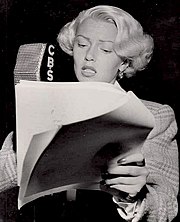

Lana Turner

Lana Turner | |

|---|---|

Turner in the 1940s | |

| Born | Julia Jean Turner February 8, 1921 Wallace, Idaho, U.S. |

| Died | June 29, 1995 (aged 74) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Occupation | Actress |

| Years active | 1937–1985 |

| Height | 5 ft 3 in (160 cm) |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | Cheryl Crane |

| Awards | Full list |

| Signature | |

| |

Lana Turner (/ˈlɑːnə/;[a] born Julia Jean Turner; February 8, 1921 – June 29, 1995) was an American actress. Over the course of her nearly 50-year career, she achieved fame as both a pin-up model and a film actress, as well as for her highly publicized personal life. In the mid-1940s, she was one of the highest-paid actresses in the United States, and one of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's (MGM) biggest stars, with her films earning more than $50 million for the studio during her 18-year contract with them. Turner is frequently cited as a popular culture icon of Hollywood glamour and a screen legend of classical Hollywood cinema.[4]

Born to working-class parents in northern Idaho, Turner spent her childhood there before her family relocated to San Francisco. In 1936, when Turner was 15, she was discovered while purchasing a soda at the Top Hat Malt Shop in Hollywood. At the age of 16, she was signed to a personal contract by Warner Bros. director Mervyn LeRoy, who took her with him when he transferred to MGM in 1938. She soon attracted attention by playing the role of a murder victim in her film debut, LeRoy's They Won't Forget (1937), and she later moved into supporting roles, often appearing as an ingénue.

During the early 1940s, Turner established herself as a leading lady and one of MGM's top stars, appearing in such films as the film noir Johnny Eager (1941); the musical Ziegfeld Girl (1941); the horror film Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1941); and the romantic war drama Somewhere I'll Find You (1942), one of several films in which she starred opposite Clark Gable. Turner's reputation as a glamorous femme fatale was enhanced by her critically acclaimed performance in the noir The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), a role which established her as a serious dramatic actress. Her popularity continued through the 1950s in dramas such as The Bad and the Beautiful (1952) and Peyton Place (1957), the latter for which she was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress.

Intense media scrutiny surrounded the actress in 1958 when her teenage daughter Cheryl Crane stabbed Turner's lover Johnny Stompanato to death in their home during a domestic struggle. Her next film, Imitation of Life (1959), proved to be one of the greatest commercial successes of her career, and her starring role in Madame X (1966) earned her a David di Donatello Award for Best Foreign Actress. Turner spent most of the 1970s and early 1980s in semi-retirement, making her final film appearance in 1980. In 1982, she accepted a much-publicized and lucrative recurring guest role in the television series Falcon Crest, which afforded the series notably high ratings. In 1992, Turner was diagnosed with throat cancer and died of the disease three years later at age 74.

Life and career[]

1921–1936: Early life and education[]

Lana Turner was born Julia Jean Turner[6][7][b] on February 8, 1921,[c] at Providence Hospital[13] in Wallace, Idaho, a small mining community in the Idaho Panhandle region.[14][15] She was the only child of John Virgil Turner, a miner from Montgomery, Alabama of Dutch descent, and Mildred Frances Cowan from Lamar, Arkansas, who had English, Scottish and Irish ancestry. Mildred was four days shy of her own 17th birthday when she gave birth to her only child.[16] Lana's parents had first met while 14-year-old Mildred, the daughter of a mine inspector, was visiting Picher, Oklahoma, with her father, who was inspecting local mines there.[8] John was 24 years old at the time, and Mildred's father objected to the courtship. Shortly after, the two eloped and moved west, settling in Idaho.[17]

The family lived in Burke, Idaho at the time of Turner's birth,[18] and relocated to nearby Wallace in 1925,[d] where her father opened a dry cleaning service and worked in the local silver mines.[20] As a child, Turner was known to family and friends as Judy.[21] She expressed interest in performance at a young age, performing short dance routines at her father's Elks chapter in Wallace.[22] At age three, she performed an impromptu dance routine at a charity fashion show in which her mother was modeling.[22]

The Turner family struggled financially, and relocated to San Francisco when she was six years old, after which her parents separated.[23] On December 14, 1930,[24] her father won some money at a traveling craps game, stuffed his winnings in his left sock, and headed for home. He was later found bludgeoned to death on the corner of Minnesota and Mariposa Streets, on the edge of San Francisco's Potrero Hill and the Dogpatch District, with his left shoe and sock missing.[21][25] His robbery and homicide were never solved,[21] and his death had a profound effect on Turner.[26] "I know that my father's sweetness and gaiety, his warmth and his tragedy, have never been far from me," she later said. "That, and a sense of loss and of growing up too fast."[27]

Turner sometimes lived with family friends or acquaintances so that her impoverished mother could save money.[28] They also frequently moved, for a time living in Sacramento and throughout the San Francisco Bay Area.[29] Following her father's death, Turner lived for a period in Modesto with a family who physically abused her and "treated her like a servant".[27] Her mother worked 80 hours per week as a beautician to support herself and her daughter,[30][31] and Turner recalled sometimes "living on crackers and milk for half a week".[29]

While baptized a Protestant at birth,[32] Turner attended Mass with the Hislops, a Catholic family with whom her mother had temporarily boarded her in Stockton, California.[9] She became "thrilled" by the ritual practices of the church,[9] and when she was seven, her mother allowed her to formally convert to Roman Catholicism.[9][33] Turner subsequently attended the Convent of the Immaculate Conception[10] in San Francisco, hoping to become a nun.[22] In the mid-1930s, Turner's mother developed respiratory problems and was advised by her doctor to move to a drier climate, upon which the two moved to Los Angeles in 1936.[22][25]

1937–1939: Discovery and early films[]

Her hair was dark, messy, uncombed. Her hands were trembling so she could barely read the script. But she had that sexy clean quality I wanted. There was something smoldering underneath that innocent face.

– Mervyn LeRoy on Turner during her first audition, December 1936[34]

Turner's discovery is considered a show-business legend and part of Hollywood mythology among film and popular cultural historians.[35][36][e] One version of the story erroneously has her discovery occurring at Schwab's Pharmacy,[39] which Turner claimed was the result of a reporting error that began circulating in articles published by columnist Sidney Skolsky.[38] By Turner's own account, she was a junior at Hollywood High School when she skipped a typing class and bought a Coca-Cola at the Top Hat Malt Shop[34][40] located on the southeast corner of Sunset Boulevard and McCadden Place.[41] While in the shop, she was spotted by William R. Wilkerson, publisher of The Hollywood Reporter.[35] Wilkerson was attracted by her beauty and physique, and asked her if she was interested in appearing in films, to which she responded: "I'll have to ask my mother first."[38] With her mother's permission, Turner was referred by Wilkerson to the actor/comedian/talent agent Zeppo Marx.[42] In December 1936, Marx introduced Turner to film director Mervyn LeRoy, who signed her to a $50 weekly contract with Warner Bros. on February 22, 1937 ($900 in 2020 dollars [43]).[34] She soon became a protégée of LeRoy, who suggested that she take the stage name Lana Turner, a name she would come to legally adopt several years later.[44]

Turner made her feature film debut in LeRoy's They Won't Forget (1937),[45] a crime drama in which she played a teenage murder victim. Though Turner only appeared on screen for a few minutes,[46] Wilkerson wrote in The Hollywood Reporter that her performance was "worthy of more than a passing note".[47] The film earned her the nickname of the "Sweater Girl" for her form-fitting attire, which accentuated her bust.[42][48] Turner always detested the nickname,[49] and upon seeing a sneak preview of the film, she recalled being profoundly embarrassed and "squirming lower and lower" into her seat.[33] She stated that she had "never seen myself walking before… [It was] the first time [I was] conscious of my body."[33] Several years after the film's release, Modern Screen journalist Nancy Squire wrote that Turner "made a sweater look like something Cleopatra was saving for the next visiting Caesar".[7] Shortly after completing They Won't Forget, she made an appearance in James Whale's historical comedy The Great Garrick (1937), a biographical film about British actor David Garrick, in which she had a small role portraying an actress posing as a chambermaid.[50][51]

