Kansas City, Missouri

Kansas City | |

|---|---|

| City of Kansas City | |

From top to bottom, left to right: Downtown Kansas City from Liberty Memorial, KC Streetcar, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts, and Liberty Memorial | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nickname(s): "KC", "KCMO", the "City of Fountains", "Paris of the Plains", and the "Heart of America" | |

City boundaries and location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 39°05′59″N 94°34′42″W / 39.09972°N 94.57833°WCoordinates: 39°05′59″N 94°34′42″W / 39.09972°N 94.57833°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Counties | Jackson, Clay, Platte, Cass |

| Incorporated | June 1, 1850 (as the Town of Kansas); March 28, 1853 (as the City of Kansas) |

| Named for | Kansas River |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Quinton Lucas (D) |

| • Body | Kansas City, Missouri City Council |

| Area | |

| • City | 318.98 sq mi (826.14 km2) |

| • Land | 314.88 sq mi (815.55 km2) |

| • Water | 4.09 sq mi (10.60 km2) |

| • Urban | 584.4 sq mi (1,513.59 km2) |

| • Metro | 7,952 sq mi (20,596 km2) |

| Elevation | 910 ft (277 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 508,090 |

| • Rank | 36th in the United States 1st in Missouri |

| • Density | 1,613.60/sq mi (623.00/km2) |

| • Metro | 2,192,035 (31st) |

| Demonym(s) | Kansas Citian |

| Time zone | UTC−06:00 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−05:00 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 64101-64102, 64105-64106, 64108-64114, 64116-64121, 64123-64134, 64136-64139, 64141, 64144-64149, 64151-64158, 64161, 64163-64168, 64170-64172, 64179-64180, 64183-64184, 64187-64188, 64190-64193, 64195-64199, 64999[4] |

| Area codes | 816, 975 (planned) |

| FIPS code | 29000-38000[5] |

| GNIS feature ID | 748198[6] |

| Interstates | |

| Airports | Kansas City International Airport, Charles B. Wheeler Downtown Airport |

| Website | kcmo |

Kansas City (abbreviated KC or KCMO) is the largest city in Missouri by population and area. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city had a population of 508,090 in 2020,[2] and was the 36th most-populous city in the United States as of the 2020 census. It is the most populated municipality and historic core city of the Kansas City metropolitan area, which straddles the Kansas–Missouri state line and has a population of 2,192,035.[3] Most of the city lies within Jackson County, but portions spill into Clay, Cass, and Platte counties. Kansas City was founded in the 1830s as a Missouri River port at its confluence with the Kansas River coming in from the west. On June 1, 1850, the town of Kansas was incorporated; shortly after came the establishment of the Kansas Territory. Confusion between the two ensued, and the name Kansas City was assigned to distinguish them soon after.

Sitting on Missouri's western boundary with Kansas, with Downtown near the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers, the city encompasses about 319.03 square miles (826.3 km2), making it the 23rd largest city by total area in the United States. It serves as one of the two county seats of Jackson County, along with major suburb Independence. Other major suburbs include the Missouri cities of Blue Springs and Lee's Summit and the Kansas cities of Overland Park, Olathe, and Kansas City, Kansas.

The city is composed of several neighborhoods, including the River Market District in the north, the 18th and Vine District in the east, and the Country Club Plaza in the south. Celebrated cultural traditions include Kansas City jazz, theater which was the center of the Vaudevillian Orpheum circuit in the 1920s, the Chiefs and Royals sports franchises, and famous cuisine based on Kansas City-style barbecue, Kansas City strip steak, and craft breweries. The city was ranked as a gamma- global city in 2020 by GaWC.

History[]

Kansas City, Missouri, was incorporated as a town on June 1, 1850, and as a city on March 28, 1853. The territory, straddling the border between Missouri and Kansas at the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri rivers, was considered a good place to build settlements.

The Antioch Christian Church, Dr. James Compton House, and Woodneath are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[7]

Exploration and settlement[]

The first documented European visitor to the eventual site of Kansas City was Étienne de Veniard, Sieur de Bourgmont, who was also the first European to explore the lower Missouri River. Criticized for his response to the Native American attack on Fort Détroit, he had deserted his post as fort commander and was avoiding French authorities. Bourgmont lived with a Native American wife in a village about 90 miles (140 km) east near Brunswick, Missouri, where he illegally traded furs.

To clear his name, he wrote Exact Description of Louisiana, of Its Harbors, Lands and Rivers, and Names of the Indian Tribes That Occupy It, and the Commerce and Advantages to Be Derived Therefrom for the Establishment of a Colony in 1713 followed in 1714 by The Route to Be Taken to Ascend the Missouri River. In the documents, he describes the junction of the "Grande Riv[ière] des Cansez" and Missouri River, making him the first to adopt those names. French cartographer Guillaume Delisle used the descriptions to make the area's first reasonably accurate map.

The Spanish took over the region in the Treaty of Paris in 1763, but were not to play a major role other than taxing and licensing Missouri River ship traffic. The French continued their fur trade under Spanish license. The Chouteau family operated under Spanish license at St. Louis, in the lower Missouri Valley as early as 1765 and in 1821 the Chouteaus reached Kansas City, where François Chouteau established Chouteau's Landing.

After the 1804 Louisiana Purchase, Lewis and Clark visited the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri rivers, noting it was a good place to build a fort. In 1831, a group of Mormons from New York settled in what would become the city. They built the first school within Kansas City's current boundaries, but were forced out by mob violence in 1833, and their settlement remained vacant.[8]

In 1831 Gabriel Prudhomme Sr., a Canadian trapper, purchased 257 acres of land fronting the Missouri River. He established a home for his wife, Josephine, and six children. He operated a ferry on the river.[9]

In 1833 John McCoy, son of Baptist missionary Isaac McCoy, established West Port along the Santa Fe Trail, 3 miles (4.8 kilometers) away from the river. In 1834 McCoy established Westport Landing on a bend in the Missouri to serve as a landing point for West Port. He found it more convenient to have his goods offloaded at the Prudhomme landing than in Independence. Several years after Gabriel Prudhomme's death, a group of fourteen investors purchased his land at auction on 14 November 1838. By 1839 the investors divided the property and the first lots were sold in 1846 after legal complications were settled. The remaining lots were sold by February 1850.[9]

In 1850, the landing area was incorporated as the Town of Kansas.[10] By that time, the Town of Kansas, Westport, and nearby Independence, had become critical points in the westward expansion of the United States. Three major trails – the Santa Fe, California, and Oregon – all passed through Jackson County.

On February 22, 1853, the City of Kansas was created with a newly elected mayor. It had an area of 0.70 square miles (1.8 km2) and a population of 2,500. The boundary lines at that time extended from the middle of the Missouri River south to what is now Ninth Street, and from Bluff Street on the west to a point between Holmes Road and Charlotte Street on the east.[11]

American Civil War[]

During the Civil War, the city and its immediate surroundings were the focus of intense military activity. Although the First Battle of Independence in August 1862 resulted in a Confederate States Army victory, the Confederates were unable to leverage their win in any significant fashion, as Kansas City was occupied by Union troops and proved too heavily fortified to assault. The Second Battle of Independence, which occurred on October 21–22, 1864, as part of Sterling Price's Missouri expedition of 1864, also resulted in a Confederate triumph. Once again their victory proved hollow, as Price was decisively defeated in the pivotal Battle of Westport the next day, effectively ending Confederate efforts to regain Missouri.

General Thomas Ewing, in response to a successful raid on nearby Lawrence, Kansas, led by William Quantrill, issued General Order No. 11, forcing the eviction of residents in four western Missouri counties – including Jackson – except those living in the city and nearby communities and those whose allegiance to the Union was certified by Ewing.

Post–Civil War[]

After the Civil War, Kansas City grew rapidly, largely losing its Southern identity. The selection of the city over Leavenworth, Kansas, for the Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad bridge over the Missouri River brought about significant growth. The population exploded after 1869, when the Hannibal Bridge, designed by Octave Chanute, opened. The boom prompted a name change to Kansas City in 1889, and the city limits to be extended south and east. Westport became part of Kansas City on December 2, 1897. In 1900, Kansas City was the 22nd largest city in the country, with a population of 163,752 residents.[12]

Kansas City, guided by landscape architect George Kessler, became a leading example of the City Beautiful movement, offering a network of boulevards and parks.[13] New neighborhoods like Southmoreland and the Rockhill District were conceived to accommodate the city's largest residencies of palatial proportions.

