In theory, recommendations were based on a combination of reputation and ability but it is not certain how well this worked in practice. Oral examinations on policy issues were sometimes conducted personally by the emperor himself during Western Han times.[7]

In 165 BC Emperor Wen of Han introduced recruitment to the civil service through examinations, however these did not heavily emphasize Confucian material. Previously, potential officials never sat for any sort of academic examinations.[8]

Emperor Wu of Han's early reign saw the creation of a series of posts for academicians in 136 BC.[9] Ardently promoted by Dong Zhongshu, the Taixue and Imperial examination came into existence by recommendation of Gongsun Hong, chancellor under Wu.[10] Officials would select candidates to take part in an examination of the Confucian classics, from which Emperor Wu would select officials to serve by his side.[11] Gongsun intended for the Taixue's graduates to become imperial officials but they usually only started off as clerks and attendants,[12] and mastery of only one canonical text was required upon its founding, changing to all five in the Eastern Han.[13][14] Starting with only 50 students, Emperor Zhao expanded it to 100, Emperor Xuan to 200, and Emperor Yuan to 1000.[15]

While the examinations expanded under the Han, the number of graduates who went on to hold office were few. The examinations did not offer a formal route to commissioned office and the primary path to office remained through recommendations. Though connections and recommendations remained more meaningful than the exam, the initiation of the examination system by Emperor Wu was crucial for the Confucian nature of later imperial examinations. During the Han dynasty, these examinations were primarily used for the purpose of classifying candidates who had been specifically recommended. Even during the Tang dynasty the quantity of placements into government service through the examination system only averaged about nine persons per year, with the known maximum being less than 25 in any given year.[11]

Three Kingdoms[]

The first standardized method of recruitment in Chinese history was introduced during the Three Kingdoms period in the Kingdom of Wei. It was called the nine-rank system. In the nine-rank system, each office was given a rank from highest to lowest in descending order from one to nine. Imperial officials were responsible for assessing the quality of the talents recommended by local elites. The criteria for recruitment included qualities such as morals and social status, which in practice meant that influential families monopolized all high ranking posts while men of poorer means filled the lower ranks.[16][17]

The local zhongzheng (lit. central and impartial) officials assessed the status of households or families in nine categories; only the sons of the fifth categories and above were entitled to offices. The method obviously contradicted the ideal of meritocracy. It was, however, convenient in a time of constant wars among the various contending states, all of them relying on an aristocratic political and social structure. For nearly three hundred years, noble young men were afforded government higher education in the Imperial Academy and carefully prepared for public service. The Jiupin guanren fa was closely related to this kind of educational practice and only began to decline after the second half of the sixth century.[18]

— Thomas H.C. Lee

History by dynasty[]

Sui dynasty (581–618)[]

The Sui dynasty continued the tradition of recruitment through recommendation but modified it in 587 with the requirement for every prefecture to supply three scholars a year. In 599, all capital officials of rank five and above were required to make nominations for consideration in several categories.[16]

During the Sui dynasty, examinations for "classicists" (mingjing ke) and "cultivated talents" (xiucai ke) were introduced. Classicists were tested on the Confucian canon, which was considered an easy task at the time, so those who passed were awarded posts in the lower rungs of officialdom. Cultivated talents were tested on matters of statecraft as well as the Confucian canon. In AD 607, Emperor Yang of Sui established a new category of examinations for the "presented scholar" (jinshike 进士科). These three categories of examination were the origins of the imperial examination system that would last until 1905. Consequently, the year 607 is also considered by many to be the real beginning of the imperial examination system. The Sui dynasty was itself short lived however and the system was not developed further until much later.[17]

The imperial examinations did not significantly shift recruitment selection in practice during the Sui dynasty. Schools at the capital still produced students for appointment. Inheritance of official status was also still practiced. Men of the merchant and artisan classes were still barred from officialdom. However the reign of Emperor Wen of Sui did see much greater expansion of government authority over officials. Under Emperor Wen, all officials down to the district level had to be appointed by the Department of State Affairs in the capital and were subjected to annual merit rating evaluations. Regional Inspectors and District Magistrates had to be transferred every three years and their subordinates every four years. They were not allowed to bring their parents or adult children with them upon reassignment of territorial administration. The Sui did not establish any hereditary kingdoms or marquisates of the Han sort. To compensate, nobles were given substantial stipends and staff. Aristocratic officials were ranked based on their pedigree with distinctions such as "high expectations", "pure", and "impure" so that they could be awarded offices appropriately.[19]

Tang dynasty (618–907)[]

The Tang dynasty and the Zhou interregnum of Empress Wu (Wu Zetian) expanded examinations beyond the basic process of qualifying candidates based on questions of policy matters followed by an interview.[20] Oral interviews as part of the selection process were theoretically supposed to be an unbiased process, but in practice favored candidates from elite clans based in the capitals of Chang'an and Luoyang (speakers of solely non-elite dialects could not succeed).[21]

Under the Tang, six categories of regular civil-service examinations were organized by the Department of State Affairs and held by the Ministry of Rites: cultivated talents, classicists, presented scholars, legal experts, writing experts, and arithmetic experts. Emperor Xuanzong of Tang also added categories for Daoism and apprentices. The hardest of these examination categories, the presented scholar jinshi degree, became more prominent over time until it superseded all other examinations. By the late Tang the jinshi degree became a prerequisite for appointment into higher offices. Appointments by recommendation were also required to take examinations.[16]

The examinations were carried out in the first lunar month. After the results were completed, the list of results was submitted to the Grand Chancellor, who had the right to alter the results. Sometimes the list was also submitted to the Secretariat-Chancellery for additional inspection. The emperor could also announce a repeat of the exam. The list of results was then published in the second lunar month.[17]

Classicists were tested by being presented phrases from the classic texts. Then they had to write the whole paragraph to complete the phrase. If the examinee was able to correctly answer five of ten questions, they passed. This was considered such an easy task that a 30-year-old candidate was said to be old for a classicist examinee, but young to be a jinshi. An oral version of the classicist examination known as moyi also existed but consisted of 100 questions rather than just ten. In contrast, the jinshi examination not only tested the Confucian classics, but also history, proficiency in compiling official documents, inscriptions, discursive treatises, memorials, and poems and rhapsodies. Because the number of jinshi graduates were so low they acquired great social standing in society. The judicial, arithmetic, and clerical examinations were also held but these graduates only qualified for their specific agencies.[17]

Candidates who passed the exam were not automatically granted office. They still had to pass a quality evaluation by the Ministry of Rites, after which they were allowed to wear official robes.[17]

Zhou interregnum[]

Wu Zetian's reign was a pivotal moment for the imperial examination system.[11] The reason for this was because up until that point, the Tang rulers had all been male members of the Li family. Wu Zetian, who officially took the title of emperor in 690, was a woman outside the Li family who needed an alternative base of power. Reform of the imperial examinations featured prominently in her plan to create a new class of elite bureaucrats derived from humbler origins. Both the palace and military examinations were created under Wu Zetian.[17]

