Jane Ingham

Jane Ingham | |

|---|---|

Ingham (right) at Cambridge in 1966 | |

| Born | Rose Marie Tupper‑Carey 15 August 1897 Leeds, England |

| Died | 10 September 1982 (aged 85) Cambridge, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | University of Leeds (1928: MSc) |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions |

|

| Academic advisors | Joseph Hubert Priestley |

Rose Marie "Jane" Ingham (née Tupper‑Carey /tˈʌpə ˈkɛəri/; 15 August 1897 – 10 September 1982), was an English botanist and scientific translator. She was the third daughter of Helen Mary Tupper‑Carey, née Chapman, and Canon Albert Darrell. She was educated at Claire House School, an all girl school in Lowestoft, England, and the University of Leeds. In 1919, she studied general zoology at the Citadel Hill Laboratory of the Marine Biological Association in Plymouth. In the following year, she was appointed a research assistant to Joseph Hubert Priestley in the Botany Department at the University of Leeds.

Ingham and Priestley, were the first to isolate cell walls from meristematic tissues in Vicia faba (broad beans). They fractionated the isolated walls, analysed the fractions and concluded that the meristematic cells had walls containing protein. She also studied the cork cambium in trees and water absorption at the endodermis in the growing points of plant roots. In 1930, she joined the Imperial Bureau of Plant and Crop Genetics, at the School of Agriculture in Cambridge, England, as a scientific officer and translator. The bureau was responsible for publishing a series of abstract journals on various aspects of crop breeding and genetics. After her marriage to Albert Ingham, she worked from home on a part-time basis, and in 1939, was put in charge of the bureau after her deputy director, Penrhyn Stanley Hudson, fell ill.

In the 1920s, Ingham was appointed a sub-warden of Weetwood Hall, the hall of residence for women students at the University of Leeds. She was appointed the first honorary secretary of the Leeds branch of the British-Italian League, whose aim was to found a chair in Italian at the University of Leeds. She joined the university amateur dramatics society, and around 1922, she sat for a portrait by William Roberts. She spent the war years in Princeton, New Jersey, with her two sons, unable to return to England after travelling there just before the outbreak of World War II.

Life[]

Early life[]

Rose Marie was born on 15 August 1897, at Cromer House, Cromer Terrace, Leeds, the third daughter of Helen Mary Tupper‑Carey (1864–1938), née Chapman, and Canon Emeritus Albert Darrell (1866–1943).[2] She was baptised at Donhead St Andrew, Wiltshire, on 14 September 1897.[3] Helen Mary, was the eldest daughter of Reverend Horace Edward Chapman, a former rector of Donhead St Andrew, and Adelaide Maria, née Fletcher.[4][a] They married at Donhead St Andrew on 16 May 1890.[6]

Tupper‑Carey's father was Chaplain to the King from 1938, and formerly chaplain at Monte Carlo. He was the son of the Reverend Tupper Carey and Helen Jane, née Sandeman, and educated at Eton and Christ Church, Oxford, where he graduated with Second Class Honours in Modern History in 1888, and in the following year, obtained a Second Class in Theology. After training at Cuddesdon Theological College he was ordained in 1890 and became curate of Leeds, where he remained until 1898. That year he was appointed head of Christ Church Mission, Poplar, and in 1901, he was appointed rector of St Margaret's Church, Lowestoft.[b] In 1910 he left to become canon residentiary of York, and in 1917 moved to Huddersfield, where he was vicar until 1924.[9]

Education[]

Tupper‑Carey was educated at Claire House School, an all girl school in North Parade, Lowestoft, that specialised in the teaching of the French language and culture.[10][11][12] She was taught French by Marie Noémie Camille Maury and demonstrated an early aptitude for the language. In 1908, she won a preliminary degree in French, in examinations organised by the National Society of French Professors in England, that included candidates from other girls' schools in England.[11] The examinations were held annually in February, June and November, and the society granted certificates of aptitude for French taught in England, the written tests consisting of translation and composition (prose and poetry), essay, and questions on 17th to 19th century French literature.[13]

Leeds and postgraduate life[]

In 1916, Tupper‑Carey entered the University of Leeds to study botany.[14] Her paternal grandmother, Helen Jane Carey, née Sandeman, was a keen amateur botanist and specimen collector;[15] a popular and fashionable pastime in Victorian England,[16]: 29 and in her youth, Tupper‑Carey would collect wild flowers for local parish shows.[17] Her elder sister, Edith, known as "Betty" to her friends and family,[18] had married the author Michael Sadleir in 1914. Sadleir was the only son of Sir Michael Ernest Sadler, the then Vice‑chancellor of the University of Leeds.[19] In 1919, Tupper‑Carey was given desk space at the Citadel Hill Laboratory of the Marine Biological Association, Plymouth, to study general zoology.[20] In the following year, she was appointed a research assistant to Joseph Hubert Priestley in the Botany Department at the University of Leeds.[21][c]

Around 1922, Tupper‑Carey sat for a portrait by William Roberts, the "English Cubist" artist, the painting being titled "Portrait of Miss Jane Tupper‑Carey", and later, "Head of a Woman", after Roberts was unable to remember the name of the sitter.[23] It was shown for the first time in November 1923 at New Chenil Galleries, Chelsea, with The Times commenting on the exhibition:[24][25]

Properly to appreciate his powers the visitor should look first at such things as the "Portrait of Miss Tupper‑Carey" ... not because they are the best things in the exhibition, but because they make evident the fact that the treatment of form in some of the other works is deliberate, for the double purpose of racy comment and articulate design.

