Intercontinental Cup (football)

The trophy given to the winners | |

| Organising body | UEFA CONMEBOL |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1960 |

| Abolished | 2004 |

| Region | Europe South America |

| Number of teams | 2 |

| Related competitions | UEFA Champions League Copa Libertadores |

| International cup(s) | 13 |

| Last champions | (2nd title) |

| Most successful club(s) | (3 titles each) |

The Intercontinental Cup, rebranded as Toyota European/South American Cup from 1980 to 2004 after a sponsorship agreement with the automaker, was an international football competition endorsed by the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) and the Confederación Sudamericana de Fútbol (CONMEBOL),[1][2] contested between representative clubs from these confederations (representatives of most developed continents in the football world), usually the winners of the UEFA Champions League and the South American Copa Libertadores. It ran from 1960 to 2004, when it was succeeded by the FIFA Club World Cup, although they both ran concurrently in 1999–2000.

From its formation in 1960 to 1979, the competition was as a two-legged tie, with a playoff if necessary until 1968, and penalty kicks later. During the 1970s, European participation in the Intercontinental Cup became a running question due to controversial events in the 1969 final,[3] and some European Cup-winning teams withdrew.[4] From 1980, the competition was contested as a single match played in Japan and sponsored by multinational automaker Toyota, which offered a secondary trophy, the Toyota Cup.[5] At that point, the Japan Football Association was involved at logistic level as host,[6] though it continued to be endorsed by UEFA and CONMEBOL.[7][8]

The first winner of the cup was Spanish side Real Madrid, who beat Peñarol of Uruguay in 1960. The last winner was Portuguese side Porto, defeating Colombian side Once Caldas in a penalty shoot-out in 2004. The competition ended in 2004 and it merged with the FIFA Club World Cup in 2005.[9]

History[]

Beginnings[]

According to Brazilian newspaper Tribuna de Imprensa in 1958, the idea for the Intercontinental Cup rose in 1958 in a conversation between the then president of the Brazilian FA João Havelange and French journalist Jacques Goddet.[10] The first mention of the creation of the Intercontinental and Libertadores Cups was published by Brazilian and Spanish newspapers on 9 October 1958, referring to Havelange's announcement of the project to create such competitions, which he uttered during a UEFA meeting he attended as an invitee.[11][12][13][14] Prior to this announcement, the reigning European champions Real Madrid C.F. played just one intercontinental club competition, the 1957 Tournoi de Paris (they played also the 1956 Pequeña Copa, but they scheduled their participation in it before becoming European champions).[15] According to a French video record of the highlights of the 1957 Tournoi final match, between Real Madrid C.F. and CR Vasco da Gama, this was the first match ever dubbed as "the best team of Europe vs. the best team of South America", as Madrid was the European champions and Vasco was the "Brazilian" (in fact, Rio de Janeiro) champions,[16][17] having this match been held at Parc des Princes, then managed by the aforementioned Jacques Goddet, and for these reasons CR Vasco da Gama executives have claimed that the 1957 match and the 1958 FIFA World Cup Brazilian victory have influenced the Europeans on the importance of South American football, and thus the idea in 1958 for the creation of the Intercontinental Cup[18] (the Madrid team declined to participate in the 1958 Paris Tournoi for it was held just 5 days before the final of the 1957/1958 European Cup).[19] The Madrid-Vasco 1957 match was described as "being like a club world cup match" by the Brazilian press,[20][21] as was a June 1959 friendly between Real Madrid and Torneio Rio – S��o Paulo champions Santos FC, which Real Madrid won 5–3.[22]

Created in 1960 at the initiative of the European confederation (UEFA), with CONMEBOL's support, the European/South American Cup, known also as the Intercontinental Cup, was contested by the holders of the European Champion Clubs' Cup and the winners of its newly established South American equivalent, the Copa Libertadores. The competition was not endorsed by FIFA,[23] and in 1961 FIFA refused to allow it to take place unless the participants gave it a "private friendly match" status.[24] However, the competition went on regardless, with the endorsement of UEFA and CONMEBOL, both of whom include every edition of the competition in their records.[25][26][27] It was the brainchild of UEFA president Henri Delaunay, who also helped Jules Rimet in the realisation of the inaugural FIFA World Cup in 1930.[28][29] Initially played over two legs, with a third match if required in the early years (when goal difference did not count), the competition had a rather turbulent existence. The first winners of the competition were Spanish club Real Madrid. Real Madrid managed to hold Uruguayan side Peñarol 0–0 in Montevideo and trounce the South Americans 5–1 in Madrid to win.[30][31][32]

After the victory of Real Madrid in the first edition of the Intercontinental Cup, Barcelona newspaper El Mundo Deportivo hailed the Madrid team as the First World Champion Club, on the one hand pointing out that the competition "did not include Africans, Asians and other countries part to FIFA", on the other hand expressing doubt that these regions might present football of the same high quality of Europe and South America.[33] The Spaniards titled themselves world champions until FIFA stepped in and objected; citing that the competition did not include any other champions from the other confederations, FIFA stated that they can only claim to be intercontinental champions of a competition played between two organisations.[34] Peñarol would appear again the following year and come out victorious after beating Portuguese club Benfica on the playoff; after a 1–0 win by the Europeans in Lisboa and a 5–0 trashing by the South Americans, a playoff at the Estadio Centenario saw the home side squeeze a 2–1 win to become the first South American side to win the competition.[35][36][37]

In 1962 the tournament grew more in worldwide attention after it was swept through the sublime football of a Santos team led by Pelé, considered by some the best club team of all times.[38] Os Santásticos, also known as O Balé Branco (or white ballet), which dazzled the world during that time and containing stars such as Gilmar, Mauro, Mengálvio, Coutinho, and Pepe, won the title after defeating Benfica 3–2 in Rio de Janeiro and thrashing the Europeans 2–5 in their Estádio da Luz.[39][40][41] Santos would successfully defend the title in 1963 after being pushed all the way by Milan. After each side won 4–2 at their respective home legs, a playoff match at the Maracanã saw Santos keep the title after a tight 1–0 victory.[39][42] The competition attracted the interest of other continents. The North and Central America confederation, CONCACAF, was created, among other reasons, to attempt the participation of North-Central-American clubs in Copa Libertadores, and thus in the Intercontinental Cup.[41][43] Milan's fierce rivals, Internazionale, would go on to win the 1964 and 1965 editions, beating Argentine club Independiente on both occasions.[44][45][46][47][48] Peñarol gained revenge for their loss in 1960 by crushing Real Madrid 4–0 in aggregate in 1966.[37][49][50]

Rioplatense violence[]

However, as a result of the violence often practised in the Copa Libertadores by Argentine and Uruguayan clubs during the 1960s,[51] disagreements with CONMEBOL, the lack of financial incentives and the violent, brutal and controversial way the Brazilian national team was treated in the 1966 FIFA World Cup by European teams, Brazilian football—including its club sides—declined to participate in international competitions in the late 1960s, including the Copa Libertadores and consequently the Intercontinental Cup. During this time, the competition became dogged by foul play.[52] Calendar problems, acts of brutality, even on the pitch, and boycotts tarnished its image, to the point of bringing into question the wisdom of organising it at all.