In 655, Wu Zetian graduated 44 candidates with the jìnshì degree (進士), and during one seven-year period the annual average of exam takers graduated with a jinshi degree was greater than 58 persons per year. Wu lavished favors on the newly graduated jinshi degree-holders, increasing the prestige associated with this path of attaining a government career, and clearly began a process of opening up opportunities to success for a wider population pool, including inhabitants of China's less prestigious southeast area.[11] Most of the Li family supporters were located to the northwest, particularly around the capital city of Chang'an. Wu's progressive accumulation of political power through enhancement of the examination system involved attaining the allegiance of previously under-represented regions, alleviating frustrations of the literati, and encouraging education in various locales so even people in the remote corners of the empire would study to pass the imperial exams. These degree holders would then become a new nucleus of elite bureaucrats around which the government could center itself.[22]

In 681, a fill in the blank test based on knowledge of the Confucian classics was introduced.[23]

In 693, Wu Zetian's government further expanded the civil service examination system by allowing commoners and gentry previously disqualified by their non-elite backgrounds to take the tests.[24] Examples of officials whom she recruited through her reformed examination system include Zhang Yue, Li Jiao, and Shen Quanqi.[25]

Despite the rise in importance of the examination system, the Tang society was still heavily influenced by aristocratic ideals, and it was only after the ninth century that the situation changed. As a result, it was common for candidates to visit examiners before the examinations in order to win approval. The aristocratic influence declined after the ninth century, when the examination degree holders also increased in numbers. They now began to play a more decisive role in the Court. At the same time, a quota system was established which could enhance the equitable representation, geographically, of successful candidates.[26]

— Thomas H.C. Lee

From 702 on, the names of examinees were hidden to prevent examiners from knowing who was tested. Prior to this, it was even a custom for candidates to present their examiner with their own literary works in order to impress him.[17]

Tang restoration[]

Sometime between 730 and 740, after the Tang restoration, a section requiring the composition of original poetry (including both shi and fu) was added to the tests, with rather specific set requirements: this was for the jinshi degree, as well as certain other tests. The less-esteemed examinations tested for skills such as mathematics, law, and calligraphy. The success rate on these tests of knowledge on the classics was between 10 and 20 percent, but for the thousand or more candidates going for a jinshi degree each year in which it was offered, the success rate for the examinees was only between 1 and 2 percent: a total of 6504 jinshi were created during course of the Tang dynasty (an average of only about 23 jinshi awarded per year).[23] After 755, up to 15 percent of civil service officials were recruited through the examinations.[27]

During the early years of the Tang restoration, the following emperors expanded on Wu's policies since they found them politically useful, and the annual averages of degrees conferred continued to rise. This led to the formation of new court factions consisting of examiners and their graduates. With the upheavals which later developed and the disintegration of the Tang empire into the "Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period", the examination system gave ground to other traditional routes to government positions and favoritism in grading reduced the opportunities of examinees who lacked political patronage.[22] Ironically this period of fragmentation resulted in the utter destruction of old networks established by elite families that had ruled China throughout its various dynasties since its conception. With the disappearance of the old aristocracy, Wu's system of bureaucrat recruitment once more became the dominant model in China, and eventually coalesced into the class of nonhereditary elites who would become known to the West as "mandarins," in reference to Mandarin, the dialect of Chinese employed in the imperial court.[28]

Song dynasty (960–1279)[]

In the Song dynasty (960–1279) the imperial examinations became the primary method of recruitment for official posts. More than a hundred palace examinations were held during the dynasty, resulting in a greater number of jinshi degrees rewarded.[16] The examinations were opened to adult Chinese males, with some restrictions, including even individuals from the occupied northern territories of the Liao and Jin dynasties.[29] Many individuals of low social status were able to rise to political prominence through success in the imperial examination. Prominent officials who went through the imperial examinations include Wang Anshi, who proposed reforms to make the exams more practical, and Zhu Xi, whose interpretations of the Four Classics became the orthodox Neo-Confucianism which dominated later dynasties. Two other prominent successful entries into politics through the examination system were Su Shi and his brother Su Zhe: both of whom became political opponents of Wang Anshi. The process of studying for the examination tended to be time-consuming and costly, requiring time to spare and tutors. Most of the candidates came from the numerically small but relatively wealthy land-owning scholar-official class.[30]

The examination hierarchy was formally divided into prefectural, metropolitan, and palace examinations. The prefectural examination was held on the 15th day of the eighth lunar month. Graduates of the prefectural examination were then sent to the capital for metropolitan examination, which took place in Spring, but had no fixed date. Graduates of the metropolitan examination were then sent to the palace examination.[17]

Since 937, by the decision of the Emperor Taizu of Song, the palace examination was supervised by the emperor himself. In 992, the practice of anonymous submission of papers during the palace examination was introduced; it was spread to the departmental examinations in 1007, and to the prefectural level in 1032. From 1037 on, it was forbidden for examiners to supervise examinations in their home prefecture. Examiners and high officials were also forbidden from contacting each other prior to the exams. The practice of recopying papers in order to prevent revealing the candidate's calligraphy was introduced at the capital and departmental level in 1015, and in the prefectures in 1037.[31] Statistics indicate that the Song imperial government degree-awards eventually more than doubled the highest annual averages of those awarded during the Tang dynasty, with 200 or more per year on average being common, and at times reaching a per annum figure of almost 240.[22] By 1050, about half of the 12,700 officials in the employ of the Song civil service were exam graduates.[27]

In 1071, Emperor Shenzong of Song (r. 1067–1085) abolished the classicist as well as various other examinations on law and arithmetics. The jinshi examination became the primary gateway to officialdom. Judicial and classicist examinations were revived shortly after. However the judicial examination was classified as a special examination and not many people took the classicist examination. The oral version of the classicist exam was abolished. Other special examinations for household and family member of officials, Minister of Personnel, and subjects such as history as applied to current affairs (shiwu ce Policy Questions), translation, and judicial matters were also administered by the state. Policy Questions became an essential part of following examinations. An exam called the cewen which focused on contemporary matters such as politics, economics, and military affairs was introduced.[17][32]

The Song also saw the introduction of a new examination essay, that of jing yi; (exposition on the meaning of the Classics). This required candidates to compose a logically coherent essay by juxtaposing quotations from the Classics or sentences of similar meaning to certain passages. This reflected the stress the Song placed on creative understanding of the Classics. It would eventually develop into the so-called ‘eight-legged essays’ essays (bagu wen ) that gave the defining character to the Ming and Qing examinations.[33]

— Thomas H.C. Lee

Various reforms or attempts to reform the examination system were made during the Song dynasty by individuals such as Fan Zhongyan, Zhu Xi, and by Wang Anshi. Wang and Zhu successfully argued that poems and rhapsodies should be excluded from the examinations because they were of no use to administration or cultivation of virtue. The poetry section of the examination was removed in the 1060s. Fan's memorial to the throne initiated a process which lead to major educational reform through the establishment of a comprehensive public school system.[34][17]

