LGBT history in the United States

| Part of a series on |

| LGBT topics |

|---|

|

|

|

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of the United States |

|---|

|

|

LGBT history in the United States spans the contributions and struggles of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals as well as the coalitions they've built. States like California, New Jersey, Colorado, Oregon, and Illinois have public school curricula that legally require LGBT history lessons, including prominent gay people and LGBT-rights milestones, in history classes.[4] [5]

18th–19th century[]

With the establishment of the United States following the American Revolution, such crimes as "sodomy" were considered to be a capital offense in some states, while cross-dressing was considered a felony punishable by imprisonment or other forms of corporal punishment.[6]

Noah Webster published the original Webster's American Dictionary of the English Language (Webster's Dictionary) in 1828. He included several LGBT terms in his book. Webster, however, focused on terms for gay sexual practices and ignored lesbian sexual practices: bugger, [7] buggery, [8] pathic, [9] pederast, [10] pederastic, [11] pederasty, [12] sodomy, [13] and sodomite, [14] He occasionally cited the King James Version. For example, Webster cited First Epistle to the Corinthians VI to define the homosexual context of the term abuser.[15] Another citation is the Book of Genesis 18 to associate the term, cry to the Sodom and Gomorrah.[16] Both American Presidents James Buchanan and his successor Abraham Lincoln were speculated to be homosexual. The sexuality of Abraham Lincoln has been considered for over a century. Perhaps the greatest proof to connect Lincoln and homosexuality is a poem that he wrote in his youth that reads: "But Billy has married a boy."[17]

LGBT persons were present throughout the post-independence history of the country, with gay men having served in the Union Army during the American Civil War.[18] The United States saw the rise of its own Uranian poetry after the Uranian ("Urnings") movement began to rise in the Western world. Walt Whitman denied his homosexuality in a letter after asked outright about his sexual orientation by John Addington Symonds.[19][20] Horatio Alger, another Civil War-era writer, became a disgraced minister in 1866 after it was discovered that he was guilty of pederasty.[21] Bayard Taylor wrote Joseph and His Friend: A Story of Pennsylvania in 1870. Archibald Clavering Gunter wrote a lesbian story in 1896 that would serve for the 1914 film, "A Florida Enchantment."

Restrictions against loitering and solicitation of sex in public places were installed in the late 19th century by many states (namely to target, among other things, solicitation for same-sex sexual favors), and increasingly tighter restrictions upon "perverts" were common by the turn of the century.[citation needed] Sodomy laws in the United States were enacted separately over the course of four centuries and varied state by state.

Several examples of same-sex couples living in relationships that functioned as marriages, even if they could not be legally sanctified as such, have been located by historians.[22] Rachel Hope Cleves documents the relationship of 19th-century Vermont residents Charity Bryant and Sylvia Drake in her 2014 book Charity and Sylvia: A Same-Sex Marriage in Early America,[22] and Susan Lee Johnson included the story of Jason Chamberlain and John Chaffee, a California couple who were together for over 50 years until Chaffee's death in 1903, in her 2000 book Roaring Camp: The Social World of the California Gold Rush.[23] Around 1890, former acting First Lady Rose Cleveland started a lesbian relationship with Evangeline Marrs Simpson, with explicitly erotic correspondence;[24] this cooled when Evangeline married Henry Benjamin Whipple, but after his death in 1901 the two rekindled their relationship and in 1910 they moved to Italy together.[25][26][27]

Henry Oliver Walker was permitted in 1898 to paint a mural in the Library of Congress. What the eccentric artist painted was shocking to pious sympathies: a mural of the catamite Ganymede with Zeus in the depiction of an eagle, which was derived from Greek mythology

The first person known to describe himself as a drag queen was William Dorsey Swann, born enslaved in Hancock, Maryland. Swann was the first American on record who pursued legal and political action to defend the LGBTQ community's right to assemble.[28] During the 1880s and 1890s, Swann organized a series of drag balls in Washington, D.C. Swann was arrested in police raids numerous times, including in the first documented case of arrests for female impersonation in the United States, on April 12, 1888.[29]

1900–1969[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2017) |

In the United States, as early as the turn of the 20th century several groups worked in hiding to avoid persecution and to advance the rights of homosexuals, but little is known about them.[30] Edward Irenaeus Prime-Stevenson published Imre: A Memorandum in 1906 and The Intersexes in 1908.[31] A better documented group is Henry Gerber's Society for Human Rights (formed in Chicago in 1924), which was quickly suppressed within months of its establishment.[32] Serving as an enlisted man in occupied Germany after World War I, Gerber had learned of Magnus Hirschfeld's pioneering work. Upon returning to the U.S. and settling in Chicago, Gerber organized the first documented public homosexual organization in America and published two issues of the first gay publication, entitled Friendship and Freedom. Meanwhile, during the 1920s, LGBT persons found employment as entertainers or entertainment assistants for various urban venues in cities such as New York City.[33]

Homosexuals were occasionally seen in LGBT films of Pre-Code Hollywood. Buster Keaton's Seven Chances offered a rare joke about the female impersonator, Julian Eltinge. The Pansy Craze offered actors, such as Gene Malin, Ray Bourbon, Billy De Wolfe, Joe Besser, and Karyl Norman. In 1927, Mae West was jailed for The Drag. The craze found itself in a wide variety of American films, from gangster films like The Public Enemy, to musicals like Wonder Bar and animated cartoons like Dizzy Red Riding Hood. Homosexuals even managed to find themselves in the then-illegal pornographic film industry.