The relocation of Union Station to its current location in 1914 and the opening of the Liberty Memorial in 1923 provided two of the city's most identifiable landmarks. Robert A. Long, president of the Liberty Memorial Association, was a driving force in the funding for construction. Long was a longtime resident and wealthy businessman. He built the R.A. Long Building for the Long-Bell Lumber Company, his home, Corinthian Hall (now the Kansas City Museum) and Longview Farm.

Further spurring Kansas City's growth was the opening of the innovative Country Club Plaza development by J.C. Nichols in 1925, as part of his Country Club District plan.

20th century streetcar system[]

The Kansas City streetcar system once had hundreds of miles of streetcars running through the city and was one of the largest systems in the country.[14] In 1903 the 8th Street Tunnel was built as an underground streetcar system through the city. The last run of the streetcar was on June 23, 1957, but the tunnel still exists.[15]

Pendergast era[]

At the start of the 20th century, political machines gained clout in the city, with the one led by Tom Pendergast dominating the city by 1925. Several important buildings and structures were built during this time, including the Kansas City City Hall and the Jackson County Courthouse. During this time, he aided one of his nephew's friends, Harry S. Truman in a political career. Truman eventually became a senator, then vice-president, then president[16]. The machine fell in 1939 when Pendergast, riddled with health problems, pleaded guilty to tax evasion after long federal investigations. His biographers have summed up Pendergast's uniqueness:

Pendergast may bear comparison to various big-city bosses, but his open alliance with hardened criminals, his cynical subversion of the democratic process, his monarchistic style of living, his increasingly insatiable gambling habit, his grasping for a business empire, and his promotion of Kansas City as a wide-open town with every kind of vice imaginable, combined with his professed compassion for the poor and very real role as city builder, made him bigger than life, difficult to characterize.[17]

Post–World War II[]

Kansas City's suburban development began with a streetcar system in the early decades of the 20th century. The city's first suburbs were in the neighborhoods of Pendleton Heights and Quality Hill. After World War II, many relatively affluent residents left for suburbs in Johnson County, Kansas, and eastern Jackson County, Missouri. Many also went north of the Missouri River, where Kansas City had incorporated areas between the 1940s and 1970s.

Troost dividing wall and white flight[]

Troost Avenue, once the eastern edge of Kansas City, Mo. and a residential corridor nicknamed Millionaire Row, is now widely seen as one of the city's most prominent racial and economic dividing lines due to urban decay, which was caused by white flight.[18][19] During the civil rights era the city blocked people of color from moving to homes west of Troost Avenue, causing the areas east of Troost to have one of the worst murder rates in the country. This led to the dominating economic success of neighboring Johnson County.[20]

In 1950, African Americans represented 12.2% of Kansas City's population.[12] The sprawling characteristics of the city and its environs today mainly took shape after 1960s race riots. The April 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. was a catalyst for the 1968 Kansas City riot. At this time, slums were forming in the inner city, and many who could afford to do so left for the suburbs and outer areas of the city. The post-World War II ideals of suburban life and the "American Dream" also contributed to the sprawl of the area. The city's population continued to grow, but the inner city declined. The city's most populous ethnic group, non-Hispanic whites,[21] declined from 89.5% in 1930 to 54.9% in 2010.[12]

In 1940, the city had about 400,000 residents; by 2000, it was home to only about 440,000. From 1940 to 1960, the city more than doubled its physical size, while increasing its population by only about 75,000. By 1970, the city covered approximately 316 square miles (820 km2), more than five times its size in 1940.

Hyatt Regency walkway collapse[]

The Hyatt Regency walkway collapse was a major disaster that occurred on July 17, 1981, killing 114 people and injuring more than 200 others during a tea dance in the 45-story Hyatt Regency hotel in Crown Center. It is the deadliest structural collapse in US history other than the September 11 attacks.[22] In 2015 a memorial called the Skywalk Memorial Plaza was built for the families of the victims of the disaster, across the street from the hotel which is now a Sheraton.[23]

21st century[]

Downtown Kansas City re-development[]

In the 21st century, the Kansas City area has undergone extensive redevelopment, with more than $6 billion in improvements to the downtown area on the Missouri side. One of the main goals is to attract convention and tourist dollars, office workers, and residents to downtown KCMO. Among the projects include the redevelopment of the Power & Light District, located in the area to the east of the Power & Light Building (the former headquarters of the Kansas City Power & Light Company, which is now based in the district's northern end), into a retail and entertainment district; and the Sprint Center, an 18,500-seat arena that opened in 2007, funded by a 2004 ballot initiative involving a tax on car rentals and hotels, designed to meet the stadium specifications for a possible future NBA or NHL franchise,[24] and was renamed T-Mobile Center in 2020; Kemper Arena, which was replaced by Sprint Center, fell into disrepair and was sold to private developers. By 2018, the arena was being converted to a sports complex under the name Hy-Vee Arena.[25] The Kauffman Performing Arts Center opened in 2011 providing a new, modern home to the KC Orchestra and Ballet. In 2015, an 800-room Hyatt Convention Center Hotel was announced for a site next to the Performance Arts Center & Bartle Hall. Construction was scheduled to start in early 2018 with Loews as the operator.[26]

From 2007 to 2017, downtown residential population in Kansas City quadrupled and continues to grow. The area has grown from almost 4,000 residents in the early 2000s to nearly 30,000 as of 2017. Kansas City's downtown ranks as the 6th-fastest-growing downtown in America with the population expected to grow by more than 40% by 2022. Conversions of office buildings such as the Power & Light Building and the Commerce Bank Tower into residential and hotel space has helped to fulfill the demand. New apartment complexes like One, Two, and Three Lights, River Market West, and 503 Main have begun to reshape Kansas City's skyline. Strong demand has led to occupancy rates in the upper 90%.[27]

While the residential population of downtown has boomed, the office population has dropped significantly from the early 2000s to the mid 2010s. AMC and other top employers moved their operations to modern office buildings in the suburbs. High office vacancy plagued downtown, leading to the neglect of many office buildings. By the mid 2010s, many office buildings were converted to residential uses and the Class A vacancy rate plunged to 12% in 2017. Swiss Re, Virgin Mobile, AutoAlert, and others have begun to move operations to downtown Kansas City from the suburbs as well as expensive coastal cities.[28][29]

Transportation developments[]

The area has seen additional development through various transportation projects, including improvements to the Grandview Triangle, which intersects Interstates 435 and 470, and U.S. Route 71, a thoroughfare long notorious for fatal accidents.

In July 2005, the Kansas City Area Transportation Authority (KCATA) launched Kansas City's first bus rapid transit line, the Metro Area Express (MAX), which links the River Market, Downtown, Union Station, Crown Center and the Country Club Plaza. The KCATA continues to expand MAX with additional routes on Prospect Avenue, Troost Avenue, and Independence Avenue.[30]

In 2013, construction began on a two-mile streetcar line in downtown Kansas City (funded by a $102 million ballot initiative that was passed in 2012) that runs between the River Market and Union Station, it began operation in May 2016. In 2017, voters approved the formation of a TDD to expand the streetcar line south 3.5 miles from Union Station to UMKC's Volker Campus. Additionally in 2017, the KC Port Authority began engineering studies for a Port Authority funded streetcar expansion north to Berkley Riverfront Park. Citywide, voter support for rail projects continues to grow with numerous light rail projects in the works.[31][32]

In 2016, Jackson County, Missouri, acquired unused rail lines as part of a long-term commuter rail plan. For the time being, the line is being converted to a trail while county officials negotiate with railroads for access to tracks in Downtown Kansas City.

On November 7, 2017, Kansas City, Missouri, voters overwhelmingly approved a new single terminal at Kansas City International Airport by a 75% to 25% margin. The new single terminal will replace the three existing "Clover Leafs" at KCI Airport and is expected to open in October 2022.[33]

Geography[]

The city has an area of 319.03 square miles (826.28 km2), of which, 314.95 square miles (815.72 km2) is land and 4.08 square miles (10.57 km2) is water.[34] Bluffs overlook the rivers and river bottom areas. Kansas City proper is bowl-shaped and is surrounded to the north and south by glacier-carved limestone and bedrock cliffs. Kansas City is at the confluence between the and Minnesota ice lobes during the maximum late Independence glaciation of the Pleistocene epoch. The Kansas and Missouri rivers cut wide valleys into the terrain when the glaciers melted and drained. A partially filled spillway valley crosses the central city. This valley is an eastward continuation of the Turkey Creek Valley. It is the closest major city to the geographic center of the contiguous United States, or "Lower 48".