Liao dynasty (907–1125)[]

The Khitans who ruled the Liao dynasty only held imperial examinations for regions with large Chinese populations. The Liao examinations focused on lyric-meter poetry and rhapsodies. The Khitans themselves did not take the exams until 1115 when it became an acceptable avenue for advancing their careers.[35]

Jin dynasty (1115–1234)[]

The Jurchens of the Jin dynasty held two separate examinations to accommodate their former Liao and Song subjects. In the north examinations focused on lyric-meter poetry and rhapsodies while in the south, Confucian Classics were tested. During the reign of Emperor Xizong of Jin (r. 1135–1150), the contents of both examinations were unified and examinees were tested on both genres. Emperor Zhangzong of Jin (r. 1189–1208) abolished the prefectural examinations. Emperor Shizong of Jin (r. 1161–1189) created the first examination conducted in the Jurchen language, with a focus on political writings and poetry. Graduates of the Jurchen examination were called "treatise graduates" (celun jinshi) to distinguish them from the regular Chinese jinshi.[17]

Yuan dynasty (1279–1368)[]

Imperial examinations were ceased for a time with the defeat of the Song in 1279 by Kublai Khan and his Yuan dynasty. One of Kublai's main advisers, Liu Bingzhong, submitted a memorial recommending the restoration of the examination system: however, this was not done.[36] Kublai ended the imperial examination system, as he believed that Confucian learning was not needed for government jobs.[37] Also, Kublai was opposed to such a commitment to the Chinese language and to the Chinese scholars who were so adept at it, as well as its accompanying ideology: he wished to appoint his own people without relying on an apparatus inherited from a newly conquered and sometimes rebellious country.[38] The discontinuation of the exams had the effect of reducing the prestige of traditional learning, reducing the motivation for doing so, as well as encouraging new literary directions not motivated by the old means of literary development and success.[39]

The examination system was revived in 1315, with significant changes, during the reign of Ayurbarwada Buyantu Khan. The new examination system organized its examinees into regional categories in a way which favored Mongols and severely disadvantaged Southern Chinese. A quota system both for number of candidates and degrees awarded was instituted based on the classification of the four groups, those being the Mongols, their non-Han allies (Semu-ren), Northern Chinese, and Southern Chinese, with further restrictions by province favoring the northeast of the empire (Mongolia) and its vicinities.[40] A quota of 300 persons was fixed for provincial examinations with 75 persons from each group. The metropolitan exam had a quota of 100 persons with 25 persons from each group. Candidates were enrolled on two lists with the Mongols and Semu-ren located on the left and the Northern and Southern Chinese on the right. Examinations were written in Chinese and based on Confucian and Neo-Confucian texts but the Mongols and Semu-ren received easier questions to answer than the Chinese. Successful candidates were awarded one of three ranks. All graduates were eligible for official appointment.[17]

The Yuan decision to use Zhu Xi’s classical scholarship as the examination standard was critical in enhancing the integration of the examination system with Confucian educational experience. Both Chinese and non-Chinese candidates were recruited separately, to guarantee that non-Chinese officials could control the government, but this also furthered Confucianisation of the conquerors.[33]

— Thomas H.C. Lee

Under the revised system the yearly averages for examination degrees awarded was about 21.[40] The way in which the four regional racial categories were divided tended to favor the Mongols, Semu-ren, and North Chinese, despite the South Chinese being by far the largest portion of the population. The 1290 census figures record some 12,000,000 households (about 48% of the total Yuan population) for South China, versus 2,000,000 North Chinese households, and the populations of Mongols and Semu-ren were both less.[40] While South China was technically allotted 75 candidates for each provincial exam, only 28 Han Chinese from South China were included among the 300 candidates, the rest of the South China slots (47) being occupied by resident Mongols or Semu-ren, although 47 "racial South Chinese" who were not residents of South China were approved as candidates.[41]

Ming dynasty (1368–1644)[]

The Ming dynasty (1368–1644) retained and expanded the system it inherited. The Hongwu Emperor was initially reluctant to restart the examinations, considering their curriculum to be lacking in practical knowledge. In 1370 he declared that the exams would follow the Neo-Confucian canon put forth by Zhu Xi in the Song dynasty: the Four Books, discourses, and political analysis. Then he abolished the examinations two years later because he preferred appointment by referral. In 1384, the examinations were revived again, however in addition to the Neo-Confucian canon, Hongwu added another portion to the exams to be taken by successful candidates five days after the first exam. These new exams emphasized shixue (practical learning), including subjects such as law, mathematics, calligraphy, horse riding, and archery. The emperor was particularly adamant about the inclusion of archery, and for a few days after issuing the edict, he personally commanded the Guozijian and county-level schools to practice it diligently.[42][43] As a result of the new focus on practical learning, from 1384 to 1756/7, all provincial and metropolitan examinations incorporated material on legal knowledge and the palace examinations included policy questions on current affairs.[44] The first palace examination of the Ming dynasty was held in 1385.[17]

Provincial and metropolitan exams were organized in three sessions. The first session consisted of three questions on the examinee's interpretation of the Four Books, and four on the Classics corpus. The second session took place three days later, and consisted of a discursive essay, five critical judgments, and one in the style of an edict, an announcement and a memorial. Three days after that, the third session was held, consisting of five essays on the Classics, historiography, and contemporary affairs. The palace exam was just one session, consisting of questions on critical matters in the Classics or current affairs. Written answers were expected to follow a predefined structure called the eight-legged essay which consisted of the eight parts opening, amplification, preliminary exposition, initial argument, central argument, latter argument, final argument, and conclusion. The length of the essay ranged between 550 and 700 characters. Gu Yanwu considered the eight-legged essay to be worse than the book burning of Qin Shi Huang and his burying alive of 460 Confucian scholars.[17]

The content of the examinations in the Ming and Qing times remained very much the same as that in the Song, except that literary composition was now widened to include government documents. The most important was the weight given to eight-legged essays. As a literary style, they are constructed on logical reasoning for coherent exposition. However, as the format evolved, they became excessively rigid, to ensure fair grading. Candidates often only memorised ready essays in the hope that the ones they memorised might be the examination questions. Since all questions were taken from the Classics, there were just so many possible passages that the examiners could use for questions. More often than not, the questions could be a combination of two or more totally unrelated passages. Candidates could be at a complete loss as to how to make out their meaning, let alone writing a logically coherent essay. This aroused strong criticism, but the use of the style remained until the end of the examination system.[33]

— Thomas H.C. Lee

The Hanlin Academy played a central role in the careers of examination graduates during the Ming dynasty. Graduates of the metropolitan exam with honors were directly appointed senior compiler in the Hanlin Academy. Regular metropolitan exam graduates were appointed junior compilers or examining editors. In 1458, appointment in the Hanlin Academy and the Grand Secretariat was restricted to jinshi graduates. Posts such as minister or vice minister of rites or right vice ministers of personnel were also restricted to jinshi graduates. The training jinshi graduates underwent in the Hanlin Academy allowed them insight into a wide range of central government agencies. Ninety percent of Grand Chancellors during the Ming dynasty were jinshi degree holders.[17]