In late 1937, LeRoy was hired as an executive at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), and asked Jack L. Warner to allow Turner to relocate with him to MGM.[52] Warner obliged, as he believed Turner would not "amount to anything".[53] Turner left Warner Bros. and signed a contract with MGM for $100 a week ($1,800 in 2020 dollars [43]).[54] The same year, she was loaned to United Artists for a minor role as a maid in The Adventures of Marco Polo.[47] Her first starring role for MGM was scheduled to be an adaptation of The Sea-Wolf, co-starring Clark Gable, but the project was eventually shelved.[55] Instead, she was assigned opposite teen idol Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland in the Andy Hardy film Love Finds Andy Hardy (1938).[56] During the shoot, Turner completed her studies with an educational social worker, allowing her to graduate high school that year.[57] The film was a box-office success,[58] and her appearance in it as a flirtatious high school student convinced studio head Louis B. Mayer that Turner could be the next Jean Harlow, a sex symbol who had died six months before Turner's arrival at MGM.[59]

Mayer helped further Turner's career by giving her roles in several youth-oriented films in the late 1930s, such as the comedy Rich Man, Poor Girl (1938) in which she played the sister of a poor woman romanced by a wealthy man, and Dramatic School (1938), in which she portrayed Mado, a troubled drama student.[60] In the former, she was billed as the "Kissing Bug from the Andy Hardy film".[60] Upon completing Dramatic School, Turner screen-tested for the role of Scarlett O'Hara in Gone with the Wind (1939).[60] She was then cast in a supporting part as a "sympathetic bad girl" in Calling Dr. Kildare (1939), MGM's second entry in the Dr. Kildare series.[60] This was followed by These Glamour Girls (1939), a comedy in which she portrayed a taxi dancer invited to attend a dance with a male coed at his elite college.[61] Turner's onscreen sex appeal in the film was reflected by a review in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in which she was characterized as "the answer to 'oomph'".[62] In her next film, Dancing Co-Ed (1939), Turner was given first billing portraying Patty Marlow, a professional dancer who enters a college as part of a rigged national talent contest.[63] The film was a commercial success, and led to Turner appearing on the cover of Look magazine.[64]

In February 1940, Turner garnered significant publicity when she eloped to Las Vegas with 28-year-old bandleader Artie Shaw, her co-star in Dancing Co-Ed.[65][66] Though they had only briefly known each other, Turner recalled being "stirred by his eloquence", and after their first date the two spontaneously decided to get married.[67] Their marriage only lasted four months, but was highly publicized, and led MGM executives to grow concerned over Turner's "impulsive behavior".[68] In the spring of 1940, after the two had divorced, Turner discovered she was pregnant and had an abortion.[69] In contemporaneous press, it was noted she had been hospitalized for "exhaustion".[69] She would later recall that Shaw treated her "like an untutored blonde savage, and took no pains to conceal his opinion".[64] In the midst of her marriage to Shaw, she starred in We Who Are Young, a drama in which she played a woman who marries her coworker against their employer's policy.[70]

1940–1945: War years and film stardom[]

In 1940, Turner appeared in her first musical film, Two Girls on Broadway, in which she received top billing over established co-stars Joan Blondell and George Murphy.[64] A remake of The Broadway Melody, the film was marketed as featuring Turner's "hottest, most daring role".[64] The following year, she had a lead role in her second musical, Ziegfeld Girl, opposite James Stewart, Judy Garland and Hedy Lamarr.[71] In the film, she portrayed Sheila Regan, an alcoholic aspiring actress based on Lillian Lorraine.[72][73] Ziegfeld Girl marked a personal and professional shift for Turner; she claimed it as the first role that got her "interested in acting",[74] and the studio, impressed by her performance, marketed the film as featuring her in "the best role of the biggest picture to be released by the industry's biggest company".[75] The film's high box-office returns elevated Turner's profitability, and MGM gave her a weekly salary raise to $1,500 as well as a personal makeup artist and trailer ($27,709 in 2020 dollars [43]).[76] After completing the film, Turner and co-star Garland remained lifelong friends, and lived in houses next to one another in the 1950s.[77]

Following the success of Ziegfeld Girl, Turner took a supporting role as an ingénue in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1941), a Freudian-influenced horror film, opposite Spencer Tracy and Ingrid Bergman.[78] MGM had initially cast Turner in the lead, but Tracy specifically requested Bergman for the part.[79] The studio recast Turner in the smaller role, though she was still given top billing.[79] While the film was financially successful,[80] Time magazine panned it, calling it "a pretentious resurrection of Robert Louis Stevenson's ghoulish classic ... As for Lana Turner, fully clad for a change, and the rest of the cast ... they are as wooden as their roles."[81]

Turner was then cast in the Western Honky Tonk (1941), the first of four films in which she would star opposite Clark Gable.[82] The Turner-Gable films' successes were often heightened by gossip-column rumors about a relationship between the two.[83] In January 1942, she began shooting her second picture with Gable, titled Somewhere I'll Find You;[84] however, the production was halted for several weeks after the death of Gable's wife, Carole Lombard, in a plane crash.[85] Meanwhile, the press continued to fuel rumors that Turner and Gable were romantic offscreen, which Turner vehemently denied.[86] "I adored Mr. Gable, but we were [just] friends," she later recalled. "When six o'clock came, he went his way and I went mine."[33] Her next project was Johnny Eager (1941), a violent mobster film in which she portrayed a socialite.[87][88] James Agee of Time magazine was critical of co-star Robert Taylor's performance and noted: "Turner is similarly handicapped: Metro has swathed her best assets in a toga, swears that she shall become an actress, or else. Under these adverse circumstances, stars Taylor and Turner are working under wraps."[89]

At the advent of World War II, Turner's increasing prominence in Hollywood led to her becoming a popular pin-up girl,[90] and her image appeared painted on the noses of U.S. fighter planes, bearing the nickname "Tempest Turner".[91] In June 1942, she embarked on a 10-week war-bond tour throughout the western United States with Gable.[92] During the tour, she began promising kisses to the highest war bond buyers; while selling bonds at the Pioneer Courthouse in Portland, Oregon, she sold a $5,000 bond to a man for two kisses,[93] and another to an elderly man for $50,000.[92] Arriving to sell bonds in her hometown of Wallace, Idaho, she was greeted with a banner that read "Welcome home, Lana", followed by a large celebration during which the mayor declared a holiday in her honor.[94] Upon completing the tour, Turner had sold $5.25 million in war bonds.[92] Throughout the war, Turner continued to make regular appearances at U.S. troop events and area bases, though she confided to friends that she found visiting the hospital wards of injured soldiers emotionally difficult.[95]

In July 1942,[96] Turner met her second husband, actor-turned-restaurateur Joseph Stephen "Steve" Crane, at a dinner party in Los Angeles.[97] The two eloped to Las Vegas a week after they began dating.[98][99] Their marriage was annulled by Turner four months later upon discovering that Crane's previous divorce had not yet been finalized.[99] After discovering she was pregnant in November 1942, Turner remarried Crane in Tijuana in March 1943.[96] During her early pregnancy, she filmed the comedy Marriage Is a Private Affair, in which she starred as a carefree woman struggling to balance her new life as a mother.[100] Though she wanted multiple children, Turner had Rh-negative blood, which caused fetal anemia and made it difficult to carry a child to term.[101][102] Turner was urged by doctors to undergo a therapeutic abortion to avoid potentially life-threatening complications, but she managed to carry the child to term.[103] She gave birth to a daughter, Cheryl, on July 25, 1943.[100] Turner's blood condition resulted in Cheryl being born with near-fatal erythroblastosis fetalis.[104][105]

Meanwhile, publicity over Turner's remarriage to Crane led MGM to play up her image as a sex symbol in Slightly Dangerous (1943), with Robert Young, Walter Brennan and Dame May Whitty, in which she portrayed a woman who moves to New York City and poses as the long-lost daughter of a millionaire.[106] Released in the midst of Turner's pregnancy, the film was financially successful[107] but received mixed reviews, with Bosley Crowther of The New York Times writing: "No less than four Metro writers must have racked their brains for all of five minutes to think up the rags-to-riches fable ... Indeed, there is cause for suspicion that they didn't even bother to think."[108] Critic Anita Loos praised Turner's performance in the film, writing: "Lana Turner typifies modern allure. She is the vamp of today as Theda Bara was of yesterday. However, she doesn't look like a vamp. She is far more deadly because she lets her audience relax."[109]

In August 1944, Turner divorced Crane, citing his gambling and unemployment as primary reasons.[110] A lifelong Democrat, she spent the remainder of the year campaigning for Franklin D. Roosevelt during the 1944 presidential election.[111] In 1945, she co-starred with Laraine Day and Susan Peters in Keep Your Powder Dry, a war drama about three disparate women who join the Women's Army Corps.[112] She was then cast as the female lead in Week-End at the Waldorf, a loose remake of Grand Hotel (1932) in which she portrayed a stenographer (a role originated by Joan Crawford).[113] The film was a box-office hit.[113][114]