Cityscape[]

Kansas City, Missouri, comprises more than 240[35] neighborhoods, some with histories as independent cities or as the sites of major events.

Architecture[]

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art opened its Euro-Style Bloch addition in 2007, and the Safdie-designed Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts opened in 2011. The Power and Light Building is influenced by the Art Deco style and sports a glowing sky beacon. The new world headquarters of H&R Block is a 20-story all-glass oval bathed in a soft green light. The four industrial artworks atop the support towers of the Kansas City Convention Center (Bartle Hall) were once the subject of ridicule, but now define the night skyline near the T-Mobile Center along with One Kansas City Place (Missouri's tallest office tower), the KCTV-Tower (Missouri's tallest freestanding structure) and the Liberty Memorial, a World War I memorial and museum that flaunts simulated flames and smoke billowing into the night skyline. It was designated as the National World War I Museum and Memorial in 2004 by the United States Congress. Kansas City is home to significant national and international architecture firms including ACI Boland, BNIM, 360 Architecture, HNTB, Populous. Frank Lloyd Wright designed two private residences and Community Christian Church there.

Kansas City hosts more than 200 working fountains, especially on the Country Club Plaza. Designs range from French-inspired traditional to modern. Highlights include the Black Marble H&R Block fountain in front of Union Station, which features synchronized water jets; the Nichols Bronze Horses at the corner of Main and J.C. Nichols Parkway at the entrance to the Plaza Shopping District; and the fountain at Hallmark Cards World Headquarters in Crown Center.

City Market[]

Since its inception in 1857, City Market has been one of the largest and most enduring public farmers' markets in the American Midwest, linking growers and small businesses to the community. More than 30 full-time merchants operate year-round and offer specialty foods, fresh meats and seafood, restaurants and cafes, floral, home accessories and more.[36] The City Market is also home to the Arabia Steamboat Museum, which houses artifacts from a steamboat that sank near Kansas City in 1856.[36]

Downtown[]

Downtown Kansas City is an area of 2.9 square miles (7.5 km2) bounded by the Missouri River to the north, 31st Street to the south, Troost Avenue to the East, and State Line Road to the west. Areas near Downtown Kansas City include the 39th Street District, which is known as Restaurant Row,[37] and features one of Kansas City's largest selections of independently owned restaurants and boutique shops. It is a center of literary and visual arts, and bohemian culture. Crown Center is the headquarters of Hallmark Cards and a major downtown shopping and entertainment complex. It is connected to Union Station by a series of covered walkways. The Country Club Plaza, or simply "the Plaza", is an upscale, outdoor shopping and entertainment district. It was the first suburban shopping district in the United States,[38] designed to accommodate shoppers arriving by automobile,[39] and is surrounded by apartments and condominiums, including a number of high rise buildings. The associated Country Club District to the south includes the Sunset Hill and Brookside neighborhoods, and is traversed by Ward Parkway, a landscaped boulevard known for its statuary, fountains and large, historic homes. Kansas City's Union Station is home to Science City, restaurants, shopping, theaters, and the city's Amtrak facility.

After years of neglect and seas of parking lots, Downtown Kansas City is undergoing a period of change with over $6 billion in development since 2000. Many residential properties recently have been or are under redevelopment in three surrounding warehouse loft districts and the Central Business District. The Power & Light District, a new, nine-block entertainment district comprising numerous restaurants, bars, and retail shops, was developed by the Cordish Company of Baltimore, Maryland. Its first tenant opened on November 9, 2007. It is anchored by the T-Mobile Center, a 19,000-seat sports and entertainment complex.[40]

Climate[]

| Kansas City | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Kansas City lies in the Midwestern United States, near the geographic center of the country, at the confluence of the Missouri and Kansas rivers. The city lies in the northern periphery of the humid subtropical zone,[41] but is interchangeable with the humid continental climate due to roughly 104 air frosts on average per annum.[42] The city is part of USDA plant hardiness zones 5b and 6a.[43] In the center of North America, far removed from a significant body of water, there is significant potential for extreme hot and cold swings throughout the year. The warmest month is July, with a 24-hour average temperature of 81.0 °F (27.2 °C). The summer months are hot and humid, with moist air riding up from the Gulf of Mexico, and high temperatures surpass 100 °F (38 °C) on 5.6 days of the year, and 90 °F (32 °C) on 47 days.[44][45] The coldest month of the year is January, with an average temperature of 31.0 °F (−0.6 °C). Winters are cold, with 22 days where the high temperature is at or below 32 °F (0 °C) and 2.5 nights with a low at or below 0 °F (−18 °C).[44] The official record highest temperature is 113 °F (45 °C), set on August 14, 1936, at Downtown Airport, while the official record lowest is −23 °F (−31 °C), set on December 22 and 23, 1989.[44] Normal seasonal snowfall is 13.4 inches (34 cm) at Downtown Airport and 18.8 in (48 cm) at Kansas City International Airport. The average window for freezing temperatures is October 31 to April 4, while for measurable (0.1 in or 0.25 cm) snowfall, it is November 27 to March 16 as measured at Kansas City International Airport.[44] Precipitation, both in frequency and total accumulation, shows a marked uptick in late spring and summer.

Kansas City is located in "Tornado Alley", a broad region where cold air from Canada collides with warm air from the Gulf of Mexico, leading to the formation of powerful storms, especially during the spring. The Kansas City metropolitan area has experienced several significant outbreaks of tornadoes in the past, including the Ruskin Heights tornado in 1957[46] and the May 2003 tornado outbreak sequence. The region can also experience ice storms during the winter months, such as the 2002 ice storm during which hundreds of thousands of residents lost power for days and (in some cases) weeks.[47] Kansas City and its outlying areas are also subject to flooding, including the Great Floods of 1951 and 1993.

| showClimate data for Kansas City, Missouri (Downtown Airport), 1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1934–present) |

|---|

| showClimate data for Kansas City, Missouri |

|---|

Demographics[]

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 4,418 | — | |

| 1870 | 32,260 | 630.2% | |

| 1880 | 55,785 | 72.9% | |

| 1890 | 132,716 | 137.9% | |

| 1900 | 163,752 | 23.4% | |

| 1910 | 248,381 | 51.7% | |

| 1920 | 324,410 | 30.6% | |

| 1930 | 399,746 | 23.2% | |

| 1940 | 400,178 | 0.1% | |

| 1950 | 456,622 | 14.1% | |

| 1960 | 475,539 | 4.1% | |

| 1970 | 507,087 | 6.6% | |

| 1980 | 448,159 | −11.6% | |

| 1990 | 435,146 | −2.9% | |

| 2000 | 441,545 | 1.5% | |

| 2010 | 459,787 | 4.1% | |

| 2020 | 508,090 | 10.5% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[54] 2010–2020[2] | |||

According to the 2010 census, the racial composition of Kansas City was as follows:

- White: 59.2% (non-Hispanic white: 54.9%)

- Black or African American: 29.9%

- Hispanic or Latino (of any race): 10.0%

- Some other race: 4.5%

- Two or more races: 3.2%

- Asian: 2.5%

- Native American: 0.5%

- Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander: 0.2%

Kansas City has the second largest Somali and Sudanese populations in the United States. The Latino/Hispanic population of Kansas City, which is heavily Mexican and Central American, is spread throughout the metropolitan area, with some concentration in the northeast part of the city and southwest of downtown. The Asian population, mostly Southeast Asian, is partly concentrated within the northeast side to the Columbus Park neighborhood in the Greater Downtown area, a historically Italian American neighborhood, the UMKC area and in River Market, in northern Kansas City.[55][56][57]

The Historic Kansas City boundary is roughly 58 square miles (150 km2) and has a population density of about 5,000 people per sq. mi. It runs from the Missouri River to the north, 79th Street to the south, the Blue River to the east, and State Line Road to the west. During the 1960s and 1970s, Kansas City annexed large amounts of land, which are largely undeveloped to this day.