The Neo-Confucian orthodoxy became the new guideline for literati learning, narrowing the way in which they could politically and socially interpret the Confucian canon. At the same time, commercialization of the economy and booming population growth resulted in an inflation of the number of degree candidates at the lower levels. The Ming bureaucracy did not increase degree quotas in proportion to the increased population. Near the end of the Ming dynasty, in 1600, there were roughly 500,000 shengyuan in a population of 150 million, that is, one per 300 people. This trend of booming population but artificial limitation of degrees awarded continued into the Qing dynasty, when during the mid-19th century, the ratio of shengyuan to population had shrunk to one per each thousand people. Access to government office became not only extremely difficult, but officials also became more orthodox in their thinking. The higher and more prestigious offices were still dominated by jinshi degree-holders, similar to the Song dynasty, but tended to come from elite families.[45]

The social background of metropolitan graduates also narrowed as time went on. In the early years of the Ming dynasty only 14 percent of metropolitan graduates came from families that had a history of providing officials, while in the last years of the Ming roughly 60 percent of metropolitan exam graduates came from established elite families.

Qing dynasty (1636–1912)[]

The ambition of Hong Taiji, the first emperor of the Qing dynasty, was to use the examinations to foster a cadre of Manchu Bannermen who were both martial and literate to administer the government. He initiated the first exam for bannermen in 1638, offered in both Manchu and Chinese, even before his troops took Beijing in 1644. But the Manchu bannermen had no time or money to prepare for the exams, especially since they could gain advancement on the battlefield, and the dynasty went on to rely on both Manchu and Han Chinese officials chosen through the system inherited with minor adaptation from the Ming. [46] During the dynasty a total of 26,747 jinshi degrees were earned in 112 examinations held over the 261 years 1644–1905, an average of 238.8 jinshi degrees conferred per examination.[47]

Racial quotas were placed on the number of graduates permitted. In the early Qing period, a 4:6 Manchu to Han quota was placed on the palace examination, and was in effect until 1655. Separate examinations were held for bannermen from 1652 to 1655 with a ten-point racial quota of 4:2:4 for Manchus, Mongols, and Han Chinese. In 1651, "translation" examinations were implemented for bannermen, however the purpose of these exams was not to create translators, but to service those Manchus and bannermen who did not understand Classical Chinese. During the reign of the Qianlong Emperor (1736–95), Manchus and Mongols were encouraged to take the examinations in Classical Chinese. The translation examination was abolished in 1840 because there weren't enough candidates to justify it. After 1723, Han Chinese graduates of the palace examination were required to learn the Manchu language. Bilingualism in Chinese and Manchu languages was favored in the bureaucracy and people who fulfilled the language requirements were given preferential appointments. For example, in 1688, a candidate from Hangzhou who was able to answer policy questions at the palace examination in both Chinese and Manchu was appointed as compiler at the Hanlin Academy, despite finishing bottom of the second tier of jinshi graduates. Ethnic minorities such as the Peng people in Jiangxi Province were given a quota of 1:50 for the shengyuan degree to encourage them to settle down and give up their nomadic way of life. In 1767, a memorial from Guangxi Province noted that some Han Chinese took advantage of the ethnic quotas to become shengyuan and that it was hard to verify who was a native. In 1784, quotas were recommended for Muslims to incorporate them into mainstream society. In 1807, a memorial from Hunan Province requested higher quotas for Miao people so that they would not have to compete with Han Chinese candidates.[48]

Taiping Heavenly Kingdom (1851–1864)[]

The Chinese Christian Taiping Heavenly Kingdom was created in rebellion against the Qing dynasty led by a failed examination candidate Hong Xiuquan, which established its capital in Nanjing in 1851. Following the imperial example, the Taipings held exams starting in 1851.[49] They replaced the Confucian Classes, however, with the Taiping Bible, the Old and New Testaments as edited by Hong. Candidates were expected to write eight-legged essays using quotations.[50]

In 1853, women were for the first time in Chinese history able to become examination candidates. Fu Shanxiang took the exam and became the first (and last) female zhuangyuan in Chinese history.[51]

Decline and abolition[]

By the 1830s and 1840s, proposals emerged from officials calling for reforms to the Imperial Examinations to include Western technology. In 1864, Li Hongzhang submitted proposals to add a new subject into the Imperial examinations involving Western technology, that scholars may focus their efforts entirely on this. A similar proposal was tabled by Feng Guifen in 1861 and Ding Richang (mathematics and science) in 1867. In 1872, and again in 1874, Shen Baozhen submitted proposals to the throne for the reform of the Imperial Examinations to include Mathematics. Shen also proposed the abolition of the military examinations, which were based on obsolete weaponry such as archery. He proposed the idea that Tongwen Guan students who performed well in mathematics could be directly appointed to the Zongli Yamen as if they were Imperial examination graduates. Li Hongzhang, in an 1874 memorial, tabled the concept of "Bureaus of Western Learning" (洋学局) in coastal provinces, participation in which was to be accorded the honour of Imperial examination degrees.[52][53] In 1888, the Imperial examinations was expanded to include the subject of international commerce.[54]

With the military defeats in the 1890s and pressure to develop a national school system, reformers such as Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao called for abolition of the exams, and the Hundred Days' Reform of 1898 proposed a set of modernizations. After the Boxer Rebellion, the government drew up plans to reform under the name of New Policies. Reformers memorialized the throne to abolish the system. The key sponsors were Yuan Shikai, Yin Chang, and Zhang Zhidong (Chang Chih-tung). On 2 September 1905, the throne ordered the examination system be discontinued, beginning at the first level in 1905. The new system provided equivalents to the old degrees; a bachelor's degree, for instance, would be considered equivalent to the xiu cai.[55][56][57][58][17]

Those who had at least the degree of shengyuan remained fairly well off since they retained their social status. Older students who had failed to even become shengyuan were more damaged because they could not easily absorb new learning, were too proud to turn to commerce, and too weak for physical labor.[59]

Impact[]

Transition to scholar-bureaucracy[]

The original purpose of the imperial examinations as they were implemented during the Sui dynasty was to strike a blow against the hereditary aristocracy and to centralize power around the emperor. The era preceding the Sui dynasty, the period of Northern and Southern dynasties, was a golden age for the Chinese aristocracy. The power they wielded seriously constrained the emperor's ability to exercise his power in court, especially when it came to appointing officials. The Sui emperor created the imperial examinations to bypass and mitigate aristocratic interests. This was the origin of the Chinese examination system.[60]

Although quite a few Northern Song families or lineages succeeded in producing high officials over several generations, none could begin to rival the great families of the Six Dynasties and Tang in longevity, prestige, or perhaps even power. Most important, the promise of the examinations transformed learning from an elite concern to a preoccupation. Education became less the domain of scholarly families comprising one portion of elite society and more an activity urged upon academically promising boys and young men throughout elite society.[61]

