Jeanne de Clisson

show This article may be expanded with text translated from the corresponding article in Dutch. (January 2014) Click [show] for important translation instructions. |

Jeanne Louise de Belleville, de Clisson, Dame de Montaigu | |

|---|---|

Coat of Arms Clisson Family | |

| Born | 1300 |

| Died | 1359 Hennebont |

| Nationality | Brittany |

| Other names | Jeanne de Belleville |

| Spouse(s) | Geoffrey de Châteaubriant VIII Guy of Penthièvre Olivier de Clisson IV Sir Walter Bentley |

| Children | Olivier de Clisson |

| Piratical career | |

| Nickname | Lioness of Brittany |

| Type | Privateer |

| Allegiance | John IV, Duke of Brittany  |

| Years active | c. 1343 – c. 1356 |

| Commands | Black Fleet; My Revenge |

Jeanne de Clisson (1300–1359), also known as Jeanne de Belleville and the Lioness of Brittany, was a Breton former noblewoman who became a privateer to avenge her husband after he was executed for treason by the French king. She crossed the English Channel targeting French ships and often slaughtering their crew. It was her practice to leave at least one sailor alive to carry her message to the King of France.

Early life[]

Jeanne Louise de Belleville, de Clisson, Dame de Montaigu, was born in 1300 in Belleville-sur-Vie in the Vendée, a daughter of nobleman Maurice IV Montaigu of Belleville and Palluau (1263–1304) and Létice de Parthenay of Parthenay (1276–?) in the Gâtine Vendéenne.

Marriage[]

In 1312, Jeanne married her first husband, 19-year-old Geoffrey de Châteaubriant VIII (died 1326), a Breton nobleman, and had two children:

- Geoffrey IX (1314–1347), inherited his father's estates as Baron, died in the Battle of La Roche-Derrien; and

- Louise (1316–1383), married Guy XII de Laval and subsequently inherited her brother's estate as Baroness.

Second marriage[]

In 1328, Jeanne married of the counts and dukes of Penthièvre, widower of Joan of and son of the Duke of Brittany. Jeanne may have done this to protect her underage children.

Intrigue and Annulment[]

The union was short-lived, as relatives of the Ducal family—in particular, from the de Blois faction—laid a complaint with the bishops of Vannes and Rennes to protect their heritage, and an investigation was conducted on February 10, 1330, resulting in the marriage being annulled by Pope John XXII.

Guy then married into the de Blois faction to Marie de Blois, who was also a niece of Phillip VI of France. Guy, however, unexpectedly died on 26 March 1331, and his heritage passed to his daughter Jeanne of Penthièvre.

Third marriage[]

In 1330, Jeanne married Olivier de Clisson IV, a wealthy Breton, holding a castle at Clisson, a manor house in Nantes and lands at Blain. Olivier was initially married to Blanche de Bouville (died 1329).

Jeanne, a recent widow herself of the lord of Chateaubriant, controlled areas in Poitou just south of the Breton border from Beauvoir-sur-Mer in the west to in the southeast of Clisson. Combining these assets would make Jeanne and Olivier the seigneurial power (senior Lord of an area) in the marches. Jeanne and Olivier eventually had five children:

- Isabeau, (1325–1343) born out of wedlock, married John I of Rieux and therefore mother of Jean II de Rieux (died 1343) and

- Maurice, (1333–1334, in Blain)

- Olivier V, (1336–1407), his father's successor, a future Constable of France, and nicknamed the butcher.

- Guillaume, (1338–1345) died of exposure

- Jeanne, (1340–?) married Jean Harpedane, Lord of Montendre IV's successor.

De Clissons choose sides[]

During the Breton War of Succession, the de Clissons sided with the French choice for the empty Breton ducal crown, Charles de Blois, against the English preference, John de Montfort.

The extended de Clisson family was not in full agreement in this matter, and Olivier IV's brother, Amaury de Clisson, embraced the de Montfort party.

Intrigue of Vannes[]

In 1342, the English, after four attempts, captured the city of Vannes. Jeanne's husband Olivier and Hervé VII de Léon, the military commanders defending this city, were captured.

Olivier was the only one released after an exchange for Ralph de Stafford, 1st Earl of Stafford (a prisoner of the French), and a surprisingly low sum was demanded.

This led Olivier to be subsequently suspected of not having defended the city to his fullest, and was alleged by Charles de Blois to be a traitor.