1946–1948: Expansion to dramatic roles[]

After the war, Turner was cast in a lead role opposite John Garfield in The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), a film noir based on James M. Cain's debut novel of the same name.[115] She portrayed Cora, an ambitious woman married to a stodgy, older owner of a roadside diner, who falls in love with a drifter and their desire to be together motivates them to murder her husband.[116] The classic film noir marked a turning point in Turner's career as her first femme fatale role.[117] Reviews of the film, including Turner's performance, were glowing, with Bosley Crowther of The New York Times writing it was "the role of her career".[118] Life magazine named the film its "Movie of the Week" in April 1946, and noted that both Turner and Garfield were "aptly cast" and "take over the screen, [creating] more fireworks than the Fourth of July".[119] Turner commented on her decision to take the role:

I finally got tired of making movies where all I did was walk across the screen and look pretty. I got a big chance to do some real acting in The Postman Always Rings Twice, and I'm not going to slip back if I can help it. I tried to persuade the studio to give me something different. But every time I went into my argument about how bad a picture was, they'd say, "well, it's making a fortune". That licked me.[120]

The Postman Always Rings Twice became a major box office success, which prompted the studio to take more risks on Turner, casting her outside of the glamorous sex-symbol roles for which she had come to be known.[120] In August 1946, it was announced she would replace Katharine Hepburn in the big-budget historical drama Green Dolphin Street (1947), a role for which she darkened her hair and lost 15 pounds.[120][121] The film was produced by Carey Wilson, who insisted on casting Turner based on her performance in The Postman Always Rings Twice. In the film, she portrayed the daughter of a wealthy patriarch who pursues a relationship with a man in love with her sister.[121] Turner later recalled she was surprised about replacing Hepburn, saying: "I'm about the most un-Hepburnish actress on the lot. But it was just what I wanted to do."[120] It was her first starring role that did not center on her looks. In an interview, Turner said: "I even go running around in the jungles of New Zealand in a dress that's filthy and ragged. I don't wear any make-up and my hair's a mess." Nevertheless, she insisted she would not give up her glamorous image.[120] In the midst of filming Green Dolphin Street, Turner began an affair with actor Tyrone Power,[122][123] whom she considered to be the love of her life.[124] She discovered she was pregnant with Power's child in the fall of 1947, but chose to have an abortion.[124][33] During this time, she also had romantic affairs with Frank Sinatra[125] and Howard Hughes, the latter of which lasted for 12 weeks in late 1946.[126]

Turner's next film was the romantic drama Cass Timberlane, in which she played a young woman in love with an older judge, a role for which Jennifer Jones, Vivien Leigh and Virginia Grey had also been considered.[127] As of early 1946, Turner was set for the role, but schedules with Green Dolphin Street almost prohibited her from taking it, and by late 1946, she was nearly recast.[128] Production of Cass Timberlane was exhausting for Turner, because it was shot in between retakes of Green Dolphin Street.[129] Cass Timberlane earned Turner favorable reviews, with Variety noting: "Turner is the surprise of the picture via her top performance thespically. In a role that allows her the gamut from tomboy to the pangs of childbirth and from being another man's woman to remorseful wife, she seldom fails to acquit herself creditably."[130]

In August 1947, immediately upon completion of Cass Timberlane, Turner agreed to appear as the female lead in the World War II-set romantic drama Homecoming (1948), in which she was again paired with Clark Gable, portraying a female army lieutenant who falls in love with an American surgeon (Gable).[131] She was the studio's first choice for the role, but it was reluctant to offer her the part, considering her overbooked schedule.[131] Homecoming was well received by audiences, and Turner and Gable were nicknamed "the team that generates steam".[132] By this period, Turner was at the zenith of her film career, and was not only MGM's most popular star, but also one of the ten highest-paid women in the United States, with annual earnings of $226,000.[113][133]

1948–1952: Studio rebranding and personal struggles[]

In late 1947, Turner was cast as Lady de Winter in The Three Musketeers, her first Technicolor film.[134][135] Around this time, she began dating Henry J. "Bob" Topping Jr., a millionaire socialite and brother of New York Yankees owner Dan Topping, and a grandson of tin-plate magnate Daniel G. Reid.[96] Topping proposed to her at the 21 Club in New York City by dropping a diamond ring into her martini, and they married shortly after in April 1948 at the Topping family mansion in Greenwich, Connecticut.[136][137] Turner's wedding celebrations interfered with her filming schedule for The Three Musketeers, and she arrived to the set three days late.[138][139] Studio head Louis B. Mayer threatened to suspend her contract, but Turner managed to leverage her box-office draw with MGM to negotiate an expansion of her role in the film, as well as a salary increase amounting to $5,000 per week ($57,951 in 2020 dollars [43]).[140][141] The Three Musketeers went on to become a box-office success, earning $4.5 million ($52,155,738 in 2020 dollars [43]),[142] but Turner's contract was put on temporary suspension by Mayer after production finished.[143] After the release of The Three Musketeers, Turner discovered she was pregnant; in early 1949, she went into premature labor and gave birth to a stillborn baby boy in New York City.[144]

In 1949, Turner was to star in A Life of Her Own (1950), a George Cukor-directed drama about a woman who aspires to be a model in New York City. The project was shelved for several months, and Turner told journalists in December 1949: "Everybody agrees that the script is still a pile of junk. I'm anxious to get started. By the time this one comes out, it will be almost three years since I was last on the screen, in The Three Musketeers. I don't think it's healthy to stay off the screen that long."[145] Though she was unenthusiastic about the screenplay, Turner agreed to appear in the film after executives promised her suspension would be lifted upon doing so.[143] A Life of Her Own was among the least successful of Cukor's films, receiving unfavorable reviews and low box-office sales.[146] On May 24, 1950, Turner left her handprints and footprints in cement in front of Grauman's Chinese Theatre.[147]

In response to the poor reception for A Life of Her Own, MGM attempted to rebrand Turner by casting her in musicals.[148] The first, Mr. Imperium, released in March 1951, was a box-office flop, and had Turner starring as an American woman who is wooed by a European prince.[149] "The script was stupid," she recalled. "I fought against doing the picture, but I lost."[150] It earned her unfavorable reviews, with one critic from the St. Petersburg Times writing: "Without Lana Turner, Mr. Imperium ... would be a better picture."[151]

During this period, Turner's personal finances were in disarray, and she was facing bankruptcy.[152] Suffering from chronic depression over her career and financial problems, she attempted suicide in September 1951 by slitting her wrists in a locked bathroom.[153] She was saved by her business manager, Benton Cole, who broke down the bathroom door and called emergency medical services.[153] The following year, she began filming her second musical, The Merry Widow. During the shoot, Turner began an affair with her co-star Fernando Lamas, which ended after Lamas physically assaulted her; the incident also caused Lamas to lose his MGM contract upon the production's completion.[154] The Merry Widow proved more commercially successful than Turner's previous musical, Mr. Imperium, despite receiving unfavorable critical reviews.[155]

Turner's next project was opposite Kirk Douglas in Vincente Minnelli's The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), a drama focusing on the rise and fall of a Hollywood film mogul, in which Turner portrayed an alcoholic movie star.[156] The Bad and the Beautiful was both a critical and commercial success, and earned her favorable reviews.[157] A little over a week before the film's release in December 1952, Turner divorced her third husband, Bob Topping.[96] She later claimed Topping's drinking problem and excessive gambling as her impetus for the divorce.[158] Her next film project was Latin Lovers (1953), a romantic musical in which Lamas had originally been cast. He was replaced by Ricardo Montalbán.[159]

1953–1957: MGM departure and film resurgence[]

In the spring of 1953, Turner relocated to Europe for 18 months to make two films under a tax credit for American productions shot abroad.[160] The films were Flame and the Flesh, in which she portrayed a manipulative woman who takes advantage of a musician, and Betrayed, an espionage thriller set in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands; the latter marked Turner's fourth and final film appearance opposite Clark Gable.[161] In The New York Times, Bosley Crowther wrote of Betrayed: "By the time this picture gets around to figuring out whether the betrayer is Miss Turner or Mr. Mature, it has taken the audience through such a lengthy and tedious amount of detail that it has not only frayed all possible tension but it has aggravated patience as well."[162] Upon returning to the United States in September 1953, Turner married actor Lex Barker,[96] whom she had been dating since their first meeting at a party held by Marion Davies in the summer of 1952.[163]