— John W. Chaffee

The short lived Sui dynasty was soon replaced by the Tang, who built on the examination system. The emperor placed the palace exam graduates, the jinshi, in important government posts, where they came into conflict with hereditary elites. During the reign of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (713-56), about a third of the Grand Chancellors appointed were jinshi, but by the time of Emperor Xianzong of Tang (806-21), three fifths of the Grand Chancellors appointed were jinshi. This change in the way government was organized dealt a real blow to the aristocrats, but they did not sit idly by and wait to become obsolete. Instead they themselves entered the examinations to gain the privileges associated with it. By the end of the dynasty, the aristocratic class had produced 116 jinshi, so that they remained a significant influence in the government. Hereditary privileges were also not completely done away with. The sons of high ministers and great generals had the right to hold minor offices without taking the examinations. In addition, the number of graduates were not only small, but also formed their own clique in the government based around the examiners and the men they passed. In effect the graduates became another interest group the emperor had to contend with. This problem was greatly mitigated by the increase in candidates and graduates during the Song dynasty, made possible by its robust economy. Since the entire upper echelon of the Song dynasty was filled by jinshi, and imperial clan members were barred from posts of substance,[62] there was no longer any conflict of the type relating to different preparatory backgrounds. Efforts were made to break the link between examiner and examinee, removing another factor contributing to the formation of scholar bureaucrat cliques. While the influence of certain scholar officials never disappeared, they no longer held any influence in organizing men.[63]

... the true characteristic of the Song political system was not autocracy but "scholar-official (shidafu) government," made possible by the existence of the examination system as a means of validating political authority. Over the long run, the emperor shifted from being a figure with administrative power to one with symbolic power, tightly constrained by the system he was part of, even if he did not always act according to the ideals his ministers urged upon him; the emperor was not the top of a pyramid but the keystone in an arch, whose successful functioning depended on his staying in his place.[64]

— Peter K. Bol

Song Taizong possessed all of his older brother’s ambitions and suspicions but almost none of his positive qualities. As a child he had no friends, and as an adult he was a poor leader of men. Liu Jingzhen has characterized him as self-confident and self-reliant, but I think a more accurate assessment would be arrogant and insecure. All of these qualities, combined with an energetic constitution, led Taizong to attempt to read every document and make every decision necessary for the operations of government. The immense quantities of paper generated by the Song bureaucracy inevitably defeated him in this project, though he continued heroically trying to master it until his death. The central irony of Taizong’s reign was that the more he succeeded in centralizing the power of government and increasing the authority of the emperor, the less any individual emperor, no matter how energetic, could control that power by himself. Taizong thus unintentionally presided over the shift of the de jure nearly absolute imperial power to the de facto control of a rapidly professionalizing bureaucracy.[65]

— Peter Lorge

Subordination of the military[]

Although there was a military version of the exam, it was neglected by the government. The importance of the regular imperial examinations in governance had the effect of subordinating the military to civil government. By the time of the Song dynasty, the two highest military posts of Minister of War and Chief of Staff were both reserved for civil servants. It became routine for civil officials to be appointed as front-line commanders in the army. The highest rank for a dedicated military career was reduced to unit commander. To further reduce the influence of military leaders, they were routinely reassigned at the end of a campaign, so that no lasting bond occurred between commander and soldier. The policy of appointing civil officials as ad hoc military leaders was maintained by both the Ming and Qing dynasties after the initial phase of conquest. Successful commanders entrenched solely in the military tradition such as Yue Fei were viewed with distrust and apprehension. He was eventually executed by the Song government despite successfully leading Song forces against the Jin dynasty. It's possible that foreigners also looked down on Chinese military men. In 1042, the general Fan Zhongyan refused a military title because he thought it would demean him in the eyes of the Tibetans and Tanguts.[66] Although it negatively impacted the military's performance at times, the new relationship between the civil and military sectors of the government avoided the endemic military coups of preceding dynasties for the rest of imperial Chinese history.[67]

Education[]

During the Tang period, a set curricular schedule took shape where the three steps of reading, writing, and the composition of texts had to be learnt before students could enter state academies.[68] As the number of graduates increased, competition for government posts became more fierce. Whereas at the beginning of the Tang dynasty, there were few jinshi, during the Song dynasty, there were more than the government needed. Several reforms to education were suggested to thin the number of candidates and improve their quality. In 1044, Han Qi, Fan Zhongyan, Ouyang Xiu, and Song Qi implemented the Qingli Reforms, which included hiring experts in the classics to teach at government schools, setting up schools in every prefecture, and requiring every candidate to have attended the prefectural school for at least 300 days to qualify for the prefectural exam. Prior to the Qingli Reforms, the role of the state was limited to supporting a few institutions, such as in 1022 when the government granted a prefectural school in Yanzhou with 151 acres of land. The Qingli Reforms were abandoned after only one year.[69]

By the end of the Northern Song... government schools connected in a hierarchical empire-wide system, but there was a high degree of organizational uniformity as well. Prefectural school preceptorships became respected posts in local administration which, as far as we can tell, were routinely filled; educational support fields and student support provisions became the rule rather than the exception; and to cope with the rising demand of schooling, school entrance examinations became common.[70]

— John W. Chaffee

While the Qingli Reforms failed, the ideal of a state wide education system was taken up by Wang Anshi (1021–86), who proposed as part of his New Policies that examinations alone were not enough to select talent. His answer to the glut of graduates was to found new schools (shuyuan) for the selection of officials, with the ultimate goal of replacing the examinations altogether by selecting officials directly from the school's students. The government expanded the Guozijian (National University) and ordered each circuit to grant land to schools and to hire supervising teachers for them. In 1076, a special examination for teachers was introduced.[71] Implementation of the reforms was uneven and slow. Of the 320 prefectures, only 53 had prefectural schools with supervising teachers by 1078 and only a few were given the ordered allotment of land. Wang died and his reforms languished until the early 12th century when Emperor Huizong of Song injected more resources into the national education project. Schools received approximately 1.5 million acres of land taken from the state granaries. In 1104, students started being processed up the three-colleges (Three Hall) ranking system from the county school to the Guozijian for direct appointment in the bureaucracy. At its height the Song education system counted roughly 200,000 students in total, or approximately 0.2% of its one hundred million people. The schools went into decline starting from the Southern Song period (1127–1279) after the loss of the north to the Jin dynasty. The government was reluctant to fund them because they did not create immediate profits and as a result, cuts were made in teaching personnel, and the national university itself was reduced in size. Schools in imperial China never recovered from the decline starting from the Southern Song. For the rest of China's dynastic history, government funded academies functioned primarily as gateways to the examination system, and did not offer any real instruction to students. Functionally they were not schools but rather preparatory institutions for the examinations.[72] Wang's goal of replacing the examinations was never realized. Although Wang's reforms fell short of their mark, they launched the first state led initiative to regulate the day to day education of its subjects through the appointment of teachers and funding of schools.[73]