Between the 2000 and 2010 Census counts, the urban core of Kansas City continued to drop significantly in population. The areas of Greater Downtown in the center city, and sections near I-435 and I-470 in the south, and Highway 152 in the north are the only areas of Kansas City, Missouri, to have seen an increase in population, with the Northland seeing the greatest population growth.[58] Even so, the population of Kansas City as a whole from 2000 to 2010 increased by 4.1%.

| hideRacial composition | 2010[21] | 1990[12] | 1970[12] | 1940[12] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 59.2% | 66.8% | 77.2% | 89.5% |

| —Non-Hispanic white | 54.9% | 65.0% | 75.0%[59] | N/A |

| Black or African American | 29.9% | 29.6% | 22.1% | 10.4% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 10.0% | 3.9% | 2.7%[59] | N/A |

Economy[]

While it was once true that much of the economic development in the Kansas City metro area was on the Kansas side, as of May, 2021, the Missouri portion is leading in total non-farm employment. This reflects a more balanced new economic picture. [60] The federal government is the largest employer in the Kansas City metro area. More than 146 federal agencies maintain a presence there. Kansas City is one of ten regional office cities for the US government.[61] The Internal Revenue Service maintains a large service center in Kansas City that occupies nearly 1.4 million square feet (130,000 m2).[62] It is one of only two sites to process paper returns.[63] The IRS has approximately 2,700 full-time employees in Kansas City, growing to 4,000 during tax season. The General Services Administration has more than 800 employees. Most are at the Bannister Federal Complex in South Kansas City. The Bannister Complex was also home to the Kansas City Plant, which is a National Nuclear Security Administration facility operated by Honeywell. The Kansas City Plant has since been moved to a new location on Botts Road. Honeywell employs nearly 2,700 at the Kansas City Plant, which produces and assembles 85% of the non-nuclear components of the United States nuclear bomb arsenal.[64] The Social Security Administration has more than 1,700 employees in the Kansas City area, with more than 1,200 at its downtown Mid-America Program Service Center (MAMPSC).[65] The United States Postal Service operates post offices in Kansas City. The Kansas City Main Post Office is at 300 West Pershing Road.[66]

In 2019, the US Department of Agriculture relocated two federal research labs, ERS and NIFA, to the metro area. This move was considered controversial at the time of announcement, and resulted in multiple people leaving the agencies. The new location for these agencies will be in the downtown area.

Ford Motor Company operates a large manufacturing facility in Claycomo at the Ford Kansas City Assembly Plant, which builds the Ford F-150. The General Motors Fairfax Assembly Plant is in adjacent Kansas City, Kansas. Now shuttered Smith Electric Vehicles built electric vehicles in the former TWA/American Airlines overhaul facility at Kansas City International Airport until 2017.

One of the largest US drug manufacturing plants is the Sanofi-Aventis plant in south Kansas City on a campus developed by Ewing Kauffman's Marion Laboratories.[67] Of late, it has been developing academic and economic institutions related to animal health sciences, an effort most recently bolstered by the selection of Manhattan, Kansas, at one end of the[68] Kansas City Animal Health Corridor, as the site for the National Bio and Agro-Defense Facility, which researches animal diseases. Additionally, the Stowers Institute for Medical Research engages in medical basic science research. They offer educational opportunities for both predoctoral and postdoctoral candidates and work with Open University and University of Kansas Medical Center in a joint Interdisciplinary Graduate Program in Biomedical Science (IGPBS).

Numerous agriculture companies operate out of the city. Dairy Farmers of America, the largest dairy co-op in the United States is located in northern Kansas City. The National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics and The National Association of Basketball Coaches are based in Kansas City.

The business community is serviced by two major business magazines, the Kansas City Business Journal (published weekly) and Ingram's Magazine (published monthly), as well as other publications, including a local society journal, the Independent (published weekly).

The Kansas City Federal Reserve Bank built a new building that opened in 2008 near Union Station. Missouri is the only state to have two of the 12 Federal Reserve Bank headquarters (the second is in St. Louis). Kansas City's effort to get the bank was helped by former mayor James A. Reed, who as senator, broke a tie to pass the Federal Reserve Act.[69]

The national headquarters for the Veterans of Foreign Wars is headquartered just south of Downtown.

With a Gross Metropolitan Product of $41.68 billion in 2004, Kansas City's (Missouri side only) economy makes up 20.5% of Missouri's gross state product.[70] In 2014, Kansas City was ranked #6 for real estate investment.[71]

Three international law firms, Lathrop & Gage, Stinson Leonard Street, and Shook, Hardy & Bacon are based in the city.

Headquarters[]

The following companies are headquartered in Kansas City, Missouri:

- American Century Investments

- Andrews McMeel Universal

- Applebee's (former)

- Barkley Inc.

- Bernstein-Rein

- Black & Veatch's Global Water Business

- Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas City

- BNIM

- Boulevard Brewing Company

- Cerner

- Children International

- Commerce Bancshares

- Copaken, White & Blitt

- Evergy, formerly Great Plains Energy

- Freightquote.com

- Garney Holding Company

- Hallmark Cards

- H&R Block

- HNTB

- Hostess Brands

- J.E. Dunn Construction Group

- Kansas City Southern Railway

- Lockton Companies

- MANICA Architecture

- Novastar Financial

- Populous

- Russell Stover Candies

- Smith Electric Vehicles

- UMB Financial Corporation

- Veterans of Foreign Wars

- Walton Construction

Top employers[]

According to the city's Fiscal Year 2014–15 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[72] the top ten principal employers are as follows:

| Rank | Employer | Employees | Percentage of Total Employment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Public School System | 30,172 | 2.92% |

| 2. | Federal Government | 30,000 | 2.91% |

| 3. | State/County/City Government | 24,616 | 2.39% |

| 4. | Cerner Corporation | 10,128 | 0.98% |

| 5. | HCA Midwest Health System | 9,753 | 0.94% |

| 6. | Saint Luke's Health System | 7,550 | 0.73% |

| 7. | Children's Mercy Hospitals and Clinics | 6,305 | 0.61% |

| 8. | T-Mobile | 6,300 | 0.61% |

| 9. | The University of Kansas Hospital | 6,030 | 0.58% |

| 10. | Hallmark Cards, Inc. | 4,600 | 0.45% |

Culture[]

Abbreviations and nicknames[]

Kansas City, Missouri is abbreviated as KCMO and the metropolitan area as KC. Residents are known as Kansas Citians. Kansas City, Missouri is officially nicknamed the "City of Fountains". The fountains at Kauffman Stadium, commissioned by original Kansas City Royals owner Ewing Kauffman, are the largest privately funded fountains in the world.[73] In 2018, UNESCO designated Kansas City as a City of Music.[74] The city has more boulevards than any other city except Paris and has been called "Paris of the Plains". Soccer's popularity, at both professional and youth levels, as well as Children's Mercy Park's popularity as a home stadium for the U.S. Men's National Team led to the appellation "Soccer Capital of America". The city is called the "Heart of America", as it is near both the population center of the United States and the geographic center of the 48 contiguous states.

Performing arts[]

There were only two theaters in Kansas City when , originally from rural Pennsylvania, moved to Kansas City in 1886. Latchaw maintained friendly relations with a number of actors such as Otis Skinner, Richard Mansfield, Maude Adams, Margaret Anglin, John Drew, Minnie Maddern Fiske, Julia Marlowe, E. H. Sothern, and Robert Mantell.[75]

Theater troupes in the 1870s toured the state performing in cities or small towns springing up along the railroad lines. Rail transport had made touring easy allowing theater troupes to travel with costumes, props and sets. As theater grew in popularity after the mid-1880s that number increased and by 1912 ten new theaters had been built in Kansas City.[75]

By the 1920s Kansas City was the center of the vaudevillian Orpheum circuit.[75]

The Kansas City Repertory Theatre is the metropolitan area's top professional theatre company. The Starlight Theatre is an 8,105-seat outdoor theatre designed by Edward Delk. The Kansas City Symphony was founded by R. Crosby Kemper Jr. in 1982 to replace the defunct Kansas City Philharmonic, which was founded in 1933. The symphony performs at the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts. Michael Stern is the symphony's music director and lead conductor. Lyric Opera of Kansas City, founded in 1958, performs at the Kauffman Center, offers one American contemporary opera production during its season, consisting of either four or five productions. The Civic Opera Theater of Kansas City performs at the downtown Folly Theater and at the UMKC Performing Arts Center. Every summer from mid-June to early July, The Heart of America Shakespeare Festival performs at Southmoreland Park near the Nelson-Atkins Museum; the festival was founded by Marilyn Strauss in 1993.