The 1967 game between Argentina's Racing Club and Scotland's Celtic was a violent affair, with the third decisive game being dubbed "The Battle of Montevideo" after three players from the Scottish side and two from the Argentine side were sent off. A fourth Celtic player was also dismissed near the end of the game, but amid the chaos he got away with staying on.[53][54][55][56]

The following season, Argentine side Estudiantes de La Plata faced England's Manchester United in which the return leg saw Estudiantes come out on top of a bad-tempered series.[57][58][59] But it was the events of 1969 which damaged the competition's integrity.[60] After a 3–0 win at San Siro, Milan went to Buenos Aires to play Estudiantes at La Bombonera.[61][62][63] Estudiantes' players booted balls at the Milan team as they warmed up and hot coffee was poured on the Italians as they emerged from the tunnel by Estudiantes' fans. Estudiantes resorted to inflicting elbows and allegedly even needles at the Milanese team in order to intimidate them. Pierino Prati was knocked unconscious and continued for a further 20 minutes despite suffering from a mild concussion. Estudiantes goalkeeper Alberto Poletti also punched Gianni Rivera, but the most vicious treatment was reserved for Néstor Combin, an Argentinean-born striker, who had faced accusations of being a traitor as he was on the opposite side of the intercontinental match.[60][64][65]

Combin was kicked in the face by Poletti and later had his nose and cheekbone broken by the elbow of Ramón Aguirre Suárez. Bloodied and broken, Combin was asked to return to the pitch by the referee but fainted. While unconscious, Combin was arrested by Argentine police on a charge of draft dodging, having not undertaken military service in the country. The player was forced to spend a night in the cells, eventually being released after explaining he had fulfilled national service requirements as a French citizen.[60] Estudiantes won the game 2–1 but Milan took the title on aggregate.[60][63][64][65]

Italian newspaper Gazzetta dello Sport dubbed it "Ninety minutes of a man-hunt". The Argentinean press responded with "The English were right" – a reference to Alf Ramsey's famous description of the Argentina national football team as "animals" during the 1966 FIFA World Cup.[60][64][65] The Argentinean Football Association (AFA), under heavy international pressure, took stern action. Argentina's President, military dictator Juan Carlos Onganía, summoned Estudiantes delegate Oscar Ferrari and demanded "the severest appropriate measures in defence of the good name of the national sport. [It was a] lamentable spectacle which breached most norms of sporting ethics".[60][64][65] Poletti was banned from the sport for life, Suárez was banned for 30 games, and Eduardo Manera for 20 with the former and latter serving a month in jail.[60]

Degradation[]

Due to the brutality in the 1967 edition, FIFA was called into providing penalties and regulating the tournament. However, FIFA stated that it could not stipulate regulations in a competition that it did not organise. Though the competition was endorsed by UEFA and CONMEBOL, René Courte, FIFA's General Sub-Secretary, wrote an article shortly afterwards (1967) stating that FIFA viewed the competition as a "European-South American friendly match".[66] Courte's statement was endorsed by then–FIFA president Sir Stanley Rous, who then stated that FIFA saw the Intercontinental Cup as a friendly match.[67][68][69][70] After these controversial statements, Madrid newspaper ABC then pointed out that, though the Intercontinental Cup was not endorsed by FIFA, it was endorsed by UEFA and CONMEBOL, therefore being an "intercontinental jurisdiction" cup.[71] However, with the Asian and North-Central-American/Caribbean club competitions in place, FIFA opened the idea of supervising the Intercontinental Cup if it included those confederations, which was met with a negative response from its participating confederations, UEFA and CONMEBOL. According to Stanley Rous, CONCACAF and the Asian Football Confederation had requested, in 1967, their participation in the Intercontinental Cup, which was rejected by UEFA and CONMEBOL. In 1970, the FIFA Executive Committee gathering put forward, unsuccessfully, a proposal for the expansion of the Intercontinental Cup into a Club World Cup with representative clubs of every existing continental confederation.[72][73][74][75][76][77] Nevertheless, some European champions started to decline participation in the tournament after the events of 1969.[78]

Estudiantes would face Dutch side Feyenoord the following season, which saw the Europeans victorious. Oscar Malbernat ripped off Joop van Daele's glasses and trampled on them claiming that he was "not allowed to play with glasses".[79][80][81][82] Dutch side Ajax, European champions of 1971, would decline to face Uruguay's Nacional due to violence in previous editions, which resulted in European Cup runners-up, Greek side Panathinaikos, participating.[83][84][85] Ajax fears about Nacional's brutal game were confirmed. In the first game in Athens, Uruguayian striker Julio Morales broke the leg of Yiannis Tomaras with a brutal blow. According to the Greek press of the time, the sound of the fracture was heard up to the stands. The Greek defender collapsed on the ground and was transported unconscious out of the field. The medical diagnosis was a fracture of the tibia and fibula, an injury that effectively ended his career.[86] Nacional won the series 3–2 on aggregate.[83][84][85][87]

Ajax participated in 1972 against Independiente.[88][89][90] The team's arrival at Buenos Aires was extremely hostile: Johan Cruyff received several death threats from Independiente's local fan firms.[91] Due to the indifference from the Argentine police, Ajax manager Ştefan Kovács appointed an organised emergency security detail for the Nederlandse meester, headed by himself and team member Barry Hulshoff, described as a big and burly man.[91] In the first leg, Cruyff opened the scoring in Avellaneda at the 5th minute. As a result, Dante Mircoli retaliated with a vicious tackle a couple of minutes later; Cruyff was too injured to continue and the Dutch team found themselves being assaulted with tackles and punches.[88][89][90] Kovács had to convince his team to play on during half-time as his players wanted to withdraw.[88][89][90] Ajax squeezed a 1–1 tie and followed up with a 3–0 trounce in Amsterdam to win the Cup.[88][89][90][92] Although Ajax were the defending champions, they again declined to participate a year later after Independiente won the Libertadores again, leaving it to Juventus, European Cup runners-up, to play a single-match final won by the Argentines.[89][90][93][94]

Also in 1973, French newspaper L'Équipe, which helped to bring about the birth of the European Cup, volunteered to sponsor a Club World Cup contested by the champions of Europe, South America, Central and North America and Africa, the only continental club tournaments in existence at the time; the competition was to potentially take place in Paris between September and October 1974 with an eventual final to be held at the Parc des Princes.[78][95][96][97] The proposal, supported by the South Americans,[78] was dismissed due to the negativity of the Europeans.[97] In 1974, João Havelange was elected FIFA president, having made the proposal, among others, of creating a multicontinental Club World Cup. In 1975, L'Équipe once again made its 1973 proposal, again to no avail.

