Kathoey

hideThis article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| กะเทย | |||||

Kathoeys on the stage of a cabaret show in Pattaya | |||||

| Pronunciation | [kàtʰɤːj] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meaning | Trans women, intersex people and effeminate gay men | ||||

| Classification | Gender identity | ||||

| Other terms | |||||

| Synonyms | Ladyboy, phuying praphet song, phet thi sam, sao praphet song | ||||

| Associated terms | Bakla, Khanith, Kothi, Hijra, Two-spirit, Trans woman, Akava'ine | ||||

| Demographics | |||||

| Culture | Thai | ||||

| Frequency | up to 0.6% AMAB (2011 estimate) | ||||

| |||||

| Legal information | |||||

| Recognition | Yes, limited (Thailand) | ||||

| Protection | None (Thailand) | ||||

| Part of a series on |

| Transgender topics |

|---|

|

|

Kathoey or katoey (Thai: กะเทย; RTGS: kathoei Thai pronunciation: [kàtʰɤːj]) is an identity used by some people in Thailand, whose identities in English may be best described as transgender women in some cases, or effeminate gay men in other cases. Transgender women in Thailand mostly use terms other than kathoey when referring to themselves, such as phuying (Thai: ผู้หญิง, 'woman'). A significant number of Thais perceive kathoey as belonging to a separate sex, including some transgender women themselves.[1]

In face of the many sociopolitical obstacles that kathoeys navigate in Thailand, kathoey activism has led to legal recognition as of January 2015.[2]

Terminology[]

A study of 195 Thai transgender women found that most of the participants referred to themselves as phuying (ผู้หญิง 'women'), with a minority referring to themselves as phuying praphet song ('second kind of woman') and only very few referring to themselves as kathoey.[3][better source needed] Related phrases include phet thi sam (เพศที่สาม, 'third sex'), and sao praphet song or phu ying praphet song (สาวประเภทสอง, ผู้หญิงประเภทสอง—both meaning 'second-type female'). The word kathoey is of Khmer origin.[4] It is most often rendered as ladyboy in English conversation, an expression that has become popular across Southeast Asia.[citation needed]

General description[]

Although kathoey is often translated as 'transgender woman' in English, this term is not correct in Thailand. As well as transgender people, the term can refer to gay men, and was originally used to refer to intersex people.[4] Before the 1960s, the use of kathoey included anyone who deviated from the dominant sexual norms.[5] Because of this confusion in translation, the English translation of kathoey is usually 'ladyboy' (or variants of the term).

Use of the term kathoey suggests that the person self-identifies as a type of male, in contrast to sao praphet song (which, like "trans woman", suggests a "female" (sao) identity), and in contrast to phet thi sam ('third sex'). The term phu ying praphet song, which can be translated as 'second-type female', is also used to refer to kathoey.[6]: 146 Australian scholar of sexual politics in Thailand Peter Jackson claims that the term kathoey was used in antiquity to refer to intersex people, and that the connotation changed in the mid-20th century to cover cross-dressing males.[7] Kathoey became an iconic symbol of modern Thai culture.[8] The term can refer to males who exhibit varying degrees of femininity. Many dress as women and undergo "feminising" medical procedures such as breast implants, hormones, silicone injections, or Adam's apple reductions. Others may wear make-up and use feminine pronouns, but dress as men, and are closer to the Western category of effeminate gay man than transgender.

The term kathoey may be considered pejorative, especially in the form kathoey-saloey. It has a meaning similar to the English language 'fairy' or 'queen'.[9] Kathoey can also be seen as a derogatory word for those who self-identify as gay.[10]

Religion[]

Bunmi, a Thai Buddhist author, believes that homosexuality stems from "lower level spirits" (phi-sang-thewada), a factor that is influenced by one's past life.[4] Some Buddhists view kathoeys as persons born with a disability as a consequence of past sins.[4][dubious ]

Requirements to confirm eligibility for gender-affirming surgery[]

In 1965, Johns Hopkins Hospital in the US became the first institution to perform sex-reassignment surgery.[11] Today, in cities such as Bangkok, there are two to three gender-affirming surgery (GAS) operations per week, more than 3,500 over the past thirty years.[12] With the massive increase in GASs, there has also been an increase in prerequisites, measures that must be taken in order to be eligible for the operation. Patients must be at least 18 years old with permission from parents if under 20 years old.[13] One must provide evidence of diagnosis of gender dysphoria from a psychologist or psychiatrist. Before going through gender reassignment surgery, one must be on hormones/antiandrogens for at least one year.[13] Patients must have a note from the psychiatrist or clinical psychologist. Two months prior to the surgery, patients are required to see a psychiatrist in Thailand to confirm eligibility for gender-affirming surgery.

