LGBT rights in Oklahoma

| |

| Status | Legal statewide since 2003 (Lawrence v. Texas) |

| Gender identity | Transgender people allowed to change legal gender |

| Discrimination protections | Protections in employment; further protections in Norman |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships | Same-sex marriage since 2014 |

| Adoption | Same-sex couples allowed to adopt |

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) persons in the U.S. state of Oklahoma enjoy most of the rights available to non-LGBT residents. Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Oklahoma, and both same-sex marriage and adoption by same-sex couples have been permitted since October 2014. State statutes do not prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity; however, the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Bostock v. Clayton County established that employment discrimination against LGBT people is illegal.[1] This practice may still continue, as Oklahoma is an at-will employment state and it is still legal to fire an employee without requiring the employer to disclose any reason.

History and legality of same-sex sexual activity[]

Prior to European settlement, several Native American tribes inhabited the region. These peoples had perceptions towards gender and sexuality which differed significantly to that of the Western world. Tribes who were forcibly moved to Oklahoma also have/had such perceptions. Male-bodied individuals who act, behave and dress as women are known as haxu'xan among the Arapaho, he'émáné'e among the Cheyenne, kúsaat among the Pawnee people, and m'netokwe among the Potawatomi, whereas female-bodied individuals who act and live as male are referred to as hetanémáné'e among the Cheyenne. These individuals, nowadays also called "two-spirit", were traditionally regarded as supernatural and blessed by the spirits. In the Omaha-Ponca language, spoken by the Ponca and Omaha peoples, the term mix'uga refers to intersex or transgender people. Literally, the term means "instructed by the moon". Similar terms exist in the Chiwere language, historically spoken by the Missouria, Otoe and Iowa peoples, where it is mixo'ge, and in the now-extinct Kansa language where it is míⁿxoge.

Upon its creation in 1890, the Oklahoma Territory passed a criminal code punishing sodomy ("crime against nature"), whether heterosexual or homosexual, with up to 10 years' imprisonment. The crime was complete upon penetration only. The law applied to consensual adults and married couples as well. The first recorded sodomy case occurred in 1917, when a judge ruled in Ex Parte DeFord that fellatio (oral sex) violated the sodomy statute. Likewise, in the 1935 case of Roberts v. State, the Criminal Court of Appeals held that cunnilingus was a violation of the law. In 1943, in LeFavour v. State, the same court rejected contentions that the sodomy law applied only to people of the same sex, confirming that it applied universally regardless of sex or sexual orientation.[2]

In 1933, the Oklahoma Legislature passed a law providing for the possible sterilization of "habitual criminals", including those convicted under the sodomy law. The law was challenged, but upheld by the Oklahoma Supreme Court in 1941 by a vote of 5–4. The U.S. Supreme Court unanimously struck down the law in 1942, in the case of Skinner v. Oklahoma. The landmark decision effectively ended the sterilization of criminals in the United States; no new sterilization laws were passed in any state and the existing ones were repealed or fell into disuse. The law was ultimately repealed in 1983, almost 40 years after having been invalidated.[2]

One of the few court cases to deal with lesbian activity occurred in 1971, in Warner et al v. State. In this case, a married couple were convicted of forcing an Oklahoma City woman to engage in oral sex with each of them. The Court of Criminal Appeals specifically noted that lesbian activity was a violation of the sodomy statute. In 1973, the Court of Criminal Appeals, in Canfield v. State, voted 2–1 to uphold the conviction and sentence of 15 years in jail of Kenneth Canfield for consensual sodomy. The court rejected arguments that the law was an unconstitutional invasion of privacy. In Post v. State (1986), the court ruled that the sodomy law could not be applied to private, consensual adult heterosexual activity. The court did not address homosexual activity in its ruling.[2]

In 1997, the Oklahoma Legislature revised parts of the sodomy statute, reducing the penalty to 2 years' imprisonment, a fine of 1,000 U.S. dollars or both. The law was short-lived; in 1999, a new law made same-sex sodomy punishable by up to 20 years in prison.[2]

