Jose P. Laurel

José P. Laurel | |

|---|---|

| |

| 3rd President of the Philippines[a] | |

| In office October 14, 1943 – August 17, 1945 | |

| Prime Minister | Jorge B. Vargas |

| Preceded by | Manuel L. Quezon[d] |

| Succeeded by | Sergio Osmeña[e] |

| Commissioner of the Interior | |

| In office December 4, 1942 – October 14, 1943 | |

| Presiding Officer, PEC | Jorge B. Vargas |

| Preceded by | Benigno Aquino Sr. |

| Succeeded by | Quintin Paredes |

| Commissioner of Justice | |

| In office December 24, 1941 – December 4, 1942 | |

| Presiding Officer, PEC | Jorge B. Vargas |

| Preceded by | Teófilo Sison |

| Succeeded by | Teófilo Sison |

| Senator of the Philippines | |

| In office December 30, 1951 – December 30, 1957 | |

| 34th Associate Justice of the Philippine Supreme Court | |

| In office February 29, 1936 – February 5, 1942 | |

| Appointed by | Manuel L. Quezon |

| Preceded by | George Malcolm |

| Succeeded by | Court reorganized |

| Majority leader of the Senate of the Philippines | |

| In office 1928–1931 | |

| Senate President | Manuel L. Quezon |

| Preceded by | Francisco Enage |

| Succeeded by | Benigno S. Aquino |

| Senator of the Philippines from the 5th district | |

| In office 1925 – 1931 Served with: Manuel L. Quezon (1925–1931) | |

| Preceded by | Antero Soriano |

| Succeeded by | Claro M. Recto |

| Secretary of the Interior of the Philippines | |

| In office 1922–1923 | |

| Preceded by | Teodoro M. Kalaw |

| Succeeded by | Felipe Agoncillo |

| Personal details | |

| Born | José Paciano Laurel y García March 9, 1891 Tanauan, Batangas, Captaincy General of the Philippines |

| Died | November 6, 1959 (aged 68) Manila, Philippines |

| Resting place | Tanauan, Batangas, Philippines |

| Political party | Nacionalista |

| Other political affiliations | KALIBAPI (1942–1945) |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | José B. Laurel Jr. José S. Laurel III Natividad Laurel-Guinto Sotero Laurel II Mariano Laurel Rosenda Laurel-Avanceña Potenciana Laurel-Yupangco Salvador Laurel Arsenio Laurel |

| Education | University of the Philippines, Diliman (LLB) University of Santo Tomas (LLM) Yale University (SJD) |

| Signature | |

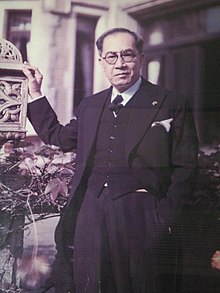

José Paciano Laurel y García CCLH (March 9, 1891 – November 6, 1959) was a Filipino politician and judge, who served as the president of the Japanese-occupied Second Philippine Republic, a puppet state when during World War II, from 1943 to 1945. Since the administration of President Diosdado Macapagal (1961–1965), Laurel has been officially recognized by later administrations as a former president of the Philippines.

Early life and career[]

José Paciano Laurel y García was born on March 9, 1891 in the town of Tanauan, Batangas. His parents were Sotero Laurel I and Jacoba García. His father had been an official in the revolutionary government of Emilio Aguinaldo and a signatory to the 1899 Malolos Constitution.

While a teen, Laurel was indicted for attempted murder when he almost killed a rival suitor of the girl he stole a kiss from with a fan knife. While studying and finishing law school, he argued for and received an acquittal.[1]

Laurel received his law degree from the University of the Philippines College of Law in 1915, where he studied under Dean George A. Malcolm, whom he would later succeed on the Supreme Court. He then obtained a Master of Laws degree from University of Santo Tomas in 1919. Laurel then attended Yale Law School, where he obtained his J.S.D. degree.