— Art Exhibitions. Mr. William Roberts, The Times 9 November 1923, p. 17

St John Hutchinson KC, a barrister, art collector, and trustee of the Tate, presented the portrait to the Contemporary Arts Society (CAS) in 1924, and CAS gifted it to the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, Swansea in 1928.[26][23] The commissioning of the portrait, and whether Tupper‑Carey knew William Roberts, or his wife, Sarah, née Kramer, an immigrant to Leeds, is uncertain.[d] Barry Plummer, art historian for the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, has stated that it was a commission, and furthermore, Roberts would supplement his income by taking on various portrait commissions.[24]

Tupper‑Carey's father had been a former Honorary Secretary of the Oxford University Dramatic Society and she herself had a continuing interest in the arts and amateur dramatics.[29] She had performed as Philaminte in her school's 1908 production of three scenes from Molière's Les Femmes Savantes,[12][e] and in the 1920s, joined the university amateur dramatics society, acting in several well-received roles, such as Sybil Bumont in the The Watched Pot.[30] On 6 December 1928, she took part in a fashion show of dresses through the ages, at the Albion Hall, Leeds, in aid of St Faith's Homes. She wore a high‑waisted, skin-tight coat of red cloth edged with fur, a long blue skirt trimmed with six rows of black velvet, and a feather toque on top of her head. Her appearance was greeted with "shrieks of laughter" from the audience.[31]

By 1926, Tupper‑Carey had been appointed sub-warden at Weetwood Hall, the university hall of residence for women students, with her close friend, Annie Redman King, as warden.[32][f] Weetwood Hall had opened as a hall of residence in 1920, and had been expanded in 1920s to accommodate up to 60 female students.[34] In the same year, she was appointed the first honorary secretary of the Leeds branch of the British-Italian League. The League's aims were to found a chair in Italian at the University of Leeds and foster relations between the two countries. The inaugural meeting of the branch was held on 6 December 1926, in the university refectory, with Professor Piero Rébora as guest speaker, the then recently appointed Professor of Italian Studies at the University of Manchester.[35]

Cambridge and marriage[]

In January 1930, Tupper‑Carey moved to 3 Brooklands Avenue, Cambridge, to commence work at the Imperial Bureau of Plant and Crop Genetics.[36] After six months, Albert Ingham followed her to Cambridge, after he had been appointed a fellow and director of studies at King's College, following the sudden death of Frank Ramsey.[37]: 271–272 [14] She had met him after he had been appointed reader in mathematical analysis at the University of Leeds in 1926.[32][g] They announced their engagement in May 1932; they had been engaged for some time but had not wished to make it public until lectures were over. However, their engagement came as a surprise to their circle of friends in Leeds, as there had not been the slightest suggestion that they were romantically involved.[38][14]

They married at St Edward's Church, Cambridge in the morning of 6 July 1932. Her father had travelled from Monte Carlo, where he was chaplain, to marry them, accompanied by her mother. They wanted a quiet wedding: Her parents, brother-in-law, Michael Sadleir, who gave her away, sister, Edith ("Betty") Sadleir, and her friend Annie Redman King, being the only people present. They left immediately after the ceremony to catch the boat train to Europe, honeymooning in Italy, before returning to Cambridge on 8 August 1932.[39] They moved to 14 Millington Road, Cambridge, and lived there for the rest of their lives, interrupted only by World War II.[14][37]: 272 [h]

The war years[]

They were ideally complementary, Jane as quick in thought and action as 'A. E.' was deliberate.

John Charles Burkill, Dictionary of National Biography (1981)

In July 1939, Albert Ingham had been awarded a Leverhulme Research Fellowship to study at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS), in Princeton, New Jersey.[42][43][44] By now, they had two sons, Michael Frank and Stephen Darrell,[i] and the entire family sailed from Liverpool on 1 September 1939, arriving in New York on 13 September 1939.[45] The sailing gave them enough time to reach Princeton for the start of the first term at IAS on 1 October 1939. While they were at sea, and only two days into their voyage, Britain declared war on Germany.

The Inghams were hesitant to bring their family back due to reports from Europe containing speculation of imminent total war.[46] The IAS had provided them with a house at 291 Nassau Street, Princeton, and consequently, they made the decision to keep the family there rather than return home.[43] Albert Ingham left Princeton at the end of the first term on 16 December 1939.[47][48] Alan Pars recommended him for an Admiralty job in America, knowing that she and the children were still there.[49][j] In 1942, she and the children had moved to 293 Nassau Street, Princeton, the neighbouring house to 291 Nassau Street.[51] She had become friends with Lyn Irvine, after Irvine and her two sons were evacuated to America in 1940, and this friendship would continue after the war.[52][53]: 48

Later life and death[]

The Ingham's owned a punt, called Pete, moored in the River Cam, and it was used regularly during the summer for trips and picnics.[40]: 127 They also went on many trips abroad, including India, and walking holidays in the French Alps.[54]: 563 [40]: 15, 128 It was on such a holiday that Albert Ingham died of a heart attack on a high path near Haute-Savoie, south-eastern France.[55][56] After his death she resisted offers for her husband's mathematical notes and papers, instead keeping the papers in a cupboard at the house.[40]: 46

[She] was very wiry and fit ... [I have] an abiding memory of how fast and vigorously my grandmother would walk. She was always frustrated with my brother and I as we 'dawdled' fifty yards behind her. We just could not keep up with her furious pace.

— Dr Mark Ingham describing Jane Ingham, in Afterimages: Photographs as an External Autobiographical Memory System (2005), p. 46

Jane Ingham died at Cambridge on 10 September 1982 and was cremated at the Cambridge City Crematorium, Huntingdon Road, Dry Drayton, on 20 September 1982.[57][58] Alan Pars, Ingham's friend, and former colleague of her husband at Cambridge, sent a wreath.[59][60] Her ashes were scattered in Hayley Wood, close to where her husband's remains had been scattered in 1967.[56]

Career[]

University of Leeds Botany Department[]

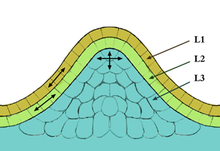

In 1920, Tupper‑Carey was appointed a research assistant to Joseph Hubert Priestley in the Botany Department at the University of Leeds.[21] She first investigated the endodermis at the growing points of plant roots and its role in water absorption.[21] This first physiological study was followed in 1923 to 1924 by two New Phytologist papers. Tupper‑Carey and Priestley were the first to isolate cell walls from meristematic tissues in Vicia faba (broad beans).[22]: 4 They fractionated the isolated walls, analysed the fractions for protein, cellulose, and pectin, and concluded that the meristematic cells had walls containing protein.[61] They also studied the differences in shoot and root development, and the role of the cork cambium in plants.[22]: 4 Described as a "brilliant scholar",[14] she was awarded a MSc degree on 3 July 1928, for her thesis "Geotropism or Gravity and Growth", at a degree ceremony held in Leeds Town Hall.[62][63]

Tupper-Carey was a skilled microscopist, and when Reginald Dawson Preston, the biophysicist, joined the Botany Department in July 1929, she taught him how to cut and stain sections.[64][65]: 350 She would use panchromatic plates, with colour screens, to photograph sections of cortical cells in etiolated broad beans, stained with Nile blue sulphate in glycerine.[66][k] She also provided unpublished work to William Pearsall on the swelling in buffer solutions of air-dry, but living, embryos of broad bean seeds.[68]