Around 1929, "The Surprise of a Knight" became the first American gay pornographic film. "" would be the second American gay pornographic film

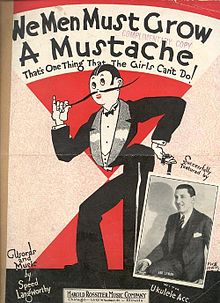

Homosexuality was also present in the music industry. In 1922, Norval Bertrand Langworthy (better known as Speed Langworthy) (b. May 15, 1901, Seward, Nebraska - d. March 22, 1999, Arizona)[34] wrote the song, ""; Abe Lyman appeared on the sheet music. Edgar Leslie and James V. Monaco wrote ""[35] in Hugh J. Ward's 1926 production of the musical Lady Be Good.[35] Homosexuality also found its way into African-American music. Ma Rainey, who is believed to be a lesbian, recorded the song, "." According to pbs.org, the song is about her arrest for group sex, in which alleged lesbianism took place.[36] George Hannah decided in 1930 to record the song, "."[37] Kokomo Arnold recorded the song, "Sissy Man Blues" in 1935.[38] Pinewood Tom (Josh White), , and followed with their own records.[39]

While it seems that homosexuals enjoyed greater recognition in the media after World War I, many were still arrested and convicted for their deeds through state sodomy laws. For example, Eva Kotchever headed a lesbian café called Eve's Hangout in Greenwich Village. It was stated about her business that "men are admitted but not welcome." Kotchever's discretion had been so reckless, she wrote about lesbianism in her book, Lesbian Love. In 1926, the New York City Police Department raided her club and Kotchever was arrested on an obscenity charge and deported to her native Poland.[40]

In 1948, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male was published by Alfred Kinsey, a work which was one of the first to look scientifically at the subject of sexuality. Kinsey claimed that approximately 10% of the adult male population (and about half that number among females) were predominantly or exclusively homosexual for at least three years of their lives.[41]

During the late 1940s – 1960s, a handful of radio and television news programs aired episodes that focused on homosexuality, with some television movies and network series episodes featuring gay characters or themes.[42] The homophile movement began in the 1950s and 60s with the creation of several organizations, including the Mattachine Society, the Daughters of Bilitis and the Society for Individual Rights.

In 1958, the United States Supreme Court ruled that the gay publication ONE, Inc., was not obscene and thus protected by the First Amendment.[43] The California Supreme Court extended similar protection to Kenneth Anger's homoerotic film, Fireworks and Illinois became the first state to decriminalize sodomy between consenting adults in private.[44]

Little change in the laws or mores of society was seen until the mid-1960s, the time the sexual revolution began. Gay pulp fiction and Lesbian pulp fiction ushered in a new era. The physique movement also emerged with Mr. America. Athletic Model Guild produced much of the homoerotic content that proceeded the gay pornography business. This was a time of major social upheaval in many social areas, including views of gender roles and human sexuality.

1969–1999[]

Gay Liberation[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2017) |

In the late 1960s, the more socialistic "liberation" philosophy that had started to create different factions within the Civil Rights Movement, Black Power movement, anti-war movement, and Feminist movement, also engulfed the homophile movement. A new generation of young gay and lesbian Americans saw their struggle within a broader movement to dismantle racism, sexism, western imperialism, and traditional mores regarding drugs and sexuality. This new perspective on Gay Liberation had a major turning point with the Stonewall riots in 1969.

In the early hours of June 28, 1969, the police raided a gay/transgender bar known as the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, Manhattan, a common police practice at the time. This type of raid, which was often conducted during city elections, witnessed a new development as some of the patrons in the bar began actively resisting the police arrests. Some of what followed is in dispute, but what is not in dispute is that for the first time a large group of LGBT Americans who had previously had little or no involvement with the organized gay rights movement rioted for three days against police harassment and brutality. These new activists were not polite or respectful but rather angry activists who confronted the police and distributed flyers attacking the Mafia control of the gay bars and the various anti-vice laws that allowed the police to harass gay men and gay drinking establishments. This second wave of the gay rights movement is often referred to as the Gay Liberation movement to draw a distinction with the previous homophile movement.

New gay liberation organizations were created such as the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) in New York City and the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA). In keeping with the mass frustration of LGBT people, and the adoption of the socialistic philosophies that were being propagated in the late 1960s–1970s, these new organizations engaged in colorful and outrageous street theater (Gallagher & Bull 1996). The GLF published "A Gay Manifesto" that was influenced by Paul Goodman's work titled "The Politics of Being Queer" (1969).

The gay liberation movement spread to countries throughout the world and heavily influenced many of the modern gay rights organizations. Out of this vein, a number of modern-day advocacy organizations were established with differing approaches: the Human Rights Campaign, formed in 1980, follows a more middle class-oriented and reformist tradition, while other organizations such as the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force (NGLTF), formed in 1973, tries to be grassroots-oriented and support local and state groups to create change from the ground up.

The group Dyketactics was the first LGBT group in the U.S. to take the police to court for police brutality in the case Dyketactics vs. The City of Philadelphia. Members of Dyketactics who took the police to court, now known as "The Dyketactics Six," were beaten by the Philadelphia Civil Defence Squad in a demonstration for LGBT rights on December 4, 1975.[45]

Thomas Szasz was one of the earliest scholars to challenge the idea of homosexuality as a mental disorder. In his book Ceremonial Chemistry (1973), he claimed that the same persecution that targeted witches, Jews, gypsies, and homosexuals now targeted "drug addicts" and "insane" people.[citation needed]

Gay migration[]

In the 1970s many gay people moved to cities such as San Francisco.[46] Harvey Milk, a gay man, was elected to the city's Board of Supervisors, a legislative chamber often known as a city council in other municipalities.[47] Milk was assassinated in 1978 along with the city's mayor, George Moscone.[48] The White Night Riot on May 21, 1979 was a reaction to the manslaughter conviction and sentence given to the assassin, Dan White, which were thought to be too lenient. Milk played an important role in the gay migration and in the gay rights movement in general.[49][50]

The first national gay rights march in the United States took place on October 14, 1979 in Washington, D.C., involving perhaps as many as 100,000 people.[51][52]

Historian William A. Percy considers that a third epoch of the gay rights movement began in the early 1980s, when AIDS received the highest priority and decimated its leaders, and lasted until 1998, when advanced antiretroviral therapy greatly extended the life expectancy of those with AIDS in developed countries.[53] It was during this era that direct action groups such as ACT UP were formed.[54]

Decriminalization of relations[]

In 1962, consensual sexual relations between same-sex couples was decriminalized in Illinois, the first time that a state legislature took such an action. Over the next several decades, such relations were gradually decriminalized on a state-by-state basis. Connecticut was the next state to decriminalize homosexuality.[55] Colorado,[56] Oregon,[57] Delaware[58] all had decriminalized homosexuality by 1973. Ohio,[59] Massachusetts,[60] North Dakota,[61] New Mexico,[62] New Hampshire,[63] California,[64] West Virginia,[65] Iowa,[66] Maine,[67] Indiana,[68] South Dakota,[69] Wyoming,[70] Nebraska,[71] Washington,[72] New York[73] all decriminalized homosexuality in the 1970s.