Laurel began his life in public service while a student, as a messenger in the Bureau of Forestry then as a clerk in the Code Committee tasked with the codification of Philippine laws. During his work for the Code Committee, he was introduced to its head, Thomas A. Street, a future Supreme Court Justice who would be a mentor to the young Laurel.[2]

Upon his return from Yale, Laurel was appointed first as Undersecretary of the Interior Department, then promoted as Secretary of the Interior in 1922. In that post, he would frequently clash with the American Governor-General Leonard Wood, and eventually, in 1923, resign from his position together with other Cabinet members in protest of Wood's administration. His clashes with Wood solidified Laurel's nationalist credentials.

Laurel was a member of the Philippine fraternity Upsilon Sigma Phi.[3]

Senator and Congressman of the Philippines[]

In 1925 Laurel was elected to the Philippine Senate. He would serve for one term before losing his re-election bid in 1931 to Claro M. Recto.[4] He retired to private practice, but by 1934, he was again elected to public office, this time as a delegate to the 1935 Constitutional Convention. Hailed as one of the "Seven Wise Men of the Convention", he would sponsor the provisions on the Bill of Rights.[4] Following the ratification of the 1935 Constitution and the establishment of the Commonwealth of the Philippines, Laurel was appointed Associate Justice of the Supreme Court on February 29, 1936.

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court[]

Laurel's Supreme Court tenure may have been overshadowed by his presidency, yet he remains one of the most important Supreme Court justices in Philippine history. He authored several leading cases still analyzed to this day that defined the parameters of the branches of government as well as their powers.

Angara v. Electoral Commission, 63 Phil. 139 (1936), which is considered as the Philippine equivalent of Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803), is Laurel's most important contribution to jurisprudence and even the rule of law in the Philippines. In affirming that the Court had jurisdiction to review the rulings of the Electoral Commission organized under the National Assembly, the Court, through Justice Laurel's opinion, firmly entrenched the power of Philippine courts to engage in judicial review of the acts of the other branches of government, and to interpret the Constitution. Held the Court, through Laurel:

The Constitution is a definition of the powers of government. Who is to determine the nature, scope and extent of such powers? The Constitution itself has provided for the instrumentality of the judiciary as the rational way. And when the judiciary mediates to allocate constitutional boundaries, it does not assert any superiority over the other departments; it does not in reality nullify or invalidate an act of the legislature, but only asserts the solemn and sacred obligation assigned to it by the Constitution to determine conflicting claims of authority under the Constitution and to establish for the parties in an actual controversy the rights which that instrument secures and guarantees to them.[5]

Another highly influential decision penned by Laurel was Ang Tibay v. CIR, 69 Phil. 635 (1940). The Court acknowledged in that case that the substantive and procedural requirements before proceedings in administrative agencies, such as labor relations courts, were more flexible than those in judicial proceedings. At the same time, the Court still asserted that the right to due process of law must be observed, and enumerated the "cardinal primary rights" that must be respected in administrative proceedings. Since then, these "cardinal primary rights" have stood as the standard in testing due process claims in administrative cases.

Calalang v. Williams, 70 Phil. 726 (1940) was a seemingly innocuous case involving a challenge raised by a private citizen to a traffic regulation banning kalesas from Manila streets during certain afternoon hours. The Court, through Laurel, upheld the regulation as within the police power of the government. But in rejecting the claim that the regulation was violative of social justice, Laurel would respond with what would become his most famous aphorism, which is to this day widely quoted by judges and memorized by Filipino law students:

Social justice is neither communism, nor despotism, nor atomism, nor anarchy, but the humanization of laws and the equalization of social and economic forces by the State so that justice in its rational and objectively secular conception may at least be approximated. Social justice means the promotion of the welfare of all the people, the adoption by the Government of measures calculated to insure economic stability of all the competent elements of society, through the maintenance of a proper economic and social equilibrium in the interrelations of the members of the community, constitutionally, through the adoption of measures legally justifiable, or extra-constitutionally, through the exercise of powers underlying the existence of all governments on the time-honored principle of salus populi est suprema lex. Social justice, therefore, must be founded on the recognition of the necessity of interdependence among divers and diverse units of a society and of the protection that should be equally and evenly extended to all groups as a combined force in our social and economic life, consistent with the fundamental and paramount objective of the state of promoting the health, comfort, and quiet of all persons, and of bringing about "the greatest good to the greatest number.[6]

Presidency[]

| Presidential styles of Jose P. Laurel | |

|---|---|

| Reference style | His Excellency[7] |

| Spoken style | Your Excellency |

| Alternative style | Mr. President |

The presidency of Laurel understandably remains one of the most controversial in Philippine history. After the war, he would be denounced by the pro-American sectors[who?] as a war collaborator or even a traitor, although his indictment for treason was superseded by President Roxas' Amnesty Proclamation.[8] However, despite being one of the most infamous figures in Philippine history, he is also regarded as a Pan-Asianist who supported independence. When asked if he was pro-American or pro-Japanese, his answer would be pro-Filipino.[citation needed]

Accession[]

When Japan invaded, President Manuel L. Quezon first fled to Bataan and then to the United States to establish a government-in-exile. Quezon ordered Laurel, Vargas and other cabinet members to stay. Laurel's prewar, close relationship with Japanese officials (a son had been sent to study at the Imperial Japanese Army Academy in Tokyo, and Laurel had received an honorary doctorate from Tokyo University), placed him in a good position to interact with the Japanese occupation forces.

Laurel was among the Commonwealth officials instructed by the Japanese Imperial Army to form a provisional government when they invaded and occupied the country. He cooperated with the Japanese, in contrast to Chief Justice Abad Santos, who was shot for refusing to cooperate.[9] Because he was well known to the Japanese as a critic of US rule, as well as having demonstrated a willingness to serve under the Japanese Military Administration, he held a series of high posts in 1942–1943. Under vigorous Japanese influence, the National Assembly selected Laurel to serve as president in 1943.

Domestic Problems[]

Economy[]

During Laurel's tenure as president, hunger was the main worry. Prices of essential commodities rose to unprecedented heights. The government exerted every effort to increase production and bring consumers' goods under control. However, Japanese rapacity had the better of it all. On the other hand, guerrilla activities and Japanese retaliatory measures brought the peace and order situation to a difficult point. Resorting to district-zoning and domiciliary searches, coupled with arbitrary arrests, the Japanese made the mission of Laurel's administration incalculably exasperating and perilous.[10]

Food shortage[]

During his presidency, the Philippines faced a crippling food shortage which demanded much of Laurel's attention.[11] Rice and bread were still available but the sugar supply was gone.[12] Laurel also resisted Japanese demands that the Philippines issue a formal declaration of war against the United States. He later was forced to declare war on the US and Great Britain as long as Filipinos would not have to fight.

Foreign policies[]

Philippine-Japanese Treaty of Alliance[]

On October 20, 1943, the Philippine-Japanese Treaty of Alliance was signed by Claro M. Recto, who was appointed by Laurel as his Foreign Minister, and Japanese Ambassador to Philippines Sozyo Murata. One redeeming feature was that no conscription was envisioned.[10]

Greater East Asia Conference[]

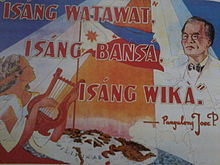

Shortly after the inauguration of the Second Philippine Republic, President Laurel, together with cabinet Ministers Recto and Paredes flew to Tokyo to attend the Greater East Asia Conference which was an international summit held in Tokyo, Japan from November 5 – 6, 1943, in which Japan hosted the heads of state of various component members of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. The conference was also referred to as the Tokyo Conference.