Composition of the cell wall at the apical meristem[]

Tupper‑Carey and Priestley, in Tupper‑Carey & Priestley (1923), were the first to isolate cell walls from the middle lamella of the radicle and plumule meristems of Vicia faba.[22]: 4 [69]: 191 They fractionated the isolated walls and analysed the fractions for protein, cellulose, and pectin. They noted that the cellulose walls of the radicle failed to react with iodine and sulphuric acid, or with chloriodide of zinc.[l] They showed that the cellulose in the wall of the radicle is masked by other substances, particularly proteins and fatty acids. In the plumule, the cellulose is associated with greater quantities of pectin, but less protein and fatty acid, particularly when the adult parenchyma is growing in light.[71][72] They concluded that the meristematic cells had walls containing a protein‑pectin complex,[61][69]: 191 [70]: 78 that is, these walls "... commencing as interfaces in a protein-containing medium may be regarded as composed at first mainly of protein".[73]

Frederic Wood, in Wood (1926), questioned their results, and concluded that less than 0.001% of protein was found in the cell walls of the plants examined. Tripp, Moore & Rollins (1951), Dieckert & Snowden (1960), and King & Bayley (1963), found protein in the cells but were unable to rule out the possibility of cytoplasmic contamination.[61] It is now known that the middle lamella consists of a pectic polysaccharide rich material. However, the material properties and molecular organisation of the middle lamella are still not fully understood.[74]

Nutation curvature of the arch in the hypocotyl[]

In Tupper‑Carey (1928b), Tupper‑Carey found that in the arch of the hypocotyl from sunflower seeds, Helianthus annuus, there are considerably more cells on the outside than on the inside. The nutation curvature of the hypocotyl was investigated and the number of cells in 10 layers of cortex (outside and inside) in the curve was determined using microtome sectioning. Counting from the beginning to the end of the curvature, the result was "3,299 cells on the upper side as against 1,531 on the lower".[75]

This result means that the convex side of the arch leads the concave side, not only in terms of cell extension, but also in cell division behaviour i.e. a different division rate would cause the growth difference. Consequently, the concave and convex sides show profound physiological differences.[75] The observation that in the hypocotyl the cells on the convex side are considerably larger than those on the inside could be explained by the uneven transverse transport of the growth hormone auxin. Auxin has a strengthening effect on the elongation growth of the cells. In the case of nutation phenomena, it is possible that curvature only occurs in a narrowly limited section of the shoot.[76]: 2

Kaldewey (1957) measured the differences in the length of the sub-epidermal cells on the outer and inner periphery of the arch in the nutation curvature of the pedicels of snake's head fritillary, Fritillaria meleagris. The result was expected if the curvature is based exclusively on differences in elongation growth. A difference in width or thickness between the sub-epidermal cells of the outer and inner periphery of the arch of curvature was not found. Salisbury (1916) found good agreement between the ratio of the epidermal cell lengths and the arch lengths of the nutation curvature of the epicotyl in seedlings of different woody plants. The findings of Tupper‑Carey, Salisbury, and Kaldewey, do not necessarily contradict each other as the epidermis and sub-epidermal layer may well behave differently than cortical layers in terms of division and extension growth.[75]

Vascular cambial tissue reorganisation[]

In Tupper‑Carey (1930), Tupper‑Carey ring-barked laburnum and sycamore trees, but left bridges of tissue with horizontal portions linking the bark above and below the cut, that is, a zigzag bridge of phloem was left across the ring.[77][78] At first the lack of pressure within these bridges resulted in the formation of callus-like tissue, and the cambial initials, by repeated division, come to resemble ray cells. At a later stage, some of this mass of isodiametric (roughly spherical) cells became elongated horizontally in the direction of the bridge tissue.[79] Xylem and phloem is eventually formed in the horizontal portion of the bridge with its tracheary elements extended in a horizontal direction.[77]

It has been postulated that calluses are formed because the cambium cells cannot function correctly under a change of orientation. For example, the altered direction of sap flow might affect the direction of cambial cell growth. Pressure, nutrient movements, and cambial basipetal auxin transport have also been suggested as causes.[78]

Imperial Bureau of Plant and Crop Genetics[]

In February 1930, Tupper‑Carey joined the Imperial Bureau of Plant and Crop Genetics as a translator and scientific officer. The bureau was housed in a few rooms at the Plant Breeding Institute, in the School of Agriculture, Downing Street, Cambridge.[80]: 140 The Imperial Agricultural Bureaux were set-up in 1929 under the control of an executive council, and were located at British universities and research institutes, under the directorship of the heads of those research stations.[81][m] They were responsible for publishing a series of abstract jopurnals on eight branches of agricultural science and were financed out of a common fund to which all the British Empire countries represented on the Executive Council contributed a share.[83][84][n]

Professor Sir Rowland Biffen was the first director of the Cambridge bureau, and Tupper‑Carey's supervisor, Penrhyn Stanley Hudson ("Pen") OBE, was deputy director.[80]: 140 Hudson was a remarkable linguist, who spoke most European languages fluently, including Russian and Ukrainian.[83][o] Biffen's research had been in wheat varieties and he was an early proponent of using genetics to improve crop plants.[85] It was realised from the beginning that the bureau could inform people working overseas of recent scientific developments, many of whom had no ready access to scientific literature, especially those in foreign languages.[80]: 139

Tupper‑Carey was fluent in French, Italian, German and Swedish, and as a whole, the bureau was capable of dealing with Spanish, Dutch, and Russian.[80]: 139 [14] To make sure nothing was overlooked, it was decided to make periodic visits to the London libraries to consult periodicals not available in Cambridge. This was a large undertaking and it was decided to deal with certain crops in succession.[80]: 139 A start was made with wheat, by examining the literature, typing out the titles on index cards measuring 13 by 8 centimetres (5 by 3 inches), and cross-indexing according to author and Dewey number.[83]