West German club Bayern Munich also declined to play in 1974 as Independiente again qualified to participate.[98][99][100][101] European Cup runners-up Atlético Madrid from Spain won the competition 2–1 on aggregate.[98][99] Once again, Independiente qualified to participate in 1975; this time, both finalists of the European Cup declined to participate and the competition was not played.[102] That same year, L'Équipe tried, once again, to create a Club World Cup, in which the participants would have been: the four semifinalists of the European Cup, both finalists of the Copa Libertadores, as well as the African and Asian champions. However, UEFA declined once again and the proposal failed.[103]

In 1976, when Brazilian side Cruzeiro won the Copa Libertadores, the European champions Bayern Munich willingly participated, with the Bavarians winning 2–0 on aggregate. In an interview with Jornal do Brasil, Bayern's manager Dettmar Cramer denied that Bayern's refusal to dispute the 1974 and 1975 Intercontinental Cups were a result of the rivals being Argentine teams. He claimed it was a scheduling impossibility, rather, which kept the Germans from participating. He also stated that the competition was not economically rewarding due to the team's fan base's disinterest in the Cup. To cover the costs of playing the first leg in Munich's Olympiastadion, the organizers needed to have a minimum of 25,000 spectators. However, due to heavy snow and cold weather, only 18,000 showed up. Because of this deficit, Cramer stated that if Bayern were to win the European Cup again, they would decline to participate as it held no assurances of income.[104]

Argentine side Boca Juniors qualified for the 1977 and 1978 editions, for which the European champions, English club Liverpool, declined to participate on both occasions. In 1977, Boca Juniors defeated European Cup runners-up, German club Borussia Mönchengladbach, 5–2 on aggregate.[105][106][107][108] Boca Juniors declined to face Belgian club Brugge in 1978 leaving that edition undisputed.[102] Paraguay's Olimpia won the 1979 edition against European Cup runners-up, Swedish side Malmö FF, after winning both legs.[109][110][111][112] However, the competition had greatly declined in prestige. After the 0–1 win of the South Americans in the first leg at Malmö, which saw fewer than 5,000 Swedish fans turn up, Spanish newspaper El Mundo Deportivo called the Cup "a dog without an owner".[78]

The truth is that the Intercontinental Cup is an adventitious competition without foundation.[clarification needed] It has no known owner, it depends on a strange consensus and the interested clubs are not tempted to risk much for so little money, as evidenced by the attendance at the game in Malmö, played, of course, in absence of this year's champion, Nottingham Forest, by the Swedish team, finalist in one of the most boring and worst games played to cap off the European Cup since 1956.

Spanish newspaper El Mundo Deportivo[78]

According to Brazilian newspaper O Estado de São Paulo, the deal for the establishment of the Interamerican Cup was made in 1968 by CONMEBOL and CONCACAF, and established that the Interamerican Cup champion club would be entitled to represent the American continent in the Intercontinental Cup.[113] According to the Mexican newspapers, after winning the 1977 and 1980 editions of the Interamerican Cup, Mexican clubs América and PUMAS Unam, and the Mexican Football Association, demanded, unsuccessfully, to participate in the Intercontinental Cup, either by representing the American continent against the European champions or by creating a UEFA-CONMEBOL-CONCACAF tournament.[114][115][116]

Rebirth in Japan[]

Seeing the deterioration of the Intercontinental Cup, Japanese motor corporation Toyota took the competition under its wing. It created contractual obligations to have the Intercontinental Cup played in Japan once a year in which every club participating were obliged to participate or face legal consequences. This modern format breathed new air into the competition which saw a new trophy handed out along with the Intercontinental Cup, the Toyota Cup.

In order to protect themselves against the possibility of European withdrawals, Toyota, UEFA and every European Cup participant signed annual contracts requiring the eventual winners of the European Cup to participate at the Intercontinental Cup—as a condition UEFA stipulated to the clubs' participation in the European Cup—or risk facing an international lawsuit from UEFA and Toyota.[117]

The first Toyota Cup was held in 1980 which saw Uruguay's Nacional triumph over Nottingham Forest. The 1980s saw a domination by South American sides as Brazil's Flamengo and Grêmio, Uruguay's Nacional and Peñarol, Argentina's Independiente and River Plate take the spoils once each after Nacional's victory in 1980. Only Juventus, Porto and Milan managed to bring the trophy to the European continent.

In that decade, the English Football Association tried organising a Club World Cup sponsored by promoting company West Nally only to be shot down by UEFA.[118]

The 1990s proved to be a decade dominated by European teams, as Milan, Red Star Belgrade, Ajax, Juventus, Real Madrid, Manchester United, and newcomers Borussia Dortmund of Germany were fuelled to victory by their economic powers and heavy poaching of South American stars. Only three titles went to South America, as São Paulo and Argentina's Vélez Sársfield came out the winners, each of them defeating Milan, with São Paulo's inaugural win being over Barcelona.

The 2000s would see Boca Juniors win the competition twice for South America, while European victories came from Bayern Munich, Real Madrid, and Porto. The 2004 Intercontinental Cup proved to be the last edition, as the competition was merged with the FIFA Club World Cup.

International participation[]

All the winning teams from Intercontinental Cup were regarded as de facto "world club champions".[119][120][121][122] According to some texts on FIFA.com, due to the superiority at sporting level of the European and South American clubs to the rest of the world, reflected earlier in the tournament for national teams, the winning clubs of the Intercontinental Cup were named world champions and can claim to be symbolic World champions,[123][124] in a "symbolic" club world championship,[125] while the FIFA Club World Cup would have another dimension,[126] as the "true" world club showdown,[127][128][129] created because, with the passage of time and the development of football outside Europe and South America, it had become "unrealistic" to continue to confer the symbolic title of world champion upon the winners of the Intercontinental Cup,[130] the idea to expand it being mentioned for the first time in 1967 by Stanley Rous as CONCACAF and the AFC had established their continental club competitions and requested the participation,[70][72][73][74][75][76][77] an expansion that was to occur only in 2000 through the 2000 FIFA Club World Championship. Nevertheless, some European champions started to decline participation in the tournament after the events of 1969.[78] Though "symbolic" or de facto as a club world championship,[27] the Intercontinental Cup has always been an official title at interconfederation level, with both UEFA and CONMEBOL having always considered all editions of the competition as part of their honours.[7][8]

FIFA recognition[]

Throughout the history of football, various attempts have been made to organise a tournament that identifies "the best club team in the world" – such as the Football World Championship, the Lipton Trophy, the Copa Rio, the Pequeña Copa del Mundo and the International Soccer League– due to FIFA's lack of interest or inability to organise club competitions,[131] – the Intercontinental Cup is considered by FIFA as the predecessor[132] to the FIFA Club World Cup, which was held for the first time in 2000.