The Conference addressed few issues of any substance, Eradication of Western Opium Drug Trade and to illustrate the Empire of Japan's commitments to the Pan-Asianism ideal and to emphasize its role as the "liberator" of Asia from Western colonialism.[13]

Martial law[]

Laurel declared the country under martial law in 1944 through Proclamation No. 29, dated September 21.[14] Martial law came into effect on September 22, 1944 at 9 am.[citation needed] Proclamation No. 30 was issued the next day, declaring the existence of a state of war between the Philippines and the United States and the United Kingdom. This took effect on September 23, 1944 at 10:00 A.M.[15]

Filipinization of the Catholic Church[]

On the day of his inauguration, Laurel sought to gain recognition for the new republic from the Holy See. Correspondence between the diplomats of the Vatican and Japan told that the Holy See did not wish to recognize any new states for the duration of the War. Despite this, Laurel still sought to appeal to the Pope about instating Filipinos into the Church hierarchy.[16]

As the Head of the Republic of Philippines,' I take liberty of voicing to Your Holiness the desire and sentiments of eighteen million Filipinos, the majority of whom are ardent Catholics, with respect to the matter which vitally affects the administration of the Catholic Church in Philippines, and which may have far reaching effects on their religious faith. I refer to Filipinization of the Catholic hierarchy and clergy in Philippines.

Your Holiness will remember that the movement for Filipinization of the clergy furnished one of the prime motivations of our revolution against Spain; that with overthrow of Spanish sovereignty only 250 out of 17,000 Spanish friars assigned to Philippines in 1898 were retained; that pursuant to the policy announced by the Holy See, Spanish bishops were replaced by American Catholic bishops; that during the American regime more missionaries of different nationalities came to the country; and that at present we have five Bishops and two Apostolic Prefects of foreign nationalities, while in certain provinces, such as Surigao, Agusan, Antique, Misamis Oriental, Mindoro, Bukidnon, Davao, Cotabato, Palawan and Mountain Province, parishes are still under the charge of foreign friars and missionaries. Now that the independence of Philippines has been finally achieved, the Republic of Philippines, though it fundamentally recognizes the separation of Church and State, can no longer remain indifferent to a long-felt need to Filipinize the local Catholic hierarchy and clergy.

In advocating this reform, the Filipino people are not moved by any spirit of animosity or hostility against any race or nationality, but they are inspired solely by the desire to win a just recognition for the Filipino race in their own country and to secure a vindication of capacity of Filipinos to manage their own affairs, temporal or spiritual. The projected measure can be achieved without in the least prejudicing interests, or sacrificing the creed or doctrines of the Roman Catholic Church. Without in any way presuming to invade an ecclesiastical jurisdiction in Philippines, it is my honest belief that the spread of Catholicism among our non-Christian brethren and consequently increase of its followers in this country. This, in my opinion, is in consonance with the desire of His Holiness Pope Pius XI when he said:

«From the fact that the Roman Pontiff has entrusted to you and to your helpers a task of preaching Christian religion to pagan nations, you ought not to conclude that the role of native clergy is solely that of assisting missionaries in minor matters and in some sort of completing their work».

What is the object of these holy missions, we ask, except that the Church of Christ may be instituted and established in those boundless regions? And from what shall the Church be built up today among heathens, except from those elements out of which it was built up among us that is unless it is composed of people, clergy and religious men and women recruited from their own country? Why should native clergy be prevented from cultivating their country which is their own native soil that is, from governing their own people? In propagation of Faith, a Filipino priest, by reason of his birth and temper, his sentiments and interests, is in far better position to carry on his mission than a stranger. As a matter of fact, he would know better than any foreigner the best method of approach to his own people and thus he would often have access where an alien priest could never gain an entrance. Moreover foreign missionaries, on account of their imperfect knowledge of Filipino language, are frequently prevented from expressing themselves fully and having themselves clearly understood, as a result of which, force and efficacy of their teachings are greatly weakened. It will also be a source of genuine satisfaction and lasting inspiration for Filipino people to see a Filipino at the head of the Catholic Church in Philippines, a Filipino priest in every parish and a Filipino missionary in every remote corner of the country. Certainly, it will foster development of national clergy of superior stamp and it will serve as an ideal incentive for Filipino clergy to work to the highest degree of perfection and the same time to encourage vocations to religious and sacerdotal life.