In the 1980s, Pennsylvania[73] and Wisconsin.[74]

May 1990 Mica England filed a lawsuit against the Dallas Police Department for discrimination and in 1994 overturned the hiring policy. Mica England vs State of Texas, City of Dallas, and Police Chief Mack Vines. This had a statewide effect on state government employment. The Mica England Lawsuit also turned of the Homosexual Conduct Law in 34 counties in the First District Court of Appeal and the Third District Court of Appeal. A late appeal by the Dallas city Attorney at the State Supreme Court level caused the Supreme Court unable to rule for the whole state of Texas or otherwise the 21.06 statute would have been overturned statewide. The Mica England case is referred to and is used for discovery in current discrimination lawsuits. In the 1990s, Kentucky,[75] Nevada,[76] Tennessee,[77] Montana,[78] Rhode Island.[79]

In 2003, the Supreme Court decriminalized homosexuality in the decision with Lawrence v. Texas, in Alabama, Florida, Idaho, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri (statewide), North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas, Utah, and Virginia.

"Don't ask, don't tell" and DOMA[]

The long-standing prohibition on open homosexuals serving in the United States military was reinforced under "Don't ask, don't tell" (DADT), a 1993 Congressional policy which allowed for homosexual people to serve in the military provided that they did not disclose their sexual orientation. The Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) of 1996 also barred the federal government from recognizing same-sex couples in any legal manner.

21st century[]

The tipping point of activism in favor of same-sex marriage came in 2008, when the California State Supreme Court ruled that the previous proposition which barred the legalization of same-sex marriage in California was unconstitutional under the United States Constitution. Over 18,000 couples then obtained legal licenses from May until November of the same year, when another statewide proposition reinstated the ban on same-sex marriage. This was received by nationwide protests against the ban and a number of legal battles which were projected to end up in the Supreme Court of the United States.

In the late 2000s and early 2010s, attention was also paid to the rise of suicides and the lack of self-esteem by LGBT children and teenagers due to homophobic bullying. The "It Gets Better Project", founded and promoted by Dan Savage, was launched in order to counter the phenomenon, and various initiatives were taken by both activists and politicians to impose better conditions for LGBT students in public schools.

On June 12, 2016, 49 people, mostly of Latino descent, were shot and killed by Omar Mateen during Latin Night at the Pulse gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida. The shooting was the second deadliest mass shooting and worst act of violence against the LGBT community in American history. Mateen was probably a frequent visitor to Pulse gay night club. People who knew Mateen have speculated if he could be gay or bisexual himself. A colleague at the police academy in 2006 said he frequented gay clubs with Mateen and that on several occasions he expressed interest in having sex. People who frequent clubs also remember Mateen dancing with other men.[80][circular reference] His ex-wife, Sitora Yusufiy, declared three days after the shooting that Mateen might have been hiding homosexuality from his family.[81]

Presidency of Barack Obama[]

The election of Barack Obama as the first African-American president of the United States (on the same day as the California ban on same-sex marriage was enacted) signified the beginning of a more nuanced federal policy to LGBT citizens. Obama advocated for the repeal of DADT, which was passed in December 2010, and also withdrew legal defense of DOMA in 2011, despite Republican opposition. The Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2010 was also the first major hate crimes legislation in federal legislation history to recognize gender identity as a protected class.[82][citation needed]

2009[]

President Barack Obama took many definitive pro-LGBT rights stances. In 2009, his administration reversed Bush administration policy and signed the U.N. declaration that calls for the decriminalization of homosexuality.[83] In June 2009, Obama became the first president to declare the month of June to be LGBT pride month; President Clinton had declared June Gay and Lesbian Pride Month.[84][85] Obama did so again in June 2010,[86] June 2011,[87] June 2012,[88] June 2013,[89] June 2014,[90] and June 2015.[91]

On June 17, 2009, President Obama signed a presidential memorandum allowing same-sex partners of federal employees to receive certain benefits. The memorandum does not cover full health coverage.[92] On October 28, 2009, Obama signed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, which added gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, and disability to the federal hate crimes law.[93]

In October 2009, he nominated Sharon Lubinski to become the first openly lesbian U.S. marshal to serve the Minnesota district.[94]

2010[]

On January 4, 2010, he appointed Amanda Simpson the Senior Technical Advisor to the Department of Commerce, making her the first openly transgender person appointed to a government post by a U.S. President.[95][96][97] He had appointed the most U.S. gay and lesbian officials of any U.S. president, at the time.[98]

At the start of 2010, the Obama administration included gender identity among the classes protected against discrimination under the authority of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). On April 15, 2010, Obama issued an executive order to the Department of Health and Human Services that required medical facilities to grant visitation and medical decision-making rights to same-sex couples.[99] In June 2010, he expanded the Family Medical Leave Act to cover employees taking unpaid leave to care for the children of same-sex partners.[100] On December 22, 2010, Obama signed the Don't Ask, Don't Tell Repeal Act of 2010 into law.[101]

2011[]

On February 23, 2011, President Obama instructed the Justice Department to stop defending the Defense of Marriage Act in court.[102]