From this material, a bibliography was compiled dealing with the various aspects of wheat breeding and genetics, with some of the foreign language papers requiring complete translations, and others, detailed summaries.[80]: 139 [86] Similar bibliographies were compiled on barley breeding, breeding varieties resistant to disease, lodging in cereals, oat breeding, rice breeding, and interspecific crosses.[80]: 141 These classified abstracts were published in a quarterly journal called Plant Breeding Abstracts and included book reviews, notices of new journals, and articles in associated fields such as applied statistics and other sciences.[87] To formalise the translation and cataloguing process, Tupper‑Carey attended the eighth conference of the Association of Special Libraries and Information Bureaux (ASLIB), at Oxford, in September 1931, as a member of the panel of expert translators.[88][89] After her marriage, Ingham worked from home on a part-time basis, translating most of the German documents,[90][83] and in 1939, was put in charge of the bureau after Hudson fell ill.[91]

Names[]

Ingham's father, Albert Darell, changed his surname by deed poll from Carey to Tupper‑Carey on 3 November 1887.[92][93] Ingham was known as "Marie" at her first school, Clare House, Lowestoft.[11] A number of sources call her by the name "Jane", including the title of her portrait by William Roberts,[23] engagement announcement,[14] death notice in The Times,[57] and her husband's Royal Society memoir,[37]: 272 and in most instances, note she was born Rose Marie. Her academic work was authored as "R. M. Tupper‑Carey".[94] She is not listed in the International Plant Names Index (IPNI) but was recorded as "Tupper‑Carey, R. M." in the 1931 edition of the International Address Book of Botanists.

Publications[]

As author[]

- Priestley, Joseph Hubert; — (1922). "Physiological Studies in Plant Anatomy IV. The Water Relations of the Plant Growing Point". New Phytologist. London: Wiley-Blackwell. 21 (4): 210–229. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1922.tb07598.x. ISSN 0028-646X. JSTOR 2428025. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- —; Priestley, Joseph Hubert (2 July 1923). "The composition of the cell-wall at the apical meristem of stem and root". Proceedings of the Royal Society. Series B, Containing Papers of a Biological Character. London: Royal Society. 95 (665): 109–131. Bibcode:1923RSPSB..95..109T. doi:10.1098/rspb.1923.0026. ISSN 0950-1193. JSTOR 80874.

Communicated by Dr Frederick Blackman, FRS. Received 25 April 1923.

Refereed by William Lawrence Balls in May 1923.[95] - —; Priestley, Joseph Hubert (1924). "The Cell Wall in the Radicle of Vicia faba and the Shape of the Meristematic Cells". New Phytologist. London: Wiley-Blackwell. 23 (3): 156–159. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1924.tb06630.x. ISSN 0028-646X. JSTOR 2427781. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- — (1928). Geotropism or Gravity and Growth (MSc). Leeds: University of Leeds. pp. 1–86. OCLC 1184171098. 30106005063069. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

Tupper‑Carey's MSc thesis.

- — (1928). "The Development of the Hypocotyl of Helianthus annuus considered in connection with its Geotropic Curvatures". Proceedings of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society. Science Section Part 2. 1925 to 1929 Parts 5 to 10. Leeds: Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society. 1: 361–368. ISSN 0024-0281. OCLC 848524378.

Communicated by Professor Joseph Hubert Priestley. Received 4 December 1928.

- — (1930). "Observations on the anatomical changes in tissue bridges across rings through the phloem of trees". Proceedings of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society. Science Section Part 2. December 1929 to May 1934. Leeds: Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society. 2: 86–94. ISSN 0024-0281. OCLC 848524378.

Communicated by Professor Joseph Hubert Priestley. Received 26 February 1930.

As experimental collaborator[]

- Pearsall, William Harold; Ewing, James (1 March 1927). "The Absorption of Water by Plant Tissue in Relation to External Hydrogen-Ion Concentration" (PDF). The Journal of Experimental Biology. London. 4 (3): 245–257. ISSN 0022-0949. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

Tupper‑Carey provided unpublished work on the swelling in buffer solutions of the air-dry, but living, embryos of broad bean seeds.

- Priestley, Joseph Hubert (31 July 1926). "Light and Growth II. On the Anatomy of Etiolated Plants". New Phytologist. London: Wiley-Blackwell. 25 (3): 145–170. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1926.tb06688.x. ISSN 0028-646X. JSTOR 2427687. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Priestley, Joseph Hubert; Swingle, Charles Fletcher (December 1929). Vegetative Propagation from the Standpoint of Plant Anatomy. Technical Bulletin 115. Washington: United States Department of Agriculture. pp. 1–98. OCLC 254290053. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- Rhodes, Edgar; Woodman, Rowland Marcus (1925). "The Fatty Substances of the Plant Growing Point". Proceedings of the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society. 1925 to 1929. Leeds: Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society. 1: 27–36. ISSN 0024-0281. OCLC 848524378.

Communicated by Professor Joseph Hubert Priestley. Received 21 October 1925.

See also[]

Footnotes[]

- ^ Chapman was a son of banker David Barclay Chapman, who in 1875, purchased the advowson of St Andrew Donhead, and presented Horace Edward as the rector.[5]

- ^ For a photograph of Albert Darell Tupper‑Carey, taken circa 1910, see the photograph taken by Harry Jenkins in Lowestoft History (1910).[7] Albert Darell is seated front and second to the right in the photograph.[8]

- ^ Priestley had accepted the Chair of Botany at Leeds University in 1911, in succession to Professor Vernon Herbert Blackman.[22]: 3

- ^ Kramer's brother went to Leeds School of Art, and with the help of Michael Sadler and others, entered the Slade School of Fine Art with fellow student William Roberts.[27] Michael Sadler owned works by Roberts, and like his son, Michael Sadleir, was a keen collector of art, and purchased works by other young English artists such as Stanley Spencer and Mark Gertler.[28]

- ^ Her father was in the audience to see her performance, and after the play had finished, he addressed the audience in French.[12]

- ^ Annie Redman King, née Peniston, a fellow Leeds graduate, was warden from 1919 to 1948. King had gained her First Class Bachelor of Science Honours degree in Botany in 1913 and became an assistant lecturer and demonstrator in the Zoology Department at the University of Leeds.[33]

- ^ Albert Ingham, whose hobby was mountaineering, flew from a holiday in Central Europe for the interview in Leeds.[14]

- ^ The house was called Millington Road by family and visitors. The gas lamp outside Millington Road is listed by Historic England.[40]: 14 [41]

- ^ In 1961, Michael was elected a Fellow of King's College, Cambridge, and later joined the staff of the University Observatory at Oxford.[37]: 273

- ^ Pars was godfather to their sons.[50]

- ^ Nile blue sulphate, or Nile red, is obtained by boiling a solution of Nile blue with sulphuric acid.[67]

- ^ Cells that have cellulose in their walls are stained blue by chloriodide of zinc, or a solution of iodine followed by sulphuric acid.[70]: 77

- ^ On 1 January 1948, the Executive Council of the Imperial Agricultural Bureaux changed the name of the Bureaux to the Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux.[82]

- ^ The other bureaux were:[81]

- Soil science at Rothamsted Research

- animal nutrition at the Rowett Institute, Aberdeen

- animal health at the Veterinary Laboratories Agency, Weybridge

- animal genetics at the University of Edinburgh

- animal helminthology at St Albans

- herbage plant genetics at Aberystwyth

- fruit production at the East Malling Research Station.