On 27 October 2017, the FIFA Council, while not promoting statistical unification between the Intercontinental Cup and the Club World Cup, in respect to the history of the two tournaments[133] (which merged in 2005),[9] has made official (de jure) the world title of the Intercontinental Cup, recognising all the winners as club world champions,[134][135][136][137][138][139][140][141][142] with the same title of the FIFA Club World Cup winners, or "FIFA Club World Champions".[143][137][144][140][145][146][142][147][141]

FIFA recognises the Intercontinental Cup as the sole direct predecessor of the Club World Cup, and the champions of both aforementioned competitions are the only ones uncontroversially officially recognised by FIFA as Club World Champions, as seen in the FIFA Club World Cup Statistical Kit, the official document of FIFA's club competition.

Trophy[]

The competition trophy bears the words "Coupe Européenne-Sudamericaine" ("European-South American Cup") at the top. At the base of the trophy, there is the round logo of UEFA and a map of South America in a circle.

During the sponsorship by Toyota, the competition awarded an additional trophy, entitled "Toyota Cup", usually given to the winning team's vice-captain.

Cup format[]

From 1960 to 1979, the Intercontinental Cup was played in two legs. Between 1960 and 1968, the cup was decided on points only, the same format used by CONMEBOL to determine the winner of the Copa Libertadores final through 1987. Because of this format, a third match was needed when both teams were equal on points. Commonly this match was host by the continent where the last game of the series was played. From 1969 through 1979, the competition adopted the European standard method of aggregate score, with away goals.

Starting in 1980, the final became a single match. Up until 2001, the matches were held at Tokyo's National Stadium. Finals since 2002 were held at the Yokohama International Stadium, also the venue of the 2002 FIFA World Cup final.

Results[]

| Match was won during extra time | |

| Match was won on a penalty shoot-out | |

| ‡ | Play-off match where teams were tied on points (1 win and 1 defeat each) |

| # | European runner-up contested in place of European champion |

| Year | Country | Winners | Score | Runners-up | Country | Venue | Location | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | Real Madrid | 0–0 | Peñarol | Estadio Centenario | Montevideo, Uruguay | [148] | ||

| 5–1 | Santiago Bernabéu Stadium | Madrid, Spain | ||||||

| 1961 | Peñarol | 0–1 | Benfica | Estádio da Luz | Lisbon, Portugal | [149] | ||

| 5–0 | Estadio Centenario | Montevideo, Uruguay | ||||||

| 2–1‡ | Estadio Centenario | Montevideo, Uruguay | ||||||

| 1962 | Santos | 3–2 | Benfica | Estádio do Maracanã | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | [150] | ||

| 5–2 | Estádio da Luz | Lisbon, Portugal | ||||||

| 1963 | Santos | 2–4 | AC Milan | San Siro | Milan, Italy | [151] | ||

| 4–2 | Estádio do Maracanã | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | ||||||

| 1–0‡ | Estádio do Maracanã | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil | ||||||

| 1964 | Internazionale | 0–1 | Independiente | La Doble Visera | Avellaneda, Argentina | [152] | ||

| 2–0 | San Siro | Milan, Italy | ||||||

| 1–0 (a.e.t.)‡ | Santiago Bernabéu Stadium | Madrid, Spain | ||||||

| 1965 | Internazionale | 3–0 | Independiente | San Siro | Milan, Italy | [153] | ||

| 0–0 | La Doble Visera | Avellaneda, Argentina | ||||||

| 1966 | Peñarol | 2–0 | Real Madrid | Estadio Centenario | Montevideo, Uruguay | [154] | ||

| 2–0 | Santiago Bernabéu Stadium | Madrid, Spain | ||||||

| 1967 | Racing | 0–1 | Celtic | Hampden Park | Glasgow, Scotland | [155] | ||

| 2–1 | El Cilindro | Avellaneda, Argentina | ||||||

| 1–0‡ | Estadio Centenario | Montevideo, Uruguay | ||||||

| 1968 | Estudiantes | 1–0 | Manchester United | Estadio Boca Juniors | Buenos Aires, Argentina | [156] | ||

| 1–1 | Old Trafford | Manchester, England | ||||||

| 1969 | AC Milan | 3–0 | Estudiantes | San Siro | Milan, Italy | [157] | ||

| 1–2 | Estadio Boca Juniors | Buenos Aires, Argentina | ||||||

| 1970 | Feyenoord | 2–2 | Estudiantes | Estadio Boca Juniors | Buenos Aires, Argentina | [158] | ||

| 1–0 | De Kuip | Rotterdam, Netherlands | ||||||

| 1971 | Nacional | 1–1 | Panathinaikos#1[159] | Karaiskakis Stadium | Piraeus, Greece | [160] | ||

| 2–1 | Estadio Centenario | Montevideo, Uruguay | ||||||

| 1972 | Ajax | 1–1 | Independiente | La Doble Visera | Avellaneda, Argentina | [161] | ||

| 3–0 | Olympic Stadium | Amsterdam, Netherlands | ||||||

| 1973 | Independiente | 1–0 | Juventus#2[162] | Stadio Olimpico | Rome, Italy | [163] | ||

| 1974 | Atlético Madrid#3[164] | 0–1 | Independiente | La Doble Visera | Avellaneda, Argentina | [165] | ||

| 2–0 | Estadio Vicente Calderón | Madrid, Spain | ||||||

| 1975 | [166] | |||||||

| 1976 | Bayern Munich | 2–0 | Cruzeiro | Olympiastadion | Munich, West Germany | [167] | ||

| 0–0 | Mineirão | Belo Horizonte, Brazil | ||||||

| 1977 | Boca Juniors | 2–2 | Borussia Mönchengladbach#4[168] | Estadio Boca Juniors | Buenos Aires, Argentina | [169] | ||

| 3–0 | Wildparkstadion | Karlsruhe, West Germany | ||||||

| 1978 | [166] | |||||||

| 1979 | Olimpia | 1–0 | Malmö FF#5[170] | Malmö Stadion | Malmö, Sweden | [171] | ||

| 2–1 | Defensores del Chaco | Asunción, Paraguay | ||||||

| 1980 | Nacional | 1–0 | Nottingham Forest | National Stadium | Tokyo, Japan | [172] | ||

| 1981 | Flamengo | 3–0 | Liverpool | [173] | ||||

| 1982 | Peñarol | 2–0 | Aston Villa | [174] | ||||

| 1983 | Grêmio | 2–1 (a.e.t.) | Hamburger SV | [175] | ||||

| 1984 | Independiente | 1–0 | Liverpool | [176] | ||||

| 1985 | Juventus | 2–2 (a.e.t.) (4–2 p) | Argentinos Juniors | [177] | ||||

| 1986 | River Plate | 1–0 | Steaua București | [178] | ||||

| 1987 | Porto | 2–1 (a.e.t.) | Peñarol | [179] | ||||

| 1988 | Nacional | 2–2 (a.e.t.) (7–6 p) | PSV Eindhoven | [180] | ||||

| 1989 | AC Milan | 1–0 (a.e.t.) | Atlético Nacional | [181] | ||||

| 1990 | AC Milan | 3–0 | Olimpia | [182] | ||||

| 1991 | Red Star Belgrade | 3–0 | Colo-Colo | [183] | ||||

| 1992 | São Paulo | 2–1 | Barcelona | [184] | ||||

| 1993 | São Paulo | 3–2 | AC Milan#6[185] | [186] | ||||

| 1994 | Vélez Sársfield | 2–0 | AC Milan | [187] | ||||

| 1995 | Ajax | 0–0 (a.e.t.) (4–3 p) | Grêmio | [188] | ||||

| 1996 | Juventus | 1–0 | River Plate | [189] | ||||

| 1997 | Borussia Dortmund | 2–0 | Cruzeiro | [190] | ||||

| 1998 | Real Madrid | 2–1 | Vasco da Gama | [191] | ||||

| 1999 | Manchester United | 1–0 | Palmeiras | [192] | ||||

| 2000 | Boca Juniors | 2–1 | Real Madrid | [193] | ||||

| 2001 | Bayern Munich | 1–0 (a.e.t.) | Boca Juniors | [194] | ||||

| 2002 | Real Madrid | 2–0 | Olimpia | International Stadium | Yokohama, Japan | [195] | ||