In view of foregoing considerations, I beg to convey and reiterate the desire and request of my people that it is, as it has always been, their cherished hope that after more than four centuries of Catholicism in Philippines, Your Holiness will see the wisdom of principle invoked and grant their petition for complete Filipinization of Catholic hierarchy and clergy in their own country.

— Jose P. Laurel, President of the Philippines to Pope Pius XII

Resistance[]

Due to the nature of Laurel's government and its connection to Japan, much of the population actively resisted his presidency,[17] supporting the exiled Commonwealth government;[18] as can be expected. However, this did not mean that his government did not have forces against the anti-Japanese resistance and the ongoing Philippine Commonwealth military.[18]

Assassination attempt[]

On June 5, 1943, Laurel was playing golf at the Wack Wack Golf and Country Club in Mandaluyong when he was shot around four times with a .45 caliber pistol.[19] The bullets barely missed his heart and liver.[19] He was rushed by his golfing companions, among them FEU president Nicanor Reyes Sr., to the Philippine General Hospital where he was operated by the Chief Military Surgeon of the Japanese Military Administration and Filipino surgeons.[19] Laurel enjoyed a speedy recovery.

Two suspects to the shooting were reportedly captured and swiftly executed by the Kempetai.[20] Another suspect, a former boxer named Feliciano Lizardo, was presented for identification by the Japanese to Laurel at the latter's hospital bed, but Laurel then professed unclear memory.[20] However, in his 1953 memoirs, Laurel would admit that Lizardo, by then one of his bodyguards who had pledged to give his life for him, was indeed the would-be-assassin.[20] Still, the historian Teodoro Agoncillo in his book on the Japanese occupation, identified a captain with a guerilla unit as the shooter.[20]

Dissolution of the regime[]

On July 26, 1945, the Potsdam Declaration served upon Japan an ultimatum to surrender or face utter annihilation. The Japanese government refused the offer. On August 6, 1945, Hiroshima, with some 300,000 inhabitants, was almost totally destroyed by an atomic bomb dropped from an American plane. Two days later, the Soviet Union declared war against Japan and invaded Manchuria.[21] The next day, August 9, 1945, a second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki. The Allied Forces' message now had a telling effect: Japan unconditionally surrendered to the Allied Powers on August 15, 1945.[10]

Since April 1945, President Laurel, together with his family and Cabinet member Camilo Osías, Speaker Benigno Aquino Sr., Gen. Tomas Capinpin, and Ambassador Jorge B. Vargas, had been in Japan. Evacuated from Baguio shortly after the city fell, they traveled to Aparri and thence, on board Japanese planes, had been taken to Japan. Laurel was put in Sugamo Prison then was later transferred to Nara for house arrest. On August 17, 1945, from Nara Hotel in Nara, Japan, President Laurel issued an Executive Proclamation which declared the dissolution of his regime.[10]

President Laurel is the only Philippine president who served the three branches of government. He became a senator-congressman, associate justice and a president of the second republic.

Post-presidency[]

1949 presidential election[]

On September 2, 1945, the Japanese forces formally surrendered to the United States. Gen. Douglas MacArthur ordered Laurel arrested for collaborating with the Japanese. In 1946 he was charged with 132 counts of treason, but he was never brought to trial due to the general amnesty granted by President Manuel Roxas in 1948.[8] Laurel ran for president against Elpidio Quirino in 1949 but lost in what future Secretary of Foreign Affairs Carlos P. Romulo and Marvin M. Gray considered as the dirtiest election in Philippine electoral history.[22]

Return to the senate[]

Laurel garnered the biggest votes and was elected to the Senate in 1951, under the Nacionalista Party. He was urged to run for president in 1953, but declined, working instead for the successful election of Ramon Magsaysay. Magsaysay appointed Laurel head of a mission tasked with negotiating trade and other issues with United States officials, the result being known as the Laurel–Langley Agreement.

