Kenpeitai

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2009) |

| Kenpeitai | |

|---|---|

| 憲兵隊 | |

Kenpeitai logo found on officer’s armbands | |

| Active | 1881–1945 |

| Disbanded | August 1945 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Gendarmerie, Military police and Secret police |

| Role | Various duties including judicial, counterinsurgency and military roles |

| Size | over 36,000 (c. 1945) |

| Part of | Home Ministry (within the Japanese home islands) Ministry of the Army (overseas territories) |

The Kenpeitai (憲兵隊, "Military Police Corps", /kɛnpeɪˈtaɪ/), also known as Kempeitai, was the military police arm of the Imperial Japanese Army from 1881 to 1945. It was both a conventional military police and a secret police force. In Japanese-occupied territories, the kenpeitai also arrested or killed those who were suspected of being anti-Japanese. While it was institutionally part of the army, the Kenpeitai also discharged the functions of the military police for the Imperial Japanese Navy under the direction of the Admiralty Minister (although the IJN had its own much smaller Tokkeitai), those of the executive police under the direction of the Home Minister and those of the judicial police under the direction of the Justice Minister. A member of the corps was called a kenpei (憲兵).[1]

History[]

The Kenpeitai was established in 1881 by a decree called the Kenpei Ordinance (憲兵条例), figuratively "articles concerning gendarmes".[2] Its model was the National Gendarmerie of France. Details of the Kenpeitai's military, executive, and judicial police functions were defined by the Kenpei Rei of 1898,[3] which was amended twenty-six times before Japan's defeat in August 1945.

The force initially consisted of 349 men. The enforcement of the new conscription legislation was an important part of their duty, due to resistance from peasant families. The Kenpeitai's General Affairs Branch was in charge of the force's policy, personnel management, internal discipline, as well as communication with the Ministries of the Admiralty, the Interior, and Justice. The Operations Branch was in charge of the distribution of military police units within the army, general public security and intelligence.[citation needed]

In 1907, the Kenpeitai was ordered to Korea[4] where its main duty was legally defined as "preserving the peace", although it also functioned as a military police for the Japanese Army stationed there. This status remained basically unchanged after Japan's annexation of Korea in 1910.

The Kenpeitai maintained public order within Japan under the direction of the Interior Minister, and in the occupied territories under the direction of the Minister of War. Japan also had a civilian secret police force, Tokkō, which was the Japanese acronym of Tokubetsu Kōtō Keisatsu ("Special Higher Police") part of the Interior Ministry. However, the Kenpeitai had a Tokkō branch of its own, and through it discharged the functions of a secret police.

When the Kenpeitai arrested a civilian under the direction of the Justice Minister, the arrested person was nominally subject to civilian judicial proceedings.

The Kenpeitai's brutality was particularly notorious in Korea and the other occupied territories. The Kenpeitai were also abhorred in Japan's mainland as well, especially during World War II when Prime Minister Hideki Tojo, formerly the Commander of the Kenpeitai of the Japanese Army in Manchuria from 1935 to 1937,[5] used the Kenpeitai extensively to make sure that everyone was loyal to the war.

According to United States Army TM-E 30-480, there were over 36,000 regular members of the Kenpeitai at the end of the war; this did not include the many ethnic "auxiliaries". As many foreign territories fell under the Japanese military occupation during the 1930s and the early 1940s, the Kenpeitai recruited a large number of locals in those territories. Taiwanese and Koreans were used extensively as auxiliaries to police the newly occupied territories in Southeast Asia, although the Kenpeitai recruited French Indochinese (especially, from among the Cao Dai religious sect), Malays and others. The Kenpeitai may have trained Trình Minh Thế, a Vietnamese nationalist and anti-Viet Minh military leader.

The Kenpeitai was disarmed and disbanded after the Japanese surrender in August 1945.

Today, the post-war Self-Defense Forces' internal police is called Keimutai (警務隊). Each individual member is called Keimukan. Modelled on the Military Police in the United States and other Western armed forces, they have no jurisdiction over civilians.

Axis powers[]

This article possibly contains original research. (January 2021) |

This section does not cite any sources. (January 2021) |

In the 1920s and the 1930s, the Kenpeitai forged various connections with certain prewar European intelligence services. Later, when Japan signed the Tripartite Pact, Japan formed formal links with the intelligence units, now under German and Italian fascists, known as the German Abwehr and the Italian Servizio Informazioni Militare. The army and the navy of Japan contacted their corresponding Wehrmacht intelligence units, Schutzstaffel (SS) or Kriegsmarine, about information on Europe and vice versa. Europe and Japan realized the benefits of the exchanges. For example, the Japanese sent data about Soviet forces in the Far East and in Operation Barbarossa from the Japanese embassy. Admiral Canaris offered aid in respect to the neutrality of Portugal in Timor.