| 2003 | Boca Juniors | 1–1 (a.e.t.) (3–1 p) | AC Milan | [196] | ||||

| 2004 | Porto | 0–0 (a.e.t.) (8–7 p) | Once Caldas | [197] | ||||

Notes[]

- After the events of the 1969 Intercontinental Cup, many European Cup Champions refused to play in the Intercontinental Cup.[198]

- #1 1970–71 European Cup finalists Panathinaikos (Greece) replaced the champions Ajax (Netherlands) who declined to participate.[160]

- #2 1972–73 European Cup finalists Juventus (Italy) replaced the champions Ajax (Netherlands) who declined to contest the meeting in South America, officially for financial reasons.[199][163]

- #3 1973–74 European Cup finalists Atlético Madrid (Spain) replaced the champions Bayern Munich (West Germany) who declined to participate.[165]

- #4 1976–77 European Cup finalists Borussia Mönchengladbach (West Germany) replaced the champions Liverpool (England) who declined to participate.[169]

- #5 1978–79 European Cup finalists Malmö FF (Sweden) replaced the champions Nottingham Forest (England) who declined to participate.[171]

- #6 1992–93 Champions League finalists AC Milan (Italy) replaced the champions Marseille (France) who were suspended due to a match fixing and bribery scandal.[186]

Performances[]

The performance of various clubs is shown in the following tables:[166][200]

Performance by club[]

| Club | Winners | Runners-up | Winning years | Runner-up years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 4 | 1969, 1989, 1990 | 1963, 1993, 1994, 2003 | |

| 3 | 2 | 1961, 1966, 1982 | 1960, 1987 | |

| 3 | 2 | 1960, 1998, 2002 | 1966, 2000 | |

| 3 | 1 | 1977, 2000, 2003 | 2001 | |

| 3 | — | 1971, 1980, 1988 | — | |

| 2 | 4 | 1973, 1984 | 1964, 1965, 1972, 1974 | |

| 2 | 1 | 1985, 1996 | 1973 | |

| 2 | — | 1962, 1963 | — | |

| 2 | — | 1964, 1965 | — | |

| 2 | — | 1992, 1993 | — | |

| 2 | — | 1972, 1995 | — | |

| 2 | — | 1976, 2001 | — | |

| 2 | — | 1987, 2004 | — | |

| 1 | 2 | 1968 | 1969, 1970 | |

| 1 | 2 | 1979 | 1990, 2002 | |

| 1 | 1 | 1983 | 1995 | |

| 1 | 1 | 1986 | 1996 | |

| 1 | 1 | 1999 | 1968 | |

| 1 | — | 1967 | — | |

| 1 | — | 1970 | — | |

| 1 | — | 1974 | — | |

| 1 | — | 1981 | — | |

| 1 | — | 1991 | — | |

| 1 | — | 1994 | — | |

| 1 | — | 1997 | — | |

| — | 2 | — | 1961, 1962 | |

| — | 2 | — | 1981, 1984 | |

| — | 2 | — | 1976, 1997 | |

| — | 1 | — | 1967 | |

| — | 1 | — | 1971 | |

| — | 1 | — | 1977 | |

| — | 1 | — | 1979 | |

| — | 1 | — | 1980 | |

| — | 1 | — | 1982 | |

| — | 1 | — | 1983 | |

| — | 1 | — | 1985 | |

| — | 1 | — | 1986 | |

| — | 1 | — | 1988 | |

| — | 1 | — | 1989 | |

| — | 1 | — | 1991 | |

| — | 1 | — | 1992 | |

| — | 1 | — | 1998 | |

| — | 1 | — | 1999 | |

| — | 1 | — | 2004 |

Performance by country[]

| Country | Winners | Runners-up | Winning clubs | Winning years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 | 9 | Boca Juniors, Independiente, Estudiantes, River Plate, Racing Club, Vélez Sarsfield | 1967, 1968, 1973, 1977, 1984, 1986, 1994, 2000, 2003 | |

| 7 | 5 | AC Milan, Juventus, Internazionale | 1964, 1965, 1969, 1985, 1989, 1990, 1996 | |

| 6 | 5 | Santos, São Paulo, Grêmio, Flamengo | 1962, 1963, 1981, 1983, 1992, 1993 | |

| 6 | 2 | Peñarol, Nacional | 1961, 1966, 1971, 1980, 1982, 1988 | |

| 4 | 3 | Real Madrid, Atlético Madrid | 1960, 1974, 1998, 2002 | |

| 3 | 2 | Bayern Munich, Borussia Dortmund | 1976, 1997, 2001 | |

| 3 | 1 | Ajax, Feyenoord | 1970, 1972, 1995 | |

| 2 | 2 | Porto | 1987, 2004 | |

| 1 | 5 | Manchester United | 1999 | |

| 1 | 2 | Olimpia | 1979 | |

| 1 | — | Red Star Belgrade | 1991 | |

| — | 2 | — | — | |

| — | 1 | — | — | |

| — | 1 | — | — | |

| — | 1 | — | — | |

| — | 1 | — | — | |

| — | 1 | — | — |

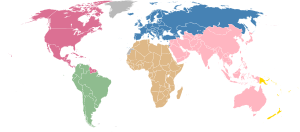

Performance by confederation[]

| Confederation | Winners | Runners-up | Winning clubs | Winning countries |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CONMEBOL | 22 | 21 | 13 | 4 |

| UEFA | 21 | 22 | 12 | 7 |

Notes[]

- After the events of the 1969 Intercontinental Cup, many European Cup champions refused to play in the Intercontinental Cup. On five occasions, they were replaced by the tournaments' runners-up. Additionally, two Intercontinental Cups were called off after runners-up, too, declined to participate.[201]

Coaches[]

- Carlos Bianchi won three editions as coach: one with

Vélez Sársfield in 1994, and two with

Vélez Sársfield in 1994, and two with  Boca Juniors in 2000 and 2003.