In March 2011, the U.S. issued a nonbinding declaration in favor of gay rights that gained the support of more than 80 countries at the U.N.[103] In June 2011, the U.N. endorsed the rights of gay, lesbian, and transgender people for the first time, by passing a resolution that was backed by the U.S., among other countries.[103]

On August 18, 2011, the Obama administration announced that it would suspend deportation proceedings against many undocumented immigrants who pose no threat to national security or public safety, with the White House interpreting the term "family" to include partners of lesbian, gay and bisexual people.[104]

On September 30, 2011, the Defense Department issued new guidelines that allow military chaplains to officiate at same-sex weddings, on or off military installations, in states where such weddings are allowed.[105]

On December 5, 2011, the Obama administration announced the United States would use all the tools of American diplomacy, including the potent enticement of foreign aid, to promote LGBT rights around the world.[106]

2012[]

In March and April 2012, Obama expressed his opposition to state constitutional bans on same-sex marriage in North Carolina, and Minnesota.[107]

On May 3, 2012, the Federal Bureau of Prisons has agreed to add an LGBT representative to the diversity program at each of the 120 prisons it operates in the United States.[108]

On May 9, 2012, Obama publicly supported same-sex marriage, the first sitting U.S. President to do so. Obama told an interviewer that:[109]

over the course of several years as I have talked to friends and family and neighbors when I think about members of my own staff who are in incredibly committed monogamous relationships, same-sex relationships, who are raising kids together, when I think about those soldiers or airmen or Marines or sailors who are out there fighting on my behalf and yet feel constrained, even now that Don't Ask Don't Tell is gone, because they are not able to commit themselves in a marriage, at a certain point I've just concluded that for me personally it is important for me to go ahead and affirm that I think same sex couples should be able to get married.

In the 2012 election, Obama received the endorsement of the following gay rights organizations: Equal Rights Washington, Fair Wisconsin, Gay-Straight Alliance,[110][111] Human Rights Campaign,[112] and the National Stonewall Democrats. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) gave Obama a score of 100% on the issue of gays and lesbians in the US military and a score of 75% on the issue of freedom to marry for gay people.[113]

2013[]

On January 7, 2013, the Pentagon agreed to pay full separation pay to service members discharged under "Don't Ask, Don't Tell."[114]

Obama also called for full equality during his second inaugural address on January 21, 2013: "Our journey is not complete until our gay brothers and sisters are treated like anyone else under the law—for if we are truly created equal, then surely the love we commit to one another must be equal as well." It was the first mention of rights for gays and lesbians or use of the word gay in an inaugural address.[115][116]

On March 1, 2013, Obama, speaking about Hollingsworth v. Perry, the U.S. Supreme Court case about Proposition 8, said "When the Supreme Court asks do you think that the California law, which doesn't provide any rationale for discriminating against same-sex couples other than just the notion that, well, they're same-sex couples—if the Supreme Court asks me or my attorney general or solicitor general, 'Do we think that meets constitutional muster?' I felt it was important for us to answer that question honestly. And the answer is no." The administration took the position that the Supreme Court should apply "heightened scrutiny" to California's ban—a standard under which legal experts say no state ban could survive.[117]

On August 7, 2013, Obama criticized Russia's anti-gay law.[118]

On December 26, 2013, President Obama signed the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2014 into law, which repealed the ban on consensual sodomy in the UCMJ.[119]

2014[]

On February 16, 2014, Obama criticized Uganda's anti-gay law.[120]

On February 28, 2014, Obama agreed with Governor Jan Brewer's veto of SB 1062.[121]

Obama included openly gay athletes in the February 2014 Olympic delegation, namely Brian Boitano and Billie Jean King (who was replaced by Caitlin Cahow, who was also openly gay.)[122][123] This was done in criticism of Russia's anti-gay law.[123]

On July 21, 2014, President Obama signed Executive Order 13672, adding "gender identity" to the categories protected against discrimination in hiring in the federal civilian workforce and both "sexual orientation" and gender identity" to the categories protected against discrimination in hiring and employment on the part of federal government contractors and sub-contractors.[124]

Obama was also criticized for meeting with the anti-gay Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni at a dinner with African heads of state in August 2014.[125]

Later in August 2014 Obama made a surprise video appearance at the opening ceremony of the 2014 Gay Games.[126][127]

2015[]

On February 10, 2015, David Axelrod's Believer: My Forty Years in Politics was published. In the book, Axelrod revealed that President Barack Obama lied about his opposition to same-sex marriage for religious reasons in 2008 United States presidential election. "I'm just not very good at bullshitting," Obama told Axelrod, after an event where he stated his opposition to same-sex marriage, according to the book.[128]

On June 26, 2015 the U.S. Supreme Court struck down all state bans on same-sex marriage, legalized it in all fifty states, and required states to honor out-of-state same-sex marriage licenses in the case Obergefell v. Hodges.

In 2015 the United States appointed Randy Berry as its first Special Envoy for the Human Rights of LGBT Persons.[129]

Also in 2015 the Obama administration announced it had opened a gender-neutral bathroom within the White House complex; the bathroom is in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, next door to the West Wing.[130]

Also in 2015, President Obama responded to a petition seeking to ban conversion therapy (inspired by the death of Leelah Alcorn) with a pledge to advocate for such a ban.[131]

Also in 2015, when President Obama declared May to be National Foster Care Month, he included words never before included in a White House proclamation about adoption, stating in part, "With so many children waiting for loving homes, it is important to ensure all qualified caregivers have the opportunity to serve as foster or adoptive parents, regardless of race, religion, sexual orientation, gender identity, or marital status. That is why we are working to break down the barriers that exist and investing in efforts to recruit more qualified parents for children in foster care." Thus it appears he is the first president to explicitly say gender identity should not prevent anyone from adopting or becoming a foster parent.[132]

On October 29, 2015, President Barack Obama endorsed Proposition 1.[133] Subsequently on November 10, 2015, President Barack Obama officially announced his support for the Equality Act of 2015.[134]

2016[]

In June 2016, President Obama dedicated the new Stonewall National Monument in Greenwich Village, Lower Manhattan, as the first U.S. National Monument to honor the LGBT rights movement.[135]