The Kansas City Ballet, founded in 1957 by Tatiana Dokoudovska, is a ballet troupe comprising 25 professional dancers and apprentices. Between 1986 and 2000, it combined with Dance St. Louis to form the State Ballet of Missouri, although it remained in Kansas City. From 1980 to 1995, the Ballet was run by dancer and choreographer Todd Bolender. Today, the Ballet offers an annual repertory split into three seasons, performing classical to contemporary ballets.[76] The Ballet also performs at the Kauffman Center. Kansas City is home to The Kansas City Chorale, a professional 24-voice chorus conducted by Charles Bruffy. The chorus performs an annual concert series and a concert in Phoenix each year with their sister choir, the Phoenix Chorale. The Chorale has made nine recordings (three with the Phoenix Chorale).[77]

Jazz[]

Kansas City jazz in the 1930s marked the transition from big bands to the bebop influence of the 1940s. The 1979 documentary The Last of the Blue Devils portrays this era in interviews and performances by local jazz notables. In the 1970s, Kansas City attempted to resurrect the glory of the jazz era in a family-friendly atmosphere. In the 1970s, an effort to open jazz clubs in the River Quay area of City Market along the Missouri ended in a gang war. Three of the new clubs were blown up in what ultimately ended Kansas City mob influence in Las Vegas casinos. The annual "Kansas City Blues and Jazz Festival" attracts top jazz stars and large out-of-town audiences. It was rated Kansas City's "best festival." by Pitch.com.[78]

Live music venues are found throughout the city, with the highest concentration in the Westport entertainment district centered on Broadway and Westport Road near the Country Club Plaza, as well as the 18th and Vine area's flourish for jazz music. A variety of music genres can be heard or have originated there, including musicians Janelle Monáe, Puddle of Mudd, Isaac James, The Get Up Kids, Shiner, Flee The Seen, The Life and Times, Reggie and the Full Effect, Coalesce, The Casket Lottery, The Gadjits, The Rainmakers, Vedera, The Elders, Blackpool Lights, The Republic Tigers, Tech N9ne, Krizz Kaliko, Kutt Calhoun, Skatterman & Snug Brim, Mac Lethal, Ces Cru, and Solè. As of 2003, the Kansas City Jazz Orchestra, a big band jazz orchestra, performs in the metropolitan area.

In 2018, UNESCO named Kansas City as a "City of Music", making it the only city in the United States with that distinction. The city's funding of $7 million for improvements to the 18th and Vine Jazz District in 2016, coupled with the city's rich musical heritage, contributed to the designation.[74]

Irish culture[]

The large community of Irish-Americans numbers over 50,000.[79] The Irish were the first large immigrant group to settle in Kansas City and founded its first newspaper.[80] The Irish community includes bands, dancers, Irish stores, newspapers and the Kansas City Irish Center at Drexel Hall in Midtown. The first book that detailed the history of the Irish in Kansas City was Missouri Irish: Irish Settlers on the American Frontier, published in 1984. The Kansas City Irish Fest is held over Labor Day weekend every year in Crown Center and Washington Park.

Casinos[]

Missouri voters approved riverboat casino gaming on the Missouri and Mississippi Rivers by referendum with a 63% majority on November 3, 1992. The first casino facility in the state opened in September 1994 in North Kansas City by Harrah's Entertainment (now Caesar's Entertainment).[81] The combined revenues for four casinos exceeded $153 million per month in May 2008.[82] The metropolitan area is home to six casinos: Ameristar Kansas City, Argosy Kansas City, Harrah's North Kansas City, Isle of Capri Kansas City, the 7th Street Casino (which opened in Kansas City, Kansas, in 2008) and Hollywood Casino (which opened in February 2012 in Kansas City, Kansas).

Cuisine[]

Kansas City is famous for its steak and Kansas City-style barbecue, along with the typical array of Southern cuisine. During the heyday of the Kansas City Stockyards, the city was known for its Kansas City steaks or Kansas City strip steaks. The most famous of its steakhouses is the Golden Ox in the Kansas City Live Stock Exchange in the West Bottoms stockyards. These stockyards were second only to those of Chicago in size, but they never recovered from the Great Flood of 1951 and eventually closed. Founded in 1938, Jess & Jim's Steakhouse in the Martin City neighborhood was also well known.

The Kansas City Strip cut of steak is similar to the New York Strip cut, and is sometimes referred to just as a strip steak. Along with Texas, Memphis, North, and South Carolina, Kansas City is lauded as a "world capital of barbecue". More than 90 barbecue restaurants[83] operate in the metropolitan area. The American Royal each fall hosts what it claims is the world's biggest barbecue contest.

Classic Kansas City-style barbecue was an inner-city phenomenon that evolved from the pit of Henry Perry, a migrant from Memphis who is generally credited with opening the city's first barbecue stand in 1921, and blossomed in the 18th and Vine neighborhood. Arthur Bryant's took over the Perry restaurant and added sugar to his sauce to sweeten the recipe a bit. In 1946 one of Perry's cooks, George W. Gates, opened Gates Bar-B-Q, later Gates and Sons Bar-B-Q when his son Ollie joined the family business. Bryant's and Gates are the two definitive Kansas City barbecue restaurants; native Kansas Citian and essayist Calvin Trillin famously called Bryant's "the single best restaurant in the world" in an essay he wrote for Playboy magazine in the 1960s. Fiorella's Jack Stack Barbecue is also well regarded. In 1977, Rich Davis, a psychiatrist, test-marketed his own concoction called K.C. Soul Style Barbecue Sauce. He renamed it KC Masterpiece, and in 1986, he sold the recipe to the Kingsford division of Clorox. Davis retained rights to operate restaurants using the name and sauce, whose recipe popularized the use of molasses as a sweetener in Kansas City-style barbecue sauces.[citation needed]

Kansas City has several James Beard Award-winning/nominated chefs and restaurants. Winning chefs include Michael Smith, Celina Tio, Colby Garrelts, Debbie Gold, Jonathan Justus and Martin Heuser. A majority of the Beard Award-winning restaurants are in the Crossroads district, downtown and in Westport.

Points of interest[]

| Name | Description | Photo |

|---|---|---|

| Country Club Plaza District | A district developed in 1922 featuring Spanish-styled architecture and upscale shops and restaurants. Two universities have locations near the district (University of Missouri-Kansas City and the Kansas City Art Institute). The Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art are around the district as well. |

|

| 18th & Vine District | Cradle of distinctive Kansas City styled jazz. Home of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum, American Jazz Museum, and the future home of the MLB Urban Youth Academy. The district contains several jazz clubs and venues, such as the Gem Theater and the Blue Room Archived May 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. There are talks of the city diverting $27 million to the district to connect the district to the rest of downtown.[84] |

|

| Crossroads Arts District | Home to several restaurants, art galleries, and hotels. First Friday is a popular monthly event in the district. Pop-up galleries, food trucks, venue deals, and music events are planned for First Fridays. Union Station and the Kauffman Center are within the district. Union Station also has exhibits that change frequently, as well as Science City within the building. |

|

| Westport District | Originally a separate town before being annexed by Kansas City, the district contains several restaurants, shops, and nightlife options. Along with the Power and Light District, it serves as one of the city's main entertainment areas. The University of Kansas Hospital is close to the district, just across State Line Road. |

|

| Power and Light District | A new shopping and entertainment district within the Central Business District. It was developed by the Cordish Companies; several apartment towers are being constructed by the company as well. The T-Mobile Center is within the district and is a major anchor development for the area. The Midland Theater, a popular concert venue, is also in the district. |

|

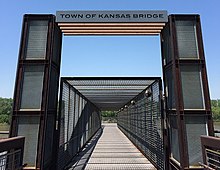

| River Market District/ Berkley Riverfront Park | Kansas City's original neighborhood on the Missouri River. The district contains one of the country's largest and longest lasting public farmers' markets in the nation. There are several unique shops and restaurants throughout the area. Steamboat Arabia Museum is right next to the City Market. Residents and visitors traveling by foot or bike can take the Town of Kansas Bridge connection to get to the Riverfront Heritage Trail which leads to Berkley Riverfront Park, which is operated by Port KC. |

|

| Crown Center | A district developed by Hallmark. The district is a short walk from Liberty Memorial (which features a World War One museum). Archived June 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine |

|

| The West Bottoms | The West Bottoms used to be used primarily as stockyards and for industrial uses, but today the district is slowly being revitalized through the development and redevelopment of apartments and shops. The district is home to the soon-to-be repurposed Kemper Arena, which regularly hosted the American Royal. The arena hosted the 1976 Republican National Convention. |

|

| Several attractions are north of the Missouri River. Zona Rosa is a mixed-used development with shopping, dining, and events. The Charles B. Wheeler Downtown Airport features the Aviation History Museum. Worlds of Fun and Oceans of Fun are major amusement parks of the midwest. |

| |

| Swope Park | Swope Park has an area of 1,805 acres, a larger total space than Central Park, with several attractions. The Kansas City Zoo, encompassing 200 acres, features more than 1,000 animals and was ranked as one of the top 60 zoos in the United States. Starlight Theatre is the second largest outdoor musical theatre venue in the U.S.[85] Sporting Kansas City practice at the soccer complex. |

|

Religion[]