Social context[]

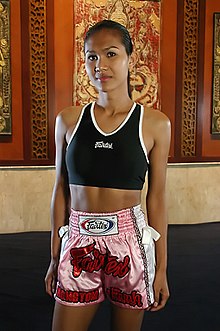

Many kathoey work in predominately female occupations, such as in shops, restaurants, and beauty salons, but also in factories (a reflection of Thailand's high proportion of female industrial workers).[14] Kathoey also work in entertainment and tourist centres, in cabarets, and as sex workers. Kathoey sex workers have high rates of H.I.V.[15]

Kathoeys are more visible and more accepted in Thai culture than transgender people are in other countries in the world. Several popular Thai models, singers and movie stars are kathoeys, and Thai newspapers often print photographs of the winners of female and kathoey beauty contests side by side. The phenomenon is not restricted to urban areas; there are kathoeys in most villages, and kathoey beauty contests are commonly held as part of local fairs.

Using the notion of karma, some Thais believe that being a kathoey is the result of transgressions in past lives, concluding that kathoey deserve pity rather than blame.[16]

A common stereotype is that older, well-off kathoey provide financial support to young men with whom they are in romantic relationships.[17]

Kathoeys currently face many social and legal impediments. Families (and especially fathers) are typically disappointed if a child becomes a kathoey, and kathoeys often have to face the prospect of disclosing their birth gender. However, kathoey generally have greater acceptance in Thailand than most other East Asian countries.[18] Legal recognition of kathoeys and transgender people is nonexistent in Thailand: even if a transgender person has had genital reassignment surgery, they are not allowed to change their legal sex. Discrimination in employment also remains rampant.[19] Problems can also arise in regards to access to amenities and gender allocation; for example, a kathoey and a person who has undergone sexual reassignment surgery would still have to stay in an all-male prison.

Performance[]

Representation in cinema[]

Kathoeys began to gain prominence in the cinema of Thailand during the late-1980s.[20] The depiction at first was negative by showing kathoeys suffering bad karma, suicide, and abandoned by straight lovers.[20] Independent and experimental films contributed to defying sexual norms in gay cinema in the 1990s.[21] The 2000 film The Iron Ladies, directed by Yongyoot Thongkongtoon, depicted a positive portrayal of an almost entirely kathoey volleyball team by displaying their confidence.[20] The rising middle-class in Bangkok and vernacular queer culture made the mainstream portrayal of kathoeys more popular on television and in art house cinemas.[22]

Miss Tiffany's Universe[]

Feminine beauty in Thailand allowed transgender people to have their own platform where they are able to challenge stereotypes and claim cultural recognition.[23] Miss Tiffany's Universe is a beauty contest that is opened to all transgender women. Beginning in 1998, the pageant takes place every year in Pattaya, Thailand during May. With over 100 applicants, the pageant is considered to be one of the most popular transgender pageants in the world. Through beauty pageants, Thailand has been able to promote the country's cosmetic surgery industry, which has had a massive increase in medical tourism for sex reassignment surgery. According to the Miss Tiffany's Universe website, the live broadcast attracts record of fifteen million viewers. The winner of the pageant receives a tiara, sash, car, grand prize of 100,000 baht (US$3,000), equivalent to an annual wage for a Thai factory worker.[24] The assistant manager director, Alisa Phanthusak, stated that the pageant wants kathoeys to be visible and to treat them as normal.[2] It is the biggest annual event in Pattaya.[25]

Transgender beauty contests are found in the countryside at village fairs or festivals.[4] All-male revues are common in gay bars in Bangkok and as drag shows in the tourist resort of Pattaya.[4]

Recent developments[]

In 1993, Thailand's teacher training colleges implemented a semi-formal ban on allowing homosexual (which included kathoey) students enrolling in courses leading to qualification for positions in kindergartens and primary schools. In January 1997, the Rajabhat Institutes (the governing body of the colleges) announced it would formalize the ban, which would extend to all campuses at the start of the 1997 academic year. The ban was quietly rescinded later in the year, following the replacement of the Minister of Education.[6]: xv–xiv

In 1996, a volleyball team composed mostly of gays and kathoeys, known as The Iron Ladies (Thai: สตรีเหล็ก, satree lek), later portrayed in two Thai movies, won the Thai national championship. The Thai government, concerned with the country's image, barred two of the kathoeys from joining the national team and competing internationally.