On October 20, President Obama endorsed Kate Brown as Governor of Oregon.[137] On November 8, Brown, who is bisexual, became the United States' first openly LGBT person elected Governor. She has also come out as a sexual assault survivor.[138] She assumed office in 2015 due to a resignation.[139] During her tenure as Governor before her election, she signed legislation to ban conversion therapy on minors.[140]

Presidential transition of Donald Trump[]

During the 2016 Republican National Convention Donald Trump said "As your president, I will do everything in my power to protect our LGBTQ citizens, from the violence and oppression of hateful foreign ideologies".[141] At a campaign rally on October 29, 2016, Trump held up a Rainbow Flag on stage upside down marked with "LGBTs for Trump".[142] On November 11, 2016, Trump appointed Peter Theil to the executive committee of his presidential transition team.[143] On November 13, 2016, during an interview with Lesley Stahl on 60 Minutes, Trump said that he was fine with the Obergefell v. Hodges Supreme Court decision and that it was irrelevant whether he supported same-sex marriage or not because the law was settled.[144][145] Trump's decisions as president have put into question the sincerity of his comments as a candidate.[146][147][148][149] On October 13, 2017, Trump became the first sitting president to address the Values Voter Summit, an annual conference sponsored by the Family Research Council, which is known for its anti-LGBT civil rights advocacy.[150][151]

2020[]

In 2020, the coronavirus pandemic in the United States led to cancellation of most pride parades across the United States during the traditional pride month of June. However, Brooklyn Liberation March, the largest transgender-rights demonstration in LGBTQ history, took place on June 14, 2020 stretching from Grand Army Plaza to Fort Greene, Brooklyn, focused on supporting Black transgender lives, drawing an estimated 15,000 to 20,000 participants.[152][153]

Bostock v. Clayton County, 590 U.S. ___ (2020), was a landmark Supreme Court case in which the Court ruled (on June 15, 2020) that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 protects employees against discrimination because of their sexual orientation or gender identity.[154][155]

Presidency of Joe Biden[]

2021[]

On 20 January 2021, Joe Biden took office as the 46th President of the United States. Pete Buttigieg (openly gay, Democrats and former the Mayor of South Bend) took office as the 19th Secretary of Transportation on 3 February 2021.[156] His nomination was confirmed on February 2, 2021 by a vote of 86–13, making him the first openly LGBT Cabinet member in U.S. history.[a][157] Nominated at age 38, he is also the youngest Cabinet secretary in the Biden administration and the youngest person ever to serve as Secretary of Transportation.[158][159]

Historiography[]

Scholars of U.S. LGBT history

|

|

By state[]

- LGBT history in New York

- LGBT history in California

- LGBT history in Florida

- LGBT history in Illinois

- LGBT history in Texas

- LGBT history in Michigan

- LGBT history in Louisiana

- LGBT history in Hawaii

- LGBT history in North Dakota

- LGBT history in South Dakota

See also[]

- Bisexuality in the United States

- History of gay men in the United States

- History of lesbianism in the United States

- History of transgender people in the United States

- LGBT demographics of the United States

- LGBT historic places in the United States

- History of homosexuality in American film

- Biphobia

- Homophobia

- Lesbophobia

- List of LGBT actions in the United States prior to the Stonewall riots

Notes[]

References[]

- ^ Rosenberg, Eli (June 24, 2016). "Stonewall Inn Named National Monument, a First for the Gay Rights Movement". The New York Times. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- ^ "Workforce Diversity The Stonewall Inn, National Historic Landmark National Register Number: 99000562". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- ^ Hayasaki, Erika (May 18, 2007). "A new generation in the West Village". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- ^ Henry, C. J. (2013). "Preface". Advances in Food and Nutrition Research. 69: xi. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-410540-9.09988-9. ISSN 1043-4526. PMID 23522798.

- ^ Walker, Harron (August 16, 2019). "Here's Every State That Requires Schools to Teach LGBTQ+ History". Out Magazine. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "The History of Sodomy Laws in the United States - Introduction". www.glapn.org.

- ^ Webster, Noah (1828). Webster's American Dictionary of the English Language. Webster.

- ^ Webster, Noah (1828). Webster's American Dictionary of the English Language. Webster.

- ^ Webster, Noah (1828). Webster's American Dictionary of the English Language. Webster.

- ^ Webster, Noah (1828). Webster's American Dictionary of the English Language. Webster.

- ^ Webster, Noah (1828). Webster's American Dictionary of the English Language. Webster.

- ^ Webster, Noah (1828). Webster's American Dictionary of the English Language. Webster.

- ^ Webster, Noah (1828). Webster's American Dictionary of the English Language. Webster.

- ^ Webster, Noah (1828). Webster's American Dictionary of the English Language. Webster.

- ^ Webster, Noah (1828). Webster's American Dictionary of the English Language. Webster.

- ^ Webster, Noah (1828). Webster's American Dictionary of the English Language. Webster.

- ^ Herndon, William H., Herndon's Lincoln: The True Story of a Great Life. Chicago: Clarke, Belford. 1889.

- ^ Monroe, Irene. "America's Gay Confederate and Union Soldiers". LA Progressive. LA Progressive. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ Walt Whitman: A Study. 1893. New York: Dutton, 1906.

- ^ Whitman, Walt. Selected Letters of Walt Whitman. Ed. Edwin Haviland Miller. Iowa City: U of Iowa P, 1990.

- ^ Hoyt, Edwin P. (1974). Horatio's Boys. Chilton Book Company. ISBN 0-8019-5966-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The improbable, 200-year-old story of one of America's first same-sex ‘marriages’". The Washington Post, March 20, 2015.

- ^ "Gold Rush Gays". Bay Area Reporter, November 20, 2014.

- ^ Brockwell, Gillian (2019-06-20). "A gay first lady? Yes, we've already had one, and here are her love letters". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2019-06-21.