Retirement and death[]

Laurel considered his election to the Senate as a vindication of his reputation. He declined to run for re-election in 1957. He retired from public life, concentrating on the development of the Lyceum of the Philippines established by his family.

During his retirement, Laurel stayed in a 1957 3-story, 7-bedroom mansion in Mandaluyong, dubbed "Villa Pacencia" after Laurel's wife. The home was one of three residences constructed by the Laurel family, the other two being in Tanauan, Batangas and in Paco, Manila (called "Villa Peñafrancia"). In 2008, the Laurel family sold "Villa Pacencia" to Ex-Senate President Manny Villar and his wife Cynthia.[23]

On November 6, 1959, Laurel died at the Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital in Santa Mesa, Manila,[24] from a massive heart attack and a stroke. He is buried in Tanauan, Batangas.

Honors[]

National Honor

: Philippine Legion of Honor, Chief Commander - (1959)

: Philippine Legion of Honor, Chief Commander - (1959)

Personal life[]

He married Pacencia Hidalgo on April 9, 1911.[25] The couple had nine children:

- José Laurel Jr. (August 27, 1912 – March 11, 1998), member of the Philippine National Assembly from Batangas from 1943 to 1944, Congressman from Batangas's third district from 1941 to 1957 and from 1961 to 1972, Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines from 1954 to 1957 and from 1967 to 1971, Assemblyman of Regular Batasang Pambansa from 1984 to 1986, Member of the Philippine Constitutional Commission of 1986 from June 2 to October 15, 1986 and a running-mate of Carlos P. Garcia of the Nacionalista Party in Philippine presidential election of 1957, placed second in the vice-presidential race against Diosdado Macapagal of Liberal Party (Philippines)

- José Laurel III (August 27, 1914 – January 6, 2003) ambassador to Japan

- Natividad Laurel (born December 25, 1916)

- Sotero Laurel II (September 27, 1918 – September 16, 2009) Senator of the Philippines from 1987 to 1992 became Senate President pro tempore from 1990 to 1992

- Mariano Antonio Laurel (January 17, 1922 – August 2, 1979)[26][27]

- Rosenda Pacencia Laurel (born January 9, 1925)

- Potenciana "Nita" Laurel Yupangco (born May 19, 1926)

- Salvador Laurel (November 18, 1928 – January 27, 2004) Senator of the Philippines from 1967 to 1972, Prime Minister of the Philippines from February 25 to March 25, 1986, Secretary of Foreign Affairs of the Philippines from March 25, 1986 to February 2, 1987, Vice President of the Philippines from February 25, 1986 to June 30, 1992 and a presidential candidate of the Nacionalista Party in Philippine presidential election of 1992 placed seventh in the presidential race against Fidel V. Ramos

- Arsenio Laurel (December 14, 1931 – November 19, 1967) He was the first two-time winner of the Macau Grand Prix, winning it consecutively in 1962 and 1963.

Descendants[]

- Roberto Laurel, grandson, President of Lyceum of the Philippines University-Manila and Lyceum of the Philippines University-Cavite, son of Sotero Laurel (3rd son of José P. Laurel)

- Peter Laurel, grandson, President of Lyceum of the Philippines University-Batangas and Lyceum of the Philippines University-Laguna

- Carlos "Chuck" Perez Laurel, grandson

- Luis Marcos "Mark" Laurel, grandson, lawyer, son of Sotero Laurel (3rd son of José P. Laurel)

- Jose Bayani "JB" Laurel Jr., UNIDO Party list, grandson

- José Laurel IV, grandson, representative of the 3rd district of Batangas, son of Jose Laurel Jr.