Boca Juniors in 2000 and 2003. - Luis Cubilla and Juan Mujica won cups both as players and coaches:

- Luis Cubilla (played for

Peñarol in 1961 and for

Peñarol in 1961 and for  Nacional in 1971, then coached

Nacional in 1971, then coached  Olimpia in 1979)

Olimpia in 1979) - Juan Mujica (played for

Nacional in 1971, and coached it in 1980)

Nacional in 1971, and coached it in 1980)

- Luis Cubilla (played for

Players[]

- Alessandro Costacurta and Paolo Maldini played five times in the competition, all with

AC Milan (1989, 1990, 1993, 1994, 2003).

AC Milan (1989, 1990, 1993, 1994, 2003).  Estudiantes (1968, 1969 and 1970) and

Estudiantes (1968, 1969 and 1970) and  Independiente (1972, 1973 and 1974) played in three consecutive years. A few players in those teams participated in all three, including Carlos Bilardo and Juan Ramón Verón.

Independiente (1972, 1973 and 1974) played in three consecutive years. A few players in those teams participated in all three, including Carlos Bilardo and Juan Ramón Verón.

All-time top scorers[]

- Pelé is the all-time top scorer in the competition having scored seven goals in three matches.

- Only six players scored at least three goals in the Intercontinental Cup.[206]

| Player | Club | Goals | Apps | Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 3 | 1962, 1963 | ||

| 6 | 6 | 1960, 1961, 1966 | ||

| 3 | 2 | 1971 | ||

| 3 | 3 | 1961 | ||

| 3 | 4 | 1961, 1962 | ||

| 3 | 4 | 1964, 1965 |

Hat-tricks[]

- Pelé is the only player in the history of the competition to have scored a hat-trick (Lisbon, 1962, second leg, against Benfica).

| Player | Nation | Club | Opponent | Goals | Goal times | Score | Tournament | Round | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pelé | 3 | 5–2 | 1962 Intercontinental Cup | Second leg | 11 October 1962 |

Man of the Match[]

The man of the match was selected since 1980. Here is the list of the winners.[207]

| Year | Player | Club |

|---|---|---|

| 1980 | ||

| 1981 | ||

| 1982 | ||

| 1983 | ||

| 1984 | ||

| 1985 | ||

| 1986 | ||

| 1987 | ||

| 1988 | ||

| 1989 | ||

| 1990 | ||

| 1991 | ||

| 1992 | ||

| 1993 | ||

| 1994 | ||

| 1995 | ||

| 1996 | ||

| 1997 | ||

| 1998 | ||

| 1999 | ||

| 2000 | ||

| 2001 | ||

| 2002 | ||

| 2003 | ||

| 2004 |

See also[]

- List of association football competitions

- List of world champion football clubs

References[]

- ^ "Legend – UEFA club competition" (PDF). Union des Associations Européennes de Football. 2009. p. 99. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ "Competencias oficiales de la CONMEBOL". Confederación Sudamericana de Fútbol (in Spanish). 2011. pp. 99, 107. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ^ "1969: Milan prevail in tough contest". Union des Associations Européennes de Football. 22 October 1969. Archived from the original on 26 December 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

- ^ Risolo, Don (2010). Soccer Stories: Anecdotes, Oddities, Lore, and Amazing Feats p.109. U of Nebraska Press. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Cup 2012 – Statistical Kit" (PDF). Fédération Internationale de Football Association. 6 November 2012. p. 9. Retrieved 21 November 2012.

- ^ Union of European Football Associations. "Rede do futebol mundial" (in Portuguese).

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Las competiciones oficiales de la CONMEBOL". CONMEBOL.

Official competitions are those recognized as valid by an organization and not only organized by it, in fact Conmebol includes in its list of official competitions the Club World Cup that is fully organized by FIFA.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Real Madrid CF". UEFA.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "FIFA Club World Championship TOYOTA Cup: Solidarity – the name of the game" (PDF). FIFA Activity Report 2005. Zurich: Fédération Internationale de Football Association: 60. April 2005 – May 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ Tribuna de Imprensa, ed. 2675, page. 8, of 23/10/1958. In Portuguese.

- ^ "Edición del $dateTool.format('EEEE d MMMM yyyy', $document.date), Página $document.page - Hemeroteca". hemeroteca.mundodeportivo.com.

- ^ "ABC (Madrid) – 09/10/1958, p. 58 – ABC.es Hemeroteca". ABC. Spain.

- ^ "Jornal do Brasil – Pesquisa de arquivos de notícias Google". Google News.

- ^ "O Estado de S. Paulo – Acervo Estadão".

- ^ "Real Madrid, la leyenda blanca". leyendablanca.galeon.com.

- ^ The 1957 match was held amidst a CR Vasco da Gama's European trip, in which the Brazilian club, then reigning Rio de Janeiro champions (1956 league), was often presented to the European audience as being the Brazilian champion, since then there existed neither a national championship in Brazil, nor the Torneio Rio – São Paulo had been played in 1956.

- ^ "CR Vasco da Gama's supporters' site "Casaca": "Há 55 anos o Vasco conquistava o I Torneio de Paris"".

- ^ "Dario lembra vitória do Vasco sobre Real, em 1957: 'Não há clube igual'".

- ^ Brazilian newspaper Folha da Manhã, 21/may/1958, pag. 13.

- ^ Jornal dos Sports, Rio de Janeiro newspaper, ed. 8526, 18 June 1957, page 8, on Vasco da Gama's victory over Real Madrid at the 1957 Tournoi de Paris.

- ^ Tribuna da Imprensa, Rio de Janeiro newspaper, 14 June 1957, ed. 2264, on the Vasco da Gama Vs. Real Madrid CF match for the 1957 Tournoi de Paris, citing Real Madrid as current European Champions and Vasco da Gama as the current Rio de Janeiro champions.

- ^ "Ultima Hora (RJ) – 1951 a 1984 – DocReader Web". memoria.bn.br.

- ^ "UEFA Direct, nº 105, 2011, page 15. Access on 04/Feb/2013" (PDF).

- ^ "Edición del Saturday 3 June 1961, Página 2 - Hemeroteca". hemeroteca.mundodeportivo.com.

- ^ uefa.com. "Real Madrid – UEFA". UEFA.

- ^ Carluccio, Jose (2 September 2007). "¿Qué es la Copa Libertadores de América?" [What is the Copa Libertadore de América?] (in Spanish). Historia y Fútbol. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Goodbye Toyota Cup, hello FIFA Club World Championship". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "World Club Cup deserves respect". BBC. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "World Club Cup deserves respect". British Broadcasting Corporation Brasil (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cup 1960". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cup 1960". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Trofeos de Fútbol". Real Madrid Club de Fútbol (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 3 October 2009. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Edición del Monday 5 September 1960, Página 3 - Hemeroteca". hemeroteca.mundodeportivo.com.