The major exception was in the 1140s when the court played an active role in the reconstruction of schools and made repeated efforts to get them all staffed with degree-holding preceptors... Following this period, the central government's involvement in government schools seems to have ceased. According to contemporary complaints, the schools deteriorated in quality and were subjected to various abuses such as heterodox teaching, no teaching at all, and loss of revenue.[74]

— John W. Chaffee

Primary education was relegated to private schools founded by kinship clusters during the Ming dynasty, although private teachers for individual households remained popular. Some schools were charity projects of the imperial government. The government also funded specialized schools for each of the Eight Banners to teach the Manchu language and Chinese. None of these institutions had a standardized curriculum or age of admission.[68]

Surplus graduates[]

The problem of surplus graduates became especially acute starting from the 18th century. Due to the long period of peace established by the Qing dynasty, a large number of candidates were able to make significant progress in their studies and apply for the exams. Their papers were all of similar quality so that examiners found it difficult to differentiate them and make their selections. Officials began to think of new ways to eliminate candidates rather than how to select the best scholars. A complicated set of formal requirements for the examinations was created which undermined the whole system.[75]

Failed candidates[]

Inevitably a large number of candidates failed the exams, often repeatedly. During the Tang period, the ratio of success to failure in the palace exam was 1:100 or 2:100. In the Song dynasty, the ratio of success to failure for the metropolitan exam was about 1:50. In the Ming and Qing dynasties, success to failure for the provincial exam was about 1:100. For every shengyuan in the country, only one in three thousand would ever become a jinshi. While most candidates were men of certain means, those from poor families risked everything on passing the exams. Ambitious and talented candidates who suffered repeated failures felt the bite of indignation, and failure escalated from disappointment to desperation, and sometimes even revolt.[76]

Huang Chao led a massive rebellion in the late Tang dynasty, after it had already been weakened by the An Lushan rebellion. He was born to a wealthy family in western Shandong. After repeated failures he created a secret society that engaged in illicit salt trading. Although Huang Chao's rebellion was ultimately defeated, it led to the final disintegration of the Tang dynasty. Among Huang Chao's cohort were other failed candidates such as Li Zhen, who targeted government officials, killed them and threw their bodies into the Yellow River.[49] of the Northern Song defected to Western Xia after failing the examinations. He aided the Tanguts in setting up a Chinese-style court. of the late Ming was a general in Li Zicheng's rebel army. Having failed to become a jinshi, he targeted high officials and members of the royal family, butchering them as retribution. Hong Xiuquan led the mid-19th-century Taiping Rebellion against the Qing dynasty. After his fourth and final attempt at the shengyuan exam, he had a nervous breakdown, during which he had visions of a heaven where he was part of a celestial family. Influenced by the teachings of Christian missionaries, Hong announced to his family and followers that his visions had been of God, his father, and Jesus Christ, his brother. He created the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom and waged war on the Qing dynasty, devastating parts of southeast China which would not recover for decades.[77]

Pu Songling (1640–1715) failed the examination multiple times. He immortalized the frustrations of candidates trapped in the relentless system in numerous stories that parodied the system.[78]

General discussion of late imperial system[]

Reformers charged that the set format of the "eight-legged essay" stifled original thought and satirists portrayed the rigidity of the system in novels such as Rulin waishi. In the twentieth century, the New Culture Movement portrayed the examination system as a cause for China's weakness in such stories as Lu Xun's Kong Yiji. Some have suggested that limiting the topics prescribed in examination system removed the incentives for Chinese intellectuals to learn mathematics or to conduct experimentation, perhaps contributing to the Great Divergence, in which China's scientific and economic development fell behind Europe.[79]

However, the political and ethical theories of Confucian classical curriculum have also been likened to the classical studies of humanism in European nations which proved instrumental in selecting an "all-rounded" top-level leadership.[80] British and French civil service examinations adopted in the late 19th century were also heavily based on Greco-Roman classical subjects and general cultural studies, as well as assessing personal physique and character. US leaders included "virtue" such as reputation and support for the US constitution as a criterion for government service. These features have been compared to similar aspects of the earlier Chinese model.[81] In the British civil service, just as it was in China, entrance to the civil service was usually based on a general education in ancient classics, which similarly gave bureaucrats greater prestige. The Cambridge-Oxford ideal of the civil service was identical to the Confucian ideal of a general education in world affairs through humanism.[82] Well into the 20th century, classics, literature, history and language remained heavily favoured in British civil service examinations.[83] In the period of 1925–1935, 67 percent of British civil service entrants consisted of such graduates.[84]

In late imperial China, the examination system was the primary mechanism by which the central government captured and held the loyalty of local-level elites. Their loyalty, in turn, ensured the integration of the Chinese state, and countered tendencies toward regional autonomy and the breakup of the centralized system. The examination system distributed its prizes according to provincial and prefectural quotas, which meant that imperial officials were recruited from the whole country, in numbers roughly proportional to each province's population. Elite individuals all over China, even in the disadvantaged peripheral regions, had a chance at succeeding in the examinations and achieving the rewards and emoluments office brought.[85]

The examination-based civil service thus promoted stability and social mobility. The Confucianism-based examinations meant that the local elites and ambitious would-be members of those elites across the whole of China were taught with similar values. Even though only a small fraction (about 5 percent) of those who attempted the examinations actually passed them and even fewer received titles, the hope of eventual success sustained their commitment. Those who failed to pass did not lose wealth or local social standing; as dedicated believers in Confucian orthodoxy, they served, without the benefit of state appointments, as civilian teachers, patrons of the arts, and managers of local projects, such as irrigation works, schools, or charitable foundations.[86]

Taking the exams[]

Candidates[]

During the Tang dynasty, candidates were either recommended by their schools or had to register for exams at their home prefecture. By the Song dynasty, theoretically all adult Chinese men were eligible for the examinations. The only requirement was education.[17]

In practice, a number of official and unofficial restrictions applied to who was able to take the imperial exams. The commoners were divided into four groups according to occupation: scholars, farmers, artisans, and merchants.[87] Beneath the common people were the so-called "mean" people such as boat-people, beggars, sex-workers, entertainers, slaves, and low-level government employees. Among the forms of discrimination faced by the "mean" people were restriction from government office and the credential to take the imperial exam.[88][89] Certain ethnic groups or castes such as the "degraded" Jin dynasty outcasts in Ningbo, around 3,000 people, were barred from taking the imperial exams as well.[90] Women were excluded from taking the exams. Butchers and sorcerers were also excluded at times.[91] Merchants were restricted from taking the exams until the Ming and Qing dynasties,[92] although as early as 955, the scholar-officials themselves were involved in trading activities.[93] During the Sui and Tang dynasties, artisans were also restricted from official service. During the Song dynasty, artisans and merchants were specifically excluded from the jinshi exam; and, in the Liao dynasty, physicians, diviners, butchers, and merchants were all prohibited from taking the examinations.[94] At times, quota systems were also used to restrict the number of candidates allowed to take or to pass the imperial civil service examinations, by region or by other criteria.