Among the most famous kathoeys in Thailand is Nong Tum, a former champion Thai boxer who emerged into the public eye in 1998. She would present in a feminine manner and had commenced hormone therapy while still a popular boxer; she would enter the ring with long hair and make-up, occasionally kissing a defeated opponent. She announced her retirement from professional boxing in 1999 – undergoing genital reassignment surgery, while continuing to work as a coach, and taking up acting and modeling. She returned to boxing in 2006.

In 2004, the Chiang Mai Technology School allocated a separate restroom for kathoeys, with an intertwined male and female symbol on the door. The fifteen kathoey students are required to wear male clothing at school but are allowed to sport feminine hairdos. The restroom features four stalls, but no urinals.[26]

Following the 2006 Thai coup d'état, kathoeys are hoping for a new third sex to be added to passports and other official documents in a proposed new constitution.[27] In 2007, legislative efforts have begun to allow kathoeys to change their legal sex if they have undergone genital reassignment surgery; this latter restriction was controversially discussed in the community.[19]

Bell Nuntita, a contestant of the Thailand's Got Talent TV show, became a YouTube hit when she first performed singing as a girl and then switched to a masculine voice.[28]

It is estimated that as many as six in every thousand native males later present themselves as transgender women or phu ying kham phet.[8]

Advocacy[]

Activism[]

Thai activists have mobilized for over two decades to secure sexual diversity rights.[29] Beauty pageant winner Yollada Suanyot, known as Nok, founded the Trans Female Association of Thailand on the basis of changing sex-designation on identification cards for post-operative transsexual women.[29] Nok promoted the term phuying kham-phet instead of kathoey but was controversial because of its connotation with gender identity disease.[29] The goal of the Thai Transgender Alliance is to delist gender dysphoria from international psychological diagnostic criteria and uses the term kathoey to advocate for transgender identity.[29] A common protest sign during sexual rights marches is Kathoey mai chai rok-jit meaning "Kathoey are not mentally ill".[29]

Activism in Thailand is discouraged if it interferes with official policy.[30] In January 2006, the Thai Network of People Living With HIV/AIDS had their offices raided after demonstrations against Thai-US foreign trade agreements.[30] Under the Thai Constitution of 1997, the right to be free of discrimination based on health conditions helped to minimize the stigma against communities living with HIV/AIDS.[30] In most cases, governments and their agencies fail to protect transgender people against these exclusions.[8] There is a lack of HIV/AIDS services for specifically transgender people and feminizing hormones largely go without any medical monitoring.[8]

Trans prejudice has produced discriminatory behaviors that have led to the exclusion of transgender people from economic and social activity.[31] World-wide, transgender people face discrimination amongst family members, religious settings, education, and the work-place.[8] Accepted mainly in fashion-related jobs or show business, people who are transgender are discriminated against in the job market and have limited job opportunities.[29] Kathoeys have also experienced ridicule from coworkers and tend to have lower salaries.[10] Long-term unemployment reduces the chances of contributing to welfare for the family and lowers self-esteem, causing a higher likelihood of prostitution in specialized ladyboy bars.[8] "Ladyboy" bars also can provide a sense of community and reinforces a female sense of identity for kathoeys.[8] Harassment from the police is evident especially for kathoeys who work on the streets.[8] Kathoeys may be rejected in official contexts being rejected entry or services.[10]

Based on a study by AIDS Care participants who identified as a girl or kathoey at an early age were more likely to be exposed to prejudice or violence from men in their families.[15] Kathoeys are more subjected to sexual attacks from men than are other homosexuals.[6]

Anjaree is one of Thailand's gay feminist organizations, established in mid-1986 by women's right activists.[32] The organization advocated wider public understanding of homosexuality based on the principles of human rights. The first public campaign opposing sexual irregularity was launched in 1996.[33]