- ^ "La Copa Intercontinental, un perro sin amo". El Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cup 1960". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cup 1961". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Palmarés: Resumen de títulos oficiales del Club Atlético Peñarol". Club Atlético Peñarol (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Cunha, Odir (2003). Time dos Sonhos [Dream Teams] (in Portuguese). ISBN 85-7594-020-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Intercontinental Cups 1962 and 1963". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cup 1962". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Títulos". Santos Futebol Clube (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cup 1963". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "European Commissioner visits UEFA" (PDF). Union Européenne de Football Association. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cups 1964 and 1965". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. Archived from the original on 12 February 2009. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cup 1964". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cup 1965". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Palmares: PRIMA COPPA INTERCONTINENTALE – 1964". Football Club Internazionale Milano S.p.A (in Italian). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Palmares: SECONDA COPPA INTERCONTINENTALE – 1965". Football Club Internazionale Milano S.p.A (in Italian). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cups 1966". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cup 1966". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "História da Libertadores". Campeones do Futebol (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "European-South American Cup". Union Européenne de Football Association. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cup 1967". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1967". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Copa Intercontinental 1967". Racing Club de Avellaneda (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "The Battle of Montevideo: Celtic Under Siege". Waterstones. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cup 1968". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1968". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Titulos". Club Estudiantes de La Plata (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 23 April 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Estudiantes leave their mark". Entertainment and Sports Programming Network Football Club. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cup 1969". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. Archived from the original on 24 January 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1969". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Coppa Intercontinentale 1969". Associazione Calcio Milan (in Italian). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Coppa Intercontinentale 1969: Estudiantes-Milan, sfida selvaggia". Storie di Calcio (in Italian). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Partidos inolvidables: Estudiantes – Milan (Final Intercontinental 1969/1970)". Fútbol Primera (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "La FIFA rehuye el bulto" [FIFA shuns the bulge] (PDF). El Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). 25 November 1967. p. 8. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Edición del Friday 3 November 1967, Página 6 - Hemeroteca". hemeroteca.mundodeportivo.com.

- ^ "The Glasgow Herald – Pesquisa de arquivos de notícias Google". Google News.

- ^ "La Stampa – Consultazione Archivio". archiviolastampa.it.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "ABC Madrid 03-11-1967". abc.es. 12 August 2019. p. 97. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ "ABC (Madrid) – 08/11/1967, p. 87 – ABC.es Hemeroteca". ABC. Spain.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "La Copa Intercontinental de futbol debe ser oficial". El Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "La FIFA rehuye el bulto". El Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "La FIFA, no controla la Intercontinental". El Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "El proyecto de Copa del Mundo se discutira en Méjico". El Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "¿Nueva Copa Intercontinental?". El Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "La Copa del Mundo Inter-clubs se amplia". El Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Europa ha desvalorizado la Copa Intercontinental". El Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cup 1970". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. Archived from the original on 9 December 2008. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cup 1970". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "1970: Feyenoord unfazed by Estudiantes". Union des Associations Européennes de Football. 2 March 1980. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ "Feyenoord viert veertigjarig jubileum winst Wereldbeker" (in Dutch). Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Archived from the original on 11 September 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Intercontinental Cup 1971". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. Archived from the original on 25 June 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Intercontinental Cup 1971". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Copa Intercontinental 1971". Club Nacional de Football (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Όταν ο Παναθηναϊκός έγινε... παγκόσμιος (pics & video)!". agones.gr (in Greek). Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ "1971: Artime puts paid to Panathinaikos". Union Européenne de Football Association. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Intercontinental Cup 1972". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. Archived from the original on 22 June 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Intercontinental Cup 1972". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Erelijst". Amsterdamsche Football Club Ajax (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 15 November 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Super Cup was the last trophy Ajax..." Football Journey. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "1972: Cruyff comes good for Ajax". Union des Associations Européennes de Football. 2 March 1980. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cup 1973". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. Archived from the original on 6 March 2008. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "1973: Independiente resist Juve challenge". Union des Associations Européennes de Football. 2 March 1980. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ "European Cup: 50 Years" (PDF). Union Européenne de Football Association. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Una ide para los cinco campeones de cada continente". El Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Una copa mundial de clubs con los campeones de Europa, África, Sudamérica y América Central". El Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Intercontinental Cup 1974". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. Archived from the original on 4 December 2009. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Intercontinental Cup 1974". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Sala de Trofeos". Club Atlético de Madrid, S.A.D. (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "1974: Aragonés brings joy to Atlético". Union des Associations Européennes de Football. 2 March 1980. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Intercontinental Cup". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Una idea para los cinco campeones de cada continente". El Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Taça não interessa mais aos alemães (page 20)". Jornal do Brasil (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cup 1977". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. Archived from the original on 30 May 2009. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cup 1977". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "El Club: Titulos". Club Atlético Boca Juniors (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 8 June 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "1977: Boca Juniors brush aside Mönchengladbach". Union des Associations Européennes de Football. 2 March 1980. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cup 1979". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cup 1979". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "1979: Club Olimpia overpower Malmö". Union des Associations Européennes de Football. 2 March 1980. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ "Intercontinental Cup 1979". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ Brazilian newspaper O Estado de São Paulo, 10/10/1968, page.28

- ^ Mexican neswspaper El Informador, 14 and 16 April 1978, referring to Club America's claim to participate in the Intercontinental Cup. Archived 6 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mexican newspaper El Siglo de Torréon. Archive. "Los Pumas Por La Copa Concacaf-EUFA" (15/May/1981, page 13).

- ^ Mexican newspaper El Siglo de Torréon. Archive. "Mediocridad existente en el futbol del area de Concacaf." (29/August/1980, page 11).

- ^ Aguilar, Francesc (18 September 1992). "La negociación será difícil" [Negotiations will be difficult] (PDF). El Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). p. 8. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "La Copa Intercontinental el 11-D en Tokio: No habra una Copa Mundial de Clubes". El Mundo Deportivo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Championship TOYOTA Cup: Solidarity – the name of the game" (PDF). FIFA Activity Report 2005. Zurich: Fédération Internationale de Football Association: 60. April 2005 – May 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ "Goodbye Toyota Cup, hello FIFA Club World Championship". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. 10 December 2004. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 24 December 2010.

- ^ "Ten tips on the planet's top club tournament". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. 28 July 2005. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2009.

- ^ "We are the champions". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. 1 December 2005. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2009.

- ^ "We are the Champions". FIFA. December 2005. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

[...] clubs that have been named world champions [...]

- ^ "Ten things you never knew". FIFA. December 2005. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

Among this year's six representatives, Brazil's Sao Paulo are the only team that can claim to have been world champions.

- ^ "Goodbye Toyota Cup, hello FIFA Club World Championship". FIFA. 10 December 2004. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

With the passage of time, it became apparent that it was unrealistic to continue to confer the symbolic title of "Club World Champion" on the basis of a single match between the European and South American champions.

- ^ "Goodbye Toyota Cup, hello FIFA Club World Championship". FIFA. 10 December 2004. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

As of 2005, the Toyota Cup, traditionally a one-off match between the champions of Europe and South America, will take on a whole new dimension when it becomes the FIFA Club World Championship, disputed by the champion clubs from all six continents.