In one prefecture, within a few decades of the dynasty's founding, most of those who passed the jinshi examination came from families that had been members of the local elite for a generation or longer. Despite the six- or sevenfold increase in the numbers of men gaining jinshi, the sons of officials had better chances than most of getting these degrees...[95]

— Patricia Buckley Ebrey and Peter N. Gregory

Aside from official restrictions, there was also the economic problem faced by men of poorer means. The route to a jinshi degree was long and the competition fierce. Men who achieved a jinshi degree in their twenties were considered extremely fortunate. Someone who obtained a jinshi degree in their thirties was also considered on schedule. Both were expected to study continuously for years without interruption. Without the necessary financial support, studying for the exams would have been an impractical task. After completing their studies, candidates also had to pay for travel and lodging expenses, not to mention thank-you gifts for the examiners and tips for the staff. Banquets and entertainment also had to be paid for. As a result of these expenses, the nurturing of a candidate was a common burden for the whole family.[96]

Procedures[]

Each candidate arrived at an examination compound with only a few amenities: a water pitcher, a chamber pot, bedding, food (prepared by the examinee), an inkstone, ink and brushes. Guards verified a student's identity and searched him for hidden texts such as cheat sheets. The facilities provided for the examinee consisted of an isolated room or cell with a makeshift bed, desk, and bench. Each examinee was assigned to a cell according to their number. Paper was provided by the examiners and stamped with an official seal. The examinees of the Ming and Qing periods could take up to three days and two nights writing "eight-legged essays"—literary compositions with eight distinct sections. Interruptions and outside communication were forbidden for the duration of the exam. If a candidate died, officials wrapped his body in a straw mat and tossed it over the high walls that ringed the compound.[97]

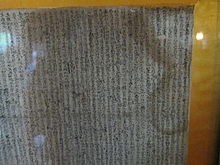

At the end of the examination, answer sheets were processed by the sealing office. The Ming era (ca. 1617) contains an entire section of stories about "Corruption in Education," most of which involve swindlers exploiting exam-takers' desperate attempts to bribe the examiner.[98] Exact quotes from the classics were required; misquoting even one character or writing it in the wrong form meant failure, so candidates went to great lengths to bring hidden copies of these texts with them, sometimes written on their underwear.[99] The Minneapolis Institute of Arts holds an example of a Qing dynasty cheatsheet, a handkerchief with 10,000 characters of Confucian classics in microscopically small handwriting.[100]

To prevent cheating, the sealing office erased any information about the candidate found on the paper and assigned a number to each candidate's papers. Persons in the copy office then recopied the entire text three times so that the examiners would not be able to identify the author. The first review was carried out by an examining official, and the papers were then handed over to a secondary examining official and to an examiner, either the chief examiner or one of several vice examiners. Judgments by the first and second examining official were checked again by a determining official, who fixed the final grade. Working with the team of examiners were a legion of gate supervisors, registrars, sealers, copyists and specialist assessors of literature.[17]

Pu Songling, a Qing dynasty satirist, described the "seven transformations of the candidate":

When he first enters the examination compound and walks along, panting under his heavy load of luggage, he is just like a beggar. Next, while undergoing the personal body search and being scolded by the clerks and shouted at by the soldiers, he is just like a prisoner. When he finally enters his cell and, along with the other candidates, stretches his neck to peer out, he is just like the larva of a bee. When the examination is finished at last and he leaves, his mind in a haze and his legs tottering, he is just like a sick bird that has been released from a cage. While he is wondering when the results will be announced and waiting to learn whether he passed or failed, so nervous that he is startled even by the rustling of the trees and the grass and is unable to sit or stand still, his restlessness is like that of a monkey on a leash. When at last the results are announced and he has definitely failed, he loses his vitality like one dead, rolls over on his side, and lies there without moving, like a poisoned fly. Then, when he pulls himself together and stands up, he is provoked by every sight and sound, gradually flings away everything within his reach, and complains of the illiteracy of the examiners. When he calms down at last, he finds everything in the room broken. At this time he is like a pigeon smashing its own precious eggs. These are the seven transformations of a candidate.[101]

— Pu Songling (1640-1715), who never passed the provincial examination

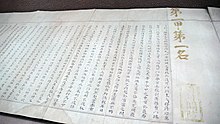

Ceremonies[]

In the main hall of the imperial palace during the Tang and Song dynasties there were two stone statues. One was of a dragon and the other of Ao (鳌), the mythical turtle whose chopped-off legs serve as pillars for the sky in Chinese legend. The statues were erected on stone plinths in the center of a flight of stairs where successful candidates (jinshi) in the palace examination lined up to await the reading of their rankings from a scroll known as the (金榜). When the list was published, all the names of the graduates were read aloud in the presence of the emperor, and recorded in the archival documents of the dynasty. Graduates were given a green gown, a tablet as a symbol of status, and boots. The first ranked scholar received the title of Zhuàngyuán (狀元/状元), and the honor of standing in front of the statue of Ao. This gave rise to the use of the phrases "to have stood at Ao's head" (占鳌头 [Zhàn ào tóu]), or "to have stood alone at Ao's head" (独占鳌头 [Dú zhàn ào tóu]) to describe a Zhuàngyuán, and more generally to refer to someone who excels in a certain field.[102]

Privileges[]

Shengyuan degree holders were given some general tax exemptions. Metropolitan exam graduates were allowed to buy themselves free of exile in cases of crime and to decrease the number of blows with the stick for a fee. Other than the title of jinshi, graduates of the palace examination were also exempted from all taxes and corvee labour.[17]

Post-examination appointments[]

The top three graduates of the palace examinations were directly appointed to the Hanlin Academy. Lower ranked graduates could be appointed to offices like Hanlin bachelor, secretaries, messengers in the Ministry of Rites, case reviewers, erudites, prefectural judges, prefects or county magistrates (zhixian 知縣).[103]

During the Tang dynasty, successful candidates reported to the Ministry of Personnel for placement examinations. Unassigned officials and honorary title holders were expected to take placement examinations at regular intervals. Non-assigned status could last a very long time especially when waiting for a substantive appointment. After being assigned to office, a junior official was given an annual merit rating. There was no specified term limit, but most junior officials served for at least three years or more in one post. Senior officials served indefinitely at the pleasure of the emperor.[104]

In the Song dynasty, successful candidates were appointed to office almost immediately and waiting periods between appointments were not long. Annual merit ratings were still taken but officials could request evaluation for reassignment. Officials who wished to escape harsh assignments often requested reassignment as a state supervisor of a Taoist temple or monastery. Senior officials in the capital also sometimes nominated themselves for the position of prefect in obscure prefectures.[105]