Tournament and trial[]

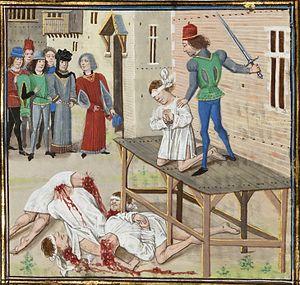

On 19 January 1343, the Truce of Malestroit was signed between England and France. Under the perceived safe conditions of this truce, Olivier and fifteen other Breton lords were invited to a tournament on French soil, where he was subsequently arrested, taken to Paris, tried by his peers and on 2 August 1343, executed by beheading at Les Halles.

In the year of our Grace one thousand three hundred and forty-three, on Saturday, the second day of August, Olivier, Lord of Clisson, knight, prisoner in the Chatelet of Paris for several treasons and other crimes perpetrated by him against the king and the crown of France, and for alliances that he made with the king of England, enemy of the king and kingdom of France, as the said Olivier ... has confessed, was by judgement of the king given at Orleans drawn from the to Les Halles ... and there on a scaffold had his head cut off. And then from there his corpse was drawn to the gibbet of Paris and there hanged on the highest level; and his head was sent to Nantes in Brittany to be put on a lance over the gate as a warning to others.[1]

This execution shocked the nobility as the evidence of guilt was not publicly demonstrated, and the process of desecrating/exposing a body was reserved mainly for low-class criminals. This execution was judged harshly by Froissart and his contemporaries.[2]

Shock and revenge[]

Jeanne took her two young sons, Olivier and Guillaume, from Clisson to Nantes, to show them the head of their father at the Sauvetout gate.

Jeanne, enraged by her husband's execution, swore retribution against the French King, Philip VI, and Charles de Blois. She considered their actions a cowardly murder.[3]

Change of allegiances[]

Jeanne then sold the de Clisson estates, raised a force of loyal men and started attacking French forces in Brittany.[3] Jeanne is said to have attacked:

- A castle at Touffou, near Bonnes.

- A castle occupied by Galois de la Heuse, an officer of Charles de Blois, massacring the entire garrison with the exception of one individual.

- A garrison at Château-Thébaud, about 20 km south east of Nantes, which had been a former post under control of her husband.

Black Fleet[]

With the English king's assistance and Breton sympathizers, Jeanne outfitted three warships.[4][5] These were painted black and their sails dyed red.[3][4] The flagship was named My Revenge.

The ships of this Black Fleet then patrolled the English Channel hunting down French ships, whereupon her force would kill entire crews, leaving only a few witnesses to transmit the news to the French King.[3] This earned Jeanne the moniker "The Lioness of Brittany".[3][5] Jeanne continued her piracy in the channel for another 13 years.[5]

Jeanne is also said to have attacked coastal villages in Normandy and have put several to sword and fire.

In 1346, during the Battle of Crécy, south of Calais, in northern France, Jeanne used her ships to supply the English forces.

After the sinking of her flagship, Jeanne with her two sons were adrift for five days; her son Guillaume died of exposure. Jeanne and Olivier were finally rescued and taken to Morlaix by Montfort supporters.

Fourth marriage[]

In 1356, Jeanne married for a fourth time to Walter Bentley, one of King Edward III's military deputies during the campaign. Bentley had previously won the battle of Mauron on 4 August 1352 and was rewarded for his services with "the lands and castles" Beauvoir-sur-mer, of Ampant, of Barre, Blaye, Châteauneuf, Ville Maine, the island Chauvet and from the islands of Noirmoutier and Bouin.[6]

Jeanne finally settled at the Castle of Hennebont, a port town on the Brittany coast, which was in the territory of her de Montfort allies, where she died in 1359.

Historical evidence[]

Verifiable references relating to Jeanne’s exploits are limited, but do exist. These include:

- A French judgement from 1343 convicting Jeanne as a traitor and confirming the confiscation of the de Clisson lands.

- Records from the English court from 1343, indicating King Edward granting Jeanne an income from lands controlled in Brittany by the English.

- Jeanne is mentioned in the truce between France and England in 1347 as an English ally. (Treaty of Calais, 28 September 1347)[7]

- A 15th-century manuscript, known as the Chronographia Regum Francorum, confirms some of the details of her life.[8]

- Amaury de Clisson, the brother of Olivier, is used as an emissary from Joanna of Flanders (Jehanne de Montfort) to ask King Edward III for aid to relieve Hennebont. The de Clisson family was at that stage definitely on the de Montfort side.