- Francis Castillo-Laurel, grandson

- Antonio "Tony" Castillo-Laurel, grandson

- Jose "Joey" C. Laurel V, grandson, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary, Philippine Ambassador to Japan

- Mercedes "Ditas" Laurel-Marquez, granddaughter

- Maria Elena "Marilen" Laurel-Loinaz, granddaughter

- Christine C. Laurel, granddaughter

- Benjamin "Benjie" C. Laurel+, grandson

- Eduardo C. Laurel+, grandson

- Susanna "Susie" D. Laurel-Delgado, granddaughter

- Celine "Lynnie" D. Laurel-Castillo

- Victor "Cocoy" D. Laurel, actor and singer

- Iwi Laurel-Asensio, granddaughter, singer and entrepreneur

- Patty Laurel, granddaughter, TV host and former MTV VJ

- Camille Isabella I. Laurel, UNIDO Party list, great-granddaughter

- Ann Maria Margarette I. Laurel great-grand daughter

- Jose Antonio Miguel I. Laurel, great-grandson

- Franco Laurel, great-grandson, singer and actor

- Rajo Laurel, great-grandson, fashion designer

- Denise Laurel, great-granddaughter, actress and singer

- Nicole Laurel Asensio, great-granddaughter, lead singer of General Luna band.

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ Retroactively recognized a legitimate President of the Philippines.

- ^ Manuel L. Quezon served as president of the government in exile

- ^ Sergio Osmeña served as president of the government in exile

- ^ As per the official chronological list of Presidents by the cotemporary Philippine government.

- ^ Osmena became the sole President of the Philippines upon Laurel's dissolution of the Second Philippine Republic. The Commonwealth government became the sole governing entity of the Philippines.

References[]

- ^ G.R. No. L-7037, March 15, 1912

- ^ American Colonial Careerist, p. 104

- ^ Company, Fookien Times Publishing (1986). The Fookien Times Philippines Yearbook. Fookien Times. p. 226. ISBN 9789710503506.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Justices of the Supreme Court, p. 175

- ^ "G.R. No. L-45081". lawphil.net. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ^ "G.R. No. 47800 December 2, 1940 - MAXIMO CALALANG v. A. D. WILLIAMS". chanrobles.com. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ^ "Official Program Aquino Inaugural (Excerpts)". Archived from the original on February 12, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Proclamation No. 51, s. 1948 | GOVPH". Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ "The execution of Jose Abad Santos | Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines". Officialgazette.gov.ph. 2014-01-21. Retrieved 2019-09-28.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Molina, Antonio. The Philippines: Through the centuries. Manila: University of Sto. Tomas Cooperative, 1961. Prin

- ^ By Sword and By Fire, p. 137

- ^ Joaquin, Nick (1990). Manila, My Manila. Vera-Reyes, Inc.

- ^ Gordon, Andrew (2003). The Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present. Oxford University Press. p. 211. ISBN 0-19-511060-9. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

- ^ "Proclamation No. 29". The Lawphil Project - Philippine Laws and Jurisprudence Databank. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ "Proclamation No. 30". The Lawphil Project - Philippine Laws and Jurisprudence Databank. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ Le président des Iles Philippines Laurel au pape Pie XII. Rome, 11 March 1944. (A.E.S. 1927/44). Acts and Documents of the Holy See Relative to the Second World War Vol. 11 pp. 232-234

- ^ "Philippine History". DLSU-Manila. Archived from the original on August 22, 2006. Retrieved January 27, 2011.