- ^ Lillian Faderman, Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in Twentieth-Century America, Penguin Books Ltd, 1991, page 32

- ^ Solly, Meilan (2019-09-21). "New Book Chronicles First Lady Rose Cleveland's Love Affair With Evangeline Simpson Whipple". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2019-06-21.

- ^ Evangeline Marrs Simpson Whipple (1930-09-01). "Evangeline Whipple". In honor of the people. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

- ^ Joseph, Channing Gerard (31 January 2020). "The First Drag Queen Was a Former Slave". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ Heloise Wood (July 9, 2018). "'Extraordinary' tale of 'first' drag queen to Picador". The Bookseller. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- ^ Norton, Rictor (12 February 2005). "The Suppression of Lesbian and Gay History".

- ^ Prime-Stevenson, Edward 'Xavier Mayne.' The Intersexes. Privately printed. 1908. <https://en.m.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Intersexes:_A_History_of_Similisexualism_as_a_Problem_in_Social_Life>

- ^ Bullough, Vern (17 April 2005). "Because the Past is the Present, and the Future too". History News Network.

- ^ Julian Eltinge. Billy Rose Theatre Division. New York Public Library. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/9d0c6e52-c763-e146-e040-e00a18064043

- ^ October 1, 1972 "The Billings Gazette." from Billings, Montana · Page 46

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Masculine Women, Feminine Men." Queer Music Heritage. Retrieved 16 July. 2017. <http://queermusicheritage.com/MWFM.html>

- ^ "Out Of The Past". www.pbs.org.

- ^ "George Hannah - 'The Boy in the Boat.'" The Pop-Up Museum of Queer History. Retrieved 16 July. 2017. <http://queermuseum.tumblr.com/post/33891283624/queer-history-month-day-19-george-hannah-the>

- ^ Arnold, Kokomo. "Sissy Man Blues". Decca 7050. January 15, 1935. Retrieved 16 July. 2017.

- ^ " Sissy Man Blues." Queer Music Heritage. Retrieved 16 July. 2017

- ^ Chauncey, George (1994). Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890–1940. New York: Basic Books.

- ^ Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, (1948) ISBN 978-0-253-33412-1.

- ^ Tropiano, Stephen (2002). The Prime Time Closet: A History of Gays and Lesbians on TV. New York, Applause Theatre and Cinema Books. ISBN 1-55783-557-8.

- ^ One, Inc. v. Olesen, 335 U.S. 371 (1958), reversing the Ninth Circuit's decision per curiam, citing Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476; full-text of opinion.

- ^ "Laws of Illinois." 1961, page 1983, enacted July 28, 1961, effective Jan. 1, 1962.

- ^ Paola Bacchetta. "Dyketactics! Notes Towards an Un-silencing." In Smash the Church, Smash the State: The Early Years of Gay Liberation, edited by Tommi Avicolli Mecca, 218-231. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2009.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-06-05. Retrieved 2013-08-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Cone, Russ (January 8, 1978). "Feinstein Board President", The San Francisco Examiner, p. 1.

- ^ Turner, Wallace (November 28, 1978). "Suspect Sought Job", The New York Times, p. 1.

- ^ Cloud, John (June 14, 1999). "Harvey Milk", Time. Retrieved on August 4, 2013.

- ^ 40 Heroes Archived 2009-01-25 at the Wayback Machine, The Advocate (September 25, 2007), Issue 993. Retrieved on August 4, 2013.

- ^ Ghaziani, Amin. 2008. "The Dividends of Dissent: How Conflict and Culture Work in Lesbian and Gay Marches on Washington". The University of Chicago Press.

- ^ Thomas, Jo (October 15, 1979), "Estimated 75,000 persons parade through Washington, DC, in homosexual rights march. Urge passage of legislation to protect rights of homosexuals", The New York Times Abstracts, p. 14

- ^ "Percy & Glover 2005". Archived from the original on June 21, 2008.

- ^ Crimp, Douglas. AIDS Demographics. Bay Press, 1990. (Comprehensive early history of ACT UP, discussion of the various signs and symbols used by ACT UP).

- ^ Connecticut Public Acts 1969, page 1554, Public Act No. 828, enacted July 8, 1969, effective Oct. 1, 1971.

- ^ Colorado Laws 1971, page 388, ch. 121, enacted June 2, 1971, effective July 1, 1972.

- ^ General Laws of Oregon 1971, page 1873, ch. 743, enacted July 2, 1971, effective Jan. 1, 1972.

- ^ Laws of Delaware, Vol. 58, ch. 497, enacted July 6, 1972, effective Apr. 1, 1973

- ^ 134 Laws of Ohio, page 1866, enacted Dec. 22, 1972, effective Jan. 1, 1974.

- ^ 318 N.E.2d 478, decided Nov. 1, 1974.

- ^ Laws of North Dakota 1973, ch. 117, adopted Mar. 28, 1973, effective July 1, 1975.

- ^ New Mexico Laws of 1975, ch. 109, enacted Apr. 3, 1975, effective June 20, 1975.

- ^ New Hampshire Laws 1975, page 273, ch. 302, enacted June 7, 1975, effective Aug. 6, 1975.

- ^ Statutes and Amendments to the Codes of California 1975, page 131, ch. 71, enacted May 12, 1975.

- ^ Laws of West Virginia 1976, page 241, ch. 43, enacted Mar. 11, 1976, effective June 11, 1976.

- ^ 242 N.W.2d 348, decided May 19, 1976.

- ^ Maine Public Laws 1975, page 1273, ch. 499, enacted June 3, 1975, effective May 1, 1976.

- ^ Acts 1976 Indiana, page 718, Public Law No. 148, enacted Feb. 25,1976, effective July 1, 1977.

- ^ Laws of South Dakota 1976, page 227, ch. 158, enacted Feb. 27, 1976, effective Apr. 1, 1977.

- ^ Laws of Wyoming 1977, page 228, ch. 70, enacted Feb. 24, 1977, effective May 27, 1977.