Same-sex sexual activity has been legal in Oklahoma since 2003, when the United States Supreme Court struck down all state sodomy laws with its ruling in Lawrence v. Texas.[3][4]

Recognition of same-sex relationships[]

In April 2004, the Oklahoma Senate, by a vote of 38 to 7, and the Oklahoma House of Representatives, by a vote of 92 to 4, approved a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage. On November 2, 2004, Oklahoma voters approved Oklahoma Question 711, a constitutional amendment which banned same-sex marriage and any "legal incidents thereof be conferred upon unmarried couples or groups".[5][6][7] On January 14, 2014, Judge Terence C. Kern, of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Oklahoma, declared Question 711 unconstitutional. The case, Bishop v. United States (formerly Bishop v. Oklahoma), was stayed pending appeal.[8] A 3-judge panel of the Tenth Circuit heard oral arguments in Bishop on April 17, 2014, and upheld the district court's decision on July 18.[9]

On October 6, 2014, the United States Supreme Court turned down Oklahoma's appeal which reinstates the district court's ruling that the state's ban on same-sex marriage is unconstitutional. Following the court's rejection of the appeal, the Oklahoma County Court Clerk's Office and others across the state started issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples.[10]

Adoption and parenting[]

Oklahoma permits adoption by a couple or an unmarried adult without regard to sexual orientation.[11] Lesbian couples can access fertility treatments and in vitro fertilization. State law recognizes the non-genetic, non-gestational mother as a legal parent to a child born via donor insemination, but only if the parents are married.[12] In addition, while there are no specific surrogacy laws in Oklahoma, the courts have ruled that the practice is legal and surrogacy contracts can be recognized as legally valid. Both gestational and traditional contracts are recognized, though the latter may result in potential legal conflicts and more litigation than the former. The state treats different-sex and same-sex couples equally under the same terms and conditions.[13]

In August 2007, the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals in the case of Finstuen v. Crutcher ordered Oklahoma to issue a revised birth certificate showing both adoptive parents to a child born in Oklahoma who had been adopted by a same-sex couple married elsewhere.[14]

Oklahoma law allows adoption agencies to choose not to place children in certain homes if it "would violate the agency's written religious or moral convictions or policies."[15]

Discrimination protections[]

Oklahoma statutes do not address discrimination based on gender identity or sexual orientation.[16]

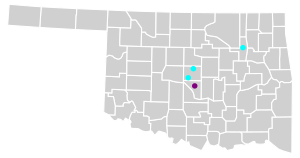

The city of Norman has a nondiscrimination policy that prohibits discrimination in employment, housing and public accommodations on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity,[17][18] while the cities of Edmond,[19] Oklahoma City and Tulsa have nondiscrimination policies that prohibit discrimination in public employment (i.e. city employees only) on account of sexual orientation.[20][21]

Bostock v. Clayton County[]

On June 15, 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Bostock v. Clayton County, consolidated with Altitude Express, Inc. v. Zarda, and R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes Inc. v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission that discrimination in the workplace on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity is discrimination on the basis of sex, and Title VII therefore protects LGBT employees from discrimination.[22][23][24]

Conversion therapy[]

In Norman city conversion therapy is banned since July 2021, the first city within Oklahoma to ban conversion therapy.[25]

Hate crime law[]

State law does not address hate crimes based on gender identity or sexual orientation.[26] However, since the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act was signed into law in October 2009, federal law has provided additional penalties for crimes motivated by the victim's actual or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity. Hate crimes against LGBT people can be prosecuted in federal court.

Transgender rights[]

The Office of Vital Records will alter the gender marker on the birth certificate of a transgender person upon receipt of a court order and a completed "Birth Certificate Request Form".[27] Sex reassignment surgery, sterilization and other medical interventions are not officially required, though the applicant may undergo such procedures if they wish. However, if wanting to change the gender marker on a driver's license, the applicant will have to submit to the Department of Public Safety a notarized statement from a physician confirming that they have undergone "permanent and irreversible" sex change surgery.