One important contact point was at the Penang submarine base, in occupied Malaya. The base served Axis submarine forces (Italian Regia Marina, German Kriegsmarine and the Dai Nippon Teikoku Kaigun, or Imperial Japanese Navy). At regular intervals, technological and information exchanges occurred there. While these were available to them, Axis forces used the bases in Italian East Africa, the Vichy France colony of Madagascar and some officially neutral places like Portuguese India.

Human rights abuses[]

The Kenpeitai ran extensive criminal and collaborationist networks, extorting vast amounts of money from businesses and civilians wherever they operated. They also ran the Allied prisoner of war system, which often treated captives with extreme brutality.[6][7] Many of the abuses were documented in Japanese war crimes trials, such as those committed by the Kempeitai East District Branch in Singapore.

The Kenpeitai also carried out revenge attacks against prisoners and civilians. For example, after Colonel Doolittle's raid on Tokyo in 1942, the Kenpeitai carried out reprisals against thousands of Chinese civilians and captured airmen,[8] or in 1943 the Double Tenth massacre which was in response to an Allied raid on Singapore Harbour. They also supplied 600 men, women and children per year for Unit 731, where infamous human experiments were conducted.[9]

Organization[]

This section called "Organization" needs additional citations for verification. (August 2010) |

The Kenpeitai maintained a headquarters in each relevant Area Army, commanded by a Shosho (Major General) with a Taisa (Colonel) as Executive Officer and comprising two or three field offices, commanded by a Chusa (Lieutenant Colonel) and with a Shosa (Major) as executive officer and each with approximately 375 personnel.

The field office in turn was divided into 65-man sections called 'buntai'. Each was commanded by a Tai-i (Captain) with a Chu-i (1st Lieutenant) as his Executive Officer and had 65 other troops. The buntai were further divided into detachments called bunkentai, commanded by a Sho-i (2nd Lieutenant) with a Junshikan (Warrant Officer) as Executive Officer and 20 other troops. Each detachment contained three squads: a police squad or keimu han, an administration squad or naikin han, and a special duties squad or Tokumu han.

Kenpeitai Auxiliary units consisting of regional ethnic forces were organized in occupied areas. These troops supplemented the Kenpeitai and were considered part of the organization but were limited to the rank of Socho (Sergeant Major).

By 1937 the Kenpeitai had 315 officers and 6,000 enlisted. These were the members of the known, public forces. The Allies estimated that by the end of World War II, there were at least 7,500 members[10] of the Kenpeitai.

Active units[]

The Kenpeitai operated commands on the Japanese mainland and throughout all occupied and captured overseas territories during the Pacific War. The external units operating outside Japan were:

- First Field Kenpeitai – was commanded by Major-General Kōichi Ōno from August 1941 to 23 January 1942 and probably based in China with Kwangtung Army

- Second Field Kenpeitai – attached to the 25th Army and based in Singapore from 1942. The unit was under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel . In January 1944 Malaya came under 3rd Field Kempeitai Major-General .[11]

- Third Field Kenpeitai – was drawn from a Manchurian Kenpei Training Regiment in July 1941 and then attached to the 16th Army and based in Java and Sumatra from 1942. The units headquarters was in Batavia under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel . By wars end there were 772 members of the unit.[12]

- Fourth Field Kenpeitai

- Fifth Field Kenpeitai

- Sixth Field Kenpeitai – attached to the 8th Area Army based at Rabaul[13]

- Seventh Field Kenpeitai

- Eighth Field Kenpeitai – attached to the 2nd Army on Halmahera

- Ninth Field Kenpeitai

- Tenth Field Kenpeitai

- Eleventh Field Kenpeitai – commanded by Colonel from November 1941 to August 1942, when he became head of the 1st Army Kenpeitai Southern Section

Wartime mission[]

The Kenpeitai was responsible for the following:

- Travel permits

- Labor recruitment

- Counterintelligence and counter-propaganda (run by the Tokko-Kenpeitai as 'anti-ideological work')

- Supply requisitioning and rationing

- Psychological operations and propaganda

- Rear area security

By 1944, despite the obvious tide of war, the Kenpeitai were arresting people for antiwar sentiment and defeatism.[14]

Uniform[]