- ^ Laws of Nebraska 1977, page 88, enacted June 1, 1977, effective July 1, 1978. The law was enacted by overriding the veto of the Governor. The override vote in the state's unicameral legislature was 32-15, with not a single vote to spare, two-thirds being necessary.

- ^ Laws of Washington 1975 1st Ex. Sess., page 817, ch. 260, enacted June 27, 1975, effective July 1, 1976.

- ^ Jump up to: a b 400 N.Y.S.2d 455, decided Dec. 5, 1977.

- ^ Laws of Wisconsin 1983, Vol. 1, page 37, ch. 17, enacted May 5, 1983, published May 11, 1983.

- ^ 842 S.W.2d 487, decided Sep. 24, 1992. Rehearing denied Jan. 21, 1993. The case dragged on for some six years because of a dispute as to whether Kentucky could appeal the dismissal of charges against Wasson. An appellate court decided that it could, which sent the case back to the second level of court for a decision. See Commonwealth v. Wasson, 785 S.W.2d 67, decided Jan. 12, 1990. The Kentucky Supreme Court's Wasson decision was the lead story in the Winter 1992-1993 issue of Civil Liberties.

- ^ 849 P.2d 336, decided Mar. 24, 1993

- ^ 926 S.W. 2d 250, decided Jan. 26, 1996.

- ^ 942 P.2d 112, decided July 2, 1997.

- ^ Public Laws of Rhode Island 1998, ch. 24, enacted June 5, 1998.

- ^ es:Omar Mateen

- ^ "Ex-Wife Says Orlando Shooter Might Have Hidden Homosexuality". Time.

- ^ Weiner, Rachel (2010-03-18). "Hate Crimes Bill Signed Into Law 11 Years After Matthew Shepard's Death". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2019-01-30.

- ^ Pleming, Sue (March 18, 2009). "In turnaround, U.S. signs U.N. gay rights document". Reuters. Retrieved November 9, 2012.

- ^ "The U. S. Government". ThoughtCo.

- ^ "Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Pride Month, 2009". whitehouse.gov. Retrieved June 29, 2014 – via National Archives.

- ^ "Presidential Proclamation--Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Pride Month". whitehouse.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-02-16 – via National Archives.

- ^ "Presidential Proclamation-Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Pride Month | The White House". whitehouse.gov. May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 29, 2014 – via National Archives.

- ^ "Presidential Proclamation: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Pride Month, 2012". whitehouse.gov. June 1, 2012 – via National Archives.

- ^ "Presidential Proclamation - Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Pride Month, 2013". whitehouse.gov. May 31, 2013. Retrieved June 29, 2014 – via National Archives.

- ^ "Obama proclaims June LGBT Pride Month". Metro Weekly. May 30, 2014. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ "Obama issues Presidential Proclamation declaring June LGBT Pride Month – LGBTQ Nation". Lgbtqnation.com. 2015-05-29. Retrieved 2015-06-04.

- ^ "Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies on Federal Benefits and Non-Discrimination, 6-17-09". whitehouse.gov. Archived from the original on January 20, 2017. Retrieved April 6, 2016 – via National Archives.

- ^ Weiner, Rachel (October 28, 2009). "Hate Crimes Bill Signed Into Law 11 Years After Matthew Shepard's Death". Huffington Post.

- ^ "Sharon Lubinski: Senate Confirms First Openly Gay US Marshal". Huffington Post. December 28, 2009.

- ^ Tapper, Jake (January 4, 2010). "President Obama Names Transgender Appointee to Commerce Department". ABC News. Archived from the original on January 7, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ^ "Obama's New Queer Appointee Amanda Simpson Brings Some 'T' to the Administration". Queerty.com. December 31, 2009. Archived from the original on January 19, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ^ "Obama Hires Trans Woman Amanda Simpson". National Center for Transgender Equality. December 31, 2009. Archived from the original on January 4, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ^ Hananel, Sam (October 26, 2010). "Obama has appointed most U.S. gay officials". Washington Times. Retrieved November 9, 2012.

- ^ "Obama Widens Medical Rights for Gay Partners". The New York Times. April 16, 2010.

- ^ "Obama Expands Family Medical Leave Act to Cover Gay Employees". Fox News. June 22, 2010.

- ^ "Obama signs bill repealing 'don't ask, don't tell' policy". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. December 22, 2010. Archived from the original on December 26, 2010. Retrieved December 22, 2010.

- ^ "President Obama Instructs Justice Department to Stop Defending Defense of Marriage Act calls Clinton-Signed Law "Unconstitutional"". Abcnews.go.com. February 23, 2011. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "U.N. Gay Rights Protection Resolution Passes, Hailed As 'Historic Moment'". The Huffington Post. June 17, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ "Fewer Youths to Be Deported in New Policy". The New York Times. August 19, 2011. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- ^ Tate, Curtis. "Pentagon says chaplains may perform gay weddings". McClatchy. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- ^ "U.S. to Aid Gay Rights Abroad, Obama and Clinton Say". The New York Times. December 7, 2011. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- ^ Johnson, Luke (April 9, 2012). "Obama Opposes Minnesota Anti-Gay Marriage Constitutional Amendment". The Huffington Post. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ "LGBT Prison Employees to Get Representation - Advocate.com". Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- ^ Stein, Sam (May 9, 2012). "Obama Backs Gay Marriage". Huffington Post.

- ^ yvonna. "Home | Gay-Straight Alliance Network". Gsanetwork.org. Retrieved October 9, 2012.

- ^ Raghavan, Gautam (January 25, 2012). "A Special Message on National Gay-Straight Alliance Day | The White House". whitehouse.gov. Retrieved October 9, 2012 – via National Archives.

- ^ Adams, Jamiah (May 27, 2011). "HRC Endorses President Obama for 2012". Democrats.org. Archived from the original on October 4, 2012. Retrieved October 9, 2012.

- ^ "2012 Endorsements". Votesmart.org. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ "Gay Troops Discharged Under DADT To Receive Full Severance Pay". On Top Magazine.