In 2018, a local school in Achille had to shut down for a few days due to safety concerns after a 12-year-old transgender student received death threats and threats of mutilation, whipping and castration by her classmates' parents.[28]

Freedom of expression[]

No promo homo law[]

Oklahoma has a "no promo homo law" in place that forbids the "promotion of homosexuality" in schools and instructs HIV-related education to teach students that not "engaging in homosexual activity" prevents the spread of the HIV virus.[29]

Diversity training ban[]

In April 2021, the Oklahoma Legislature passed a bill legally banning any diversity training. The Governor of Oklahoma Kevin Stitt signed the bill into law effective immediately.[30][31]

National Guard[]

Proposed legislation to institute in the Oklahoma National Guard a local version of "Don't ask, don't tell" (DADT), the federal policy that formerly prohibited gays, lesbians and bisexuals from serving openly in the U.S. military, was proposed in January 2012 and withdrawn in February.[32][33]

Following the U.S. Supreme Court decision in United States V. Windsor in June 2013 invalidating Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act,[34] the U.S. Department of Defense issued directives requiring state units of the National Guard to enroll the same-sex spouses of guard members in federal benefit programs. Guard officials in Oklahoma enrolled some same-sex couples until September 5, 2013, when Governor Fallin ordered an end to the practice.[35] Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel on October 31 said he would insist on compliance.[36] On November 6, Fallin announced that members of the Oklahoma National Guard could apply for benefits for same-sex partners at federally owned ONG facilities, where most staffers are federal employees, and at federal military installations.[37] When DoD officials objected to that plan, Fallin ordered that all married couples, opposite-sex or same-sex, would be required to have benefits requests processed at those facilities.[38]

Public opinion[]

Recent polls have found that support for same-sex marriage and LGBT rights is increasing and opposition is decreasing.

A 2017 Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) poll found that 53% of Oklahomans supported same-sex marriage, while 36% were opposed. 11% were undecided. Additionally, 64% supported an anti-discrimination law covering sexual orientation and gender identity. 25% were against. The PRRI also found that 51% were against allowing public businesses to refuse to serve LGBT people due to religious beliefs, while 39% supported such religiously-based refusals.[39]

| Poll source | Date(s) administered |

Sample size |

Margin of error |

% support | % opposition | % no opinion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Religion Research Institute | January 2-December 30, 2019 | 573 | ? | 63% | 27% | 10% |

| Public Religion Research Institute | January 3-December 30, 2018 | 652 | ? | 62% | 29% | 9% |

| Public Religion Research Institute | April 5-December 23, 2017 | 794 | ? | 64% | 25% | 11% |

| Public Religion Research Institute | April 29, 2015-January 7, 2016 | 1,038 | ? | 60% | 36% | 4% |

Summary table[]

| Same-sex sexual activity legal | |

| Equal age of consent | |

| Anti-discrimination laws for sexual orientation | |

| Anti-discrimination laws for gender identity | |

| Same-sex marriages | |

| Stepchild and joint adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Lesbian, gay and bisexual people allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Transgender people allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Intersex people allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Conversion therapy banned on minors | |

| Right to change legal gender | |

| Access to IVF for lesbian couples | |

| Surrogacy arrangements legal for gay male couples | |

| MSMs allowed to donate blood |

See also[]

- Cimarron Alliance Foundation

- National Gay Task Force v. Board of Education

- No promo homo laws

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b The city of Norman provides further protections, including in housing and public accommodations.