The proportion of Kansas City area residents with a known religious affiliation is 50.75%. The most common religious denominations in the area are:[86]

- None/No affiliation 49.25%

- Catholic 13.2%

- Baptists 10.4%

- Other Christian 10.3%

- Methodist 6.0%

- Pentecostal 2.7%

- Latter-day Saint 2.5%

- Lutheran 2.3%

- Presbyterian 1.7%

- Judaism 0.4%

- Eastern religions 0.4%

- Islam 0.4%

Walt Disney[]

In 1911, Elias Disney moved his family from Marceline to Kansas City. They lived in a new home at 3028 Bellefontaine with a garage he built, in which Walt Disney made his first animation.[87] In 1919, Walt returned from France where he had served as a Red Cross Ambulance Driver in World War I. He started the first animation company in Kansas City, Laugh-O-Gram Studio, in which he designed the character Mickey Mouse. When the company went bankrupt, Walt Disney moved to Hollywood and started The Walt Disney Company on October 16, 1923.

Sports[]

Professional sports teams in Kansas City include the Kansas City Chiefs in the National Football League (NFL), the Kansas City Royals in Major League Baseball (MLB) and Sporting Kansas City in Major League Soccer (MLS).

The following table lists the professional teams in the Kansas City metropolitan area:

| Club | Sport | Founded | League | Venue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kansas City Chiefs | Football | 1960 (as the Dallas Texans) 1963 (as Kansas City Chiefs) |

National Football League | Arrowhead Stadium |

| Kansas City Royals | Baseball | 1969 | Major League Baseball | Kauffman Stadium |

| Sporting Kansas City | Soccer | 1996 | Major League Soccer | Children's Mercy Park (Kansas City, Kansas) |

| Sporting Kansas City II | Soccer | 2016 | USL Championship | Children's Mercy Park (Kansas City, Kansas) |

| Kansas City Mavericks | Hockey | 2009 | ECHL | Cable Dahmer Arena (Independence) |

| Kansas City Comets | Soccer, Indoor | 2010 | Major Arena Soccer League | Cable Dahmer Arena (Independence) |

| Kansas City Blues | Rugby Union | 1966 | USA Rugby Division 1 | Swope Park Training Complex |

| Kansas City Storm | Football, Women's | 2004 | WTFA | North Kansas City High School |

Professional football[]

The Chiefs, now a member of the NFL's American Football Conference, started play in 1960 as the Dallas Texans of the American Football League before moving to Kansas City in 1963. The Chiefs lost Super Bowl I to the Green Bay Packers by a score of 35–10. They came back in 1969 to become the last AFL champion and win Super Bowl IV against the NFL champion Minnesota Vikings by a score of 23–7. In 2020, after 50 years, they won Super Bowl LIV with the score of 31–20 against the San Francisco 49ers.[88] In 2021, they lost Super Bowl LV to the Tampa Bay Buccaneers by a score of 31–9.

Professional baseball[]

The Athletics baseball franchise played in the city from 1955, after moving from Philadelphia, to 1967, when the team relocated to Oakland, California. The city's Major League Baseball franchise, the Royals, started play in 1969, and are the only major league sports franchise in Kansas City that has not relocated or changed its name. The Royals were the first American League expansion team to reach the playoffs, in 1976, to reach the World Series in 1980, and to win the World Series in 1985. The Royals returned to the World Series in 2014 and won in 2015. The Kansas City Royals have 1 Kansas City based player in the MLB Baseball Hall Of Fame, George Brett.

The Kansas City Monarchs, formerly the Kansas City T-Bones, playing in the independent Northern League from 2003 until 2010, and currently in the independent American Association since 2011, and unaffiliated minor league team. They play their games at Legends Field (Kansas City) in Kansas City, Kansas.

Professional soccer[]

The Kansas City Wiz became a charter member of Major League Soccer in 1996. It was renamed the Kansas City Wizards in 1997. In 2011, the team was renamed Sporting Kansas City and moved to its new stadium Children's Mercy Park in Kansas City, Kansas. Sporting's reserve team, Sporting Kansas City II, plays at Shawnee Mission District Stadium in Overland Park, Kansas. FC Kansas City began play in 2013 as an expansion team of the National Women's Soccer League; the team's home games are held at Swope Soccer Village.

College athletics[]

In college athletics, Kansas City has been the home of the Big 12 College Basketball Tournaments. The men's tournament has been played at T-Mobile Center since March 2008. The women's tournament is played at Municipal Auditorium.

The city has one NCAA Division I program, the Kansas City Roos, representing the University of Missouri–Kansas City (UMKC). The program, historically known as the UMKC Kangaroos, adopted its current branding after the 2018–19 school year.

In addition to serving as the home stadium of the Chiefs, Arrowhead Stadium serves as the venue for various intercollegiate football games. It has hosted the Big 12 Championship Game five times. On the last weekend in October, the MIAA Fall Classic rivalry game between Northwest Missouri State University and Pittsburg State University took place at the stadium.

Professional rugby[]

Kansas City is represented on the rugby pitch by the Kansas City Blues RFC, a former member of the Rugby Super League and a Division 1 club. The team works closely with Sporting Kansas City and splits home-games between Sporting's training pitch and Rockhurst University's stadium.

Former teams[]

Kansas City briefly had four short-term major league baseball teams between 1884 and 1915: the Kansas City Unions of the short-lived Union Association in 1884, the Kansas City Cowboys in the National League in 1886, a team of the same name in the then-major league American Association in 1888 and 1889, and the Kansas City Packers in the Federal League in 1914 and 1915. The Kansas City Monarchs of the now-defunct Negro National and Negro American Leagues represented Kansas City from 1920 through 1955. The city also had a number of minor league baseball teams between 1885 and 1955. After the Kansas City Cowboys began play in the 1885 Western League, from 1903 through 1954, the Kansas City Blues played in the high-level American Association minor league. In 1955, Kansas City became a major league city when the Philadelphia Athletics baseball franchise relocated to the city in 1955. Following the 1967 season, the team relocated to Oakland, California.

Kansas City was represented in the National Basketball Association by the Kansas City Kings (called the Kansas City-Omaha Kings from 1972 to 1975), when the former Cincinnati Royals moved to the Midwest. The team left for Sacramento in 1985.

In 1974, the National Hockey League placed an expansion team in Kansas City called the Kansas City Scouts. The team moved to Denver in 1976, then to New Jersey in 1982 where they have remained ever since as the New Jersey Devils.

Parks and boulevards[]

Kansas City has 132 miles (212 km) of boulevards and parkways, 214 urban parks, 49 ornamental fountains, 152 ball diamonds, 10 community centers, 105 tennis courts, 5 golf courses, 5 museums and attractions, 30 pools, and 47 park shelters.[89][90] These amenities are found across the city. Much of the system, designed by George E. Kessler, was constructed from 1893 to 1915.

Cliff Drive, in Kessler Park on the North Bluffs, is a designated State Scenic Byway. It extends 4.27 miles (6.87 km) from The Paseo and Independence Avenue through Indian Mound on Gladstone Boulevard at Belmont Boulevard, with many historical points and architectural landmarks.

Ward Parkway, on the west side of the city near State Line Road, is lined by many of the city's largest and most elaborate homes.

The Paseo is a major north–south parkway that runs 19 miles (31 km) through the center of the city beginning at Cliff Drive. It was modeled on the Paseo de la Reforma, a fashionable Mexico City boulevard. It has been recently renamed Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and now the city has voted to change it back to the Paseo.[91]

Swope Park is one of the nation's largest city parks, comprising 1,805 acres (3 sq mi), more than twice the size of New York City's Central Park.[92] It features a zoo, a woodland nature and wildlife rescue center, 2 golf courses, 2 lakes, an amphitheatre, a day-camp, and numerous picnic grounds. Hodge Park, in the Northland, covers 1,029 acres (416 ha) (1.61 sq. mi.). This park includes the 80-acre (320,000 m2) Shoal Creek Living History Museum, a village of more than 20 historical buildings dating from 1807 to 1885. , 955 acres (3.86 km2) on the banks of the Missouri River on the north edge of downtown, holds annual Independence Day celebrations and other festivals.