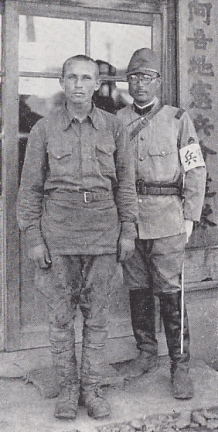

Personnel wore either the standard M1938 field uniform or the cavalry uniform with high black leather boots. Civilian clothes were also authorized but badges of rank or the Japanese Imperial chrysanthemum were worn under the jacket lapel. Uniformed personnel also wore a black chevron on their uniforms and a white armband on the left arm with the characters ken (憲, "law") and hei (兵, "soldier"), together read as kenpei or kempei, which translates to "military policeman".

A full dress uniform comprising a red kepi, gold and red waist sash, dark blue tunic and trousers with black facings was authorized for officers of the Kenpeitai to wear on ceremonial occasions until 1942. Rank insignia comprised gold Austrian knots and epaulettes.

Personnel were armed with either a cavalry sabre and pistol for officers and a pistol and bayonet for enlisted men. Junior NCOs carried a shinai (竹刀, "bamboo kendo sword") especially when dealing with prisoners.

Other intelligence sections[]

- Kenpeitai (Imperial Japanese Gendarmerie) had responsibilities similar to German Schutzstaffel ("SS") and Sicherheitsdienst ("SD") (German Security Service) or Soviet Russian NKVD, and Politruk unit, for watching exterior enemies or suspicious persons and watching inside of own unit for possible defectors or traitors; and used the security doctrine of "Kikosaku".

- Overseas Security and Colonial Police Service special unit dedicated to the maintenance of security in occupied territories in Southeast Asia. This also undertook some administrative responsibilities.

- The Kenpeitai was divided into:

- Keimu Han (Police and security)

- Naikin Han (Administration)

- Tokumu Han (Special Duties)

See also[]

- Internal security

- List of Japanese spies, 1930–45

- Police services of the Empire of Japan (Keishichō, to 1945)

- Unit 100

- Fukushima Yasumasa (founder of the Kenpeitai)

- Tenko (TV series)

- The Man in the High Castle (TV series)

References[]

- ^ Takahashi, Masae (editor and annotator), Zoku Gendaishi Shiryo ("Materials on Contemporary History, Second Series"), Volume 6, Gunji Keisatsu ("Military Police"), (Tokyo: Misuzu Shobo, 1982), pp. v–xxx.

- ^ Dajokan-Tatsu (Decree in Grand Council of the State) of 11 March 1881 (14th Year of Meiji), No. 11. This decree was subsequently amended by Chokurei (Order in Privy Council) of 28 March 1889 (22nd Year of Meiji), No. 43.

- ^ Order in Privy Council of 29 November 1898 (31st year of Meiji), No. 337.

- ^ Order in Privy Council of 1907 (40th Year of Meiji), No. 323.

- ^ Naohiro Asao, et al. ed., Simpan Nihonshi Jiten ("Dictionary of Japanese History, New Edition", Tokyo: Kadokawa Shoten, 1997) p. 742 ("Tojo Hideki"), and pp. 348–9 ("Kempei").

- ^ results, search (25 November 1998). Kempeitai: Japan's Dreaded Military Police. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0750915668.

- ^ Blundell, Nigel (2 August 2009). "Demons of depravity: the Japanese Gestapo".

- ^ Felton, Mark (10 October 2018). "Japan's Gestapo: Murder, Mayhem and Torture in Wartime Asia". Pen & Sword Military – via Google Books.

- ^ Yuki Tanaka, Hidden Horrors, Westviewpress, 1996, p. 138

- ^ Cortazzi, Hugh (1 February 1990). "The Japanese achievement". Sidgwick and Jackson – via Google Books.

- ^ Malaya in World War 2, C Peter Chen, retrieved 9 August 2018

- ^ The Kenpeitai in Java and Sumatra, Barbara Gifford Shimer and Guy Hobbs, Equinox Publishing, 2010, pages 33-34 ISBN 6028397105, 9786028397100

- ^ Rabaul Prisoner Compound (Rabaul POW Prison), Casurine Street and Konbue Street, Rabaul, retrieved 9 August 2018

- ^ Edwin P. Hoyt, Japan's War, p 397 ISBN 0-07-030612-5

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kempeitai. |

- Imperial Japanese Army

- Political repression in Japan

- Defunct Japanese intelligence agencies

- Defunct law enforcement agencies of Japan

- Defunct military provosts

- Intelligence services of World War II

- Secret police