Social spaces are often limited for kathoeys even if Thai society does not actively persecute them.[10] Indigenous Thai cultural traditions have given a social space for sexual minorities.[8] In January 2015, the Thai government announced it would recognize the third sex in its constitution in order to ensure all sexes be treated equally under the law.[2]

Privacy issues[]

Identity cards are particularly important in Thailand. The vast majority of transgender people in the country were unable to change their documents at all, and those who are able to were held to rather severe standards.[34] Identity cards facilitate many daily activities such as interface with businesses, bureaucratic agencies (i.e., signing up for educational courses or medical care), law enforcement, etc. Impeded by these identity cards on a daily basis, transsexuals are "outed" by society.[35] The requirement facilitated by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (I.C.C.P.R.) that does not offer transgender people the opportunity to change their personal documentation remains as a threat to privacy for the transgender community in Thailand.[35]

Military draft[]

Transgender individuals were automatically exempted from compulsory military service in Thailand. Kathoeys were deemed to suffer from "mental illness" or "permanent mental disorder".[36] These mental disorders were required to appear on their military service documents, which are accessible to future employers. In 2006, the Thai National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) overturned the use of discriminatory phraseology in Thailand's military service exemption documents.[36] With Thai law banning citizens from changing their sex on their identification documents, everyone under the male category must attend a "lottery day" where they are randomly selected to enlist in the army for two years. In March 2008, the military added a "third category" for transgender people that dismissed them from service due to "illness that cannot be cured within 30 days".[37]

In popular culture[]

The first all-kathoey music group in Thailand was formed in 2006. It is named "Venus Flytrap" and was selected and promoted by Sony BMG Music Entertainment.[38] "The Lady Boys of Bangkok" is a kathoey revue that has been performed in the UK since 1998, touring the country in both theatres and the famous "Sabai Pavilion"[39] for nine months each year.

Ladyboys, also a popular term used in Thailand when referring to transgender women, was the title of a popular documentary in the United Kingdom, where it was aired on Channel 4 TV in 1992 and was directed by Jeremy Marre. Marre aimed to portray the life of two adolescent kathoeys living in rural Thailand, as they strove to land a job at a cabaret revue in Pattaya.

The German-Swedish band Lindemann wrote the song "Ladyboy", on their first studio album Skills in Pills, about a man's preference for kathoeys.

In series 1, episode 3 of British sitcom I'm Alan Partridge, the protagonist Alan Partridge frequently mentions ladyboys, seemingly expressing a sexual interest in them.[citation needed]

Thai kathoey style and fashion has largely borrowed from Korean popular culture.[40]

"Uncle Go Paknam"[]

"Uncle Go Paknam", created by Pratchaya Phanthathorn, is a popular non-heterosexual advice column that first appeared in 1975 in a magazine titled Plaek, meaning 'strange'.[5] Through letters and responses it became an outlet to express the desires and necessities of the non-heterosexual community in Thailand.[5] The magazine achieved national popularity because of its bizarre and often gay content.[5] It portrayed positive accounts of kathoeys and men called "sharks" to view transgender people as legitimate or even preferred sexual partners and started a more accepting public discourse in Thailand.[5] Under the pen name of Phan Thathron he wrote the column "Girls to the Power of 2" that included profiles of kathoeys in a glamorous or erotic pose.[5] "Girls to the Power of 2" were the first accounts of kathoey lives based on interviews that allowed their voices to be published in the mainstream press of Thailand.[5] The heterosexual public became more inclined to read about transgender communities that were previously given negative press in Thai newspapers.[5] Go Paknam's philosophy was "kathoeys are good (for men)."[5]

Inside Thailand's Third Gender[]

A documentary entitled Inside Thailand's Third Gender examines the lives of kathoeys in Thailand and features interviews with various transgender women, the obstacles these people face with their family and lovers, but moreover on a larger societal aspect where they feel ostracized by the religious Thai culture. Following contestants participating in one of the largest transgender beauty pageants, known as Miss Tiffany's Universe, the film not only illustrates the process and competition that takes place during the beauty pageant, but also highlights the systems of oppression that take place to target the transgender community in Thailand.[citation needed]

See also[]

|

|

References[]

- ^ Winter, Sam (2003). Research and discussion paper: Language and identity in transgender: gender wars and the case of the Thai kathoey. Paper presented at the Hawaii conference on Social Sciences, Waikiki, June 2003. Article online Archived 29 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Yeung, Isobel. "Trans in Thailand (Part 1)." VICE Video. N.p., n.d. Web. 30 April 2017.