In 1955, MGM's new studio head Dore Schary had Turner star as a pagan temptress in the Biblical epic The Prodigal (1955), her first CinemaScope feature.[164][165] She was reluctant to appear in the film because of the character's scanty, "atrocious" costumes and "stupid" lines, and during the shoot struggled to get along with co-star Edmund Purdom, whom she later described as "a young man with a remarkably high opinion of himself".[166] Variety deemed the film "a big-scale spectacle ...End result of all this flamboyant polish, however, is only fair entertainment."[167] Turner was next cast in John Farrow's The Sea Chase (1955), an adventure film starring John Wayne, in which she portrayed a femme fatale spy aboard a ship.[168] The film, released one month after The Prodigal, was a commercial success.[169]

MGM then gave Turner the titular role of Diane de Poitiers in the period drama Diane (1956), which had originally been optioned by the studio in the 1930s for Greta Garbo.[170] After completing Diane, Turner was loaned to 20th Century-Fox to headline The Rains of Ranchipur (1955), a remake of The Rains Came (1939), playing the wife of an aristocrat in the British Raj opposite Richard Burton.[171][172] The production was rushed to accommodate a Christmas release and was completed in only three months, but it received unfavorable reviews from critics.[173] Meanwhile, Diane was given a test screening in late December 1955, and was met with poor response from audiences.[173] Though an elaborate marketing campaign was crafted to promote the film, it was a box-office flop,[174] and MGM announced in February 1956 that it was opting not to renew Turner's contract.[175] Turner gleefully told a reporter at the time that she was "walking around in a daze. I've been sprung. After 18 years at MGM, I'm a free agent ...I used to go on a bended knee to the front office and say, please give me a decent story. I'll work for nothing, just give me a good story. So what happened? The last time I begged for a good story they gave me The Prodigal."[176] At the time of her contract termination, Turner's films had earned the studio more than $50 million.[176]

In 1956, Turner discovered she was pregnant with Barker's child, but gave birth to a stillborn baby girl seven months into the pregnancy.[177] In July 1957,[96] she filed for divorce from Barker after her daughter Cheryl alleged that he had regularly molested and raped her over the course of their marriage.[178][179] According to Cheryl, Turner confronted Barker before forcing him out of their home at gunpoint.[180] Weeks after her divorce, Turner began filming 20th Century-Fox's Peyton Place, in which she had been cast in the lead role of Constance MacKenzie, a New England mother struggling to maintain a relationship with her teenage daughter.[181] The film, directed by Mark Robson, was adapted from Grace Metalious' best-selling novel of the same name.[182] Released in December 1957, Peyton Place was a major blockbuster success, which worked in Turner's favor as she had agreed to take a percentage of the film's overall earnings instead of a salary.[183] She also received critical acclaim, with Variety noting that "Turner looks elegant" and "registers strongly",[184] and, for the first and only time, she was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actress.[185] Though grateful for the nomination, Turner would later state that she felt it was not "one of my better roles".[186]

1958–1959: Johnny Stompanato homicide scandal[]

In January 1958, Paramount Pictures released The Lady Takes a Flyer, a romantic comedy in which Turner portrayed a female pilot.[187] While shooting the film the previous spring, she had begun receiving phone calls and flowers on the set from mobster Johnny Stompanato, using the name "John Steele".[188] Stompanato had close ties to the Los Angeles underworld and gangster Mickey Cohen, which he feared would dissuade her from dating him.[189] He pursued Turner aggressively, sending her various gifts.[190] Turner was "thoroughly intrigued" and began casually dating him.[191] After a friend informed her of who Stompanato actually was, she confronted him and tried to break off the affair.[192] Stompanato was not easily deterred, and over the course of the following year, they carried on a relationship filled with violent arguments, physical abuse and repeated reconciliations.[193][194] Turner would also claim that on one occasion he drugged her and took nude photographs of her while unconscious, potentially to use as blackmail.[195]

In September 1957, Stompanato visited Turner in London, where she was filming Another Time, Another Place, co-starring Sean Connery.[196] Their meeting was initially happy, but they soon began fighting. Stompanato became suspicious when Turner would not allow him to visit the set and, during one fight, he violently choked her.[197] To avoid further confrontation, Turner and her makeup artist, Del Armstrong, called Scotland Yard in order to have Stompanato deported.[198][199] Stompanato got wind of the plan and showed up on the set with a gun, threatening her and Connery.[200] Connery answered by grabbing the gun out of Stompanato's hand and twisting his wrist, causing him to run off the set.[201] Turner and Armstrong later returned with two Scotland Yard detectives to the rented house where she and Stompanato were staying. The detectives advised Stompanato to leave and escorted him out of the house and to the airport, where he boarded a plane back to the U.S.[202]

On the evening of March 26, 1958, Turner attended the Academy Awards to observe her nomination for Peyton Place and present the award for Best Supporting Actor.[203] Stompanato, angered that he did not attend with her, awaited her return home that evening, whereupon he physically assaulted her.[204] Around 8:00 p.m. on Friday, April 4, Stompanato arrived at Turner's rented home at 730 North Bedford Drive in Beverly Hills.[205][206] The two began arguing heatedly in the bedroom, during which Stompanato threatened to kill Turner, her daughter Cheryl and her mother.[193] Fearing that her mother's life was in danger, Cheryl - who had been watching television in an adjacent room - grabbed a kitchen knife and ran to Turner's defense.[207]

According to testimony provided by Turner, Stompanato died at the scene when Cheryl, who had been listening to the couple's fight behind the closed door, stabbed Stompanato in the stomach when Turner attempted to usher him out of the bedroom.[208] Turner testified that she initially believed Cheryl had punched him, but realized Stompanato had been stabbed when he collapsed and she saw blood on his shirt.[208]

Because of Turner's fame and the fact that the killing involved her teenage daughter, the case quickly became a media sensation.[209] More than 100 reporters and journalists attended the April 12, 1958 inquest, described by attendees as "near-riotous".[210] After four hours of testimony and approximately 25 minutes of deliberation, the jury deemed the killing a justifiable homicide.[211][212] Cheryl remained a temporary ward of the court until April 24, when a juvenile court hearing was held, during which the judge expressed concerns over her receiving "proper parental supervision".[212] She was ultimately released to the care of her grandmother, and was ordered to regularly visit a psychiatrist alongside her parents.[212]

Though Turner and her daughter were exonerated of any wrongdoing, public opinion on the event was varied, with numerous publications intimating that Turner's testimony at the inquest was a performance; Life magazine published a photo of Turner testifying in court along with stills of her in courtroom scenes from three of her films.[213] The scandal also coincided with the release of Another Time, Another Place, and the film was met with poor box-office receipts and a lackluster critical response.[214] Stompanato's family sought a wrongful death suit of $750,000 in damages against both Turner and her ex-husband, Steve Crane. In the suit, Stompanato's son alleged that Turner had been responsible for his death, and that her daughter had taken the blame.[215] The suit was settled out of court for a reported $20,000 in May 1962.[216] A 1962 novel by Harold Robbins entitled Where Love Has Gone and its subsequent film adaptation were inspired by the event.[217]

1959–1965: Financial successes[]

In the wake of negative publicity related to Stompanato's death, Turner accepted the lead role in Ross Hunter's remake of Imitation of Life (1959) under the direction of Douglas Sirk.[218] She portrayed a struggling stage actress who makes personal sacrifices to further her career.[219] The production was difficult for Turner given the recent events of her personal life, and she suffered a panic attack on the first day of filming.[220] Her co-star Juanita Moore recalled that Turner cried for three days after filming a scene in which Moore's character dies.[221] When she returned to the set, "her face was so swollen, she couldn't work", Moore said.[222]

Released in the spring of 1959, Imitation of Life was among the year's biggest successes, and the biggest of Turner's career; by opting to receive 50% of the film's earnings rather than receiving a salary, she earned more than two million dollars.[223] Imitation of Life made more than $50 million in box office receipts.[224] Reviews were mixed,[225] although Variety praised her performance, writing: "Turner plays a character of changing moods, and her changes are remarkably effective, as she blends love and understanding, sincerity and ambition. The growth of maturity is reflected neatly in her distinguished portrayal."[226] Critics and audiences could not help noticing that the plots of Peyton Place and Imitation of Life both seemed to mirror certain parts of Turner's private life, resulting in comparisons she found painful.[227] Both films depicted the troubled, complicated relationship between a single mother and her teenage daughter.[228] During this time, Turner's daughter Cheryl privately came out as a lesbian to her parents, who were both supportive of her.[211] Despite this, Cheryl ran away from home multiple times and the press wrote about her rebelliousness.[223][229] Worried she was still suffering from the trauma of Stompanato's death, Turner sent Cheryl to the Institute of Living in Hartford, Connecticut.[230]