References[]

- ^ Rodriguez, Laura; Gatlin, Donald. "Approximately 62,000 LGBT Workers in Oklahoma Lack Statewide Protections against Ongoing Employment Discrimination". The Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d The History of Sodomy Laws in the United States - Oklahoma

- ^ "Oklahoma Sodomy Law". Human Rights Campaign. June 26, 2003. Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- ^ Legal Citation 539 U.S. 558 (2003). Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ^ "Oklahoma Marriage/Relationship Recognition Law". Hrc.org. March 16, 2007. Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- ^ CNN: Ballot Measures, accessed May 15, 2011

- ^ "US judge strikes down Oklahoma gay marriage ban as 'arbitrary, irrational' (+video)". Csmonitor.com. January 14, 2014. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ Federal lawsuit renewed against Oklahoma's constitutional ban of same-sex marriage Accessed 11 December 2010

- ^ Associated Press (August 8, 2014). "Oklahoma same-sex marriages ruled constitutional for second time". The Guardian. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ Lowry, Lacie (October 6, 2014). "Same-Sex Marriages Legal, Underway In Oklahoma". News9.com. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ Human Rights Campaign: Oklahoma Adoption Law Archived July 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, accessed May 15, 2011

- ^ "Oklahoma's equality profile". Movement Advancement Project.

- ^ "What You Need to Know About Surrogacy in Oklahoma". American Surrogacy.

- ^ Finstuen v. Crutcher (10th Cir. 2007), accessed July 11, 2011

- ^ Fortin, Jacey (May 12, 2018). "Oklahoma Passes Adoption Law That L.G.B.T. Groups Call Discriminatory". The New York Times.

- ^ Human Rights Campaign: Oklahoma Non-Discrimination Law Archived July 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, accessed May 15, 2011

- ^ Norman City Council affirms LGBT rights

- ^ "Municipal Equality Index" (PDF). Human Rights Campaign. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ MEI 2017: See Your City’s Score

- ^ Bryan, Emory (June 18, 2010). "Tulsa City Council Approves Sexual Orientation Policy; Rejects Immigration Ordinance". News on 6. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- ^ Kimball, Michael (November 16, 2011). "Oklahoma City Council passes sexual orientation measure". The Oklahoman. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- ^ Biskupic, Joan (June 16, 2020). "Two conservative justices joined decision expanding LGBTQ rights". CNN.

- ^ "US Supreme Court backs protection for LGBT workers". BBC News. June 15, 2020.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (June 15, 2020). "Civil Rights Law Protects Gay and Transgender Workers, Supreme Court Rules". The New York Times.

- ^ [1]

- ^ "Oklahoma Hate Crimes Law". Human Rights Campaign. Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- ^ Oklahoma, National Center for Transgender Equality

- ^ "Transgender Girl, 12, Is Violently Threatened After Facebook Post by Classmate's Parent". The New York Times. August 15, 2018.

- ^ "State Anti-LGBT Curriculum Laws". Lambda Legal.

- ^ [2]

- ^ [3]

- ^ "Bill Would Reintroduce DADT to Oklahoma Guard". Military.com. January 10, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ^ "DADT Bill Apparently Shelved in Oklahoma House". Military.com. February 21, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ^ legal citation as 570 U.S.___ (2013)

- ^ "Oklahoma Gov. Mary Fallin tells National Guard to deny same-sex benefits". New York Daily News. September 18, 2013. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ Johnson, Chris (October 31, 2013). "Hagel to direct nat'l guards to offer same-sex benefits". Washington Blade. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ Allen, Silas (November 7, 2013). "Oklahoma National Guard will process same-sex spouse benefits at a few federal facilities". NewsOK. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ Mills, Russell (November 20, 2013). "Fallin: OK will no longer process benefits for National Guard couples". KRMG. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ^ PRRI: American Values Atlas 2017

- ^ Baldor, Lolita; Miller, Zeke (January 25, 2021). "Biden reverses Trump ban on transgender people in military". Associated Press.

- ^ "Medical Conditions That Can Keep You From Joining the Military". Military.com.

- ^ [4]

- ^ McNamara, Audrey (April 2, 2020). "FDA eases blood donation requirements for gay men amid "urgent" shortage". CBS News.

External links[]

- LGBT in Oklahoma

- LGBT rights in the United States by state

- Oklahoma law

- Politics of Oklahoma