- ^ Winter, Sam (14 June 2006). "Thai Transgenders in Focus: Demographics, Transitions and Identities". International Journal of Transgenderism. 9 (1): 15–27. doi:10.1300/J485v09n01_03. ISSN 1553-2739. S2CID 143719775.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Jackson, Peter A (1989). Male Homosexuality in Thailand; An Interpretation of Contemporary Thai Sources. Elmhurst NY: Global Academic Publishers.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Jackson, Peter A. First Queer Voices from Thailand: Uncle Go's Advice Columns for Gays, Lesbians and Kathoeys. Hong Kong: Hong Kong U Press, 2016. Print.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Jackson, Peter (1999). Lady Boys, Tom Boys, Rent Boys: Male and Female Homosexualities in Contemporary Thailand. Haworth Press. ISBN 978-0-7890-0656-1.

- ^ Jackson, Peter (2003). Performative Genders, Perverse Desires: A Bio-History of Thailand's Same-Sex and Transgender Cultures Archived 3 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine in "Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context," Issue 9, August 2003. See paragraph "The Homosexualisation of Cross-Dressing."

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Winter, Sam. Queer Bangkok: Twenty-first Century Markets, Media, and Rights. Aberdeen, Hong Kong: Hong Kong U Press, 2011

- ^ CPAmedia.com: Thailand's Women of the Second Kind (archive)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Ojanen, Timo T. (2009). "Sexual/gender minorities in Thailand: Identities, challenges, and voluntary-sector counseling". Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 6 (2): 4–34. doi:10.1525/srsp.2009.6.2.4. S2CID 143531913.

- ^ "The News-Letter." Since 1896. N.p., 1 May 2014. 15 March 2017.[full citation needed]

- ^ Gale, Jason (27 October 2015). "How Thailand Became a Global Gender-Change Destination". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Duncan, Debbie. "Prerequisites - The Transgender Center." Prerequisites - The Transgender Center. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 March 2017.

- ^ Winter S, Udomsak N (2002). Male, Female and Transgender: Stereotypes and Self in Thailand Archived 28 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine. International Journal of Transgenderism. 6,1

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nemoto, Tooru (2012). "HIV-Related Risk Behaviors among Kathoey (Male-to-Female Transgender) Sex Workers in Bangkok, Thailand". AIDS Care. 24 (2): 210–9. doi:10.1080/09540121.2011.597709. PMC 3242825. PMID 21780964.

- ^ Totman, Richard (2003). The Third Sex: Kathoey: Thailand's Ladyboys. London: Souvenir Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-285-63668-2.

- ^ Thailand Archived 29 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine, in the International Encyclopedia of Sexuality, Volume I–IV 1997–2001, edited by Robert T. Francoeur

- ^ Roderick, Daffyd (2001). "Boys Will Be Girls: In a Bangkok clinic, $1,000 can turn a man into a woman. Some call that the price of freedom". TIMEasia.com. Time Asia. Archived from the original on 13 April 2001. Retrieved 22 March 2015.. See also Céline Grünhagen: Transgender in Thailand: Buddhist Perspectives and the Socio-Political Status of Kathoeys. In: Gerhard Schreiber (ed.), Transsexuality in Theology and Neuroscience. Findings, Controversies, and Perspectives. De Gruyter, Berlin and Boston 2016, pp. 219–232.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Are you man enough to be a woman? Bangkok Post, 1 October 2007

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Ünaldim Serhat. Queer Bangkok: twenty-first-century markets, media, and rights. Aberdeen, Hong Kong: Hong Kong U Press, 2011. Print.

- ^ Morris, R. C. (1994). "Three Sexes and Four Sexualities: Redressing the Discourses on Gender and Sexuality in Contemporary Thailand". Positions: East Asia Cultures Critique. 2 (1): 15–43. doi:10.1215/10679847-2-1-15.

- ^ Yue, Audrey (2014). "Queer Asian Cinema and Media Studies: From Hybridity to Critical Regionality". Cinema Journal. 53 (2): 145–151. doi:10.1353/cj.2014.0001.