A program went underway to replace many of the fast-growing sweetgum trees with hardwood varieties.[93]

Civil Engineering Landmark[]

In 1974, the Kansas City Park and Boulevard System was recognized by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) as a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark.[94] The nomination noted that this park system was among "...the first to integrate the aesthetics of landscape architecture with the practicality of city planning, stimulating other metropolitan areas to undertake similar projects."[95] The park's plan developed by civil engineer George Kessler included some of the "...first specifications for pavements, gutters, curbs, and walks. Other engineering advances included retaining walls, earth dams, subsurface drains, and an impoundment lake - all part of Kansas City's legacy that has influenced urban planning in cities throughout North America."[95]

Law and government[]

City government[]

Kansas City is home to the largest municipal government in the state of Missouri. The city has a council/manager form of government. The role of city manager has diminished over the years. The non-elective office of city manager was created following excesses during the Pendergast days.

The mayor is the head of the Kansas City City Council, which has 12 members elected from six districts (one member elected by voters in the district and one at-large member elected by voters citywide). The mayor is the presiding member, though he or she only votes in the event of a tie. By charter, Kansas City has a "weak-mayor" system, in which most of the power is formally vested in the city council. However, in practice, the mayor is very influential in drafting and guiding public policy.

Kansas City holds city elections in every fourth odd numbered year. The last citywide election was held in May 2019. The officials took office in August 2019 and will hold the position until 2023.

Pendergast was the most prominent leader during the machine politics days. The most nationally prominent Democrat associated with the machine was Harry S Truman, who became a Senator, Vice President and then President of the United States from 1945 to 1953. Kansas City is the seat of the United States District Court for the Western District of Missouri, one of two federal district courts in Missouri. The United States District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri is in St. Louis. It also is the seat of the Western District of the Missouri Court of Appeals, one of three districts of that court (the Eastern District is in St. Louis and the Southern District is in Springfield).

The Mayor, City Council, and City Manager are listed below:[96][97]

</ref>

| Office | Officeholder |

|---|---|

| Mayor (presides over Council) | Quinton Lucas |

| Councilman, District 1 At-large | Kevin O'Neill |

| Councilwoman, District 1 | Heather Hall |

| Councilwoman, District 2 At-large | Teresa Loar |

| Councilman, District 2 | Dan Fowler |

| Councilman, District 3 At-large | Brandon Ellington |

| Councilwoman, District 3 | Melissa Robinson |

| Councilwoman, District 4 At-large | Katheryn Shields |

| Councilman, District 4 | Eric Bunch |

| Councilman, District 5 At-large | Lee Barnes, Jr. |

| Councilwoman, District 5 | Ryana Parks-Shaw |

| Councilwoman, District 6 At-large | Andrea Bough |

| Councilman, District 6 | Kevin McManus |

| City Manager | Brian Platt |

| Mayor Pro-Tem | Kevin Mcmanus |

National political conventions[]

Kansas City hosted the 1900 Democratic National Convention, the 1928 Republican National Convention and the 1976 Republican National Convention. The urban core of Kansas City consistently votes Democratic in presidential elections; however, on the state and local level Republicans often find success, especially in the Northland and other suburban areas of Kansas City.

Federal representation[]

Kansas City is represented by three members of the United States House of Representatives:

- Missouri's 4th congressional district – the Cass County portion of Kansas City; represented by Vicky Hartzler (Republican)

- Missouri's 5th congressional district – all of Kansas City proper in Jackson County, plus Independence; represented by Emanuel Cleaver (Democrat)

- Missouri's 6th congressional district – all of Kansas City proper north of the Missouri River and plus suburbs in eastern Jackson County beyond Independence; represented by Sam Graves (Republican)

Crime[]

Some of the earliest organized violence in Kansas City erupted during the American Civil War. Shortly after the city's incorporation in 1850, so-called Bleeding Kansas erupted, affecting border ruffians and Jayhawkers. During the war, Union troops burned all occupied dwellings in Jackson County south of Brush Creek and east of Blue Creek to Independence in an attempt to halt raids into Kansas. After the war, the Kansas City Times turned outlaw Jesse James into a folk hero via its coverage. James was born in the Kansas City metro area at Kearney, Missouri, and notoriously robbed the Kansas City Fairgrounds at 12th Street and Campbell Avenue.

In the early 20th century under Pendergast, Kansas City became the country's "most wide open town". While this would give rise to Kansas City Jazz, it also led to the rise of the Kansas City mob (initially under Johnny Lazia), as well as the arrival of organized crime. In the 1970s, the Kansas City mob was involved in a gang war over control of the River Quay entertainment district, in which three buildings were bombed and several gangsters were killed. Police investigations gained after boss Nick Civella was recorded discussing gambling bets on Super Bowl IV (where the Kansas City Chiefs defeated the Minnesota Vikings). The war and investigation led to the end of mob control of the Stardust Casino, which was the basis for the film Casino, though the production minimizes the Kansas City connections.

As of November 2012, Kansas City ranked 18th on the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)'s annual survey of crime rates for cities with populations over 100,000.[98] Much of the city's violent crime occurs on the city's lower income East Side. Revitalizing the downtown and midtown areas has been fairly successful and now these areas have below average violent crime compared to other major downtowns.[99][irrelevant citation] According to a 2007 analysis by The Kansas City Star and the University of Missouri-Kansas City, downtown experienced the largest drop in crime of any neighborhood in the city during the 2000s.[100]

Education[]

Colleges and universities[]

Many universities, colleges, and seminaries are in the Kansas City metropolitan area, including:

- University of Missouri–Kansas City − one of four schools in the University of Missouri System − serving more than 15,000 students

- Rockhurst University − Jesuit university founded in 1910

- Kansas City Art Institute − four-year college of fine arts and design founded in 1885

- Kansas City University of Medicine and Biosciences − medical and graduate school founded in 1916

- Avila University − Catholic university of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet

- Park University − private institution established in 1875; Park University Graduate School is downtown

- Baker University − multiple branches of the School of Professional and Graduate Studies

- William Jewell College − private liberal arts institution founded in 1849

- Metropolitan Community College (Kansas City) − a two-year college with multiple campuses in the city and suburbs

- Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary − Southern Baptist Convention

- Nazarene Theological Seminary − Church of the Nazarene

- Calvary University

- Saint Paul School of Theology − Methodist

Primary and secondary schools[]

Kansas City is served by 16 school districts including 10 public school districts, with a significant portion being nationally ranked.[101] There are also numerous private schools; Catholic schools in Kansas City are governed by the Diocese of Kansas City.

The following Public School Districts serve Kansas City:[102]

- Kansas City Public Schools (formerly Kansas City, Missouri School District)

- North Kansas City School District

- Center School District

- Hickman Mills C-1 School District

- Grandview C-4 School District

- Liberty School District

- Park Hill School District

- Platte County R-3 School District

- Raytown C-2 School District

- Lees Summit R-7 School District

- Blue Springs R-4 School District

- Independence School District

- Fort Osage R-1 School District

Libraries and archives[]

- Linda Hall Library − internationally recognized independent library of science, engineering and technology, housing over one million volumes.

- Mid-Continent Public Library − largest public library system in Missouri, and among the largest collections in America.

- Kansas City Public Library − oldest library system in Kansas City.

- University of Missouri-Kansas City Libraries − four collections: Leon E. Bloch Law Library and Miller Nichols Library, both on Volker Campus; and Health Sciences Library and Dental Library, both on Hospital Hill in Kansas City.

- Rockhurst University Greenlease Library

- The Black Archives of Mid-America− research center of the African American experience in the central Midwest.

- National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Central Plains Region − one of 18 national records facilities, holding millions of archival records and microfilms for Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska in a new facility adjacent to Union Station, which was opened to the general public in 2008.

Media[]

Print media[]

The Kansas City Star is the area's primary newspaper. William Rockhill Nelson and his partner, Samuel Morss, first published the evening paper on September 18, 1880. The Star competed with the morning Kansas City Times before acquiring that publication in 1901. The "Times" name was discontinued in March 1990, when the morning paper was renamed the "Star".[103]

Weekly newspapers include The Call[104] (which is focused toward Kansas City's African-American community), the Kansas City Business Journal, The Pitch, Ink,[105] and the bilingual publications Dos Mundos and KC Hispanic News.