- ^ "Japan welcomes the world with open arms". FIFA. 28 July 2005. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

Brought up watching the annual Europe-South America clash, Japanese fans are counting the days to the kick off of the true world club showdown.

- ^ "Goodbye Toyota Cup, hello FIFA Club World Championship". FIFA. 10 December 2004. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

According to the new format, which enters into force in 2005, once again in Japan, the respective winners of the six "champions cups" of each confederation will qualify for the FIFA Club World Championship. «I am convinced that this is the best formula for everyone», argues Michel Platini, a FIFA Executive Committee member and former Toyota Cup winner from 1985. «It won't make the clubs' trips any longer, but by playing an extra game, the club crowned this time will be true world champions» continued the former Juventus playmaker.

- ^ "Continental champions prepare for Tokyo draw". FIFA. 28 July 2005. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

Initially a one-off contest between the champions of South America and Europe, the Toyota Cup, which superseded the Intercontinental Cup in 1980, has been revamped by FIFA to reach out to all confederations and associations across the globe so the winners may truly be regarded as the best club side in the world.

- ^ Goodbye Toyota Cup, hello FIFA Club World Championship, FIFA.com. Accessed on 10 December 2004. Accessed on 08/03/2015: With the passage of time, it became apparent that it was unrealistic to continue to confer the symbolic title of "club world champion" on the basis of a single match between the European and South American champions.

- ^ "50 years of the European Cup" (PDF). Union des Associations Européennes de Football. October 2004. pp. 7–9. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Championship TOYOTA Cup: Solidarity – the name of the game" (PDF). FIFA Activity Report 2005. Zurich: Fédération Internationale de Football Association: 62. April 2005 – May 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Cup UAE 2017: Statistical Kit FIFA" (PDF). pp. 15, 40, 41, 42.

- ^ “While it does not promote the statistical unification of tournaments, that is, has not absorbed to the Intercontinental Cup (merged with FIFA Club World Cup in 2005), FIFA is the only organization with worldwide jurisdiction over continental confederations and, then, the only one that can confer a title on that level, ergo the title assigned by FIFA (with Official Documents issued after the Council decision) to the winners of the Intercontinental Cup is legally a FIFA world title." cfr. "FIFA Statutes, April 2016 edition" (PDF). p. 19. cfr.

- ^ For FIFA statute, official competitions are those for representative teams organized by FIFA or any confederation. Representative teams are usually national teams but also club teams that represent a confederation in the interconfederal competitions or a member association in a continental competition cfr. "FIFA Statutes, April 2016 edition" (PDF). p. 5. cfr. "FIFA Club World Cup UAE 2018: Statistical-kit" (PDF). 10 December 2018. p. 13. cfr. "2018/19 UEFA Champions League regulations" (PDF). p. 10.

- ^ FIFA in its statute recognizes as official all competitions organized by itself and by the continental confederations; indeed, on its website, it calls the competitions played under its auspices simply "FIFA Tournaments". cfr. FIFA (April 2016). "FIFA Statutes, April 2016 edition" (PDF). p. 5. cfr. FIFA.COM. "Fifa tournaments".

- ^ Jump up to: a b "FIFA Council approves key organisational elements of the FIFA World Cup™" Check

|url=value (help). origin1904-p.cxm.fifa.comfifa-council-approves-key-organisational-elements-of-the-fifa-world-cu-2917722. Retrieved 7 July 2021. - ^ "FIFA acepta propuesta de CONMEBOL de reconocer títulos de copa intercontinental como mundiales de clubes" (in Spanish). conmebol.com. 29 October 2017.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Cup UAE 2018: Statistical-kit" (PDF). 10 December 2018. p. 13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Campo, Carlo. "FIFA recognises all winners of Intercontinental Cup as club world champions". theScore.com. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "FIFA declares Man United '99 world champs". ESPN.com. 27 October 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "La FIFA reconoció a los ganadores de la Intercontinental como campeones mundiales". Goal.com (in Spanish).

- ^ “While it does not promote the statistical unification of tournaments, that is, has not absorbed to the Intercontinental Cup (merged with FIFA Club World Cup in 2005), the title was conferred from the world federation (with Official Documents issued after the Council decision) so it is legally a FIFA world title" cfr. "FIFA Club World Cup Qatar 2019™" (PDF). p. 12. cfr.

- ^ "FIFA Club World Cup UAE 2018: Statistical-kit" (PDF). 10 December 2018. p. 13.

- ^ "Real Madrid! Sixth Club World Cup!". Realmadrid.com.

- ^ "Historical decision, register Club World Cup is rewritten". Foxsports.it (in Italian).

- ^ "Pelé Just Won A Club World Championship". The18. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1960".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1961".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1962".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1963".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1964".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1965".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1966".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1967".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1968".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1969".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1970".

- ^ Panathinaikos played in place of Ajax

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Intercontinental Club Cup 1971".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1972".

- ^ Juventus played in place of Ajax

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Intercontinental Club Cup 1973".

- ^ Atlético Madrid played in place of Bayern Munich

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Intercontinental Club Cup 1974".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Intercontinental Club Cup".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1976".

- ^ Borussia Mönchengladbach played in place of Liverpool

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Intercontinental Club Cup 1977".

- ^ Malmö FF played in place of Nottingham Forest

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Intercontinental Club Cup 1979".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1980".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1981".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1982".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1983".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1984".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1985".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1986".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1987".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1988".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1989".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1990".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1991".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1992".

- ^ AC Milan played in place of Marseille

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Intercontinental Club Cup 1993".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1994".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1995".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1996".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1997".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1998".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 1999".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 2000".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 2001".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 2002".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 2003".

- ^ "Intercontinental Club Cup 2004".

- ^ "THE DECLINE, FALL AND REBIRTH OF THE INTERCONTINENTAL CUP".

- ^ "Intercontinental Cup 1973". Fédération Internationale de Football Association. Archived from the original on 6 March 2008. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ "Hall of Honour".

- ^ "THE DECLINE, FALL AND REBIRTH OF THE INTERCONTINENTAL CUP".

- ^ http://www.rsssf.com/tablesi/intconclub62.html

- ^ http://www.rsssf.com/tablesi/intconclub63.html

- ^ "Extraordinary Pele crowns Santos in Lisbon". FIFA. 11 October 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ^ "King-less Santos retain throne in style". FIFA. 16 November 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ^ "Trivia on Intercontinental (Toyota) Cup".

- ^ "Toyota Cup – Most Valuable Player of the Match Award". Archived from the original on 24 December 2008.

Bibliography[]

- Amorim, Luís (1 December 2005). Intercontinental Cup 1960-2004. LuísAmorimEditions. ISBN 978-989-95672-5-2.

- Amorim, Luís (1 September 2005). Taça Intercontinental 1960-2004. Multinova. ISBN 989-551-040-3.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Intercontinental Cup (association football). |

- Intercontinental Cup (football)

- Defunct CONMEBOL club competitions

- Defunct UEFA club competitions

- World championships in association football

- Recurring sporting events established in 1960

- Recurring events disestablished in 2004

- November sporting events

- December sporting events