In addition to an obvious thinning of the numbers as one progresses into the upper ranks, the numbers also reveal important divisions between groups in the middle ranges of the administrative class. The distinct bulge in the court official group (grades twenty-five through twenty-three), with a total of 1,091 officials, the largest of any group, reveals the real promotion barrier between grades twenty-three and twenty-two. The wide disparity between directors (grades nineteen through fifteen) with a total of 160 officials and vice directors (grades twenty-two through twenty) with 619 officials also reveals the importance and the difficulty of promotion above grade twenty. These patterns formed because as early as 1066 the state effectively placed quotas on the number of officials who could be appointed to each group. Promotion across these major boundaries into the above group thus became more difficult.[106]

— Charles Hartman

Recruitment by examination during the Yuan dynasty constituted a very minor part of the Yuan administration. Hereditary Mongol nobility formed the elite nucleus of the government. Initially the Mongols drew administrators from their subjects. In 1261, Kublai Khan ordered the establishment of Mongolian schools to draw officials from. The School for the Sons of the State was established in 1271 to give two or three years of training for the sons of the Imperial Bodyguards so that they might become suitable for official recruitment.[107]

Recruitment by examination flourished after 1384 in the Ming dynasty. Provincial graduates were sometimes appointed to low-ranking offices or entered the Guozijian for further training, after which they might be considered for better appointments. Before appointment to office, metropolitan graduates were assigned to observe the functions of an office for up to one year. The maximum tenure for an office was nine years, but triennial evaluations were also taken, at which point an official could be reassigned. Magistrates of districts submitted monthly evaluation reports to their prefects and the prefects submitted annual evaluations to provincial authorities. Every third year, provincial authorities submitted evaluations to the central government, at which point an "outer evaluation" was conducted, requiring local administration to send representatives to attend a grand audience at the capital. Officials at the capital conducted an evaluation every six years. Capital officials of rank 4 and above were exempted from regular evaluations. Irregular evaluations were conducted by censorial officials.[108]

Graduates of the metropolitan examination during the Qing dynasty were assured influential posts in the officialdom. The Ministry of Personnel submitted a list of nominees to the emperor, who then decided all major appointments in the capital and in the provinces in consultation with the Grand Council. Appointments were generally on a three year basis with an evaluation at the end and the option for renewal. Officials rank three and above were personally evaluated by the emperor. Due to a population boom in the early modern era, qualified men far exceeded vacancies in the bureaucracy so that many waited for years between active duty assignments. Purchase of office became a common practice during the 19th century since it was very hard for qualified men to be appointed to one of the very limited number of posts.[109] Even receiving empty titles with no active assignment required a monetary contribution.[110]

Institutions[]

Ministry of Rites[]

The Ministry of Rites, under the Department of State Affairs, was responsible for organizing and carrying out the imperial examinations.[111]

Hanlin Academy[]

The Hanlin Academy was an institution created during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (r. 712-755). It was located directly in the palace compound and staffed by officials who drafted official documents such as edicts. These officials, commonly appointed from the top three ranks of the palace examination graduates, came to be known as academicians after 738, when a new building was constructed to provide them living quarters. The title "academician" was not only for the staff of the Hanlin Academy, but any special assignment to special posts. The number of academicians in the Hanlin Academy was fixed to six at a later date and they were given the task of doing paperwork and consulting the emperor. The Hanlin Academy drafted documents about the appointment and dismissal of high ministers, proclamation of amnesties, and imperial military commands. It also aided the emperor in reading documents.[112]

The number of Hanlin academicians was reduced to two during the Song dynasty. During the Yuan dynasty, a Hanlin Academy just for Mongols was created to translate documents. More emphasis was put on the oversight of imperial publications such as dynastic histories.[112]

In the Qing dynasty, the number of posts in the Hanlin Academy increased immensely and a Manchu official was installed at all times. The posts became purely honorary and the institution was reduced to just another stepping stone for persons seeking higher positions in the government. Lower officials in the Hanlin Academy often had other posts at the same time.[112]

Taixue[]

The Taixue (National University), was the highest educational institution in imperial China. During the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141-87 BC), Confucianism was adopted as the state doctrine. The Confucian scholar Dong Zhongshu suggested establishing a National University (Taixue) in the capital, Chang'an, so that erudites could teach the Classics. Teaching at the Taixue was a prestigious job because the emperor commonly picked from among them for appointment in high offices. At first the Taixue had only 50 students but increased to around 3,000 by the end of the millennium. Under the reign of Wang Mang (r. 9–23), two other educational institutions called the Biyong and Mingtang were established south of the city walls, each able to house 10,000 students. The professors and students were able to exercise some political power by criticizing their opponents such as governors and eunuchs. This eventually led to the arrest of more than 1,000 professors and students by the eunuchs.[113]

After the collapse of the Han dynasty, the Taixue was reduced to just 19 teaching positions and 1,000 students but climbed back to 7,000 students under the Jin dynasty (266–420). After the nine rank system was introduced, a "Directorate of Education" (Guozijian) was created for persons rank five and above, effectively making it the educational institution for nobles, while the Taixue was relegated to teaching commoners. Over the next two centuries, the Guozijian became the primary educational institute in the Southern Dynasties. The Sixteen Kingdoms and Northern Dynasties also created their own schools but they were only available for sons and relatives of high officials. The Northern Wei dynasty founded the Primary School of Four Gates.[113]

During the Sui dynasty, a Law School, Arithmetics School, and Calligraphy School were put under the administration of the Guozijian. These schools accepted the relatives of officials rank eight and below while the Taixue, Guozijian, and Four Gates School served higher ranks. By the start of the Tang dynasty (618-907), 300 students were enrolled in the Guozijian, 500 at the Taixue, 1,300 at the Four Gates School, 50 at the Law School, and a mere 30 at the Calligraphy and Arithmetics Schools. Emperor Gaozong of Tang (r. 649-683), founded a second Guozijian in Luoyang. The average age of admission was 14 to 19 but 18 to 25 for the Law School. Students of these institutions who applied for the state examinations had their names transmitted to the Ministry of Rites, which was also responsible for their appointment to a government post.[113]

During the Song dynasty, Emperor Renzong of Song founded a new Taixue at Kaifeng with 200 students enrolled. Emperor Shenzong of Song (r. 1067-1085) raised the number of students to 2,400. He also implemented the "three-colleges law" (sanshefa三舍法) in 1079, which divided the Taixue into three colleges. Under the three-colleges law, students first attended the Outer College, then the Inner College, and finally the Superior College. One of the aims of the three-colleges was to provide a more balanced education for students and to de-emphasize Confucian learning. Students were taught in only one of the Confucian classics, depending on the college, as well as arithmetics and medicine. Students of the Outer College who passed a public and institutional examination were allowed to enter the Inner College. At the Inner College there were two exams over a two-year period on which the students were graded. Those who achieved the superior grade on both exams were directly appointed to office equal to that of a metropolitan exam graduate. Those who achieved an excellent grade on one exam but slightly worse on the other could still be considered for promotion, and having a good grade in one exam but mediocre in another still awarded merit equal to that of a provincial exam graduate.[114]