- Records exist where shortly after Olivier de Clisson's execution, several other knights were accused of similar crimes. The lord of Malestroit and his son, the lord of Avaugour, sir Tibaut de Morillon, and other lords of Brittany, to the number of ten knights and squires, were beheaded at Paris. Four other knights of Normandy, sir William Baron, sir Henry de Malestroit, the lord of Rochetesson, and Sir Richard de Persy, were put to death upon reports.

- The name of Jeanne de Belleville is also attached to the Breviary of Belleville, a book of prayers that follow the liturgical year. This manuscript in Latin and in French and in two volumes dated around 1323–1326 with illuminations by Jean Pucelle. Jeanne de Belleville would have received it as a gift for her wedding with Olivier. Around 1379–1380, an inventory was made of King Charles V's property, and the breviary was described herein.

- Great Chronicles of France, t.5, of John (II) the Good to Charles (V) the Wise (1350/1380);

- Latin chronicle of Guillaume de Nangis and his continuations, (1317/1368);

- Chronicles of the first four Valois, (1327/1393)

- Chronicles of Mont-Saint-Michel, t.1 (1343/1432)

Literature[]

In 1868, French writer Émile Pehant's novel Jeanne de Belleville was published in France. Written at the height of the French romantic movement, Pehant's novel shares many details with the legend attached to Jeanne.

See also[]

- Olivier de Clisson, V, her son

- Belleville Breviary, a book of prayers

References[]

- ^ The Law of Treason and Treason Trials in Later Medieval France (Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought: Third Series). 18 December 2003

- ^ "The Online Froissart". www.hrionline.ac.uk.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Duncombe, Laura (1 April 2017). Pirate Women: The Princesses, Prostitutes, and Privateers Who Ruled the Seven Seas. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 9781613736043 – via Google Books.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vencel, Wendy (1 January 2018). "Women at the Helm: Rewriting Maritime History through Female Pirate Identity and Agency". Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Vázquez, Germán (2004). Mujeres Piratas. EDAF. ISBN 9788496107267 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Battle of Mauron, 14 August 1352 (Brittany)". www.historyofwar.org.

- ^ Wagner, J. A. Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War ISBN 0-313-32736-X, Greenwood Press, 2006

- ^ Régis Rech. "Chronographia regum Francorum". Encyclopedia of the Medieval Chronicle. Edited by Graeme Dunphy. Brill Online, 2014. 30 October 2014

Further reading[]

- d'Eaubonne, Françoise (1998), Les grandes aventurieres (in French), Saint-Amard-Montrond: Vernal and Philippe Lebaud, pp. 17–27, ISBN 2865940381

- Hearst, Michael (2015), Extraordinary People, San Francisco: Chronicle, pp. 28–29, ISBN 978-1-4521-2709-5

- Froissart, Jean; Scheler, Auguste (1875), Oeuvres de Froissart: publiées avec les variantes des divers manuscrits, 21, p. 12

- Henneman, John Bell (June 1996), Olivier de Clisson and political society in France under Charles V and Charles VI, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

- Jaeger, Gérard A. (1984), Les femmes d'abordage: Chroniques historiques et legendaires des aventurières de la mer, Paris: Clancier-Guénaud, pp. 31–39

- Lapouge, Gilles (1987), Les Pirates, forbans, flibustiers, boucaniers et autres gueux de mer

- Gicquel, Yvonig (1981), Olivier de Clisson, connétable de France ou chef de parti breton?, París: Jean Picollec, pp. 39–41, ISBN 2-86477-025-3

- Richard, Philippe (2007), Olivier de Clisson, connétable de France, grand seigneur breton, Haute-Goulaine: Ediciones Opéra, pp. 39–43, ISBN 978-2-35370-030-1

- Robbins, Trina (2004), Wild Irish Roses: Tales of Brigits, Kathleens, and Warrior Queens, Conari Press, pp. 115–116, ISBN 1-57324-952-1

- de Tourville, Anne (1958), Femmes de la mer, Paris: Le Livre Contemporain, pp. 37–47

- Vázquez Chamorro, Germán (October 2004), "Jeanne de Classon. La leona sangrienta", Mujeres Piratas (in Spanish), Algaba, pp. 107–115, ISBN 84-96107-26-4

- Sténuit, Marie-Ève (2015), pirates Women: the foamy sea (in French), ISBN 979-1-09-153415-4

External links[]

- 1300 births

- 1359 deaths

- 14th-century French people

- 14th-century French women

- Female pirates

- Medieval pirates

- People from Loire-Atlantique

- People of the Hundred Years' War

- Women in 14th-century warfare

- Women in war in France