- ^ Hudson's idea of a summer holiday was "to go to some distant place on a foreign freighter, practising the language, whatever it might be, with the crew".[83]

References[]

- ^ Leeds Library and Information Service (2010). "Cromer Terrace, numbers 5 and 7 (Cromer House)". Leodis. Leeds: Leeds City Council. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ "Births". The Times (35285). London. 18 August 1897. p. 1. ISSN 0140-0460. Gale CS17228050. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ "Baptisms at Donhead St Andrew. 1858 to 1922" (1897) [Baptism register]. Parish Records of Donhead St Andrew, Series: Registers, ID: 1732/5, p. 77. Chippenham: Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^

Eton College (1908). The Eton Register. 1883 to 1889. Part 5. Eton: Old Etonian Association. Spottiswoode. p. 8. OCLC 946484245. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

1883, 5th Form.

- ^ Harding, Timothy David (2015). Joseph Henry Blackburne: A Chess Biography. Jefferson: McFarland & Company. p. 330. ISBN 978-0-7864-7473-8. OCLC 900306725. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ "Donhead St. Andrew. Marriage of Miss Helen Mary Chapman and the Rev. A. D. Tupper Carey". Western Gazette. Yeovil. 19 September 1890. p. 8. OCLC 14708041. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Taylor, Arthur (1910). "Reverend Albert Darell Tupper‑Carey, Rector of St Margaret's, Lowestoft, 1901 to 1910. Seated front and second from the right. Photograph includes 8 other clergy". LowestoftHistory. Harry Jenkins (1866–1952). Lowestoft. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Jenkins, Harry. "Rector of St Margaret's Lowestoft 1901 to 1910. Photograph includes 8 other clergy" (1910) [Photograph]. Lowestoft people, Series: Canon Tupper Carey, ID: 1300/72/35/112/2. Lowestoft: Suffolk Record Office. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ "Obituary. Canon A. D. Carey". The Times (49657). London. 22 September 1943. p. 8. ISSN 0140-0460. Gale CS135740726. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ "In the French competition". Lowestoft Journal. Lowestoft. 17 November 1900. p. 5. OCLC 900349662. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Scholastic Successes". Lowestoft Journal. Lowestoft. 25 July 1908. p. 5. OCLC 900349662. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Claire House School". Lowestoft Journal. Lowestoft. 5 December 1908. p. 5. OCLC 900349662. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The Teaching of French". Boston Guardian. Boston. 7 March 1908. p. 5. OCLC 556439943. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Mather, Joyce (2 June 1932). "A Yorkshire Woman's Notes. A Later Development". Leeds Mercury. Leeds. p. 8. OCLC 1016307518. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "An Important Discovery - Helen J. Tupper Carey, Ebbesborne Wake, Salisbury". Leeds Mercury. Leeds. 13 August 1883. p. 8. OCLC 1016307518. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Shteir, Ann B. (1997). "Gender and 'Modern' Botany in Victorian England". Osiris. Women, Gender, and Science: New Directions. Chicago: History of Science Society. 12: 29–38. doi:10.1086/649265. ISSN 0369-7827. JSTOR 301897. PMID 11619778. S2CID 42561484.

- ^ "Wild Flower Show at Lowestoft". Lowestoft Journal. Lowestoft. 4 July 1908. p. 5. OCLC 900349662. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Noted Author's Home in the Cotswolds". Tatler. London. 19 April 1944. p. 81. ISSN 0263-7162. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The Wedding of Mr. M. T. Sadler and Miss Edith Tupper Carey". The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. Leeds. 4 June 1914. p. 8. ISSN 0963-1496. OCLC 18793101. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Report of the Council. Occupation of Tables" (PDF). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. New series. Plymouth: Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 12 (2): 369. July 1920. ISSN 0025-3154. OCLC 1167043554. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Sixteenth Report. 1919 to 1920. Botany" (PDF). Annual Report. Leeds: University of Leeds: 78. 1926. OCLC 877673406. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Scott, Lorna Iris (June 1946). "Joseph Hubert Priestley, D.S.O., B.Sc., F.L.S., 1883 to 1944". New Phytologist. London: Wiley-Blackwell. 45 (1): 3–4. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1946.tb05040.x. ISSN 1469-8137. JSTOR 2428931. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Cleall, David; Davenport, Bob (2019). "William Roberts. Portrait of Miss Jane Tupper‑Carey". English Cubist. Tenby. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Plummer, Barry (2020). "William Roberts (1895-1980). Head of a Woman, Miss Jane Tupper‑Carey, 1924". Glynn Vivian Art Gallery. Swansea. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ "Art Exhibitions. Mr. Willam Roberts". The Times (43494). London. 9 November 1923. p. 17. ISSN 0140-0460. Gale CS285939049. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ "Obituary. Mr. St. John Hutchinson, K.C. Recorder of Hastings". The Times (49376). London. 26 October 1942. p. 6. ISSN 0140-0460. Gale CS102841178. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Parkin, Michael (5 December 1992). "Obituary: Sarah Roberts". The Independent. London. ISSN 0951-9467. OCLC 185201487. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^

Piper, John (1944). Catalogue of an exhibition of selected paintings, drawings and sculpture from the collection of the late Sir Michael Sadler. London: Leicester Galleries. OCLC 80686873.

Ernest Brown & Phillips Ltd., January to February 1944.