Shortly before the release of Imitation of Life in the spring of 1959, Turner was cast in a lead role in Otto Preminger's Anatomy of a Murder, but walked off the set over a wardrobe disagreement, effectively dropping out of the production.[231][232] She was replaced by Lee Remick.[233] Instead, Turner took a lead role as a disturbed socialite in the film noir Portrait in Black (1960) opposite Anthony Quinn and Sandra Dee, which was a box-office success despite bad reviews.[234][235] Ray Duncan of the Independent Star-News wrote that Turner "suffers prettily through it all, like a fashion model with a tight-fitting shoe".[236]

In November 1960, Turner married her fifth husband, Frederick "Fred" May, a rancher and member of the May department-store family whom she had met at a beach party in Malibu shortly after filming Imitation of Life.[237] Turner moved in with him on his ranch in Chino, California, where the two took care of horses and other animals.[238][216] The following year, she made her final film at MGM with Bob Hope in Bachelor in Paradise (1961), a romantic comedy about an investigative writer (Hope) working on a book about the wives of a lavish California community; the film received a mostly positive critical reception.[239] Upon completing filming, Turner collected the remaining $92,000 from her pension fund with MGM.[240] The same year, she starred in By Love Possessed (1961), based on a bestselling novel by James Gould Cozzens.[241] The film became the first in-flight movie to be shown on a regular basis on a scheduled airline flight when TWA showed it to its first-class passengers.[242]

In mid-1962, Turner filmed Who's Got the Action?, a comedy in which she portrayed the wife of a gambling addict opposite Dean Martin.[243] In September of that year,[244] Turner and May separated, divorcing shortly after in October.[96] They remained friends throughout her later life.[33] In 1965, she met Hollywood producer and businessman Robert Eaton, who was ten years her junior, through business associates.[245] The two married in June of that year at his family's home in Arlington, Virginia.[246]

1966–1985: Later films, television and theatre[]

In 1966, Turner had her last major starring role in the courtroom drama film Madame X, based on the 1904 play by Alexandre Bisson, in which Turner portrayed a lower-class woman who marries into a wealthy family.[247] A review in the Chicago Tribune praised her performance, noting: "when she takes the stand in the final (with Keir Dullea) courtroom scene, her face resembling a dust bowl victory garden, it's the most devastating denouement since Barbara Fritchie poked her head out the window."[248] Kaspar Monahan of the Pittsburgh Press lauded her performance, writing: "Her performance, I think, is far and away her very best, even rating Oscar consideration in next year's Academy Award race, unless the culture snobs gang up against her."[249] The role earned Turner a David di Donatello Golden Plaque Award for Best Foreign Actress that year.[250] In late 1968, she began filming the low-budget thriller The Big Cube, in which she portrayed a glamorous heiress being dosed with LSD by her stepdaughter in hopes of driving her insane and receiving the family estate.[251] One critic deemed Turner's acting in the film "strained and amateurish", and declared it "one of her poorest performances".[252] In April 1969,[253] Turner filed for divorce from Eaton after four years of marriage upon discovering he had been unfaithful to her.[254] Weeks later, on May 9, 1969, she married Ronald Pellar, a nightclub hypnotist whom she had met at a Los Angeles disco.[255] According to Turner, Pellar (also known as Ronald Dante or Dr. Dante)[256] falsely claimed to have been raised in Singapore and to have a Ph.D. in psychology.[257]

With few film offers coming in, Turner signed on to appear in the television series Harold Robbins' The Survivors.[258] Premiering in September 1969, the series was given a major national marketing campaign, with billboards featuring life-sized images of Turner.[259] Despite ABC's extensive publicity campaign and the presence of other big-name stars, the program fared badly, and it was canceled halfway into the season after a 15-week run in 1970.[259] Meanwhile, after six months of marriage, Turner discovered Pellar had stolen $35,000 she had given him for an investment.[260] In addition, she later accused him of stealing $100,000 worth of jewelry from her.[260] Pellar denied the accusations and no charges were filed against him.[261] She filed for divorce in January 1970,[96] after which she claimed to be celibate for the remainder of her life.[262][263] Turner married a total of eight times to seven different husbands,[211] and later famously said: "My goal was to have one husband and seven children, but it turned out to be the other way around."[101]

Turner returned to feature films with a lead role in the 1974 British horror film Persecution, in which she played a disturbed wealthy woman tormenting her son.[264] Variety noted of her performance: "Under the circumstances, Turner's performance as Carrie, the perverted dame of the English manor, has reasonable poise."[265] In April 1975, Turner spoke at a retrospective gala in New York City examining her career, which was attended by Andy Warhol, Sylvia Miles, Rex Reed and numerous fans.[266] Her next film was Bittersweet Love (1976), a romantic comedy in which she portrayed the mother of a woman who unwittingly marries her half-brother.[267] Lawrence Van Gelder of The New York Times wrote that the film served "as a reminder that Miss Turner was never one of our subtler actresses".[268]

In the early 1970s, Turner transitioned to theater, beginning with a production of Forty Carats, which toured various East Coast cities in 1971.[269] A review in The Philadelphia Inquirer noted: "Miss Turner always could wear clothes well, and her Forty Carats is a fashion show in the guise of a frothy, little comedy. It wasn't much of a play even when Julie Harris was doing it, and it all but disappears under the old-time Hollywood glamor of Miss Turner's star presence."[270] In 1975, Turner gave a single performance as Jessica Poole in The Pleasure of His Company opposite Louis Jourdan at the Arlington Park Theater in Chicago.[271] From 1976 to 1978, she starred in a touring production of Bell, Book and Candle, playing Gillian Holroyd.[272][273] Critic Elaine Matas noted of a 1977 performance that Turner was "brilliant" and "the bright spot in an otherwise mediocre play".[274] In the fall of 1978, she appeared in a Chicago production of Divorce Me, Darling, an original play in which she portrayed a San Francisco divorce attorney.[275] During rehearsals, a stagehand told reporters that Turner was "the hardest working broad I've known".[276] Richard Christiansen of the Chicago Tribune praised her performance, writing that, "though she is still a very nervous and inexpert actress, she is giving by far her most winning performance".[275]

Between 1979 and 1980, Turner returned to theater, appearing in Murder Among Friends, a murder-mystery play that showed in various U.S. cities.[277][278][279] During this time, Turner was in the midst of a self-described "downhill slide".[280] She was suffering from an alcohol addiction that had begun in the late 1950s,[269] was missing performances and weighed only 95 pounds (43 kg).[280] In 1980, Turner made her final feature-film appearance alongside Teri Garr in the comedy horror film Witches' Brew. The same year, she had what she referred to as a "religious awakening", and again began practicing her Catholic faith.[281][282] On October 25, 1981, the National Film Society presented Turner with an Artistry in Cinema award.[283] In December 1981, it was announced that Turner would appear as the mysterious Jacqueline Perrault in an episode of Falcon Crest,[284] marking her first television role in 12 years.[285] Her appearance was a ratings success, and her character returned for an additional five episodes.[286]

In January 1982, Turner reprised her role in Murder Among Friends, which toured throughout the U.S. that year; paired with Bob Fosse's Dancin', the play earned a combined gross of $400,000 during one week at Pittsburgh's Heinz Hall in June 1982.[287] In September, Turner released an autobiography entitled Lana: The Lady, the Legend, the Truth.[288] She subsequently guest-starred on an episode of The Love Boat in 1985,[289] which marked her final on-screen appearance.

1986–1995: Illness and death[]

Turner was a regular drinker[269] and cigarette smoker for most of her life.[290][291] During her contract with MGM, photographs that showed her holding cigarettes had to be airbrushed at the studio's request in an effort to conceal her smoking.[290] In her early 60s, Turner stopped drinking to preserve her health,[282] but she was unable to quit smoking.[257] She was diagnosed with throat cancer in the spring of 1992.[292][293] In a press release, she stated that the cancer had been detected early and had not damaged her vocal cords or larynx.[293] She underwent exploratory surgery to remove the cancer,[293] but it had metastasized to her jaw and lungs.[294] After undergoing radiation therapy,[291] Turner announced that she was in full remission in early 1993.[295] The cancer was found to have returned in July 1994.[296]

In September 1994, Turner made her final public appearance at the San Sebastián International Film Festival in Spain to accept a Lifetime Achievement Award,[297] and was confined to a wheelchair for much of the event.[291] She died nine months later at the age of 74 on June 29, 1995, of complications from the cancer, at her home in Century City, Los Angeles, with her daughter by her side.[211][298] According to Cheryl, Turner's death was a "total shock", as she had appeared to be in better health and had recently completed seven weeks of radiation therapy.[263] Turner's remains were cremated and scattered in Oahu, Hawaii.[299][300]

Cheryl and her life partner Joyce LeRoy, whom Turner said she accepted "as a second daughter",[301] inherited some of Turner's personal effects and $50,000 in Turner's will. Her estate was estimated in court documents to be worth $1.7 million. Turner left the majority of her estate to her maid, Carmen Lopez Cruz, who had been her companion for 45 years and caregiver during her final illness.[302] Cheryl challenged the will, and Cruz said that the majority of the estate was consumed by probate costs, legal fees and medical expenses.[303]

Public and screen persona[]

Despite the reams of copy that have been written about me, even the supposedly private Lana, the press has never had any sense of who I am; they've even missed my humor, my love of gaiety and color ... Humor has been the balm of my life, but it's been reserved for those closest to me.