Japan's efforts to win Filipino loyalty found expression in the establishment (Oct. 14, 1943) of a "Philippine Republic", with José P. Laurel, former supreme court justice, as president. But the people suffered greatly from Japanese brutality, and the puppet government gained little support.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Halili, M.c. (2004). Philippine history. Rex Bookstore, Inc. pp. 235–241. ISBN 978-971-23-3934-9. Retrieved January 27, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ocampo, Ambeth (2000) [1995]. "The Irony of Tragedy". Bonifacio's Bolo (4th ed.). Pasig: Anvil Publishing. p. 60. ISBN 971-27-0418-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Ocampo, Ambeth (2000) [1995]. "The Irony of Tragedy". Bonifacio's Bolo (4th ed.). Pasig: Anvil Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 971-27-0418-1.

- ^ Molina, Antonio. The Philippines: Through the centuries. Manila: University of Santo Tomas Cooperative, 1961. Print.

- ^ "Elpidio Quirino". Retrieved 2009-08-09.

- ^ Lirio, Gerry (July 13, 2008). "Villars take over storied Laurel house on Shaw Blvd". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on February 9, 2009. Retrieved March 22, 2009.

- ^ Justices of the Supreme Court, p. 176

- ^ Register of the Jose P. Laurel Papers

- ^ Mariano Antonio Laurel's Birth Register

- ^ Mariano Laurel's Death Certificate

Sources[]

- Laurel, Jose P. (1953). Bread and Freedom.

- Zaide, Gregorio F. (1984). Philippine History and Government. National Bookstore Printing Press.

- Sevilla, Victor J. (1985). Justices of the Supreme Court of the Philippines Vol. I. Quezon City, Philippines: New Day Publishers. pp. 79–80, 174–176. ISBN 971-10-0134-9.

- Malcolm, George A. (1957). American Colonial Careerist. United States of America: Christopher Publishing House. pp. 103–104, 96–97, 139, 249–251.

- Aluit, Alfonso (1994). By Sword and Fire: The Destruction of Manila in World War II February 3 – March 3, 1945. Philippines: National Commission for Culture and the Arts. pp. 134–138. ISBN 971-8521-10-0.

- Ocampo, Ambeth (2000) [1995]. "The Irony of Tragedy". Bonifacio's Bolo (4th ed.). Pasig: Anvil Publishing. pp. 60–61. ISBN 971-27-0418-1.

- President Jose P. Laurel

- President of the Philippines José Paciano Laurel's address, Greater East Asia Conference, November 5–6, 1943

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to José P. Laurel. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Works by or about Jose P. Laurel at Internet Archive

- The Jose P. Laurel Memorial Foundation

- The Philippine Presidency Project

- "JOSE LAUREL DIES; FILIPINO LEADER; Head of Wartime Japanese Puppet Regime – Lost Race for President in 1949". New York Times. November 6, 1959. Retrieved January 8, 2008.

| showOffices and distinctions |

|---|

- José P. Laurel

- 1891 births

- 1959 deaths

- Deaths in Metro Manila

- Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the Philippines

- Colegio de San Juan de Letran alumni

- Filipino collaborators with Imperial Japan

- Filipino expatriates in Japan

- Filipino expatriates in the United States

- Filipino lawyers

- Filipino Roman Catholics

- KALIBAPI politicians

- Laurel family

- Lyceum of the Philippines University

- Majority leaders of the Senate of the Philippines

- Nacionalista Party politicians

- People from Tanauan, Batangas

- Candidates in the 1949 Philippine presidential election

- Presidents of the Philippines

- Recipients of Philippine presidential pardons

- Secretaries of Justice of the Philippines

- Secretaries of the Interior and Local Government of the Philippines

- Senators of the 2nd Congress of the Philippines

- Senators of the 3rd Congress of the Philippines

- Senators of the 8th Philippine Legislature

- Senators of the 7th Philippine Legislature

- Shooting survivors

- Tagalog people

- University of the Philippines alumni

- University of the Philippines College of Law alumni

- University of Santo Tomas alumni

- World War II political leaders

- Yale Law School alumni

- Heads of government who were later imprisoned

- 20th-century lawyers