- ^ Mackinnon, Alan Murray (1910). "7 Lent Term 1885". The Oxford Amateurs. A short history of theatricals at the university. With a foreword by Reverend James Adderley. London: Chapman & Hall. p. 115. OCLC 976537471. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ "Leeds University Amateurs". The Stage. London. 5 December 1929. p. 26. ISSN 0038-9099. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Mather, Joyce (7 December 1928). "Fashions Through the Ages. A Leeds Parade. Nothing New in Dresses To-day". Leeds Mercury. Leeds. p. 3. OCLC 1016307518. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Jump up to: a b

"Twenty-Second Report. 1925 to 1926" (PDF). Annual Report. Leeds: University of Leeds: 40, 57. 1926. OCLC 877673406. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

Pages 209 and 226 in the PDF.

- ^ King, Annie Redman. "King, Annie Redman 1911 to 1948" (1932) [Boxes]. Personalia, ID: LUA/PER/045. Leeds: University of Leeds. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Leeds Library and Information Service (2010). "Weetwood Hall". Leodis. Leeds: Leeds City Council. 2004317_55933780. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ "Letter to the Editor. The British-Italian League in Leeds". Leeds Mercury. Leeds. 20 November 1926. p. 4. OCLC 1016307518. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Diels, Ludwig; Merrill, Elmer Drew; Chipp, Thomas Ford; et al., eds. (1931). International Address Book of Botanists. Bentham Trustees. London: Baillière, Tindall & Cox. p. 204. OCLC 877383380. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Burkill, John Charles (1 November 1968). "Albert Edward Ingham, 1900 to 1967". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. Cambridge: Royal Society. 14: 271–286. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1968.0012. ISSN 0080-4606. JSTOR 769447.

- ^ "Marriages". The Times (46146). London. 30 May 1932. p. 15. ISSN 0140-0460. Gale CS252651198. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Mather, Joyce (3 August 1932). "The Tupper‑Carey Wedding". Leeds Mercury. Leeds. p. 6. OCLC 1016307518. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Ingham, Mark (1 June 2005). Afterimages: Photographs as an External Autobiographical Memory System and a Contemporary Art Practice (PhD). Goldsmiths, University of London, Visual Arts Department [Fine Art]. London. OCLC 1006191005. 7465. Archived from the original on 21 August 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2021 – via PhilPapers.

- ^ Historic England. "Gas Lamp Outside Nos 12 and 14, Millington Road (1394519)". National Heritage List for England. London. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ "Leverhulme Fellowships". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. 13 July 1939. p. 6. ISSN 0307-5850. OCLC 624981792. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Jump up to: a b 1939 to 1940 Second Term (PDF). Faculty and Staff Directory (Report). IAS Publications Collection. Princeton: Institute for Advanced Study. 1939. p. 3. hdl:20.500.12111/5963. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Bulletin No. 9 (PDF) (Report). IAS Publications Collection. Princeton: Institute for Advanced Study. April 1940. p. 12. hdl:20.500.12111/5956. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ "S. S. Vandyck. Departed Liverpool 1 September 1939" (13 September 1939) [JPEG]. Book Indexes for New York Passenger Lists, Series: 1 January 1906 to 1 April 1942, ID: T715 157914759, p. 183. Washington: National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Pars, Leopold Alexander. "Letter from A.E. Ingham at Berkeley, California" (1930) [Letter]. Papers of Leopold Alexander Pars, Series: Correspondence, ID: JCPP/Pars/1/1930. Cambridge: Jesus College, Cambridge. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Bulletin No. 8 (PDF) (Report). IAS Publications Collection. Princeton: Institute for Advanced Study. March 1939. p. 10. hdl:20.500.12111/5955. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ "Past Member: Albert E. Ingham". IAS. Princeton: Institute for Advanced Study. 1939. Archived from the original on 2 June 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Pars, Leopold Alexander. "About a job that A.E. Ingham was offered in America" (1942) [Letter]. Papers of Leopold Alexander Pars, Series: 161 letters, ID: JCPP/Pars/1/1942. Cambridge: Jesus College, Cambridge. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Pars, Leopold Alexander. "Letter from Pars's godson Michael Ingham and to him" (1980) [Letter]. Papers of Leopold Alexander Pars, Series: 235 letters, ID: JCPP/Pars/1/1973. Cambridge: Jesus College, Cambridge. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Polk's Princeton. Including Princeton Township. Princeton: R.L. Polk & Company. 1942. p. 108. OCLC 173860265.

- ^ Irvine, Lyn. "Letter to Hella Weyl" (22 August 1942) [Letter]. Papers of Lyn Newman, Series: Correspondence with Hella and Hermann Weyl, ID: GB 275 NewmanL/A/A2/Weyl/37. Cambridge: St John's College, Cambridge. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Newman, William (2002). "Married to a Mathematician: Lyn Newman's Life in Letters" (PDF). The Eagle. Cambridge: St John's College, Cambridge. 48: 47–55. OCLC 17524145. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ Burkill, John Charles (1981). "Ingham, Albert Edward". In Williams, Edgar Trevor; Nicholls, Christine Stephanie (eds.). Dictionary of National Biography 1961 – 1970. 8. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 563. ISBN 978-0198652076. OCLC 1038051360. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Ingham, Jane. "Letter to Lyn Newman" (1 March 1967) [Letter]. Papers of Lyn Newman, Series: Correspondence with Jane Ingham. ALS to Lyn Newman, ID: GB 275 NewmanL/A/A2/Ingham, J/2, p. 1. Cambridge: St John's College, Cambridge Library Special Collections. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Burkill, John Charles (2004). "Ingham, Albert Edward (1900-1967), mathematician". Maths History St Andrews. Revised by Paul Cohn. St Andrews: Oxford University Press. 34099. Archived from the original on 7 February 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Deaths". The Times (61338). London. 15 September 1982. p. 26. ISSN 0140-0460. Gale CS436701999. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Cambridge City Crematorium (20 September 1982). Cremation register scan (Register scan). Cremations 1 to 104,953, dated 21 December 1938 to 28 June 1996. Girton: Cambridge City Council. p. 1. 635576.