– Turner on her representation in press[304]

When Turner was discovered, MGM executive Mervyn LeRoy envisioned her as a replacement for the recently deceased Jean Harlow and began developing her image as a sex symbol.[305] In They Won't Forget (1937) and Love Finds Andy Hardy (1938), she embodied an "innocent sexuality" portraying ingénues.[306] Film historian Jeanine Basinger notes that she "represented the girl who'd rather sit on the diving board to show off her figure than get wet in the water ... the girl who'd rather kiss than kibbitz".[52] In her early films, Turner did not color her auburn hair—see Dancing Co-Ed (1939), in which she was billed "the red-headed sensation who brought "it" back to the screen".[307] 1941's Ziegfeld Girl was the first film to showcase Turner with platinum blonde hair, which she wore for much of the remainder of her life and for which she came to be known.[308]

After Turner's first marriage in 1940, columnist Louella Parsons wrote: "If Lana Turner will behave herself and not go completely berserk she is headed for a top spot in motion pictures. She is the most glamorous actress since Jean Harlow."[309] She also likened her to Clara Bow, adding: "Both of them, trusting and lovable, use their hearts instead of their heads. Lana ... has always acted hastily and been guided more by her own ideas than by any advance any studio gave her."[69] By the mid-1940s, Turner had been married and divorced three times, had given birth to her daughter Cheryl and had numerous publicized affairs.[223][306] However, her image in 1946's The Postman Always Rings Twice marked a departure from her strictly-sex symbol screen persona to that of a full-fledged femme fatale.[306]

By the 1950s, both critics and audiences began noting parallels between Turner's rocky personal life and the roles she played.[310] The likeness was most evident in Peyton Place and Imitation of Life, both films in which Turner portrayed single mothers struggling to maintain relationships with their teenage daughters.[311] Film scholar Richard Dyer cites Turner as an example of one of Hollywood's earliest stars whose publicized private life perceptibly inflected their careers: "Her career is marked by an unusually, even spectacularly, high degree of interpenetration between her publicly available private life and her films ... not only do her vehicles furnish characters and situations in accord with her off-screen image, but frequently incidents in them echo incidents in her life so that by the end of her career films like Peyton Place, Imitation of Life, Madame X and Love Has Many Faces seem in parts like mere illustrations of her life."[312]

Basinger echoes similar sentiments, noting that Turner was often "cast only in roles that were symbolic of what the public knew—or thought they knew—of her life from headlines she made as a person, not as a movie character ... Her person became her persona."[313] In addition, Basinger credits Turner as the first mainstream female star to "take the male prerogative openly for herself", publicly indulging in romances and affairs that in turn fueled the publicity surrounding her.[314] Film scholar Jessica Hope Jordan considers Turner an "implosion" of both a "real-life image and star image" and suggests that she utilized one to mask the other, thus rendering her representative of the "ultimate femme fatale".[315] Columnist Dorothy Kilgallen took note of the intersections between Turner's life and screen persona early in her career, writing in 1946:

Lana Turner is a super-star for many reasons but chiefly because she is the same off-screen as she is on. Some of the stars are magnetic dazzlers on celluloid and ordinary, practical, polo-coated little things in private life. Not so Lana. No one who adored her in movies would be disappointed to meet her in the flesh. The flesh is the same. The biography is as colorful as any plot she has ever romped through on screen. The clothes she wears are just like the clothes you pay to see her in on Saturday night at the Bijou. The physical allure is just as heavy when she looks at a headwaiter as when she looks at a hero.[316]

Historians have cited Turner as one of the most glamorous film stars of all time, an association that was made both during her lifetime[317][318][319] and after her death.[185] Commenting on her image, she once told a journalist: "Forsaking glamour is like forsaking my identity. It's an image I've worked too hard to obtain and preserve."[4] Michael Gordon, who directed Turner in Portrait in Black, remembered her as "a very talented actress whose chief reliability was what I regarded as impoverished taste ... Lana was not a dummy, and she would give me wonderful rationalizations why she should wear pendant earrings. They had nothing to do with the role, but they had to do with her particular self-image."[320]

According to her daughter, Turner's obsessive attention to detail often resulted in dressmakers storming out during dress fittings.[321] No matter the setting, Turner also took care to ensure she was always "camera-ready", wearing jewelry and makeup even while lounging in sweatpants.[322] Turner often purchased her favorite styles of shoes in every available color, at one time accumulating 698 pairs.[323] She favored the designers Salvatore Ferragamo, Jean Louis, Helen Rose and Nolan Miller.[321][324] Film historians Joe Morella and Edward Epstein have observed that, unlike many female stars, Turner "wasn't resented by female fans", and that women made up a large part of her fan base in later years.[325] Turner maintained her glamorous image into her late career; a 1966 film review characterized her as "the glitter and glamour of Hollywood".[4] While she consistently embraced her glamorous persona, she was also vocal about her dedication to acting[120] and attained a reputation as a versatile, hard-working performer.[11] She was an admirer of Bette Davis, whom she cited as her favorite actress.[217]

Legacy[]

Turner has been noted by historians as a sex symbol, a popular culture icon[4][313] and "a symbol of the American Dream fulfilled ... Because of her, being discovered at a soda fountain has become almost as cherished an ideal as being born in a log cabin."[4] Critic Leonard Maltin noted in 2005 that Turner "came to crystallize the opulent heights to which show business could usher a small-town girl, as well as its darkest, most tragic and narcissistic depths".[326] She has also been cited by scholars as a gay icon because of her glamorous persona and triumphs over personal struggles.[327] While discussions surrounding Turner have largely been based on her cultural prevalence, little scholarly study has been undertaken on her career,[328] and opinion of her legacy as an actress has divided critics. Upon Turner's death, John Updike wrote in The New Yorker that she "was a faded period piece, an old-fashioned glamour queen whose fifty-four films, over four decades didn't amount, retrospectively to much ... As a performer, she was purely a studio-made product."[329]

Defenders of Turner's acting ability, such as Jessica Hope Jordan[330] and James Robert Parish,[331] cite her performance in The Postman Always Rings Twice as an argument for the value of her work. Turner's role in the film has also caused her to be frequently associated with film noir and the femme fatale archetype in critical circles.[332][333][334] In a 1973 Films in Review retrospective on her career, Turner was referred to as "a master of the motion picture technique and a hardworking craftsman".[335] Jeanine Basinger has similarly championed Turner's acting, writing of her performance in The Bad and the Beautiful: "None of the sex symbols who have been touted as actresses—not Hayworth or Gardner or Taylor or Monroe—have ever given such a fine performance."[336]

Because of the intersections between Turner's high-profile, glamorous persona, and storied, often troubled personal life, she is included in critical discussions about the Hollywood studio system, specifically its capitalization on its stars' private travails.[328] Basinger considers her the "epitome of the Hollywood machine-made stardom".[337] Turner has also been cited in scholarly discussions of women's sexuality.[338]

Turner has been depicted and referenced in numerous works across literature, film, music and art. She was the subject of the poem "Lana Turner has collapsed" by Frank O'Hara,[339] and was depicted as a minor character in James Ellroy's novel L.A. Confidential (1990).[340] The Stompanato murder and its aftermath were also the basis of the Harold Robbins novel Where Love Has Gone (1962).[217] In popular music, Turner was referenced in songs recorded by Nina Simone[341] and Frank Sinatra,[342] and was the source of the stage name of singer-songwriter Lana Del Rey.[343][344] In 2002, artist Eloy Torrez included Turner in an outdoor mural, Portrait of Hollywood, painted on the auditorium of Hollywood High School, her alma mater.[345] Turner has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6241 Hollywood Boulevard.[11] In 2012, Complex named her the eighth-most infamous actress of all time.[346]