- ^ Jackson, Peter A. Queer Bangkok: twenty-first-century markets, media, and rights. Aberdeen, Hong Kong: Hong Kong U Press, 2011

- ^ "How starring in Miss Tiffany's pageant show can change a Thai trans beauty queen's life." South China Morning Post. N.p., 28 April 2016. Web. 5 March 2017.

- ^ Yeung, Isobel. "Trans in Thailand (Part 2)." VICE Video. N.p., n.d. Web. 30 April 2017.

- ^ "Transvestites Get Their Own School Bathroom", Associated Press, 22 June 2004.

- ^ "Thailand's 'third sex' seeks legal recognition" Archived 23 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine. The First Post. 17 May 2007.

- ^ Winn, Patrick (16 March 2011). "UPDATED: Thai transgender talent show shocker = YouTube gold". GlobalPost. Archived from the original on 8 August 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Käng, Dredge Byung'chu (2012). "Kathoey 'In Trend': Emergent Genderscapes, National Anxieties and the Re-Signification of Male-Bodied Effeminacy in Thailand" (PDF). Asian Studies Review. 36 (4): 475–494. doi:10.1080/10357823.2012.741043. S2CID 143293054.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Cameron, Liz. "Sexual Health and Rights Sex Workers, Transgender People & Men Who have Sex with Men." OPEN SOCIETY INSTITUTE Public Health Program(2006): n. page. Web. 24 March 2017.

- ^ Sam Winter. Queer Bangkok: twenty-first-century markets, media, and rights. Aberdeen, Hong Kong: Hong Kong U Press, 2011. Print.

- ^ Megan Sinnott. Queer Bangkok: twenty-first-century markets, media, and rights. Aberdeen, Hong Kong: Hong Kong U Press, 2011. Print.

- ^ Douglas Sanders. Aberdeen, Hong Kong: Hong Kong U Press, 2011. Print.

- ^ Armbrecht, Jason (11 April 2008). "Transsexuals and Thai Law". Thailand Law Forum. Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Salvá, Ana (1 November 2016). "An LGBTI Oasis? Discrimination in Thailand". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Douglas Sanders. Queer Bangkok: twenty-first-century markets, media, and rights. Aberdeen, Hong Kong: Hong Kong U Press, 2011. Print.

- ^ Chokrungvaranont, Prayuth; Selvaggi, Gennaro; Jindarak, Sirachai; Angspatt, Apichai; Pungrasmi, Pornthep; Suwajo, Poonpismai; Tiewtranon, Preecha (2014). "The Development of Sex Reassignment Surgery in Thailand: A Social Perspective". The Scientific World Journal. 2014: 182981. doi:10.1155/2014/182981. PMC 3977439. PMID 24772010.

- ^ "'Katoeys' hit the music scene" Archived 10 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, The Star, 3 February 2007.

- ^ "The Sabai Pavilion | The Lady Boys of Bangkok". The Lady Boys of Bangkok. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- ^ Blackwood, Evelyn; Johnson, Mark (2012). "Queer Asian Subjects: Transgressive Sexualities and Heteronormative Meanings" (PDF). Asian Studies Review. 36 (4): 441–451. doi:10.1080/10357823.2012.741037. S2CID 145600356.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kathoeys. |

| Look up kathoey in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Andrew Matzner, In Legal Limbo: Thailand, Transgender Men, and the Law, 1999. Criticizes the common view that kathoey are fully accepted by Thai society.

- Andrew Matzner, Roses of the North: The Katoey of Chiang Mai University, 1999. Reports on a kathoey "sorority" at Chiang Mai University.

- Transgender Asia including several articles on kathoey

- Where the 'Ladyboys' Are

- Ladyboy: Thailand's Theater of Illusion. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012. ASIN: B0085S4WQC

- Can you tell the difference between Katoeys and real ladies?"

- E.G. Allyn: Trees in the Same Forest, 2002. Description of the gay and kathoey scene of Thailand.

- Chanon Intramart and Eric Allyn, Beautiful Boxer, 2003. Describes the story of Nong Tum.

- The Hermaphrodite World is a film exploring the kathoey culture of Thailand

- Katoey Thai-Ladyboys

- Farrell, James Austin. "The price of change and the right to be a woman in Thailand", Asian Correspondent, 2015-12-14.

- Kathoey

- Gender systems

- Thai culture

- Third gender

- LGBT culture in Thailand

- Transgender in Asia

- LGBT terminology