- ^ Pars, Leopold Alexander. "Death of Theodora Alberta Pars" (1980) [Letter]. Papers of Leopold Alexander Pars, Series: 218 letters, ID: JCPP/Pars/1/1980. Cambridge: Jesus College, Cambridge. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Pars, Leopold Alexander. "Letter from Michael Ingham" (1982) [Letter]. Papers of Leopold Alexander Pars, Series: 146 letters, ID: JCPP/Pars/1/1982. Cambridge: Jesus College, Cambridge. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Lamport, Derek Thomas Anthony (1965). "The Protein Component of Primary Cell Walls. I. Introduction. B. Historical Perspective 1888 to 1959". In Preston, Reginald Dawson (ed.). Advances in Botanical Research. 2. London: Academic Press. p. 152. OCLC 879904706. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ "University News. Leeds, June 28". The Times (44932). London. 29 June 1928. p. 18. ISSN 0140-0460. Gale CS302587613. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Mather, Joyce (3 July 1928). "Miss Tupper‑Carey's Degree". Leeds Mercury. Leeds. p. 4. OCLC 1016307518. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Preston, Reginald Dawson. "Reginald Dawson Preston correspondence and papers" (1995) [4 Boxes]. 1897 to 1995, ID: MS 1718. Leeds: University of Leeds. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Cushing, David (December 2005). "Reginald Dawson Preston. 21 July 1908 – 3 May 2000: Elected F.R.S. 1954". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. Lowestoft: Royal Society. 51: 347–353. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2005.0022. ISSN 0080-4606. JSTOR 30036901.

- ^ Priestley 1926, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Fowler, Stanley D.; Greenspan, Phillip (1 August 1985). "Application of Nile red, a fluorescent hydrophobic probe, for the detection of neutral lipid deposits in tissue sections: comparison with oil red O". Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. New York: The Histochemical Society. 33 (8): 833–836. doi:10.1177/33.8.4020099. ISSN 0022-1554. PMID 4020099. S2CID 10496865. Archived from the original on 7 November 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Pearsall & Ewing 1927, p. 252.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McPherson, D. C. (23 October 1939). "Cortical Air Spaces in the Roots of Zea mays". New Phytologist. London: Wiley-Blackwell. 38 (3): 190–202. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1939.tb07098.x. ISSN 1469-8137. JSTOR 2428235. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sifton, Harold Boyd (29 February 1940). "Lysigenous Air Spaces in the Leaf of Labrador Tea, Ledum Groenlandicum Oeder". New Phytologist. London: Wiley-Blackwell. 39 (1): 75–79. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1940.tb07122.x. ISSN 1469-8137. JSTOR 2428866. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Office of Experiment Stations (1924). "Recent Work in Agricultural Science. Agricultural Botany". Experiment Station Record. July to December 1924. Washington: Department of Agriculture. 51 (4): 330–331. ISSN 0097-689X. OCLC 869754915. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ "Societies and Academies. London. Royal Society". Nature. London: Nature Portfolio. 112 (2801): 26. 7 July 1923. Bibcode:1930Natur.125..621.. doi:10.1038/112026a0. ISSN 1476-4687. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ Tupper‑Carey & Priestley 1923, p. 110.

- ^ Zamil, Mohammad Shafayet; Geitmann, Anja (16 February 2017). "The middle lamella - more than a glue". Physical Biology. Bristol: IOP Publishing. 14 (1): 015004. doi:10.1088/1478-3975/aa5ba5. ISSN 1478-3975. PMID 28140367.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Halbsguth, Wilhelm (2020) [1965]. "3. Induktion von Dorsiventralität bei Pflanzen. 5. Krümmungen. e) Vergleich von Krümmungen und Dorsiventralität" [3. Induction of Dorsiventrality in Plants. 5. Curvatures. e) Comparison of Curvatures and Dorsiventrality]. In Ruhland, Wilhelm (ed.). Handbuch der Pflanzenphysiologie. Differenzierung und Entwicklung [Encyclopedia of Plant Physiology. Differentiation and Development]. Part III. Growth, Development, Movement (in German). 15/1. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. p. 370. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-36273-0_11. ISBN 978-3-662-36273-0. OCLC 913814739. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Kunze, Henning (1977). "Nutation und Wachstum III" [Nutation and Growth III]. Elemente der Naturwissenschaft [Elements of Science] (in German). Goetheanum: Natural Science Section at the Goetheanum (27): 1–11. doi:10.18756/EDN.27.1. OCLC 720264704. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Societies and Academies. Leeds. Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society". Nature. London: Nature Portfolio. 125 (3155): 622. 19 April 1930. Bibcode:1930Natur.125..621.. doi:10.1038/125621a0. ISSN 1476-4687. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sinnott, Edmund Ware (1960). "Part Two. The Phenomena of Morphogenesis. 6. Polarity". Plant Morphogenesis. 2. New York: Academic Press. pp. 128–129. hdl:2027/uc1.b3741908. OCLC 325141.

- ^ Philipson, William Raymond; Ward, Josephine Margaret; Butterfield, Brian Geoffrey (1971). "10. Experimental Control of Cambial Development". The Vascular Cambium: Its development and activity. London: Chapman & Hall. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-412-10400-8. OCLC 144649. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Hudson, Penrhyn Stanley (May 1931). "Imperial Bureau of Plant Genetics (for crops other than Herbage), Plant Breeding Institute, School of Agriculture, Downing Street, Cambridge, England". The Journal of the Ministry of Agriculture. Cambridge: HMSO. 38 (2): 138–142. OCLC 860139833. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Agricultural Research. A Development in Imperial Cooperation". Northern Whig. Belfast. 3 October 1930. p. 3. OCLC 867002267. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux". Nature. London: Nature Portfolio. 160 (4076): 824. 1 December 1947. Bibcode:1947Natur.160V.824.. doi:10.1038/160824f0. ISSN 1476-4687. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Ellerton, Sydney (2020). "Chapter 9: Clouds Loom Over England" (PDF). Sugar Beet and World Travel. A Short Autobiography of Dr Sydney Ellerton 1914 to 2011 (Booklet). Kew: Shôn Ellerton. p. 70. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ "The Empire Bureaux. Dissemination of Research Information". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. 30 September 1930. p. 5. ISSN 0307-5850. OCLC 624981792. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Tamm, Vali, ed. (2003). The Houghton Mifflin Dictionary of Biography. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-618-25210-7. OCLC 492007725. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^

Imperial Bureau of Plant Genetics (For Crops other than Herbage) (1930). "A bibliography of important works, principally for the period 1925 to 1930, but including some older works". Wheat Breeding Bibliography. Cambridge: School of Agriculture. 1–3: 1–68. OCLC 419296567.

Parts 1, 2, and Addenda. Mimeographed

- ^ "Book Review". Scientific Agriculture. Ottawa: Canadian Society of Technical Agriculturists. 20 (10): 596–598. June 1940. OCLC 220756836.