Filmography and credits[]

Notes[]

- ^ Turner pronounced her first name "Lah-nah",[1][2] and remarked her dislike for the alternate pronunciation "Lan-ah" (/lænə/). In a 1982 interview, Joan Rivers asked Turner how she preferred her name be spoken, and she joked: "Please, if you say "Lan-ah", I shall slaughter you."[3]

- ^ Some sources claim Turner's birth name to be Julia Jean Mildred Frances Turner. However, Turner notes in her autobiography that her birth certificate lists Julia Jean Turner as her official birth name.[8] She writes that she later adopted the middle names Mildred and Frances (saints' names as well as the given and middle names of her mother) after converting to Catholicism.[9]

- ^ Some sources (including the San Francisco Chronicle[10] and Los Angeles Times's Hollywood Walk of Fame series)[11] erroneously report her birth year as 1920. However, in her memoir, Turner cited her birth certificate as reading 1921,[8] and her daughter again confirmed this as her birth year in 2008.[12]

- ^ Per the official city of Wallace website, the Turner home in Wallace was located at 217 Bank Street, immediately west of downtown Wallace. The home is located within the Wallace Historic District, which is on the National Register of Historic Places (OMB no. 1024-0018).[19]

- ^ An article published in the Los Angeles Times in 1995 after Turner's death recounts the varied retellings of her discovery, and notes their status as show-business legends. A 2001 documentary on Turner refers to her discovery as the "most legendary star discovery story" in Hollywood.[37] Turner would dismiss the widely-circulated version that had the event occurring at Schwab's Pharmacy, insisting she met William R. Wilkerson at the Top Hat Malt Shop while drinking a Coca-Cola.[38]

References[]

- ^ Basinger 1976, p. 24.

- ^ Busch 1940, p. 65.

- ^ Turner, Lana (September 28, 1982). "Joan Rivers interviews Lana Turner". The Tonight Show (Interview). Interviewed by Joan Rivers. NBC.

- ^ a b c d e Fields 2007, p. 109.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 65.

- ^ "'Lana' Turner Official Now". Eugene Register-Guard. Eugene, Oregon: UP. May 7, 1950. p. 6D – via Google News.

- ^ a b Squire, Nancy Winslow (May 1943). "The Strange Case of Lana Turner". Modern Screen. p. 32. ISSN 0026-8429 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c Turner 1982, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d Turner 1982, p. 14.

- ^ a b San Francisco Chronicle Staff (July 3, 1995). "Editorial – Lana Turner: 1920–1995". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- ^ a b c Los Angeles Times Staff (June 30, 1995). "Lana Turner". Los Angeles Times. Hollywood Star Walk. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ Crane & De La Hoz 2008, p. 16.

- ^ Fernandes, Charles (July 3, 1995). "A star was born in Idaho; Wallace folks remember Turner's early years. Her family moved to San Francisco when she was 6 years old". Lewiston Tribune. Lewiston, Idaho. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ^ Grever, Brindley (May 15, 1941). "Lana Turner, Born in Wallace, Idaho, Twenty Years Ago, Now a Star". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Spokane, Washington. p. 16 – via Google News.

- ^ Turner 1982, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Turner 1982, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 10.

- ^ Buenneke, Troy D. (1991). "Burke, Idaho, 1884–1925: The Rise and Fall of a Mining Community". Idaho Yesterdays. Idaho Yesterdays : The Quarterly Journal of the Idaho Historical Society. 35–36. Idaho Historical Society. p. 26. ISSN 0019-1264.

- ^ Marsh, Greg. "Lana Turner lived in Historic Wallace". City of Wallace, Idaho. Archived from the original on December 13, 2007. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ^ Bamont & Jacobson 2017, p. 161.

- ^ a b c Basinger 1976, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d Los Angeles Times Staff (June 30, 1995). "Lana Turner, Glamorous Star of 50 Films, Dies at 75". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 11, 2016.

- ^ Wayne 2003, p. 164.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 15.

- ^ a b Wayne 2003, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 18.

- ^ a b Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 11.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 12.

- ^ a b Turner 1982, p. 13.

- ^ Fischer 1991, p. 22.

- ^ Basinger 1976, p. 21.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f Turner, Lana (September 29, 1982). "Guest: Lana Turner". The Phil Donahue Show (Interview). Interviewed by Phil Donahue. Multimedia Entertainment.

- ^ a b c Wayne 2003, p. 165.

- ^ a b Valentino 1976, p. 18.

- ^ Basinger 1976, p. 27.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 05:20.

- ^ a b c Wilkerson, W.R. III (July 1, 1995). "Writing the End to a True-to-Life Cinderella Story". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ Fields 2007, p. 79.

- ^ Lewis 2017, p. 91.

- ^ Lawson & Rufus 2000, p. 41.

- ^ a b Busch 1940, p. 64.

- ^ a b c d e 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 24.

- ^ Busch 1940, p. 63.

- ^ Langer 2001, at 6:05.

- ^ a b Wayne 2003, p. 166.

- ^ Fischer 1991, p. 187.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 6:40.

- ^ Jordan 2009, p. 221.

- ^ Valentino 1976, p. 63.

- ^ a b Basinger 1976, p. 31.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 29.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 7:00.

- ^ Breuer 1989, p. 129.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 7:55.

- ^ Turner 1982, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Dennis 2007, p. 97.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 9:08.

- ^ a b c d Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 33.

- ^ Conklin 2009, p. 116.

- ^ McPherson, Colvin (September 2, 1939). "Thumbnail Reviews of New Movies". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, MO. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Conklin 2009, p. 170.

- ^ a b c d Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 35.

- ^ Crane 1988, pp. 39–43.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 13:20.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 40.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 40.

- ^ a b c Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 41.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 42.

- ^ Barton 2010, p. 101.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 15:18.

- ^ Valentino 1976, p. 97.

- ^ Holliday, Kate (June 6, 1943). "Glamor Palling on Lana". The Baltimore Sun. Baltimore, Maryland. p. 55 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 49.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 17:10.

- ^ Crane & De La Hoz 2008, pp. 34, 185, 331.

- ^ "Speaking of Pictures ... These Freudian Montage Shots Show Mental State of Jekyll Changing to Hyde". Life. Time, Inc. August 25, 1941. pp. 14–16. ISSN 0024-3019 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 50.

- ^ Schatz 1999, p. 111.

- ^ Time Staff (August 11, 1941). "Review: Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde". Time. Vol. XXXVIII no. 6. Time, Inc. p. 4. ISSN 0040-781X.

- ^ Basinger 1976, pp. 51–53.

- ^ Wayne 2003, p. 173.

- ^ "Gable and Lana Turner Star". San Jose Evening News. San Jose, California. October 17, 1942. p. 4 – via Google News.

- ^ Wayne 2003, p. 174.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 21:05.

- ^ Basinger 1976, p. 54.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 51.

- ^ Agee, James (February 23, 1942). "Cinema: The New Pictures". Time. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- ^ Fischer 1991, pp. 187–189.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 33:33.

- ^ a b c "Lana's Kisses Sell Bonds Without Her Fancy Speech". The Pittsburgh Press. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. June 25, 1942. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Lana's Kisses Really 'Sell'". Eugene Register-Guard. Eugene, Oregon. June 12, 1942. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.Burnt Norton

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 81.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 33:53.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Valentino 1976, p. 28.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 66.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 24:20.

- ^ a b Basinger 1976, pp. 141–142.

- ^ a b Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 69.

- ^ a b Parish 2011, p. 249.

- ^ Turner 1982, pp. 9, 85, 142.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 68.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 70.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 27:00.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 68.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (April 2, 1943). "'Slightly Dangerous,' a Comedy Wherein Lana Turner, Robert Young Appear, at Capitol – 'Saint' Film at the Palace". The New York Times. p. 17. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 77.

- ^ Jordan 2011, p. 232.

- ^ Valentino 1976, p. 133.

- ^ a b c Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 82.

- ^ Valentino 1976, p. 135.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (April 26, 1981). "The Story is the Same But Hollywood Has Changed". The New York Times. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ Brook 2013, p. 120.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 36:18.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 38:45.

- ^ "Movie of the Week: The Postman Always Rings Twice". Life. Time, Inc. 29 April 1946. p. 129. ISSN 0024-3019 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f MacPherson, Virginia (October 12, 1946). "Heavy Drama Her Dish Now, Says Lana". Democrat and Chronicle. Rochester, New York. p. 11 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Manners, Dorothy (August 3, 1946). "Lana Turner To Play Lead In 'Green Dolphin Street". St. Petersburg Times. St. Petersburg, Florida. p. 13 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 39:40.