The city is served by two major faith-oriented newspapers: The Kansas City Metro Voice, serving the Christian community, and the Kansas City Jewish Chronicle, serving the Jewish community. It is the headquarters of the National Catholic Reporter, an independent Catholic newspaper.

Broadcast media[]

The Kansas City media market (ranked 32nd by Arbitron[106] and 31st by Nielsen[107]) includes 10 television stations, 30 FM and 21 AM radio stations. Kansas City broadcasting jobs have been a stepping stone for national television and radio personalities, notably Walter Cronkite and Mancow Muller.

WDAF radio (now at 106.5 FM; original 610 AM frequency now occupied by KCSP) signed on in 1927 as an affiliate of the NBC Red Network, under the ownership of The Star. In 1949, the Star signed on WDAF-TV as an affiliate of the NBC television network. The Star sold off the WDAF stations in 1957, following an antitrust investigation by the United States government (reportedly launched at Truman's behest, following a long-standing feud with the Star) over the newspaper's ownership of television and radio stations. KCMO radio (originally at 810 AM, now at 710 AM) signed on KCMO-TV (now KCTV) in 1953. The respective owners of WHB (then at 710 AM, now at 810 AM) and KMBC radio (980 AM, now KMBZ), Cook Paint and Varnish Company and the Midland Broadcasting Company, signed on WHB-TV/KMBC-TV as a time-share arrangement on VHF channel 9 in 1953; KMBC-TV took over channel 9 full-time in June 1954, after Cook Paint and Varnish purchased Midland Broadcasting's stations.

The major broadcast television networks have affiliates in the Kansas City market (covering 32 counties in northwestern Missouri, with the exception of counties in the far northwestern part of the state that are within the adjacent Saint Joseph market, and northeastern Kansas); including WDAF-TV 4 (Fox), KCTV 5 (CBS), KMBC-TV 9 (ABC), KCPT 19 (PBS), KCWE 29 (The CW), KSHB-TV 41 (NBC) and KSMO-TV 62 (MyNetworkTV). Other television stations in the market include Saint Joseph-based KTAJ-TV 16 (TBN), Kansas City, Kansas-based TV25.tv (consisting of three locally owned stations throughout northeast Kansas, led by KCKS-LD 25, affiliated with several digital multicast networks), Lawrence, Kansas-based KMCI-TV 38 (independent), Spanish-language station KUKC-LD 20 (Univision), Spanish-language station 39 (), and KPXE-TV 50 (Ion Television). The Kansas City television stations also serve as alternates for the Saint Joseph television market due to the short distance between the two cities.

Film community[]

Kansas City has been a locale for film and television productions. Between 1931 and 1982 Kansas City was home to the Calvin Company, a large movie production company that specialized in promotional and sales short films and commercials for corporations, as well as educational films for schools and the government. Calvin was an important venue for Kansas City arts, training local filmmakers who went on to Hollywood careers and also employing local actors, most of whom earned their main income in fields such as radio and television announcing. Kansas City native Robert Altman directed movies at the Calvin Company, which led him to shoot his first feature film, The Delinquents, in Kansas City using many local players.

The 1983 television movie The Day After was filmed in Kansas City and Lawrence, Kansas. The 1990s film Truman, starring Gary Sinise, was filmed in the city. Other films shot in or around Kansas City include Article 99, Mr. & Mrs. Bridge, Kansas City, Paper Moon, In Cold Blood, Ninth Street, and Sometimes They Come Back (in and around nearby Liberty, Missouri). More recently, a scene in the controversial film Brüno was filmed in downtown Kansas City's historic Hotel Phillips.

Today, Kansas City is home to an active independent film community. The Independent Filmmaker's Coalition is an organization dedicated to expanding and improving independent filmmaking in Kansas City. The city launched the KC Film Office in October 2014 with the goal of better marketing the city for prospective television shows and movies to be filmed there. The City Council passed several film tax incentives in February 2016 to take effect in May 2016; the KC Film Office is coordinating its efforts with the State of Missouri to reinstate film incentives on a statewide level.[108] Kansas City was named as a top city to live and work in as a movie maker in 2020.[109]

Infrastructure[]

Originally, Kansas City was the launching point for travelers on the Santa Fe, Oregon, and California trails. Later, with the construction of the Hannibal Bridge across the Missouri River, it became the junction of 11 trunk railroads. More rail tonnage passes through the city than through any other U.S. city. Trans World Airlines (TWA) located its headquarters in the city, and had ambitious plans to turn the city into an air hub.

Highways[]

Missouri and Kansas were the first states to start building interstates with Interstate 70. Interstate 435, which encircles the entire city, is the second longest beltway in the nation. (Interstate 275 around Cincinnati, Ohio is the longest.) The Kansas City metro area has more limited-access highway lane-miles per capita than any other large US metro area, over 27% more than the second-place Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, over 50% more than the average American metropolitan area. From 2013 to 2017 the average commuting time was 21.8 minutes.[110] The Sierra Club blames the extensive freeway network for excessive sprawl and the decline of central Kansas City.[111] On the other hand, the relatively uncongested road network contributes significantly to Kansas City's position as one of America's largest logistics hubs.[112]

Airports[]

Kansas City International Airport, airport code MCI (Mid-Continent International Airport) was built to TWA's specifications to make a world hub.[113] Its original passenger-friendly design placed each of its gates 100 feet (30 m) from the street. Following the September 11, 2001, attacks, it required a costly overhaul to conform to the tighter security protocols. Charles B. Wheeler Downtown Airport was TWA's original headquarters and houses the Airline History Museum. It is still used for general aviation and airshows. As of August, 2021, an entirely new $1.5 billion terminal on the site of the old terminal A, is midway through construction. [114] Designed by Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM), it is a single, advanced technology terminal with 39 gates, initially, that will entirely replace the two remaining terminals, B and C. [115]

Public transportation[]

Like most American cities, Kansas City's mass transit system was originally rail-based. From 1870 to 1957, Kansas City's streetcar system was among the top in the country, with over 300 miles (480 km) of track at its peak. The rapid sprawl in the following years led this private system to be shut down.

KCATA- RideKC[]

On December 28, 1965, the Kansas City Area Transportation Authority (KCATA) was formed via a bi-state compact created by the Missouri and Kansas legislatures. The compact gave the KCATA responsibility for planning, construction, owning and operating passenger transportation systems and facilities within the seven-county area.

RideKC Bus and MAX[]

In July 2005, the KCATA launched Kansas City's first bus rapid transit line, the Metro Area Express (MAX). MAX links the River Market, Downtown, Union Station, Crown Center and the Country Club Plaza.[116] MAX operates and is marketed more like a rail system than a local bus line. A unique identity was created for MAX, including 13 modern diesel buses and easily identifiable "stations". MAX features (real-time GPS tracking of buses, available at every station), and stoplights automatically change in their favor if buses are behind schedule. In 2010, a second MAX line was added on Troost Avenue.[117] The city is planning another MAX line down Prospect Avenue.[118]

The Prospect MAX line launched in 2019 and Mayor Quinton Lucas announced the service would be fare-free indefinitely.[119]

RideKC Streetcar[]

On December 12, 2012, a ballot initiative to construct a $102 million, 2-mile (3200 m) modern streetcar line in downtown Kansas City was approved by local voters.[120] The streetcar route runs along Main Street from the River Market to Union Station; it debuted on May 6, 2016.[121] A new non-profit corporation made up of private sector stakeholders and city appointees – the Kansas City Streetcar Authority – operates and maintains the system. Unlike many similar systems around the U.S., no fare is to be charged initially.[122] Residents within the proposed Transportation Development District are determining the fate of the KC Streetcar's southern extension through Midtown and the Plaza to UMKC. The Port Authority of Kansas City is also studying running an extension to Berkley Riverfront Park.

RideKC Bridj[]

In 2015, the KCATA, Unified Government Transit, Johnson County Transit, and IndeBus began merging from individual metro services into one coordinated transit service for the metropolitan area, called RideKC. The buses and other transit options are branded as RideKC Bus, RideKC MAX, RideKC Streetcar, and RideKC Bridj. RideKC Bridj is a micro transit service partnership between Ford Bridj and KCATA that began on March 7, 2016, much like a taxicab service and with a mobile app. The merger and full coordination is expected to be complete by 2019.[123]

Walkability[]