- ^ "List of Visitors to the Eighth Conference". Report of Proceedings. 8th Conference. London: Association of Special Libraries and Information Bureaux. 8: 9. September 1931. OCLC 706048068.

- ^ "A Key To Information. Value of Expert Translators". The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. Leeds. 26 September 1931. p. 8. ISSN 0963-1496. OCLC 18793101. Retrieved 26 December 2020 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Imperial Agricultural Bureaux (1936). "Imperial Bureau of Plant Genetics (for crops other than Herbage), Plant Breeding Institute, School of Agriculture, Downing Street, Cambridge, England". List of Agricultural Research Workers in the British Empire. Cambridge: HMSO: 7. hdl:2027/uiug.30112119601000. OCLC 1083223582.

- ^ Imperial Agricultural Bureaux (1940). "Tenth Annual Report 1938 to 1939". Imperial Agricultural Bureaux Annual Report of the Executive Council. London: HMSO. 10: 6. OCLC 950895993. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Phillimore, William Phillimore Watts; Fry, Edward Alex (1905). An index to Changes of name: Under authority of act of Parliament or Royal license, and including irregular changes from I George III to 64 Victoria, 1760 to 1901. London: Phillimore & Co. p. 322. OCLC 60736898. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ "I, Albert Darell Carey". The Times (32226). London. 10 November 1887. p. 1. ISSN 0140-0460. Gale CS17354090. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Priestley & Tupper‑Carey 1922, p. 210.

- ^ Balls, William Lawrence. "Referee's report on 'The composition of the cell-wall at the apical meristem of stem and root' by R. M. Tupper‑Carey and J. H. Priestley" (May 1923) [Item]. Referees' reports on scientific papers submitted to the Royal Society for publication, Series: Referees' reports: volume 29, peer reviews of scientific papers submitted to the Royal Society for publication, ID: RR/29/62, pp. 1–4. London: Royal Society. Retrieved 27 May 2021.

Bibliography[]

- Dieckert, Julius Walter; Snowden, James Ernest (1960). "Subcellular distribution of substances in seeds of Arachis hypogaea". Federation Proceedings. Bethesda: Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 19 (1): 126. OCLC 1569053. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- Imperial Bureau of Plant Genetics (For Crops other than Herbage) (1930). "The Imperial Bureau of Plant Genetics Staff". Plant Breeding Abstracts. Cambridge: School of Agriculture. 1–2: 2. OCLC 441661701.

- Kaldewey, Harald (June 1957). "Wachstumsverlauf, Wuchsstoffbildung und Nutationsbewegungen von Fritillaria meleagris L. im Laufe der Vegetationsperiode" [Growth Pattern, Growth Substance Formation and Nutation Movements of Fritillaria meleagris L. in the Course of the Vegetation Period]. Planta [Plant] (in German). Bonn: Springer Science+Business Media. 49 (3): 300–344. doi:10.1007/BF01911291. ISSN 1432-2048. JSTOR 23363315. S2CID 41817628.

- King, N. J.; Bayley, Stanley Thomas (August 1963). "A Chemical Study of the Cell Walls of Jerusalem Artichoke Tuber Tissue Under Different Growth Conditions". Canadian Journal of Botany. Ottawa: Canadian Science Publishing. 41 (8): 1141–1153. doi:10.1139/b63-094.

- Salisbury, Edward James (December 1916). "The Emergence of the Aerial Organs in Woodland Plants". Journal of Ecology. London: British Ecological Society. 4 (4): 121–128. doi:10.2307/2255627. ISSN 0022-0477. JSTOR 2255627. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- Tripp, Verne Wilken; Moore, Anna Theresa; Rollins, Mary Lockett (December 1951). "Some Observations on the Constitution of the Primary Wall of the Cotton Fibre". Textile Research Journal. Louisiana: SAGE Publishing. 21 (12): 886–894. doi:10.1177/004051755102101206. S2CID 97385847.

- Wood, Frederic M. (July 1926). "Further Investigations of the Chemical Nature of the Cell-membrane". Annals of Botany. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 40 (3): 547–570. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aob.a090037. ISSN 0305-7364. JSTOR 43236554. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

Further reading[]

- Blight, Denis; Ibbotson, Ruth (2011). Hemming, David (ed.). CABI: a century of scientific endeavour (PDF). CABI International. Malta: Gutenberg Press. ISBN 978-1-84593-873-4. OCLC 1040280202. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Lang, Cosmo Gordon (1945). Tupper (Canon A. D. Tupper‑Carey): A Memoir of a Very Human Parish Priest. London: Constable & Co. OCLC 931231033. Archbishop Lang's biography of Ingham's father, Canon A. D. Tupper‑Carey.

- Priestley, Joseph Hubert; Scott, Lorna Iris; Harrison, Edith (1964) [First published in 1938]. An Introduction to Botany, with special reference to the structure of the flowering plant. Illustrated by Marjorie Edith Malins and Lorna Iris Scott. London: Longmans Green & Co. OCLC 1150024139. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- Ede, Ronald, ed. (1930). "Members of Staff at the School of Agriculture, Downing Street, Cambridge". Cambridge University Agricultural Society Magazine. Vol. 3. Cambridge University Agricultural Society. Cambridge: W. Heffer & Sons. p. 74. OCLC 43472660.

Penrhyn Stanley Hudson and Tupper‑Carey are photographed seated together, on the left, at the front.

External links[]

- Portrait of Jane Tupper‑Carey by William Roberts, circa 1922, "An English Cubist".

- Afterimages: Photographs as an External Autobiographical Memory System and a Contemporary Art Practice, University of the Arts London Research Online. Photographs of Jane Ingham, taken by Albert Ingham, for Mark Ingham's PhD thesis at Goldsmiths, University of London.

- Works by Tupper‑Carey at WorldCat.

- Lorna Scott and her Mortar Board by Margaret Stewart, for Egham Museum, on botanist Lorna Scott, Joseph Hubert Priestley's collaborator after Tupper‑Carey left for Cambridge.

- 1897 births

- 1982 deaths

- 20th-century British botanists

- 20th-century British women scientists

- 20th-century English people

- 20th-century English women

- Academics of the University of Leeds

- Alumni of the University of Leeds

- British translators

- British women botanists

- English botanists

- German–English translators

- People from Leeds

- Women botanists