- ^ Bellows 2006, p. 192.

- ^ a b Wayne 2003, p. 178.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 32:44.

- ^ Brown & Broeske 2004, pp. 199–201.

- ^ "Cass Timberlane". American Film Institute Catalog. Archived from the original on June 18, 2018.

- ^ Manners, Dorothy (August 3, 1946). "News Of The Movies". The San Antonio Light. San Antonio, Texas. p. 6 – via Newspaper Archive.

- ^ McClelland 1992, p. 292.

- ^ Variety Staff (December 31, 1946). "Cass Timberlane". Variety. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Parsons, Louella (August 12, 1947). "Hepburn's Screen Career Unaffected by Frankness". St. Petersburg Times. St. Petersburg, Florida. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Valentino 1976, p. 158.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 42:51.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 44:12.

- ^ Basinger 1976, p. 77.

- ^ Crane 1988, pp. 93–97.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 43:47.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 44:05.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, pp. 111–113.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 44:45.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 112.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 122.

- ^ a b Turner 1982, p. 122.

- ^ Turner 1982, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Thomas, Bob (December 7, 1949). "Lana Turner Says She Is Now the Home-Girl Type". The Post-Register. Idaho Falls, Idaho. p. 9 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 127.

- ^ "Lana Turner leaves Footprints At Grauman's Chinese Theater". Morning Avalanche Newspaper. Lubbock, Texas. May 24, 1950. p. 24.

- ^ Shipman 1970, p. 526.

- ^ Valentino 1976, pp. 171–173.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 124.

- ^ "Pinza Is Tops, Lana Is Dull In 'Mr. Imperium'". St. Petersburg Times. St. Petersburg, Florida. November 6, 1951. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 53:37.

- ^ a b Turner 1982, p. 129.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 56:23.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Turner 1982, pp. 126–134.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, pp. 136–139.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 59:00.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 59:49.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (September 9, 1954). "The Screen in Review; 'Betrayed,' War Story, Opens at the State". The New York Times. p. 36. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 132.

- ^ Parish & Bowers 1973, p. 777.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 155.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 146.

- ^ Variety Staff (December 31, 1954). "The Prodigal". Variety. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 156.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 160.

- ^ Valentino 1976, p. 211.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, pp. 158–159.

- ^ Valentino 1976, p. 207.

- ^ a b Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 161.

- ^ Parish & Bowers 1973, p. 745.

- ^ Wayne 2003, p. 183.

- ^ a b Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 162.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 154.

- ^ Crane 1988, p. 167.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 1:01:15.

- ^ Archer, Greg (November 26, 2008). "The Kid Stays in the Picture". The Advocate. Archived from the original on January 5, 2013.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 175.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 1:08:20.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 1:08:25.

- ^ Variety Staff (December 31, 1957). "Peyton Place". Variety. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- ^ a b Kashner & MacNair 2002, p. 254.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 181.

- ^ Basinger 1976, p. 115.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 158.

- ^ Turner 1982, pp. 200–203.

- ^ Turner 1982, pp. 159–161.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 161.

- ^ Turner 1982, pp. 163–165.

- ^ a b Feldstein 2000, p. 120.

- ^ Turner 1982, pp. 160–191.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 205.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, pp. 177–182.

- ^ Turner 1982, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Fischer 1991, p. 217.

- ^ Turner 1982, pp. 169–172.

- ^ Wayne 2003, p. 185.

- ^ Kohn 2001, p. 388.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 170.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 180.

- ^ Turner 1982, pp. 183–187.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 190.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 186.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 188.

- ^ a b Lewis 2017, p. 94.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 195.

- ^ Feldstein 2000, pp. 120–121.

- ^ a b c d Crane, Cheryl (August 8, 2001). "Lana Turner's Daughter Tells Her Story". CNN (Interview). Interviewed by Larry King. Retrieved May 9, 2018.

- ^ a b c Turner 1982, p. 203.

- ^ Feldstein 2000, p. 122.

- ^ Valentino 1976, p. 221.

- ^ Smith, Doug (August 15, 2015). "In a 1958 inquest, killing of Lana Turner's boyfriend was detailed". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ^ a b Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 233.

- ^ a b c Erickson 2017, p. 119.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 1:19:15.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 215.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 217.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 1:20:05.

- ^ Langer 2001, event occurs at 1:20:09.

- ^ a b c Thomas, Bob (May 8, 1957). "Lana Turner Says She's Had It; Won't Marry Again". Port Angeles Evening News. Port Angeles, Washington: Associated Press. p. 12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Kashner & MacNair 2002, p. 267.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 219.

- ^ Variety Staff (December 31, 1959). "Imitation of Life". Variety. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 208.

- ^ Kashner & MacNair 2002, p. 257.

- ^ Turner 1982, pp. 215–221.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 221.

- ^ "Lana Turner Gives Up Movie Role". La Grande Observer. La Grande, Oregon. March 5, 1959. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Turner 1982, pp. 263–265.

- ^ Thomas 1997, p. 191.

- ^ Wayne 2003, p. 187.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 223.

- ^ Duncan, Ray (July 3, 1960). "Lana Turner Suspense Film Strains Credibility". Independent Star-News. Pasadena, California. p. 39 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 210.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 217.

- ^ Wayne 2003, p. 188.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 236.

- ^ Valentino 1976, p. 234.

- ^ Slide 1998, p. 101.

- ^ Valentino 1976, p. 240.

- ^ "Lana Turner, Fifth Husband Separate; No Divorce Yet". Deseret News and Telegram. Salt Lake City, Utah. September 23, 1962. p. C7 – via Google News.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 223.

- ^ Turner 1982, pp. 226.

- ^ Valentino 1976, pp. 247–249.

- ^ Terry, Clifford (March 14, 1966). "Lana Makes Melodrama 'Madame X' Credible". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois. p. 59 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Monahan, Kaspar (March 31, 1966). "Lana Turner at Her Peak in 'Madame X'". Pittsburgh Press. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. p. 32 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Valentino 1976, p. 251.

- ^ Morella & Epstein 1971, p. 260.

- ^ Kong, William T. (September 13, 1969). "Lana Turner Big Zero in 'Big Cube'". Des Moines Tribune. Des Moines, Iowa. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Milestones: April 11, 1969". Time. April 11, 1969. Archived from the original on April 6, 2008. Retrieved June 25, 2017.

- ^ Turner 1982, p. 232.

- ^ Turner 1982, pp. 286–287.

- ^ Turner 1982, pp. 232–233.

- ^ a b Turner 1982, p. 233.

- ^ "All-Star Line-up for 'Love'". Los Angeles Times. December 5, 1968. p. 26 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Robbins 2008, p. 222.

- ^ a b Jordan 2009, p. 227.

- ^ Jones, J. Harry (August 5, 2006). "The amazing Dr. Dante has seen it all". The San Diego Union Tribune. San Diego, California. Archived from the original on July 4, 2014.

- ^ Chambers, Andrea; Adelson, Suzanne (November 8, 1982). "Lana Turner". People. 18 (19). Archived from the original on December 3, 2013.

- ^ a b Thomas, Bob (July 1, 1995). "'Peyton Place' Star Lana Turner Dies". The Times and Democrat. Orangeburg, South Carolina: Associated Press. p. 12 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Valentino 1976, pp. 255–257.

- ^ Variety Staff (December 31, 1973). "Persecution". Variety. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- ^ Quinn, Sally (April 22, 1975). "Camp followers". The Guardian. London. p. 15 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Valentino 1976, p. 288.

- ^ Van Gelder, Lawrence (March 24, 1977). "Film: Dilemma of Incest". The New York Times. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ a b c Turner 1982, p. 245.

- ^ Collins, William B. (July 21, 1971). "'40 Carats' Shines With Lana's Glamor". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. p. 18 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Valentino 1976, p. 284.

- ^ Shearer, Lloyd (August 28, 1977). "Lana's Lectures". San Bernardino Sun. San Bernardino, California. p. 113 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

- ^ Gussow, Mel (July 22, 1977). "Along the Straw-Hat Trail". The New York Times. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ Matas, Elaine. "'Sweater Girl' of the '40s brilliant in 'Bell, Book and Candle' at Lakewood". Standard-Speaker. Hazleton, Pennsylvania. p. 26 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Christiansen, Richard (November 3, 1978). "Lana Turner in 'Divorce' Entertains Just Being Lana". Chicago Tribune. p. 39 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Lana Turner". Detroit Free Press. Names & Faces. Detroit, Michigan. October 29, 1978. p. 45 – via Newspapers.com.