- ^ Robillard, Kevin (January 21, 2013). "First inaugural use of the word 'gay'". Politico. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- ^ Michelson, Noah (January 21, 2013). "Obama Inauguration Speech Makes History With Mention Of Gay Rights Struggle, Stonewall Uprising". Huffington Post. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- ^ Wolf, Richard (March 1, 2013). "Obama: I would rule against all gay marriage bans". USA Today.

- ^ Parsons, Christi (7 August 2013). "Obama criticizes Russia's new anti-gay law in Leno interview". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ Deutch, Theodore. "H.R. 3304: National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2014". Govtrack.us. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ "Obama Condemns Uganda's Tough Antigay Measure". The New York Times. February 17, 2014.

- ^ "Carney: Brewer 'did the right thing' by vetoing anti-gay bill". Washington Blade: Gay News, Politics, LGBT Rights. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- ^ "Obama includes openly gay athletes in 2014 Olympic delegation". CBS News. December 17, 2013. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "U.S. delegation delivers strong message in Sochi". USA Today. February 7, 2014. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ "Executive Order -- Further Amendments to Executive Order 11478, Equal Employment Opportunity in the Federal Government, and Executive Order 11246, Equal Employment Opportunity". whitehouse.gov. Office of the Press Secretary. July 21, 2014. Retrieved July 21, 2014 – via National Archives.

- ^ "Uganda's Museveni meets with Obama days after repeal of anti-gay law". Gay Star News. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ "President Obama makes video appearance at Gay Games". WKYC. August 9, 2014. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ "Obama Makes Surprise Video Appearance at Gay Games Opening Ceremony: WATCH". Towleroad: A Site With Homosexual Tendencies. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ Miller, Zeke J. "David Axelrod: Barack Obama Misled Nation On Gay Marriage In 2008". TIME.com. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- ^ Peralta, Eyder. "U.S. Appoints First-Ever Special Envoy For LGBT Rights : The Two-Way". NPR. Retrieved 2015-02-24.

- ^ White House complex now has a gender-neutral bathroom - CNN.com. Edition.cnn.com (2008-10-29). Retrieved on 2015-04-10.

- ^ Saker, Anne (2015-04-09). "Leelah's death moves Obama to respond". Cincinnati.com. Retrieved 2015-04-10.

- ^ Ennis, Dawn. "Obama Calls for End to Discriminatory Parenting Laws". Advocate.com. Retrieved 2015-05-04.

- ^ "Obama Administration Affirms Support for LGBT Non-Discrimination & HERO". Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- ^ Eilperin, Juliet (November 10, 2015). "Obama supports altering Civil Rights Act to ban LGBT discrimination". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rosenberg, Eli (June 24, 2016). "Stonewall Inn Named National Monument, a First for the Gay Rights Movement". The New York Times. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ^ "Workforce Diversity The Stonewall Inn, National Historic Landmark National Register Number: 99000562". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved May 1, 2011.

- ^ Johnson, Chris (October 20, 2016). "President Obama endorses Oregon Gov. Kate Brown". KGW.

- ^ "Bisexual Governor Kate Brown Talks Openly About Surviving Domestic Violence, Shuts Down Opponent's Ignorance". Autostraddle. October 6, 2016.

- ^ "Kate Brown becomes first openly LGBT person elected governor". November 8, 2016.

- ^ Brydum, Sunnivie (May 19, 2015). "Oregon's Bisexual Gov. Bans Conversion Therapy". Advocate.

- ^ "Trump: "I Will Protect Our LGBTQ Citizens'". NBC News. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- ^ http://www.washingtontimes.com, The Washington Times. "Donald Trump holds high the flag for gay equality". The Washington Times. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- ^ Lecher, Colin (November 11, 2016). "Peter Thiel is joining Donald Trump's transition team". The Verge.

- ^ "President-Elect Trump Says Same-Sex Marriage Is 'Settled' Law". ABC News. 2016-11-14. Retrieved 2017-05-16.

- ^ "Donald Trump says the law is settled on gay marriage but not on abortion" – via The Economist.

- ^ "Trump escalates clash with LGBT community". Politico. Retrieved 2017-08-17.

- ^ "The first 100 days in LGBT rights". CNN. Retrieved 2017-08-17.

- ^ "Everything Donald Trump Has Said About the LGBTQ Community as President Announces Trans Military Ban". People. Retrieved 2017-08-17.

- ^ S.M. (September 8, 2017). "The Department of Justice backs a baker who refused to make a gay wedding cake". The Economist. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ Oppenheim, Maya (October 13, 2017). "Donald Trump to become first president to speak at anti-LGBT hate group's annual summit". The Independent. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

- ^ Folley, Arris (October 13, 2017). "Anti-LGBT pamphlets handed out at Values Voter Summit Trump spoke at". AOL. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

- ^ Anushka Patil (June 15, 2020). "How a March for Black Trans Lives Became a Huge Event". The New York Times. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ Shannon Keating (June 6, 2020). "Corporate Pride Events Can't Happen This Year. Let's Keep It That Way". Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ Bostock v. Clayton County, No. 17-1618, 590 U.S. ___ (2020).

- ^ Supreme Court Ruling 2020-06-15 (pages 1 – 33 in the linked document)

- ^ Merica, Dan (December 15, 2020). "Joe Biden picks Pete Buttigieg to be transportation secretary". CNN. Retrieved December 15, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hebb, Gina (2 February 2021). "Pete Buttigieg makes history as 1st openly gay Cabinet member confirmed by Senate". ABC News. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ D. Shear, Michael; Kaplan, Thomas (16 December 2020). "Buttigieg Recalls Discrimination Against Gay People, as Biden Celebrates Cabinet's Diversity". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Verma, Pranshu (2 February 2021). "Pete Buttigieg Is Confirmed as Biden's Transportation Secretary". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

External links[]

- Timeline: Milestones in the American Gay Rights Movement PBS

Media related to LGBT history in the United States at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to LGBT history in the United States at Wikimedia Commons

- LGBT history in the United States

- LGBT history by country